Abstract

Background

The construct of relapse is used widely in clinical research and practice of alcohol use disorder (AUD) treatment. The purpose of this study was to test the predictive validity of commonly appearing definitions of AUD relapse in the empirical literature.

Method

Secondary analyses of data from Project MATCH and COMBINE were conducted using 7 definitions of “relapse” based on drinking quantity within a single drinking episode: any drinking; at least 4/5 drinks for women/men; at least 4.3/7.1 drinks for women/men; at least 6/7 drinks for women/men; at least 6 drinks; at least 7/9 drinks for women/men; at least 8/10 drinks for women/men. Relapse was used to predict alcohol consumption, related consequences, and non-consumption outcomes (quality of life, psychosocial functioning) at end-of-treatment and up to 1 year post-treatment.

Results

Regression analyses indicated within-treatment relapse definitions significantly predicted end-of-treatment alcohol consumption and alcohol-related consequences. Heavy drinking definitions were generally more predictive than the any drinking definition, but no single heavy drinking definition was consistently a better predictor of outcomes. Relapse definitions were less predictive of longer-term alcohol-related outcomes and both shorter- and longer-term non-consumption outcomes, including health and psychosocial functioning.

Conclusions

One particular definition of relapse did not consistently stand out as the best predictor. Advances in AUD research may require reconceptualization of relapse as a multifaceted dynamic process and may consider a wider range of relevant behaviors (e.g., health and psychosocial functioning) when examining the change process in individuals with AUD.

Keywords: Alcohol Use Disorder, Relapse, Predictive Validity, Project MATCH, COMBINE

In clinical research and treatment of alcohol use disorder (AUD), the construct of “relapse” is used widely and often (Maisto et al., in press). The application of relapse to AUD advanced rapidly following the recognition of “alcoholism” as a disease by the American Medical Association (1956). However, the current (5th) edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) never defines relapse. The DSM-5 mentions relapse only twice, first in the context of noting that brain changes consequent of heavy substance use may help to explain the repeated relapses that often are observed in individuals who are diagnosed with substance use disorders (SUDs), including AUD, and second in the section on AUD development and course: “AUD has a variable clinical course that is characterized by periods of remission and relapse” (p. 493; APA, 2013).

Currently there is no standard definition of relapse, yet a number of authors have defined relapse as a recurrence of problematic alcohol use, often after a period of improvement. Others have distinguished between a “lapse” and a relapse, where a lapse is typically defined as a single instance of use, a slip, or as a discrete outcome of any use (Brownell et al., 1986; Chung and Maisto, 2006; Witkiewitz and Marlatt, 2004). Select earlier (Brownell et al., 1986; Prochaska et al., 1992) and more recent authors have defined relapse as one component of a larger, dynamic process that includes changes in alcohol consumption and other personal and social/environmental factors, such as family and vocational functioning (Hendershot et al., 2011; Kirchner et al., 2012; Shiffman, 2005; Witkiewitz and Marlatt, 2004). Behavioral change goals also have been considered in defining lapse and relapse (Brendryen et al., 2013; Hendershot et al., 2011). In summary, conceptual definitions of relapse have viewed it both as an outcome and as a part of the process of change. In each case, the focus is on a reversion to a prior undesired state, with primary attention to alcohol consumption, after some period of improvement in condition. That improved condition typically is referred to as a period of full or partial (or “early”) remission.

The construct of AUD relapse is important not only because of its widespread and frequent use, but also because of the role that it plays both in clinical practice and research. In this regard, when patients are in a period of voluntary “remission” (however defined) and return to a heavier level of drinking, clinicians often label that event a relapse (or lapse) and afford it clinically predictive value. Relapse is often seen as a need to evaluate whether the treatment in question needs modification, typically toward “more” treatment (e.g., intensity or frequency). The assumption in this context is that the occurrence of the lapse/relapse predicts poor longer-term functioning if the same level of drinking continues.

The construct of relapse in research is important for many of these same reasons. As a result, relapse has been a major topic of study among AUD clinical researchers for four decades. Unfortunately, there has been inconsistency in conceptual and empirical definitions of AUD relapse in the research literature (Hendershot et al., 2011; Maisto et al., in press). A recent systematic review of empirical studies of AUD relapse– predominantly in clinical samples –published from 2010 to 2015 identified 25 different definitions used to characterize an alcohol relapse and 7 different definitions to characterize an alcohol lapse (Maisto et al., in press). The review identified a wide range of empirical definitions with criteria for relapse varying from a single drink on one occasion to multiple days of heavy drinking over a specific time-period. Within these varied definitions, even “heavy drinking” itself was operationalized differently from study to study. The most widely used definition of a heavy drinking relapse was at least 4/5 drinks for women/men on a single occasion, which is the definition currently used by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA, 2005) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA, 2015). Unfortunately, the empirical evidence for the utility of the 4/5 heavy drinking definition, or any other definition of heavy drinking, is currently limited (Pearson et al., 2016; Patrick, 2016).

Process of Empirical Validation of the Construct of AUD Relapse

Empirical investigation of the construct of relapse is fundamentally important because of its influence on research design, measurement, and the practical interpretation of findings. As a result, the advancement of theory, research, and clinical practice may be influenced heavily by such factors as consistency and coherence in the ways that relapse has been conceptualized at the individual study level. One approach for consolidating and interpreting findings is to systematically evaluate the predictive validity of different relapse definitions for key clinical outcomes. Demonstration of the utility of any given definition of relapse first requires that an outcome criterion is selected, along with a target outcome time point. Although few empirical studies have considered alternative definitions of AUD relapse (some exceptions include Maisto et al., 2007; Ramo et al., 2012), there is precedence for this kind of research in study of the clinical course of major depressive disorder (see Frank et al., 1991; Riso et al., 1997).

The purpose of this paper was to test the predictive validity of 7 definitions of AUD relapse that have been used in published empirical studies of clinical populations. Each of these 7 definitions was tested in secondary analyses of two AUD clinical trials datasets: Combined Pharmacotherapies and Behavioral Interventions for Alcohol Dependence (COMBINE; Anton et al., 2006) and Project Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity (MATCH; Project MATCH Research Group, 1997). Each definition was tested for its occurrence during the formal treatment period. Outcomes were measured at end-of-treatment and one-year post-treatment. Associations of relapse definitions with alcohol consumption and non-alcohol consumption outcomes were tested, following current multivariate conceptions of AUD “recovery” (Kaskutas et al., 2014).

Method

Participants and Procedure

The COMBINE study (Anton et al., 2006) was a randomized clinical trial to investigate the efficacy of various combinations of psychosocial and pharmacological interventions for AUD. The psychosocial interventions included combined behavioral intervention (CBI; Miller, 2004) and medication management. The pharmacological interventions included naltrexone and acamprosate and placebo versions of these medications. Treatment was delivered over the course of 16 weeks, with the post-treatment assessment follow-up period lasting one year, except in the case of the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12; described later), which was administered at 9 months post-treatment (at 52 weeks post-baseline assessment).

Project MATCH (Project MATCH Research Group, 1997) was a randomized clinical trial that examined the relative efficacy of three different psychosocial treatments for AUD: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET), and Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF). In Project MATCH there were also two treatment arms: an outpatient arm (n = 952) and an aftercare arm (n = 774). Treatment was delivered over the course of 12 weeks with the post-treatment assessment follow-up period lasting one year after the end of treatment. Table 1 provides a summary of basic demographic information and baseline drinking-related variables among participants in COMBINE and Project MATCH. It is important to note that in both COMBINE and Project MATCH the stated primary treatment outcome goal was abstinence from alcohol.

Table 1.

Summary of Demographic and Baseline Drinking-Related Variables for COMBINE and MATCH

| COMBINE total sample (n =1383) | MATCH total sample (n =1726) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 955 (69.1) | 1307 (75.7) | ||

| Female | 428 (30.9) | 419 (24.3) | ||

| Age | 44.43 (10.19) | 40.23 (10.99) | ||

| Race | ||||

| America Indian/Alaskan Native | 18 (1.3) | 25 (1.4) | ||

| Asian | 4 (0.3) | 2 (0.1) | ||

| Black/African American | 109 (7.9) | 169 (9.8) | ||

| White | 1062 (76.8) | 1381 (80) | ||

| Hispanic | 155 (11.2) | 141 (8.2) | ||

| Multi-racial | 18 (1.3) | NA | ||

| Other | 17 (1.2) | 8 (0.5) | ||

| Non-White v. White | ||||

| White | 1062 (76.8) | 1381 (80) | ||

| Non-white | 321(23.2) | 345 (20) | ||

| Marital Status | ||||

| Not Married | 764 (55.2) | 1026 (59.5) | ||

| Married | 618 (44.7) | 698 (30.5) | ||

| ADS total | 16.70 (7.32) | 16.52 (8.01) | ||

| Baseline DDD | 12.96 (8.07) | 16.86 (11.58) | ||

| Baseline PDD | 78.59 (22.50) | 69.10 (29.96) | ||

Note. NA = not applicable. ADS = Alcohol Dependence Scale. DDD = Drinks per Drinking Day. PDD = Percentage of Drinking Days. COMBINE = Combined Pharmacotherapies and Behavioral Interventions for Alcohol Dependence. MATCH = Project Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity.

Measures

Relapse definitions

The first of these definitions was “any drinking.” This definition, also occasionally referred to as a lapse, was chosen because the Maisto et al. (in press) review found it to be the most commonly used relapse definition in prior empirical studies. The next most commonly used definition was any episode of heavy drinking, with “heavy” variously defined but most often following the NIAAA (2004, 2005) guidelines of four or more standard drinks on an occasion for adult women and five or more standard drinks on an occasion for adult men (“4/5”). The NIAAA criteria often are called “binge drinking,” and if the 4 or 5 drinks are consumed within about 2 hours, then the typical woman or man respectively will reach a blood alcohol concentration of .08%, or the legal level of intoxication in the United States. The remaining definitions were variants of this ‘any heavy drinking’ definition and all were based on number of standard drinks (using a standard drink definition of 14 grams of pure alcohol) consumed within a single occasion for women/men. The 4.3/7.1 criterion is based on the World Health Organization’s (WHO, 2000) definition of a “very high risk” drinking level. The other four definitions tested (6/7, 6 [not gender-specific], 7/9, and 8/10, respectively) have been used in studies reported in the literature (Maisto et al., in press; Pearson et al., 2016).

Participant characteristics, alcohol use, and alcohol-related consequences

In both COMBINE and MATCH, a basic questionnaire was administered to gather information on demographics (i.e., age, gender, race, marital status), the Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS; Skinner and Allen, 1982) was used to measure alcohol dependence severity at baseline, and the Form-90 (Miller, 1996) was used to measure alcohol use. The Form-90 is a calendar-based assessment for obtaining estimates of an individual’s alcohol use on a daily basis. We used data from the Form-90 to derive summary alcohol use variables for both COMBINE and MATCH. These summary alcohol use variables included percent drinking days (PDD), defined as the percentage of days during a given period of time in which an individual reported any drinking, and drinks per drinking day (DDD), defined as the average number of drinks on days that an individual reported any drinking over the course of a given period a time. We examined PDD and DDD over three key time periods, including the 30 days prior to the baseline assessment, the 30 days prior to end-of-treatment assessment (4-months/3-months post-baseline for COMBINE/MATCH), and the 30 days prior to 12-month post-treatment assessment (16-months/15-months post-baseline for COMBINE/MATCH). A 30-day assessment window was chosen because it is commonly used in AUD treatment outcome studies, and it allowed designation of end-of-treatment as one of the outcome points and yet did not overlap with the majority of the formal treatment period (90 days in MATCH and 120 days in COMBINE).

Using the Form-90 data, we also calculated 7 binary (0 = relapsed vs. 1 = did not relapse) summary alcohol use variables during the treatment period, with each variable representing a different definition of relapse. For the “any drinking” variable, participants were coded as relapsed if they reported any drinking days during the treatment period. For the “4/5” variable, participants were coded as relapsed if they reported at least one heavy drinking day (4+/5+ standard drinks for women/men). For the “4.3/7.1” variable, participants were coded as relapsed if they reported at least one day of 4.3+/7.1+ drinks for women/men. For the “6/7” variable, participants were coded as relapsed if they reported at least one day of 6+/7+ drinks for women/men. For the “6” variable, participants were coded as relapsed if they reported at least one day of 6 or more drinks, regardless of sex. For the “7/9” variable, participants were coded as relapsed if they reported at least one day of 7+/9+ drinks for women/men. For the “8/10” variable, participants were coded as relapsed if they reported at least one day of 8+/10+ drinks for women/men.

In both COMBINE and MATCH, the Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC; Miller et al., 1995) was used to measure alcohol-related consequences. The DrInC is a 50-item self-report measure that assesses the frequency with which individuals have experienced a range of different alcohol-related consequences. In both COMBINE and MATCH, we examined total DrInC scores at baseline, end-of-treatment, and 12 months post-treatment. Internal consistency reliability of the DrInC scores was excellent in both studies (α > 0.94 at all time periods).

Non-consumption outcomes

In MATCH only, the Psychosocial Functioning Inventory (PFI; Feragne et al., 1983) was used to measure psychosocial functioning. The PFI has two subscales that assess social behavior and social role performance. The social behavior scale is calculated from 10 items of the PFI and includes items that assess the frequency of engaging in problematic social behavior (e.g., “did you do things that upset your family and friends”) or experiencing problematic social interactions (e.g., “did you feel anxious or afraid with other people”), regardless of whether it occurred in the context of alcohol use. The responses to the items on the social behavior subscale were coded such that higher total scores on the social behavior subscale indicate better psychosocial functioning. The social role performance scale is calculated from 4 items of the PFI, including items assessing one’s performance in various social roles (e.g., spouse, parent, friend) and one item assessing satisfaction with leisure, social, or recreational activities. Higher scores on the social role performance subscale indicate better psychosocial functioning. Internal consistency reliability of the two subscales of the PFI was adequate (α > 0.82 at all time periods).

In COMBINE only, the SF-12 (Ware et al., 1996) was used to assess physical and mental health. The physical and mental health subscale scores of the SF-12 were scaled using T-scores with a normative mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10. The reliability of the SF-12 scales exceeded Cronbach’s α = 0.80 at all time periods.

Analysis Plan

To examine the predictive validity of the 7 relapse definitions, we conducted a series of hierarchical regression analyses in both COMBINE and MATCH. For the COMBINE study models, we used the full COMBINE sample. For the MATCH models, we conducted analyses in the full sample, the outpatient sample, and the aftercare sample. Separate regression models tested the strength of the association between each of the 7 relapse definitions and each of the clinical outcomes: PDD, DDD, drinking-related consequences, physical and mental health on the SF-12 (COMBINE only) and social behaviors and social roles on the PFI (MATCH only) at the end of treatment and up to one-year post-treatment. Each of these models first controlled for covariates including sex, age, marital status, race, total baseline alcohol dependence severity scores, baseline value of the outcome (e.g., baseline total DrInC scores included as a covariate in models with total DrInC scores as the outcome), and baseline PDD and DDD in step 1, then tested the association between each relapse definition on each outcome in step 2. The proportions of variance in each outcome accounted for by each relapse definition (R2) were estimated and the 95% CI for the R2 estimates were computed using the method described by Olkin and Finn (1995). It is important to restate that this analysis plan covered the full MATCH and COMBINE samples.

The outcome points of end-of-treatment was chosen because in clinical practice, “relapse” naturally is monitored while an individual is in treatment and its occurrence may cause a change in the treatment plan. Therefore the association between the occurrence of a relapse in this study and end-of-treatment functioning when the treatment plan essentially did not change in any prescribed or formal way is of interest. From a research perspective, heavy drinking during treatment predicts longer-term AUD treatment outcomes (e.g., Witkiewitz et al., in press). The one-year post-treatment outcome point was chosen because in AUD treatment research and practice one year post-treatment typically is when patterns of alcohol use and related variables are thought to stabilize (SAMHSA, 2006).

Results

The number of individuals who were classified in each definition and the proportion of individuals who were classified as relapsed according to a given definition who were also classified as relapsed in each of the remaining definitions are presented in Tables 2 and 3 for the COMBINE and MATCH samples, respectively. As can be seen in Tables 2 and 3, the number of individuals within each definition decreased as the level of drinking required to meet the relapse criteria increased and there was a high degree of overlap among individuals classified as “relapsed” by each definition.

Table 2.

Overlap Proportions among Relapse Definitions in COMBINE

| Any drinking | 4/5 | 4.3/7.1 | 6/7 | 6 | 7/9 | 8/10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any drinking | 1.00 | 0.836 | 0.738 | 0.691 | 0.739 | 0.582 | 0.523 |

| 4/5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.882 | 0.826 | 0.883 | 0.696 | 0.624 |

| 4.3/7.1 | 1.00 | 0.999 | 1.00 | 0.933 | 0.933 | 0.789 | 0.708 |

| 6/7 | 1.00 | 0.999 | 0.996 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.842 | 0.756 |

| 6 | 1.00 | 0.999 | 0.932 | 0.936 | 1.00 | 0.788 | 0.708 |

| 7/9 | 1.00 | 0.998 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.898 |

| 8/10 | 1.00 | 0.998 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

|

| |||||||

| N | 1092 | 913 | 806 | 755 | 807 | 636 | 571 |

Note. Proportion values in each cell are based on the number of people meeting both criteria (of the criteria listed in the corresponding row and column for a given cell), divided by the total number of people meeting the criterion listed in the row labels. For example, 100% of people meeting criteria for 4/5 also met criteria for any drinking, whereas 83.6% of people meeting criteria for any drinking also met criteria for 4/5. COMBINE = Combined Pharmacotherapies and Behavioral Interventions for Alcohol Dependence.

Table 3.

Overlap Proportions among Relapse Definitions in MATCH

| Any drinking | 4/5 | 4.3/7.1 | 6/7 | 6 | 7/9 | 8/10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any drinking | 1.00 | 0.812 | 0.697 | 0.668 | 0.685 | 0.594 | 0.558 |

| 4/5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.859 | 0.823 | 0.844 | 0.732 | 0.688 |

| 4.3/7.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.957 | 0.957 | 0.852 | 0.801 |

| 6/7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.999 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.890 | 0.836 |

| 6 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.974 | 0.975 | 1.00 | 0.867 | 0.815 |

| 7/9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.939 |

| 8/10 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

|

| |||||||

| N | 1057 | 858 | 737 | 706 | 724 | 628 | 590 |

Note. Proportion values in each cell are based on the number of people meeting both criteria (of the criteria listed in the corresponding row and column for a given cell), divided by the total number of people meeting the criterion listed in the row labels. For example, 100% of people meeting criteria for 4/5 also met criteria for any drinking, whereas 81.2% of people meeting criteria for any drinking also met criteria for 4/5. MATCH = Project Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity.

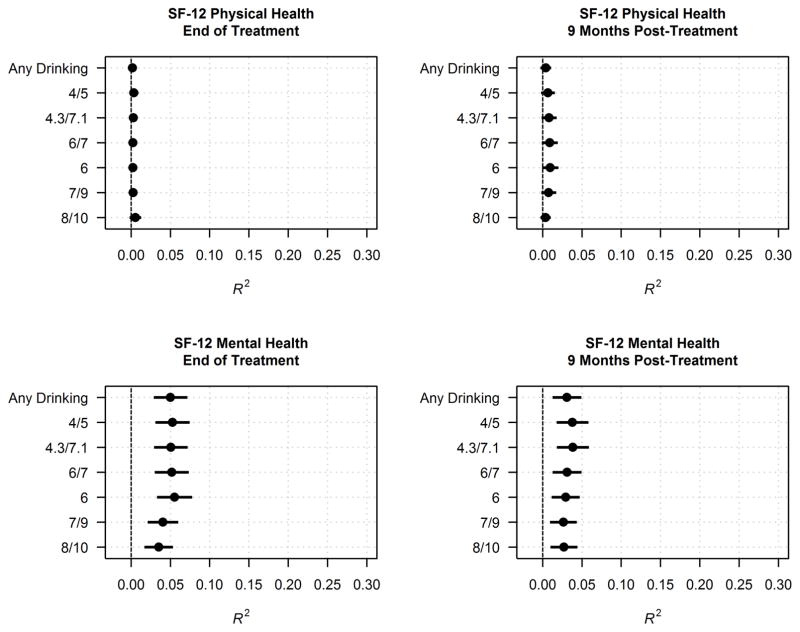

In the majority of the hierarchical regression analyses, each of the relapse classifications significantly predicted nearly all of the outcomes after controlling for covariates. The only exceptions were the models of physical health in the COMBINE study, where all of the relapse definitions explained nearly zero variance in SF-12 physical health scores.

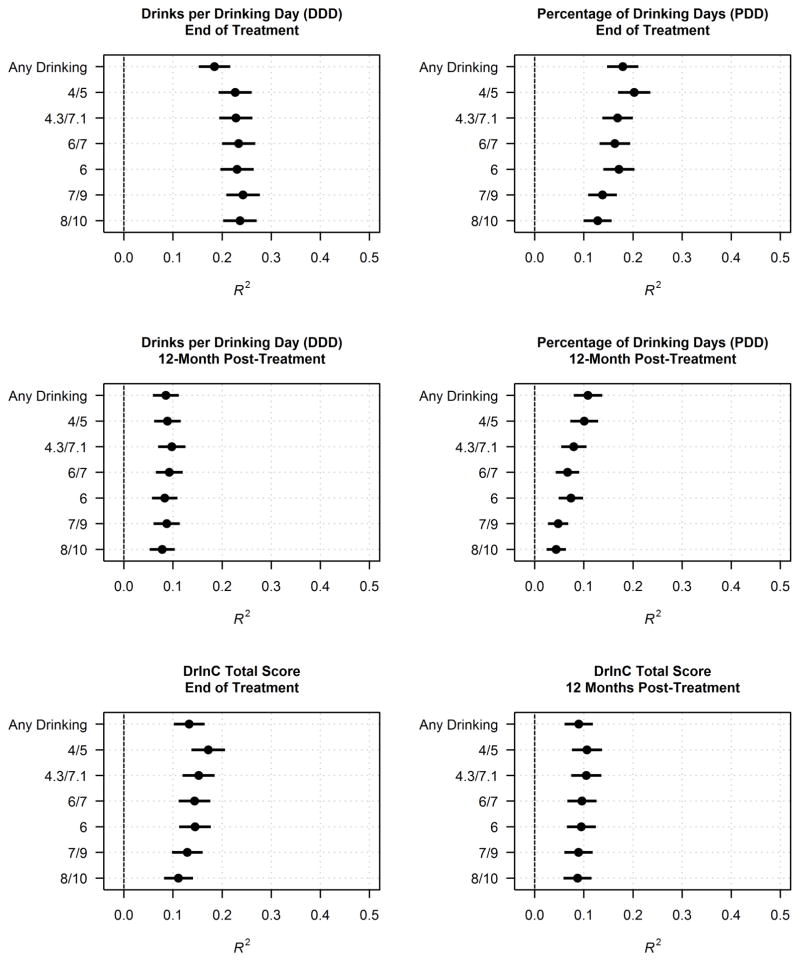

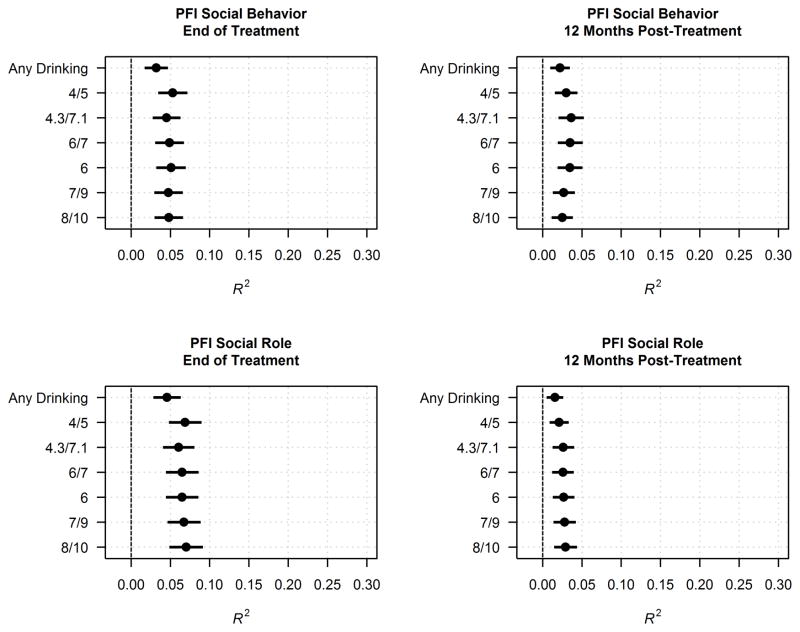

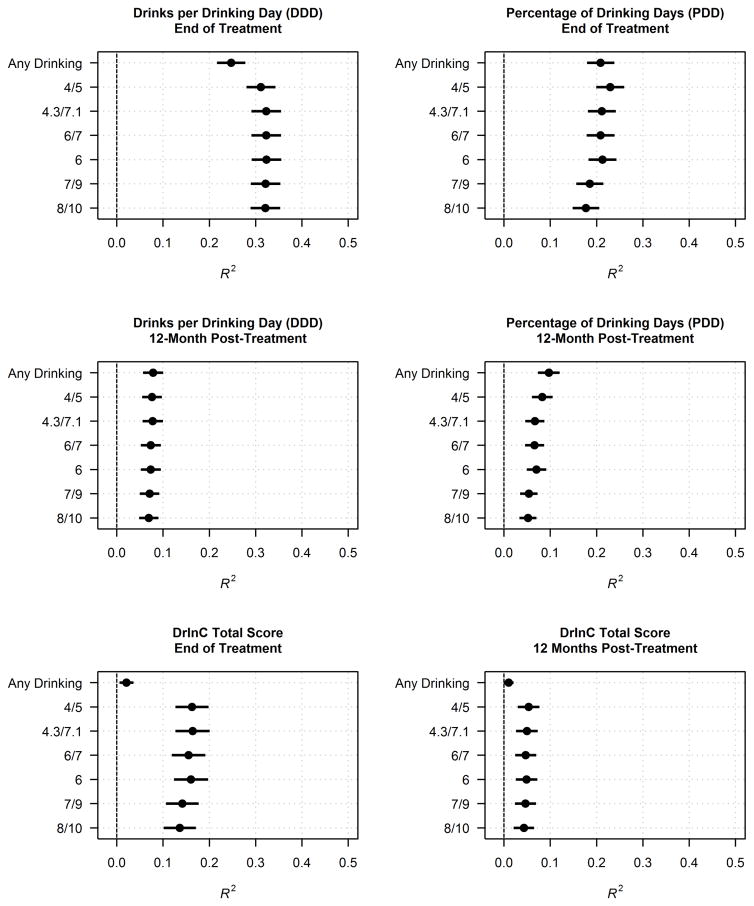

The pattern of findings did not differ substantially for the full MATCH sample, as compared to the MATCH aftercare and outpatient subsamples, thus we focused on the full sample MATCH findings. Figures 1 through 4 provide a summary of the change in R2 findings in the prediction of each outcome by the relapse definitions for the COMBINE (Figures 1–2) and MATCH samples (Figures 3–4). To put the alcohol consumption outcomes in a broader context, as shown in Table 4, among the individuals in COMBINE who were included in the relapse analyses the mean (SD) PDD/DDD at end of treatment was 34.22 (34.18)/5.91 (5.90) and was 43.62 (39.26)/6.27 (6.25) at 12 months post-treatment. The counterpart data for MATCH for the mean (SD) PDD/DDD at end of treatment was 26.39 (31.98)/7.73 (8.52) and was 32.14 (36.14)/6.64 (7.72) at 12 months post-treatment.

Figure 1.

Proportions of variance in drinking outcomes predicted by different relapse definitions (COMBINE Study). The alcohol consumption assessment interval for each outcome point was the last 30 days.

Figure 4.

Proportions of variance in non-drinking outcomes predicted by different relapse definitions (MATCH).

Figure 2.

Proportions of variance in non-drinking outcomes predicted by different relapse definitions (COMBINE).

Figure 3.

Proportions of variance in drinking outcomes predicted by different relapse definitions (MATCH). The alcohol consumption assessment interval for each outcome point was the last 30 days.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics [Mean (Standard Deviation)] for Post-Treatment Drinking Frequency and Intensity

| Among all participants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| COMBINE total sample | MATCH total sample | MATCH outpatient arm only | MATCH aftercare arm only | |

| PDD Post-Treatment | 27.34 (33.49), n = 1288 | 16.83 (28.51), n = 1657 | 19.92 (29.39), n = 923 | 12.95 (26.89), n = 734 |

| PDD 12-Months Post-Treatment | 37.37 (39.12), n = 1099 | 24.71 (34.42), n = 1573 | 27.58 (34.86), n = 871 | 21.15 (33.55), n = 702 |

| DDD Post-Treatment | 4.72 (5.78), n = 1288 | 4.93 (7.75), n = 1657 | 5.34 (7.09), n = 923 | 4.42 (8.49), n = 734 |

| DDD 12-Months Post-Treatment | 5.39 (6.25), n = 1099 | 5.18 (7.49), n = 1573 | 5.10 (6.23), n = 871 | 5.28 (8.80), n = 702 |

|

| ||||

| Among only participants who abstained entirely during the treatment period | ||||

|

| ||||

| Within COMBINE total sample | Within MATCH total sample | Within MATCH outpatient arm only | Within MATCH aftercare arm only | |

| PDD Post-Treatment | 0.00 (0.00), n = 259 | 0.00 (0.00), n = 600 | 0.00 (0.00), n = 206 | 0.00 (0.00), n = 394 |

| PDD 12-Months Post-Treatment | 14.12 (28.41), n = 233 | 11.62 (26.34), n = 577 | 12.29 (26.08), n = 197 | 11.27 (26.51), n = 380 |

| DDD Post-Treatment | 0.00 (0.00), n = 259 | 0.00 (0.00), n = 600 | 0.00 (0.00), n = 206 | 0.00 (0.00), n = 394 |

| DDD 12-Months Post-Treatment | 2.09 (4.56), n = 233 | 2.68 (6.40), n = 577 | 2.29 (4.58), n = 197 | 2.88 (7.16), n = 380 |

|

| ||||

| Among only participants who had 1 drink or more during the treatment period | ||||

|

| ||||

| Within COMBINE total sample | Within MATCH total sample | Within MATCH outpatient arm only | Within MATCH aftercare arm only | |

| PDD Post-Treatment | 34.22 (34.18), n = 1029 | 26.39 (31.98), n = 1057 | 25.65 (31.07), n = 717 | 27.95 (33.81), n = 340 |

| PDD 12-Months Post-Treatment | 43.62 (39.26), n = 866 | 32.14 (36.14), n = 982 | 31.90 (35.77), n = 667 | 32.67 (36.9), n = 315 |

| DDD Post-Treatment | 5.91 (5.90), n = 1029 | 7.73 (8.52), n = 1057 | 6.87 (7.36), n = 717 | 9.53 (10.33), n = 340 |

| DDD 12-Months Post-Treatment | 6.27 (6.35), n = 866 | 6.64 (7.72), n = 982 | 5.93 (6.43), n = 667 | 8.13 (9.75), n = 315 |

Note. PDD = Percentage of Drinking Days; DDD = Drinks Per Drinking Day.

Overall the majority of findings were consistent across COMBINE and MATCH. First, the relapse definitions explained considerably more independent variance in the alcohol consumption and alcohol-related negative consequences outcomes than in the non-consumption outcomes (SF-12 physical and mental health in COMBINE and PFI social role behavior and performance in MATCH). Second, the relapse definitions predicted end-of-treatment outcomes better than they predicted outcomes at follow-up. Third, with a few exceptions, the “any drinking” definition performed worst among the definitions, whereas there were few differences among the alternative heavy drinking definitions. Fourth, most relapse definitions tended to predict a greater proportion of variance in post-treatment DDD as compared to post-treatment PDD. Fifth, variance explained (10% or less) in 12-month DDD and PDD differed little between outcomes or among definitions.

Discussion

The results of this study show that during treatment, alcohol consumption-based definitions of relapse do reasonably well according to statistical significance and variance accounted for in predicting end-of-treatment alcohol consumption and alcohol-related consequences. This was especially the case for the various heavy drinking definitions, as compared to the any drinking definition. However, the predictive power of all relapse definitions declined considerably in predicting longer-term (one-year post-treatment outcomes) alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences and both shorter- and longer-term (9 months for the SF-12, 12 months for the PFI) non-alcohol outcomes, including health and psychosocial functioning. The findings were replicated in two independent, multi-site AUD treatment clinical trials that took place across two decades (1990s and 2000s) and involved the testing of a range of behavioral and pharmacological treatments. As a result, the sources of the data lend confidence that the findings are likely generalizable to other AUD clinical trials in the U.S.

The finding that the any drinking definition had the poorest predictive validity in considering alcohol consumption and related consequences outcomes at the end of treatment is not surprising, given that the definition requires that individuals who drink at agreed upon safe or low-risk levels still be identified as “relapsed.” In this regard, Maisto et al. (2007) showed that individuals who engage in moderate drinking (i.e., do not meet the 4/5 heavy drinking criterion for more than 5 days in the first year following treatment initiation) have outcomes at 15 months that do not differ from those of abstainers and that are significantly better than heavy drinkers. It seems reasonable that this same pattern holds within the treatment administration period (3 months or 4 months in this case) as well. There is a growing body of literature supporting the notion that low-risk drinking outcomes following alcohol treatment are similar to abstinence outcomes with respect to long-term functioning, consequences, and even health care costs following treatment (Aldridge et al., 2016; Kline-Simon et al., 2013; Witkiewitz, 2013). Such findings raise the interesting possibility that individuals who drink during or following treatment but not at what is commonly defined as a “heavy” level of consumption may be distinguished from their heavy drinking counterparts by their use of cognitive or behavioral processes of change to keep their alcohol consumption at or below some desired, non-harmful level once drinking is initiated on an occasion (Carbonari & DiClemente, 2000).

The results regarding the any drinking definition and the data summarized in Table 4 together suggest that heavier drinking during treatment likely played a major part in predicting post-treatment and one-year alcohol use, related consequences, and quality of life. This possibility warrants investigation in future research, because if confirmed it would provide an empirical basis for the clinical practice of addressing heavy drinking that occurs during AUD treatment.

The lack of appreciable differences in the predictive validity among the heavy drinking definitions likely was due to the degree of overlap in relapse status classification of individuals from one definition to the next. This result suggests that any differences in findings of studies using different heavy drinking-based single event definitions of relapse occurring during treatment may not be due primarily to such differences in definitions. The lack of differences between the various heavy drinking definitions also calls into question the unique utility and validity of the 4/5 cutoff (Pearson et al., 2016), which is widely advocated as an endpoint for clinical trials (FDA, 2015; NIAAA, 2005) and is widely used in empirical research (Maisto et al., in press).

The finding that relapse status in this study was a fairly poor predictor of psychosocial outcomes was not unexpected, given that a single event, consumption-based variable was used to predict non-consumption outcomes that likely are caused by multiple drinking- and non-drinking-related factors. Nevertheless, in clinical practice, the occurrence of a “relapse,” typically defined by consumption alone, has been given considerable weight because of its purported power to predict later alcohol consumption and other areas of functioning, such as health, social, and familial functioning, which all are incorporated in current concepts of AUD “recovery” (Kaskutas et al., 2014).

Taken together, the data suggest that single dimension, end-point definitions of relapse have restricted, shorter-term independent predictive power. The most popular end-point definitions, “any drinking” or 4/5 heavy drinking, performed worse or the same as a range of less widely used definitions. Based on these findings, we recommend future research on the development and validation of definitions of AUD relapse move beyond binary cutpoints based on alcohol consumption and treat relapse as a part of a process of AUD clinical course and change (Maisto et al., in press; Witkiewitz and Marlatt, 2004).

There are several limitations of this study that should be noted in the interpretation of its findings. The data pertain to adult individuals voluntarily enrolling in a clinical trial of AUD specialty treatment and therefore may not be representative of individuals presenting for AUD specialty treatment outside the context of a clinical trial. In addition, all of the individuals enrolled in the two clinical trials were diagnosed with DSM-IV alcohol dependence, and the relevance of the findings to individuals who would be diagnosed with DSM-IV alcohol abuse or DSM-5 AUD requires empirical verification. In addition, the concept of relapse is also relevant to individuals attempting change in their alcohol use and related behaviors without the aid of formal treatment (e.g., Prochaska et al., 1992; Witkiewitz and Marlatt, 2004), and the relevance of the current findings to those outside of treatment contexts remains unknown. Finally, the superior predictive value of the relapse definitions in predicting the end-of-treatment outcomes compared to the one-year post-treatment outcomes may have been due in part to the overlap in the relapse events (the formal treatment period, or the first 90 or 120 days following treatment initiation in MATCH and COMBINE, respectively) and end-of-treatment outcome assessment windows (last 30 days of the formal treatment period).

In conclusion, although commonly used, the within-treatment consumption-based definitions of AUD relapse tested in this study are significantly associated with short-term alcohol use outcomes but are less reliable predictors of long-term alcohol use, health, and social functioning. Moreover, one particular definition of relapse did not consistently stand out as the best predictor. Advances in AUD clinical practice and research may be facilitated if “relapse” is viewed as a multifaceted and dynamic process and if a wider range of relevant behaviors are considered when examining the change process in individuals with AUD.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by grants 2K05 AA016928, R01 AA022328, and R34 AA023304 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Contributor Information

Stephen A. Maisto, Syracuse University

Corey R. Roos, University of New Mexico

Kevin A. Hallgren, University of Washington

Dezarie Hutchison, Syracuse University.

Adam D. Wilson, University of New Mexico

Katie Witkiewitz, University of New Mexico.

References

- Aldridge A, Zarkin GA, Dowd W, Bray JW. The relationship between end of treatment alcohol use and subsequent health care costs: do heavy drinking days predict higher health care costs. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40:1122–1128. doi: 10.1111/acer.13054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association. Hospitalization of patients with alcoholism. JAMA. 1956;162:750–756. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. American Psychiatric Association; Washington: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, Gastfriend DR, Hosking JD, Johnson BA, LoCastro JS, Longabaugh R, Mason BJ, Mattson ME, Miller WR, Pettinati HM, Randall CL, Swift R, Weiss RD, Williams LD, Zweben AA. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the combine study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendryen H, Johansen A, Nesvag S, Kok G, Duckert F. Constructing a theory- and evidence-based treatment rationale for complex eHealth interventions: development of an online alcohol intervention using an intervention mapping approach. JMIR Research Protocols. 2013;2:e6. doi: 10.2196/resprot.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell KD, Marlatt GA, Lichtenstein E, Wilson GT. Understanding and preventing relapse. American Psychologist. 1986;41:765–782. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.41.7.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonari JP, DiClemente CC. Using transtheoretical model profiles to differentiate levels of alcohol abstinence success. J Consult and Clin Psychol. 2000;68:810–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Maisto SA. Relapse to alcohol and other drug use in treated adolescents: review and reconsideration of relapse as a change point in clinical course. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feragne MA, Longabaugh R, Stevenson JF. The psychosocial functioning inventory. Eval Health Prof. 1983;6:25–48. doi: 10.1177/016327878300600102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration. Alcoholism: Developing Drugs for Treatment. Food and Drug Administration; Silver Spring, MD: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, Keller MB, Kupfer DJ, Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Weissman MM. Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder: remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Archives Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:851–855. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810330075011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, Witkiewitz K, George WH, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention for addictive behaviors. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2011;6:1–17. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Borkman TJ, Laudet A, Ritter LA, Witbrodt J, Subbaraman MS, Stunz A, Bond J. Elements that define recovery: the experiential perspective. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:999–1010. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner TR, Shiffman S, Wileyto EP. Relapse dynamics during smoking cessation: recurrent abstinence violation effects and lapse-relapse progression. J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121:187–197. doi: 10.1037/a0024451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline-Simon AH, Falk DE, Litten RZ, Mertens JR, Fertig J, Ryan M, Weisner CM. Posttreatment low-risk drinking as a predictor of future drinking and problem outcomes among individuals with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(Suppl 1):E373–E380. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Clifford PR, Stout RL, Davis CM. Moderate drinking in the first year after treatment as a predictor of three-year outcomes. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:419–427. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Witkiewitz K, Hutchison D, Wilson A. Is the construct of relapse heuristic and does it advance alcohol use disorder clinical practice? J Stud Alcohol Drugs. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.849. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Form 90: A Structured Assessment Interview for Drinkingand Related Behaviors: Test Manual. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Combined Behavioral Intervention Manual: A Clinical Research Guide for Therapists Treating People with Alcohol Abuse and Dependence. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2004. COMBINE Monograph Series, Vol. 1; DHHS No. 04-5288. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An Instrument for Assessing Adverse Consequences of Alcohol Abuse. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- NIAAA. Helping Patients Who Drink too Much: A Clinician’s Guide. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 2005. NIH Publication No. 05–3769. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIAAA Council Approves Definition of Binge Drinking, NIAAA Newsletter, No. 3. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Olkin I, Finn JD. Correlations redux. Psychol Bull. 1995;118:155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME. A call for research on higher-intensity alcohol use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40:256–259. doi: 10.1111/acer.12945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MR, Kirouac M, Witkiewitz K. Questioning the validity of the 4+/5+ binge or heavy drinking criterion in college and clinical populations. Addiction. 2016 doi: 10.1111/add.13210. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Prince MA, Roesch SC, Brown SA. Variation in substance use relapse episodes among adolescents: a longitudinal investigation. J Sub Abuse Treat. 2012;43:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riso LP, Thase ME, Howland RH, Friedman ES, Simons AD, Tu XM. A prospective test of criteria for response, remission, relapse, recovery, and recurrence in depressed patients treated with cognitive behavior therapy. J Affect Disorders. 1997;43:131–142. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(96)01420-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Dynamic influences on smoking relapse process. J Pers. 2005;73:1715–1748. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Allen BA. Alcohol dependence syndrome: measurement and validation. J Abnorm Psych. 1982;91:199–209. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.91.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Substance abuse: Clinical issues in intensive outpatient treatment (TIP 47) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K. “Success” following alcohol treatment: moving beyond abstinence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(Suppl 1):E9–E13. doi: 10.1111/acer.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems: that was Zen, this is Tao. American Psychologist. 2004;59:224–235. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.4.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Roos CR, Pearson MR, Hallgren KA, Kirouac M, Forechimes A, Wilson AD, Robinson CS, McCallion E, Tonigan JS, Heather N, Maisto SA. How much is too much? Patterns of drinking during alcohol treatment and associations with post-treatment outcomes across three alcohol clinical trials. J Stud Alc Drugs. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.59. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) International Guide for Monitoring Alcohol Consumption and Related Harm. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2000. [Google Scholar]