Abstract

Background

We hypothesized that histogenetic classification of salivary duct carcinoma (SDC) could account for de novo cases and those with morphologic or molecular evidence (PLAG1, HMGA2 rearrangement, amplification) of pleomorphic adenoma (PA).

Methods

SDCs (n=66) were reviewed for morphologic evidence of PA. PLAG1 and HMGA2 alterations were detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). PLAG1 positive cases were tested for FGFR1 rearrangement (by FISH). Thirty-nine cases were analyzed by the Ion Ampliseq Cancer HotSpot panel v2 for mutations and copy number variation in 50 cancer-related genes.

Results

Based on combined morphologic and molecular evidence of PA, four subsets of SDC emerged: 1) carcinomas with morphologic evidence of PA, but intact PLAG1 and HMGA2 (n=22); 2) carcinomas with PLAG1 (n=18), or 3) HMGA2 alteration (n=12); and 4) de novo carcinomas, without morphologic or molecular evidence of PA (n=14). The median disease free survival was 37 months (95% confidence interval, 28.4 – 45.6 months). Disease free survival and other clinicopathologic parameters did not differ by above defined subsets. Combined HRAS/PIK3CA mutations were seen predominantly in de novo carcinomas (5/8 vs 2/31, p = 0.035). ERBB2 copy number gain was not seen in de novo carcinoma (0/8 vs. 12/31, p = 0.08). TP53 mutations were more common in SDC ex PA than in de novo cases (17/31 vs. 1/8, p = 0.033).

Conclusion

The genetic profile of SDC varies with the absence or presence of pre-existing PA and its cytogenetic signature. Most de novo SDCs harbor combined HRAS/PIK3CA mutations and no ERBB2 amplification.

Condensed Abstract

Based on morphologic and molecular (PLAG1 and HMGA2 status) evidence of pleomorphic adenoma, four subsets of salivary duct carcinoma were identified with distinct distribution of potentially targetable genetic alteration. Next generation sequencing revealed that de novo salivary duct carcinomas are characterized by combined HRAS/PIK3CA mutations and absence of ERBB2 copy number gain.

Introduction

Salivary duct carcinoma is one of the most aggressive salivary malignancies with most patients presenting with advanced disease.1–5 The current management of patients with salivary duct carcinoma includes surgical resection followed by radio- and/or chemotherapy. With conventional therapy, more than half of salivary duct carcinoma patients die of disease in three to five years.4, 5

Salivary duct carcinoma is the most common histologic type of carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (PA) and at least half of SDC arise from PA.6–9 PA was the first benign human epithelial neoplasm to be shown to harbor recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities involving Pleomorphic Adenoma Gene 1 (PLAG1) and High Mobility Group A2 (HMGA2).10, 11 It has been recognized that there are several cytogenetically defined subsets of PA, including those with PLAG1 or HMGA2 rearrangements, other rearrangements, and cytogenetically intact. As a reflection of PA diversity, comparable cytogenetic abnormalities were reported in salivary duct carcinoma.7, 12, 13

Presently employed targeted therapeutic modalities including anti-ERBB2 approaches, androgen deprivation therapy, and vemurafenib are characterized by variable clinical benefit.14–17 Recently, additional potentially targetable genetic abnormalities in salivary duct carcinoma were identified, including mutations of the gene encoding p110α catalytic subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PIK3CA), alone or combined with HRAS mutations.14, 18–20

The aim of this study was, first, to correlate PLAG1 and HMGA2 alterations with clinicopathologic features in a large cohort of patients with salivary duct carcinoma. For instance, determining the frequency of PLAG1 and HMGA2 rearrangements in salivary duct carcinoma may help to better understand its origin (de novo vs. ex PA). By the time of clinical presentation, salivary duct carcinoma may overrun the remaining evidence of pre-existing PA. Practically, PLAG1 and HMGA2 alterations may help to distinguish on small biopsies salivary and non-salivary high grade adenocarcinomas, especially the ones with an occult primary.

Second, in order to describe genetic events that may be associated with malignant transformation of PA into salivary duct carcinoma, we aimed to characterize the relationship between the presence of pre-existing PA (as determined by a combination of morphology, PLAG1 and HMGA2 status) and mutations and copy number variations in 50 cancer-related genes.

Materials and Methods

Patients and histologic review

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB# IRB991206). Patients whose samples satisfied the following eligibility criteria were included: surgical resection of primary salivary duct carcinoma, sufficient formalin fixed paraffin embedded material for PLAG1 and HMGA2 fluorescence in situ hybridization studies, and availability of clinical information to characterize disease free survival. A total of 66 patients were included from authors’ institutions from 1996 – 2015. Thirty-nine of these cases were used to achieve the second objective via next generation sequencing.

Tumors were staged according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer.21 Chondroid or myxoid stroma with benign ductal elements and hyalinized hypocellular nodules were accepted as histologic evidence for pre-existing PA.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Immunohistochemistry for p53 (DO-7, monoclonal mouse, dilution 1:100, Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) was performed as per manufacturer’s recommendations. p53 IHC was interpreted as per Boyle et al.19, 22

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

PLAG1 and HMGA2 rearrangements were detected by break-apart FISH probes (Empire Genomics, Buffalo, NY). Sixty to 100 cells per case were analyzed using Leica Biosystems FISH Imaging System (CytoVision FISH Capture and Analysis Workstation, Buffalo Grove, IL). Hyperploidy or amplification (centromeric enumeration probes were not used) was defined as presence of >2 PLAG1 or HMGA2 signals in >75% of cells. PLAG1 and HMGA2 rearrangement status of 27 cases was previously determined and reported.7 FGFR1 FISH was performed as described previously.23

Library Preparation, Sequencing, and Data analysis

DNA extraction and targeted next generation sequencing analysis were performed as described previously.19 Library concentration and amplicon sizes were determined using TapeStation System (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Subsequently, the multiplexed barcoded libraries were enriched by clonal amplification using emulsion PCR on templated Ion Sphere Particles and loaded on Ion 318 Chip. Massively parallel sequencing was carried out on a Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine sequencer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) using the Ion Personal Genome Machine Sequencing 200 Kit v2 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After a successful sequencing reaction, the raw signal data were analyzed using Ion Torrent platform-optimized Torrent Suite™ v4.0.2 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The short sequence reads were aligned to the human genome reference sequence (GRCh37/hg19). Variant calling was performed using Variant Caller v4.0 plugin (integrated with Torrent Suite) that generated a list of detected sequence variations in a variant calling file (VCF v4.1; http://www.1000genomes.org/wiki/analysis/variant%20call%20format/vcf-variant-call-format-version-41). The variant calls were annotated, filtered and prioritized using SeqReporter,24 an in-house knowledgebase and the following publically available databases; COSMIC v68 (http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cancergenome/projects/cosmic/), dbSNP build 137 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/), in silico prediction scores (PolyPhen-2 and SIFT) from dbNSFP light v1.3.25 Sequence variants with at least 300× depth of coverage and mutant allele frequency of >5% of the total reads were included for analysis. Copy number variations were identified by next generation sequencing as described previously.26 ERBB2 gain was defined as > 8 copies and CDKN2A loss was defined as <0.5 copies.

Statistical analysis

The four subgroups were compared with an exact (permutation based) two – tailed chi-square test. P values were adjusted by the method of Benjamini and Hochberg.27 Demographic and clinical comparison among salivary duct carcinoma groups was conducted with the Wilcoxon test for continuous data and Fisher’s exact test or a chi-square test for discrete data. Disease-free survival was compared between Pittsburgh/Southern California Permanente Medical Group and Toronto cohorts with a log rank test.

Results

The clinicopathologic parameters of 66 patients with SDC are summarized in Table 1 (and Supplemental Table S1). Eighty percent of patients were males and most patients presented with clinical stage IV disease arising in the parotid gland. In 3 patients unremarkable pleomorphic adenoma was resected 10, 31, and 33 years prior to the diagnosis of salivary duct carcinoma. The estimated median disease free survival was 37 months (95% confidence interval, 28.4 – 45.6 months).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinicopathologic Features of Patients with Salivary Duct Carcinoma (n=66)

| Clinicopathologic Feature | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender, Male (%) | 53/66 (80%) | |

| Age, mean (range), years | 66 (33–81) | |

| Site | Parotid | 58 (88%) |

| Submandibular | 8 (12%) | |

| Tumor size, mean (range), cm | 3.4 (0.8–7.2) | |

| Origin1 | De novo | 20 (30%) |

| Ex PA | 46 (70%) | |

| pT | 1 | 9 (14%) |

| 2 | 12 (18%) | |

| 3 | 22 (33%) | |

| 4 | 23 (35%) | |

| pN2 | 0 | 6 (9%) |

| 1 | 10 (15%) | |

| 2 | 46 (70%) | |

| p53 IHC | Extreme positive | 20 (30%) |

| Extreme negative | 14 (21%) | |

| Normal | 32 (48%) | |

| PLAG1 positive3, n | 18 (27%) | |

| HMGA2 positive, n | 12 (18%) | |

Based on morphologic evaluation;

pN was unknown for 4 patients;

Positive accounts for rearrangement alone, rearrangement accompanied by copy number gain, or copy number gain alone.

PA, pleomorphic adenoma; IHC, immunohistochemistry

None of the demographic or clinicopathologic parameters of interest (gender, age, tumor site, pathologic or clinical stage, p53 by immunohistochemistry) differed by origin of salivary duct carcinoma (de novo vs ex PA, as defined by morphology) and was not associated with disease free survival (DFS) (p = 0.37). DFS was comparable among patients diagnosed at different institutions (p = 0.49).

Four subsets of salivary duct carcinoma defined by the morphologic evidence of pleomorphic adenoma and PLAG1 or HMGA2

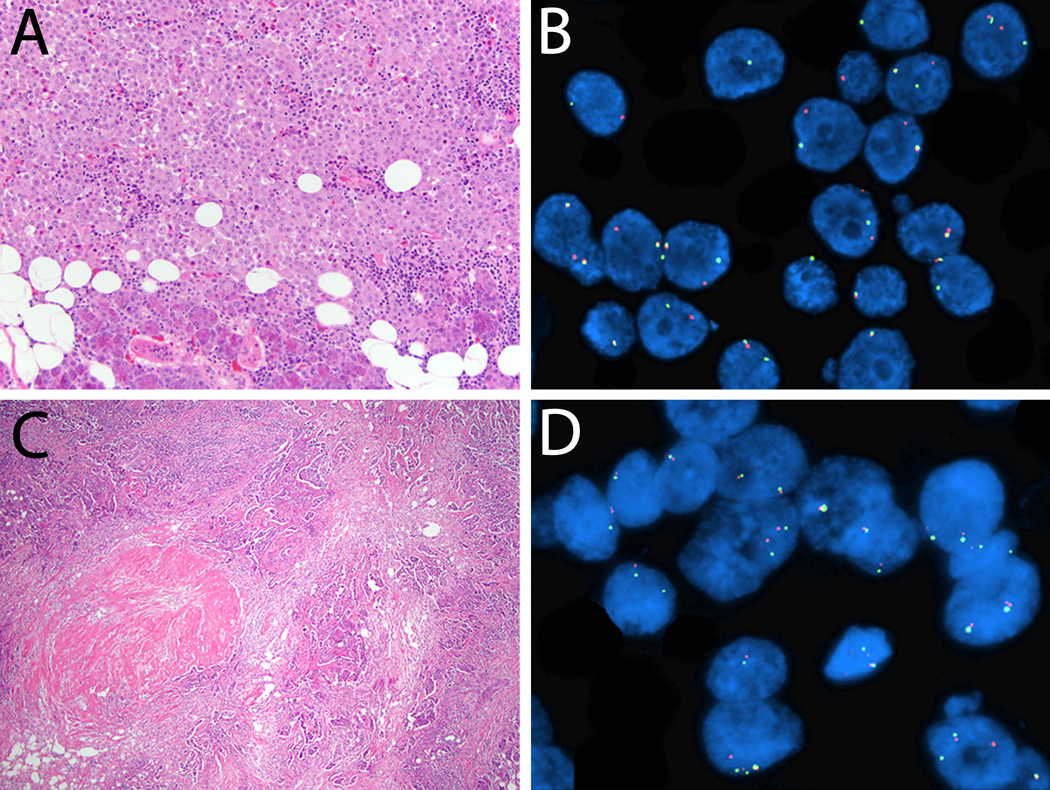

Of 39 salivary duct carcinomas, 13 cases showed PLAG1 alteration, including 7 cases with rearrangement only (Figure 1A–B), 4 cases with rearrangement and hyperploidy, and 2 cases with hyperploidy only. Five cases were characterized by HMGA2 rearrangement, including 4 cases with rearrangement only (Figure 1C–D) and 1 case with rearrangement and hyperploidy.

Figure 1.

A–B. Salivary duct carcinoma, 5.5 cm, involving submandibular gland, without morphologic evidence of pleomorphic adenoma (one tissue section per 1 cm of the tumor was examined microscopically; hematoxylin and eosin, 200×). B. Fluorescence in situ hybridization, break-apart probe, tumor cells with the rearrangement show green and red split signals in addition to the normal fused yellow signal. 81% of cells showed PLAG1 rearrangement. C–D. Salivary duct carcinoma, 3 cm, entirely submitted for microscopic examination and a 0.1 cm hyalinized nodule was identified (hematoxylin and eosin, 40×). D. 80% of cells showed HMGA2 rearrangement, fluorescence in situ hybridization, break-apart probe, tumor cells with the rearrangement show green and red split signals in addition to the normal fused yellow signal.

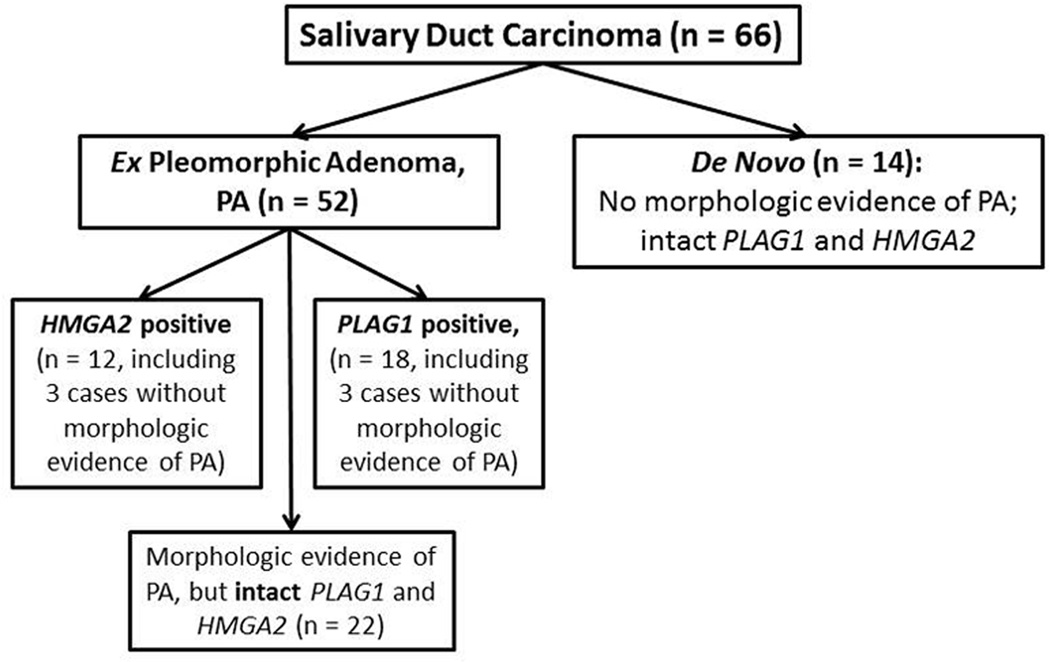

Based on the morphologic evidence of PA and PLAG1 and HMGA2 status, salivary duct carcinomas can be categorized into 4 subsets (Figure 2, including 27 cases with previously reported PLAG1 and HMGA2 alteration status7). Overall, based on morphologic appearance and PLAG1 and HMGA2 status, 78% (52/66) of salivary duct carcinoma in this study arose ex PA.

Figure 2.

Four subsets of salivary duct carcinoma: relationship between the morphologic evidence of pleomorphic adenoma and PLAG1 or HMGA2 alteration by fluorescent in situ hybridization.

The list of potential PLAG1 fusion partners includes fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1).11 Thirteen salivary duct carcinomas with PLAG1 alterations were, therefore, tested for FGFR1 rearrangement. One case with FGFR1 rearrangement was identified (case #8, Figure 3), suggesting that in this case FGFR1 is the fusion partner of PLAG1. In case #2, FGFR1 FISH failed. In the remaining 11 cases with PLAG1 alteration, FGFR1 was intact.

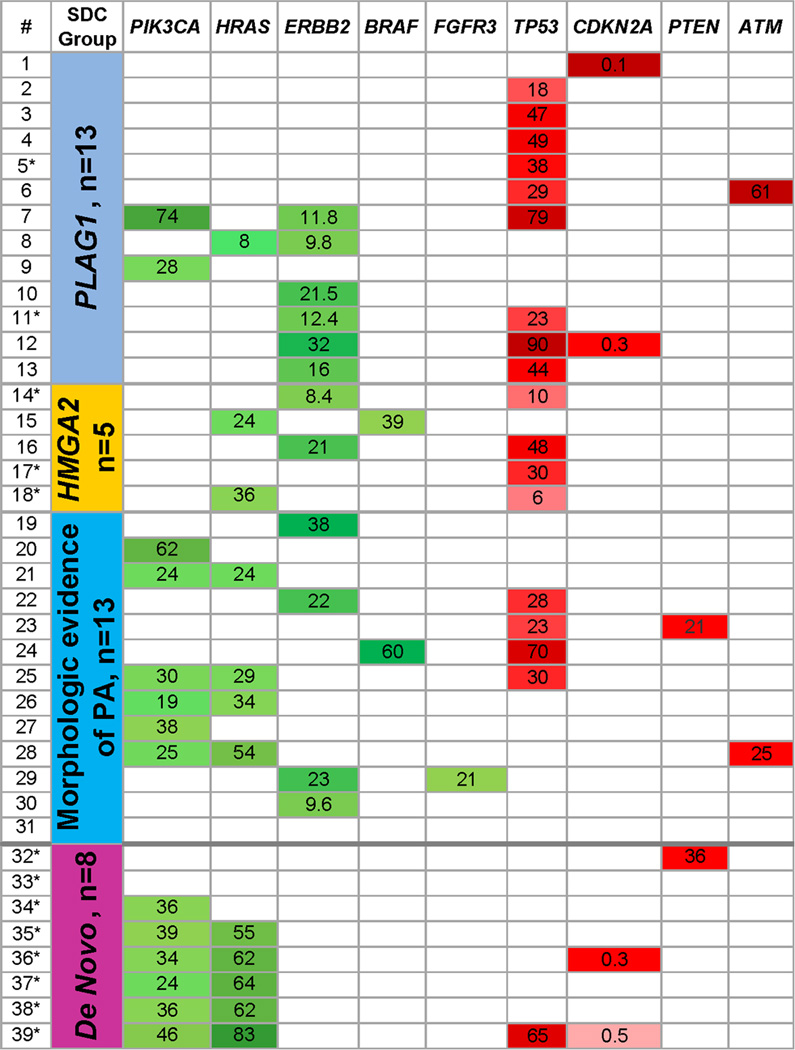

Figure 3.

The relationship between the four subsets of salivary duct carcinoma (second column) and mutations and copy number variation in 50 cancer-related genes. Only genes with mutations or copy number alterations are shown. In the first column, asterisk identifies cases without morphologic evidence of pleomorphic adenoma. Mutations and copy number gain in oncogenes are highlighted in green. Mutations and deletions in tumor suppressor genes are highlighted in red. For cases with mutations, mutant allelic frequency is shown and stronger color intensity (e.g., darker green) indicates higher mutant allele frequency. For ERBB2 and CDKN2A copy number is shown.

Patients’ disease free survival, sex, age, tumor site and size, pT, pN, and clinical stage did not correlate with the four subsets of salivary duct carcinoma.

Relationship between the four subsets of salivary duct carcinoma and genetic alterations in 50 cancer-related genes

The relationship between the four SDC subsets and mutations and copy number variation of PIK3CA, HRAS, ERBB2, BRAF, FGFR3, TP53, CDKN2A, PTEN, and ATM is shown in Figure 3.

The genes listed below were negative for mutations and copy number alterations: ABL1, AKT1, ALK, APC, CDH1, CSF1R, CTNNB1, EGFR, ERBB4, EZH2, FGFR1, FGFR2, FBXW7, FLT3, GNA11, GNAS, GNAQ, HNF1A, IDH1, IDH2, JAK2, JAK3, KDR, KIT, KRAS, MET, MLH1, MPL, NRAS, NOTCH1, NPM1, PDGFRA, PTPN11, RB1, RET, SMAD4, SMARCB1, SMO, SRC, STK11, VHL. The coverage of some hotspots for the following genes was below the laboratory cut-off of 300× reads, which is of insufficient quality to make an accurate call: TP53 (n=4), HRAS (n =1), EGFR (n = 3), APC (n =3), p16 (n =16).

TP53 mutations occurred predominantly in salivary duct carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma

TP53 mutations were the most common genetic abnormality (18/39, 46%). TP53 mutation details and the results of p53 immunohistochemistry are summarized in Supplemental Table S2. All TP53 mutations were in exons 4 through 8. TP53 mutations were more common in salivary duct carcinoma ex PA than in de novo carcinoma (17/31 vs 1/8, p = 0.033). For instance, 9 of 13 (69%) cases with PLAG1 rearrangement and 4 of 5 (80%) cases with HMGA2 rearrangement harbored TP53 mutation.

ERBB2 copy number gain occurred predominantly in salivary duct carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma

In this study, ERBB2 copy number gain was not seen in de novo salivary duct carcinoma (0/8 vs 12/31, p = 0.08; when de novo status was defined by morphology and PLAG1 and HMGA2 status). ERBB2 copy number gain was seen in salivary duct carcinoma de novo cases, when de novo status was defined by morphology alone (2/13 vs 10/26, p=0.5).

Combined HRAS/PIK3CA mutations with higher mutant allelic frequency of HRAS was seen predominantly in de novo salivary duct carcinoma

PIK3CA exon 9 (p.E542K [n = 4] and p.E545K [n = 3]) or exon 20 (p.H1047R, n = 7) mutations were identified in 14 of 39 (36%) SDCs. HRAS mutations were identified in 13 of 38 successfully tested SDC (32%), including p.Q61R (n = 8), p.Q61K (n = 2), p.G13R (n=1), p.G13V (n=1), and p.T20I (n=1). In addition to cases with isolated PIK3CA or HRAS mutation, nine cases revealed co-occurring mutations in these two genes. None of the cases with the combination of PIK3CA and HRAS mutations carried PLAG1 or HMGA2 rearrangement. Unsupervised clustering revealed that combined HRAS/PIK3CA mutations with mutant allelic frequency of HRAS higher than that of PIK3CA were seen predominantly in de novo salivary duct carcinomas (5/8 vs 2/31, p = 0.035).

Other mutations

Two cases harbored BRAF mutations: p.V600E and p.G466V (case #15, Figure 3). Two cases showed ATM mutations: p.V410A (case #6) and p.F858L (case #28). FGFR3 p.F384L mutation was identified in one case (#29).

Discussion

A variety of salivary gland carcinomas arise from pleomorphic adenoma (e.g., epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, myoepithelial carcinoma, salivary duct carcinoma). The true prevalence of malignant transformation of pleomorphic adenoma into carcinoma is best assessed by specific histologic type of salivary carcinomas. Based on morphologic evidence only, in this multi-institutional series, 70% (46/66) of salivary duct carcinomas are ex pleomorphic adenoma. This is higher than previously reported.8 This discrepancy is perhaps best explained by referral bias and a more extensive sampling of cases included in the current study: the need for abundant material and exclusion of samples with a failed next generation sequencing library may have inadvertently lead to the inclusion of more recently diagnosed cases. Over the last few years, we tended to examine salivary tumors microscopically in their entirety. This may have enriched this series for more extensively sampled cases. Anecdotally, it was previously shown that to identify pre-existing pleomorphic adenoma one might have to examine up to one hundred tissue blocks.28

When morphologic evidence of pleomorphic adenoma is complemented by the knowledge of PLAG1 and HMGA2 status, additional cases of salivary duct carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma are identified. The overall prevalence of salivary duct carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma in this series is 79% (52/66). Studying salivary duct carcinomas with molecular evidence of pleomorphic adenoma may help to fine tune our understanding of morphologic signs of pre-existing pleomorphic adenoma. For instance, prior to the knowledge of HMGA2 rearrangement in one of the cases (Figure 1C), a 0.1 cm hyalinized nodule devoid of bland ducts was not considered sufficient evidence for a pre-existing pleomorphic adenoma.

Previously, a cytogenetic study characterized basic clinicopathologic features of 220 pleomorphic adenomas with PLAG1 and HMGA2 rearrangements.10 Although technical performance of conventional cytogenetics may be distinct from that of fluorescence in situ hybridization, it is tempting to compare the age of patients with pleomorphic adenomas and salivary duct carcinomas harboring PLAG1 or HMGA2 alteration (Table 2). The reported average age of patients with PLAG1 positive pleomorphic adenoma was 39 years,10 while the average age of patients with PLAG1-positive salivary duct carcinoma in the current study was 61 years. This difference in patients’ average age suggests it may take 22 years for a PLAG1-positive pleomorphic adenoma to transform into a salivary duct carcinoma. Perhaps a better understanding of genetic alterations leading to malignant transformation of pleomorphic adenomas may lead to earlier identification of “high risk” pleomorphic adenomas.

Table 2.

Prevalence of PLAG1 or HMGA2 alteration and average age of patients with pleomorphic adenoma (literature review) and salivary duct carcinoma.

| Patients’ age, average, years (range, for patients in the current study) |

Prevalence of alterations |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pleomorphic adenoma1 |

Salivary duct carcinoma |

Pleomorphic adenoma1 |

Salivary duct carcinoma |

|

| Patients with tumors carrying PLAG1 alteration |

39 | 61 (33–75) | 25.5 % (56/220) |

26% (17/66) |

| Patients with tumors carrying HMGA2 alteration |

45.9 | 64.6 (37–81) | 13.2% (29/220) |

18% (12/66) |

The data on patients with pleomorphic adenoma are from10

The prevalence of PLAG1 and HMGA2 alterations is similar in pleomorphic adenomas and salivary duct carcinomas (Table 2), suggesting that neither PLAG1 nor HMGA2 alteration predisposes a pleomorphic adenoma to malignant transformation.

One of the technical limitations of this study is the reliance on fluorescence in situ hybridization. Fluorescence in situ hybridization is unlikely to identify intra-chromosomal rearrangements. Also, break-apart design of probes precludes identification of specific PLAG1 or HMGA2 fusion partners. For instance, the list of potential PLAG1 fusion partners includes CTNNB1 (beta-catenin), leukemia inhibitory factor receptor, transcription elongation factor A, coiled-coil-helix-coiled-coil-helix domain containing 7, and fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1).11 One case with likely PLAG1-FGFR1 fusion was identified in this study. Based on the prevalence of TP53 mutations and ERBB2 copy number gain, there may be at least two more subgroups of salivary duct carcinomas with PLAG1 rearrangement: cases with TP53 mutation only and those with TP53 mutation and ERBB2 amplification. Perhaps specific PLAG1 fusion partners (other than FGFR1) are associated with one of the above combinations of genetic abnormalities. Even when PLAG1 and HMGA2 statuses are accounted for, the genetic landscape of salivary duct carcinoma remains very complex with overlapping genetic alterations. Considering that most patients with salivary duct carcinoma present at advanced clinical stage, lack of correlation between molecular findings and disease free survival is not surprising.

ERBB2 copy number gain and TP53 were shown to be associated with malignant transformation of pleomorphic adenomas.29, 30 The findings of this study appear to reconcile some of the prior seemingly discrepant reports on the role of TP53 in malignant transformation of adenomas. TP53 abnormalities were associated with malignant transformation of pleomorphic adenomas in some31–33, but not all studies.34 Here we show that TP53 mutations are more common in salivary duct carcinomas with PLAG1 or HMGA2 alteration. It is plausible that studies that did not find an association between TP53 abnormalities and carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma inadvertently focused on carcinomas arising in pleomorphic adenomas with intact PLAG1 and HMGA2. Studies of salivary carcinomas de novo would have identified few, if any, cases with ERBB2 amplification or TP53 mutation.

One of the most distinct characteristics of de novo salivary duct carcinoma is coexisting mutations of HRAS and PIK3CA. PIK3CA is one of the most studied effectors of HRAS. For instance, HRAS/PIK3CA cooperation is crucial to HRAS-induced skin cancer formation.35, 36 In other solid tumors, PIK3CA mutations are believed to occur in invasive tumors, whereas upstream mutations in RAS genes occur at comparable rates at early and late stages, suggesting that PIK3CA mutation is a later event that may boost earlier activation of the PI3K pathway. In human mammary epithelial cells, the addition of PIK3CA p.H1047R greatly increased the anchorage-independent growth of an HRAS p.G12V mutated cell line.37 The presence of HRAS mutations at higher allelic frequency is consistent with HRAS mutation being the earlier event: the presence of mutant allele in clinical tumor samples at a frequency of more than 50% is consistent with mutant allele specific imbalance.38

Practically, the complexity of the genetic landscape of salivary duct carcinoma confounds implementation of targeted therapy. Potential therapeutic approaches are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Potential therapeutic implications of common genetic alterations in salivary duct carcinoma.

| Molecular alteration | Potential targeted therapies | References |

|---|---|---|

| Androgen receptor positivity, IHC |

Androgen deprivation therapy | 39 |

|

ERBB2 copy number gain |

ERBB2 targeting therapy (e.g., trastuzumab) | 17 |

|

ERBB2 copy number gain with co-occurring with PIK3CA, HRAS, or FGFR3 mutation |

Based on recent trials in breast carcinoma, dual targeting of ERBB2 and PIK3CA may be needed. |

40, 41 |

|

PIK3CA or HRAS mutation alone |

Mammalian target of rapamycin or mitogen- activated protein kinase/extracellular signal- regulated kinases inhibitors: everolimus, trametinib |

42, 43 |

| Combined PIK3CA and HRAS mutations |

Dual mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinases and PI3K inhibition. |

44 |

| TP53 mutations | Targeted approaches to restoring the TP53- MDM2 loop (e.g., nutlin-3 analogs). In studies of breast carcinoma, the presence of TP53 mutations was associated with better response to docetaxel chemotherapy. |

45, 46 |

| Combined TP53 and ATM alteration |

Seen in 1% of breast carcinomas, DNA- damaging chemotherapy and ATM inhibition is likely most effective in this subset of cancers |

47 |

| ATM mutation | Olaparib. Most likely ATM inhibitors are contraindicated in treatment of cancer with normal TP53 |

47, 48 |

In conclusion, the profile of mutational findings and copy number alterations vary with morphologic evidence of pleomorphic adenoma and PLAG1 or HMGA2 status. PLAG1 and HMGA2 positive cases tend to have TP53 mutations or ERBB2 copy number gain, while de novo salivary duct carcinomas frequently harbor HRAS and PIK3CA mutations. These findings elucidate the process of malignant transformation of pleomorphic adenoma into a salivary duct carcinoma and provide a list of potential predictive biomarkers for the investigation of (dual) targeted therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This project used the Head and Neck SPORE and University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute Biostatistics Facility that is supported in part by award P30CA047904.

The authors wish to thank members of the Division of the Molecular and Genomic Pathology and Developmental Laboratory of the Department of Pathology, University of Pittsburgh, for excellent technical support, and Robyn Roche for outstanding secretarial support.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Author contributions:

S.C., L.D.R.T, I.W., J.E.B., R.L.F. - conceptualization, design, acquisition of data, provision of study materials, interpretation of data, drafting the article and revising it critically, final approval of the version to be published, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. A.M.M, C.M., W.E.G. - performing experiments, development of methodology, revising the article critically, final approval of the version to be published, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. W.E.G., S.C. - drafting the article, formal analysis, methodology, drafting the article, visualization, supervision. S.C., R.L.F. – funding acquisition.

References

- 1.Delgado R, Vuitch F, Albores-Saavedra J. Salivary duct carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;72:1503–1512. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930901)72:5<1503::aid-cncr2820720503>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaehne M, Roeser K, Jaekel T, Schepers JD, Albert N, Loning T. Clinical and immunohistologic typing of salivary duct carcinoma: a report of 50 cases. Cancer. 2005;103:2526–2533. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guzzo M, Di Palma S, Grandi C, Molinari R. Salivary duct carcinoma: clinical characteristics and treatment strategies. Head Neck. 1997;19:126–133. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199703)19:2<126::aid-hed7>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams MD, Roberts D, Blumenschein GR, Jr, et al. Differential expression of hormonal and growth factor receptors in salivary duct carcinomas: biologic significance and potential role in therapeutic stratification of patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1645–1652. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3180caa099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hosal AS, Fan C, Barnes L, Myers EN. Salivary duct carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:720–725. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59980301386-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishijima T, Yamamoto H, Nakano T, et al. Dual gain of HER2 and EGFR gene copy numbers impacts the prognosis of carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma. Human pathology. 2015;46:1730–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bahrami A, Perez-Ordonez B, Dalton JD, Weinreb I. An analysis of PLAG1 and HMGA2 rearrangements in salivary duct carcinoma and examination of the role of precursor lesions. Histopathology. 2013;63:250–262. doi: 10.1111/his.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams L, Thompson LD, Seethala RR, et al. Salivary duct carcinoma: the predominance of apocrine morphology, prevalence of histologic variants, and androgen receptor expression. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2015;39:705–713. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffith CC, Thompson LD, Assaad A, et al. Salivary duct carcinoma and the concept of early carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma. Histopathology. 2014;65:854–860. doi: 10.1111/his.12454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bullerdiek J, Wobst G, Meyer-Bolte K, et al. Cytogenetic subtyping of 220 salivary gland pleomorphic adenomas: correlation to occurrence, histological subtype, and in vitro cellular behavior. Cancer genetics and cytogenetics. 1993;65:27–31. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(93)90054-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stenman G. Fusion oncogenes in salivary gland tumors: molecular and clinical consequences. Head and neck pathology. 2013;7(Suppl 1):S12–S19. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0462-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katabi N, Ghossein R, Ho A, et al. Consistent PLAG1 and HMGA2 abnormalities distinguish carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma from its de novo counterparts. Human pathology. 2015;46:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bahrami A, Dalton JD, Shivakumar B, Krane JF. PLAG1 alteration in carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: immunohistochemical and fluorescence in situ hybridization studies of 22 cases. Head and neck pathology. 2012;6:328–335. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0353-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nardi V, Sadow PM, Juric D, et al. Detection of novel actionable genetic changes in salivary duct carcinoma helps direct patient treatment. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19:480–490. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaspers HC, Verbist BM, Schoffelen R, et al. Androgen receptor-positive salivary duct carcinoma: a disease entity with promising new treatment options. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:e473–e476. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.8351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyman DM, Puzanov I, Subbiah V, et al. Vemurafenib in Multiple Nonmelanoma Cancers with BRAF V600 Mutations. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;373:726–736. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Limaye SA, Posner MR, Krane JF, et al. Trastuzumab for the treatment of salivary duct carcinoma. The oncologist. 2013;18:294–300. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffith CC, Seethala RR, Luvison A, Miller M, Chiosea SI. PIK3CA mutations and PTEN loss in salivary duct carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1201–1207. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182880d5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiosea SI, Williams L, Griffith CC, et al. Molecular characterization of apocrine salivary duct carcinoma. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2015;39:744–752. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piha-Paul SA, Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Salivary duct carcinoma: Targeting the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway by blocking mammalian target of rapamycin with temsirolimus. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:e727–e730. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edge DRB SB, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook: From the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyle DP, McArt DG, Irwin G, et al. The prognostic significance of the aberrant extremes of p53 immunophenotypes in breast cancer. Histopathology. 2014;65:340–352. doi: 10.1111/his.12398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wasserman JK, Purgina B, Lai CK, et al. Phosphaturic Mesenchymal Tumor Involving the Head and Neck: A Report of Five Cases with FGFR1 Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization Analysis. Head and neck pathology. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12105-015-0678-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roy S, Durso MB, Wald A, Nikiforov YE, Nikiforova MN. SeqReporter: automating next-generation sequencing result interpretation and reporting workflow in a clinical laboratory. The Journal of molecular diagnostics : JMD. 2014;16:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X, Jian X, Boerwinkle E. dbNSFP: a lightweight database of human nonsynonymous SNPs and their functional predictions. Human mutation. 2011;32:894–899. doi: 10.1002/humu.21517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grasso C, Butler T, Rhodes K, et al. Assessing copy number alterations in targeted, amplicon-based next-generation sequencing data. The Journal of molecular diagnostics: JMD. 2015;17:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1995:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foote FW, Jr, Frazell EL. Tumors of the major salivary glands. Cancer. 1953;6:1065–1133. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195311)6:6<1065::aid-cncr2820060602>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hashimoto K, Yamamoto H, Shiratsuchi H, et al. HER-2/neu gene amplification in carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma in relation to progression and prognosis: a chromogenic in-situ hybridization study. Histopathology. 2012;60:E131–E142. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Palma S, Skalova A, Vanieek T, Simpson RH, Starek I, Leivo I. Non-invasive (intracapsular) carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: recognition of focal carcinoma by HER-2/neu and MIB1 immunohistochemistry. Histopathology. 2005;46:144–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ihrler S, Weiler C, Hirschmann A, et al. Intraductal carcinoma is the precursor of carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma and is often associated with dysfunctional p53. Histopathology. 2007;51:362–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nordkvist A, Roijer E, Bang G, et al. Expression and mutation patterns of p53 in benign and malignant salivary gland tumors. International journal of oncology. 2000;16:477–483. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Righi PD, Li YQ, Deutsch M, et al. The role of the p53 gene in the malignant transformation of pleomorphic adenomas of the parotid gland. Anticancer research. 1994;14:2253–2257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gedlicka C, Item CB, Wogerbauer M, et al. Transformation of pleomorphic adenoma to carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland is independent of p53 mutations. Journal of surgical oncology. 2010;101:127–130. doi: 10.1002/jso.21444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta S, Ramjaun AR, Haiko P, et al. Binding of ras to phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110alpha is required for ras-driven tumorigenesis in mice. Cell. 2007;129:957–968. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castellano E, Downward J. RAS Interaction with PI3K: More Than Just Another Effector Pathway. Genes & cancer. 2011;2:261–274. doi: 10.1177/1947601911408079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oda K, Okada J, Timmerman L, et al. PIK3CA cooperates with other phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase pathway mutations to effect oncogenic transformation. Cancer research. 2008;68:8127–8136. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soh J, Okumura N, Lockwood WW, et al. Oncogene mutations, copy number gains and mutant allele specific imbalance (MASI) frequently occur together in tumor cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Locati LD, Perrone F, Cortelazzi B, et al. Clinical activity of androgen deprivation therapy in patients with metastatic/relapsed androgen receptor-positive salivary gland cancers. Head & neck. 2014 doi: 10.1002/hed.23940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Majewski IJ, Nuciforo P, Mittempergher L, et al. PIK3CA mutations are associated with decreased benefit to neoadjuvant human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-targeted therapies in breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33:1334–1339. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loibl S, von Minckwitz G, Schneeweiss A, et al. PIK3CA Mutations Are Associated With Lower Rates of Pathologic Complete Response to Anti-Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) Therapy in Primary HER2-Overexpressing Breast Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:3212–3220. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.7876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janku F, Hong DS, Fu S, et al. Assessing PIK3CA and PTEN in early-phase trials with PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors. Cell reports. 2014;6:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Infante JR, Fecher LA, Falchook GS, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and efficacy data for the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. The Lancet. Oncology. 2012;13:773–781. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70270-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mazumdar T, Byers LA, Ng PK, et al. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Biomarkers Predictive of Response to PI3K Inhibitors and of Resistance Mechanisms in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2014 doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stenman G, Persson F, Andersson MK. Diagnostic and therapeutic implications of new molecular biomarkers in salivary gland cancers. Oral oncology. 2014;50:683–690. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gluck S, Ross JS, Royce M, et al. TP53 genomics predict higher clinical and pathologic tumor response in operable early-stage breast cancer treated with docetaxel-capecitabine +/− trastuzumab. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2012;132:781–791. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1412-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang H, Reinhardt HC, Bartkova J, et al. The combined status of ATM and p53 link tumor development with therapeutic response. Genes & development. 2009;23:1895–1909. doi: 10.1101/gad.1815309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weston VJ, Oldreive CE, Skowronska A, et al. The PARP inhibitor olaparib induces significant killing of ATM-deficient lymphoid tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2010;116:4578–4587. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-265769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.