Abstract

Aims

Injection drug use initiation typically involves an established person who injects drugs (PWID) helping the injection-naïve person to inject. Prior to initiation, PWID may be involved in behaviors that elevate injection initiation risk for non-injectors such as describing how to inject and injecting in front of injection-naïve people. In this analysis, we examine whether PWID who engage in either of these behaviors are more likely to be asked to initiate someone into drug injection.

Methods

Interviews with PWID (N=602) were conducted in California between 2011 and 2013. Multivariate analysis was conducted to determine factors associated with being asked to initiate someone.

Results

The sample was diverse in terms of age, race/ethnicity, and drug use patterns. Seventy-one percent of the sample had ever been asked to initiate someone. Being asked to initiate someone was associated with having injected in front of non-injectors (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR]=1.80, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]=1.12, 2.91), having described injection to non-injectors (AOR=3.63; 95% CI=2.07, 6.36), and doing both (AOR=9.56; 95% CI=4.43, 20.65) as compared to doing neither behavior (referent). Being male (AOR=1.73; 95% CI=1.10, 2.73) and non-injection prescription drug misuse in the last 30 days (AOR=1.69; 95% CI=1.12, 2.53) were also associated with having been asked to initiate someone.

Conclusion

Reducing initiation into injection drug use is an important public health goal. Intervention development to prevent injection initiation should include established PWID and focus on reducing behaviors associated with requests to initiate injection and reinforcing refusal skills and intentions among established PWID.

Keywords: Injection initiation, request to initiate, PWID, social learning theory, observational epidemiology

1. Introduction

1.1. Injection drug use uptake

Injection drug use is a global public health problem. Recent studies indicate that the number of people who inject drugs (PWID) is growing and that drug injection is spreading to new populations and areas (Grau et al., 2007; Lankenau et al., 2012; Mathers et al., 2008; Strathedee and Stockman, 2010; Young and Havens, 2011). PWID are at elevated risk for a wide range of acute and chronic health problems including HIV, HCV, sexually transmitted infections, drug overdose, cellulitis and soft tissue infections, and psychiatric disorders (Aceijas and Rhodes, 2007; Aceijas et al., 2004; Ebright and Pieper, 2002; Khan et al., 2013; Mackesy-Amiti et al., 2012; Mathers et al., 2013; Nelson et al., 2011). Therefore, understanding factors associated with uptake of injection drug use is critical for addressing a variety of public health problems.

The existing empirical literature on injection initiation has relied chiefly on reports by PWID about the circumstances surrounding their first injection (Crofts et al., 1996). While these studies have yielded important insights into motivations, risk factors, and drug-specific experiences related to uptake of injection (Ahamad et al., 2014; Bryant and Treloar, 2007; Chami et al., 2013; Cheng et al., 2006; Day et al., 2005; Doherty et al., 2000; Eaves, 2004; Feng et al., 2013; Fuller et al., 2005, 2001, 2003, 2002; Goldsamt et al., 2010; Kermode et al., 2009, 2007; Lankenau et al., 2007, 2012, 2010; Lloyd-Smith et al., 2009; Mackesy-Amiti et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2011, 2006; Novelli et al., 2005; Ompad et al., 2005; Roy et al., 2010, 2011, 2003; Sherman et al., 2005; Small et al., 2009; Trenz et al., 2012; Valdez et al., 2007, 2011; Werb et al., 2013; Wood et al., 2008; Young and Havens, 2011; Young et al., 2014), they have not examined injection initiation extensively from the viewpoint of established PWID who often assist non-injectors into injection drug use. We know little about behaviors among established PWID that may socialize or promote uptake of injection drug use among non-injectors.

1.2. Social learning theory and injection drug uptake

An emerging empirical literature, informed in part by social learning theory, has begun to identify specific contributions of established PWID to injection initiation. First and foremost, these studies have noted that 68% to 88% of PWID are physically injected by another person the first time they inject, highlighting the essential role of established PWID in the process of injection initiation (Crofts et al., 1996; Rotondi et al., 2014). Second, social processes appear to be critical in generating interest in injecting, and ability to inject, among non-injectors. Behaviors among established PWID, such as injecting in front of non-injectors, describing how to inject, and speaking positively about drug injection are prime examples of social processes related to inject initiation. These behaviors also align with social learning theory, which posits that behavior change occurs through interaction, observation, experimentation, and reinforcement (Bandura, 1977, 1986). Qualitative studies have found the ‘socialization’ impact that PWID can have on people who do not inject drugs includes normalizing injection drug use, reducing stigma, diminishing needle fear or phobia, and demonstrating how drug effects are improved (Fitzgerald et al., 1999; Goldsamt et al., 2010; Harocopos et al., 2009; Kermode et al., 2009; Khobzi et al., 2008; McBride et al., 2001; Sherman et al., 2002; Stillwell et al., 1999; Swift et al., 1999; Tompkins et al., 2007; Witteveen et al., 2006). In addition, research on reducing needle phobia has found that graded exposure to injection is an effective remedy (Trijsburg et al., 1996; Yim, 2006). And lastly, quantitative studies have found that established PWID who describe injection to non-injectors and speak positively about injection to non-injectors are more likely to report past and recent initiation of injection-naïve drug users into drug injection. (Bluthenthal et al., 2014; Rotondi et al., 2014; Strike et al., 2014).

What we do not know is whether describing injection, injecting in front of non-injectors, and speaking positively about injection leads to request for injection initiation. This question is important since drug injection initiation is typically an active process lead by the non-injector (Bryant and Treloar, 2007; Crofts et al., 1996; Harocopos et al., 2009; Simmons et al., 2012). If PWID behaviors are socializing non-injectors into considering injection drug use then reducing or eliminating these socializing behaviors may be another avenue for reducing uptake of injection drug use (Khobzi et al., 2008; Stillwell et al., 1999). To address this issue, we examine if describing injection to non-injectors and injecting in front of non-injectors was associated with being asked to initiate someone into injection drug use.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Procedures

Active PWID were recruited using targeted sampling and community outreach methods in Los Angeles and San Francisco, California (Bluthenthal and Watters, 1995; Kral et al., 2010; Watters and Biernacki, 1989). Enrolled PWID were at least 18 years of age or older and self-reported injection drug use in the past 30 days. Self-reports of recent injection drug use was verified by visual inspection for signs of recent venipuncture (tracks; Cagle et al., 2002). After providing informed consent, PWID completed a survey in a one-on-one session with a trained interviewer. Survey responses were recorded using a computer assisted personal interview program (Questionnaire Development System, NOVA Research, Bethesda, MD). Interviews were conducted from April 2011 to April 2013. Study participants were paid $20 for completing the survey. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at RTI International and the University of Southern California.

2.2. Study Sample

For this analysis, we make use of data from 604 PWID that were asked whether they had ever been asked to initiate someone into injection drug use. This item was added four months into data collection and so was not available for the entire sample. Lastly, to examine gender effects more precisely, we excluded two participants who reported being transgendered, leaving a final sample of 602 participants.

2.3. Study Measures

Our main study outcome variable was being asked to initiate someone into injection. This information was collected with the following item: “Have you ever been asked to help someone inject an illicit drug for the first time?” Participants responding ‘yes’, were then asked how many people had asked them to provide their first injection.

Key explanatory measures related to the social process of initiation included injecting in front of injection-naïve people, describing how to inject to injection-naïve people, injecting others (also referred to an “injection” or “street” doctor) (Kral et al., 1999; Murphy and Waldorf, 1991), and any public injections (that has the potential to be observed by non-injectors). These variables were collected with the following items: “Have you ever explained or described how to inject to someone who had never injected an illicit drug (i.e., a non-injector)?” (Response options, “yes: or “no”); “In the last 12 months, how often have you injected drugs in front of someone who was not already a drug injector?” (Response options, “Always,” “Often,” “Sometimes,” “Rarely,” and “Never”); “In the last 30 days, did you inject another person?” (Response options, “yes” or “no”); and “How often do you inject in public places (e.g., a park, alley, parking lot)?” (Response options, “Always,” “Usually,” “Sometimes,” “Occasionally,” and “Never”). Based on response distribution, we recoded injecting in front of non-injectors and any public injection such that “never” responses equal ‘no’ and all other response equal ‘yes.’ Based on bivariate analysis, we also tested the association of being asked to initiate with the combined variable of injecting in front of and describing injection to non-injectors as follows: 1) No report of either injecting in front of or describing injection to non-injectors, 2) Inject in front of non-injectors only, 3) Describe injection to non-injectors only, and 4) Describe injection to and inject in front of non-injectors.

The following factors were treated as potential covariates: socio-demographic and socioeconomic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, housing status, income, mental health status), drug use history (years of injection), recent (last 30 days) drug use (crack cocaine, powder cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, ‘speedball’-heroin and cocaine admixture, ‘goofball’ – heroin and methamphetamine admixture, non-medical use of prescription drugs including opiates, sedatives, tranquilizers, and stimulants, and marijuana), route of administration (injection and non-injection), and patterns (frequency in the last 30 days), sex partnership patterns (sex partner types and characteristics), and health-related items such as mental health diagnoses (any in life; and specifically, depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and post-traumatic stress disorder) and drug treatment experience (any in lifetime, and last 30 days by methadone detoxification, methadone maintenance, outpatient, residential, and self-help programs). These measures are described in greater detail elsewhere (Arreola et al., 2014; Bluthenthal et al., 2014; Quinn et al., 2014).

Lastly, we were interested how exposure to and information about drug injection related to self-reports of initiating someone into injection ever and in the last 12 months. Data on these issues was collected using the following items: “Have you ever helped someone get their first hit (the first time they ever injected)?” (Response options yes or no). For those who responded ‘yes,’ we next asked, “In the last 12 months, have you helped anyone get their first hit (the first time they ever injected)?”

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (e.g., frequencies, means, standard deviations, among others) were examined for all study variables. We present the results of bivariate and multivariate analyses to determine factors associated with having ever been asked to initiate someone into drug injection. Bivariate comparison of categorical variables used chi-square test and continuous variables used t-test to assess whether they were statistically significantly associated at p<0.05. Correlations among bivariate variables in the same domain (e.g., drug use, demographics, health) were evaluated for multicollinearity. Variables were excluded from the final model if they were significantly correlated with another independent variable in the same domain but had a weaker association with the dependent variable as determined by Pearson correlation. In the multivariate analysis, we used logistic regression to predict ever being asked to initiate someone. The final model included variables significant at the p<0.05 while controlling for confounding and effect modifying (through interaction terms) variables. Variables not significant at the p<0.05 level were removed from the multivariate model.

In addition, we used the linear-by-linear association test to examine the association between the combined variable of injecting in front of and describing injection to non-injectors and self-reports of initiating someone into injection drug use ever and in the last 12 months. All statistics were computed using SPSS/PASW Statistics 18.0 (released July 30, 2009).

3. RESULTS

The socio-demographic characteristics of our sample (N=602) were as follows: 26% female, 36% white, 34% African American, 19% Latino and 11% other race/ethnicities, 51% ≥50 years old (age mean=47.59; standard deviation=11.7; median=50; Interquartile Range [IQR]=41, 56.), and 16% gay, lesbian, or bisexual. The sample was also low-income with 81% of participants reporting a total monthly income of less than $1,351 (less than 150% of federal poverty rate in 2012) and 63% considering themselves homeless at the time of interview. The most common income sources in the last 30 days were illegal or possibly illegal activities (38%), supplemental security income (disability –38%), and general relief/welfare (34%). HIV positive status was reported by 8% of the sample.

Requests to initiate someone into injection were common, with 71% (426/602) of participants reporting having been asked to initiate someone else a total of 12,181 times (mean=29; standard deviation=253.28; median=5; Interquartile range=2, 12). Key demographic and socioeconomic variables associated with having ever been asked to initiate someone into injection included being female, race (whites more likely; African Americans less likely), age cohort (being born in the 1980’s or later), having a steady sex partner, having a casual sex partner who is a PWID, and any police contact in the last six months (Table 1). Health-related variables associated with being asked to initiate were bipolar diagnosis and history of drug treatment. Lastly, 30-day drug use variables associated with having been asked to initiate someone included non-injection use of powder cocaine, opiate prescription medications, tranquilizers, any prescription drug misuse, marijuana, injection drug use of prescription medications and goofballs. Any non-injection drug use and injection of more than one substance were also associated with having been asked to initiate someone.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics by ever asked to initiate someone into drug injection among PWID in Los Angeles and San Francisco, California (N=602)

| Variable | Total (n=602) N (%) |

Never Asked to Initiate (n=176) N (%) |

Ever Asked to Initiate (n=426) N (%) |

P= |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographics | ||||

| Gender | 0.04 | |||

| Female | 155 (26%) | 35 (20%) | 120 (28%) | |

| Male | 447 (74%) | 141 (80%) | 306 (72%) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 215 (36%) | 51 (29%) | 164 (39%) | 0.03 |

| African American | 205 (34%) | 71 (40%) | 134 (32%) | 0.05 |

| Latino | 114 (19%) | 39 (22%) | 75 (18%) | ns |

| Other | 63 (11%) | 15 (9%) | 48 (11%) | ns |

| Study site | ns | |||

| Los Angeles | 307 (51%) | 97 (55%) | 210 (49%) | |

| San Francisco | 295 (49%) | 79 (45%) | 216 (51%) | |

| Age cohorts (born) | ||||

| Pre-1960s | 264 (44%) | 76 (43%) | 188 (44%) | ns |

| 1960s | 181 (30%) | 58 (33%) | 123 (29%) | ns |

| 1970s | 82 (14%) | 28 (16%) | 54 (13%) | ns |

| 1980s or later | 75 (12%) | 14 (8%) | 61 (14%) | 0.03 |

| Steady sex partner in the last 6 months | ns | |||

| Yes | 309(51%) | 82 (47%) | 227 (53%) | |

| Casual sex partner in the last 6 months | 0.03 | |||

| Yes | 188 (31%) | 44 (25%) | 114 (34%) | |

| Paying sex partner in the last 6 months | ns | |||

| Yes | 80 (13%) | 16 (9%) | 64 (15%) | |

| Steady sex partner is an PWID | ns | |||

| Yes | 170 (28%) | 49 (28%) | 121 (28%) | |

| Casual sex partner is an PWID | 0.03 | |||

| Yes | 112 (19%) | 23 (13%) | 89 (21%) | |

| Paying sex partner is an PWID | ns | |||

| Yes | 51 (9%) | 11 (6%) | 40 (9%) | |

| Any police contact in the last 6 months | 0.03 | |||

| Yes | 325 (54%) | 83 (47%) | 242 (57%) | |

| Health-related Items | ||||

| Mental health diagnoses | ||||

| Depression -Yes | 180 (30%) | 58 (33%) | 122 (29%) | ns |

| Bipolar - Yes | 119 (20%) | 24 (14%) | 95 (22%) | 0.02 |

| Schizophrenia – Yes | 66 (11%) | 13 (7%) | 53 (12%) | ns |

| Post-traumatic Stress – Yes | 61 (10%) | 13 (7%) | 48 (11%) | ns |

| Ever in drug treatment by type | ||||

| Methadone Detoxification | 268 (45%) | 66 (38%) | 202 (47%) | 0.03 |

| Methadone maintenance | 254 (42%) | 64 (36%) | 190 (45%) | ns |

| Outpatient | 191 (32%) | 47 (27%) | 144 (34%) | ns |

| Buprenorphine | 57 (10%) | 10 (6%) | 47 (11%) | 0.05 |

| Drug use items | ||||

| Non-injection drug use, last 30 days | ||||

| Powder cocaine | 53 (9%) | 8 (5%) | 45 (11%) | 0.02 |

| Opiate prescription misuse | 140 (23%) | 25 (14%) | 115 (27%) | 0.001 |

| Tranquilizer prescription misuse | 153 (25%) | 34 (19%) | 119 (28%) | 0.03 |

| Marijuana | 331 (55%) | 82 (47%) | 249 (58%) | 0.009 |

| Any prescription drugs | 252 (42%) | 50 (20%) | 202 (28%) | 0.0001 |

| Any non-injection drug use, last 30 days | 0.01 | |||

| Yes | 434 (72%) | 114 (65%) | 320 (75%) | |

| Injected drug use, last 30 days | ||||

| Any prescription drug | 72 (12%) | 14 (8%) | 58 (14%) | 0.05 |

| Goofball (heroin and meth) | 83 (14%) | 15 (9%) | 68 (16%) | 0.02 |

| Injected 2 or more drugs, last 30 days | 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 253 (42%) | 54 (31%) | 199 (47%) | |

| Injection initiation related items | ||||

| Injected other person in last 30 days | 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 171 (28%) | 32 (18%) | 139 (33%) | |

| Any public injection, last 30 days | ns | |||

| Any | 315 (52%) | 82 (47%) | 233 (55%) | |

| Ever inject in front of non-injectors in the last 12 months | 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 232 (39%) | 41 (24%) | 191 (45%) | |

| Ever described injection to non-injector | 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 226 (38%) | 27 (15%) | 199 (47%) | |

| Injection initiation risk categories | 0.0001 | |||

| Neither | 256 (43%) | 112 (65%) | 144 (34%) | |

| Inject in front of non-injectors only | 115 (19%) | 33 (19%) | 82 (19%) | |

| Describe injection to non-injectors only | 109 (18%) | 19 (11%) | 90 (21%) | |

| Both | 117 (20%) | 8 (5%) | 109 (26%) | |

ns = not significant

Among explanatory variables, significant bivariate associations were observed for injecting others, injecting in front of non-injectors, and describing injection to non-injectors. We also examined injecting in front of non-injectors and describing injection as a combined variable with the following categories: 1) Neither behavior reported, 2) injected in front of non-injectors, but did not describe injection, 3) described injection, but did not inject in front of non-injectors, and 4) reported both behaviors. The combined categorical variable was also significantly associated with being asked to initiate someone.

In a multivariate logistic regression model, we found that having injected in front of non-injectors (Adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=1.80; 95% Confidence Interval [CI]=1.12, 2.91), having described injection to non-injectors (AOR=3.63; 95% CI=2.07, 6.36) and having done both (AOR=9.56; 95% CI=4.43, 20.65) were significantly associated with having been asked to initiate someone into injection (Table 2). In addition, being male (AOR=1.73; 95% CI=1.10, 2.73) and non-injection use of any prescription drug in the last 30 days (AOR=1.69; 95% CI=1.12, 2.53) were also associated with having been asked to initiate someone into drug injection.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with ever being asked to initiate someone into injection drug use (N=602)

| Variables | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Injection initiation risk categories | ||

| Neither | referent | |

| Inject in front on non-injectors only | 1.80 | (1.12, 2.91) |

| Describe injection to non-injectors only | 3.63 | (2.07, 6.36) |

| Both | 9.56 | (4.43, 20.65) |

| Male | ||

| Yes | 1.73 | (1.10, 2.73) |

| Non-injection, non-medical prescription drug use in the last 30 days | ||

| Yes | 1.69 | (1.12, 2.53) |

Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness of Fit Test (X2)= 6.249

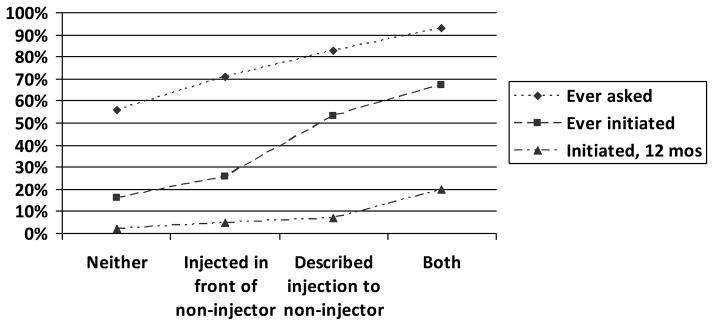

Lastly, to further explore associations between being asked to initiate and actually doing so, we display responses to the combined injecting in front of and describing injection to non-injectors by these outcomes (Figure 1). A significant association was observed for combined injecting in front of and describing injection to non-injector variable for asked to initiate (X2=61.81; p<0.0001), initiated someone in the last 12 months (X2=36.12; p<0.0001) and ever initiated someone into injection (X2=108.85; p<0.0001).

Figure 1.

Injection initiation categories by being asked to initiate someone, ever initiating someone and initiating someone into injection drug use in the last 12 months (n=602).

4. DISCUSSION

In keeping with social learning theory (Bandura, 1977, 1986), we found that injecting in front of non-injectors and describing injection to non-injectors were significantly associated with being asked to initiate non-injectors, even in the context that most PWID had been asked to initiate someone. There was a significant interaction between these variables, such that people who had both injected in front of and described injection to non-injectors were at even higher odds of having been asked to initiate someone. This finding lends support to the idea that injection drug use is communicable (Crofts et al., 1996; Khobzi et al., 2008; Stillwell et al., 1999; Strike et al., 2014). Indeed, as we demonstrated in Figure 1, increased involvement in these behaviors is associated with ever being asked, ever initiating, and initiating someone into injection in the last 12 months. Given this, approaches to preventing injection initiation that involve established PWID are warranted. Our data suggest that such interventions should include a focus on reducing injection in front of and describing injection to non-injectors among active PWID.

In addition, males were at higher odds of having been asked to initiate non-injectors into drug injection. There is a substantial literature on gender and injection initiation with many studies (Eaves, 2004; Roy et al., 2010; Simmons et al., 2012; Stenbacka, 1990), but not all (Bryant and Treloar, 2007; Doherty et al., 2000), finding that men are more likely to initiate non-injectors as compared to women. In our own analysis of initiating non-injectors in the last 12 months, we found that men were no more likely to initiate a non-injector than women (Bluthenthal et al., 2014). This finding is consistent with other studies about initiation that have not found this behavior to be associated with gender (Bryant and Treloar, 2008; Rotondi et al., 2014; Strike et al., 2014). With this in mind, it is likely that the gender difference in initiators as reported by PWID may be explained by the simple fact that PWID are disproportionately male (Lansky et al., 2014; Tempalski et al., 2013).

Lastly, we found that PWID who reported non-injection use of prescription medications (any opiates, tranquilizers, depressants or stimulant medication) had significantly higher odds of having been asked to initiate someone. We suspect this association is due to changing trends in subpopulations that are at risk for transitioning into drug injection. Increased nonmedical use of prescription drugs has been widely reported in the US (Manchikanti et al., 2012), Canada (Bruneau et al., 2012; Nosyk et al., 2012), and Australia (Blanch et al., 2014). The rise of prescription drug misuse, particularly in the form of opiate pain medications, appears to be related to an increase in heroin use and injection drug use in the United States and elsewhere (Cicero et al., 2014; Jones, 2013; Peavy et al., 2012). We suspect that PWID who reported nonmedical use of prescription drugs were more likely to be in contact with non-injecting users of prescription drugs, a population that may be at elevated risk for transitioning to injection drug use (Mars et al., 2014; Pollini et al., 2011). More research on the drug use characteristics of social networks of PWID are needed to substantiate this potential connection between request for initiation and drug use patterns. Nevertheless, people who use prescription drugs non-medically should be considered a high priority population upon which to focus interventions that prevent transition to injection drug use.

Results from this exploratory study should be considered in light of the following limitations. This is a cross-sectional study, so causality cannot be determined and should not be inferred. Further, all data are based on self-reports from participants, which means they are potentially subject to response bias resulting from social desirability and lack of accurate recall. In addition, inconsistent time frames were used for key variables with some characterizing lifetime behaviors (i.e., describing injection to non-injectors, being asked to initiate someone into injection), last 12 months (i.e., injecting in front of non-injectors), last 6 months (i.e., sexual partner types), and last 30 days (i.e., drug use). Most study measures were selected based on their strong psychometric properties (Dowling-Guyer et al., 1994; Fisher et al., 2007; Needle et al., 1995; Weatherby et al., 1994), however, our measures on injection initiation risk behaviors have not been fully tested for reliability or validity. Future research involving longitudinal cohorts and consistent time frames are recommended. Reliability and validity testing of injection initiation variables are also warranted.

The current study contributes to the growing body of research that identifies established PWID as important contributors to the ongoing epidemic of injection drug use (Bluthenthal et al., 2014; Bryant and Treloar, 2008; Kral et al., 2014; Rotondi et al., 2014; Strike et al., 2014). Its focus on how describing injection to and injecting in front of non-injectors may contribute to requests to initiate someone into injection is novel. Our finding that these injection initiation risk behaviors are in fact associated with request to initiate injection is additional evidence for the communicable nature of injection drug use (Crofts et al., 1996; Strike et al., 2014). Therefore, approaches to preventing injection initiation should include efforts to change both willingness to initiate and behaviors that promote request for initiation, such as injecting in front of or describing injection to non-injectors.

There is at least one promising intervention – ‘Change the Cycle’ (Strike et al., 2014) - to reduce injection initiation risk behaviors among PWID. This hour-long, one-on-one, active listening and social learning intervention has been found to reduce episodes of injection initiation in one pilot study (Strike et al., 2014). Full-scale trial testing of this intervention is urgently needed, followed by rapid dissemination and implementation if it is found to be efficacious. Other approaches should also be developed and could include social marketing strategies (“Breaking the Cycle” includes a social marketing component- Hunt et al., 1998), safer injection facilities and housing programs that reduce exposure of non-injectors to injection processes and effects. “Breaking the Cycle” has been disseminated in several countries and has generally been found to be feasible and accepted to PWID populations although a randomized controlled trial of this intervention has yet to be conducted (Stillwell et al., 2005).

Initiation of injection drug use represents a significant escalation of health risk including greater odds of acquiring HIV, HCV, abscesses and soft tissue infections, and drug overdose among others (Aceijas and Rhodes, 2007; Aceijas et al., 2004; Britton et al., 2010; Ebright and Pieper, 2002; Khan et al., 2013; Nelson et al., 2011; Silva et al., 2013). Efforts to reduce injection initiation are urgently needed and should involve interventions focused on both high risk non-PWID and established PWID who are instrumental to injection initiation in many cases.

Social learning theory and empirical observations suggest that active people who inject drugs (PWID) are instrumental to the uptake of injection among non-injecting drug users.

Behaviors previously understood to promote transition into drug injection are associated with request to inject for the first time.

Active PWID contribute to the spread of injection drug use.

Acknowledgments

Funding.

The research was supported by NIDA (grant # R01DA027689: Program Official, Elizabeth Lambert) and in part by the National Cancer Institute (grant # P30CA014089).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank the participants who took part in this study. The following research staff and volunteer also contributed to the study and are acknowledged here: Sonya Arreola, Vahak Bairamian, Philippe Bourgois, Soo Jin Byun, Jose Collazo, Jacob Curry, David-Preston Dent, Karina Dominguez, Jahaira Fajardo, Richard Hamilton, Frank Levels, Luis Maldonado, Askia Muhammad, Brett Mendenhall, Stephanie Dyal-Pitts, and Michele Thorsen.

Footnotes

Contributors.

Ricky Bluthenthal designed the study (along with Alex Kral), conducted the statistical analysis, and prepared drafts of the manuscript. Ricky Bluthenthal and Lynn Wenger managed the literature searches and summaries of previous related work. Lynn Wenger managed the study protocol. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest.

The authors have no financial relationships that are related to the topic of this manuscript and no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aceijas C, Rhodes T. Global estimates of prevalence of HCV infection among injecting drug users. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aceijas C, Stimson GV, Hickman M, Rhodes T. Global overview of injecting drug use and HIV infection among injecting drug users. AIDS. 2004;18:2295–2303. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200411190-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahamad K, deBeck K, Feng C, Sakakibara T, Kerr T, Wood E. Gender influences on initiation of injecting drug use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40:151–156. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.860983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreola S, Bluthenthal RN, Wenger L, Chu D, Thing J, Kral AH. Characteristics of people who initiate injection drug use later in life. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;138:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. Prentice Hall Inc; Englewood Cliffs, N.J: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice Hall Inc; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Blanch B, Pearson S, Haber PS. An overview of the patterns of prescription opioid use, costs and related harms in Australia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78:1159–66. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN, Watters JK. Multimethod research from targeted sampling to HIV risk environments. NIDA Res Monogr. 1995;157:212–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN, Wenger L, Chu D, Quinn B, Thing J, Kral AH. Factors associated with initiating someone into illicit drug injection. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;144:186–92. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton PC, Wines JDJ, Conner KR. Non-fatal overdose in the 12 months following treatment for substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;107:51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau J, Roy E, Arruda N, Zang G, Justras-Aswad D. The rising prevalence of prescription opioid injection and its association with hepatitis C incidence among street-drug users. Addiction. 2012;107:1318–1327. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant J, Treloar C. The gendered context of initiation to injecting drug use: evidence for women as active initiates. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26:287–293. doi: 10.1080/09595230701247731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant J, Treloar C. Initiators: an examination of young injecting drug users who initiate others to injecting. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:885–890. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9347-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagle HH, Fisher DG, Senter TP, Thurmond RD, Kastar AJ. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, editor. Classifying Skin Lesions of Injection Drug Users: A Method for Corroborating Disease Risk. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chami G, Werb D, Feng C, DeBeck K, Kerr T, Wood E. Neighborhood of residence and risk of initiation into injection drug use among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:486–490. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Sherman SG, Srirat N, Vongchak T, Kawichai S, Jittiwutikarn J, Suriyanon V, Razak MH, Sripaipan T, Celentano DD. Risk factors associated with injection initiation among drug users in Northern Thailand. Harm Reduct J. 2006;3:10. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: a retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:821–826. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofts N, Louie R, Rosenthal D, Jolley D. The first hit: circumstances surrounding initiation into injecting. Addiction. 1996;91:1187–1196. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.918118710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day CA, Ross J, Dietze P, Dolan K. Initiation to heroin injecting among heroin users in Sydney, Australia: cross-sectional survey. Harm Reduct J. 2005;15:2. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty MC, Garfein RS, Monterroso E, Latkin C, Vlahov D. Gender differences in the initiation of injection drug use among young adults. J Urban Health. 2000;77:396–414. doi: 10.1007/BF02386749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling-Guyer S, Johnson ME, Fisher DG, Needle R, Watters JK, Andersen M, Williams M, Kotranski L, Booth R, Rhodes F, Weatherby N, Estrada AL, Fleming D, Deren S, Tortu S. Reliability of drug users’ self-reported HIV risk behaviors and validity of self-reported recent drug use. Assessment. 1994;1:383–392. [Google Scholar]

- Eaves CS. Heroin use among female adolescents: the role of partner influence in path of initiation and route of administration. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:21–38. doi: 10.1081/ada-120029864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebright JR, Pieper B. Skin and soft tissue infectious in injection drug users. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002;16:697–712. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(02)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C, DeBeck K, Kerr T, Mathias S, Montaner J, Wood E. Homelessness independently predicts injection drug use initiation among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:499–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DG, Reynolds GL, Jaffe A, Johnson ME. Reliability, sensitivity and specificity of self-report of HIV test results. AIDS Care. 2007;19:692–696. doi: 10.1080/09540120601087004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald JL, Louie R, Rosenthal D, Crofts N. The meaning of the rush for initiates to injecting drug user. Contemp Drug Probl. 1999;26:481–504. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Borrell LN, Latkin CA, Galea S, Ompad DC, Strathdee SA, Vlahov D. Effects of race, neighborhood, and social network on age at initiation of injection drug use. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:689–695. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.02178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Vlahov D, Arria AM, Ompad DC, Garfein R, Strathdee SA. Factors associated with adolescent initiation of injection drug use. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(Suppl 1):136–145. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Vlahov D, Latkin CA, Ompad DC, Celentano DD, Strathdee SA. Social circumstances of initiation of injection drug use and early shooting gallery attendance: implications for HIV intervention among adolescent and young adult injection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:86–93. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200301010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Vlahov D, Ompad DC, Shah N, Arria A, Strathdee SA. High-risk behaviors associated with transition from illicit non-injection to injection drug use among adolescent and young adult drug users: a case-control study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsamt LA, Harocopos A, Kobrak P, Jost JJ, Clatts MC. Circumstances, pedagogy and rationales for injection initiation among new drug injectors. J Community Health. 2010;35:258–267. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9231-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau LE, Dasgupta N, Harvey AP, Irwin K, Givens A, Kinzly ML, Heimer R. Illicit use of opioids: is OxyContin a “gateway drug”? Am. J Addict. 2007;16:166–173. doi: 10.1080/10550490701375293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harocopos A, Goldsamt LA, Kobrak P, Jost JJ, Clatts MC. New injectors and the social context of injection initiation. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt N, Stillwell G, Taylor C, Griffiths P. evaluation of a brief intervention to prevent initiation into injecting. Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 1998;5:185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM. Heroin use and heroin use risk behaviors among nonmedical users of prescription opioid pain relievers - United States, 2002–2004 and 2008–2010. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kermode M, Longleng V, Singh BC, Bowen K, Rintoul A. Killing time with enjoyment: a qualitative study of initiation into injecting drug use in north-east India. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44:1070–1089. doi: 10.1080/10826080802486301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kermode M, Longleng V, Singh BC, Hocking J, Langkham B, Crofts N. My first time: initiation into injecting drug use in Manipur and Nagaland, north-east India. Harm Reduct J. 2007;4:19. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-4-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MR, Berger A, Hemberg J, O’Neill A, Dyer TP, Smyrk KK. Non-injection and injection drug use and STI/HIV risk in the United States: the degree to which sexual risk behaviors versus sex with an STI-infected partner account for infection transmission among drug users. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:1185–1194. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0276-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khobzi N, Strike C, Cavalieri W, Bright R, Myers T, Calzavara L, Millson M. Initiation into injection: necessary and background processes. Addict Res Theory. 2008;17:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kral AH, Bluthenthal RN, Erringer EA, Lorvick J, Edlin BR. Risk factors among IDUs who give injections to or receive injections from other drug users. Addiction. 1999;94:675–683. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9456755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral AH, Malekinejad M, Vaudrey J, Martinez AN, Lorvick J, McFarland W, Raymond HF. Comparing respondent-driven sampling and targeted sampling methods of recruiting injection drug users in San Francisco. J Urban Health. 2010;87:839–850. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9486-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral AH, Wenger L, Chu D, Quinn B, Thing J, Bluthenthal RN. Initiating People Into Illicit Drug Injection. 76th Annual Meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence; San Juan, Puerto Rico. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau SE, Sanders B, Bloom JJ, Hathazi D, Alarcon E, Tortu S, Clatts MC. First injection of ketamine among young injection drug users (IDUs) in three U.S. cities. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau SE, Teti M, Silva K, Jackson Bloom J, Harocopos A, Tresse M. Initiation into prescription opioid misuse amongst young injection drug users. Int J Drug Policy. 2012;23:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau SE, Wagner KD, Jackson Bloom J, Sanders B, Hathazi D, Shin C. The first injection event: differences among heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine, and ketamine initiates. J Drug Issues. 2010;40:241–262. doi: 10.1177/002204261004000201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansky A, Finlayson T, Johnson C, Holtzman D, Wejnert C, Mitsch A, Gust D, Chen R, Mizuno Y, Crepaz N. Estimating the number of persons who inject drugs in the United States by meta-analysis to calculate national rates of HIV and hepatitis C virus infections. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Smith E, Wood E, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Incidence and determinants of initiation into cocaine injection and correlates of frequent cocaine injectors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackesy-Amiti ME, Boodram B, Williams C, Ouellet LJ, Broz D. Sexual risk behavior associated with transition to injection among young non-injecting heroin users. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2459–2466. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0335-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackesy-Amiti ME, Donenberg GR, Ouellet LJ. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among young injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchikanti L, Helms Sn, Fellows B, Janata W, Pampati V, Grider JS, Boswell MV. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician. 2012;15:ES9–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars SG, Bourgois P, Karandinos G, Montero F, Ciccarone D. “Every ‘Never’ I ever said came true”: transitions from opioid pills to heroin injecting. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers B, Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Lemon J, Wiessing L, Hickman M. Mortality among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:102–123. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.108282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Strathdee SA, Wodak A, Panda S, Tyndall M, Toufik A, Mattick RP. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet. 2008;372:1733–1745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride AJ, Pates RM, Arnold K, Ball N. Needle fixation, the drug user’s perspective: a qualitative study. Addiction. 2001;96:1049–1058. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.967104914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Pearce ME, Moniruzzaman A, Thomas V, Christian W, Schechter MT, Spittal PM. The Cedar Project: risk factors for transition to injection drug use among young, urban Aboriginal people. CMAJ. 2011;183:1147–1154. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Strathdee SA, Kerr T, Li K, Wood E. Factors associated with early adolescent initiation into injection drug use: implications for intervention programs. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:462–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy S, Waldorf D. ‘Kickin’ down to the street doc: shooting galleries in the San Francisco Bay Area. Contemp Drug Probl. 1991;18:9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Needle RN, Fisher DG, Weatherby N, Chitwood D, Brown B, Cesari H, Booth R, Williams ML, Watters JK, Andersen M, Braunsterin M. Reliability of self-reported HIV risk behaviors of drug users. Psychol Addict Behav. 1995;9:242–250. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PK, Mathers BM, Cowie B, Hagan H, Des Jarlais D, Horyniak D, Degenhardt L. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: results of systematic reviews. Lancet. 2011;378:571–583. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61097-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyk B, Marshall BD, Fischer B, Montaner JS, Wood E, Kerr T. Increases in the availability of prescribed opioids in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novelli LA, Sherman SG, Havens JR, Strathdee SA, Sapun M. Circumstances surrounding the first injection experience and their association with future syringe sharing behaviors in young urban injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ompad DC, Ikeda RM, Shah N, Fuller CM, Bailey S, Morse E, Kerndt P, Maslow C, Wu Y, Vlahov D, Garfein R, Strathdee SA. Childhood sexual abuse and age at initiation of injection drug use. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:703–709. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.019372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peavy KM, Banta-Green CJ, Kingston S, Hanrahan M, Merrill JO, Coffin PO. “Hooked on” prescription-type opiates prior to using heroin: results from a survey of syringe exchange clients. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2012;44:259–265. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2012.704591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollini RA, Banta-Green CJ, Cuevas-Mota J, Metzner M, Teshale E, Garfein RS. Problematic use of prescription-type opioids prior to heroin use among young heroin injectors. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2011;2:173–180. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S24800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn B, Chu D, Wenger L, Bluthenthal R, Kral AH. Syringe disposal among people who inject drugs in Los Angeles: the role of sterile syringe source. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25:905–910. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotondi NK, Strike C, Kolla G, Rotondi MA, Rudzinski K, Guimond T, Roy E. Transition to injection drug use: the role of initiators. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:486–494. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0693-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy E, Boivin JF, Leclerc P. Initiation to drug injection among street youth: a gender-based analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;114:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy E, Godin G, Boudrenu JF, Cote PB, Denis V, Haley N, Leclerc P, Boivin JF. Modeling initiation into drug injection among street youth. J Drug Educ. 2011;41:119–134. doi: 10.2190/DE.41.2.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy E, Haley N, Leclerc P, Cedras L, Blais L, Boivin JF. Drug injection among street youths in Montreal: predictors of initiation. J Urban Health. 2003;80:92–105. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SG, Fuller CM, Shah N, Ompad DV, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA. Correlates of initiation of injection drug use among young drug users in Baltimore, Maryland: the need for early intervention. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2005;37:437–443. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2005.10399817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SG, Strathdee S, Smith L, Laney G. Spheres of influence in transitioning to injection drug use: a qualitative study of young injectors. Int J Drug Policy. 2002;13:113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Silva K, Schrager SM, Kecojevic A, Lankenau SE. Factors associated with history of non-fatal overdose among young nonmedical users of prescription drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons J, Rajn S, McMahon JM. Retrospective accounts of injection initiation in intimate partnerships. Int J Drug Policy. 2012;23:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Fast D, Krusi A, Wood E, Kerr T. Social influences upon injection initiation among street-involved youth in Vancouver, Canada: a qualitative study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2009;4:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenbacka M. Initiation into intravenous drug abuse. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;81:459–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb05481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillwell G, Hunt N, Preston A. Population Services International. USAID; 2005. A survey of drug route transitions among non-injecting and injecting heroin users in South Eastern Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Stillwell G, Hunt N, Taylor C, Griffiths P. The modelling of injecting behavior and initiation into injection. Addict Res. 1999;7:447–459. [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Stockman JK. Epidemiology of HIV among injecting and non-injecting drug users: current trends and implications for interventions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7:99–106. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0043-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strike C, Rotondi M, Kolla G, Roy E, Rotondi NK, Rudzinski K, Balian R, Guimond T, Penn R, Silver RB, Millson M, Sirois K, Altenberg J, Hunt N. Interrupting the social processes linked with initiation of injection drug use: results from a pilot study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;137:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift W, Maher L, Sunjic S. Transitions between routes of heroin administration: a study of Caucasian and Indochinese heroin users in south-western Sydney, Australia. Addiction. 1999;94:71–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempalski B, Pouget ER, Cleland CM, Brady JE, Cooper HL, Hall HI, Lansky A, West BS, Friedman SR. Trends in the population prevalence of people who inject drugs in US Metropolitan Areas 1992–2007. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins CNE, Ghoneim S, Wright NMJ, Sheard L, Jones L. Needle fear among women injecting drug users: a qualitative study. J Subst Use. 2007;12:281–291. [Google Scholar]

- Trenz RC, Harrell P, Scherer M, Mancha BE, Latimer WW. A model of school problems, academic failure, alcohol initiation, and the relationship to adult heroin injection. Subst Use Misuse. 2012;47:1159–1171. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2012.686142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trijsburg RW, Jelicic M, van der Broek WW, Plekker AE, Verheij R, Passchier J. Exposure and participant modelling in a case of injection phobia. Psychother Psychosom. 1996;65:57–61. doi: 10.1159/000289033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez A, Neaigus A, Cepeda A. Potential risk factors for injecting among Mexican American non-injecting heroin users. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2007;6:49–73. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n02_05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez A, Neaigus A, Kaplan C, Cepeda A. High rates of transitions to injecting drug use among Mexican American non-injecting heroin users in San Antonio, Texas (never and former injectors) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;114:233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watters JK, Biernacki P. Targeted sampling: options for the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1989;36:416–430. [Google Scholar]

- Weatherby N, Needle RH, Cesari H, Booth R, McCoy CB, Watters JK, Williams M, Chitwood DD. Validity of self-reported drug use among injection drug users recruited through street outreach. Eval Prog Plann. 1994;17:347–355. [Google Scholar]

- Werb D, Kerr T, Buxton J, Shoveller J, Richardson C, Montaner J, Wood E. Crystal methamphetamine and initiation of injection drug use among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting. CMAJ. 2013;185:1569–1575. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.130295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witteveen E, Van Ameijden EJ, Schippers GM. Motives for and against drug use among young adults in Amsterdam: qualitative findings and considerations for disease prevention. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41:1001–1016. doi: 10.1080/10826080600669561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Stoltz JA, Zhang R, Strathdee SA, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Circumstances of first crystal methamphetamine use and initiation of injection drug use among high-risk youth. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27:270–276. doi: 10.1080/09595230801914750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim L. Belonephobia -- a fear of needles. Aust Fam Physician. 2006;35:623–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, Havens JR. Transitions from illicit drug use to first injection drug use among rural Appalachian drug users. Addiction. 2011;107:587–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, Larian N, Havens JR. Gender differences in circumstances surrounding first injection experience of rural injection drug users in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;134:401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]