Abstract

Behavioral economic demand curve indices of alcohol consumption reflect decisions to consume alcohol at varying costs. Although these indices predict alcohol-related problems beyond established predictors, little is known about the determinants of elevated demand. Two cognitive constructs that may underlie alcohol demand are alcohol-approach inclinations and drinking identity. The aim of this study was to evaluate implicit and explicit measures of these constructs as predictors of alcohol demand curve indices. College student drinkers (N = 223, 59% female) completed implicit and explicit measures of drinking identity and alcohol-approach inclinations at three timepoints separated by three-month intervals, and completed the Alcohol Purchase Task to assess demand at Time 3. Given no change in our alcohol-approach inclinations and drinking identity measures over time, random intercept-only models were used to predict two demand indices: Amplitude, which represents maximum hypothetical alcohol consumption and expenditures, and Persistence, which represents sensitivity to increasing prices. When modeled separately, implicit and explicit measures of drinking identity and alcohol-approach inclinations positively predicted demand indices. When implicit and explicit measures were included in the same model, both measures of drinking identity predicted Amplitude, but only explicit drinking identity predicted Persistence. In contrast, explicit measures of alcohol-approach inclinations, but not implicit measures, predicted both demand indices. Therefore, there was more support for explicit, versus implicit, measures as unique predictors of alcohol demand. Overall, drinking identity and alcohol-approach inclinations both exhibit positive associations with alcohol demand and represent potentially modifiable cognitive constructs that may underlie elevated demand in college student drinkers.

Keywords: Alcohol, behavioral economics, demand, drinking identity, alcohol-approach inclinations

Behavioral economic measures of motivation for alcohol include demand curve indices that reflect the decisions to purchase and consume alcohol at varying unit prices. To date, studies demonstrate that demand indices predict alcohol-related problems above and beyond other established predictors (Skidmore, Murphy, & Martens, 2014; Teeters & Murphy, 2015; Teeters, Pickover, Dennhardt, Martens, & Murphy, 2014), and may be a marker of treatment response (Dennhardt, Yurasek, & Murphy, 2015; Murphy et al., 2015). Identifying cognitive mechanisms that underlie demand-based decision-making may further inform models of risk for alcohol misuse, and potentially, intervention strategies. Two promising cognitive constructs include drinking identity (i.e., associating the self with drinking) and alcohol-approach associations (i.e., the extent to which one approaches versus avoids alcohol). Both constructs predict multiple drinking outcomes, including consumption, craving, problems, and risk of alcohol use disorders (e.g., Lindgren, Foster, Westgate, & Neighbors, 2013a; Lindgren et al., 2013b, 2015a). The current study, therefore, examined drinking identity and alcohol-approach inclinations as predictors of alcohol demand.

Behavioral Economic Demand for Alcohol

Behavioral economic approaches measure value or motivation by determining the amount of behavior or other resource (e.g., time, money) that an organism will allocate towards obtaining a given commodity (Bickel, Marsch, & Carroll, 2000). Demand is a common measure of motivation, and is defined by the relative amount of effort or money a person is willing to spend on the substance (Heinz, Lilje, Kassel, & de Wit, 2012; Murphy, Correia, Colby, & Vuchinich, 2005), as well as the level of consumption across a range of drug prices. Therefore, elevated demand reflects decisions to consume large amounts of a substance, to spend considerable resources on the substance overall, and/or to continue to consume a substance as the cost to do so increases.

Demand curve indices can be derived from hypothetical self-reported purchase tasks, such as the Alcohol Purchase Task (APT; Murphy & MacKillop, 2006), in which participants specify how much of the substance they would purchase and use across a range of prices. Several estimates of demand are derived from these data and represent two underlying latent variables: Amplitude, which represents the maximum spent and consumed, and Persistence, which represents sensitivity to increasing price value (Bidwell, MacKillop, Murphy, Tidey, & Colby, 2012; MacKillop et al., 2009). Demand indices have been linked to greater levels of drinking and alcohol-related problems (Skidmore et al., 2014; Teeters et al., 2014), and various metrics generated from demand curves predict response to brief alcohol interventions (Dennhardt et al., 2015; MacKillop & Murphy, 2007; Murphy et al., 2015). Although demand indices are moderately correlated with measures of substance use, they are not redundant (Murphy & MacKillop, 2006; Murphy, MacKillop, Skidmore, & Pederson, 2009). Research suggests that Amplitude is a robust predictor of alcohol consumption whereas Persistence is a robust predictor of prospective drinking following treatment (Dennhardt et al., 2015; MacKillop et al., 2009). Overall, measures of alcohol demand may provide clinically relevant indicators of the strength of desire for substances.

Alcohol-Approach Inclinations and Drinking Identity

Alcohol-approach inclinations and drinking identity are two promising cognitive constructs that may underlie elevated demand for alcohol. Alcohol-approach inclinations have been studied extensively as predictors of alcohol use and are positively associated with retrospective and prospective drinking reports (Farris, Ostafin, & Pailfai, 2010; McEvoy, Stritzke, French, Lang, & Ketterman, 2004; Ostafin & Palfai, 2006), and alcohol consumption in the laboratory (Ostafin, Marlatt, & Greenwald, 2008). Further, intervention studies demonstrate that alcohol-approach inclinations can be modified and lead to improved treatment outcomes (Eberl et al., 2013; Wiers, Eberl, Rinck, Becker, & Lindenmeyer, 2011; but see also Lindgren et al., 2015b). The extensive examination of alcohol-approach inclinations stems from the prevalence of similar motivational constructs among theories of substance misuse, including incentive sensitization theory (Robinson & Berridge, 1993), and behavioral economic theory (e.g., Bickel, Johnson, Koffarnus, MacKillop, & Murphy, 2014). Whereas incentive sensitization theory focuses exclusively on appetitive alcohol approach inclinations that lead to alcohol consumption itself, behavioral economic models highlight both individual factors (e.g., approach inclinations) and environmental factors (e.g., availability of alternative reinforcers) that influence decisions to spend resources on alcohol. Therefore, alcohol-approach inclinations represent a point of convergence between models and may be a construct that not only underlies alcohol consumption, but also underlies alcohol demand.

Drinking identity, or the extent to which one associates alcohol with the self, is also a promising cognitive risk factor for hazardous drinking that has been shown to predict alcohol consumption, craving, alcohol-related problems (Lindgren et al., 2013b), risky drinking practices (Gray, LaPlante, Bannon, Ambady, & Shaffer, 2011), and heavy episodic drinking (McClure, Stoolmiller, Tanski, Engels, & Sargent, 2013). Drinking identity is conceptualized as a higher-order construct that coalesces from one’s direct experiences with alcohol and one’s environment, including one’s cultural context (see Back, Schmukle, & Egloff, 2009). Perceptions of identity are believed to act as a source of information in instances of decision-making and action planning (Hagger, Anderson, Kyriakaki & Darkings, 2007), and meta-analyses exhibit large correlations between self-identity and behavioral intention (Rise, Sheeran, & Hukkelberg, 2010). Thus, drinking identity could influence various aspects of demand. For example, individuals with strong drinking identities may make identity-congruent decisions to consume and spend greater quantities of resources on alcohol (Amplitude), and may make identity-congruent decisions to continue to drink as the cost to do so increases (Persistence). However, despite the proposed influence of identity on decision-making in social psychology, no research has examined how drinking identity is related to decisions to drink alcohol as a function of cost.

Two types of measures are commonly used to assess these constructs. The first type, explicit measures, refers to self-report measures (questionnaires) that ask participants to report on their cognitions (e.g., how much do you approach alcohol, how much is drinking part of who you are) and, therefore, assume that these cognitions are accessible for introspection. The second type, implicit measures, does not require participant awareness and include computerized, reaction time (RT) tasks, such as the Implicit Association Test (IAT; Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998). The IAT evaluates the relative strength of automatic associations between pairs of categories held in memory (e.g., alcohol and approach vs. water and avoid) – automatic in the sense of being less consciously controllable. Although explicit and implicit measures may be used to assess the same general construct, meta-analyses have found that they are modestly related (r = .23, Reich, Below, & Goldman, 2010), and that each predicts unique variance in outcomes (general: Greenwald, Poehlman, Uhlmann, & Banaji, 2009; substance use: Reich et al., 2010). Given that implicit and explicit measures are not redundant, measurement of both may provide a more complete account of cognitive factors viewed as determinants of alcohol demand.

Current Study

To date, demand indices have been predominantly examined as predictors of drinking outcomes (MacKillop et al., 2010a; Murphy et al., 2009), and as outcomes to examine situational influences on alcohol demand such as stress, craving/cue exposure, or alternative reinforcers (Amlung & MacKillop, 2014; MacKillop et al., 2010b; Murphy et al., 2005; Rousseau, Irons, & Correia, 2011; Skidmore & Murphy, 2011). Research that focuses on cognitive mechanisms underlying demand is scarce (for exceptions, see Kiselica & Borders, 2013; Yurasek et al., 2011) and is critical given findings that demand indices are robust predictors of alcohol consumption (Murphy & MacKillop, 2006) and recently, treatment response (Murphy et al., 2015). Alcohol-approach inclinations and drinking identity are promising cognitive factors that might influence demand. If that is demonstrated, integrating those cognitive constructs with behavioral economic theory could lead to improved models of young adult alcohol misuse.

The current study examined repeated implicit and explicit measures of drinking identity and alcohol-approach inclinations as predictors of alcohol demand indices. Repeated measures allowed for more precise and reliable assessments of the implicit and explicit constructs1. Our first study aim was to individually examine each measure of drinking identity and alcohol-approach inclinations as predictors of demand. We hypothesized that implicit and explicit measures of drinking identity and alcohol-approach inclinations would positively predict demand indices. Our second aim was to examine the unique predictive values of implicit and explicit measures when included in the same model. We hypothesized that each drinking identity measure would predict unique variance in each demand index. However, given findings that explicit, but not implicit, measures of alcohol-approach inclinations uniquely predicted alcohol-related problems (Lindgren et al., 2013b), we predicted that explicit alcohol-approach inclinations would be stronger predictors of demand indices compared to implicit alcohol-approach inclinations. We did not hypothesize that any measure would differentially predict distinct demand indices. Finally, exploratory analyses were run to evaluate potential sex differences in findings.

Method

Participants and institutional review

A random sample of students from a large public university in the Pacific Northwest was invited via email to participate in a two-year longitudinal study. Participants were eligible if they were full-time students in their first or second year of college and fluent in English. Contact information for students who fit these criteria was provided by the university’s registrar’s office, and the first 500 students that responded to an invitation email and completed the baseline assessment were enrolled in the study. There were no exclusionary criteria involving alcohol consumption for the larger study, however participants were only included in current analyses if they reported consuming alcohol in the three months prior to beginning the study. The university’s institutional review board approved all procedures and measures. All participants completed online informed consent procedures before beginning the study.

Procedures

Participants completed online study measures as part of an ongoing two-year study investigating changes in implicit cognitions and drinking behavior among college students. The data described here come from the first three timepoints (Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3) separated by three-month intervals. All of the following measures were administered at each timepoint with the exception of the Alcohol Purchase Task administered only at Time 3. The order in which measures were administered was randomized across participants. To check for reliable reporting, participants completed four “check questions” at each timepoint in which participants were instructed to choose a specific response option from a set of multiple options. Participants’ data that included two or more incorrect responses were removed from analyses for that particular timepoint (<1% of data). To increase the odds that the same participant completed the survey measures at each timepoint, email and text reminders were sent to each individual, participants were provided with unique pin codes to access the survey measures, and participants indicated their name and address at each timepoint, which was checked for consistency. Participants received a $25 check by mail for their participation at each timepoint.

Measures

Implicit measures

Implicit alcohol-approach inclinations and drinking identity were assessed using two variants of the IAT (Greenwald et al., 1998). The IAT is a computer based task and administered online. Conceptually, the IAT is used to measure the relative strength of associations between concepts in memory (e.g., is alcohol more strongly related to approach or avoid). In an IAT, participants are tasked with sorting stimuli into categories (e.g., an image of a beer is sorted into the alcohol category, the word “toward” is sorted into the approach category) and to do so as quickly as possible. The IAT score evaluates how quickly the sorting is done when categories are paired (e.g., when the category alcohol is paired with the category approach vs. when it is paired with the category avoid). The difference in sorting time is believed to be a reflection of the strength of the associations (i.e., if one is faster at sorting when alcohol and approach are paired vs. when alcohol and avoid are paired, one is thought to have stronger alcohol approach inclinations).

Each IAT includes seven blocks, and participants are instructed to respond as quickly as possible while trying to not make sorting errors. Blocks 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 have 20 trials; Blocks 4 and 7 have 40 trials. The alcohol approach IAT is used to illustrate. In Blocks 1 and 2, participants practice sorting the stimuli into categories; those blocks are not used in the IAT score. For example, in Block 1, participants sort stimuli as belonging to the alcohol or water category. The category labels are displayed on the top of the screen: alcohol is on the left, water is on the right. Images of alcohol or water are individually presented in the center of the screen, and participants sort the stimuli using a key on the left side of the keyboard (“e” to indicate the image is an alcohol image) and a key on the right side of the keyboard (“i” to indicate the image is a water image). Participants must correct any errors to advance to the next trial. In Block 2, participants sort stimuli as belonging to the approach or avoid category. The same format is used: the label approach is on the top left and the label avoid on the top right; stimuli are presented individually; and stimuli are sorted using the “e” or “i” keys. Block 3 is a combined category block: the category labels alcohol and approach are displayed on the top left and water and avoid are displayed on the top right. Stimuli are again presented individually (they represent all four categories and are randomized). Participants sort the stimuli using same left and right keys (“e” to indicate alcohol or approach stimuli, “i” to indicate water or avoid stimuli). Block 4 is the same but with more trials. Block 5 is a new practice block with a single set of categories (akin to Block 1) but their location has reversed. Now, water is on the left and alcohol is on the right. Blocks 6 and 7 are similar to Blocks 3 and 4, but with different pairings. Water and approach are on the left (and stimuli representing them are sorted using the “e” key) and alcohol and avoid are on the right (and stimuli representing them are sorted using the “i” key). To minimize order effects, the order of the combined categories (i.e., alcohol paired with approach & water paired with avoid vs. alcohol paired with avoid and water paired with approach) is counterbalanced across participants.

IAT scores were calculated using the D score algorithm (Greenwald, Nosek, & Banaji, 2003). The D score is a standardized difference score of the average sorting time across the combined categories (i.e., the average reaction time for the trials in the Blocks 3 and 4 subtracted from the average reaction time for the trials in Blocks 6 and 7). IATs were scored such that higher scores indicate stronger associations with the concepts in the IAT’s name (e.g., for the alcohol-approach IAT, higher scores indicate being faster at sorting stimuli when alcohol and approach [and water and avoid] were paired than when alcohol and avoid [and water and approach] were paired).

Two IAT were used in the present study: alcohol approach and drinking identity. The alcohol-approach IAT (Palfai & Ostafin, 2003) stimuli included: pictures of alcohol, pictures of water, words representing approach (approach, closer, advance, forward, toward), and words representing avoid (avoid, away, leave, withdraw, escape). The alcohol stimuli were personalized: participants selected four images depicting the types of alcoholic beverages they consume most frequently; the four water images were standardized (per Lindgren et al., 2013b). The drinking identity IAT (Lindgren et al., 2013b), which evaluates the associations among the concepts of drinker, nondrinker, me and not me, used the following words as stimuli: me, mine, my, self (me stimuli); they, their, them, others (not me stimuli); drinker, drink, drunk, partier (drinker stimuli); and nondrinker, abstain, sober, abstainer (nondrinker stimuli). The drinking identity IAT score is thought to reflect how strongly me and drinker (and not me and nondrinker) are associated in memory relative to me and nondrinker (and not me and drinker).

Data were first screened for possible exclusion if participant response times were faster than 300 milliseconds for 10% or more of the trials or if participant error rates were greater than 20% (see Nosek et al., 2007). Four percent of the IAT scores were excluded from analyses. Internal consistencies for the IATs represent correlations between D scores from Blocks 3 and 6 and Blocks 4 and 7, which typically range from .5 to .7 (Greenwald et al., 2003). Correlations for the alcohol-approach IAT at Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3 were .54, .49, and .49, respectively. Correlations for the drinking identity IAT at Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3 were .56, .57, and .56, respectively.

Explicit measures

Explicit drinking identity was assessed using the Alcohol Self Concept Scale (ASCS; Lindgren et al., 2013b), an adaptation of the Smoker Self Concept Scale (Shadel & Mermelstein, 1996). The ASCS is a five-item measure in which participants rate their agreement with statements regarding how much drinking is a part of one’s self-concept and personality (e.g., Drinking is part of “who I am”). Cronbach’s alphas for Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3 were .91, .91, and .96, respectively. Explicit alcohol-approach inclinations were measured using the inclined/indulgent subscale of the Approach and Avoidance of Alcohol Questionnaire (AAAQ; McEvoy et al., 2004). This subscale contains five items in which participants rate their agreement with statements regarding one’s approach inclinations to alcohol (e.g., My desire to drink seemed overwhelming) in the preceding week. This subscale was used because of its face validity, and because of stronger correlation with the alcohol-approach IAT compared to other AAAQ subscales. Cronbach’s alphas for Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3 were .92, .90, and .90, respectively.

Alcohol use behaviors

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001) was administered to characterize the sample based on hazardous and harmful patterns of alcohol use at Time 1. The AUDIT consists of 10 questions rated on 0–4 scales based on three domains; hazardous alcohol use, dependence symptoms, and harmful alcohol use. Total scores on the AUDIT range from 0–40, with scores of 8 or higher indicating levels of potentially hazardous or harmful drinking (Babor et al., 2001). Cronbach’s alpha for Time 1 was .82. Drinking levels were assessed using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) indicating the average weekly number of standard drinks consumed for the three months preceding Time 1. Prior to completing the DDQ, participants were provided information indicating common standard drink equivalencies. The DDQ has been used frequently with college students and is highly correlated with self-monitored drinking reports (Kivlahan, Marlatt, Fromme, Coppel, & Williams, 1990).

Alcohol demand

The Alcohol Purchase Task (APT; Murphy & MacKillop, 2006) was used to measure demand for alcohol by assessing self-reported alcohol consumption and financial expenditure across a range of drink prices in a hypothetical scenario (at a bar to see a band). Participants reported the number of standard drinks they would consume during the specified time frame (5 hours) at 19 price increments ranging $0 to $20 per drink. Demand curves were estimated by fitting each participant’s reported consumption across the range of prices to Hursh and Silberberg’s (2008) equation: log Q = log Q0 + k(e−αP − 1) , where Q represents the quantity consumed, Q0 represents consumption at price = 0, k specifies the range of the dependent variable (alcohol consumption) in logarithmic units, P specifies price, and α specifies the rate of change in consumption with changes in price (elasticity). Several measures were generated from the demand curve: 1) breakpoint (first price at which alcohol consumption is zero); 2) intensity of demand (alcohol consumption at the lowest price), 3) Omax (maximum financial expenditure on alcohol); 4) Pmax (price at which expenditure is maximized); and 5) elasticity of demand (sensitivity of alcohol consumption to increases in cost). Research indicates that these indices can be combined to create composite variables that are associated with alcohol variables and may further increase reliability (MacKillop et al., 2009). Amplitude represents the maximum spent and consumed and is composed of intensity and Omax. Persistence represents the sensitivity to increasing price value and is composed of elasticity, Pmax, breakpoint, and Omax (MacKillop et al., 2009). The APT has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of alcohol demand that is highly correlated with actual laboratory drink purchases (Amlung & MacKillop, 2015), is highly stable over a 2-week period (Murphy et al., 2009), and predicts changes in drinking over time (Murphy et al., 2015).

Analytic plan

Gender comparisons on demographic and other individual differences measures were conducted using independent samples t-tests. We used growth-curve models to test the primary aims of our study. All predictor and outcome variables were standardized prior to analyses, and all models were estimated using R version 3.1.2, lavaan package version 0.5–17 (Rosseel, 2012) using maximum likelihood estimation. First, latent growth models with time coded 0, 1, and 2 were estimated to examine linear growth in each implicit and explicit measure of drinking identity and alcohol-approach across the three timepoints. There was no evidence of growth in any measure (ps > .10), and as a result, random intercept-only models (i.e., composite score in a measure across the three timepoints) were used to predict the Amplitude and Persistence indices of the APT. An advantage of these models is that measurement error is averaged across multiple timepoints, which increases reliability of the implicit and explicit measures in the model (Kline, 2010). This may be particularly beneficial to implicit measures because they are subject to measurement error and exhibit lower internal consistencies than self-report questionnaires (Ataya et al., 2012). We fit four individual models that addressed our first aim to examine the relationship between each implicit and explicit cognitive measure and demand indices separately (see Figure 1). We then fit two combined models that included an implicit measure and its explicit counterpart (i.e., implicit and explicit drinking identity) to address our second aim of examining each measure’s unique predictive value (see Figure 2). All models included sex, which was dummy coded as 0 for men, and 1 for women. To test whether implicit and explicit measures had significantly different relationships with demand indices in the combined models, we also fit constrained models in which implicit and explicit predictor coefficients were constrained to be equal to each other. We then ran a chi-square difference test of the constrained and the original, unconstrained model fits to test the null hypothesis that implicit and explicit measures have the same relationship with demand indices. Overall model fit was assessed using the chi-square test, comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). General rules of thumb for concluding good model fit include a nonsignificant chi-square, a CFI greater than 0.95, and an RMSEA less than 0.05 (Kline, 2010).

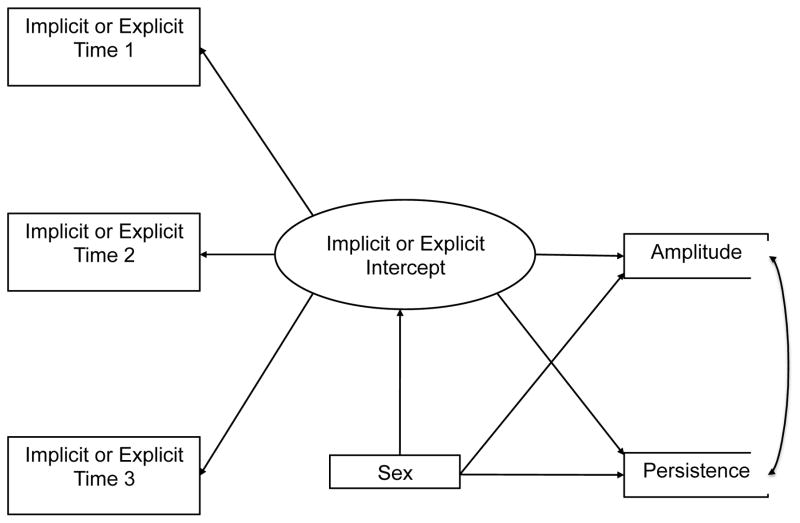

Figure 1.

Illustration of individual models. Four separate models fit either implicit or explicit measures of drinking identity or alcohol-approach inclinations to predict both Amplitude and Persistence. Implicit and explicit measures of drinking identity and alcohol approach inclinations were assessed at three timepoints separated by three-month intervals. Given no evidence of growth over time, random intercept-only models (i.e., intercept reflects the composite score in a measure across the three timepoints) were used to predict Amplitude and Persistence. All models included sex, which was dummy-coded (0 = men, 1 = women).

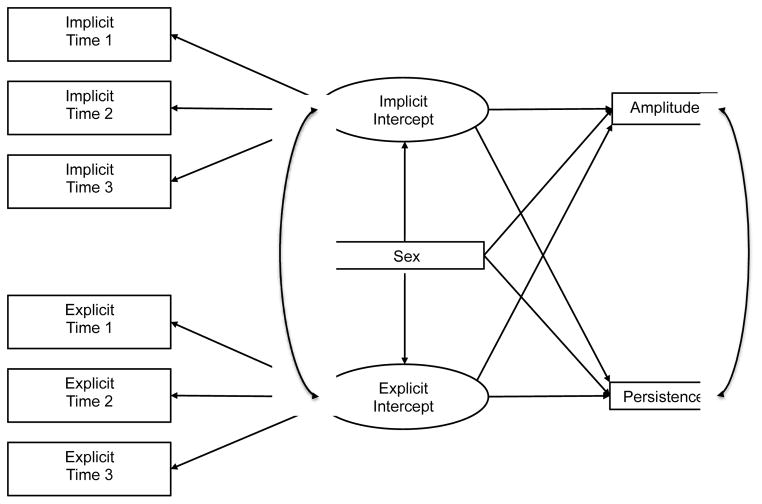

Figure 2.

Illustration of combined models. One model fit both implicit and explicit measures of drinking identity and another model fit both implicit and explicit measures of alcohol-approach inclinations to predict Amplitude and Persistence. Implicit and explicit measures of drinking identity and alcohol approach inclinations were assessed at three timepoints separated by three-month intervals. Given no evidence of growth over time, random intercept-only models (i.e., intercepts reflect composite scores in a measure across the three timepoints) were used to predict Amplitude and Persistence. All models included sex, which was dummy-coded (0 = men, 1 = women).

As exploratory analyses, we used multiple group models to examine whether the relationships between our cognitive measures and demand indices were moderated by sex. For each of the combined models (drinking identity and alcohol-approach) we fit (1) an unconstrained model in which regression coefficients were unconstrained for men and women, and (2) a constrained model in which regression coefficients were constrained to be equal for men and women. We used chi-square difference tests to compare the fit of constrained and unconstrained models. The null hypothesis of the difference test is that the constrained and unconstrained models have equal fit, indicating that implicit and explicit measures of drinking identity and alcohol-approach inclinations have the same relationship with alcohol demand for men and women.

Results

Descriptive statistics and adequacy of demand model fit

Table 1 shows descriptive information for the sample separated by sex. Participants were 223 full-time undergraduate students (92 men, 131 women) between the ages of 18 and 20 (M = 18.6, SD = 0.7) who reported drinking 7.1 (SD = 8.7) mean standard drinks per week in the three months prior to the study. Fifty-six percent of participants identified as White/Caucasian, 28% as Asian, 13% as multiracial, and the remaining 3% as Black/African-American, American Indian, Native Alaskan, or declined to answer. Men reported consuming more standard drinks per week than women [t(219) = 1.96, p = .05], but there were no sex differences in age or AUDIT scores. Table 2 shows bivariate correlations among all variables included in our models.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by Sex: Percentage or Mean (With Standard Deviation in Parentheses)

| Variable | Men (n = 92) | Women (n = 131) | Overall (n = 223) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18.5 (0.7) | 18.6 (0.7) | 18.6 (0.7) |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 60.7 | 52.7 | 55.9 |

| African-American | 0.0 | 2.3 | 1.4 |

| Asian | 25.8 | 29.0 | 27.7 |

| American Indian/Native Alaskan | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.9 |

| More than one race | 13.5 | 12.9 | 13.2 |

| Unknown | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.9 |

| Hispanica | 5.6 | 6.8 | 6.2 |

| AUDIT | 5.9 (5.3) | 5.8 (5.0) | 5.8 (5.1) |

| Standard Drinks Per Weekb | 8.5 (11.1)c | 6.2 (6.4)c | 7.1 (8.7) |

Note. All measures assessed at Time 1;

Ethnicity and race were not mutually exclusive;

Derived from the Daily Drinking Questionnaire;

t(219) = 1.96, p = .05;

AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (scores on 0–40 scale, with scores 8 or above indicating hazardous and harmful alcohol use, Babor et al., 2001).

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix for Outcome and Predictor Variables

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | — | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Implicit DI - T1 | −.11 | — | |||||||||||||

| 3. Implicit DI - T2 | −.13 | .45** | — | ||||||||||||

| 4. Implicit DI - T3 | −.19** | .47** | .51** | — | |||||||||||

| 5. Explicit DI - T1 | −.06 | .20** | .14* | .23** | — | ||||||||||

| 6. Explicit DI - T2 | −.06 | .28** | .18* | .16* | .67** | — | |||||||||

| 7. Explicit DI - T3 | −.05 | .19** | .17* | .13 | .44** | .53** | — | ||||||||

| 8. Implicit AA - T1 | −.13 | .13 | .16* | .11 | .13 | .12 | .00 | — | |||||||

| 9. Implicit AA - T2 | −.24** | .27** | .32** | .27** | .16* | .12 | .12 | .42** | — | ||||||

| 10. Implicit AA - T3 | −.08 | .23** | .27** | .18* | .12 | .21** | .13 | .41** | .48** | — | |||||

| 11. Explicit AA - T1 | −.01 | .44** | .30** | .36** | .37** | .40** | .35** | .19** | .19** | .20** | — | ||||

| 12. Explicit AA - T2 | −.04 | .34** | .23** | .20** | .25** | .37** | .35** | .11 | .20** | .15* | .65** | — | |||

| 13. Explicit AA - T3 | −.08 | .39** | .29** | .29** | .20** | .34** | .33** | .16* | .19** | .29** | .55** | .64** | — | ||

| 14. Amplitude | −.17* | .33** | .19** | .17* | .26** | .26** | .35** | .13 | .21** | .17* | .46** | .45** | .50** | — | |

| 15. Persistence | .01 | .15* | .17* | .03 | .18* | .15* | .20** | .14* | .08 | .09 | .34** | .32** | .38** | .68** | — |

Note. Sex was dummy-coded (0 = men, 1 = women); DI = Drinking Identity (higher scores indicate stronger drinker identities); AA = Alcohol-Approach (higher scores indicate greater alcohol-approach inclinations); all implicit and explicit measures were assessed at each of three timepoints, designated here as T1, T2, and T3; Amplitude and Persistence were derived from the Alcohol Purchase Task at T3;

p < .05,

p < .01.

The exponential demand equation (Hursh & Silberberg, 2008) provided an excellent fit (R2= .97) for the aggregated data (i.e., sample mean consumption values) and a good fit for individual participant data (mean R2 = .82). The authors used a similar criterion as Reynolds and Schiffbauer (2004) and included values for analyses only when the equation accounted for at least 30% of the variance (one participant was excluded due to this criterion).

Random intercept models

Drinking identity

Results for all random intercept models are shown in Table 3. To test our first aim, implicit and explicit measures of drinking identity were first analyzed as predictors of demand indices in separate models. Fit indices suggested good fit for the explicit drinking identity model [χ2(10) = 17.16, p = .07, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .05] and good fit for the implicit drinking identity model [χ2(10) = 16.39, p = .09, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .06]. In the individual models, stronger implicit drinking identity was significantly associated with greater Amplitude (standardized β = 0.35, p < .001) and greater Persistence (β = 0.22, p = .018). Stronger explicit drinking identity was also significantly associated with greater Amplitude (β = 0.36, p < .001) and greater Persistence (β = 0.22, p = .005). The combined model tested our second aim and results suggested that both implicit and explicit measures of drinking identity account for unique variance in alcohol demand. Fit indices suggested excellent fit for the combined model that included both implicit and explicit measures [χ2(29) = 35.37, p = .23, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .03]. Stronger implicit drinking identity was significantly associated with greater Amplitude (β = 0.26, p = .003), but was not significantly associated with Persistence (β = 0.16, p = .09). Stronger explicit drinking identity was significantly associated with both greater Amplitude (β = 0.30, p < .001) and greater Persistence (β = 0.20, p = .017). A comparison of the constrained and unconstrained models suggests that explicit and implicit measures have similar relationships with demand indices. Specifically, the unconstrained combined model with unique implicit and explicit predictor effects for demand indices did not significantly fit the data better than the constrained model with equal implicit and explicit predictor effects [Δχ2(2) = .05, p = .98].

Table 3.

Random Intercept Models Predicting Alcohol Demand Curve Indices

| Predictors | Amplitude

|

Persistence

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE β | p | β | SE β | p | |

| Drinking Identity Individual Models | ||||||

| Implicit Drinking Identity | 0.35 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.22 | 0.09 | .018 |

| Sex | −0.10 | 0.08 | .194 | 0.05 | 0.08 | .501 |

| Explicit Drinking Identity | 0.36 | 0.07 | <.001 | 0.22 | 0.08 | .005 |

| Sex | −0.14 | 0.07 | .030 | 0.04 | 0.07 | .572 |

| Drinking Identity Combined Model | ||||||

| Implicit Drinking Identity | 0.26 | 0.09 | .003 | 0.16 | 0.09 | .087 |

| Explicit Drinking Identity | 0.30 | 0.08 | <.001 | 0.20 | 0.08 | .017 |

| Sex | −0.13 | 0.07 | .092 | 0.04 | 0.08 | .643 |

| Alcohol Approach Individual Models | ||||||

| Implicit Alcohol Approach | 0.28 | 0.09 | .002 | 0.19 | 0.09 | .039 |

| Sex | −0.10 | 0.08 | .213 | 0.10 | 0.08 | .217 |

| Explicit Alcohol Approach | 0.59 | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.44 | 0.07 | <.001 |

| Sex | −0.16 | 0.06 | .006 | 0.04 | 0.06 | .563 |

| Alcohol Approach Combined Model | ||||||

| Implicit Alcohol Approach | 0.11 | 0.08 | .167 | 0.07 | 0.09 | .425 |

| Explicit Alcohol Approach | 0.55 | 0.07 | <.001 | 0.39 | 0.08 | <.001 |

| Sex | −0.15 | 0.07 | .035 | 0.08 | 0.08 | .309 |

Note. Values represent standardized coefficients; Sex was dummy-coded (0 = men, 1 = women); Implicit Drinking Identity = Drinking Identity Implicit Association Task; Explicit Drinking Identity = Alcohol Self-Concept Scale; Implicit Alcohol Approach = Alcohol-Approach Implicit Association Task; Explicit Alcohol Approach = Alcohol Approach and Avoidance Questionnaire.

Alcohol-approach

Next, implicit and explicit measures of alcohol-approach were analyzed as predictors of demand indices in separate models. Fit indices indicated an excellent fit to the implicit alcohol-approach model [χ2(10) = 11.27, p = .34, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .03] and an excellent fit to the explicit alcohol-approach model [χ2(10) = 11.20, p = .34, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .02]. Stronger implicit alcohol-approach inclinations were significantly associated with greater Amplitude (β = 0.28, p = .002) and greater Persistence (β = 0.19, p = .039). Similarly, stronger explicit alcohol-approach inclinations were significantly associated with greater Amplitude (β = 0.59, p < .001) and greater Persistence (β = 0.44, p < .001). In the combined model, only explicit alcohol-approach inclinations significantly predicted alcohol demand. Fit indices indicated an excellent fit to the combined model [χ2(29) = 36.48, p = .19, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .04]. Stronger explicit alcohol-approach inclinations were significantly associated with greater Amplitude (β = 0.55, p < .001) and greater Persistence (β = 0.39, p < .001), whereas implicit alcohol-approach inclinations were not significantly associated with either demand index (ps > .05). This pattern was further supported by a comparison of the constrained and unconstrained models. Specifically, the original unconstrained model with unique implicit and explicit predictor effects for demand indices fit the data significantly better than the constrained model with equal implicit and explicit predictor effects [Δχ2(2) = 9.32, p = .009], suggesting that explicit alcohol-approach inclinations are stronger predictors of demand.

Exploratory sex comparisons

Unconstrained models that allowed regression coefficients to vary between sexes did not significantly fit the data better than constrained models in which regression coefficients were constrained to be equal across sexes for either the combined drinking identity model [Δχ2(4) = 8.78, p = .07], or the combined alcohol-approach model [Δχ2(4) = 6.29, p = .18].

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate implicit and explicit measures of two cognitive constructs, drinking identity and alcohol-approach inclinations, as predictors of alcohol demand curve indices, and is the first study we know of that does so. Two sets of models were run to (1) individually examine each implicit and explicit measure of our constructs as predictors of alcohol demand, and (2) examine the unique predictive value of implicit and explicit measures when included in combined models. Several important findings emerged.

When considered individually, implicit and explicit measures of drinking identity were significantly associated with both demand indices. Results are consistent with conceptualizations that view identity as a source of information that guides behavior and intentions (Hagger et al., 2007). Therefore, a possible explanation for the findings is that drinking identities provide information for individuals when faced with demand-based questions (i.e., How much money should I spend on alcohol overall? Should I buy a $10 drink?). As measured by the APT, students with stronger drinking identities made identity-congruent decisions to consume greater amounts and spend more overall resources on alcohol (Amplitude), and to continue to drink as the cost to do so increased (Persistence). A key advantage of behavioral economic models is the synthesis of perspectives from psychology, economics, and cognitive neuroscience. These perspectives identify a number of individual-level factors (e.g., alcohol expectancies, drinking motives) believed to influence the decision-making process underlying alcohol consumption as a function of costs (Bickel et al., 2014; Mackillop, 2016). To date however, none recognize one’s identity as a factor despite the importance of identity as a construct among multiple domains of psychology research. The current study suggests that the inclusion of one’s identification with drinking as an influence on demand may strengthen existing models.

With regard to the contributions of implicit and explicit measures of drinking identity, both types accounted for unique variance in Amplitude, but only explicit measures were uniquely associated with Persistence. It is possible that as the cost to drink increases, individuals require more controlled cognitive processes to weigh the costs and benefits of continued drinking. If so, drinking identity that is under conscious control, and available for explicit self-report, may be more closely related to Persistence. It should be noted however, that the combined, unconstrained model did not provide a significantly better fit to the data than a model in which implicit and explicit coefficients were constrained to be equal to each other indicating that implicit and explicit drinking identity are similarly associated with alcohol demand. Overall, the results demonstrate that the extent to which one identifies with drinking is associated with alcohol demand, however further work is needed to determine whether implicit measures of drinking identity uniquely predict persistence in spending money when prices per drink escalate.

When evaluated individually, implicit and explicit measures of alcohol-approach inclinations were also significantly associated with both demand indices. These findings corroborate previous research indicating positive associations between similar measures, like self-reported craving, and demand (MacKillop et al., 2010a), and also extend the findings by demonstrating that implicit measures of alcohol-approach are associated with demand when considered on their own. These findings support existing theoretical foundations for behavioral economic models, and in particular, principles of operant learning theory that conceptualize alcohol use as an operant behavior maintained by alcohol’s reinforcing properties (MacKillop, 2016). From this perspective, alcohol demand is thought to reflect the degree to which alcohol is considered reinforcing for an individual, and is sometimes referred to as relative reinforcing value. Another principle from operant learning theory is that a reinforcer not only increases the probability of a consummatory behavior (e.g., alcohol consumption), but also may result in approach or appetitive behavior toward the reinforcer itself. Therefore, the current findings support these theoretical principles and may also offer some convergence between behavioral economic and incentive-sensitization models of alcohol misuse (Robinson & Berridge, 1993) to the extent that alcohol-approach inclinations are related to actual alcohol consumption (e.g., McEvoy et al., 2004) and the aspects of demand that reflect resources spent on alcohol.

With regard to the unique contributions of implicit and explicit alcohol-approach measures, when both were included in the same model, only explicit measures accounted for unique variance in demand indices, and they exhibited larger effect sizes. Additionally, an unconstrained model with unique implicit and explicit predictor effects fit the data significantly better than a model in which implicit and explicit predictor effects were constrained to be equal to each other, further suggesting that explicit measures were more strongly associated with demand. Therefore, alcohol-approach inclinations measured by self-report that are consciously accessible to an individual, may be better indicators of overall demand for alcohol among college student drinkers. Consistent with this pattern of results, previous studies with college students along the full range of drinking (i.e., abstainers to heavy drinkers) have shown that explicit measures of alcohol-approach inclinations predicted unique variance in alcohol-related problems, whereas there was only marginal evidence of implicit alcohol-approach inclinations as unique predictors of problems (Lindgren et al., 2013b). It is important to note that the current sample consists of students in their first or second years of college and presumably have fewer drinking experiences than typical heavy drinking samples. Further research should examine whether implicit alcohol-approach inclinations are more important among individuals who have longer learning histories necessary to develop stronger associations.

Another contribution of the current study was to explore potential sex differences in the relationships between cognitive constructs and demand indices. Neither drinking identity nor alcohol-approach inclinations had significantly different relationships with demand indices for men and women in the study. Although previous research has found that men have stronger alcohol-approach associations (Lindgren, Neighbors, Ostafin, Mullins, & George, 2009), and drinking identities (Werntz, Steinman, Glenn, Nock, & Teachman, 2016), the current study found no meaningful differences in the relationships between these variables and demand. However, given the exploratory nature of these analyses, further research is necessary to determine whether cognitive factors differ in the prediction of alcohol demand for men and women.

Study limitations include the fact that the sample was comprised of full-time college students who at a minimum reported alcohol consumption in the past month (sample reported consuming 7.1 mean standard drinks per week). Whether the current results generalize to alcohol dependent individuals or older drinkers with severe alcohol-related problems is unknown and warrants future research. This area of research is important because if drinking identity and alcohol-approach inclinations are found to predict elevated demand among problem drinkers, this would highlight these constructs as potential targets for intervention. An additional limitation is that although the study included repeated measures of cognitive constructs, alcohol demand was assessed at a single timepoint, and longitudinal analyses are needed to explore causal relationships between cognitive constructs and demand indices. For example, the positive association between drinking identity and alcohol demand may reflect a bidirectional relationship. That is, although drinking identity may act as a source of information that influences demand, decisions to spend considerable resources on alcohol may in turn affect the formation of drinking identity. Longitudinal analyses will be necessary to test these possibilities.

In conclusion, this study is the first to evaluate alcohol demand using both implicit and explicit measures of two cognitive constructs: alcohol-approach inclinations and drinking identity. Stronger alcohol-approach inclinations and stronger drinking identities were associated with greater overall hypothetical alcohol consumption and expenditures and greater persistence to consume alcohol as the price to do so escalates. These findings indicate that both constructs represent potential targets of interventions aimed to reduce alcohol demand. The utility of using both implicit and explicit measures was initially supported: all measures of drinking identity and alcohol-approach inclinations were significantly associated with both demand indices when considered individually. However, when evaluating the predictive value of implicit and explicit cognitive measures in concert, not all measures were significantly associated with demand. In general, there was more support for explicit measures as unique predictors of demand, and this was particularly true for alcohol-approach inclinations. Collectively, the results demonstrate that alcohol-approach inclinations and drinking identity are associated with alcohol demand, and that consideration of these two cognitive constructs as influences on demand may improve behavioral economic models of alcohol use among young adults.

Public Significance Statement.

This study found that college students’ decisions to consume and spend money on alcohol are influenced by the extent to which they want to approach alcohol and the extent to which they identify with drinking. The findings suggest that alcohol approach inclinations and drinking identities are important individual-level factors to consider among behavioral economic perspectives of alcohol use and could be targets for intervention among college student drinkers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants R01AA21763 and T32AA007455. The funding sources had no other involvement other than financial support.

Footnotes

Repeated measures also allow for examination of whether the implicit and explicit measures systematically change over time. As we show below, there was no systematic change in the measures. Thus, we used a model-based composite of the repeated measures to increase the reliability and precision of the implicit and explicit measures.

Disclosures

All authors made substantive contributions to the manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

We thank Melissa Gasser for assistance with data collection.

References

- Amlung M, MacKillop J. Understanding the effects of stress and alcohol cues on motivation for alcohol via behavioral economics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:1780–1789. doi: 10.1111/acer.12423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung M, MacKillop J. Further evidence of close correspondence for alcohol demand decision making for hypothetical and incentivized rewards. Behavioural Processes. 2015;113:187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataya AF, Adams S, Mullings E, Cooper RM, Attwood AS, Munafò MR. Internal reliability of measures of substance-related cognitive bias. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;121:148–151. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary care. 2. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Back MD, Schmukle SC, Egloff B. Predicting actual behavior from the explicit and implicit self-concept of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:533–548. doi: 10.1037/a0016229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel W, Johnson M, Koffarnus M, MacKillop J, Murphy JG. The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: Reinforcement pathologies and their repair. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2014;10:641–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA, Carroll ME. Deconstructing relative reinforcing efficacy and situating the measures of pharmacological reinforcement with behavioral economics: a theoretical proposal. Psychopharmacology. 2000;153:44–56. doi: 10.1007/s002130000589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidwell LC, MacKillop J, Murphy JG, Tidey JW, Colby SM. Latent factor structure of a behavioral economic cigarette demand curve in adolescent smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:1257–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennhardt AA, Yurasek AM, Murphy JG. Change in delay discounting and substance reward value following a brief alcohol and drug use intervention. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2015;103:125–140. doi: 10.1002/jeab.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl C, Wiers RW, Pawelczack S, Rinck M, Becker ES, Lindenmeyer J. Approach bias modification in alcohol dependence: do clinical effects replicate and for whom does it work best? Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2013;4:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris SR, Ostafin BD, Palfai TP. Distractibility moderates the relation between automatic alcohol motivation and drinking behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:151–156. doi: 10.1037/a0018294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray HM, LaPlante DA, Bannon BL, Ambady N, Shaffer HJ. Development and validation of the Alcohol Identity Implicit Associations Test (AI-IAT) Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:919–926. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JK. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1464–1480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.6.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Nosek BA, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:197–216. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Poehlman TA, Uhlmann E, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: III. Meta-analysis of predictive validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:17–41. doi: 10.1037/a0015575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagger MS, Anderson M, Kyriakaki M, Darkings S. Aspects of identity and their influence on intentional behavior: Comparing effects for three health behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz AJ, Lilje TC, Kassel JD, de Wit H. Quantifying reinforcement value and demand for psychoactive substances in humans. Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 2012;5:257–272. doi: 10.2174/1874473711205040002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, Silberberg A. Economic demand and essential value. Psychological Review. 2008;115:186–198. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselica AM, Borders A. The reinforcing efficacy of alcohol mediates associations between impulsivity and negative drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74:490–499. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA, Fromme K, Coppel DB, Williams E. Secondary prevention with college drinkers: evaluation of an alcohol skills training program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:805–810. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.58.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren KP, Foster DW, Westgate EC, Neighbors C. Implicit drinking identity: drinker + me associations predict college student drinking consistently. Addictive Behaviors. 2013a;38:2163–2166. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren KP, Neighbors C, Ostafin BD, Mullins PM, George WH. Automatic alcohol associations: gender differences and the malleability of alcohol associations following exposure to a dating scenario. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:583–592. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren KP, Neighbors C, Teachman BA, Baldwin SA, Gasser ML, Kaysen D, Norris J, Wiers RW. Implicit alcohol associations, especially drinking identity, predict drinking over time. 2015a doi: 10.1037/hea0000396. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren KP, Neighbors C, Teachman BA, Wiers RW, Westgate E, Greenwald AG. I drink therefore I am: Validating alcohol-related implicit association tests. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013b;27:1–13. doi: 10.1037/a0027640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren KP, Wiers RW, Teachman BA, Gasser ML, Westgate EC, Cousijn J, … Neighbors C. Attempted training of alcohol approach and drinking identity associations in US undergraduate drinkers: Null results from two studies. PLoS ONE. 2015b;10:e0134642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J. The behavioral economics and neuroeconomics of alcohol use disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40:672–685. doi: 10.1111/acer.13004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Miranda RM, Monti PM, Ray LA, Murphy JG, Rohsenow DJ, … Gwaltney CJ. Alcohol demand, delayed reward discounting, and craving in relation to drinking and alcohol use disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010a;119:106–114. doi: 10.1037/a0017513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Murphy J. A behavioral economic measure of demand for alcohol predicts brief intervention outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Murphy JG, Tidey JW, Kahler CW, Ray LA, Bickel WK. Latent structure of facets of alcohol reinforcement from a behavioral economic demand curve. Psychopharmacology. 2009;203:33–40. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1367-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, O’Hagen S, Lisman SA, Murphy JG, Ray LA, Tidey JW, … Monti PM. Behavioral economic analysis of cue-elicited craving for alcohol. Addiction. 2010b;105:1599–1607. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure AC, Stoolmiller M, Tanski SE, Engels RC, Sargent JD. Alcohol marketing receptivity, marketing-specific cognitions, and underage binge drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37(s1):E404–E413. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01932.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy PM, Stritzke WG, French DJ, Lang AR, Ketterman R. Comparison of three models of alcohol craving in young adults: a cross-validation. Addiction. 2004;99:482–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Correia CJ, Colby SM, Vuchinich RE. Using behavioral theories of choice to predict drinking outcomes. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005;13:93–101. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.13.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Borsari B, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Martens MP. A randomized controlled trial of a behavioral economic supplement to brief motivational interventions for college drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:876–886. doi: 10.1037/a0028763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Yurasek AM, Skidmore JR, Martens MP, MacKillop J, McDevitt-Murphy ME. Behavioral economic predictors of brief alcohol intervention outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1037/ccp0000032. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14:219–227. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Skidmore JR, Pederson AA. Reliability and validity of a demand curve measure of alcohol reinforcement. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:396–404. doi: 10.1037/a0017684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosek BA, Greenwald AG, Banaji MR. The Implicit Association Test at age 7: A methodological and conceptual review. In: Bargh JA, editor. Automatic processes in social thinking and behavior. Psychology Press; 2007. pp. 265–292. [Google Scholar]

- Ostafin BD, Marlatt GA, Greenwald AG. Drinking without thinking: an implicit measure of alcohol motivation predicts failure to control alcohol use. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:1210–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostafin BD, Palfai TP. Compelled to consume: The Implicit Association Test and automatic alcohol motivation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:322–327. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfai TP, Ostafin BD. Alcohol-related motivational tendencies in hazardous drinkers: assessing implicit response tendencies using the modified-IAT. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:1149–1162. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich RR, Below MC, Goldman MS. Explicit and implicit measures of expectancy and related alcohol cognitions: a meta-analytic comparison. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:13–25. doi: 10.1037/a0016556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Schiffbauer R. Measuring state changes in human delay discounting: an experiential discounting task. Behavioural Processes. 2004;67:343–356. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rise J, Sheeran P, Hukkelberg S. The role of self-identity in the theory of planned behavior: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2010;40:1085–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00611.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Research Reviews. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y. Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software. 2012;48:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau GS, Irons JG, Correia CJ. The reinforcing value of alcohol in a drinking to cope paradigm. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadel WG, Mermelstein R. Individual differences in self-concept among smokers attempting to quit: validation and predictive utility of measures of the smoker self-concept and abstainer self-concept. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1996;18:151–156. doi: 10.1007/BF02883391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore J, Murphy JG. The effect of drink price and next-day responsibilities on college student drinking: A behavioral economic analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:57–68. doi: 10.1037/a0021118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore JR, Murphy JG, Martens MP. Behavioral economic measures of alcohol reward value as problem severity indicators in college students. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2014;22:198–210. doi: 10.1037/a0036490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeters JB, Murphy JG. The behavioral economics of driving after drinking among college drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2015;39:896–904. doi: 10.1111/acer.12695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeters JB, Pickover AM, Dennhardt AA, Martens MP, Murphy JG. Elevated alcohol demand is associated with driving after drinking among college student binge drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:2066–2072. doi: 10.1111/acer.12448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werntz AJ, Steinman SA, Glenn JJ, Nock MK, Teachman BA. Characterizing implicit mental health associations across clinical domains. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2016;52:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Eberl C, Rinck M, Becker ES, Lindenmeyer J. Retraining automatic action tendencies changes alcoholic patients’ approach bias for alcohol and improves treatment outcome. Psychological Science. 2011;22:490–497. doi: 10.1177/0956797611400615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurasek AM, Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Buscemi J, McCausland C, Martens MP. Drinking motives mediate the relationship between reinforcing efficacy and alcohol consumption and problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;73:991–999. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]