ABSTRACT

Purpose: There is inconclusive evidence to suggest the expression of programmed cell death (PD) ligand 1 (PD-L1) is a putative predictor of response to PD-1/PD-L1-targeted therapies in lung cancer. We evaluated the heterogeneity in the expression of PD-1 ligands in isogeneic primary and metastatic LC specimens. Experimental Design: From 12,580 post mortem cases, we identified 214 patients with untreated metastatic LC, of which 98 had adequately preserved tissues to construct a syngeneic primary LC/metastasis tissue microarray. Immunostaining for PD-L1 and 2 was evaluated in paired primary and metastatic lesions and correlated with clinicopathologic features. Results: We included 98 patients with non-small cell (NSCLC, n = 65, 66%), small cell histology (SCLC, n = 29, 30%) and four (4%) atypical carcinoids (AC). In total 8/65 (12%) primary PD-L1 positive NSCLC, had discordant matched metastases (14/17, 82%). PD-L1 negative primaries had universally concordant distant metastases. SCLCs were universally PD-L1 negative across primary and metastatic disease. PD-L2 positive NSCLC (n = 11/65, 17%) had high rate of discordant metastases (n = 24/27, 88%) and four cases (6%) had PD-L2 positive metastases with negative primaries. 2/29 SCLC (7%) and 1/4 AC (25%) were PD-L2 positive with discordance in all the sampled metastatic sites (n = 5). We found no correlation between the expression of PD ligands and clinicopathologic features of LC. Conclusions: Intra-tumoral heterogeneity in the expression of PD ligands is common in NSCLC, while PD-L1 is homogeneously undetectable in primary and metastatic SCLC. This holds implications in the clinical development of immune response biomarkers in LC.

KEYWORDS: Heterogeneity, lung cancer, PD-1, PD-L1, PD-L2

Introduction

Therapeutic modulation of the programmed cell death (PD-1) receptor–ligand interaction, a major pathway governing antitumor immune control, has been proven effective in lung cancer (LC).1,2 While immune checkpoint inhibition has translated into improved overall survival, the depth and duration of response to treatment is highly heterogeneous in patients with LC.3 Increasing research efforts are therefore being addressed to the discovery of biomarkers to improve the selection of patients who might benefit from immune checkpoint inhibition.

PD-L1 expression status has emerged as a putative predictive marker of response to PD-1/PD-L1-directed therapies ever since the first early-phase clinical trials,4 supported by the rationale that the expression of the drug target within the tumor tissue and/or the surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate prior to treatment might predict for an enhanced biologic activity of immunotherapy. While biologically plausible, this rationale has conflicted with the clinical observation that patients with PD-L1 negative tumors may achieve an inferior but equally significant survival benefit from immune checkpoint inhibition.5

A number of biologic and technical explanations have emerged with time in an attempt to understand the sources of variability in PD-L1 status assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC).6 A key factor that has consolidated in lung as well as in other malignancies, is the heterogeneous expression of PD ligands across different tumor sites.7-9 In LC, previous reports have shown heterogeneous expression of PD-L1 in multifocal lung malignancies, a finding that has important clinical implications in the accurate allocation of patients to immunotherapy based on of PD-L1 expression status on archival diagnostic material.7 While heterogeneity in PD ligands expression status has been further identified studied in primary and matched lymphnode metastases of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the lung,10 little is known about the differential expression of PD ligands in the context of the metastatic spread of the various histotypes of LC, including both non-small cell (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC), where initial reports have shown highly histotype-dependant expression levels.11

We therefore designed this study to comprehensively assess the intra-tumor heterogeneity of PD-1 and PD-1 ligands expression in a consecutive series of matched primary and metastatic LC specimens. To test our hypothesis, we used a robustly quality-controlled post mortem (PM) case series to construct an isogeneic collection of LC specimens, with adequate representation of all the major histotypes.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

The Royal Postgraduate Medical School archives were searched to identify samples of metastatic LC suitable for this analysis. The reports of 12,580 PM examinations performed at the Hammersmith Hospital between January 1970 and December 2005 were reviewed. LC was identified in 499 cases. Patients who received any form of active anticancer therapy for their malignancy were excluded (n = 286) to avoid the confounding effect of treatment on PD-L1 and 2 expression.12 In total, formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks pertaining to 213 patients had not received any active anticancer therapy for their malignancy were retrieved from the archives. These patients were further screened for stringent tissue quality criteria, including (1) confirmed histopathologic diagnosis of metastatic LC; (2) lack of significant autolytic degeneration of the target tissues; (3) complete PM dissection of all the organs; and (4) PM interval <24 h from death.

Histotype classification as well as metastatic distribution was confirmed following review of newly cut Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) sections by a consultant pulmonary pathologist (FAM). Tumor stage was reconstructed following the TNM criteria 7th edition (14). The suitability of both primary and metastatic deposits to immunohistochemical (IHC) studies was confirmed following preliminary immunostaining for two pan-cytokeratin markers: MNF116 (Dako, Cambridge, UK) incubated at 1:200 concentration for 1 h and CK Cam 5.2 (BD Biosciences, USA) incubated at 1:20 concentration for 1 h after 0.1% trypsin in phosphate buffered saline incubation for 10 min. PM specimens showing dubious or unsatisfactory MNF116/CK Cam 5.2 staining were discarded. Based on the combination of the above quality criteria, a total number of 98 cases were considered suitable to be included in the study.

Clinicopathological variables including gender, age at death, tumor staging together with the number and distribution of metastatic sites were recorded. The absence of any chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment was confirmed by PM reports and medical notes review. This study protocol received full approval by an accredited Research Ethics Committee (Reference: 06/Q0406/154).

Tissue microarray (TMA) construction

Combined primary tumor/metastasis TMA blocks were prepared as previously described (15). Following marking of diagnostic H&E slides, we used an MTA-1 Manual Tissue Microarrayer (Beecher Instruments, USA) to obtain 1 mm cores from separate areas of the primary tumors and matched secondary lesions to ensure maximal reproducibility and re-embedded the tissue cores in recipient microarray blocks. All primary and metastatic deposits were sampled in triplicate. Adequate sampling of the target lesions was confirmed on a freshly cut H&E section from the recipient TMA block before immunostaining.

Immunohistochemistry

TMA block sectioning and IHC staining was performed at the Imperial College Histopathology Laboratory (Hammersmith Hospital, London) using the Leica Bond RX stainer (Leica, Buffalo, IL). Tissues were sectioned at 5 microns. De-identified human tonsil sections retrieved from the diagnostic histopathology laboratory were used as positive control tissue. Omission of the primary antibody on tonsil sections served as negative control reaction. Positive and negative controls were run with test samples in a single batch for each tested antibody.

Antigen retrieval was carried out using standard procedures: briefly, the sections were de-paraffinized in xylene, rehydrated in graded alcohols and heated in a microwave oven at 900 W for 20 min in citrate buffer at pH 6.0 (16). For optimal antigen retrieval, tissue slides were incubated in citrate buffer at pH 6.0 for 30 min prior to PD-L1 immunostaining and 20 min for PD-L2. Before immunostaining, slides were cooled at room temperature and endogenous peroxidase activity was suppressed by incubation with a 3% solution of H2O2 for 5 min. Primary antibodies anti-PD-L1 (Clone E1L3N; Cell Signaling Cat. Nr. 13684) and anti-PD-L2 (Sigma Aldrich, Cat. Nr. 3500395,) were incubated overnight at the concentration 1:100 and 1:300, respectively. Tissue sections were then incubated with the secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature and then processed using the Polymer-HRP Kit (BioGenex, San Ramon CA, US) with development in Diaminobenzidine and Mayer's Haematoxylin counterstaining.

Biomarker expression scoring

IHC expression of the candidate biomarkers was evaluated taking into account the percentage of cells staining positively and the intensity of the signal to derive a semi-quantitative histoscore as described before.13 For all the tested biomarkers, we considered specific tumor cell or peritumoral stromal expression only if membranous or concomitant membranous and cytoplasmic staining were present.

Due to the focal nature of PD-L1 expression in tumor samples, we followed pre-specified methodology in classifying PD-L1 status categorically.2 Specimens displaying at least moderate intensity and >5% proportion of PD-L1 staining of tumor or immune cells were considered positive. To ensure reproducibility of the scoring system, two observers (FAM, DJP) scored all the cases independently and results were found to be consistent.

Statistical analysis

Pearson's Chi square or Fisher's exact tests were used to elucidate any significant associations between categorical variables as appropriate. Associations were considered statistically significant when the resulting p value was <0.05. Analysis was performed using SPSS software version 11.5 (SPSS inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad PRISM (GraphPad software inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Patients and tumor characteristics

The clinicopathological features reconstructed from the 98 PM included in the study are summarized in Table 1. The predominant histological subtype was NSCLC (n = 65, 66%). At the time of death, 76% of the subjects had evidence of distant metastases.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic features of the studied population.

| Patient characteristic | N = 98 |

|---|---|

| Age at death, median (range) | 70 (43–93) |

| Gender, M/F | 73/25 |

| Histopathological classification | |

| NSCLC | 65 (66) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 30 (31) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 32 (33) |

| Adeno-squamous carcinoma | 3 (2) |

| SCLC | 29 (30) |

| Atypical carcinoid | 4 (4) |

| TNM stage | |

| II–III | 21 (21) |

| IV a | 3 (3) |

| IV b | 74 (76) |

| SCLC stage | |

| Limited disease | 4 (14) |

| Extensive disease | 25 (86) |

In NSCLC cases, the most frequent sites of metastasis were locoregional lymphnodes in 56 patients (86%) followed by liver (n = 31, 48%), adrenal (n = 26, 41%), bone and brain (n = 21, 32%) each. Commonest sites of SCLC metastases were liver (n = 21, 72%), bone (n = 14, 48%) and brain (n = 12, 41%).

Expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 in primary lung cancer and matched metastatic deposits

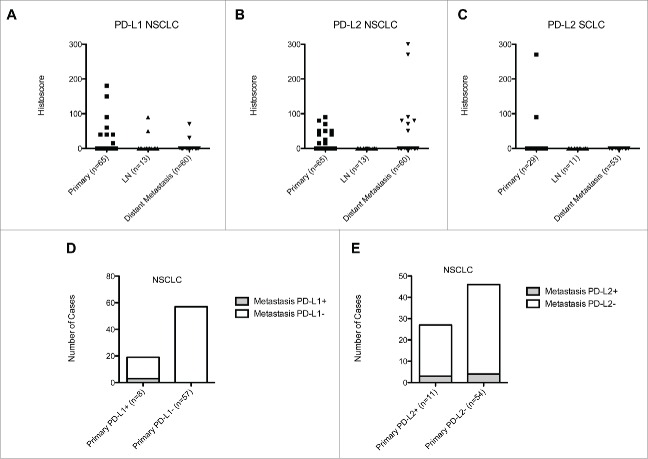

TMA blocks were constructed to include a total of 98 independent primary LC samples and 137 paired metastases (73 from NSCLC and 64 from SCLC) for a total of 705 individual tissue cores. The distribution and intensity of PD-L1 and PD-L2 immunopositivity across primary and metastatic disease is presented in Fig. 1. Representative sections of PD-L1 and PD-L2 expressing tumors are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot illustrating the distribution of PD-L1 and PD-L2 immunoreactivity expressed by histoscore values across primary tumors, lymphnode and visceral metastases of NSCLC (Panels A and B) and SCLC (Panel C). Panels (D)and (E)describe the heterogeneity in the expression of PD-L1 (Panel D) and PD-L2 (Panel E) across paired primary and metastatic NSCLC deposits stratified according to PD-L1 and PD-L2 primary tumor expression status.

Figure 2.

Representative sections showing a case of primary SCLCs are shown at 100× magnification. Panel (A)shows a case staining negatively for PD-L1. A case of PD-L2 expressing SCLC is shown in Panel B. Panel (C)shows a case of a PD-L1 positive primary lung adenocarcinoma. Strongly positive PD-L1 tumor cells are abutting an area of tumor necrosis and are associated with a strong lymphocytic infiltrate. Panels (D)and (E)show representative sections of a strongly PD-L2 positive and PD-L2 negative primary lung adenocarcinomas.

In total, eight (12%) primary NSCLC were PD-L1 positive. Median histoscore was 50 (range 15–180). The clinicopathologic features of these patients are presented in Table 2. Overall, out of the 19 matched metastatic deposits pertaining to this group, 16 (84%) were PD-L1 negative. The three PD-L1 positive metastatic lesions included one loco-regional lymphnode metastasis, one myocardial and one adrenal deposit and had a median histoscore of 50 (range 30–90). Of the 57 PD-L1 negative NSCLC (88%), only one case of SCC had discordant PD-L1 positive lymphnode metastasis. Representative sections showing the heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression in primary and metastatic lesions are shown in Fig. 3.

Table 2.

Intra-tumor heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression in metastatic deposits originating from PD-L1 positive primary NSCLC.

| ID | PD-L1 primary tumor histoscore | Age | Gender | Histology | LN metastasis | Liver metastasis | Adrenal metastasis | Brain metastasis | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15 | 86 | M | Adenocarcinoma | — | — | positive (70) | — | negative (pancreas) |

| 2 | 40 | 64 | M | Adenocarcinoma | — | — | — | negative | negative (spleen) negative (intestinal wall) |

| 3 | 40 | 56 | F | Adenocarcinoma | negative | — | negative | negative | negative (kidney) negative (skeletal muscle) |

| 4 | 40 | 74 | M | Adenocarcinoma | negative | negative | — | — | — |

| 5 | 60 | 74 | M | Squamous cell | positive (50) | negative | — | — | — |

| 6 | 90 | 86 | M | Squamous cell | negative | — | — | — | — |

| 7 | 150 | 63 | M | Adenocarcinoma | — | — | negative | negative | negative (thyroid) positive (30) (heart) |

| 8 | 180 | 76 | M | Squamous cell | — | negative | — | — | — |

Figure 3.

Representative sections at 100× magnification showing a case of PD-L1 positive primary lung adenocarcinoma (Case ID nr. 7, Panel A) with a matched, concordant PD-L1 positive metastatic deposit to the myocardium (Panel B) and a second discordant PD-L1 negative metastatic deposit to the thyroid (Panel C). Panel (D)shows the only identified case of a PD-L1 negative primary adenocarcinoma with evidence of a PD-L1 positive lymphnode metastatic deposit (Panel E). Both specimens show anthracotic pigmentation, more prominent in Panel E. Panel (F)illustrates a PD-L1 positive squamous cell carcinoma (Case ID nr. 5) with evidence of a peritumoral lymphocytic infiltrate and a paired PD-L1 positive lymphnode metastasis shown at 100 × and 400 × magnification (Panel G, H).

Among the 29 primary SCLC and four atypical carcinoids (AC), no PD-L1 expression was documented, with universal concordance between primary and metastatic deposits.

We found positive PD-L2 immunostaining in 11 primary NSCLC (17%). Median histoscore was 40 (range 15–70). Out of the 27 matching metastatic deposits, one splenic, one liver and one adrenal deposits (11%) stained positively for PD-L2 (median histoscore 90, range 80–300), confirming discordant expression in the remaining 24 paired metastases (87%). Out of the 46 metastatic deposits matched to the remaining 54 PD-L2 negative primary NSCLC (83%), four (9%) were PD-L2 positive including two adrenal, one renal and one splenic deposit (median histoscore 75, range 50–270), while the remaining 42 (91%) were concordant to PD-L2 negative primaries.

Two primary SCLC (7%) and one AC (25%) stained positively for PD-L2, with a median histoscore of 180 (range 90–270). Paired metastatic deposits (n = 5) including two liver, two thoracic lymphnode and one pancreatic metastases were all negative for PD-L2 expression. Equally, the remaining 59 metastatic deposits matched to PD-L2 negative primaries were all negative for PD-L2 expression.

We found co-expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 in two primary NSCLCs: one SCC with a histoscore of 40 and 15 for PD-L1 and two and one adenocarcinoma with histoscores of 60 and 50, respectively. Co-immunoexpression was not preserved in the paired metastases: one SCC lymphnode deposit was the sole PD-L1 positive metastatic lesion, displaying PD-L2 negative immunostaining. All remaining metastatic deposits in these two cases (n = 4) were negative for both markers.

When explored for clinicopathologic significance, we found no correlation between the expression of PD ligands in the primary tumor and stage, age or number of metastases in either NSCLC or SCLC cases.

Validation of TMA immunostaining for PD-L1

Due to focal nature of PD-L1 expression and the potential for TMA technique to have introduced selection bias in the assessment of PD-L1 status, we validated our IHC findings on full-faced diagnostic tissue sections in a subgroup of 20 samples. These included the entirety of primary NSCLCs displaying positive PD-L1 immunoexpression (n = 8) and a total of further 12 blocks selected randomly from PD-L1 negative primaries (n = 6) and metastases (n = 6). All the 20 slides were processed in a single batch. In this analysis, we report full concordance between the TMA cores and matched diagnostic sections from donor blocks.

Discussion

Despite notable advancements in the systemic management of the disease, patients with LC who either present with or relapse with distant metastases have got 95% probability to succumb from their disease within 5 y.14

Immunotherapy has emerged as a novel treatment modality in NSCLC, where the PD-1 receptor–ligand signaling stands a nodal point of antitumor immune control. Despite several technical and biologic constraints, IHC detection of PD-L1 has been increasingly utilized as a predictive marker to optimize the selection of patients for immune-checkpoint inhibitors.

A recent meta-analysis of 1,417 NSCLC patients treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies has shown a 29% objective response rate in PD-L1 positive non-squamous patients compared to 11% in PD-L1 negative counterparts; a difference that is not replicated in squamous NSCLC, where PD-L1 status lacks predictive value.15

The expression of PD-1 ligands varies in primary and metastatic melanoma9 and renal cell carcinoma8 and recent studies in multifocal LC yielded similar findings.7 We took this observation forward and utilized a well-annotated and thoroughly quality-controlled autoptic case series of untreated patients to explore the biologic heterogeneity of PD-1 ligands expression in the metastatic progression of the major histotypes of LC.

Using clinically validated cut-off values for PD-L1 expression, we found significant immunopositivity in 12% of the primary NSCLC and in none of the examined SCLC cases. Interestingly, we found a high rate of discordance (>80%) between primary and metastatic NSCLC deposits when the primary tumor was positive for PD-L1 staining, but not in cases with a PD-L1 negative primary, where the only discordant case related to a locoregional lymphnode metastasis. The same observation did not prove true for SCLC, where we found universal PD-L1 negative staining across primary and metastatic disease.11 This suggests that PD-L1 expression may vary in the process of metastatic dissemination of NSCLC but not SCLC, where lack of PD-L1 expression appears to be a preserved trait. Interestingly, PD-L2 expression followed a similar trend to PD-L1, where nearly 90% of the paired metastatic deposits showed discordance in PD-L2 status compared to positive primary tumors. Unlike PD-L1 expression, the discordance in PD-L2 positivity was not unique to NSCLC but extended to SCLC and AC primaries, whose metastases were universally PD-L2 negative.

Overall, our results confirm the differential regulation of PD ligands emerged in previous studies in LC where positivity to either marker ranged between 25 and 50%,10 being highest in non-squamous histology.16,17

There are a number of reasons that may justify the differential expression of PD ligands we observed and therefore potentially influence the performance of PD-L1 as a stratifying biomarker in the clinic. First, unlike other molecular traits, PD-L1 expression appears to be a dynamic rather than a constitutive molecular event in most solid tumors. Many factors have been shown to influence PD-L1 expression including tumor hypoxia, a pro-inflammatory, interferon-gamma rich microenvironment as well as activation of numerous intracellular pathways that promote cell motility and survival including phosphatydil-inositol-3-kinase/AKT and the Ras-Raf-Erk pathways.18 Given the central role that the dysregulation of these mechanisms carries in the metastatic process of LC, we postulate whether the discordance in PD ligands expression between primary tumors and metastases might be driven by the differing gene expression profiles within each metastatic site and their respective microenvironment19 ultimately resulting in a broader heterogeneity of the antitumor immune-control mechanisms.20

While the biologic mechanisms governing PD-L1 expression in LC deserve full mechanistic elucidation, our findings raise the possibility that the intra-tumor heterogeneity in the expression of PD-L1 might lead to inaccuracy in the assessment of patients' PD-L1 status, hence contributing to the observed clinical diversity in the response rates to immune-checkpoint inhibitors despite PD-L1 IHC-based stratification. It is unknown whether PD-L1 expression across all disease sites is a pre-requisite for immune clearance by T cells following stimulation with anti-PD1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade. Results from prospective trials in LC have shown evidence of enhanced immune responses with values of PD-L1 immunopositivity as low as 1%.21 These studies however included a mixture of archival and newly sampled tumor specimens, which might have introduced even greater heterogeneity in assigning PD-L1 status. In our study, we utilized a more conservative cut-off value of 5% due to a more robust relationship with clinical outcomes in prospective trials22 as well as to mitigate the concerns over the reproducibility and generalizability of lower threshold for positivity.23

Independent from the pre-defined threshold utilized for patient stratification, our study adds a further layer of complexity to already problematic clinical reproducibility of PD-L1 immunostaining as a clinical biomarker. Due to the focal expression of PD-L1, it is conceivable that the use of low thresholds for positivity may have led to potentially underestimate the proportion of PDL-1 positive patients, more so in light of our findings where the high rates of PD-L1 negative metastatic deposits may not represent matching PD-L1 positive primary counterparts.

A limitation of our study is that of having appraised intra-tumor heterogeneity in PD ligands expression as a unidimensional feature of the disease, having evaluated the phenotypic diversity of primary LC and synchronous metastases at the time of patient's death. The plasticity of clonal evolution of LC over time and as a function of treatment cannot be inferred from our data and it would be important to validate our findings in a prospective collection of paired primary and metachronous metastases.24 Equally, we did not address the relationship between PD ligands expression and the status of oncogenic drivers of LC progression, a point that would be important to evaluate in future studies.5

To conclude, our study demonstrates significant heterogeneity in the distribution of PD-L1 expression in NSCLC but not in SCLC, while PD-L2 expression showed similar heterogeneity across both NSCLC and SCLC. Our data suggest differential regulation of immune-tolerance pathways in the metastatic progression of LC, which may hold important clinical implications in the optimal provision of immunotherapy. Studies are underway to discover whether such differential positivity results from clonal divergence in the genomic drivers of LC progression.25

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust Tissue Bank for having supported the study. DJP is supported by grant funding from the NIHR, Action Against Cancer, the Academy of Medical Sciences and the Imperial BRC.

References

- 1.Rizvi NA, Mazieres J, Planchard D, Stinchcombe TE, Dy GK, Antonia SJ, Horn L, Lena H, Minenza E, Mennecier B et al.. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16:257-65; PMID:25704439; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70054-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crino L, Eberhardt WE, Poddubskaya E, Antonia S, Pluzanski A, Vokes EE, Holgado E et al.. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:123-35; PMID:26028407; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anagnostou VK, Brahmer JR. Cancer immunotherapy: a future paradigm shift in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21:976-84; PMID:25733707; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, Powderly JD, Picus J, Sharfman WH, Stankevich E, Pons A, Salay TM, McMiller TL et al.. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28:3167-75; PMID:20516446; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel SP, Kurzrock R. PD-L1 Expression as a Predictive Biomarker in Cancer Immunotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther 2015; 14:847-56; PMID:25695955; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ilie M, Hofman V, Dietel M, Soria JC, Hofman P. Assessment of the PD-L1 status by immunohistochemistry: challenges and perspectives for therapeutic strategies in lung cancer patients. Virchows Arch 2016; 468(5):511-25; PMID:26915032; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00428-016-1910-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mansfield AS, Murphy SJ, Peikert T, Yi ES, Vasmatzis G, Wigle DA, Aubry MC. Heterogeneity of Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 Expression in Multifocal Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 22(9):2177-82; PMID:26667490; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callea M, Albiges L, Gupta M, Cheng SC, Genega EM, Fay AP, Song J, Carvo I, Bhatt RS, Atkins MB et al.. Differential Expression of PD-L1 between Primary and Metastatic Sites in Clear-Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res 2015; 3:1158-64; PMID:26014095; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madore J, Vilain RE, Menzies AM, Kakavand H, Wilmott JS, Hyman J, Yearley JH, Kefford RF, Thompson JF, Long GV et al.. PD-L1 expression in melanoma shows marked heterogeneity within and between patients: implications for anti-PD-1/PD-L1 clinical trials. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2015; 28:245-53; PMID:25477049; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/pcmr.12340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim MY, Koh J, Kim S, Go H, Jeon YK, Chung DH. Clinicopathological analysis of PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression in pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma: Comparison with tumor-infiltrating T cells and the status of oncogenic drivers. Lung Cancer 2015; 88:24-33; PMID:25662388; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schultheis AM, Scheel AH, Ozretic L, George J, Thomas RK, Hagemann T, Zander T, Wolf J, Buettner R. PD-L1 expression in small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas. Eur J Cancer 2015; 51:421-6; PMID:25582496; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheng J, Fang W, Yu J, Chen N, Zhan J, Ma Y, Yang Y, Yanhuang, Zhao H, Zhang L. Expression of programmed death ligand-1 on tumor cells varies pre and post chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep 2016; 6:20090; PMID:26822379; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/srep20090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinato DJ, Tan TM, Toussi ST, Ramachandran R, Martin N, Meeran K, Ngo N, Dina R, Sharma R. An expression signature of the angiogenic response in gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours: correlation with tumour phenotype and survival outcomes. Br J Cancer 2014; 110:115-22; PMID:24231952; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/bjc.2013.682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fry WA, Phillips JL, Menck HR. Ten-year survey of lung cancer treatment and survival in hospitals in the United States: a national cancer data base report. Cancer 1999; 86:1867-76; PMID:10547562; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19991101)86:9%3c1867::AID-CNCR31%3e3.0.CO;2-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gandini S, Massi D, Mandala M. PD-L1 expression in cancer patients receiving anti PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2016 Apr; 100:88-98; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tokito T, Azuma K, Kawahara A, Ishii H, Yamada K, Matsuo N, Kinoshita T, Mizukami N, Ono H, Kage M et al.. Predictive relevance of PD-L1 expression combined with CD8+ TIL density in stage III non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Eur J Cancer 2016; 55:7-14; PMID:26771872; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konishi J, Yamazaki K, Azuma M, Kinoshita I, Dosaka-Akita H, Nishimura M. B7-H1 expression on non-small cell lung cancer cells and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and their PD-1 expression. Clin Cancer Res 2004; 10:5094-100; PMID:15297412; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J, Jiang CC, Jin L, Zhang XD. Regulation of PD-L1: a novel role of pro-survival signalling in cancer. Ann Oncol 2016 Mar; 27(3):409-16; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/annonc/mdv615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lou Y, Diao L, Parra Cuentas ER, Denning WL, Chen L, Fan YH et al.. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition is associated with a distinct tumor microenvironment including elevation of inflammatory signals and multiple immune checkpoints in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2016 Jul 15; 22(14):3630-42; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alsuliman A, Colak D, Al-Harazi O, Fitwi H, Tulbah A, Al-Tweigeri T, Al-Alwan M, Ghebeh H. Bidirectional crosstalk between PD-L1 expression and epithelial to mesenchymal transition: significance in claudin-low breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer 2015; 14:149; PMID:26245467; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/s12943-015-0421-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E et al.. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1627-39; PMID:26412456; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gettinger SN, Horn L, Gandhi L, Spigel DR, Antonia SJ, Rizvi NA, Powderly JD, Heist RS, Carvajal RD, Jackman DM et al.. Overall Survival and Long-Term Safety of Nivolumab (Anti-Programmed Death 1 Antibody, BMS-936558, ONO-4538) in Patients With Previously Treated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33:2004-12; PMID:25897158; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shukuya T, Carbone DP. Predictive Markers for the Efficacy of Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 Antibodies in Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016; 11:976-88; PMID:26944305; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alizadeh AA, Aranda V, Bardelli A, Blanpain C, Bock C, Borowski C, Caldas C, Califano A, Doherty M, Elsner M et al.. Toward understanding and exploiting tumor heterogeneity. Nat Med 2015; 21:846-53; PMID:26248267; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.3915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGranahan N, Furness AJ, Rosenthal R, Ramskov S, Lyngaa R, Saini SK, Jamal-Hanjani M, Wilson GA, Birkbak NJ, Hiley CT et al.. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science 2016; 351:1463-9; PMID:26940869; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.aaf1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]