Abstract

Patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) may not be optimally treated. The impact of the disease extends beyond skin and joint symptoms, impairing quality of life. This indicates that the adoption of a patient‐focused approach to PsA management is necessary. An expert multidisciplinary working group was convened, with the objective of developing an informed perspective on current best practice and needs for the future management of PsA. Topics of discussion included the barriers to current best practice and calls to action for the improvement of three areas in PsA management: early and accurate diagnosis of PsA, management of disease progression and management of the impact of the condition on the patient. The working group agreed that, to make best use of the available of diagnostic tools, clinical care recommendations and effective treatments, there is a clear need for healthcare professionals from different disciplines to collaborate in the management of PsA. By facilitating appropriate and rapid referral, providing high quality information about PsA and its treatment to patients, and actively involving patients when choosing management plans and setting treatment goals, management of PsA can be improved. The perspective of the working group is presented here, with recommendations for the adoption of a multidisciplinary, patient‐focused approach to the management of PsA.

Introduction

Despite the existence of evidence‐based screening instruments, diagnostic tools and treatment recommendations, patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) may not be receiving optimal treatments.1 Whether PsA is diagnosed depends, in part, on whether a general practitioner (GP) or dermatologist has the specific knowledge and skill to recognize the symptoms and promptly refer the patient to a rheumatologist. A delay in treatment of PsA after diagnosis can result in an increased rate of progression of clinical damage,2 and quality of life (QoL) can be negatively affected, with patients experiencing pain,3 fatigue4 and depression.5 The impact of PsA beyond joint and skin symptoms strongly indicates that a patient‐focused approach should be emphasized in the management of PsA.6

With this in mind, a multidisciplinary working group comprising clinicians, academics and representatives of patient advocacy groups (PAGs) contributed to a virtual summit meeting to define and agree upon the actions they believe to be helpful to improve standards of care for patients with PsA in Europe.

Methods

Seven participants were invited from a variety of specialities (dermatology, rheumatology, behavioural medicine, patient advocacy) to form a multidisciplinary working group. The working group convened via a closed online forum (virtual meeting), with the objective of discussing unmet patient needs in PsA. A specific body of literature and area of practice was assigned to each member of the group, who posted to the forum their professional perspectives and opinions on the unmet needs and best practice in the treatment of patients with PsA in Europe. The forum remained open for 4 months in 2013, during which time the working group was able to freely discuss the content.

The key topics addressed included the early and accurate diagnosis of PsA, the effective management of disease progression, and how best to reduce the impact of PsA on an individual's life. The group also agreed on specific calls to action to improve clinical practice in the patient‐focused management of PsA. The final opinions and perspectives of the group are presented here, supplemented with information from the literature.

Overcoming barriers to the early and accurate diagnosis of PsA

Patients with PsA suffer from stiffness, pain, swelling and joint damage leading to increased disability;7 however, there is not necessarily an observable pattern or distinctive timing of symptoms associated with PsA that is common to all patients. Up to 30% of patients with psoriasis also develop PsA, with skin symptoms typically preceding joint problems.2, 8 Though no absolute indicators have been identified to predict that a person with psoriasis may develop PsA, the presence of soluble biomarkers, for example, highly sensitive C‐reactive protein (hsCRP), osteoprotegerin (OPG), matrix metalloproteinase‐3 (MMP‐3) and the C‐propeptide of type II collagen to collagen fragment neoepitopes Col2‐3/4long mono ratio or certain susceptibility genes (e.g. certain human leucocyte antigen alleles [HLA‐B and HLA‐C]) may confer susceptibility to PsA among patients with psoriasis.9, 10, 11, 12 Moreover, the predictive nature of clinical observations such as the severity of psoriasis (as measured by the Psoriasis Area Severity Index [PASI]), the severity of joint involvement and the presence of certain psoriasis features (e.g. scalp lesions, nail disease and intergluteal/perianal psoriasis) with respect to the risk of developing PsA remains unclear.10, 13, 14, 15 Determining such absolute indicators for PsA remains complicated because of varying study designs (e.g. prospective vs. observational studies) and by potential differences in the clinical observations made by patients being managed by dermatologists vs. rheumatologists. A patient with psoriasis who does not report new symptoms consistent with PsA, or a healthcare professional (HCP) who does not recognize the symptoms of PsA, may inadvertently delay the diagnosis.

It is difficult to achieve early diagnosis of PsA in the absence of characterized disease biomarkers or a definitive screening procedure. Simple and validated screening tests, such as the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) tool, the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST), the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen (ToPAS) and the Early ARthritis for Psoriatic patients (EARP) questionnaire, have been assessed to determine whether people with suspected PsA should be referred to confirm the diagnosis (Table 1).16, 17, 18, 19 Despite such tools, the paucity of data from secondary care regarding their feasibility, sensitivity and specificity, along with the lack of consensus on which tool is best, hampers their widespread clinical use. In some cases the sensitivities and specificities of the tools have been found to be lower than originally reported; when the PASE, PEST and ToPAS questionnaires were compared in the CONTEST study, it was found that they would identify cases of musculoskeletal disease other than PsA, and there was little difference between the performance of the tools.20

Table 1.

Screening tools for people with suspected PsA

| Tool | Users | Usage setting | Objectives | Further notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE)16 | Dermatologists | Secondary care |

• For assessment of likely joint symptoms in patients with psoriasis, and directing referral to rheumatologist • Assessment of the impact of symptoms on the patient, in terms of disability |

• Can distinguish between PsA subtypes • Can distinguish between PsA and osteoarthritis |

| Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST)18 | GPs, hospital clinicians | Community setting and hospital clinic | • Detection of PsA in patients with existing psoriasis | • Uses a diagram or a mannequin to allow patients to identify location of symptoms |

| Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen (ToPAS)17 | GPs, dermatologists, rheumatologists | Primary and secondary care | • Identification of PsA in patients with existing psoriasis or in general population | • Uses images of skin/nail involvement for screening |

| Early ARthritis for Psoriatic patients (EARP)19 | Dermatologists, rheumatologists | Secondary care | • Early identification of PsA in patients with existing psoriasis | • Simpler and faster than PASE |

In addition to the use of these tools, rheumatologists need to share their expertise with dermatologists, to improve understanding of the clinical spectrum of PsA among dermatologists and to facilitate decisions about referral.

For an accurate diagnosis to be made, it is important that people with suspected PsA are referred to a rheumatologist. Several factors can slow the referral process.6 A lack of awareness of the clinical spectrum of PsA by GPs, compounded by short consultation appointments that prevent a thorough clinical examination, is a key contributor here. Even if symptoms are apparent, a GP who lacks specific knowledge about psoriasis and PsA may not recognize the seriousness of the condition. This may also be true of dermatologists if they are unfamiliar with the symptoms of PsA, since a patient is unlikely to be referred to a rheumatologist unless a specific request is made.

Inappropriate referral is also a potential issue; while it is likely that a patient with polyarthritis will be correctly referred, non‐rheumatologists may not be aware that PsA may present with inflammatory back pain (axial symptoms), enthesitic pain, tenosynovitis, dactylitis and/or large joint arthritis of the lower limbs with scarce inflammatory features. Consequently, patients may initially be referred for an orthopaedic opinion or to a physiotherapist, rather than a rheumatologist.

Patients may unknowingly present a barrier to their own diagnosis. If a person with psoriasis is not aware of the relevance of joint symptoms, he or she may not report them to a dermatologist. Equally, a person may attribute symptoms such as pain or fatigue to causative factors other than PsA. In addition, despite clinically confirmed joint inflammation and damage, patients with PsA appear to have higher thresholds for joint tenderness than patients with rheumatoid arthritis with similar levels of joint inflammation, further compounding the under‐recognition of their symptoms.21

Delayed diagnosis can have a substantial impact on patients with PsA. As with any long‐term medical condition, early diagnosis helps to avoid extended periods of untreated disease, unnecessary examinations and the use of potentially ineffective treatment. One study of patients with PsA who fulfilled ClASsification of Psoriatic ARthritis (CASPAR) criteria with an average disease duration of more than 10 years found that even a 6‐month delay from symptom onset to the first visit to a rheumatologist contributed to the development of peripheral joint erosions and worse long‐term physical function.22

Recommendations on best practice

To overcome the barriers to early and accurate diagnosis of PsA, awareness of the condition must be raised and management pathways clearly defined. Ideally, dermatologists and GPs should be familiar with the signs and symptoms of PsA; at the very least they should be aware that PsA is a common problem among patients with psoriasis, be able to differentiate between inflammatory and non‐inflammatory joint pain and be aware of the appropriate referral pathway.23 It is important to recognize that PsA is a multisystemic disease, to make HCPs aware of the possibility of the recurrence of PsA among patients with psoriasis, and to make screening for PsA standard practice. Early and regular screening, including validated measures of patient symptoms and with attention to joint symptoms, would help move towards the ideal situation that no patient with psoriasis would have their PsA unrecognized and, if it were to develop during the course of their life, they would receive appropriate treatment as soon as required. As soon as PsA is suspected, the patient should be referred to a rheumatologist for assessment and advice about planning their care.23, 24 In the UK, guidelines issued by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend that annual assessments for PsA should be offered to people with any type of psoriasis.24 Moreover, although NICE considers assessment to be especially important within the first 10 years of onset of psoriasis,24 evidence from a cross‐sectional study25 and prospective studies26, 27 indicate that the risk for developing PsA remains constant after the initial diagnosis, leading to a higher prevalence of concomitant PsA with time.

Interaction between rheumatologists and dermatologists can facilitate the formation of multidisciplinary units for the management of complex cases. A 4‐year study of the implementation of a multidisciplinary psoriasis and PsA unit improved both the collaboration between dermatologists and rheumatologists and the early diagnosis and treatment of PsA.27, 28

Patients with psoriasis need to be made aware of the risks of developing PsA and its long‐term consequences through effective patient education at the time of diagnosis. Patients should understand that PsA can occur at any time during the course of psoriasis, there is no known trigger and the presence of PsA does not involve greater severity of skin psoriasis. Also, patients should be reassured that although PsA is not a curable disease, in most cases it is treatable. Patients need to be encouraged to record and then communicate their skin and joint symptoms to their HCP. This information can help the HCP make a rapid and appropriate referral, helping to ensure a timely and accurate diagnosis by the rheumatologist.

At the first consultation with the rheumatologist, during which the diagnosis is established, disease information is essential. Small amounts of relevant information given over time, in combination with goal setting and action planning, will help the patient to accept the diagnosis, maintain motivation to self‐manage and remain adherent to management plans. Patient engagement and activation at the outset are essential and a self‐management programme based on psychological principles that includes addressing patients' beliefs will be more beneficial than supplying information and relying on the patient to digest, remember and understand it.29 The patient should be empowered to request information about any points that they do not understand about their disease or treatment, standards of care, pathways for referral and collaboration between specialists of different disciplines. By engaging with patients with suspected PsA, PAGs can assist by providing relevant and targeted information about the signs and symptoms of PsA and when to alert the dermatologist.

Calls to action: improving early and accurate diagnosis

Health authorities and academic societies should create educational awareness campaigns aimed at GPs and dermatologists about the symptoms of PsA to improve understanding of the disease.

HCPs should regularly screen psoriasis patients for signs and symptoms of PsA.

GPs, dermatologists and rheumatologists should coordinate their efforts to ensure patients are referred in an appropriate and timely fashion, and that treatment of the patient is not restricted to only the skin and joints.

Rheumatologists should implement head‐to‐head studies of the screening tools for PsA to help define their usage and application and drive their refinement.

PAGs should support and help to run educational programmes to help patients recognize symptoms of PsA and actively seek referral to a rheumatologist.

Soon after diagnosis, HCPs and PAGs should provide information to patients with PsA to help inform their understanding of the natural course of disease, including long‐term joint damage, as well as the benefits of available treatments.

Patients should be offered support from suitably qualified personnel to assist with self‐management and address distress resulting from PsA.

Addressing the challenges to the effective management of PsA disease progression

A survey of more than 5000 patients with psoriasis and PsA, conducted by the National Psoriasis Foundation in the US between 2003 and 2011, revealed that 46% of those with PsA are dissatisfied with their treatment.30 This suggests that new options and approaches to PsA management are necessary.30

The main challenges to effective long‐term management of PsA are the control of structural damage to bone and cartilage and the preservation or enhancement of QoL. Structural damage, both axial and peripheral, is the variable that best correlates with long‐term disability.31 However, tools designed to specifically assess structural damage are currently lacking and most have been adapted from other rheumatic musculoskeletal diseases.

In recent years, the availability of highly effective treatments such as biological therapies has led to the use of treat‐to‐target strategies.32 While recommendations for such an approach with rheumatoid arthritis have been developed,33 adopting a treat‐to‐target strategy for PsA presents a greater challenge for a number of reasons:34 the heterogeneous presentation of PsA, the scarcity of data to support the treatment of PsA to a target, and a lack of definitions of the specific criteria for remission of PsA.32 The TIght Control of Psoriatic Arthritis (TICOPA) trial has shown that a treat‐to‐target approach in patients with newly diagnosed PsA can significantly improve joint outcomes. Patients randomized to tight control (using methotrexate, combination disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs [DMARDs] and antitumour necrosis factor drugs) had a greater chance of achieving an American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20 response at 48 weeks than patients treated with standard care. Although more adverse events were seen in the tight control group, no unexpected serious adverse events were seen.35 While adherence to a treat‐to‐target strategy may improve outcomes, the specifics and feasibility of employing such a protocol in widespread clinical practice requires further investigation.

Even when the most appropriate management plan is initiated, a person with PsA might not adhere to it. Patients may hold unhelpful or erroneous beliefs about the cause, consequences, control and timeline of the condition and/or the medical interventions prescribed. Anxiety and depression, conditions associated with PsA,36 can lead to low adherence in chronic disease,37 and a low sense of confidence or ability of the patient to self‐manage. Overly complex medication regimens may also impair adherence,38 particularly if the patient does not understand the need for each component or is concerned about unwanted effects.

While a multidisciplinary approach might be the most attractive option for the care of patients with PsA, imbalances between the numbers of rheumatologists and dermatologists may result in difficulties when trying to develop pan‐European recommendations for referral and management.6 For instance, in a country with relatively few rheumatologists, they are likely to share their time between patients with a range of inflammatory musculoskeletal diseases, and may not be able to dedicate a large amount of it to PsA patients.

Finally, there are financial and political barriers to effective PsA management. Patients with PsA incur substantial direct and indirect costs of illness, and are significant users of healthcare resources through regular visits to GPs and specialists, and also hospitalization.39 The Norwegian DMARD register indicates that, for treatment of PsA, 6‐month direct costs (including drug costs and patient care) for synthetic and biological DMARDs can reach €1795 and €11 317, respectively, although these costs can decline as treatment proceeds.40 Indirect costs (mainly productivity losses) for a 6‐month period can reach €15 552 and €20 762 for synthetic and biological DMARDs, respectively.40 Because psoriasis and PsA are long‐term conditions, consistent and repeated costs can accumulate quickly. If a country's health authority does not recognize psoriasis and PsA as lifelong debilitating conditions, or offer appropriate reimbursement, then the patient's access to treatment may be limited.

Recommendations on best practice

Multiple evidence‐based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of PsA have been developed for use throughout Europe, including European‐level statements, national guidelines and recommendations (Table 2). For example, the recommendations for best practice in the treatment of PsA developed by GRAPPA are a survey of the best available evidence and the consensus of an international group of rheumatologists and dermatologists.41 Their recommendations differentiate between the treatment of peripheral and axial arthritis, enthesitis, skin and nails, and dactylitis. Advice is also given on grading disease severity to aid decision‐making. EULAR (the European League Against Rheumatism) has also established and published recommendations for the management of PsA, which are based on best available evidence and current expert opinion, including that of patients.42

Table 2.

Evidence‐ and consensus‐based recommendations for diagnosis and management of PsA

| Region/country | Group/society involved in the development of the recommendations | Year of issue | Audience |

|---|---|---|---|

| International | Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA)41 | 2009 | All clinicians caring for patients with PsA |

| International | The Psoriatic Arthritis Forum60 | 2014 | Rheumatologists |

| European | European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)42 | 2012 | Those affected by PsA or those involved in the management of PsA |

| European | Working group of dermatologists and a rheumatologist59 | 2014 | Rheumatologists and dermatologists |

| French | French Society for Rheumatology61 | 2007 | Rheumatologists |

| Italy | Italian Society for Rheumatology62 | 2011 | Rheumatologists |

| Portugal | Portuguese Society of Rheumatology63 | 2012 | Rheumatologists |

| Spain | Spanish Society of Rheumatology64 | 2011 | Rheumatologists |

| UK | British Society of Rheumatology65 | 2012 | Rheumatologists and prescribing clinicians |

| National Institute for Health and Care Excellence24 | 2012 | All clinicians caring for patients with psoriasis and/or PsA |

Although guidelines and recommendations are crucial to inform good practice, the needs of the patient should always be at the forefront of clinical decisions. Following prompt referral and diagnosis, it is important to explain the characteristics of the disease. A clear and simple management plan should be decided upon with the patient using shared decision‐making tools and techniques, individualized according to their symptoms and predominant pattern of disease, defining treatment goals, initiation, adaptation and follow‐up. Patients' preferences and expectations should be considered, and their current level of knowledge on the condition and what they want from services and specialists should be established. Improving a patient's knowledge of the disease and the treatment available can improve treatment adherence.43 With the objective of maximizing adherence, consultations should include information on mood, lifestyle, level of disability and therapeutic goals. The long‐term effects of PsA and other future issues should be discussed, and patients should be informed about any national or regional PAGs that can offer further information and support. Positive steps should be taken to address a patient's beliefs about PsA and the associated treatment, as these can have a bearing on adherence to a management plan.

Patient evaluations should be repeated depending on disease severity and response to treatment, but during the first 2 years they should be performed every 2–6 months to assess treatment response. Depending on the outcome of these assessments, treatment modification might be considered according to the achievement or failure to achieve the planned therapeutic objectives. Patients should be encouraged to take an active role, through self‐assessment and reporting back to the rheumatologist at regular appointments. The variables to be assessed should be relevant to the disease pattern of PsA and should also include the evaluation of skin disease and the detection of possible co‐morbidities (such as metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease or impaired liver function); lifestyle and personal factors (such as mood, smoking and alcohol intake) may also influence the choice of therapy. Medications used to control existing co‐morbidities may need to be considered when choosing a treatment plan. Regular examination and re‐evaluation of the management plan should help patients with PsA to achieve the best outcomes. A series of key questions to pose to people with suspected PsA, or in whom PsA has been diagnosed but progression needs to be followed, has been published previously by Radtke et al.44

In the Swedish Early Psoriatic Arthritis Register, a study with 5‐year follow‐up, recognition of PsA soon after the onset of symptoms was one of the important predictors of favourable clinical outcomes; prompt active treatment was also considered important.45 Furthermore, early diagnosis and treatment of PsA with a DMARD may reduce joint damage compared with later initiation of treatment;22 better outcomes have been associated with initiation of therapy within 2 years of onset of PsA, compared with 2 years after onset.46

As treatment with a DMARD can lead to the improvement of QoL,47 the positive effects of early treatment may extend beyond the clinical outcomes.

Increasing patients' understanding of PsA is important, but can be challenging, and requires the active involvement of a number of parties (Table 3). One such party are PAGs, which play an important role at both the national and European level to enhance the availability of care. For example, the Brussels Declaration, a document developed by EULAR, summarizes the needs, wishes and declared rights of people living with all forms of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (including PsA).48 Since its presentation at a meeting of health ministers from every country in the EU in October 2010, many Members of the European Parliament have signed up to support the statement. Presentation of the Brussels Declaration in Bulgaria and Serbia has led to enhancements in healthcare for patients with rheumatic disease, including improvement in access to biological treatments. Collaborative campaigning by pan‐European research groups, academic institutions and several PAGs has contributed to rheumatic diseases being given a priority status in the subsequent EU Research Framework programme, Horizon 2020. As a result, rheumatic disease is currently named alongside cancer and diabetes as a major condition in terms of research.

Table 3.

Increasing disease awareness amongst patients

| Influencer | Role in increasing patient awareness | Barriers to increasing patient awareness |

|---|---|---|

| Dermatologist/GP | To inform patients about the characteristics and consequences of their disease in a timely and appropriate way, before referral to the rheumatologist |

• Lack of HCP disease education (signs and symptoms, disease burden, referral process, etc.) • Lack of early detection campaigns • Lack of multidisciplinary units for the management of PsA |

| Specialist nurse | To assist specialists, promote communication within the multidisciplinary team and help patients understand their treatment regimens including administration, medication type, monitoring requirements, side effects, misuse, etc |

• Do not exist/are not deployed in all countries • Appropriate training required |

| Medical societies | To serve as an up‐to‐date resource for information about PsA | • Lack of patient awareness that medical societies are a source of information |

| PAGs | To provide information covering practical issues (e.g. lifestyle and diet) from the perspective of the patient | • Requires multidisciplinary collaboration between PAGs, rheumatologists and dermatologists |

Consensus among experts is that PsA demands a collaborative approach between rheumatologists and dermatologists since the majority of people with PsA have existing psoriasis. The nature of such a collaboration will naturally depend on national healthcare systems. Clinical decision‐making must take into account all domains of the disease and the patient should be an active member in developing their treatment plan.41, 42

Calls to action: improving the effective management of PsA

HCPs should be aware of and implement evidence‐based guidelines and recommendations for the diagnosis and management of PsA to optimize treatment of their patients as early as possible in the course of disease.

Academic societies that have developed evidence‐based guidelines and recommendations should review and update them on a regular basis, consulting patients and/or PAGs to ensure an emphasis on patient‐focused care.

HCPs should work together to design, develop and validate new tools specifically designed to assess PsA in terms of joint damage.

Industry and HCPs should continue to undertake clinical research and initiate PsA registries to determine the long‐term risks and benefits of drugs currently used for the treatment of PsA, to define treatment targets for PsA and to evaluate the risks and benefits of intensive treat‐to‐target therapy in comparison to current standards of care.

- Dermatologists, rheumatologists, psychologists, specialist nurses and PAGs should collaborate to adopt an individualized, multidisciplinary approach to the care of patients with PsA.

- To inform and drive the establishment of multidisciplinary teams, clinics and hospitals in which a successful collaboration has been forged should share best practice on how this was achieved and maintained, and the outcomes for patients.

- HCPs and PAGs should collaborate to develop and distribute high quality information to patients with PsA, enabling them to clearly understand and communicate their current disease status.

Patients should be encouraged and empowered to take an active role in setting individualized, achievable therapeutic goals and choosing an appropriate management plan, with access to a range of treatments.

Mitigating the impact of PsA on the patient

In comparison with the general population, patients with PsA have higher co‐morbidity scores, with the most prevalent co‐morbidities reported being hypertension, heart diseases, chronic respiratory diseases and gastrointestinal conditions.49 An elevated risk of cardiovascular disease is also known to occur in psoriasis,50 and is responsible for 20–56% of deaths in patients with PsA.51 Alongside high disease activity, the presence of co‐morbidity has been found to impact health‐related QoL (HRQoL) in patients with PsA.49 Moreover, patients with PsA can have a significantly lower HRQoL than the general population.39, 49

As assessed by the Short Form 36‐item Health Survey Questionnaire (SF‐36), a widely used example of a generic health profile, significant impairments have been observed across all eight of the domains of HRQoL, including physical and social functioning and mental health, in patients with inflammatory rheumatic disease, including PsA, indicating that it is sensitive for use in the PsA population.49 In addition to the impact found on physical functioning, poor mental functioning was associated with the severity of psoriatic lesions.49

Studies assessing patients' opinions about their health condition, which reflect the patient burden of disease, are limited in PsA. Published trials assessing patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) have largely focused on a core set of domains including pain, patient global assessment, physical function and HRQoL using either generic tools or those that have been adapted from rheumatoid arthritis. As such, other dimensions of health may be important in PsA. With the support of EULAR the PsA Impact of Disease (PsAID) questionnaire, a focused tool for assessing PROMs in patients with PsA, has recently been developed and validated.4

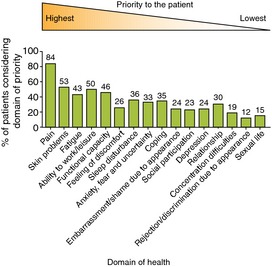

Two questionnaires were developed, one for clinical trials and one for clinical practice. Of 16 domains of health, pain, fatigue and skin problems had the highest relative importance as identified by 139 patients with PsA (Fig. 1). Pain of varying degree is a common occurrence in all types of arthritis. In a survey conducted by the UK charity Arthritis Care of 2263 people with all types of arthritis (8% of whom had a diagnosis of PsA), 35% experienced some form of pain (mild to severe pain) and 32% of respondents said that their everyday pain was often unbearable and frequently stopped them from doing daily activities.3

Figure 1.

Sixteen domains of health were identified as important by 12 patients with PsA; the proportion of 139 patients considering each domain a priority is shown. The domains are ranked according to median order of importance (range of importance 1–16). Adapted from Gossec et al.4

Fatigue, which was identified by the PsAID questionnaire as important in patients with PsA,4 is commonly experienced in patients with PsA. In a Canadian study, half of all patients with PsA reported moderate fatigue and 29% reported severe fatigue.52 A combination of pain, fatigue and anxiety can result in a vicious cycle, worsening the symptoms and impact of PsA and psoriasis. Patients may report reduced activity, resulting in poor physical fitness due to a combination of joint pain and fatigue. Lack of sleep and unwanted effects of medication may cause irritability, and with low energy levels patients may withdraw from favoured activities. A cross‐sectional study that included 83 patients with PsA showed an incidence of moderate to severe levels of depressive symptoms in 22% of the cohort.5 Anxiety and concern about bodily symptoms were also seen to affect HRQoL.5 Taken together, these factors will negatively influence interpersonal and family relationships, and can contribute to work absenteeism and hence affect career prospects; however, further high quality research is needed to determine the extent of this effect.

Not only does PsA affect a patient's QoL, but it can also have an economic impact on society.39 In addition to the direct costs of PsA management, lost productivity can result from increased disability and the significantly lower employment of patients with PsA, compared with the general population.39, 53 Close to one‐third of patients with PsA may also make short‐term or permanent disability claims, costs for which increase substantially with duration of disease.39

Recommendations on best practice

Assuming PsA is correctly diagnosed and effectively managed, the first step in helping to reduce the impact on the patient must be to fully understand how the disease affects them. For instance, in the UK, NICE guidelines recommend that people with any type of psoriasis (which should extend to PsA) should be assessed for the impact of disease on physical, psychological and social well‐being to formulate an appropriate intervention.24 More and better quality studies are required to determine the nature of the association between severity of symptoms and psychological impact.

Despite being an important objective in the long‐term treatment of PsA, QoL continues to be a variable that is seldom considered for therapeutic aims. Although the generic SF‐36 questionnaire, reflective of overall QoL, can be applied, a specific QoL measure that encompasses both skin and articular disease would be preferred, since they each contribute in an additive manner to the disability and worsening of mood in patients. The development and validation of new tools, centred on HRQoL and patient‐reported outcomes, such as those identified in the VITACORA and PsAID questionnaires,4, 54 should help strengthen data from clinical trials and aid clinical management in terms of the impact of the disease on the patient.

For the results to be used effectively, QoL measures should be deployed correctly. The SF‐36 questionnaire may be administered effectively by an interviewer with appropriate training, and the PsAID questionnaire, which deals with psychological aspects of disease burden, is an easy self‐reported questionnaire.54 Dermatologists and rheumatologists should not assume that nursing staff do or can provide this support without training. Therefore, an assessment of psychological functioning should be considered as part of the full assessment, although this is not realistic in all cases. When assessing a patient with PsA, a psychologist may choose to forfeit a QoL measure in favour of a more specific illness beliefs and distress measure, as these tools help to better formulate an intervention. The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) are both appropriate for this purpose. When beliefs are targeted and patients assisted in setting meaningful disease management goals, it is likely that QoL will be improved.

Although not trialled in PsA specifically, cognitive behavioural therapy has shown efficacy in improving psychological functioning in other long‐term conditions, including psoriasis.55, 56 Such an intervention aims to address beliefs, help mood management and improve QoL, but further research is required to determine the acceptability of this approach and its applicability in PsA specifically.57

Calls to action: easing the impact of PsA for the patient

PsA needs to be universally recognized as a multifactorial, long‐term and debilitating condition that can cause significant physical and psychological impairment and reduction in QoL.

Clinical trials of drugs for the treatment of PsA should collect patient‐reported outcomes and QoL data, to supplement efficacy and safety data.

An integrated psychological approach to clinical management should be adopted for patients with PsA.

Patients should be referred for psychological assessments when needed; e.g. at diagnosis, when the disease progresses or when treatment changes.

PAGs should continue to actively participate in meetings of groups that develop guidelines and recommendations, to provide the patient perspective of the psychosocial burden of PsA and to outline the support required.

PAGs should engage with governments and health authorities to raise awareness of the burden associated with PsA and ensure that its burden is addressed in future policies.

Conclusions and future perspectives

Despite the availability of diagnostic tools, effective treatments and supportive infrastructure, patients with PsA are still not receiving the optimal level of care. This review has presented a series of considerations for improvement of the level of care for patients with PsA.

There are many ways in which to improve patient outcomes in PsA, but the requirement for the involvement of more than one healthcare discipline can complicate planning and execution. If dermatologists and rheumatologists agree a process for collaboration, ask patients the right questions and ensure that patients are fully engaged, time to diagnosis could be significantly reduced and appropriate treatment delivered sooner. A previous initiative that presented strategies for the improvement of care for people with psoriasis, the European Psoriasis White Paper, took a similar approach to that described here to engage with the multiple stakeholders who have responsibility for improving patient care.58

While cooperation between dermatologists and rheumatologists has been proposed before,59 a fully integrated and collaborative approach between dermatologists, rheumatologists, specialist nurses, psychologists, patients and PAGs would build understanding of PsA and its impact on the patient and optimize its management.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ronan Farrelly (EUROPSO) for his valuable input to the development of this manuscript. Editorial assistance was provided by David Jenkins of Publicis Life Brands Resolute, London, UK.

Conflicts of interest

Neil Betteridge has not been reimbursed for any other work by the company that provided funding to support the work of this project. Wolf‐Henning Boehncke has received honoraria as a consultant or speaker on the occasion of company‐sponsored symposia from AbbVie, Biogen Idec, Celgene, Covagen, Janssen, Leo, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pantec Biosolutions, Pfizer and UCB. Christine Bundy has received honoraria for presenting from AbbVie, Janssen, Pfizer and Novartis, and has received a research grant from Pfizer. Laure Gossec has received speaking fees or honoraria (<10 000 Euro each, unrelated to the present work) from Abbott/AbbVie, Celgene, Chugai, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. Jordi Gratacós has received fees for speaking and/or consulting from AbbVie, Janssen, MSD, Celgene, Pfizer and UCB. Matthias Augustin has worked as an advisor and/or presenter and/or participant at clinical studies for the following companies: Abbott/AbbVie, Almirall‐Hermal, Amgen, Biogen Idec, Celgene, Centocor, Janssen‐Cilag, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Medac, MSD (previously Essex, Schering‐Plough), Novartis and Pfizer (previously Wyeth).

Funding sources

Financial assistance for the virtual summit meeting and writing support was provided by Janssen Pharmaceutica NV.

References

- 1. Reich K, Kruger K, Mossner R, Augustin M. Epidemiology and clinical pattern of psoriatic arthritis in Germany: a prospective interdisciplinary epidemiological study of 1511 patients with plaque‐type psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2009; 160: 1040–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gladman DD, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Cook RJ. Do patients with psoriatic arthritis who present early fare better than those presenting later in the disease? Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70: 2152–2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arthritis Care . Arthritis hurts. The hidden pain of arthritis. 2010. 27‐9‐2013.

- 4. Gossec L, de Wit M, Kiltz U, Braun J, Kalyoncu U, Scrivo R et al A patient‐derived and patient‐reported outcome measure for assessing psoriatic arthritis: elaboration and preliminary validation of the Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease (PsAID) questionnaire, a 13‐country EULAR initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 1012–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kotsis K, Voulgari PV, Tsifetaki N, Machado MO, Carvalho AF, Creed F et al Anxiety and depressive symptoms and illness perceptions in psoriatic arthritis and associations with physical health‐related quality of life. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012; 64: 1593–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boehncke WH, Menter A. Burden of disease: psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2013; 14: 377–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brodszky V, Péntek M, Bálint PV, Géher P, Hajdu O, Hodinka L et al Comparison of the Psoriatic Arthritis Quality of Life (PsAQoL) questionnaire, the functional status (HAQ) and utility (EQ‐5D) measures in psoriatic arthritis: results from a cross‐sectional survey. Scand J Rheumatol 2010; 39: 303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zachariae H. Prevalence of joint disease in patients with psoriasis: implications for therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003; 4: 441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chandran V, Cook RJ, Edwin J, Shen H, Pellett FJ, Shanmugarajah S et al Soluble biomarkers differentiate patients with psoriatic arthritis from those with psoriasis without arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010; 49: 1399–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haroon M, Kirby B, Fitzgerald O. High prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with severe psoriasis with suboptimal performance of screening questionnaires. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72: 736–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eder L, Chandran V, Pellet F, Shanmugarajah S, Rosen CF, Bull SB et al Human leucocyte antigen risk alleles for psoriatic arthritis among patients with psoriasis. Ann Rheum Dis 2012; 71: 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Winchester R, Minevich G, Steshenko V, Kirby B, Kane D, Greenberg DA et al HLA associations reveal genetic heterogeneity in psoriatic arthritis and in the psoriasis phenotype. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64: 1134–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wittkowski KM, Leonardi C, Gottlieb A, Menter A, Krueger GG, Tebbey PW et al Clinical symptoms of skin, nails, and joints manifest independently in patients with concomitant psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. PLoS One 2011; 6: e20279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, McEvoy MT, Gabriel SE, Kremers HM. Incidence and clinical predictors of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a population‐based study. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61: 233–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Langenbruch A, Radtke MA, Krensel M, Jacobi A, Reich K, Augustin M. Nail involvement as a predictor of concomitant psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2014; 171: 1123–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Husni ME, Meyer KH, Cohen DS, Mody E, Qureshi AA. The PASE questionnaire: pilot‐testing a psoriatic arthritis screening and evaluation tool. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57: 581–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gladman DD, Schentag CT, Tom BD, Chandran V, Brockbank J, Rosen C et al Development and initial validation of a screening questionnaire for psoriatic arthritis: the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen (ToPAS). Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68: 497–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ibrahim GH, Buch MH, Lawson C, Waxman R, Helliwell PS. Evaluation of an existing screening tool for psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis and the development of a new instrument: the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009; 27: 469–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tinazzi I, Adami S, Zanolin EM, Caimmi C, Confente S, Girolomoni G et al The early psoriatic arthritis screening questionnaire: a simple and fast method for the identification of arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Rheumatology 2012; 51: 2058–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Coates LC, Aslam T, Al BF, Burden AD, Burden‐Teh E, Caperon AR et al Comparison of three screening tools to detect psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis (CONTEST study). Br J Dermatol 2013; 168: 802–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Buskila D, Langevitz P, Gladman DD, Urowitz S, Smythe HA. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis are more tender than those with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 1992; 19: 1115–1119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haroon M, Gallagher P, FitzGerald O. Diagnostic delay of more than 6 months contributes to poor radiographic and functional outcome in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74: 1045–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boehncke WH, Anliker MD, Conrad C, Dudler J, Hasler F, Hasler P et al The dermatologists' role in managing psoriatic arthritis: results of a Swiss Delphi exercise intended to improve collaboration with rheumatologists. Dermatology 2015; 230: 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. NICE . Clinical guideline 153. Psoriasis. The assessment and management of psoriasis. 2012.

- 25. Christophers E, Barker JN, Griffiths CE, Dauden E, Milligan G, Molta C et al The risk of psoriatic arthritis remains constant following initial diagnosis of psoriasis among patients seen in European dermatology clinics. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24: 548–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eder L, Chandran V, Shen H, Cook RJ, Shanmugarajah S, Rosen CF et al Incidence of arthritis in a prospective cohort of psoriasis patients. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011; 63: 619–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Eder L, Haddad A, Shen H, Rosen C, Cook RJ, Gladman DD. The incidence and risk factors for psa in patients with psoriasis – a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2014; 66(Suppl 1): 1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Luelmo J, Gratacos J, Moreno Martinez‐Losa M, Ribera M, Romani J, Calvet J et al A report of 4 years of experience of a multidisciplinary unit of psoriasis and psoriactic arthritis. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2014; 10: 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Phillips LA, Leventhal H, Leventhal EA. Physicians' communication of the common‐sense self‐regulation model results in greater reported adherence than physicians' use of interpersonal skills. Br J Health Psychol 2012; 17: 244–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Armstrong AW, Robertson AD, Wu J, Schupp C, Lebwohl MG. Undertreatment, treatment trends, and treatment dissatisfaction among patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the United States: findings from the National Psoriasis Foundation surveys, 2003–2011. JAMA Dermatol 2013; 149: 1180–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lloyd P, Ryan C, Menter A. Psoriatic arthritis: an update. Arthritis 2012; 2012: 176298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kavanaugh A. Psoriatic arthritis: treat‐to‐target. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2012; 30(Suppl 73): S123–S125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Breedveld FC, Boumpas D, Burmester G et al Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2010; 69: 631–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smolen JS, Braun J, Dougados M, Emery P, Fitzgerald O, Helliwell P et al Treating spondyloarthritis, including ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis, to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 6–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Coates LC, Moverley A, McParland L, Brown S, Collier H, Brown SR et al Effect of tight control of inflammation in early psoriatic arthritis (TICOPA): a multicentre, open‐label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014; 383: S36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Freire M, Rodriguez J, Moller I, Valcarcel A, Tornero C, Diaz G et al [Prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with psoriatic arthritis attending rheumatology clinics]. Reumatol Clin 2011; 7: 20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Katon W, Ciechanowski P. Impact of major depression on chronic medical illness. J Psychosom Res 2002; 53: 859–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther 2001; 23: 1296–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee S, Mendelsohn A, Sarnes E. The burden of psoriatic arthritis: a literature review from a global health systems perspective. P T 2010; 35: 680–689. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kvamme MK, Lie E, Kvien TK, Kristiansen IS. Two‐year direct and indirect costs for patients with inflammatory rheumatic joint diseases: data from real‐life follow‐up of patients in the NOR‐DMARD registry. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012; 51: 1618–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ritchlin CT, Kavanaugh A, Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Helliwell P, Boehncke WH et al Treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68: 1387–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gossec L, Smolen JS, Gaujoux‐Viala C, Ash Z, Marzo‐Ortega H, van der Heijde D et al European league against rheumatism recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies. Ann Rheum Dis 2012; 71: 4–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kripalani S, Yao X, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance medication adherence in chronic medical conditions: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167: 540–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Radtke MA, Reich K, Blome C, Rustenbach S, Augustin M. Prevalence and clinical features of psoriatic arthritis and joint complaints in 2009 patients with psoriasis: results of a German national survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009; 23: 683–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Theander E, Husmark T, Alenius GM, Larsson PT, Teleman A, Geijer M et al Early psoriatic arthritis: short symptom duration, male gender and preserved physical functioning at presentation predict favourable outcome at 5‐year follow‐up. Results from the Swedish Early Psoriatic Arthritis Register (SwePsA). Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kirkham BW, Li W, Boggs R, Nab H, Tarallo M. Early treatment of psoriatic arthritis is associated with improved outcomes: findings from the etanercept (Enbrel) PRESTA trial. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2015; 33: 11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gladman DD, Sampalis JS, Illouz O, Guerette B. Responses to adalimumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis who have not adequately responded to prior therapy: effectiveness and safety results from an open‐label study. J Rheumatol 2010; 37: 1898–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brussels Declaration . EULAR. 2010.

- 49. Salaffi F, Carotti M, Gasparini S, Intorcia M, Grassi W. The health‐related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis: a comparison with a selected sample of healthy people. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009; 7: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Armstrong EJ, Harskamp CT, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis and major adverse cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational studies. J Am Heart Assoc 2013; 2: e000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhu TY, Li EK, Tam LS. Cardiovascular risk in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Int J Rheumatol 2012; 2012: 714321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Husted JA, Tom BD, Schentag CT, Farewell VT, Gladman DD. Occurrence and correlates of fatigue in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68: 1553–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mau W, Listing J, Huscher D, Zeidler H, Zink A. Employment across chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases and comparison with the general population. J Rheumatol 2005; 32: 721–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Torre Alonso JC, Santos‐Rey J, Ruiz‐Martin JM, Diego P‐D, Moreno M, Fernandez J‐A. Development and validation of a new instrument to asess health related quality of life in psoriasis arthritis: the vitacora questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64(Suppl 10): 531. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fortune DG, Richards HL, Kirby B, Bowcock S, Main CJ, Griffiths CEM. A cognitive‐behavioural symptom management programme as an adjunct in psoriasis therapy. Br J Dermatol 2002; 146: 458–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Halford J, Brown T. Cognitive‐behavioural therapy as an adjunctive treatment in chronic physical illness. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2009; 15: 306–317. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bundy C, Pinder B, Bucci S, Reeves D, Griffiths CEM, Tarrier N. A novel, web‐based, psychological intervention for people with psoriasis: the electronic Targeted Intervention for Psoriasis (eTIPs) study. Br J Dermatol 2013; 169: 329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Augustin M, Alvaro‐Gracia JM, Bagot M, Hillmann O, van de Kerkhof PCM, Kobelt G et al A framework for improving the quality of care for people with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012; 26: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Richard MA, Barnetche T, Rouzaud M, Sevrain M, Villani AP, Aractingi S et al Evidence‐based recommendations on the role of dermatologists in the diagnosis and management of psoriatic arthritis: systematic review and expert opinion. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28: 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Helliwell P, Coates L, Chandran V, Gladman D, de Wit M, FitzGerald O et al Qualifying unmet needs and improving standards of care in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014; 66: 1759–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pham T, Fautrel B, Dernis E, Goupille P, Guillemin F, Le Loët X et al Recommendations of the French Society for Rheumatology regarding TNFalpha antagonist therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitis or psoriatic arthritis: 2007 update. Joint Bone Spine 2007; 74: 638–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Salvarani C, Pipitone N, Marchesoni A, Cantini F, Cauli A, Lubrano E et al Recommendations for the use of biologic therapy in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: update from the Italian Society for Rheumatology. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011; 29(Suppl 66): S28–S41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Machado P, Bogas M, Ribeiro A, Costa J, Neto A, Sepriano A et al 2011 Portuguese recommendations for the use of biological therapies in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Acta Reumatol Port 2012; 37: 26–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fernandez Sueiro JL, Juanola RX, Canete Crespillo JD, Torre Alonso JC, Garcia DV, Queiro SR et al [Consensus statement of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology on the management of biologic therapies in psoriatic arthritis]. Reumatol Clin 2011; 7: 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Coates LC, Tillet W, Chandler D, Helliwell P, Korendowych E, Kyle S et al The 2012 BSR and BHPR guidelines for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis with biologics. Rheumatology 2013; 52: 1754–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]