Summary

Following implantation, mouse epiblast cells transit from a naïve to a primed state in which they are competent for both somatic and primordial germ cell (PGC) specification. Using mouse embryonic stem cells (mESC) as an in vitro model to study the transcriptional regulatory principles orchestrating peri-implantation development, here we show that the transcription factor Foxd3 is necessary for exit from naïve pluripotency and progression to a primed pluripotent state. During this transition, Foxd3 acts as a repressor that dismantles a significant fraction of the naïve pluripotency expression program through decommissioning of active enhancers associated with key naïve pluripotency and early germline genes. Subsequently, Foxd3 needs to be silenced in primed pluripotent cells to allow reactivation of relevant genes required for proper PGC specification. Our findings therefore uncover a cycle of activation and deactivation of Foxd3 required for exit from naïve pluripotency and subsequent PGC specification.

Introduction

Mouse peri-implantation development (E4.5-E7.5) is characterized by dynamic cellular transitions that involve major switches in transcriptional and epigenetic programs, resulting in the activation and repression of numerous genes and regulatory elements (Buecker et al., 2014; Hayashi et al., 2011; Kurimoto et al., 2015). Pre-implantation epiblast (E4.5) cells can give rise to all embryonic lineages, including the germline, and are considered to display a naïve or ground pluripotent state (Hackett and Surani, 2014; Leitch and Smith, 2013). Upon implantation, epiblast cells transit to a primed state (E5.5-7.5), characterized by a partial extinction of the naïve pluripotency program and the incipient expression of somatic germ layer specifiers (Kalkan and Smith, 2014). While most of the post-implantation epiblast progresses towards somatic differentiation, a few cells in its proximal-posterior end undergo major reprogramming events, leading to PGC specification (~E6-6.5) (Hayashi et al., 2011; Ohinata et al., 2009) and re-activation of naïve pluripotency genes (Hayashi et al., 2011; Yamaji et al., 2008, 2013).

Mouse peri-implantation development is difficult to study in vivo due to the scarcity and transient nature of the involved cell populations. This can be overcome by using mESC grown under different growth-factor conditions as in vitro models (Hackett and Surani, 2014; Kalkan and Smith, 2014). Under “serum+LIF” (SL), mESC display heterogeneity and metastability, with a majority of cells residing in a naïve state that can reversibly switch to a primed one. The naïve state can be more faithfully recapitulated by growing mESC under “2i+LIF” (Ying et al., 2008). Primed pluripotency is represented in vitro by epiblast-like cells (EpiLC) and epiblast stem cells (EpiSC), which resemble the pre-gastrulating and gastrulating post-implantation epiblast, respectively (Hayashi et al., 2011; Kojima et al., 2014). Moreover, primordial germ cell-like cells (PGCLC) can be induced from EpiLC, opening the possibility to investigate the transcriptional and epigenetic changes underlying PGC specification (Hayashi et al., 2011).

The transcriptional regulatory network that maintains the ground pluripotent state consists of a set of “core” (Oct4/Pou5f1, Sox2) and “ancillary” (Esrrb, Nanog, Tbx3, Prdm14) TFs that cooperatively establish a broad set of enhancers (Chen et al., 2008; Dunn et al., 2014; Hackett and Surani, 2014; Marson et al., 2008). The progression from naïve to primed pluripotency involves and likely requires the dismantling of the naïve gene expression program (Kalkan and Smith, 2014). However, the repressors mediating this gene silencing process remain poorly characterized. One potential candidate is Foxd3, a member of the forkhead family of TFs required to maintain pluripotency both in vivo and in vitro (Hanna et al., 2002; Liu and Labosky, 2008) that has been suggested to preferentially act as a repressor (Yaklichkin et al., 2007). Foxd3−/− pre-implantation embryos appear morphologically normal, but die soon after implantation due to a loss of epiblast cells (Hanna et al., 2002), suggesting that Foxd3 might be most critical during the progression from naïve to primed pluripotency. Here we show that Foxd3 dismantles a significant fraction of the naïve expression program through the decommissioning of active enhancers, thus being required to exit naïve pluripotency and to reach the primed pluripotent state. Subsequently, Foxd3 needs to be silenced in EpiLC in order to efficiently differentiate these cells into PGCLC, therefore uncovering de-repression as an important regulatory mechanism during the acquisition of germline identity.

Results

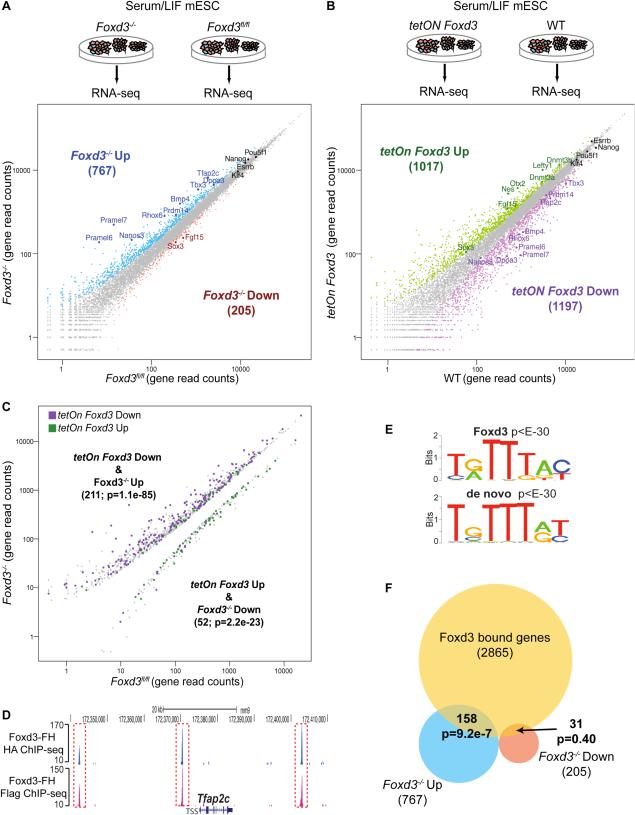

Foxd3 acts mostly as a repressor in mESC

In order to uncover genes regulated by Foxd3 in mESC, we performed gain and loss of function experiments in cells grown under SL conditions. First, we used a previously established mESC line (i.e. Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER) in which Foxd3 can be deleted upon tamoxifen (TM) treatment (Figure S1A-B) (Liu and Labosky, 2008) to identify, by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), genes misexpressed upon loss of Foxd3 (Figure 1A). We observed that Foxd3 repressed almost four-times as many genes as it activated (767 upregulated vs 205 downregulated genes) (Data S1). In addition, we generated a mESC line (i.e. tetOn Foxd3) in which Foxd3 can be overexpressed in a doxycycline (Dox) inducible manner (Figure S1C-D). Using RNA-seq, we observed similar number of genes being repressed or activated by Foxd3 overexpression (1197 downregulated vs 1017 upregulated genes) (Figure 1B) (Data S1). However, the concordance between the expression changes elicited by either loss or overexpression of Foxd3 was especially significant among genes repressed by Foxd3 (p=8.1e-85) (Figure 1C, Figure S1E). RNA-seq results were validated by RT-qPCR (Figure S1F-G) and by the significant overlaps observed between genes found as misexpressed in our and previous studies in Foxd3−/− and Foxd3 overexpressing mESC (Figure S1H-I).

Figure 1. Foxd3 acts mostly as a transcriptional repressor in mESC.

(A) RNA-seq experiments in Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER mESC treated with TM for three days (Foxd3−/−) or left untreated (Foxd3fl/fl). Mouse genes were plotted according to average normalized RNA-seq read counts in Foxd3−/− and Foxd3fl/fl cells. (B) RNA-seq experiments in tetON Foxd3 and WT mESC treated with Dox for three days. (C) Mouse genes considered as differentially expressed in Foxd3−/− mESC are plotted according to the RNA-seq read counts in Foxd3−/− and Foxd3fl/fl mESC and color-coded according to expression changes in tetON Foxd3 cells (purple for downregulated genes; green for upregulated genes). (D) ChIP-seq profiles generated in Foxd3-FH mESC with anti-HA and anti-Flag antibodies around a representative locus (i.e. Tfap2c). (E) Overrepresented gmotifs enriched at Foxd3-bound regions based on matches to known TF consensus binding sequences (top) or through de novo motif analysis (bottom). (F) Venn-diagram representing the overlaps between genes bound by Foxd3 and genes considered as either up or downregulated in Foxd3−/− mESC. P-values in (C) and (F) were calculated using hypergeometric tests. See also Figure S1, Data S1-2.

To further investigate if, as the previous results suggest, Foxd3 acts mostly as a repressor in mESC, we used chromatin immunoprecipiation sequencing (ChIP-seq) to globally map Foxd3 genomic occupancy. Due to the lack of commercial antibodies suitable for ChIP (Supplemental Experimental Procedures), we generated a mESC line constitutively expressing Flag-HA tagged Foxd3 (i.e FH-Foxd3) at nearly endogenous levels (Figure S1J-K). ChIP-seq using anti-HA and anti-Flag antibodies resulted in the identification of 2496 genomic regions considered as bound by Foxd3 in both ChIP-seq experiments (Figure 1D, Figure S1L, Data S2). ChIP-seq specificity was validated (Figure S1M-N) and highlighted by the significant overrepresentation of the Foxd3 consensus binding sequence among the identified Foxd3-bound genomic regions (Figure 1E). The 2496 Foxd3-bound regions were assigned to 2865 nearby genes using GREAT (McLean et al., 2010) (Data S2). To confirm the validity of these assignments, we used mESC topological associating domain (TADs) maps and found that ~90% of the Foxd3-bound regions and their associated genes were within the same TAD (Dixon et al., 2012). Importantly, genes repressed by Foxd3 but not activated ones, were bound by Foxd3 significantly more than expected by chance (p=9.2e-7 vs p=0.40) (Figure 1F). Our results indicate that, in SL mESC, Foxd3 preferentially represses its target genes and that gene activation might be due to secondary indirect effects.

Foxd3 represses a considerable fraction of the naïve pluripotency expression program

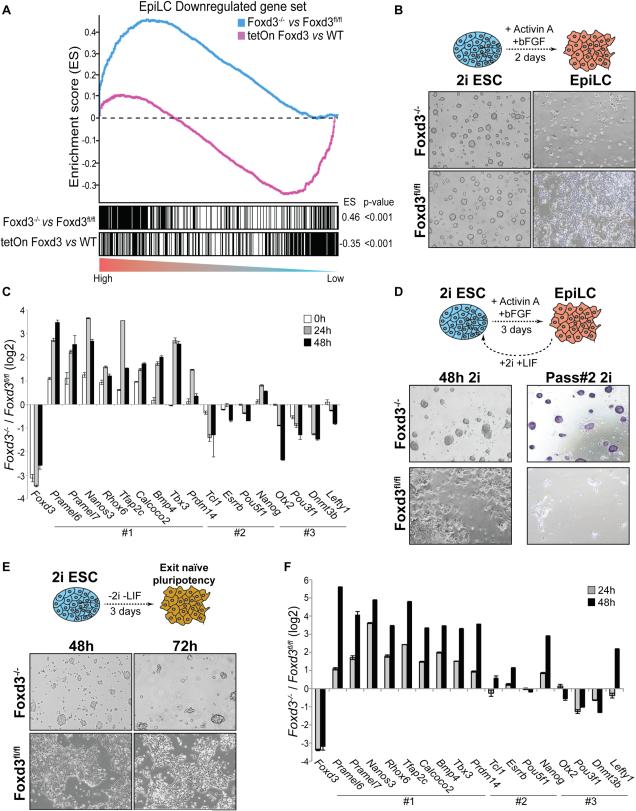

Manual inspection of genes repressed by Foxd3 revealed several naïve pluripotency regulators preferentially expressed in the pre-implantation epiblast (e.g. Dppa3, Tbx3, Prdm14, Pramel6/7) (Hayashi et al., 2011). Furthermore, Foxd3 did not affect the expression of neither core pluripotency TFs (e.g. Oct4, Sox2) nor of all naïve pluripotency genes (e.g. Nanog, Esrrb, Klf4) (Figure 1A-B, Figure S1F-G). To investigate if Foxd3 had a similar regulatory role when mESC were maintained under naïve conditions, we performed RNA-seq in mESC adapted to “2i+LIF” (Data S1). Overall, there were significant similarities between the expression changes occurring upon loss of Foxd3 in mESC grown under SL and 2i (Figure S2A-B). Moreover, under 2i, Foxd3 also preferentially acted as a transcriptional repressor (Figure S2C). These preliminary observations suggest that Foxd3 could promote the exit from naïve pluripotency through the direct repression of key naïve pluripotency regulators. To substantiate this hypothesis, we used available transcriptome profiles generated during the differentiation of 2i ESC towards EpiLC (Hayashi et al., 2011). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) showed that the set of genes most significantly downregulated during the transition from 2i ESC to EpiLC was globally repressed by Foxd3 in SL and 2i mESC (Figure 2A, Figure S2D-E, Table S1, Table S2), while genes upregulated during such transition were globally induced (Figure S2F, Table S1). Similar correlations were observed when Foxd3 target genes were compared with those genes that changed their expression between 2i ESC and the pre-gastrulating mouse epiblast (Table S1) (Hayashi et al., 2011). Moreover, Foxd3 was significantly upregulated in EpiLC and the pre-gastrulating epiblast compared to 2i ESC (Hayashi et al., 2011)(Figure S3A).

Figure 2. Foxd3 is required for the exit from naïve pluripotency.

(A) GSEA for the 500 most downregulated genes during the differentiation of 2i ESC into EpiLC (Hayashi et al., 2011) with respect to the global transcriptional changes observed in Foxd3−/− Vs Foxd3fl/fl or tetON Foxd3 Vs WT mESC. ES: enrichment score. (B) Brightfield images are shown for: Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER cells adapted to 2i+LIF conditions (2i ESC) and then treated with TM for three days (Foxd3−/−) or left untreated (Foxd3fl/fl) (left panels); Foxd3−/− and Foxd3fl/fl cells after differentiation into EpiLC (right panels). (C) Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER 2i ESC were treated as in (B) and transcriptional changes between Foxd3−/ and Foxd3fl/fl cells during differentiation into EpiLC are presented in log2 scale. #1: naïve pluripotency and early germline genes repressed by Foxd3 according to RNA-seq data in Foxd3−/− mESC; #2 pluripotency genes not repressed by Foxd3 and #3: primed pluripotency genes. (D) Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER 2i ESC were treated with TM or left untreated, differentiated into EpiLC for three days and then re-plated under “2i+LIF”. Left panels show Foxd3−/− and Foxd3fl/fl cells after 48 hours of being re-plated in “2i+LIF”. The Right panel shows alkaline phosphatase staining of Foxd3−/− and Foxd3fl/fl cells after two passages in “2i+LIF”. (E) Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER 2i ESC were pre-treated with TM for 12 hours (Foxd3−/−) or left untreated (Foxd3fl/fl) and then released from 2i+LIF for 48 (left panels) or 72 hours (right panels). TM was maintained during differentiation. (F) Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER 2i ESC were treated as in (E) and transcriptional changes between Foxd3−/ and Foxd3fl/fl after release from “2i+LIF” are presented in log2 scale. See also Figures S2-3, Tables S1-2.

Foxd3 is necessary for the exit from naïve pluripotency

In order to directly address if Foxd3 plays a central role during the exit from naïve pluripotency, we adapted Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER; cells to “2i+LIF”, treated them with TM for three days and then performed the differentiation towards EpiLCs. Compared to untreated cells, which after two days displayed the typical morphological features of EpiLC (Buecker et al., 2014; Hayashi et al., 2011) and the expected changes in gene expression (Figure S3A), the majority of Foxd3−/− cells were not able to make such transition, failed to attach to the tissue culture plate and died (Figure 2B, ~90% dead cells based on trypan blue staining). Nevertheless, we collected the few Foxd3−/− cells that remained attached after EpiLC differentiation and evaluated the expression of a panel of relevant genes (Figure 2C). Foxd3−/− cells were unable to silence naïve genes representing direct Foxd3 targets (e.g. Tbx3, Prdm14, Tfap2c, Pramel6/7), while other naïve and core pluripotency regulators showed normal expression dynamics (e.g. Esrrb, Nanog, Pou5f1). Moreover, Foxd3−/− cells failed to upregulate early post-implantation gene markers (e.g. Dntm3b, Otx2, Pou3f1) (Figure 2C). To test if the failure of Foxd3−/− cells to differentiate into EpiLC could be the result of an initially abnormal state, we repeated the previous experiments with Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER cells pre-treated with TM for only 12 hours (Figure S3B). Under these conditions, the expression of most analysed genes was barely changed when differentiation was started (0h) (Figure S3C). Nevertheless, after two days, most TM-treated cells either died or failed to acquire EpiLC morphological and molecular features (Figure S3B-C). The specificity of the phenotypic defects observed in Foxd3−/− cells was confirmed by performing experiments in which transient overexpression of Foxd3 in these cells significantly restored their differentiation potential (Figure S3D). The extensive cell death observed in Foxd3−/− mESC upon EpiLC differentiation could indicate that, in addition to the silencing of naïve pluripotency genes, a major role of Foxd3 during this cellular transition could be to increase cell survival in primed pluripotent cells, which are characterized by a low apoptotic threshold (Pernaute et al., 2014). In agreement with this, Gene Ontology analysis of genes upregulated in Foxd3−/− mESC revealed a significant overrepresentation of pro-apoptotic genes (Figure S3E). To confirm that Foxd3 contributes to the exit from naïve pluripotency through repression of the naïve pluripotency expression program, we performed commitment assays in which Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER 2i mESC treated with TM were differentiated towards EpiLCs and then re-plated into “2i+LIF” (Figure 2D). EpiLC differentiation was extended to three days, since by this time most cells are committed to differentiate and have lost their naïve pluripotency properties (Leeb et al., 2014). Foxd3fl/fl EpiLC could not be re-adapted to “2i+LIF” condition as they either died or appeared differentiated after 48 hours (Figure 2D) and formed, almost exclusively, differentiated alkaline-phosphatase negative colonies upon passaging. In stark contrast, the surviving Foxd3−/− cells generated mostly naïve-like colonies after being re-plated into “2i+LIF”, were able to proliferate, could be maintained for at least 2-3 passages and formed alkaline-phosphatase positive colonies (Figure 2D, Figure S3F).

The transition from 2i ESC into EpiLC involves passaging and a change in growth factor and substrate conditions. Since all these factors could contribute to the incapacity of Foxd3−/− cells to exit the naïve state, we treated Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER cells with TM for three days and then induced the exit from naïve pluripotency by simply removing LIF and 2i inhibitors (Betschinger et al., 2013; Leeb et al., 2014). Similarly to EpiLC differentiation, Foxd3 was rapidly upregulated upon release from “2i+LIF” (Figure S3G). Within 24 hours, a large fraction of Foxd3−/− cells appeared as floating dying cells (~90% dead cells based on trypan blue staining). Those that remained attached did not show morphological or molecular features indicative of an exit from naïve pluripotency (Figure S3H-I). The previous experiments were then repeated using Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER cells treated with TM for 12 hours before the release from “2i+LIF”. Based on trypan blue staining, ~30% and ~50% of Foxd3−/− cells died 24 and 48 hours after the release from “2i+LIF”, respectively. Although cell death was higher than in untreated Foxd3fl/fl cells (~10% and ~15% dead cells 24 and 48 hours after the release from “2i+LIF”), it was nevertheless considerably lower than the ~90% dead cells observed 24 hours after the release from “2i+LIF” when cells were pre-treated with TM for three days. Thus, following a short pre-treatment with TM, cell survival and the exit from naïve pluripotency became temporally decoupled, as cell death was reduced during the first 48 hours after the release from “2i+LIF”, only becoming conspicuous again after 72 hours (Figure 2E). After 48 hours, Foxd3−/− cells formed naïve-like colonies (Figure 2E) and expressed naïve pluripotency regulators at higher levels than untreated controls (Figure 2F).

When overexpressed in SL mESC, Foxd3 lead not only to the repression of naïve pluripotency genes, but also to the induction of primed pluripotency ones (Figure 1B), suggesting that Foxd3 overexpression could be sufficient to drive mESC out of the naïve pluripotent state. However, Foxd3 overexpression in tetOn Foxd3 cells adapted to “2i+LIF” did not result in any evident morphological changes (data not shown), indicating that additional intrinsic and/or extrinsic regulatory factors are required for the transition to a primed pluripotent state. To further explore this idea, tetOn Foxd3 cells were cultured in “2i+LIF” medium supplemented with serum (Figure S3J). Under these conditions, Foxd3 overexpression resulted in phenotypic and molecular changes suggestive of a transition to a primed-like pluripotent state, including repression of naïve pluripotency genes and increased expression of several, but not all, primed pluripotency markers (e.g. Dnmt3b, Lefty1, Nes) (Figure S3J-K). Overall, our results suggest that Foxd3 provides a permissive state, characterized by the dismantling of the naïve pluripotency expression program, in which other intrinsic (e.g. Otx2) and extrinsic factors (e.g. Fgf/Erk, Activin/Nodal) with instructive regulatory functions can promote the transition to primed pluripotency (Betschinger et al., 2013; Buecker et al., 2014; Kalkan and Smith, 2014).

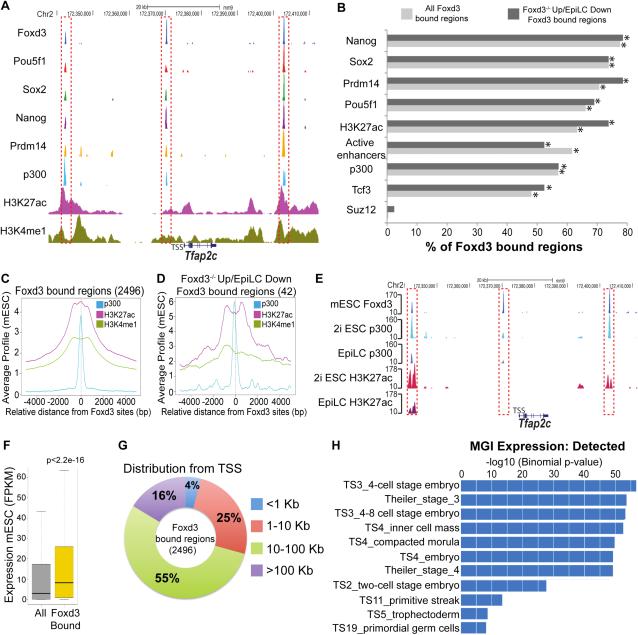

Foxd3 binds to active enhancers in mESC

To get insights into the mechanistic basis of Foxd3 repressive function, Foxd3 genomic targets were compared with the binding profiles of several TFs and histone modifications in SL and 2i mESC (Figure 3A-E) (Buecker et al., 2014; Creyghton et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2011; Marson et al., 2008; Wamstad et al., 2012). Foxd3 bound regions displayed chromatin features typical of active enhancers in both SL (Figure 3A-D) and 2i mESC (Figure 3E). Indeed, more than 60% of all Foxd3 bound regions overlapped previously defined active enhancers in mESC (p<0.0001) and 51% (119/231) of mESC super-enhancers were bound by Foxd3 (Whyte et al., 2013). The active enhancer identity of Foxd3 bound regions was supported by their distal location with respect to gene transcription start sites (TSSs), the high expression levels of their nearest genes and their significant association with genes expressed and functionally involved in mouse pre-implantation development (Figure 3F-H).

Figure 3. Foxd3 preferentially binds to active enhancers in mESC.

(A) ChIP-seq profiles for the indicated proteins around a representative locus (i.e. Tfap2c). (B) Percentage of Foxd3−/− Up/EpiLC Down (Foxd3 bound regions associated with genes upregulated in Foxd3−/− mESC and downregulated during the differentiation of 2i ESC into EpiLC) and of all Foxd3 bound regions that are also bound by the indicated proteins. * statistically significant (p>0.0001) overlap. (C-D) Average ChIP-seq profiles for p300, H3K27ac and H3K4me1 in mESC around the central position of (C) all Foxd3 bound regions and (D) Foxd3−/− Up/EpiLC Down regions. (E) ChIP-seq profiles for Foxd3 in SL mESC and for p300 and H3K27ac in both 2i ESC and EpiLC around a representative locus (i.e. Tfap2c). (F) Expression levels measured as FPKMs (fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped) for all mouse genes or for genes considered as bound by Foxd3. P-value calculated using a non-paired Wilcoxon test. (G) Distances between Foxd3 bound regions and their closest ENSEMBL gene TSSs. (H) Functional annotation of Foxd3 bound regions according to GREAT analysis.

Foxd3 mediates the decommissioning of naïve pluripotency enhancers

We hypothesized that Foxd3 could facilitate the exit from naïve pluripotency by mediating the decommissioning of enhancers required for the expression of naïve pluripotency genes. To start investigating this possibility, we first used publically available data to analyse enhancer chromatin features around Foxd3 bound regions during the differentiation of 2i ESC into EpiLC (Buecker et al., 2014). In contrast to either all Foxd3 or all Oct4 genomic targets, which showed moderate enhancer chromatin changes (Figure 4A), Foxd3−/− Up/EpiLC Down regions displayed a striking loss of p300 and H3K27ac, two major marks associated with active enhancers (Figure 3E, Figure 4A, Figure S4A-C), and a less pronounced change in Oct4 binding (Figure S4D). On the other hand, H3K4me1, which does not correlate with the regulatory activity of enhancers (Bonn et al., 2012; Creyghton et al., 2010; Rada-Iglesias et al., 2011), remained relatively constant (Figure S4D). Although the lack of antibodies against endogenous Foxd3 precluded a quantitative analysis of Foxd3 binding dynamics during the exit from naïve pluripotency, using FH-Foxd3 cells we confirmed that FH-Foxd3 was able to bind the majority of analyzed naïve pluripotency enhancers in 2i mESC and EpiLC (Figure S4E-G).

Figure 4. Foxd3 mediates the decommissioning of a subset of naïve pluripotency enhancers.

(A) Average p300 and H3K27ac ChIP-seq profiles in 2i ESC and EpiLC are shown around three different subsets of TF bound regions: (i) Foxd3−/− Up/EpiLC Down; (ii) Foxd3 all (all regions bound by Foxd3 in mESC); (iii) Pou5f1 all (all regions bound by Pou5f1/Oct4 in mESC). (B-E) ChIP-qPCR analysis was performed for H3K27ac and H3K4me2 in (B-C) tetON Foxd3 and WT mESC treated with Dox for three days and (D-E) Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER mESC treated with TM for three days (Foxd3−/−) or left untreated (Foxd3fl/fl). ChIP signals were calculated as % of input and then normalized to the average ChIP signals obtained at two intergenic control regions (ctrl1, ctrl2). ChIP signal differences are presented in log2 scale. Foxd3 bound regions are named based on their associated genes and the distance to their TSS in Kb. Nudcd3(+19.5) and Slc25a46(−40.5) correspond to Oct4 bound genomic regions weakly bound by Foxd3 and overlapping enhancers active in both 2i ESC and EpiLC. (F) Reporter cell lines were established for two Foxd3 bound regions (Tbx3 (+9.4) and Nanos3 (−1.1)) in tetON Foxd3 mESC. GFP signals were assayed in cells that were treated with Dox (+Dox) for three days or left untreated (−Dox). (G-H) Transcriptional changes in Foxd3 and GFP levels for Tbx3(+9.4) and Nanos3(−1.1) reporter cell lines generated in tetON Foxd3 (lines #1 and #2) or WT mESC. P-values were calculated using one-tailed t-tests. (I) Changes in eRNA levels between Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER 2i ESC pre-treated with TM for 12 hours (Foxd3−/−) or left untreated (Foxd3fl/fl) before being released from 2i+LIF conditions for 48 hours. eRNA levels were normalized to that of two housekeeping genes (Hprt1 and Eef1a) and measured both upstream (5’, blue) and downstream (3’, red) of the indicated regions. (J) ChIP-qPCR analysis for H3K27ac in Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER treated like in (I). * statistically significant differences (p<0.05; fold-change (FC)>1.5 Up or Down (in log2, FC>0.58 or <-0.58)) in ChIP signals or eRNA levels between cells being compared in each case. P-values calculated using one-tailed t-test. # genomic regions considered as bound by Foxd3 according to HA ChIP-seq and just below the calling cut-off in Flag ChIP-seq (Data S2). See also Figures S4-5.

To test if Foxd3 was indeed able to silence naïve pluripotency enhancers, we evaluated the impact of Foxd3 overexpression on some of these regulatory elements. tetOn Foxd3 mESC were treated with Dox and the levels of various histone modifications (i.e. H3K27ac, H3K27me2, H3K4me1, H3K4me2) at selected enhancers were evaluated by ChIP-qPCR. Compared to control cells, tetOn Foxd3 cells displayed lower levels of H3K27ac and H3K4me2 (active enhancers) (Pekowska et al., 2011; Rada-Iglesias et al., 2011), increased H3K27me2 (inactive enhancers) (Ferrari et al., 2014) and minor changes in H3K4me1 levels (active and inactive enhancers) (Bonn et al., 2012; Buecker et al., 2014; Rada-Iglesias et al., 2011) at most of the analysed naïve enhancers (Figure 4B-C, Figure S5A-B). In addition to their unique chromatin signature, active enhancers produce short bidirectional transcripts termed eRNAs (enhancer RNAs), whose expression strongly correlates with enhancer activity (Andersson et al., 2014). Using RT-qPCR, we found that Foxd3 overexpression significantly reduced eRNA levels at most of the analysed enhancers (Figure S5C). The role of Foxd3 was similarly evaluated using Foxd3−/− mESC, which displayed increased levels of H3K27ac and H3K4me2 (Figure 4D-E) and minor changes in H3K27me2 (Figure S5D) at most of the analysed enhancers. To more directly assess the effect of FOXD3 on enhancer activity, we performed reporter assays in tetON Foxd3 and WT mESC for a couple of naïve pluripotency enhancers bound by Foxd3 (i.e. Tbx3 (+9.4) and Nanos3 (−1.1)). tetON Foxd3 cells treated with Dox displayed significantly reduced GFP levels (Figure 4F-H, Figure S5E), demonstrating that Foxd3 is able to reduce the regulatory activity of naïve pluripotency enhancers.

To test if Foxd3 is required for the decommissioning of enhancers that accompanies the exit from naïve pluripotency, Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER 2i ESC were treated with TM and then differentiated into EpiLC. Using this differentiation protocol, loss of Foxd3 resulted in extensive cell death, precluding the use of ChIP to analyse changes in histone modification levels. However, we reasoned that the number of surviving cells could be enough to measure eRNA levels as a readout of enhancer activity. Importantly, Foxd3−/− cells displayed significantly higher eRNA levels compared to control cells for most of the analysed enhancers (Figure S5F). Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER mESC pre-treated with TM for 12 hours and then released from “2i+LIF” failed to exit the naïve pluripotent state without exhibiting as pronounced cell death (Figure 2E), giving us the opportunity to evaluate changes in histone modification levels. Importantly, most of the investigated enhancers showed increased eRNA, H3K27ac and H3K4me2 levels in Foxd3−/− after the release from “2i+LIF” (Figure 4I-J, Figure S5G).

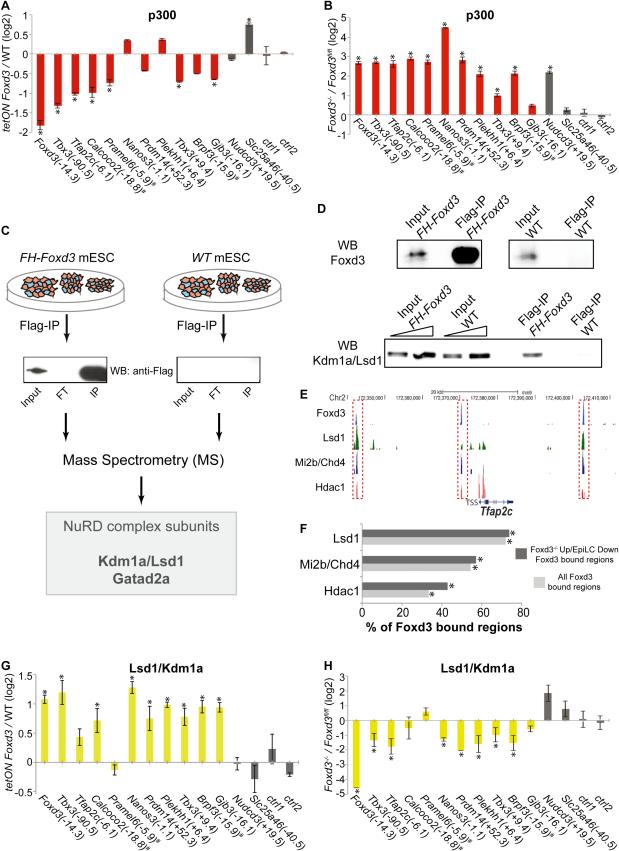

Foxd3 shifts the balance between co-activators and co-repressors to mediate the decommissioning of active enhancers

Enhancers bound by Foxd3 in mESC are also occupied by other TFs (e.g. Oct4, Sox2, Nanog) and co-activators (e.g p300) that promote the active state of these regulatory sequences (Figure 3A-B) (Chen et al., 2008). To investigate if Foxd3 could interfere with the binding of these regulatory proteins, we treated tetON Foxd3 mESC with Dox and then evaluated by ChIP-qPCR the levels of core pluripotency TFs and p300 at selected enhancers. Binding of FH-Foxd3 resulted in lower levels of Oct4, Sox2 and p300 at the majority of analyzed enhancers (Figure S6A-C, Figure 5A). The negative effect of Foxd3 on p300 binding was confirmed in Foxd3−/− cells (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Foxd3 shifts the balance of co-activator and co-repressor proteins bound to naïve pluripotency enhancers.

(A-B) ChIP-qPCR analysis for p300 in (A) tetON Foxd3 and WT mESC treated with Dox for three days and (B) Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER mESC treated with TM for three days (Foxd3−/−) or left untreated (Foxd3fl/fl). (C) Strategy used to identify Foxd3 interacting proteins. FT (flow-through); IP (immunoprecipitation). (D) IP with anti-Flag antibody was performed in FH-Foxd3 and WT mESC. Protein levels were detected by Western blotting using antibodies against Foxd3 or Lsd1/Kdm1a. (E) ChIP-seq profiles for Foxd3 and the indicated NuRD subunits around a representative locus (i.e. Tfap2c). (F) Percentage of all or Foxd3−/− Up/EpiLC Down Foxd3 bound regions that are also bound by the indicated NuRD subunits in mESC. * statistically significant (p<0.0001) overlap. (G-H) ChIP-qPCR analysis for Lsd1 in (G) tetON Foxd3 and WT mESC treated with Dox for three days and (H) Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER mESC treated with TM for three days (Foxd3−/−) or left untreated (Foxd3fl/fl). In (A-B) and (G-H) * statistically significant differences in ChIP signals as described in Figure 4. See also Figure S6, Table S3.

Active enhancers in mESC are occupied by both activator and repressor protein complexes (Reynolds et al., 2013). Therefore, we wondered if Foxd3 could alsofacilitate the recruitment of co-repressors, which we tried to identify using mass spectrometry (Figure 5C) (Table S3). Interestingly, a couple of subunits of the NuRD co-repressor complex, Lsd1/Kdm1a and Gatad2a, were among the identified Foxd3 interacting proteins (Brackertz et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2009). The interaction between Foxd3 and Lsd1 was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation followed by western blotting (Figure 5D). The link between Foxd3 and Lsd1 was strengthened by the remarkable fraction of Foxd3 bound regions co-occupied by Lsd1 and, to a lesser extent, by other NuRD components in mESC (Figure 5E-F) (Whyte et al., 2012). However, based on co-immunoprecipitation experiments, no physical interaction was detected between Foxd3 and other NuRD core subunits (i.e. Mbd3 and Hdac1), suggesting that Foxd3 might indirectly interact with NuRD and/or that Foxd3 and Lsd1 interaction might be NuRD independent. Lsd1 is a H3K4me1/2 histone demethylase (Shi et al., 2004), whose function in mESC and early mouse embryogenesis has been previously studied (Foster et al., 2010; Macfarlan et al., 2011; Whyte et al., 2012). Lsd1 is preferentially expressed in the epiblast and its loss results in embryonic lethality soon after implantation (~E6.5) (Foster et al., 2010; Macfarlan et al., 2011). Moreover, upon differentiation, Lsd1−/− mESC display increased cell death and fail to exit pluripotency (Foster et al., 2010; Whyte et al., 2012). Mechanistically, during differentiation Lsd1 facilitates the silencing of pluripotency genes through enhancer decommissioning (Whyte et al., 2012). The functional similarities between Foxd3 and Lsd1 were supported by the transcriptional changes observed in Foxd3−/− mESC and in various Lsd1−/− mESC lines (Foster et al., 2010; Macfarlan et al., 2011) (Figure S6D). Moreover, inspection of the expression changes of mESC in which Lsd1 activity was inhibited upon differentiation (Whyte et al., 2012), revealed that the silencing of Foxd3 target genes was significantly compromised by Lsd1 inhibition (Figure S6E). We hypothesized that Foxd3 could facilitate the recruitment of Lsd1 and other NuRD components to mESC enhancers in order to mediate their decommissioning. Foxd3 overexpression lead to increase Lsd1 and Hdac1 binding at most of the naïve pluripotency enhancers that were analyzed (Figure 5G, Figure S6F), while loss of Foxd3 resulted in lower Lsd1 levels (Figure 5H). These results are in agreement with the changes in H3K4me2 and H3K27ac observed upon either overexpression or loss of Foxd3 (Figure 4B-E) and the enzymatic activities of Lsd1 and NuRD.

Our data suggest that Foxd3 silences mESC enhancers by skewing the balance of regulatory proteins present at these sequences towards repressor complexes. The binding levels of Lsd1, p300, H3K4me2 and H3K27ac were measured in 2i ESC and EpiLC for a subset of naive pluripotency enhancers. Lsd1 binding levels did not increase upon EpiLC differentiation, but rather remained constant or even decreased moderately. However, a significantly more pronounced loss of p300, H3K4me2 and H3K27ac was observed, suggesting a shift in the relative abundance of distinct regulatory activities (i.e. activators vs repressors) present at naïve enhancers during the exit from naïve pluripotency (Figure S6G).

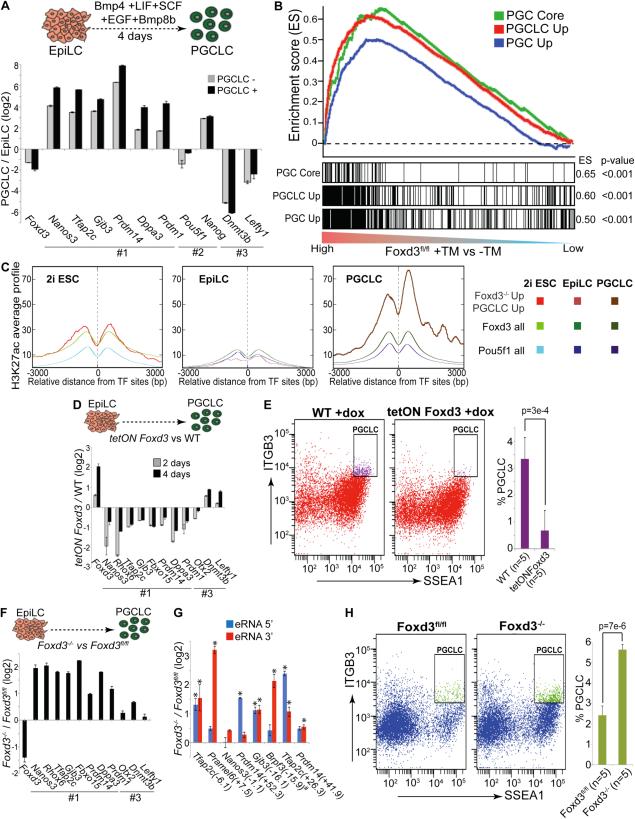

Silencing of Foxd3 is required for PGCLC specification

Foxd3 silenced genes known to be re-activated during establishment of the germline (Hayashi et al., 2011), including Prdm1, Prdm14 and Tfap2c, the three master regulators of PGC specification (Magnúsdóttir et al., 2013; Nakaki et al., 2013) (Figure S1G). Moreover, following implantation, Foxd3 is specifically repressed in the proximo-posterior end of the epiblast, at the exact embryonic location and developmental stage in which PGC induction starts (Sumi et al., 2013). Therefore, we wondered if a de-repression mechanism might be important for PGC specification, whereby Foxd3 needs to be silenced in PGC progenitors to allow the re-activation of naïve pluripotency and early germline genes. To test this, we used an established in vitro protocol in which EpiLC are differentiated into PGCLC (Figure 6A) (Hayashi and Saitou, 2013; Hayashi et al., 2011). During PGCLC differentiation, Foxd3 levels were significantly reduced, while relevant naïve pluripotency/early germline genes and their nearby enhancers became re-activated (Figure 6A, Figure S7A). We also analysed transcriptome data previously generated during the differentiation of EpiLC into PGCLC as well as data comparing the pre-gastrulating E5.75 epiblast and E9.5 PGCs (Hayashi et al., 2011). GSEA analysis revealed that the genes most significantly upregulated during PGC specification were globally repressed by Foxd3 in mESC, (Nakaki et al., 2013)(Figure 6B, Table S1-2, Figure S2D-E). Moreover, a considerable fraction of PGCLC upregulated genes represent direct Foxd3 target genes (~30%, p=2.2e-4), suggesting that the same naïve pluripotency enhancers that are bound by Foxd3 in 2i ESC and that become decommissioned in EpiLC could be re-activated in PGCLC. Analysis of H3K27ac profiles in the course of PGCLC differentiation (Kurimoto et al., 2015) revealed that Foxd3 bound regions located in relative proximity of genes repressed by Foxd3 and activated during PGCLC differentiation (Foxd3−/− Up/PGCLC Up) did not only loose H3K27ac during the transition from 2i ESC to EpiLC but also dramatically re-gained this histone modification in PGCLC (Figure 6C) (Figure S7B).

Figure 6. Silencing of Foxd3 is required for PGCLC specification.

(A) PGCLC were sorted by FACS using antibodies against ITGB3 and SSEA1 (Hayashi et al., 2011). Cells displaying high signals for both ITGB3 and SSEA1 were considered as PGCLC (PGCLC +), while the remaining ones were not (PGCLC −). Transcriptional changes in PGCLC+ and PGCLC− cells relative to EpiLC are presented in log2 scale. (B) GSEA for three different set of genes (PGC core: “core” upregulated genes during PGC specification (Nakaki et al., 2013); PGCLC Up: top 500 upregulated genes during the differentiation of EpiLC into PGCLC (Hayashi et al., 2011); PGC Up: top 500 upregulated genes in E9.5 PGC compared to E5.75 epiblast (Hayashi et al., 2011)) with respect to the global transcriptional changes observed between Foxd3−/− and Foxd3fl/fl mESC. (C) Average H3K27ac ChIP-seq signal profiles in 2i ESC, EpiLC and PGCLC around three different subsets of genomic regions: (i) Foxd3−/− Up/PGCLC Up (Foxd3 bound regions associated with genes upregulated in Foxd3−/− mESC and during PGCLC differentiation); (ii) Foxd3 all; (iii) Pou5f1 all. (D) EpiLC derived from tetON Foxd3 and WT 2i ESC were treated with Dox at the beginning (day 0) and after two days (day 2) of PGCLC differentiation. After four days, the resulting cell aggregates were used to investigate the transcriptional changes between tetON Foxd3 and WT cells. (E) tetON Foxd3 and WT 2iESC were differentiated into PGCLC as described in (D). After four days, PGCLC were quantified by FACS. Representative experiments in WT and tetON Foxd3 cells and the average results from five independent quantifications are presented. P-value was calculated using paired t-test. (F) EpiLC derived from Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER 2i ESC were treated with TM at the beginning (day 0) and after two days (day 2) of PGCLC differentiation (Foxd3−/−) or left untreated (Foxd3fl/fl). After four days, the resulting cell aggregates were used to investigate the transcriptional changes between Foxd3−/− and Foxd3fl/fl cells. (G) Transcriptional changes in eRNA levels between PGCLC aggregates derived as described in (F). * denotes statistically significant differences in eRNA levels as described in Figure 4. (H) Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER 2i ESC were differentiated into PGCLC as described in (F). After four days, the number of PGCLC was quantified by FACS. Representative experiments in Foxd3fl/fl and Foxd3−/− cells and the average results from five independent quantifications are presented. P-value was calculated using paired t-test. See also Figure S7.

To investigate if Foxd3 could compromise the derivation of PGCLC, tetOn Foxd3 and WT 2i ESC were differentiated into EpiLC and subsequently treated with Dox once PGCLC differentiation was started. RT-qPCR experiments showed that tetOn Foxd3 cells displayed significantly reduced expression of relevant pluripotency and germline genes (Figure 6D). In addition, eRNA levels at several Foxd3 bound enhancers re-activated during PGCLC differentiation were also reduced in tetOn Foxd3 cells (Figure S7C). The previous analyses were performed on cell aggregates in which only a fraction of cells represent true PGCLC. To more conclusively assess the importance of silencing Foxd3 during PGCLC specification, we used fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) to quantify the number of PGCLC obtained from tetOn Foxd3 or WT cells (Figure 6E). Chiefly, after four days of PGCLC differentiation, there was an almost four-fold decrease in the number of PGCLC derived from tetOn Foxd3 cells (p=3e-4). The previous experiments were repeated with Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER cells (Figure 6F-H). Overall, the results were the opposite to those obtained with Foxd3 overexpressing cells, as loss of Foxd3 caused increased expression of relevant pluripotency/germline genes, higher eRNA levels at enhancers re-activated during PGCLC differentiation and a more than two-fold increase in the number of PGCLC (Figure 6F-H).

Discussion

Recent advances in mESC culture and differentiation protocols (Hayashi et al., 2011; Kojima et al., 2014; Ying et al., 2008) are revealing that pluripotency entails various cellular states (e.g. naïve, formative, primed), each characterized and maintained by distinct transcriptional networks (Kalkan and Smith, 2014). We now show that Foxd3 plays a major regulatory role during exit from naïve pluripotency and transition to a primed pluripotent state. Previous studies have portrayed Foxd3 as a classical pluripotency regulator that promotes self-renewal and represses differentiation (Liu and Labosky, 2008; Plank et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2014). However, according to both our own and previous data (Figure S1-2), Foxd3 globally represses naïve pluripotency genes, thus supporting a role for this TF in the progression from naïve to primed pluripotency. In light of recent evidences, we argue that the role of many pluripotency regulators might need to be re-evaluated, as each TF can preferentially sustain a distinct pluripotency state (Buecker et al., 2014; Yamaji et al., 2013). Furthermore, our findings are in agreement with the previously reported phenotypes of Foxd3−/− embryos, which die soon after implantation (~E6.5) due to a major loss of epiblast cells (Hanna et al., 2002). This post-implantation developmental arrest could be the result of the abnormally high expression of two major groups of genes repressed by Foxd3: (i) naïve pluripotency and (ii) pro-apoptotic genes. Accumulating evidences suggest that primed pluripotent cells display hypersensitivity to cell death and a low apoptotic threshold (Heyer et al., 2000; Pernaute et al., 2014). Thus, future work should elucidate if repression of pro-apoptotic genes by Foxd3 represents an important requirement for the survival of primed pluripotent cells.

Mechanistically, our data suggests that Foxd3 represses its target genes through enhancer decommissioning, which involves the recruitment of Lsd1 and reduced binding of pluripotency TFs and co-activators (i.e. p300) to active mESC enhancers. According to the model previously proposed to explain the role of Lsd1 during enhancer decommissioning (Whyte et al., 2012), Lsd1 is already present at active enhancers in mESC, but its enzymatic activity is inhibited by the high levels of acetylated histones present at these regulatory regions (Forneris et al., 2005). Once mESC differentiation starts, the abundance and/or binding levels of pluripotency TFs and p300 at active enhancers decreases, resulting in decreased histone acetylation and enabling Lsd1 to demethylate H3K4. This model assumes that Lsd1 remains bound to active enhancers, at least temporally, as they become decommissioned. However, our analysis of Lsd1 binding in 2i ESC and EpiLC shows that Lsd1 binding is either maintained or even decreased as naïve pluripotency enhancers become decommissioned. Nevertheless, this decrease is significantly more pronounced for p300, H3K27ac and H3K4me2. This might be explained by the fact that while Foxd3 favors the recruitment of Lsd1 and interferes with the binding of p300, other pluripotency TFs, such as Nanog and Oct4, are able to recruit both of these antagonistic regulatory proteins (Chen et al., 2008; Liang et al., 2008). Thus, upon differentiation and as the binding of pluripotency TFs to mESC active enhancers decreases, both Lsd1 and p300 binding levels should in principle decrease in a similar fashion. However, persistence of Foxd3 at these enhancers could preferentially retain Lsd1 over p300, with the net effect being a skew in the regulatory proteins present at naïve pluripotency enhancers in favor of repressor complexes, which ultimately leads to enhancer decommissioning (Figure 7) (Reynolds et al., 2013).

Figure 7. Proposed model for Foxd3 regulatory function during mouse peri-implantation development.

Our data suggests that a wave of activation-deactivation of Foxd3 is crucial for the exit from naïve pluripotency and subsequent PGC specification. Foxd3 executes its regulatory function through enhancer decommissioning and consequent repression of relevant target genes.

The previously reported effects of Lsd1/NuRD during enhancer decommissioning involved a major loss in H3K4me1 and H3K27ac (Whyte et al., 2012). Intriguingly, Foxd3-mediated repression lead to a loss in H3K4me2 and H3K27ac but no significant changes in H3K4me1, which coincides with the enhancer chromatin patterns observed during the transition from naïve to primed pluripotency and that do not entail a loss of H3K4me1 (Buecker et al., 2014). Thus, upon exit from naïve pluripotency, the chromatin features of naïve and germline enhancers are not completely erased, as they retain H3K4me1. Rather than being completely inactivated, these enhancers might acquire a transient poised state (Creyghton et al., 2010; Rada-Iglesias et al., 2011) that insulates them from the wave of de novo DNA methylation that occurs during implantation (Guibert et al., 2012; Lesch and Page, 2014; Meissner et al., 2008; Ooi et al., 2007; Seisenberger et al., 2012). In agreement with this hypothesis, regulatory elements associated with naïve pluripotency genes remain hypomethylated in the post-implantation epiblast (Borgel et al., 2010; Osorno et al., 2012). We speculate that the presence of these hypomethylated poised enhancers might be a distinctive feature of the pre-gastrulating post-implantation epiblast that confers germline competence. Following implantation, Foxd3 is repressed in the proximo-posterior epiblast in a Wnt and Prdm1 dependent manner (Magnúsdóttir et al., 2013; Sumi et al., 2013), potentially making these enhancers more accessible to PGC specifiers (e.g. Prdm14) and leading to the reactivation of naïve pluripotency and early germline genes (Figure 7). This is in agreement with the reactivation of these genes preceding the major epigenetic reprogramming events that occur during PGC specification (Guibert et al., 2012; Hackett and Surani, 2014; Saitou and Yamaji, 2012; Saitou et al., 2012). Our model (Figure 7) assumes that the same enhancers control the expression of a subset of naïve pluripotency and early germline genes in both naïve pluripotent and PGCs (Günesdogan et al., 2014). Chiefly, recent H3K27ac maps generated in the course of PGCLC differentiation demonstrate that naïve pluripotency enhancers repressed by Foxd3 in mESC are indeed re-activated in PGCLC (Kurimoto et al., 2015). Furthermore, we have shown, using eRNAs as surrogates of enhancer activity, that Foxd3 can interfere with the re-activation of at least some of these enhancers. Therefore, we propose that, similarly to its importance in other developmental processes (Muhr et al., 2001), de-repression (e.g. through repression of Foxd3) might play a relevant role during PGC specification. Future experiments should elucidate if silencing of Foxd3 in particular and de-repression in general are important for germline specification in vivo.

Experimental Procedures

mESC culture and line derivation

WT LF2 mESC and its derivatives (FH-Foxd3 and tetON Foxd3 mESC lines) were grown, unless otherwise indicated, under feeder-free conditions in Knockout-DMEM medium (KO-DMEM; Life Technologies) containing 15% FBS and LIF. Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER mESC were grown as previously described (Liu and Labosky, 2008) on irradiated mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeder cells and SL medium. mESC were adapted to and maintained in “2i+LIF” conditions using a previously described protocol (Hayashi and Saitou, 2013; Hayashi et al., 2011) with slight modifications. Briefly, mESC were adapted for a minimum of five passages and then grown with “2i+LIF” medium (serum-free N2B27 medium supplemented with MEK inhibitor PD0325901 (0.4 μM, Miltenyi Biotec), GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021 (3 μM, Amsbio) and LIF) in tissue culture dishes pre-treated with gelatin (Sigma).

FH-Foxd3 mESC line was established by transducing LF2 mESCs with FH-Foxd3 pTrip lentivirus followed by selection with neomycin (Ma et al., 2011). tetON Foxd3 mESC line was established by transducing LF2 mESC with FH-Foxd3tetON pTrip lentivirus followed by selection with puromycin. FH-Foxd3tetON pTrip lentiviral vector was generated from a modified pTRIPZ vector backbone in which FH-Foxd3 expression is controlled by a tetracycline response element (TRE). FH-Foxd3 expression was induced by treating tetON Foxd3 mESC with doxycycline (1 μg/μl).

mESC differentiation

2i ESC were differentiated into EpiLC as previously described (Hayashi et al., 2011). 3×105 cells were plated on 6-well culture plates coated with 16.7 μg/ml fibronectin (Merck-Millipore) and grown in N2B27 medium supplemented with KSR (1%, Life Technologies), bFGF (12 ng/ml, Life Technologies) and Activin A (20 ng/ml , Peprotech) for two days. 2i ESC were also differentiated by withdrawing 2i inhibitors and LIF from the N2B27 medium (Betschinger et al., 2013). For commitment assays (Leeb et al., 2014), 2i ESC were differentiated into EpiLC for three days, re-plated and grown in “2i+LIF” medium for at least 48 hours and then maintained under “2i+LIF” conditions for at least two passages. For rescue experiments, Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER mESC were transfected with a Foxd3 or a GFP expressing vector (pcDNA3.1-Foxd3), treated with TM for two days and then differentiated into EpiLC.

PGCLC induction

PGCLC were derived using a previously described protocol (Hayashi and Saitou, 2013; Hayashi et al., 2011). 2×103 day 2 EpiLC were plated in a single well from a 96-well Lipidure-Coat Plate (Amsbio) and grown in serum-free GK15 medium (GMEM (Life Technologies), KSR (15%, Life Technologies), nonessential amino acids (Life Technologies), sodium pyruvate (1 mM, Life Technologies), 2-mercaptoethanol (0.1 mM, Life Technologies), L-glutamine (2 mM, Life Technologies), BMP4 (500 ng/ml; Miltenyi Biotec), SCF (100 ng/ml; Miltenyi Biotec), BMP8b (500 ng/ml; R&D Systems), EGF (50 ng/ml; Miltenyi Biotec) and LIF for four days.

ChIP-seq

DNA libraries from HA ChIP, Flag ChIP and corresponding input DNA samples obtained in FH-Foxd3 mESC were prepared according to Illumina protocol and sequenced using Illumina Genome Analyzer. Mapped sequences were analysed by QuEST 2.4 (Valouev et al., 2008) using the following settings: KDE bandwith=30, ChIP seeding fold enrichment=30, ChIP extension fold enrichment=3, ChIP-to-background fold enrichment=3.

RNA-seq

RNA-seq libraries were sequenced with a 2 × 100–bp strand-specific protocol on a HiSeq 2500 sequencer (Illumina). Data were analyzed using a high-throughput next-generation sequencing analysis pipeline as described in supplementary material (Wagle et al., 2015).

PGCLC sorting and quantification by FACS

Sorting and quantification of PGCLC was performed according to a previously described protocol (Hayashi and Saitou, 2013). After four days of induction, PGCLC were stained with antibodies against ITGB3 (104307, Biolegend) and SSEA1 (50-8813-41, eBioscience) conjugated with PE and Alexa Fluor 647, respectively. PGCLC quantification was performed with a FACSCantoII Cytometer (BD Bioscience) equipped with BD FACSDiva Software. PGCLC sorting was performed on a FACSAriaIII cell sorter (BD Bioscience).

RNA-seq and ChIP-seq datasets generated in this study have been deposited into GEO repository under accession number GSE70547. All primers used in this study are presented in Table S4.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank M.A. Nieto, Argyris Papantonis and Miguel Manzanares for insightful comments and critical reading of the manuscript; Karen Reuter and Gunter Rappl for technical assistance with FACS experiments; Patricia Labosky for generously providing the Foxd3fl/fl;Cre-ER mESC line. Work in the Rada-Iglesias laboratory is supported by CMMC intramural funding, DFG Research Grant (RA 2547/1-1), UoC Advanced Researcher Group Grant, CECAD grant and Fritz Thyssen Stiftung grant.

References

- Andersson R, Gebhard C, Miguel-Escalada I, Hoof I, Bornholdt J, Boyd M, Chen Y, Zhao X, Schmidl C, Suzuki T, et al. An atlas of active enhancers across human cell types and tissues. Nature. 2014;507:455–461. doi: 10.1038/nature12787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betschinger J, Nichols J, Dietmann S, Corrin PD, Paddison PJ, Smith A. Exit from pluripotency is gated by intracellular redistribution of the bHLH transcription factor Tfe3. Cell. 2013;153:335–347. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn S, Zinzen RP, Girardot C, Gustafson EH, Perez-Gonzalez A, Delhomme N, Ghavi-Helm Y, Wilczynski B, Riddell A, Furlong EEM. Tissue-specific analysis of chromatin state identifies temporal signatures of enhancer activity during embryonic development. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:148–156. doi: 10.1038/ng.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgel J, Guibert S, Li Y, Chiba H, Schubeler D, Sasaki H, Forne T, Weber M. Targets and dynamics of promoter DNA methylation during early mouse development. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:1093–1100. doi: 10.1038/ng.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackertz M, Boeke J, Zhang R, Renkawitz R. Two highly related p66 proteins comprise a new family of potent transcriptional repressors interacting with MBD2 and MBD3. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:40958–40966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buecker C, Srinivasan R, Wu Z, Calo E, Acampora D, Faial T, Simeone A, Tan M, Swigut T, Wysocka J. Reorganization of enhancer patterns in transition from naive to primed pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:838–853. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Xu H, Yuan P, Fang F, Huss M, Vega VB, Wong E, Orlov YL, Zhang W, Jiang J, et al. Integration of external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:1106–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creyghton MP, Cheng AW, Welstead GG, Kooistra T, Carey BW, Steine EJ, Hanna J, Lodato MA, Frampton GM, Sharp PA, et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:21931–21936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016071107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JR, Selvaraj S, Yue F, Kim A, Li Y, Shen Y, Hu M, Liu JS, Ren B. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature. 2012;485:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature11082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn S-J, Martello G, Yordanov B, Emmott S, Smith AG. Defining an essential transcription factor program for naive pluripotency. Science. 2014;344:1156–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1248882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari KJ, Scelfo A, Jammula S, Cuomo A, Barozzi I, Stutzer A, Fischle W, Bonaldi T, Pasini D. Polycomb-dependent H3K27me1 and H3K27me2 regulate active transcription and enhancer fidelity. Mol. Cell. 2014;53:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forneris F, Binda C, Vanoni MA, Battaglioli E, Mattevi A. Human histone demethylase LSD1 reads the histone code. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:41360–41365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509549200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster CT, Dovey OM, Lezina L, Luo JL, Gant TW, Barlev N, Bradley A, Cowley SM. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 regulates the embryonic transcriptome and CoREST stability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010;30:4851–4863. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00521-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guibert S, Forné T, Weber M. Global profiling of DNA methylation erasure in mouse primordial germ cells. Genome Res. 2012;22:633–641. doi: 10.1101/gr.130997.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günesdogan U, Magnúsdóttir E, Surani MA. Primoridal germ cell specification: a context-dependent cellular differentiation event. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2014;369 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett JA, Surani MA. Regulatory principles of pluripotency: from the ground state up. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:416–430. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna LA, Foreman RK, Tarasenko IA, Kessler DS, Labosky PA. Requirement for Foxd3 in maintaining pluripotent cells of the early mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2650–2661. doi: 10.1101/gad.1020502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Saitou M. Generation of eggs from mouse embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:1513–1524. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Ohta H, Kurimoto K, Aramaki S, Saitou M. Reconstitution of the mouse germ cell specification pathway in culture by pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2011;146:519–532. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyer BS, MacAuley A, Behrendtsen O, Werb Z. Hypersensitivity to DNA damage leads to increased apoptosis during early mouse development. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2072–2084. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkan T, Smith A. Mapping the route from naive pluripotency to lineage specification. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2014;369 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima Y, Kaufman-Francis K, Studdert JB, Steiner KA, Power MD, Loebel DAF, Jones V, Hor A, de Alencastro G, Logan GJ, et al. The transcriptional and functional properties of mouse epiblast stem cells resemble the anterior primitive streak. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurimoto K, Yabuta Y, Hayashi K, Ohta H, Kiyonari H, Mitani T, Moritoki Y, Kohri K, Kimura H, Yamamoto T, et al. Quantitative Dynamics of Chromatin Remodeling during Germ Cell Specification from Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:517–532. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeb M, Dietmann S, Paramor M, Niwa H, Smith A. Genetic exploration of the exit from self-renewal using haploid embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch HG, Smith A. The mammalian germline as a pluripotency cycle. Dev. Camb. Engl. 2013;140:2495–2501. doi: 10.1242/dev.091603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesch BJ, Page DC. Poised chromatin in the mammalian germ line. Dev. Camb. Engl. 2014;141:3619–3626. doi: 10.1242/dev.113027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Wan M, Zhang Y, Gu P, Xin H, Jung SY, Qin J, Wong J, Cooney AJ, Liu D, et al. Nanog and Oct4 associate with unique transcriptional repression complexes in embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:731–739. doi: 10.1038/ncb1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Labosky PA. Regulation of embryonic stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency by Foxd3. Stem Cells Dayt. Ohio. 2008;26:2475–2484. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, Swigut T, Valouev A, Rada-Iglesias A, Wysocka J. Sequence-specific regulator Prdm14 safeguards mouse ESCs from entering extraembryonic endoderm fates. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:120–127. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlan TS, Gifford WD, Agarwal S, Driscoll S, Lettieri K, Wang J, Andrews SE, Franco L, Rosenfeld MG, Ren B, et al. Endogenous retroviruses and neighboring genes are coordinately repressed by LSD1/KDM1A. Genes Dev. 2011;25:594–607. doi: 10.1101/gad.2008511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnúsdóttir E, Dietmann S, Murakami K, Gunesdogan U, Tang F, Bao S, Diamanti E, Lao K, Gottgens B, Azim Surani M. A tripartite transcription factor network regulates primordial germ cell specification in mice. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013;15:905–915. doi: 10.1038/ncb2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marson A, Levine SS, Cole MF, Frampton GM, Brambrink T, Johnstone S, Guenther MG, Johnston WK, Wernig M, Newman J, et al. Connecting microRNA genes to the core transcriptional regulatory circuitry of embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;134:521–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CY, Bristor D, Hiller M, Clarke SL, Schaar BT, Lowe CB, Wenger AM, Bejerano G. GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner A, Mikkelsen TS, Gu H, Wernig M, Hanna J, Sivachenko A, Zhang X, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Jaffe DB, et al. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature. 2008;454:766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature07107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhr J, Andersson E, Persson M, Jessell TM, Ericson J. Groucho-mediated transcriptional repression establishes progenitor cell pattern and neuronal fate in the ventral neural tube. Cell. 2001;104:861–873. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaki F, Hayashi K, Ohta H, Kurimoto K, Yabuta Y, Saitou M. Induction of mouse germ-cell fate by transcription factors in vitro. Nature. 2013;501:222–226. doi: 10.1038/nature12417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohinata Y, Ohta H, Shigeta M, Yamanaka K, Wakayama T, Saitou M. A signaling principle for the specification of the germ cell lineage in mice. Cell. 2009;137:571–584. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi SKT, Qiu C, Bernstein E, Li K, Jia D, Yang Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Lin S-P, Allis CD, et al. DNMT3L connects unmethylated lysine 4 of histone H3 to de novo methylation of DNA. Nature. 2007;448:714–717. doi: 10.1038/nature05987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorno R, Tsakiridis A, Wong F, Cambray N, Economou C, Wilkie R, Blin G, Scotting PJ, Chambers I, Wilson V. The developmental dismantling of pluripotency is reversed by ectopic Oct4 expression. Dev. Camb. Engl. 2012;139:2288–2298. doi: 10.1242/dev.078071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekowska A, Benoukraf T, Zacarias-Cabeza J, Belhocine M, Koch F, Holota H, Imbert J, Andrau J-C, Ferrier P, Spicuglia S. H3K4 tri-methylation provides an epigenetic signature of active enhancers. EMBO J. 2011;30:4198–4210. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernaute B, Spruce T, Smith KM, Sanchez-Nieto JM, Manzanares M, Cobb B, Rodriguez TA. MicroRNAs control the apoptotic threshold in primed pluripotent stem cells through regulation of BIM. Genes Dev. 2014;28:1873–1878. doi: 10.1101/gad.245621.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plank JL, Suflita MT, Galindo CL, Labosky PA. Transcriptional targets of Foxd3 in murine ES cells. Stem Cell Res. 2014;12:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rada-Iglesias A, Bajpai R, Swigut T, Brugmann SA, Flynn RA, Wysocka J. A unique chromatin signature uncovers early developmental enhancers in humans. Nature. 2011;470:279–283. doi: 10.1038/nature09692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds N, O'Shaughnessy A, Hendrich B. Transcriptional repressors: multifaceted regulators of gene expression. Dev. Camb. Engl. 2013;140:505–512. doi: 10.1242/dev.083105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou M, Yamaji M. Primordial germ cells in mice. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012;4 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou M, Kagiwada S, Kurimoto K. Epigenetic reprogramming in mouse pre-implantation development and primordial germ cells. Dev. Camb. Engl. 2012;139:15–31. doi: 10.1242/dev.050849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seisenberger S, Andrews S, Krueger F, Arand J, Walter J, Santos F, Popp C, Thienpont B, Dean W, Reik W. The dynamics of genome-wide DNA methylation reprogramming in mouse primordial germ cells. Mol. Cell. 2012;48:849–862. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, Casero RA, Shi Y. Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell. 2004;119:941–953. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi T, Oki S, Kitajima K, Meno C. Epiblast ground state is controlled by canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the postimplantation mouse embryo and epiblast stem cells. PloS One. 2013;8:e63378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valouev A, Johnson DS, Sundquist A, Medina C, Anton E, Batzoglou S, Myers RM, Sidow A. Genome-wide analysis of transcription factor binding sites based on ChIP-Seq data. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagle P, Nikolić M, Frommolt P. QuickNGS elevates Next-Generation Sequencing data analysis to a new level of automation. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:487. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1695-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamstad JA, Alexander JM, Truty RM, Shrikumar A, Li F, Eilertson KE, Ding H, Wylie JN, Pico AR, Capra JA, et al. Dynamic and coordinated epigenetic regulation of developmental transitions in the cardiac lineage. Cell. 2012;151:206–220. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang H, Chen Y, Sun Y, Yang F, Yu W, Liang J, Sun L, Yang X, Shi L, et al. LSD1 is a subunit of the NuRD complex and targets the metastasis programs in breast cancer. Cell. 2009;138:660–672. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte WA, Bilodeau S, Orlando DA, Hoke HA, Frampton GM, Foster CT, Cowley SM, Young RA. Enhancer decommissioning by LSD1 during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature. 2012;482:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature10805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte WA, Orlando DA, Hnisz D, Abraham BJ, Lin CY, Kagey MH, Rahl PB, Lee TI, Young RA. Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell. 2013;153:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaklichkin S, Steiner AB, Lu Q, Kessler DS. FoxD3 and Grg4 physically interact to repress transcription and induce mesoderm in Xenopus. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:2548–2557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607412200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji M, Seki Y, Kurimoto K, Yabuta Y, Yuasa M, Shigeta M, Yamanaka K, Ohinata Y, Saitou M. Critical function of Prdm14 for the establishment of the germ cell lineage in mice. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1016–1022. doi: 10.1038/ng.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji M, Ueda J, Hayashi K, Ohta H, Yabuta Y, Kurimoto K, Nakato R, Yamada Y, Shirahige K, Saitou M. PRDM14 ensures naive pluripotency through dual regulation of signaling and epigenetic pathways in mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:368–382. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Q-L, Wray J, Nichols J, Batlle-Morera L, Doble B, Woodgett J, Cohen P, Smith A. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature. 2008;453:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature06968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Zhang S, Jin Y. Foxd3 suppresses NFAT-mediated differentiation to maintain self-renewal of embryonic stem cells. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:1286–1296. doi: 10.15252/embr.201438643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.