Abstract

We conducted a literature review on the effect of breastfeeding and dummy (pacifier) use on sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). From 4343 abstracts, we identified 35 relevant studies on breastfeeding and SIDS, 27 on dummy use and SIDS and 59 on dummy use versus breastfeeding.

Conclusion

We found ample evidence that both breastfeeding and dummy use reduce the risk of SIDS. There has been a general reluctance to endorse dummy use in case it has a detrimental effect of breastfeeding. However, recent evidence suggests that dummy use might not be as harmful to breastfeeding as previously believed.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, Dummy, Pacifier, Review, Sudden infant death syndrome

Key notes.

We conducted a literature review on the effect of breastfeeding and dummy (pacifier) use on sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), focusing on more than 100 full texts.

Our review found ample evidence that both breastfeeding and dummy use reduced the risk of SIDS.

There has been general reluctance to endorse dummy use in case it has a detrimental effect on breastfeeding, but recent evidence suggests it might not be as harmful to breastfeeding as previously believed

Introduction

Most countries experienced an increased prevalence in sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) during the 1980s, followed by a dramatic decrease after supine sleeping was recommended as the normal sleeping position for infants around 1990 1. In Sweden, SIDS decreased from 1.2 deaths per 1000 live births in 1990 to 0.2 in 2012. The original Swedish advice to parents to reduce the risk of SIDS was updated in 2003, and then, in 2006, new findings regarding dummy (pacifier) use and bed sharing were discussed. In 2014, there was a further need to discuss these factors in greater depth and to revise the advice in accordance with new findings. Moreover, there was a need to convey new information on the prevention of skull asymmetries, which had emerged as a more frequent problem as a result of the campaign to reduce the risk of SIDS and a higher prevalence of supine sleeping.

Since the 1930s 2, there have been discussions about whether bottle‐feeding was a risk factor for cot death. Even though studies conducted using meta‐techniques 3 pointed towards a protective effect, it was still unclear whether this was due to the physiological effect of breastmilk or whether it was a proxy for socio‐economic factors 4.

The risk‐reducing effect that dummy use had on SIDS was shown by Mitchell et al. in 1993 in the New Zealand Cot Death Study 5. Following this, all studies investigating this association have found similar results.

The aim of the present study was to perform a literature review on breastfeeding and dummy use and how they influenced one another and to renew the advice to the Swedish public and to personnel working in hospitals and health services.

Methods

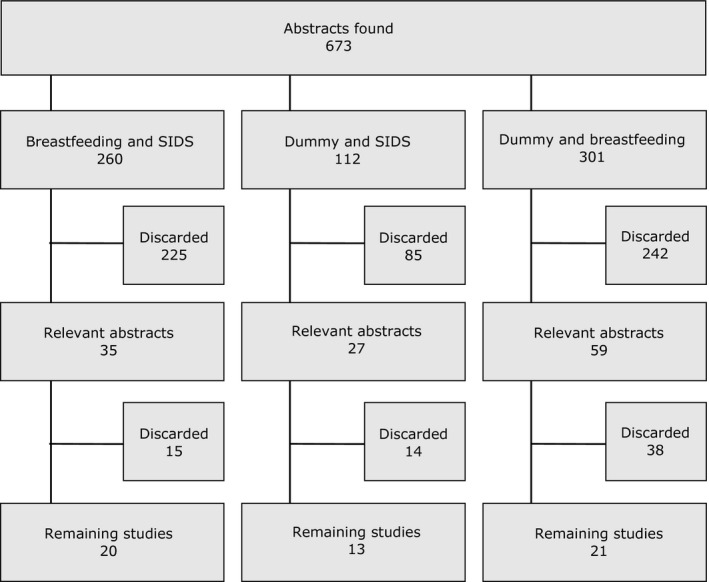

Literature searches were carried out between spring 2012 and spring 2013, and this identified 4343 abstracts. We reviewed 260 abstracts on breastfeeding and SIDS, and 35 were considered relevant to the research question. When it came to dummy use and SIDS, we reviewed 112, and 27 were considered relevant. As there was a strong negative correlation between breastfeeding and dummy use, we also wanted to study this. We reviewed 301 abstracts, and 59 were relevant. After having read the full papers, we included studies showing effect measures. There were 20 concerning breastfeeding and SIDS, 13 concerning dummy use and SIDS and 21 concerning dummy and breastfeeding (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the number of abstracts and articles reviewed.

Results

Breastfeeding and SIDS

We examined 17 observational studies (Table 1) and found that breastfeeding was reported to have provided a protective effect on SIDS in ten studies 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. No protective effects were found in the other seven 4, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21.

Table 1.

Studies on the association between breastfeeding and sudden infant death 1990–2012. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals

| Study | Effect (OR (95% CI) | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Observational studies | ||

| Mitchell, N Z Med J 1991 6 | aOR 2.93 (1.84, 4.67) (bottle) |

162 cases and 589 controls New Zealand |

| Mitchell, BMJ 1993 7 |

aOR (bottle) maori: 2.60 (1.73, 3.91) other: 2.04 (1.46, 2.84) |

485 cases and 1800 controls New Zealand |

| Ford, Int J Epidemiol 1993 8 |

Exclusive breastfeeding aOR = 0.65 (0.46, 0.91) |

485 cases and 1800 controls New Zealand |

| Ponsonby, Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1995 16 |

Mixed aOR 1.2 (0.5, 2.7) Bottle aOR 1.8 (0.7, 4.8) |

98 cases and 190 controls Tasmania |

| Gilbert, BMJ 1995 17 |

Mixed 1.8 (0.7, 4.8) Bottle 1.2 (0.5, 2.7) |

98 cases and 196 controls Avon, N Somerset, England |

| Klonoff‐Cohen, JAMA 1995 9 |

Overall: aOR 0.41 (0.22, 0.79) Nonsmokers: aOR 0.37 (0.19, 0.72) Smokers: aOR 1.38 (0.16, 12.03) |

200 cases between 1989 and 1992 and 200 controls Five counties in Southern California |

| Fleming, BMJ 1996 18 | aOR 1.06 (0.57, 1.98) |

195 cases and 780 controls Southwest, Yorkshire and Trent, England |

| Schellscheidt, Eur J Pediatr 1997 10 | Bottle: aOR 7.7 (2.7, 22.3) |

75 cases and 156 controls Münster, Germany |

| Mitchell, Pediatrics 1997 19 |

Breastfeeding 1.32 (0.72, 2.41) Exclusive breastfeeding 1.54 (0.95, 2.46) |

127 cases and 922 controls New Zealand |

| l'Hoir, Arch Dis Child 1998 11 | aOR 0.09 (0.01, 0.88) |

73 cases and 146 controls The Netherlands |

| Tanaka, Environ Health Prev Med 2001 12 |

Bottle: aOR 4.92 (2.78, 9.63). |

386 cases and 386 controls Japan Autopsy rate 36% |

| Törö, Scand J Prim Health Care 2001 20 | Crude OR1.8 (0.6, 5.9) |

18 cases and 74 controls Budapest, Hungary Small study |

| Alm, Arch Dis Child 2002 13 |

Exclusive breastfeeding >4 months aOR 0.2 (0.1, 0.4) Any breastfeeding aOR 0.2 (0.1, 0.5) |

244 cases and 869 controls Denmark, Norway and Sweden |

| Fleming, Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2003 4 | aOR 1.15 (0.77, 1.72) |

323 cases and 323 controls with a similar socio‐economic profile 363 cases and 1452 controls The Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy, UK |

| Hauck, Pediatrics 2003 14 |

Breastfeeding (ever) aOR 0.4 (0.2, 0.7) Breastfeeding (current) aOR 0.3 (0.2, 0.7) |

260 cases and 260 controls Chicago |

| Chen, Pediatrics 2004 21 | Crude OR 0.84 (0.67, 1.05) |

1204 cases and 7740 controls 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey (NMIHS) data |

| Venneman, Paediatrics 2009 15 |

Exclusive breastfeeding aOR: 0.27 (0.13, 0.56) Mixed feeding aOR: 0.29 (0.16, 0.53) |

333 cases and 998 controls Germany |

| Meta‐analyses | ||

| McVea, J Hum Lact 2000 22 | OR 2.11 (1.66, 2.68) | 19 studies, 1966–1997 |

| Ip, Breastfeed Med 2009 23 |

Any breastfeeding: aOR 0.64 (0.51, 0.81) |

Six studies, published after McVea 2000 |

| Hauck, Pediatrics 2011 3 |

Summary OR: sOR 0.55 (0.44, 0.69) |

18 studies, 1966–2009 |

All three of the meta‐analyses that our search identified 3, 22, 23 showed that breastfeeding had a protective effect on SIDS.

Dummies and SIDS

We found 11 observational studies 5, 14, 18, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 that consistently showed a risk reduction of about 50% if the infant used a dummy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Studies on the association between the use of dummy and sudden infant death 1990–2012. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals

| Study | Effect [OR (95% CI)] | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Observational studies | ||

| Mitchell, Arch Dis Child 1993 5 |

Any use aOR 0.71 (0.50, 1.01) Last sleep aOR 0.43 (0.24, 0.78) |

485 cases and 1800 controls New Zealand |

| Fleming, BMJ 1996 18 | aOR 0.38 (0.21, 0.70) |

195 cases and 780 controls CESDI, UK |

| Arnestad, Eur J Pediatr 1997 24 |

Night: OR 0.27 (0.14, 0.51) Day: OR 0.36 (0.19, 0.69) |

167 cases and 352 controls Norway |

| Fleming, Arch Dis Child 1999 25 | aOR 0.41 (0.22, 0.77) |

325 cases and 1300 controls CESDI, UK |

| L'Hoir, Eur J Pediatr 1999 26 |

Usually aOR 0.24 (0.11, 0.51) Last sleep aOR 0.16 (0.07, 0.36) |

73 cases and 146 controls The Netherlands |

| McGarvey, Arch Dis Child 2003 27 | aOR 5.83 (2.37, 14.36) |

203 cases and 622 controls Ireland |

| Hauck, Pediatrics 2003 14 | aOR 0.3 (0.2, 0.5) |

260 cases and 260 controls Chicago, USA |

| Vennemann, Acta Paediatr 2005 28 | aOR 0.39 (0.25, 0.59) |

333 cases and 998 controls GeSID, Germany |

| Li, BMJ 2006 29 | aOR 0.08 (0.03, 0.21) |

185 cases and 312 controls 11 counties in California |

| Thompson, J Pediatr 2006 30 |

Face down: aOR 1.18 (0.57, 2.47) Face up: aOR 0.18 (0.07, 0.48) |

485 cases and 1800 controls New Zealand Cot Death Study |

| Moon, Matern Child Health J 2012 31 | aOR 0.30 (0.17, 0.52) |

260 cases and 260 controls Chicago, USA |

| Meta‐analyses | ||

| Hauck, Pediatrics 2005 32 |

Usually aOR 0.71 (0.59, 0.85) Last sleep aOR 0.39 (0.31, 0.50), |

7 studies, 1966–2004 |

| Mitchell, Pediatrics 2006 33 |

Routine use Pooled OR 0.83 (0.75, 0.93) Last sleep Pooled OR 0.48 (0.43, 0.54) |

Routine use, 7 case–control studies Last sleep, 8 case–control studies |

There were also two meta‐analyses 32, 33 that gave approximately the same odds ratio of about 0.5.

Dummies and breastfeeding

A negative correlation between the use of a dummy and successful breastfeeding was found in all 14 studies 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 published between 1999 and 2012 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Studies of the association between using a dummy and breastfeeding 1999–2012. Odds ratios, relative risks and hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals

| Study | Effect (OR (95% CI) | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Observational studies | ||

| Vogel, Acta Paediatr 1999 34 | Risk for shorter duration of breastfeeding of daily dummy use: a OR 1.62 (1.20, 2.18) |

350 mother–infant pairs New Zealand |

| Riva, Acta Paediatr 1999 35 |

Pacifier use was significantly associated with stopping breastfeeding: Partial breastfeeding aOR 1.18 (1.04, 1.34) Exclusive breastfeeding aOR 1.35 (1.18, 1.55) |

1601 mothers Italy |

| Aarts, Pediatrics 1999 36 |

Hazard ratio for shortening of breastfeeding duration Dummy use: Often aOR 1.62 (1.28, 2.07) Frequent aOR 2.17 (1.53, 3.09) |

506 mother–infant pairs, Sweden |

| Howard, Pediatrics 1999 37 |

The introduction of a dummy at six weeks was associated with a significantly increased risk of shortened breastfeeding. Hazard ratio, 1.53 (1.15, 2.05), (exclusive) hazard ratio 1.61 (1.19, 2.19) (any) |

265 breastfeeding mothers. Greater Rochester, NY, US |

| Vogel, J Paediatr Child Health 2001 38 |

Early cessation, aRR 1.71 (1.29, 2.28) Reduced duration of exclusive breastfeeding, aRR 1.35 (1.05, 1.74) |

350 mothers with infants born from May to December 1996 at North Shore Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand |

| Marques, Pediatrics 2001 39 |

A dummy in the first week increased the risk of formula within one month. aOR 4.01 (2.07, 7.78) |

364 mothers from four small cities in Pernambuco, north‐eastern Brazil |

| Ingram, Midwifery 2002 40 |

Not using a dummy was significantly associated with breastfeeding at two weeks aOR 2.6 (1.6, 4.0) |

1400 mothers from South Bristol, England, who were breastfeeding at discharge. |

| Binns and Scott, Breastfeed Rev 2002 41 |

A dummy at two weeks was inversely associated with breastfeeding at six months aOR 0.40 (0.25, 0.63) |

556 mothers Perth, Australia |

| Giovannini, Acta Paediatr 2004 42 | A dummy in the first month of life increased the risk of cessation of exclusive breastfeeding. aOR 1.28 (1.13, 1.45) | 2450 infants randomly chosen from all infants born in November 1999 in Italy. |

| Nelson, J Hum Lact 2005 43 |

A dummy (sometimes or often) increased the risk of bottle‐feeding. aOR 2.35 (1.61, 3.42) (‘sometimes’) aOR 4.56 (2.33, 8.91) (‘often’) |

2844 infants The International Child Care Practices Study (ICCPS); 21 centres in 17 countries (America, Europe, Asia and Oceania) |

| Scott, Pediatrics 2006 44 | The introduction of a dummy before the age of four weeks increased the risk of non‐exclusive breastfeeding at six months. aOR 1.92 (1.39, 2.64) |

587 women Perth, Australia |

| Santo, Birth 2007 45 |

A dummy in the first month increased the risk of cessation of exclusive breastfeeding before six months. Hazard rate 1.53 (1.12, 2.11) |

220 healthy mother–infant pairs Porto Alegre, Brazil |

| Kronborg, Birth 2009 46 |

A dummy in the first two weeks increased the risk of breastfeeding cessation before six months. aOR 1.42 (1.18, 1.72) |

570 mother–infant pairs in western Denmark |

| Feldens, Matern Child Health J 2012 47 |

A dummy in the first month increased the risk of breastfeeding cessation before one year of age. aRR 3.12 (2.13, 4.57) |

360 participants Sao Leopoldo in southern Brazil |

| Meta‐analyses on observational studies | ||

| Karabulut, Turk J Pediatr 2009 48 |

Dummy use reduced the duration of any breastfeeding: cOR 2.760 (2.083, 3.657) aOR 1.952 1.662, 2.293) |

Twelve trials with weaning from exclusive breastfeeding and 19 trials with cessation of any breastfeeding. 1993–2005 |

| Randomised controlled studies (RCTs) | ||

| Schubiger, Eur J Pediatr 1997 49 |

No significant differences between groups. ‘UNICEF’ vs. ‘standard’: day 5: 100% vs. 99%; two months: 88% vs. 88%; four months: 75% vs. 71%; six months: 57% vs. 55% |

UNICEF group: 294 ‘Standard’ group: 308 The ‘standard’ group was offered a dummy and formula. Ten maternity services at Swiss hospitals |

| Kramer, JAMA 2001 50 |

At three months, 18.9% of the intervention group were weaned and, in the control group, 18.3%. RR 1.0 (0.6, 1.7) |

258 infants The intervention consisted of a recommendation to abstain from a dummy and suggestions of other comforting measures. Montreal, Quebec |

| Howard, Pediatrics 2003 51 | Early, as compared with late, dummy use shortened overall duration (adjusted hazard ratio: 1.22 (1.03, 1.44) but did not affect exclusive or full duration |

700 infants Rochester General Hospital, Ohio, USA |

| Collins, BMJ 2004 52 |

Any breastfeeding three months after discharge 0.99 (0.56, 1.77) Any breastfeeding six months after discharge 1.23 (0.66, 2.30) |

319 preterm (23–33 week) infants Two hospitals in Australia between April 1996 and November 1999 |

| Jenik, J Pediatr 2009 53 | Risk difference 0.4% (−4.9%, 4.1%) |

1021 mothers highly motivated to breastfeed. Five hospitals in Argentina |

| Meta‐analyses on RCTs | ||

| Jaafar, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011 54 |

Dummy use in healthy breastfeeding infants had no significant effect on the proportion of infants exclusively breastfed at three months RR 1.00 (0.95, 1.06) |

Two RCTs, 1302 infants (included Jenik 2009 and Kramer 2001; excluded Schubiger 1997, Collins 2004 and Howard 2003) |

A meta‐analysis that covered many of these studies 48 did not alter the finding of a strong negative association. However, five randomised controlled studies (RCTs) have been performed 49, 50, 51, 52, 53 to date. Four of them 49, 50, 52, 53 did not find that a dummy reduced the duration of breastfeeding, while one 51 found an increased risk of earlier weaning.

In 2011, Jaafar 54 conducted a meta‐analysis on the RCTs carried out by Jenik 53 and Kramer 50, which concluded that using a dummy did not affect the chance of exclusive breastfeeding at three months.

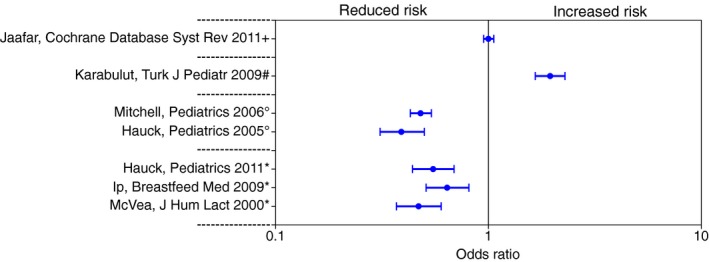

Pooled odds ratios

Figure 2 shows the pooled odds ratios of the seven meta‐analyses: three on breastfeeding and SIDS, two on dummies and SIDS, one meta‐analysis based on observational studies on dummies and breastfeeding and one meta‐analysis based on two RCTs on dummies and breastfeeding.

Figure 2.

Pooled odds ratios from meta‐analyses of: (+) two randomised controlled studies on the effect of a dummy on breastfeeding duration, (#) observational studies on the effect of a dummy on shortened breastfeeding, (°) observational studies on the effect of dummy use on sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and (*) observational studies on the effect of breastfeeding on SIDS.

Discussion

Breastfeeding and SIDS

The mechanism behind the beneficial effect of breastfeeding is still unclear. The most common explanation is that the risk of SIDS is increased by viral infections 55 and that breastfeeding has a protective effect on these infections 56. There are also studies that show that breastfed infants are more easily aroused than bottle‐fed ones. It has been suggested that this might be due to alterations in the neurochemical composition of the brain, for example, that the brains of breastfed infants contain different amounts of docosahexaenoic acid, which is a long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acid (LCPUFA) present in fish oil and breastmilk. However, since the beginning of this millennium, LCPUFAs have been added to infant formulas.

To summarise, there is a great deal of evidence pointing towards a risk‐reducing effect, but it is not undisputed. If models could be more efficiently adjusted for social disadvantage, it is possible that the results of more studies might deviate towards nonsignificance. However, breastfeeding during the first months of life is desirable for many reasons and whether or not it has a protective effect on SIDS should not affect the recommendation to breastfeed for as long as possible and whenever feasible.

Dummies and SIDS

The way in which a dummy can reduce the risk of SIDS is still unclear. It has been suggested that it could interfere with the auditory arousal threshold and modify the autonomous control of the heart. However, in another study, it has been shown that there is no difference in the number of awakenings between infants using or not using dummies.

It has also been suggested that the mechanism could be purely mechanical, as sucking a dummy induces a forward movement of the mandible 57.

A position paper from the Physiology and Epidemiology Working Groups of the International Society for the Study and Prevention of Perinatal and Infant Death suggested that it is not the dummy per se that confers the protection, but that it is a proxy for something else. A very plausible suggestion is that the more arousable babies are given a dummy more frequently and that these may be innately protected, as they are more easily aroused from sleep 58.

Dummies and breastfeeding

The fact that 20 of the 21 studies found a correlation between dummy use and unsuccessful breastfeeding is a strong indication that this is a real association. The interpretation of this has been that the dummy interferes with breastfeeding initiation and continuation, which has led to the practice of advising against the use of dummies in breastfeeding promotion. The ninth of the ten ‘steps to successful breastfeeding’ from the World Health Organization says ‘Give no artificial teats or pacifiers (also called dummies or soothers) to breastfeeding infants’.

However, many of these studies raise the question themselves of whether this association is real or an example of reverse causation, in that failing to breastfeed is the primary event that triggers the need to relieve the need for sucking by soothing the baby with a dummy. However, the design of the studies makes it impossible to determine the direction of the causality.

As so many of the reviewed studies showed this strong negative association, it is not surprising that a meta‐analysis 48 comes to the same conclusion. However, several RCTs (despite several drawbacks, even in the well‐designed ones) and a meta‐analysis of the two least problematic RCTs, found no increased risk of unsuccessful breastfeeding following the introduction of dummies. These findings strengthen the case to not advise against a dummy after breastfeeding has been established, which usually occurs within two weeks in term infants.

Of course this recommendation has been discussed and one argument that has been advanced, when weighing the risk‐reducing effect of dummy use against the possible detrimental effect on breastfeeding, is that cases of SIDS are rare in the first two weeks of life. It is true that the incidence peaks later, around two months of age, but a Swedish study of 128 SIDS cases between 2005 and 2010 showed that 6.3% had occurred in the first 14 days and 18% in the first month of life 59. This poses a problem about the ideal time for introducing a dummy, which cannot be solved by general guidelines and must be decided individually for each mother–infant pair.

Shortcomings of the included studies

This review is mainly based on observational studies, but five RCTs have been conducted concerning the relationship between dummies and breastfeeding.

Randomised controlled studies are the gold standard in causal inference, but noncompliance and other protocol violations can reduce their value, which to some extent is the case with the RCTs in this review. This is, of course, due to the nature of the relationship studied. However, at least it is possible to conduct an RCT on the relationship between dummies and breastfeeding. Studying SIDS by randomising dummy use or breastfeeding would be highly unethical. In these cases, we are compelled to rely on evidence from observational studies, even though they are prone to issues like reverse causation and other misinterpretations of causality. Hill's criteria may be of some use in these situations, but even they do not set sharp lines between causation and noncausation 60.

Conclusion

We found scientific evidence that both breastfeeding and dummy use have a risk‐reducing effect on sudden infant death syndrome. The most recent studies available at the time of this review showed that dummy use might not be as harmful to breastfeeding as previously believed.

References

- 1. Wennergren G, Alm B, Øyen N, Helweg Larsen K, Milerad J, Skjaerven R, et al. The decline in the incidence of SIDS in Scandinavia and its relation to risk‐intervention campaigns. Nordic Epidemiological SIDS Study. Acta Paediatr 1997; 86: 963–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siwe S. Unerwarteter und plötzlicher Tod im Kindesalter in klinischer Beleuchtung [Sudden and unexpected death in infancy in a clinical lighting]. Upsala Lakareforen Forh [Ann Med Soc of Upsala] 1934; 39: 203–56. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hauck FR, Thompson JM, Tanabe KO, Moon RY, Vennemann MM. Breastfeeding and reduced risk of sudden infant death syndrome: a meta‐analysis. Pediatrics 2011; 128: 103–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fleming PJ, Blair PS, Ward Platt M, Tripp J, Smith IJ. Sudden infant death syndrome and social deprivation: assessing epidemiological factors after post‐matching for deprivation. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2003; 17: 272–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mitchell EA, Taylor BJ, Ford RP, Stewart AW, Becroft DM, Thompson JM, et al. Dummies and the sudden infant death syndrome. Arch Dis Child 1993; 68: 501–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mitchell EA, Scragg R, Stewart AW, Becroft DM, Taylor BJ, Ford RP, et al. Results from the first year of the New Zealand cot death study. N Z Med J 1991; 104: 71–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mitchell EA, Stewart AW, Scragg R, Ford RP, Taylor BJ, Becroft DM, et al. Ethnic differences in mortality from sudden infant death syndrome in New Zealand. BMJ 1993; 306: 13–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ford RP, Taylor BJ, Mitchell EA, Enright SA, Stewart AW, Becroft DM, et al. Breastfeeding and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome. Int J Epidemiol 1993; 22: 885–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Klonoff‐Cohen HS, Edelstein SL, Lefkowitz ES, Srinivasan IP, Kaegi D, Chang JC, et al. The effect of passive smoking and tobacco exposure through breast milk on sudden infant death syndrome. JAMA 1995; 273: 795–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schellscheidt J, Ott A, Jorch G. Epidemiological features of sudden infant death after a German intervention campaign in 1992. Eur J Pediatr 1997; 156: 655–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. L'Hoir MP, Engelberts AC, van Well GT, McClelland S, Westers P, Dandachli T, et al. Risk and preventive factors for cot death in the Netherlands, a low‐incidence country. Eur J Pediatr 1998; 157: 681–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tanaka T, Kato N. Evaluation of child care practice factors that affect the occurrence of sudden infant death syndrome: interview conducted by public health nurses. Environ Health Prev Med 2001; 6: 117–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alm B, Wennergren G, Norvenius SG, Skjaerven R, Lagercrantz H, Helweg‐Larsen K, et al. Breast feeding and the sudden infant death syndrome in Scandinavia, 1992–95. Arch Dis Child 2002; 86: 400–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hauck FR, Herman SM, Donovan M, Iyasu S, Merrick Moore C, Donoghue E, et al. Sleep environment and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome in an urban population: the Chicago Infant Mortality Study. Pediatrics 2003; 111: 1207–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vennemann MM, Bajanowski T, Brinkmann B, Jorch G, Yucesan K, Sauerland C, et al. Does breastfeeding reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome? Pediatrics 2009; 123: e406–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ponsonby AL, Dwyer T, Kasl SV, Cochrane JA. The Tasmanian SIDS case–control study: univariable and multivariable risk factor analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1995; 9: 256–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gilbert RE, Wigfield RE, Fleming PJ, Berry PJ, Rudd PT. Bottle feeding and the sudden infant death syndrome [see comments]. BMJ 1995; 310: 88–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fleming PJ, Blair PS, Bacon C, Bensley D, Smith I, Taylor E, et al. Environment of infants during sleep and risk of the sudden infant death syndrome: results of 1993–5 case–control study for confidential inquiry into stillbirths and deaths in infancy. Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths Regional Coordinators and Researchers. BMJ 1996; 313: 191–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mitchell EA, Tuohy PG, Brunt JM, Thompson JM, Clements MS, Stewart AW, et al. Risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome following the prevention campaign in New Zealand: a prospective study. Pediatrics 1997; 100: 835–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Törö K, Sotonyi P. Distribution of prenatal and postnatal risk factors for sudden infant death in Budapest. Scand J Prim Health Care 2001; 19: 178–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen A, Rogan WJ. Breastfeeding and the risk of postneonatal death in the United States. Pediatrics 2004; 113: e435–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McVea KL, Turner PD, Peppler DK. The role of breastfeeding in sudden infant death syndrome. J Hum Lact 2000; 16: 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, Trikalinos TA, Lau J. A summary of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's Evidence Report on breastfeeding in developed countries. Breastfeed Med 2009; 4: S17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arnestad M, Andersen M, Rognum TO. Is the use of dummy or carry‐cot of importance for sudden infant death? [see comments]. Eur J Pediatr 1997; 156: 968–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fleming PJ, Blair PS, Pollard K, Platt MW, Leach C, Smith I, et al. Pacifier use and sudden infant death syndrome: results from the CESDI/SUDI case control study. CESDI SUDI Research Team. Arch Dis Child 1999; 81: 112–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. L'Hoir MP, Engelberts AC, van Well GT, Damste PH, Idema NK, Westers P, et al. Dummy use, thumb sucking, mouth breathing and cot death. Eur J Pediatr 1999; 158: 896–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McGarvey C, McDonnell M, Chong A, O'Regan M, Matthews T. Factors relating to the infant's last sleep environment in sudden infant death syndrome in the Republic of Ireland. Arch Dis Child 2003; 88: 1058–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vennemann MM, Findeisen M, Butterfass‐Bahloul T, Jorch G, Brinkmann B, Kopcke W, et al. Modifiable risk factors for SIDS in Germany: results of GeSID. Acta Paediatr 2005; 94: 655–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li DKWM, Petitti DB, Odouli R, Liu L, Hoffman HJ. Use of a dummy during sleep and risk of sudden infant death syndrome. Population based case–control study. BMJ 2006; 332: 18–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thompson JM, Thach BT, Becroft DM, Mitchell EA, New Zealand Cot Death Study G . Sudden infant death syndrome: risk factors for infants found face down differ from other SIDS cases. J Pediatr 2006; 149: 630–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moon RY, Tanabe KO, Yang DC, Young HA, Hauck FR. Pacifier use and SIDS: evidence for a consistently reduced risk. Matern Child Health J 2012; 16: 609–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hauck FR, Omojokun OO, Siadaty MS. Do pacifiers reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome? A meta‐analysis. Pediatrics 2005; 116: e716–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mitchell EA, Blair PS, L'Hoir MP. Should pacifiers be recommended to prevent sudden infant death syndrome? Pediatrics 2006; 117: 1755–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vogel A, Hutchison BL, Mitchell EA. Factors associated with the duration of breastfeeding. Acta Paediatr 1999; 88: 1320–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Riva E, Banderali G, Agostoni C, Silano M, Radaelli G, Giovannini M. Factors associated with initiation and duration of breastfeeding in Italy. Acta Paediatr 1999; 88: 411–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Aarts C, Hornell A, Kylberg E, Hofvander Y, Gebre‐Medhin M. Breastfeeding patterns in relation to thumb sucking and pacifier use. Pediatrics 1999; 104: e50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Howard CR, Howard FM, Lanphear B, deBlieck EA, Eberly S, Lawrence RA. The effects of early pacifier use on breastfeeding duration. Pediatrics 1999; 103: E33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vogel AM, Hutchison BL, Mitchell EA. The impact of pacifier use on breastfeeding: a prospective cohort study. J Paediatr Child Health 2001; 37: 58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marques NM, Lira PI, Lima MC, da Silva NL, Filho MB, Huttly SR, et al. Breastfeeding and early weaning practices in northeast Brazil: a longitudinal study. Pediatrics 2001; 108: E66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ingram J, Johnson D, Greenwood R. Breastfeeding in Bristol: teaching good positioning, and support from fathers and families. Midwifery 2002; 18: 87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Binns CW, Scott JA. Using pacifiers: what are breastfeeding mothers doing? Breastfeed Rev 2002; 10: 21–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Giovannini M, Riva E, Banderali G, Scaglioni S, Veehof SH, Sala M, et al. Feeding practices of infants through the first year of life in Italy. Acta Paediatr 2004; 93: 492–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nelson EA, Yu LM, Williams S. International Child Care Practices study: breastfeeding and pacifier use. J Hum Lact 2005; 21: 289–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Scott JA, Binns CW, Oddy WH, Graham KI. Predictors of breastfeeding duration: evidence from a cohort study. Pediatrics 2006; 117: e646–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Santo LC, de Oliveira LD, Giugliani ER. Factors associated with low incidence of exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months. Birth 2007; 34: 212–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kronborg H, Vaeth M. How are effective breastfeeding technique and pacifier use related to breastfeeding problems and breastfeeding duration? Birth 2009; 36: 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Feldens CA, Vitolo MR, Rauber F, Cruz LN, Hilgert JB. Risk factors for discontinuing breastfeeding in southern Brazil: a survival analysis. Matern Child Health J 2012; 16: 1257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Karabulut E, Yalcin SS, Ozdemir‐Geyik P, Karaagaoglu E. Effect of pacifier use on exclusive and any breastfeeding: a meta‐analysis. Turk J Pediatr 2009; 51: 35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schubiger G, Schwarz U, Tonz O. UNICEF/WHO baby‐friendly hospital initiative: does the use of bottles and pacifiers in the neonatal nursery prevent successful breastfeeding? Neonatal Study Group. Eur J Pediatr 1997; 156: 874–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kramer MS, Barr RG, Dagenais S, Yang H, Jones P, Ciofani L, et al. Pacifier use, early weaning, and cry/fuss behavior: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 286: 322–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Howard CR, Howard FM, Lanphear B, Eberly S, deBlieck EA, Oakes D, et al. Randomized clinical trial of pacifier use and bottle‐feeding or cup feeding and their effect on breastfeeding. Pediatrics 2003; 111: 511–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Collins CT, Ryan P, Crowther CA, McPhee AJ, Paterson S, Hiller JE. Effect of bottles, cups, and dummies on breast feeding in preterm infants: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2004; 329: 193–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jenik AG, Vain NE, Gorestein AN, Jacobi NE. Does the recommendation to use a pacifier influence the prevalence of breastfeeding? J Pediatr 2009; 155: 350–4.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jaafar SH, Jahanfar S, Angolkar M, Ho JJ. Pacifier use versus no pacifier use in breastfeeding term infants for increasing duration of breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 16: CD007202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Helweg‐Larsen K, Lundemose JB, Oyen N, Skjaerven R, Alm B, Wennergren G, et al. Interactions of infectious symptoms and modifiable risk factors in sudden infant death syndrome. The Nordic Epidemiological SIDS study. Acta Paediatr 1999; 88: 521–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Duijts L, Ramadhani MK, Moll HA. Breastfeeding protects against infectious diseases during infancy in industrialized countries. A systematic review. Matern Child Nutr 2009; 5: 199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tonkin SL, Lui D, McIntosh CG, Rowley S, Knight DB, Gunn AJ. Effect of pacifier use on mandibular position in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr 2007; 96: 1433–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Horne RS, Hauck FR, Moon RY, L'Hoir MP, Blair PS, Physiology and Epidemiology Working Groups of the International Society for the Study and Prevention of Perinatal and Infant Death . Dummy (pacifier) use and sudden infant death syndrome: potential advantages and disadvantages. J Paediatr Child Health 2014; 50: 170–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Möllborg P, Wennergren G, Almqvist P, Alm B. Bed sharing is more common in sudden infant death syndrome than in explained sudden unexpected deaths in infancy. Acta Paediatr 2015; 104: 777–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med 1965; 58: 295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]