Abstract

Introduction

Third molar surgery (TMS) became a routine, safe office procedure with generally predictable outcomes and relative low cost. It affects quality of life (QOL) of patients by causing considerable pain, swelling and trismus; by changing what people eat, their speech in the first few days after surgery. The purpose of the present study was to improve QOL of patient after lower TMS by injecting single dose 8 mg submucosal dexamethasone.

Materials and Methods

Forty healthy adult subjects of either gender underwent surgical removal of the lower impacted third molar under local anaesthesia and after being randomly assigned to receive either 8 mg dexamethasone submucosal injection or normal saline injection in proximity to surgical site.

Statistical Analysis Used

Chi-square test, Mann–Whitney U test (Z), t student and unpaired t test, and Fisher extract test were used for calculation of data.

Results

Facial swelling, trismus showed significant reduction immediate postoperative day in dexamethasone groups. Patient perception postoperative pain on VAS score was not significant. PoSSe statistics, only three out of seven subscales showed a statistically significant difference between groups viz., Eating subscale, Appearance subscale, Sickness subscale but over all improvement in QOL was observed.

Conclusions

Submucosal dexamethasone effectively reduces postoperative sequelae and improves postoperative QOL after TMS.

Keywords: Quality of life, Submucosal Injection of dexamethasone, Third Molar, Third Molar Surgery, Corticosteroid in oral surgery, Post operative sequelae

Introduction

Since 1960, “quality of life (QOL)” has been discussed in various settings (medical, social sciences, philosophy, etc.). Different settings adopt the term QOL for different purposes. Each of them uses different kinds of assessment [1]. The concept of QOL related to health status has attracted increasing interest among clinicians over the last three decades [2]. Clinicians have accepted that patient centre outcome scale (subjective) is more effective than objective testing or surgeon rated score [3]. There is no definition of QOL accepted universally. However, QOL is defined as patient’s perception of his position in life which is the effect of disease and treatment; affected in a complex way by the person’s physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs and relationship to salient features of the environment [4]. QOL has become widely known and used by many clinical trials due to multidimensional (bio psychosocial) concepts [5]. In the past decade, there were important methodological developments in instruments used to measure it— fundamentally based on open and close ended questionnaires [6].

TMS, one of the most common oral surgical procedures can be performed in outpatient setting. Nearly, all patients report pain, oedema, erythematic, warmth, and loss of function for the first few days after surgery; affects the post operative QOL. Moreover, it increases the post operative phone call to the clinician [7].

To minimize these, several medications or techniques such as atraumatic surgical manipulation and low-laser therapy have been proposed in literature. Various types and forms of corticosteroid are widely accepted by the oral and maxillofacial community [8]. However, method of usage of corticosteroid in literature has varied; most effective agents, site, dose and route have yet to be defined with respect to TMS [9]. Despite the frequent clinical use of dexamethasone, there are a few reports of corticosteroid administered in proximity to surgical site which have shown positive response after TMS [10–16]. Even though, QOL measures after administration of preoperative single dose submucosal dexamethasone remains poorly investigated.

In an excellent review article by Gersema and Baker [17] the authors suggested that the effect of dexamethasone is dose dependent and administration of <4 mg is not beneficial. The aim of the present study was to determine the efficacy of single dose 2 ml/8 mg submucosal dexamethasone injection in the buccal vestibule in proximity to the surgical site. A study hypothesis was formed stating that “single dose 8 mg submucosal dexamethasone affect immediate postoperative QOL measures after third molar surgery.”

Materials and Methods

This prospective, randomized, control trial was carried out from March 2009 to October 2009 after obtaining approval from the institutional ethical committee. The inclusion criteria were subjects between 20 and 41 years of age who were in good general physical health with no clinically significant and relevant medical history (ASA level I and II). Subjects having at least one partially or fully bony impacted mandibular third molar (Pell and Gregory class II or III 3rd molar impaction) and who could understand and were willing to take part in the study and likely to comply with all study procedure were included in this study.

The exclusion criteria were the subjects who were on antibiotics and or anti-inflammatory drugs within 2 weeks of the study entry, pregnant or lactating females and subjects with any active medical illness. Subjects were also excluded in whom the surgery lasted for more than 1 h and for whom the use of non-trial drugs were prescribed during study period.

Preoperative Assessment

The base line facial contour and inter incisor opening (IIO) measurement was done by a 3–0 silk suture using the method described by Deo and Shetty [15]. The study subjects were randomly assigned into two groups: Dexamethasone group (DXG) and Control group (CTG). For randomization, a random-number table was used to generate a block randomization schedule chart, specifying the group to which each subject would be assigned upon first come first basis. Also, blinding this clinical trial was done by confidential supporting staff as described by Deo and Shetty [15]. Neither surgeon nor subjects were known about the trial preoperative drugs (2 ml dexamethasone or 2 ml normal saline in identical syringe).

Surgical Technique

The subject was prepared for TMS; 2 ml of lignocaine 2 % with epinephrine 1:2,00,000 (Xylocaine 2 %, Astrazeneca, India) was used as the anaesthetic agent to block the inferior alveolar, lingual and long buccal nerve. After securing under profound local anaesthesia, subjects either received 2 ml of 4 mg/ml dexamethasone (Inj Dexona, Zydus Aliadac, India) or 2 ml normal saline (Zuche, New Delhi, India) as per randomization schedules chart; injected submucosally into the buccal in proximity to the surgical site. The surgical procedure was standardized by a 3-cornered mucoperiosteal flap. Bone was removed by a buccal guttering and distal bone cutting with a fissure bur on a straight handpiece under continuous irrigation with sterile normal saline. The crown or roots were sectioned when necessary. After tooth extraction, the socket was inspected, filed and irrigated with normal saline. After achieving haemostasis, the flap was approximated and primary closure was obtained using 3–0 silk suture. Pressure pack was given intra-orally. The duration of the operation was recorded as the period between the incision and the last suture placed. Detail of each procedure was recorded. All the subjects were operated by the same operator and under similar conditions to minimize operator variability. Post-operative instructions were given to subjects, including an ice pack for 20 min and a pressure pack for 30 min over the surgical site to achieve haemostasis. All the subjects were prescribed Amoxicillin 500 mg (Cap Aristomox500, Aristo, India) per oral three times a day for 5 days and Ibuprofen 400 mg (Fc-tab Brufen400, Abbott, India) per oral as required as “rescue” analgesia. The subjects were asked to take the first analgesic post-operatively as soon as the pain reached moderate level and were asked to record the time. The subjects were instructed not to take any other analgesic drugs. They were asked to report to the outpatient setting on the 2nd and 7th post-operative days.

Postoperative Assessment

All the subjects were given questionnaires 10 cm visual analogue scale (VAS) and instructed about the rating. Postoperative pain was rated daily for 7 days using a 10-point numerical rating scale and 10 cm VAS anchored by the verbal description “no pain” (0) and “very severe pain” (9). They were asked to enter their pain level, the time at which the analgesic was taken, and the number of tablets taken until the end of the first post-operative week. The maximum inter-incisor distance and facial contours were measured on these appointments by the same examiner who had assessed them pre-operatively. The technique and reference points used for these measurements were the same as those based on the pre-operative assessment. The evaluation of trismus and facial oedema was recorded as the difference between pre-operative (baseline) and post-operative values.

On the seventh day postoperatively, subjects were requested to complete the PoSSe scale. This questionnaire was designed by Ruta et al. [18] to assess the subject’s perception of adverse effects on seven subscales: eating, speech, sensation, appearance, pain, sickness, and interference with daily activities. A score was assigned to the possible responses to each forced question to assess the QOL after TMS. These scores represent percentages in the group choosing response category for each question.

Data Analysis

All the demographic details, base line data and postoperative data were recorded in the case report form over the course of the study. All the data were entered into the spreadsheet (excel, Microsoft) and Chi-square test, Mann–Whitney U test, t student’s paired and unpaired t test, and Fisher exact test were used for analysis of the data.

Results

Sample Characterization

Forty subjects aged between 20 and 41 years were selected on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Twenty-four subjects were enrolled in the DXG and 16 subjects in the CTG. Ten subjects were excluded from the study. Three had an operating time exceeding an hour, two had been taking analgesics other than prescribed, three were lost for follow-up and two subjects did not complete the questionnaire properly. Data from 30 subjects were included in the study and analysed.

Objective Data

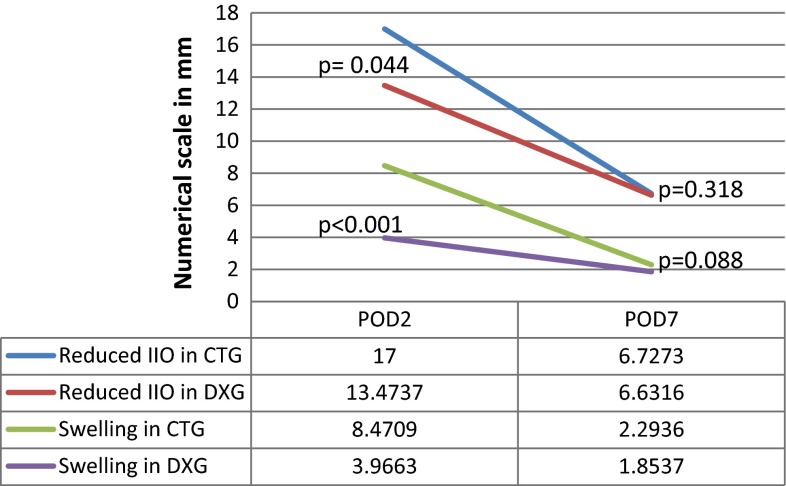

On the second postoperative day (POD), DXG had statistically significant reduction in the facial swelling (Z = 3.961, P < 0.001) and trismus (Z = 2.016, P = 0.044). But on the seventh post-operative day, both DXG and CTG had statistically similar facial swelling (Z = 1.704, P = 0.088) and trismus (Z = 0.999, P = 0.318) Fig. 1. Also groups statistics showed no significant difference (P = 0.124) in the total number of analgesics received after TMS; DXG (9.21 ± 2.64) had taken almost the same number as that of the CTG (10.82 ± 2.75).

Fig. 1.

Objective data in 2nd and 7th PODs; Significant recovery of Trismus and swelling was observed in DXG on 2nd POD which gradually resolved to baseline on 7th POD

Patient’s Perception

Patient’s perception about postoperative pain on VAS score showed progressive reduction in pain intensity from the first to the seventh post-operative day in both the groups (Fig. 2). The PoSSe statistics, only three out of seven subscales showed a statistically significant difference between groups; Eating subscale, Appearance subscale, Sickness subscale.

Fig. 2.

VAS score reported by subjects from 1st to 7th POD

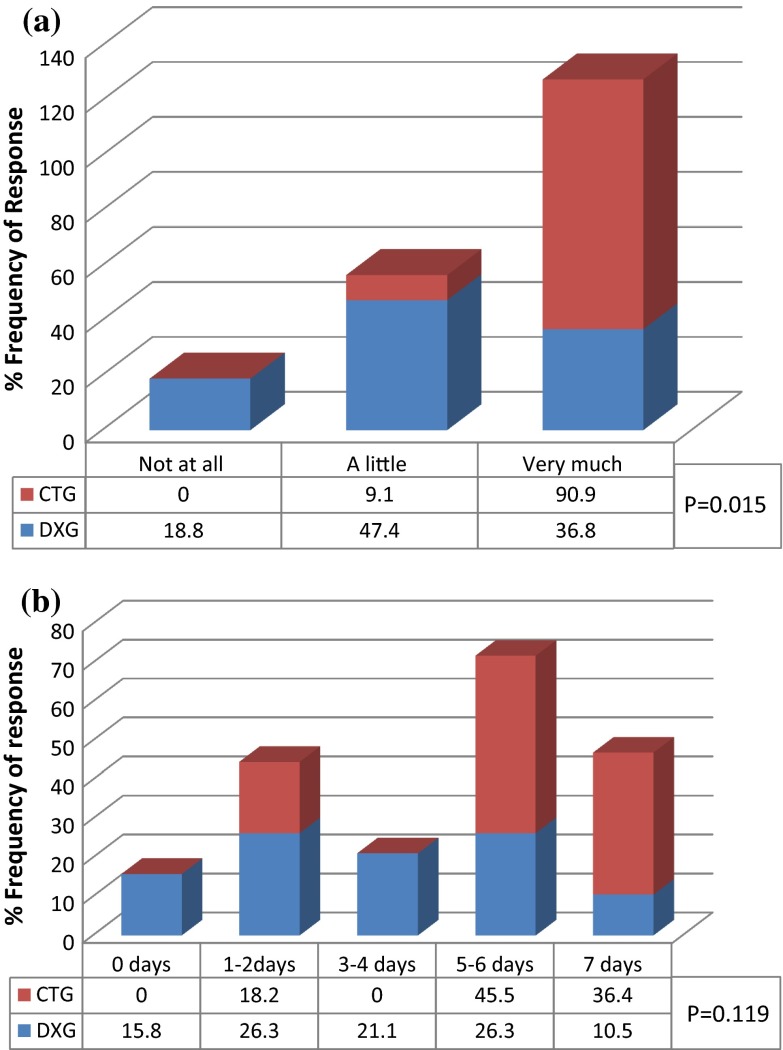

In this study, out of two forced questions of “Eating subscale”, only response from enjoyment of food had statistically significant differences (P = 0.015) whereas result did not show significant difference (P = 0.119) in unable to open mouth. A very large number (91 %) of CTG rated the TMS affected on enjoyment of food as “very much”, whereas only 37 % of the DXG were similarly affected. Nearly 50 % of DXG were “little affected” in enjoyment of food, whereas not even a single CTG enjoyed food in the post-operative period (Fig. 3a). About 82 % of CTG had limited mouth opening for more than 5 days whereas only 37 % of DXG had limited mouth opening for more than 5 days. Not even a single CTG had normal mouth opening whereas 16 % of DXG had normal mouth opening postoperatively (Fig. 3b). The interesting finding of this study is that subjects who had higher inability of mouth opening also consumed higher number of analgesic.

Fig. 3.

Eating subscale. a Percent subjects responded, operation affect on enjoyment of food in 1st postoperative week. b Percent of subjects were unable to open mouth normally in 1st postoperative week because of operation

In response to the question of speech affected 73.7 % of DXG and 81.8 % of CTG rated ‘not at all’ to ‘slight’ difficulty in speech after TMS (Fig. 4a). Voice affected in DXG usually lasted not more than 3–4 days whereas in CTG it might last upto 7 days (Fig. 4b). Both questions of “Speech subscale” did not have statistically significant difference while comparing between the groups. With respect to subjects perceiving “none at all” sensation; 73.7 % of DXG felt numbness and tingling whereas only CTG felt 45.5 and 54.5 % numbness and tingling of lip and tongue, respectively. Some of subjects 26.3 % DXG and 54.5 and 45.5 % CTG reported the same “1–2 days” over postoperative week. None of the subjects from both groups reported more than 2 days numbness and tingling of lip and tongue (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Speech subscale. a Percent of subjects who reported many days in a 1st postoperative week voice affected because of the operation. b On the worst day, percent of subjects were speech affected by the operation

Fig. 5.

Sensation subscale. Percent of subjects who felt tingling and numbness of lips or tongue because of operation within a week

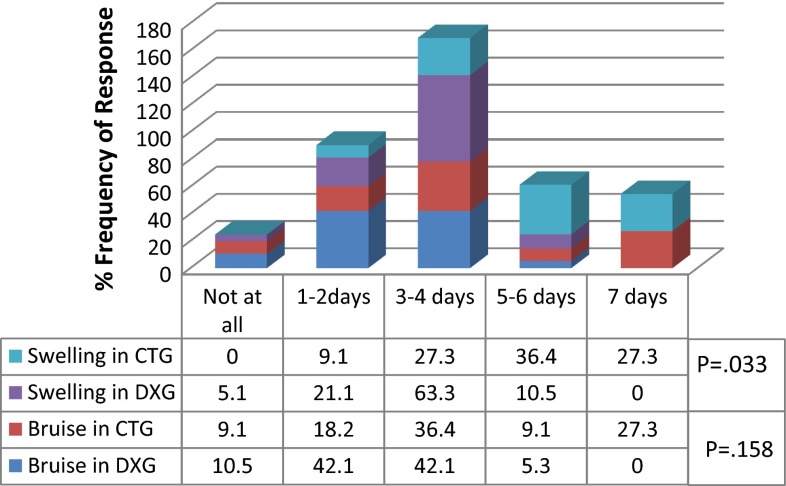

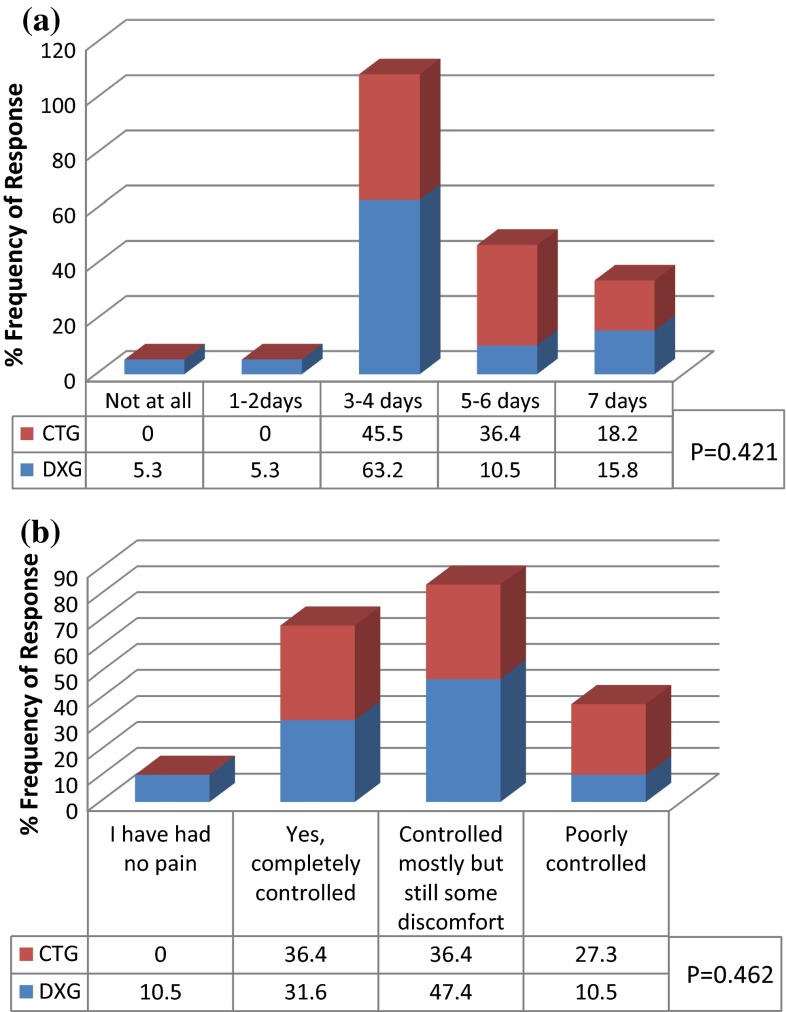

On postoperative week, 94.7 % of DXG and 63.7 % of CTG experienced erythema/bruise of the ipsilateral side of the face in <4 days. In addition, 89.5 % of DXG but only 36.4 % of CTG had swollen face in <4 days. None of the subjects of DXG had swollen face up to 7 days whereas 27.3 % CTG had swollen face up to 7 days (Fig. 6). This was statistically significant (P = 0.033). Both groups (DXG 63.2 % and CTG 45.5 %) experienced pain for 3–4 days. 10.6 % of DXG but none in CTG experienced pain for <2 days (Fig. 7a). Pain was well controlled by analgesics in both groups. As many as 90 % of DXG whereas only 73 % of CTG responded; they were “absolutely fine” in terms of freedom from pain postoperatively (Fig. 7b). This data was not statistically significant between the groups.

Fig. 6.

Appearance subscale. Percent of subjects who reported many days bruise and swollen face and/or neck because of the operation

Fig. 7.

Pain subscale. a Percent of subjects who experienced pain within a week after the operation. b Percent of subjects who responded pain controlled by pain killers up to 1st post-operative week

94.7 % of DXG felt nausea and vomiting “not at all” whereas only 36.4 % CTG experienced the same. 5.3 % DXG and 54.5 % of CTG experienced it for 1–2 days (Fig. 8a). While comparing between groups, this data was statistically highly significant (P = 0.002). No subjects responded more than 3–4 days. Even, on the worst day of surgery, DXG responded “not at all” about 90 % whereas 54.6 % of CTG experienced more than 1 time nausea and vomiting. This was again statistically significant (P = 0.22) (Fig. 8b).

Fig. 8.

Sickness subscale. a Percent of subjects who reported vomiting or feeling nauseated in 1st postoperative week. b On the worst day of the last week, percent of subjects felt many times vomiting or nausea

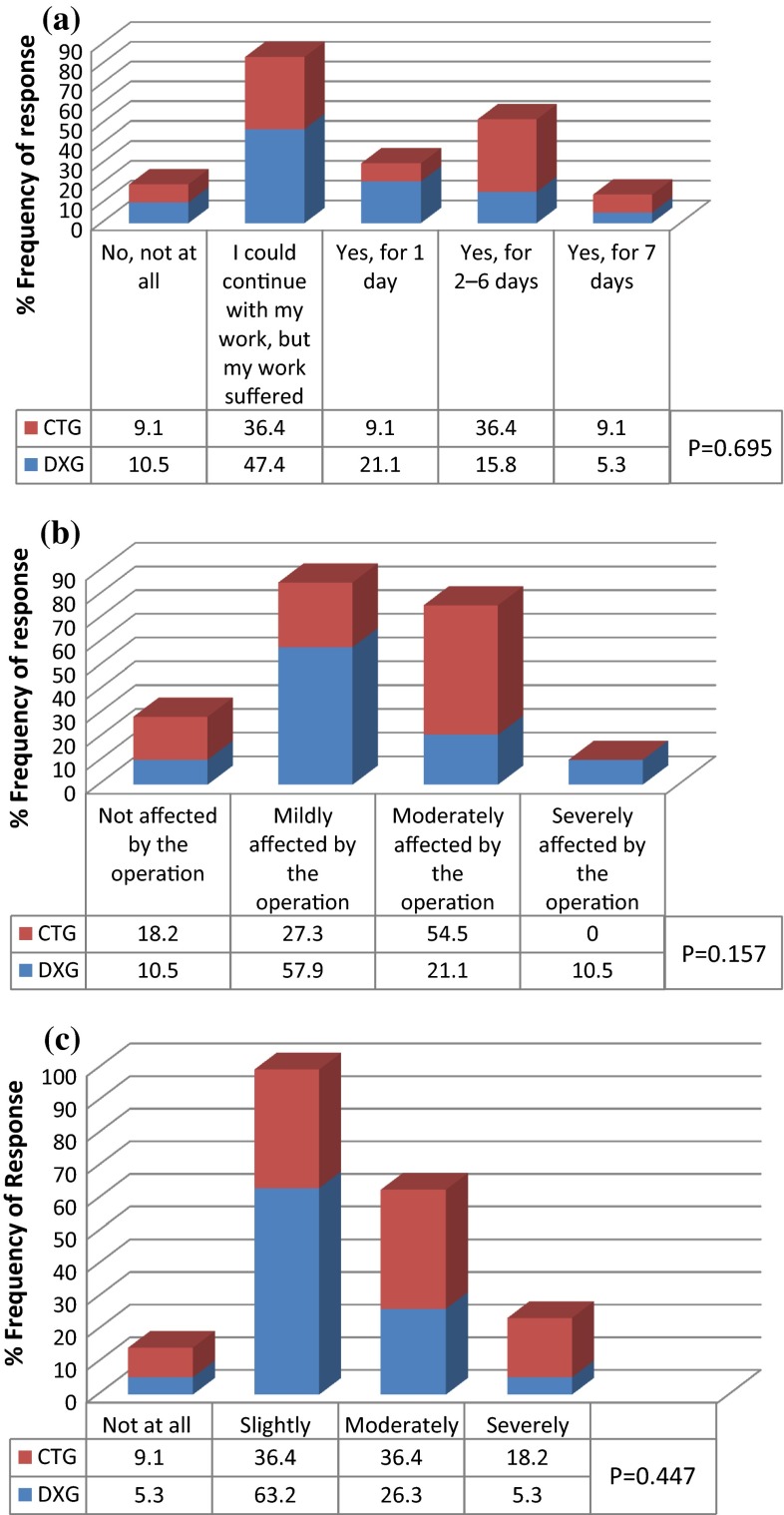

58 % of DXG and 45.5 % of CTG had continued with daily work. However, 21 % DXG required 1 day off work whereas 9 % CTG required 1 day off work. Rest 21 % DXG and 45.5 % of CTG took more than 2 days off work (Fig. 9a). Leisure activities were mildly affected in 58 % of DXG whereas only 27.3 % of the CTG subjects said they were “mildly affected” by the operation. 54.5 % of CTG were moderately affected, whereas only 21.1 % of subjects in DXG reported the same degree of interference in leisure activity (Fig. 9b). 63 % of DXG were slightly affected by postoperative pain whereas only 36.4 % of CTG reported slight degree of pain; only 21.6 % of DXG experienced moderate to severe pain where as 54.6 % CTG reported moderate to severe pain (Fig. 9c). Interference in daily activities subscale was not statistically significant between the groups.

Fig. 9.

Interference with daily activities subscale. a Percent of subjects could not carry out work/housework and other daily activities in 1st postoperative week. b Percent of subjects who reported with affect of leisure activities including sports, hobbies and social life in 1st postoperative week. c Percent of subjects who reported affected your life due to the pain in 1st postoperative week

Discussion

TMS is the most debatable issue for clinicians due to its high operative cost and associated morbidity. Past studies showed that a deterioration in oral health related QOL, occurred in the short term (immediate postoperative) after TMS [19–23]. To deliver the best practices, many guidelines have been proposed for extraction of wisdom teeth [24, 25]. However, this guideline would not be applicable all over the world specially in a poor country like Nepal where surgical cost is very low and also, patients live with various untreated systemic diseases. The people of this subcontinent lack awareness about preventive measures as well as the early treatment of symptomatic diseases. Here, patients report to clinician at advanced stage of disease i.e. severe pain, potential space infection or cyst. At this stage, overall treatment cost as well as the morbidity might increase significantly. Even though there was evidence that active surveillance of third molar might not avoid aggressive treatment in the future; this should not be patients’ preferred management strategy [25]. Hence, clinicians of this subcontinent should consider TMS as a management strategy. Recently, TMS has became a routine, a safe office procedure with generally predictable outcomes and relative low cost due to the development of high speed cutting instruments, panoramic radiograph, improved local anaesthesia and advanced surgical techniques. Moreover, the previous studies which investigated efficacy and effectiveness of preoperative submucosal dexamethasone, gave encouraging results compared with controls in reducing the post-operative sequelae of TMS [13–16]. Due to this the clinician feels easy to inform their patients about TMS.

Many reports support the use of local application of dexamethasone in the setting of TMS [11–16]. But those studies demonstrated conflicting results because of the limited number of subjects, different route and dose of corticosteroid administered, use of different surgical techniques and lack of standardized anaesthetic technique (Local or General). In this study, entire subjects were operated by single surgeon under Local anaesthesia. During TMS, the underlying muscle tissue and surrounding tissues were damaged mechanically or thermally, or both which was directly related to surgeon’s ability and technique. As a result, acute inflammatory response was elicited in the surrounding tissues as well as disruption of the oral mucosa causing spasm of masticatory and pharyngeal muscles and irritation of nerve endings. These events result in imbalance in the delicate mechanism of swallowing, incoordination, dysphagia, trismus, swelling and pain and affects the postoperative QOL. Usually, such phenomenon would cause stress to clinician while counselling and taking informed consent as well as increase pre or postsurgical anxiety and traumatic stress sequelae in the patient [26].

The mechanism of action of corticosteroids is quite complex; there is generally a lag of several hours before their effects are manifested (dexamethasone takes 1–2 h to act). In a typical practice setting, administering corticosteroids 1–4 h before surgery is usually not convenient. Therefore, this study intended to produce rapid action before the inflammatory mediator release. But reviewing various previous studies, the reason of rapid action that occurs in a few minutes as in this study could be due to nongenomic path of action by administering submucosal (tropical) injection of dexamethasone [10–16]. This pathway does not require de novo protein synthesis and acts by modulating the level of activation and responsiveness of target cells, such as monocytes, T cells, and platelets and also leads to peripheral vasoconstriction which further increases local drug concentrations [27].

Ample studies have shown a significant recovery of the post-operative swelling and trismus in patients who were administered a single dose submucosal dexamethasone in proximity to surgical site preoperatively during TMS [13–15]. The findings of this study are quite similar to those previous studies; facial swelling and trismus were maximum in 2nd POD whereas it was least (baseline) in 7th POD. Figure 2 showed progressive reduction of postoperative swelling and trismus in both groups. Surprisingly, Graziani et al. [10] found significant reduction on 7th POD which itself is contradicting. Usually the swelling of the face resolves after a week of surgery. The long-term effect of dexamethasone is not justifiable because the biological half-life of dexamethasone is 36–48 h and hence its duration of action will be only up to the 2nd POD but not up to the 7th or more PODs [15].

Many investigators have suggested submucosal administration of dexamethasone to improve immediate postoperative QOL after TMS [13–15]. In this study, out of seven PoSSe subscales, three subscales had statistically significant difference between two groups; “Eating”, “appearance” and “sickness” subscales were significant whereas “speech”, “sensation”, “pain”, and “interference with daily activities” subscales were improved in DXG as compare to CTG. The results from the present study disagree with those from Grossi et al. [13] who found no significant effect on the QOL domains, other than the “appearance” subscale as well as from Majid [16] who reported statistically significant differences in all subscales of QOL (except for the speech subscale) during the postoperative period. Majid [16] measured QOL in five subscales instead of seven PoSSe subscales; “social”, “eating” “sleep”, and “appearance”. The limitation of both studies was that, neither the patients nor the surgeons was blinded to the use of dexamethasone.

Surprisingly, Majid [16] had no comment on “speech” subscale although there was a significant recovery in mouth opening after TMS. This contradicted his own result. Social, Eating, Speech, Sleep, Appearance subscales had significant positive correlations with swelling, trismus, and pain. In fact, speech and oral function of individual is directly related to mouth opening. Previous studies reported change in eating habit and speech respectively many days after surgery but dexamethasone showed impressive improvement [15, 16, 28].

Pain also influences the effect of TMS on QOL. Findings of this study is quite similar to the previous studies using submucosal route. VAS Score and total number of analgesics used was not statistically different between the groups [12–15]. However, Majid [16] found that the significant analgesic effect could be a different mechanism which was not clearly explained. Although, the design of this study was very similar to Majid’s [16] study; he did not measure the time at which first analgesic was consumed in both groups. VAS score and number of analgesic tablets are good parameters to assess the analgesia, but these are not reliable to compare between the groups over time. As the effect of dexamethasone on pain diminished, DXG behave as CTG hence VAS and total number of analgesic was statistically similar between the groups in this study. Furthermore, pain perception and tolerance varies among individuals therefore patients might have taken a pain medication although the pain was not severe. The significant analgesic effect may be justifiable only up to 3–6 h postoperatively. However, including this study, previous studies have used VAS and the total number of analgesics to compare between groups daily for a week [12–15]. A patient’s decision to take a pain medication seems to reflect a level of dissatisfaction with his pain at the moment. Smartly, Majid [16] recorded VAS 6 h postoperatively. Hence a significant analgesic effect was elicited in preoperative submucosal dexamethasone injection. Similarly, this study measured the exact time at which 1st analgesic was taken immediate postoperatively which was found to be highly significant. Further, our subjective data also support the analgesic action of dexamethasone in submucosal route; postoperative pain lasted 3–4 days and was well controlled by the analgesic prescribed.

Usually postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) are unwanted side effects of medications administered for anaesthesia, antibiotics and pain control. PONV can occur after TMS under local anaesthesia due to result of swallowed blood, discomfort, drugs (analgesic, antibiotics). There are not many data available on the incidence of PONV which is commonly reported in different ambulatory procedures under general anaesthesia (18–58 %) [19, 28]. However, the recent studies did not find any differences in incidence of PONV in setting of TMS under local and general anaesthesia. The incidence of PONV found by Sato et al. [22] was 15.7 % under local anaesthesia whereas it was 20 % by Tiwana et al. [28] under general anaesthesia in their control group after TMS. Many of the studies successfully demonstrated reduction of incidence of PONV by administering dexamethasone [28–31]. Data from the present study is supported by the study by Tiwana et al.; it significantly decreased PONV after TMS under local anaesthesia by administrating single-dose of submucosal (8 mg) dexamethasone preoperatively than control group [28]. Additionally, significantly fewer patients felt PONV in first 24 h even on the worst day after TMS. Probable mechanism is that dexamethasone may exert an antiemetic action via prostaglandin antagonism, serotonin inhibition in the gut, and release of endorphins.

The previous studies found that very high number (four out of every five, 80 %) of patients required some time off work for some days [22–25]. The reason for disruption of job was mainly linked with facial appearance, inability to open mouth and speech, pain, sickness, dysphagia, sleeping problems which dramatically improved after injecting submucosal dexamethasone. Correlation between objective and subjective data performed in various studies seem true in this study. It decreased swelling associated with the appearance and interference with daily activities subscales. The patient’s satisfaction and comfort was directly related to decrease in postoperative trismus, pain, sickness subscales [13, 16, 19, 28].

In conclusion, submucosal dexamethasone injection can be a smart choice for clinicians in TMS under local anaesthesia as it effectively reduces postoperative sequelae and improves postoperative QOL. Submucosal dexamethasone injection in anaesthetized region offers the advantage of painless injection. It is not dependent on patient compliance, concentrating the drug near the surgical area without noticeable systemic side effects. This route might be convenient for the surgeon as well as patient and offers a low-cost solution.

Acknowledgments

My heartfull thanks to Mrs Rachana Deo for her technical support.

Abbreviations

- ASA

American society of anesthesiologists (physical status classification system)

- CTG

Control group

- DXG

Dexamethasone group

- Fig

Figure

- IIO

Inter incisor opening

- POD

Postoperative day

- PoSSe

Postoperative symptoms and severity scale

- PONV

Postoperative nausea and vomiting

- QOL

Quality of life

- TMS

Third molar surgery

- VAS

Visual analog scale

- VAS1-7

Total VAS score in a week

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Pais-Ribeiro JL. Quality of life is a primary end-point in clinical settings. Clin Nutr. 2004;23(1):121–130. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(03)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGrath C, Comfort MB, Lo EC, Luo Y. Patient-centred outcome measures in oral surgery: validity and sensitivity. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41(1):43–47. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(02)00289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden GR, Bissias E, Ruta DA, Ogston S. Quality of life following third molar removal: a patient versus professional perspective. Br Dent J. 1998;185(8):407–410. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doward LC, McKenna SP. Defining patient-reported outcomes. Value Health. 2004;7(Suppl 1):S4–S8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.7s102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan RM. The significance of quality of life in health care. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(Suppl 1):3–16. doi: 10.1023/a:1023547632545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swaine-Verdier A, Doward LC, Hagell P, Thorsen H, McKenna SP. Adapting quality of life instruments. Value Health. 2004;7(Suppl 1):S27–S30. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.7s107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colorado-Bonnin M, Valmaseda-Castellón E, Berini-Aytés L, Gay-Escoda C. Quality of life following lower third molar removal. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:343–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markiewicz MR, Brady MF, Ding EL, Dodson TB. Corticosteroids reduce postoperative morbidity after third molar surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66(9):1881–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antunes AA, Avelar RL, MartinsNeto EC, Frota R, Dias E. Effect of two routes of administration of dexamethasone on pain, edema, and trismus in impacted lower third molar surgery. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;15(4):217–223. doi: 10.1007/s10006-011-0290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graziani F, D’Aiuto F, Arduino PG, Tonelli M, Gabriele M. Perioperative dexamethasone reduces post-surgical sequelae of wisdom tooth removal. A split-mouth randomized double-masked clinical trial. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35(3):241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nobuhara WK, Carnes DL, Gilles JA. Anti-inflammatory effects of dexamethasone on periapical tissues following endodontic overinstrumentation. J Endod. 1993;19(10):501–507. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehrvarzfar P, Shababi B, Sayyad R, Fallahdoost A, Kheradpir K. Effect of supraperiosteal injection of dexamethasone on postoperative pain. Aust Endod J. 2008;34(1):25–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2007.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grossi GB, Maiorana C, Garramone RA, Borgonovo A, Beretta M, Farronato D, Santoro F. Effect of submucosal injection of dexamethasone on postoperative discomfort after third molar surgery: a prospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65(11):2218–2226. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majid OW, Mahmood WK. Effect of submucosal and intramuscular dexamethasone on postoperative sequelae after third molar surgery: comparative study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;49(8):647–652. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deo SP, Shetty P. Effect of submucosal injection of dexamethasone on post-operative sequelae of third molar surgery. J Nepal Med Assoc. 2011;51(182):72–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Majid OW. Submucosal dexamethasone injection improves quality of life measures after third molar surgery: a comparative study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(9):2289–2297. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gersema L, Baker K. Use of corticosteroids in oral surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:270–277. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(92)90325-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruta DA, Bissias E, Ogston S, Ogden GR. Assessing health outcomes after extraction of third molars: the postoperative symptom severity (PoSSe) scale. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;38(5):480–487. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2000.0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White RP, Jr, Shugars DA, Shafer DM, Laskin DM, Buckley MJ, Phillips C. Recovery after third molar surgery: clinical and health-related quality of life outcomes. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(5):535–544. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips C, Gelesko S, Proffit WR, White RP., Jr Recovery after third-molar surgery: the effects of age and sex. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;138(6):700.e1–700.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGrath C, Comfort MB, Lo EC, Luo Y. Can third molar surgery improve quality of life? A 6-month cohort study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(7):759–763. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato FR, Asprino L, de Araujo DE, de Moraes M. Short-term outcome of postoperative patient recovery perception after surgical removal of third molar. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(5):1083–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shugars DA, Gentile MA, Ahmad N, Stavropoulos MF, Slade GD, Phillips C, Conrad SM, Fleuchaus PT, White RP., Jr Assessment of oral health-related quality of life before and after third molar surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(12):1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheldon TA, Cullum N, Dawson D, Lankshear A, Lowson K, Watt I, West P, Wright D, Wright J. What’s the evidence that NICE guidance has been implemented? Results from a national evaluation using time series analysis, audit of patients’ notes, and interviews. BMJ. 2004;329(7473):999. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7473.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dodson TB. Surveillance as a management strategy for retained third molars: is it desirable? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(9 Suppl 1):S20–S24. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evan AW, Leeson RM, Petrie A. Correlation between patients centered outcome score and surgical skill in oral surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43(6):505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uva L, Migual D, Pinheiro C, Antunes J, Cruz D, Ferreira J, Filipe P. Mechanisms of action of topical corticosteroids in psoriasis. Int J Endocrinol. 2012;2012:561018. doi: 10.1155/2012/561018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tiwana PS, Foy SP, Shugars DA, Marciani RD, Conrad SM, Phillips C, White RP. The impact of intravenous corticosteroids with third molar surgery in patients at high risk for delayed health-related quality of life and clinical recovery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63(1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Negreiros RM, Biazevic MG, Jorge WA, Michel-Crosato E. Relationship between oral health-related quality of life and the position of the lower third molar: postoperative follow-up. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(4):779–786. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bradshaw S, Faulk J, Blackey GH, Philips C, Phero JA, White RP., Jr Quality of life outcome after third molar removal in subjects with minor symptoms of pericoronitis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(11):2494–2500. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaan MN, Odabasi O, Gezer E, Daldal A. The effect of preoperative dexamethasone on early oral intake, vomiting and pain after tonsillectomy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70(1):73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]