Abstract

Background

More than half of the hospitalized older adults discharged to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) have more than three geriatric syndromes. Pharmacotherapy may be contributing to geriatric syndromes in this population.

Objectives

Develop a list of medications associated with geriatric syndromes and describe their prevalence in patients discharged from acute care to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs)

Design

Literature review and multidisciplinary expert panel discussion, followed by cross-sectional analysis.

Setting

Academic Medical Center in the United States

Participants

154 hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries discharged to SNFs

Measurements

Development of a list of medications that are associated with six geriatric syndromes. Prevalence of the medications associated with geriatric syndromes was examined in the hospital discharge sample.

Results

A list of 513 medications was developed as potentially contributing to 6 geriatric syndromes: cognitive impairment, delirium, falls, reduced appetite or weight loss, urinary incontinence, and depression. Medications included 18 categories. Antiepileptics were associated with all syndromes while antipsychotics, antidepressants, antiparkinsonism and opioid agonists were associated with 5 geriatric syndromes. In the prevalence sample, patients were discharged to SNFs with an overall average of 14.0 (±4.7) medications, including an average of 5.9 (±2.2) medications that could contribute to geriatric syndromes, with falls having the most associated medications at discharge, 5.5 (±2.2).

Conclusions

Many commonly prescribed medications are associated with geriatric syndromes. Over 40% of all medications ordered upon discharge to SNFs were associated with geriatric syndromes and could be contributing to the high prevalence of geriatric syndromes experienced by this population.

Keywords: medications, geriatric syndromes, polypharmacy, potentially inappropriate medications, skilled nursing facility, older adults, elderly, adverse drug events

INTRODUCTION

Geriatric syndromes are common clinical conditions in older adults that do not fall into specific disease categories. Unlike the traditional definition of a “syndrome”, geriatric syndrome refers to a condition that is mediated by multiple shared underlying risk factors.1,2 Conditions commonly referred to as geriatric syndromes include delirium, cognitive impairment, falls, unintentional weight loss, depressive symptoms and incontinence. Even though many perceive it as “medical misnomer”,3 geriatric syndromes have been shown to negatively impact quality of life and activities of daily living in older adults.2 They are also associated with adverse outcomes such as increased healthcare utilization, functional decline and mortality, even after adjusting for age and disease severity.4–6 Hospitalized older adults, including those discharged to skilled nursing facilities7,8 are particularly at high risk for new-onset or exacerbation of geriatric syndromes and poor outcomes.7,9,10 However, hospital providers seldom assess, manage, or document geriatric syndromes because they are often overshadowed by disease conditions that lead to an acute episode requiring hospitalization (e.g., heart disease).11

Pharmacotherapy is the cornerstone of hospital treatment and it is well-known that it affects multiple physiologic systems causing “side-effects” apart from the condition they are approved to treat. Given that geriatric syndromes are a result of impairments in multiple organ systems, it is plausible that pharmacotherapy may initiate or worsen these syndromes.12 Medication-related problems in older adults are well known. Polypharmacy and adverse drug events (as a result of drug-drug/disease interactions and changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics) are prevalent in multimorbid elderly patients.13–16 The prescribing cascade17 increases the medication burden and may be a contributing factor for geriatric syndromes in hospitalized patients.18 For instance, laxatives may be prescribed to counteract constipation caused by anticholinergic drugs.

The American Geriatric Society (AGS) Beers list19,20 and similar criteria21 provide excellent resources to identify medications with potentially harmful interactions or adverse effects in older adults. Although these lists include medicines associated with a specific geriatric syndrome, they were not developed to explicitly link medicines across multiple geriatric syndromes, regardless of indication or appropriateness. For example, medications that effect important geriatric syndromes like unintentional weight/appetite loss, depression and urinary incontinence are not extensively covered. In addition, disease-appropriate medications (e.g. beta blockers for systolic heart failure), that may be associated with a geriatric syndrome (e.g. falls) are not included; however, they may be important to consider for a patient and clinician that are weighing the disease benefits compared to the geriatric syndrome-related risks. Finally, the AGS 2015 Beers criteria panel mentions the limitation that many medication associations may be excluded since older adults are less represented in clinical trials.20 Clinicians are currently limited in identifying medications potentially contributing to a broad set of geriatric syndromes in their patients without a specific list of medications associated with geriatric syndromes (MAGS).20

In response to this gap, identifying these medications is important and should be a starting point in efforts toward prevention and treatment of geriatric syndromes. The two main objectives of this study were to first identify medications that may meaningfully contribute to six geriatric syndromes and subsequently describe the frequency of these medications in a population transitioning from acute care to post-acute care to highlight the need and potential impact of such a list.

METHODS

This study included two phases that aligned with our two primary objectives. Phase one involved identifying medications associated with six geriatric syndromes and Phase two included a cross-sectional analysis of the prevalence of these medications in a sample of patients discharged to SNFs.

Phase One: Development of Medications Associated with Geriatric Syndromes (MAGS) List

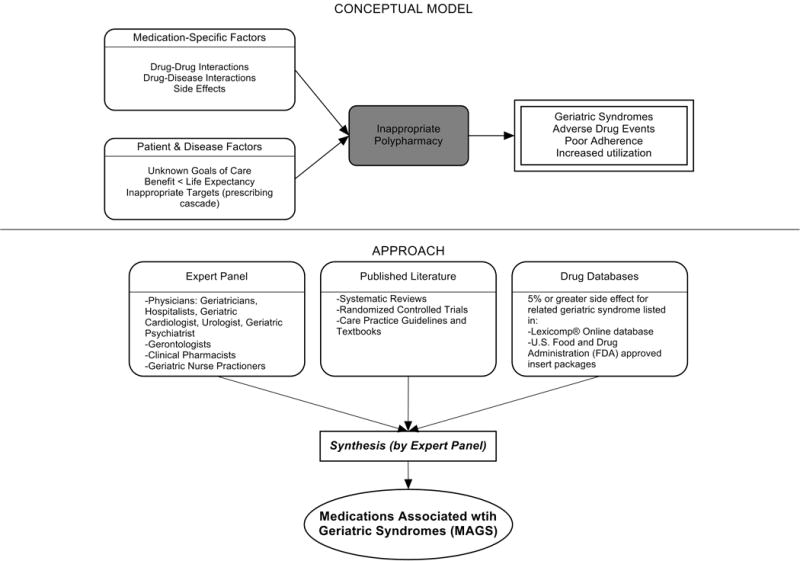

Figure 1 depicts the underlying conceptual model and approach that was used in Phase 1. The interaction between the patient factors and medication leads to polypharmacy that contributes to geriatric syndromes and additional adverse outcomes. As a starting point for mitigating geriatric syndromes, we used an iterative analytical process to identify a list of medications associated with the following geriatric syndromes that were documented to be highly prevalent in patients discharged to SNFs: cognitive impairment, delirium, falls, unintentional weight and/or appetite loss, urinary incontinence and depression.8 In order to be inclusive and sensitive, our approach differed from traditional systematic reviews, and in fact was meant to bring together much of the established systematic literature about disparate geriatric syndromes in one place since patients often do not experience a geriatric syndrome in isolation, but rather experience multiple geriatric syndromes.8 The MAGS list had three main inclusion criteria (See Figure 1) - (1) evidence in the published literature (systematic reviews, cohort studies, randomized clinical trials) that the medication is related to the syndrome (2) expert panel opinion (3) drug databases (Lexicomp Online® database22 and/or U.S Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved package inserts).23 We generated an initial list of medications based on these three main criteria to identify medications with significant associations to each geriatric syndrome. The list was further expanded and vetted using an iterative review of each medication list as it related to each geriatric syndrome through a series of group meetings focused around each geriatric syndrome. Following further discussion, we obtained agreement among all team members for medications included in the final list. For each geriatric syndrome, we excluded medications from consideration if it was used to treat the same geriatric syndrome (e.g., alpha adrenergic blockers used to treat incontinence in men were listed as associated with incontinence only in women). We classified medications according to the Established Pharmacologic Class available at the FDA website. We also compared our final MAGS list with the 2015 AGS Beer’s list20 by identifying medications that were related to the six geriatric syndromes. This included Beers20 cited rationale of anticholinergic, extrapyramidal symptoms, orthostatic hypotension (e.g., falls), high risk adverse central nervous system effects, sedating, cognitive decline (e.g., antipsychotics), delirium, falls, fractures, incontinence and gastrointestinal (e.g., nausea, vomiting). Specifically, we assessed whether the medications were included as inappropriate by the AGS Beers 201520 list and also whether they documented the syndrome association for that medication.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model and Approach for Development of the Medication Associated with Geriatric Syndromes (MAGS) List (Phase 1)

Phase 2: Prevalence of MAGS in hospitalized older adults discharged to SNFs

Sample

We next applied the MAGS list to a convenience sample of hospitalized patients discharged to SNFs in order to assess the prevalence of MAGS in this sample, and also to compare with the prevalence of Beers criteria20 medications. Our sample was selected from data collected as part of a quality improvement project to reduce hospital readmissions in patients discharged to SNF. The larger study enrolled a total 1093 medical and surgical patients who had Medicare insurance eligibility and were discharged from one large university hospital to 23 area SNFs from January 17, 2013 through July 31, 2014. The university Institutional Review Board waived the requirement for written consent. For the purpose of this sub-study we selected the first 154 patients with complete chart abstraction (approximately 15% of the total) as a convenience sample.

Data Analysis

We applied descriptive statistics to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics of the convenience sample. In order to understand potential selection biases that could have been resulted by the convenience sampling, we compared participant characteristics of the convenience sample (N=154) with the characteristics of the remaining participants of the larger study (N=939) using independent sample t-tests and chi-square tests for continuous and categorical measures, respectively. We applied the MAGS list and the AGS 2015 Beers criteria20 for the sample of 154 and identified the medications associated with each of the six geriatric syndromes from the discharge medication lists completed by hospital clinical pharmacists. For each patient, we identified both scheduled and PRN (pro re nata, or as needed) medications associated with each geriatric syndrome. Thereafter, we determined whether the discharge list contained at least one medication associated with geriatric syndrome as per the MAGS list and the AGS Beers 2015 criteria20 and the percentage of overall medications that were part of the MAGS and Beers lists. Data were aggregated using means and standard deviations (SD) across syndromes (i.e., number of discharge medications per syndrome per patient) along with the percentage of patients with one or more medication related to a specific syndrome and the percentage of medications that were MAGS. All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistical Package (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0).

RESULTS

Phase 1: Medications Associated with Geriatric Syndromes (MAGS) List

The iterative process applied in this analysis generated a list of 513 medications associated with the six geriatric syndromes. The list of medications related to each syndrome and the corresponding rationale and relevant references for their inclusion is presented in Appendix 1. Table 1 summarizes these medications across 18 major drug categories. Antiepileptics were linked to all six geriatric syndromes while antipsychotics, antidepressants, antiparkinsonism and opioid agonists were associated with five syndromes. Ten of the 18 categories were associated with three geriatric syndromes – cognitive impairment, delirium and falls. Four medication categories were associated with only one syndrome. Non-opioid/non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and/or analgesics and non-opioid cough suppressant and expectorant medications were associated with falls syndrome only. Hormone replacement medications were associated with depression only and immunosuppressants were associated with unintentional weight and appetite loss only.

Table 1.

Summary of Medications Associated with Geriatric Syndromes (MAGS)

| Major Medication Category | Delirium | Cognitive Impairment | Falls | Unintentional Weight and appetite loss | Urinary Incontinence | Depression | Drug class/Drug within each category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotics | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Atypical and Typical Antipsychotics, Buspirone | ||

| Antidepressants | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Tricyclic and Tetracyclic Antidepressants, Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors, Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor, Aminoketone | |

| Antiepileptics | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Antiepileptics, Mood stabilizers, Barbiturates |

| Antiparkinsonism | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Aromatic Amino Acid Decarboxylation Inhibitor & Catechol-O-Methyltransferase Inhibitor, Catecholamine-depleting Sympatholytic, Catechol-O-Methyltransferase Inhibitor, Dopaminergic Agonist, Ergot derivative, Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor, Nonergot Dopamine Agonist, | |

| Benzodiazapines | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Benzodiazapines only | |||

| Non-Benzodiazepine Hypnotics | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Benzodiazepine Analogs, Non-benzodiazepine Hypnotics, Tranquilizers, Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid A Receptor Agonist | |||

| Opioid agonists | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Full or Partial Opioid Agonists, Opiates, Opioids | |

| Non-Opioid/Non-Steroidal Anti inflammatory and/or Analgesics | ✓ | Non -Opioid Analgesics, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), COX-2 selective inhibitor NSAIDs | |||||

| Antihypertensives | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Calcium Channel Blocker, Beta Adrenergic Blocker, Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor, Angiotensin 2 Receptor Blocker, Alpha Adrenergic Blocker, Diuretics (Loop, Potassium sparing, Thiazide), Nitrate Vasoldilators, Aldosterone blocker | |||

| Antiarrhythmic | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Antiarrhythmics, Cardiac Glycosides | |||

| Antidiabetics | ✓ | ✓ | Insulin and Insulin Analogs, Sulfonylureas, Alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitor, Amylin Analog, Biguanide, Glinide, GLP-1 Receptor Agonist, Glucagon-like peptide-1 agonist | ||||

| Anticholinergics and/or Antihistaminics | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Anticholinergics, Histamine Receptor Antagonists, Muscarininc Antagonists, Combined Anticholinergics and Histamine Receptor Antagonists | ||

| Antiemetics | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Antiemetics, Dopaminergic Antagonists, Dopamine-2 Receptor Antagonist | |||

| Hormone Replacement | ✓ | Corticosteroids, Progestin, Estrogen, Estrogen Agonist/Antagonist, Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone Receptor Agonist | |||||

| Muscle Relaxers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Muscle Relaxers | ||

| Immunosuppressants | ✓ | Calcineurin Inhibitor Immunosuppressant, Folate Analog metabolic Inhibitor, Purine Antimetabolite | |||||

| Non-Opioid Cough Suppressants & Expectorants | ✓ | Expectorant, Non-narcotic Antitussive, Sigma-1 Agonist, Uncompetitive N-methyl-D-aspartate Receptor Antagonist | |||||

| Antimicrobiasl | ✓ | ✓ | Macrolide, Cephalosporin, Penicillin class, Rifamycin, Non-Nucleoside Analog Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor, Influenza A M2 Protein Inhibitor | ||||

| Others | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Beta3-Adrenergic Agonist, Methylxanthine, Cholinesterase Inhibitor, Interferon Alpha and Beta, Partial Cholinergic Nicotinic Agonist, Tyrosine Hydroxylase, Retinoid, Serotonin-1b and Serotonin-1d Receptor Agonist, Stimulant Laxative, Vitamin K Antagonist, Platelet Aggregation Inhibitor |

Associated syndrome checked if at least two or more medications within the wider class are associated with the syndrome

Approximately 58% of the medications overlapped with the AGS 2015 Beer’s Criteria20 irrespective of whether the specific syndrome association was stated in the rationale.20 Medications that overlapped were mostly in the delirium, cognitive impairment and falls category with only a few overlaps in depression, unintentional weight loss and urinary incontinence lists (see Appendix 1).

Phase 2: Prevalence of Medications Associated with Geriatric Syndromes

Amongst 154 participants the mean age was 76.5 (±10.6) years, 64.3% were female, 77.9% were White and 96.1% non-Hispanic. The median hospital length of stay was six days with an interquartile range of five days. The orthopedic service discharged the highest proportion of patients (24%) followed by the geriatrics and internal medicine services, which each discharged 19.5% of the patients (Table 2). The remaining participants of the larger quality improvement project (N=939) did not significantly differ on these demographic and clinical characteristics except for hospital length of stay, which was shorter in the sample analyzed (Appendix 2).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics for a Sample of 154 Medicare Insurance Eligible Patients Discharged to Skilled Nursing Facilities.

| N=154 | |

|---|---|

| Baseline Characteristics | Mean (±SD)or Percent (n) |

| Age, years | 76.5 (±10.6) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 64.3% (99) |

| Race | |

| White | 77.9% (126) |

| Black | 16.2% (25) |

| Unknown | 0.6% (1) |

| Declined | 0.6% (1) |

| Missing | 0.6% (1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 96.1% (148) |

| Hispanic | 1.3% (2) |

| Unknown | 2.6% (4) |

| Hospital Length of Stay, days | 7.0 (±4.2) |

| Hospital Length of Stay, days, Median (IQR) | 6.0 (5.0) |

| Number of Hospital Discharge Medications, count | 14.0 (±4.7) |

| Discharge Service | |

| Orthopedic Service | 24.0% (37) |

| Geriatric Service | 19.5% (30) |

| Internal Medicine | 19.5% (30) |

| Other | 37.0% (57) |

Patients were discharged to SNFs with an average of 14.0 (±4.7) medication orders. Overall, 43% (±13%) of these discharge medication orders were MAGS. Every patient in the sample was ordered at least one medication associated with geriatric syndromes. Multiple MAGS were the norm, with an average of 5.9 (±2.2) MAGS per patient. Multiple associated geriatric syndromes were also the norm, as 98.1% of the sample had medication orders associated with at least two different syndromes.

When the Beer’s criteria20 were applied to the medication orders (instead of the MAGS list), problematic medications appeared less common. Patients had an average of 3.04 (± 1.7) MAGS that were also listed on the AGS 2015 Beer’s list,20 representing an average of 22.3% of all discharge orders.

Table 3 illustrates the average number of medications per patient associated with each syndrome and the percentage of patients (number in parentheses) discharged with at least one medication associated with each syndrome per the MAGS list and the Beers 2015 criteria.20 For example, per the MAGS list, the syndrome most frequently associated with medications was falls with patients discharged on an average of 5.5 (±2.2) medications associated with falls and 100% of the sample discharged had at least one discharge medication associated with falls. Alternatively, the syndrome associated with the lowest frequency of medications was unintentional weight loss (with an average of 0.38 medications per patient), although 36% of these patients had more than one discharge medication associated with weight loss. As seen in Table 3, the mean and prevalence of one or more medications associated with each of the geriatric syndromes as identified by the Beers 2015 criteria20 was lower than the ones identified by the MAGS list developed for this study.

Table 3.

Prevalence of Medications Associated with Geriatric Syndromes per MAGS and AGS Beers 2015 criteria in an Older Cohort of Hospitalized Patients Discharged to Skilled Nursing Facilities (N=154)

| Associated Medications per MAGS list | Associated Medications per AGS Beers 2015 criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geriatric Syndromes | Mean ± SD | Percentage of patients receiving ≥ 1 related medication | Mean ± SD | Percentage of patients receiving ≥ 1 related medication |

| Cognitive Impairment | 1.8 (±1.2) | 84.4% (130) | 1.6 (±1.2) | 78.6% (121) |

| Delirium | 1.4 (±1.1) | 76.0% (117) | 1.3 (±1.2) | 68.2% (105) |

| Falls | 5.5 (±2.2) | 100% (154) | 2.6 (±1.6) | 92.2% (142) |

| Unintentional Weight and/or Appetite Loss | 0.4 (±0.5) | 36.3% (56) | 0.1 (±0.3) | 6.5% (10) |

| Urinary Incontinence | 1.6 (±1.0) | 85.7% (132) | 0.1 (±0.2) | 5.8% (9) |

| Depression | 1.7 (±1.0) | 90.9% (140) | 0.0 (±0.0) | 0.0% (0) |

| All syndromes | 5.9 (±2.2) | 100% (154) | 3.0 (±1.7) | 95% (149) |

DISCUSSION

An iterative process of evidence review by a multidisciplinary panel resulted in a list of 513 medications associated with six common geriatric syndromes. This analysis demonstrated that hospitalized, older patients discharged to SNFs were frequently prescribed MAGS. The rate of prescribing ranged from 100% of patients with a medication associated with falls to 36% for unintentional weight loss. Moreover, an alarming 43% of all medications at hospital discharge were MAGS. For this vulnerable population, the combination of high prevalence of MAGS and high risk of geriatric syndromes emphasize a need to critically review the risks and benefits of MAGS throughout hospitalization and at the time of discharge.

A body of evidence demonstrates that many drugs in a typical older adult regimen have no specific clinical indication, are considered inappropriate, or have uncertain efficacy in the geriatric population.24–26 This study builds on the foundational work described in landmark reviews such as the AGS Beers20 and STOPP/START21 criteria. Both of these tools, however, were specifically designed as screening tools to identify medications considered unsafe for older adults under most circumstances and within specific illness states.19–21 They are most often utilized when starting a medication to avoid acute adverse events. In contrast, the MAGS list was developed to be inclusive of medications that are often appropriate for many medical diagnoses but may also contribute to underlying geriatric syndromes that are more chronic in nature. In addition to the other tools, inclusion of such medicines increases the sensitivity of screening for medications that can be targeted through patient-centered deprescribing efforts when clinically appropriate.

A major strength of this study is that we bring together evidence across a spectrum of geriatric syndromes commonly experienced by hospitalized elders. In addition to evaluating multiple syndromes, we applied multiple modalities; particularly the use of an iterative review process by a multidisciplinary team of experts and using Lexicomp® and FDA insert packages for linking medications to specific geriatric conditions. The inclusion criteria were broadened beyond single sources of evidence in an effort to capture a comprehensive list of medications. As a result, the MAGS list can be implemented as a screening tool for deprescribing interventions and assessing medication appropriateness to address individual or clusters of geriatric syndromes within a patient.

In addition to expanding this knowledge base, clinical relevance of the MAGS list is highlighted by the its application to a sample of hospitalized older adults discharged to SNFs, a cohort known to experience geriatric syndromes. In fact, 43% of patients’ medications at hospital discharge were MAGS. Importantly, due to the cross-sectional nature of this study we cannot be certain if the medication caused or potentiated each of the geriatric syndromes. However, hospitals and SNFs are devoting major resources toward reduction of falls, avoidance of urinary catheter use, and reduction of preventable readmissions. These efforts can be complemented by considering the number of medications associated with falls, urinary incontinence and overall MAGS burden. The striking prevalence of MAGS demonstrates a rigorous need to weigh the risks and benefits of these medications. Above all, the intent of this study is not to propose that any MAGS be reflexively stopped, but rather that the MAGS list should facilitate a holistic approach to care for the complex older adult. For example, standard therapies such as gabapentin may be appropriate for treating neuralgic pain but may also contribute to falls and urinary incontinence. Thus, alternative pain treatments could be selected in place of gabapentin for a 75-year old patient who is experiencing recurrent falls and increasing incontinence. Therefore, the MAGS list enables a patient-provider discussion wherein medications’ therapeutic benefits can be weighed against risks posed by specific clusters of geriatric syndromes, potential impact on quality of life and consistency with goals of care.

This study has some limitations. First, although we examined a broad number of geriatric syndromes, several other geriatric syndromes experienced by hospitalized older adults were not addressed including: fecal incontinence, insomnia and functional impairment. These syndromes were intentionally excluded from the study a priori due to reasons of feasibility and scope. Second, unlike the Beer’s 2015 criteria, the MAGS list does not sub-classify associations of medications with geriatric syndromes for patients with specific diseases (e.g., heart failure). In fact, our MAGS list included medications often indicated in treating these diagnoses. A clinician must work with the patient to weigh the disease-specific benefits of some medications with the potential effect on geriatric syndrome symptoms and outcomes. Third, the instrument has a very high sensitivity which was intended to generate an inclusive list of medications that enable providers to weigh risks of geriatric syndromes with the intended indication benefit. The objective is not to use this list as a reflexive tool but rather help clinicians identify a starting point to address geriatric syndromes in their patients to make patient-centered medication decisions. Although the MAGS list is intentionally large (sensitive), the advent of advanced bioinformatics can enable MAGS to be assessed in the future for both clinical and research purposes. Fourth, FDA insert packages and Lexicomp® databases report anything experienced by the patient whilst on the particular medication but it might not necessarily imply a causative link. The high use of MAGS and the specific geriatric syndrome may co-exist due to the high prevalence and interplay of multimorbidity, polypharmacy and geriatric syndromes in this population. Lastly, the list was developed by expert panel members predominantly from a single institution which may introduce bias. Despite these limitations, the prevalence of these medications in a sample of patients transitioning from acute to post-acute care highlights the utility of the MAGS list in future clinical research and quality improvement endeavors.

In conclusion, the MAGS list provides a comprehensive and sensitive indicator of medications associated with any of six geriatric syndromes regardless of medication indication and appropriateness. The MAGS list provides an overall degree of medication burden with respect to geriatric syndromes and a foundation for future research to assess the relationship between the presence of geriatric syndromes and syndrome-associated medications. The MAGS list is an important first step in summarizing the data that link medications to geriatric syndromes. Future studies are needed to broaden the analysis of MAGS for other common geriatric syndromes and to identify new and emerging medications not present during the time of this analysis. MAGS lists have the potential to facilitate deprescribing efforts needed to combat the growing epidemic of overprescribing that may be contributing to the growing burden of geriatric syndromes among older patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Linda Beuscher, Dr. Patricia Blair Miller, Dr. Joseph Ouslander, Dr. William Stuart Reynolds and Dr. Warren Taylor for providing their expertise and participating in the expert panel discussions that facilitated the development of the MAGS list. We would also like to recognize the research support provided by Christopher Simon Coelho.

Funding Sources

This research was supported by the Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services grant #1C1CMS331006 awarded to Principal Investigator, John F. Schnelle, PhD. Dr. Vasilevskis was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health award K23AG040157 and the Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC). Dr. Bell was supported by NIA - K award K23AG048347-01A1. Dr. Mixon is supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award (12-168). This research was also supported by CTSA award UL1TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies, the National Center for Advancing Translation Science, the National Institutes of Health or the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Each co-author contributed significantly to the manuscript. Dr. Kripalani has received stock/stock options from Bioscape Digital, LLC. None of the other authors have significant conflicts of interest to report related to this project or the results reported within this manuscript.

References

- 1.Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tinetti ME, Inouye SK, Gill TM, Doucette JT. Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence. Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes. JAMA. 1995;273:1348–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olde Rikkert MG, Rigaud AS, van Hoeyweghen RJ, de Graaf J. Geriatric syndromes: medical misnomer or progress in geriatrics? Neth J Med. 2003;61:83–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buurman BM, Hoogerduijn JG, de Haan RJ, et al. Geriatric conditions in acutely hospitalized older patients: prevalence and one-year survival and functional decline. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang HH, Sheu JT, Shyu YI, Chang HY, Li CL. Geriatric conditions as predictors of increased number of hospital admissions and hospital bed days over one year: findings of a nationwide cohort of older adults from Taiwan. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59:169–74. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cigolle CT, Langa KM, Kabeto MU, Tian Z, Blaum CS. Geriatric conditions and disability: the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:156–64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-3-200708070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lakhan P, Jones M, Wilson A, Courtney M, Hirdes J, Gray LC. A prospective cohort study of geriatric syndromes among older medical patients admitted to acute care hospitals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2001–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell SP, Vasilevskis EE, Saraf AA, et al. Geriatric Syndromes in Hospitalized Older Adults Discharged to Skilled Nursing Facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016 doi: 10.1111/jgs.14035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen LA, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, et al. Discharge to a skilled nursing facility and subsequent clinical outcomes among older patients hospitalized for heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:293–300. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.959171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:219–23. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flood KL, Rohlfing A, Le CV, Carr DB, Rich MW. Geriatric syndromes in elderly patients admitted to an inpatient cardiology ward. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:394–400. doi: 10.1002/jhm.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lund BC, Schroeder MC, Middendorff G, Brooks JM. Effect of hospitalization on inappropriate prescribing in elderly Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:699–707. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:989–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Best O, Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ. Investigating polypharmacy and drug burden index in hospitalised older people. Intern Med J. 2013;43:912–8. doi: 10.1111/imj.12203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hines LE, Murphy JE. Potentially harmful drug-drug interactions in the elderly: a review. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9:364–77. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dechanont S, Maphanta S, Butthum B, Kongkaew C. Hospital admissions/visits associated with drug-drug interactions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:489–97. doi: 10.1002/pds.3592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH. Optimising drug treatment for elderly people: the prescribing cascade. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 1997;315:1096. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wierenga PC, Buurman BM, Parlevliet JL, et al. Association between acute geriatric syndromes and medication-related hospital admissions. Drugs & Aging. 2012;29:691–9. doi: 10.2165/11632510-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert P. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:616–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert P. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227–46. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallagher P, O’Mahony D. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ potentially inappropriate Prescriptions): application to acutely ill elderly patients and comparison with Beers’ criteria. Age Ageing. 2008;37:673–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mant J, Hobbs FDR, Fletcher K, et al. Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study, BAFTA): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2007;370:493–503. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drugs - US Food and Drug Administration. at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/

- 24.Hanlon JT, Artz MB, Pieper CF, et al. Inappropriate medication use among frail elderly inpatients. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:9–14. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morandi A, Vasilevskis EE, Pandharipande PP, et al. Inappropriate medications in elderly ICU survivors: where to intervene? Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1032–4. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmader K, Hanlon JT, Weinberger M, et al. Appropriateness of medication prescribing in ambulatory elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:1241–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.