Abstract

Background

Each individual psoriasis patient has different expectations and goals for biological treatment, which may differ from those of the clinician. As such, a patient‐centred approach to treatment goals remains an unmet need in psoriasis.

Objective

The aim of this study was to review available data on patients’ and physicians’ decision criteria and expectations of biological treatment for moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis with the aim of developing a core set of questions for clinicians to ask patients routinely to understand what is important to them and thus better align physicians’ and patients’ expectations of treatment with biologics and its outcomes.

Methods

A literature search was conducted to identify key themes and data gaps. Aspects of treatment relevant when choosing a biological agent for an individual patient were identified and compared to an existing validated instrument. A series of questions aimed at helping the physician to identify the particular aspects of treatment that are recognised as important to individual psoriasis patients was developed.

Results

Key findings of the literature search were grouped under themes of adherence, decision‐making, quality of life, patient/physician goals, communication, patient‐reported outcomes, satisfaction and patient benefit index. Several aspects of treatment were identified as being relevant when choosing a biological agent for an individual patient.

The questionnaire is devised in two parts. The first part asks questions about patients’ experience of psoriasis and satisfaction with previous treatments. The second part aims to identify the treatment attributes patients consider to be important and may as such affect their preference for a particular biological treatment. The questionnaire results will allow the physician to understand the key factors that can be influenced by biological drug choice that are of importance to the patient. This information can be used be the physician in clinical decision making.

Conclusion

The questionnaire has been developed to provide a new tool to better understand and align patients’ and physicians’ preferences and goals for biological treatment of psoriasis.

Introduction

Biological therapies such as TNF inhibitors are used to treat patients with moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis. They have been shown to improve both disease control and patient satisfaction rates in clinical dermatology practice.1, 2, 3 The ability of biologics to clear, or almost clear, cutaneous disease has changed the outcomes and expectations of many patients with psoriasis.4 Moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis has a negative impact on patient's quality of life and the chronic nature of the disease means that it is important to get treatment right.4, 5 Patient‐reported satisfaction is highest for biologics compared with topical or systemic treatments, with patients rating treatment effectiveness as the most important factor, followed by treatment safety and doctor–patient communication.6

Physicians’ treatment goals based on the psoriasis area severity index (PASI) may not correlate well with measures of patient satisfaction. The recent MAPP study revealed that 22% of patients with a BSA of ≤3 palms rated their disease as severe.5 In one study, more than half of patients who achieved PASI‐50 and 15% of those with PASI‐75 were not satisfied with the condition of their skin; conversely, a third of patients who did not attain PASI‐50 reported a high level of treatment satisfaction.7 Patients tend to focus on subjective concerns such as the softness and suppleness of their skin or alleviation of itch, whereas dermatologists focus on objective measures such as clearance of lesions.8 Anecdotally, clearance of scales, or clearance of psoriasis from visible parts of the body alone, may be sufficient.

The patient benefit index (PBI) is a validated instrument for assessing patient‐relevant benefit in skin diseases. It comprises 25 items grouped into five subscales: (i) reducing social impairment; (ii) reducing psychological impairment; (iii) reducing impairment due to therapy; (iv) reducing physical impairment and (v) having confidence in healing. The validity, feasibility and reliability of the PBI in patients with psoriasis have been tested using data from a cross‐sectional study and a longitudinal study; it was developed in collaboration with patient groups and was shown to be a suitable instrument for the assessment of patient‐reported benefit in the treatment of psoriasis.9

A working group was set up based on the concept that each individual patient has different goals for biological treatment. These treatment goals may differ from those of the clinician. While PASI and patient‐reported outcomes (PROs) are related, they are based on different concepts. As such, a patient‐centred approach to treatment goals remains an unmet need in psoriasis. The working hypothesis for the project reported here was: ‘Understanding the needs and expectations of patients from treatment should constitute a fundamental part of treatment with biologics. At this point this goal has not been fully realised. New tools are needed to incorporate these aspects within therapeutic goals’.

The aim of the working group was to develop a core set of questions for clinicians to ask patients routinely to understand what is important to them and thus better align physicians’ and patients’ expectations and goals of treatment and its outcomes. A literature search was conducted to review existing literature on expectations and goals of both patients and physicians and the decision criteria or existing tools used by physicians to decide on the choice of biological treatment for moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis. Key themes and data gaps were identified and based on this information a series of questions was devised by the working group to aid the practising dermatologist identify aspects of treatment that are recognised as being important to the individual psoriasis patient.

Materials and methods

Literature search

A literature search was designed to answer the following questions:

What are the important decision criteria for clinicians when choosing a biological for the treatment of moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis?

What are patient's expectations from biological treatment?

Do patients’ expectations from treatment differ from those of the physician?

How can we balance these expectations?

What measures can be taken to accommodate life events?

How can dermatology consultation styles be adapted to better align with individual psoriasis patients preferences?

How can we increase patient involvement in disease management and improve interactions with dermatologists?

Which patient‐reported outcome questionnaires align best with patients’ expectations?

A search of PubMed was conducted to find articles published in English between January 1980 and December 2013. Box 1 shows the search terms used. The search was restricted to adult psoriasis patients. Screening was performed by an initial assessor and refined subsequently by an additional assessor. Relevance to the topic was determined by scanning the title and, where available, the abstract of the retrieved articles. To be deemed relevant, articles were required to be related to at least one of the key questions. Related citations to relevant topics were also searched and were required to meet the same criteria for inclusion.

Box 1. Terms used in literature search.

| Primary search terms | |

| Psoriasis + | |

| Biologics + | |

| Secondary search terms | |

| Adherence | Patient global assessment (PtGA) |

| Attitude | Patient goals |

| Beliefs | Patient‐reported outcomes |

| Communication | PBI |

| Decisions | Perception |

| Dermatology life questionnaire index (DLQI) | Physician global assessment (PGA) |

| EQ‐5D | Physician goals |

| Expectation | Preference |

| Experience | Pregnancy |

| Health assessment questionnaire‐disability index (HAQ‐DI) | Quality of life |

| Health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) | Questionnaire |

| Infection | Satisfaction |

| Intervention | SF‐36 |

| Life events | Surgery |

| Patient expectations | Trust |

| Vaccination | |

| Visual analogue scale (VAS) | |

Search completed 30.10.2013.

Questionnaire development

Using their expertise and the findings from the literature search, the core group identified key aspects of treatment relevant to clinicians when making decisions regarding the choice of biological agent for an individual patient. These aspects were checked for consistency with aspects that had previously been identified as important to patients; the validated PBI items.9 The core group then devised a series of questions to help physicians to better identify and understand the aspects of treatment important to psoriasis patients and to support informed decision making on treatment choice. Inviting a patient organisation for comment was an important step in the project plan. Currently, no pan‐European patient organisation is in place. The Italian Association of Psoriatic Patients (ADIPSO), Rome, Italy was invited to review the questionnaire in December 2014. The president of ADIPSO was also the patient representative in the European S3 Psoriasis Guidelines.10 Following comments from this organisation, the questionnaire underwent revision.

A Likert scale, which assumes that all items are considered parallel instruments, was selected as the most suitable way through which patients should specify their level of agreement or disagreement with each statement, thereby expressing the intensity of their feelings for a given item and determining their preference. Scores from each question are given equal importance to allow patients to specify their individual perspectives on the importance of each factor. Linking summative responses from the scale to individual biologics should support treatment decisions according to the suitability of each different biological to meet a patient's preferences.

Results

The literature search returned a total of 398 articles, of which 61 were deemed relevant based on the pre‐specified criteria. A further 22 relevant associated articles were found. Excluding duplications, a total of 52 relevant articles were identified.1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55

Table 1 summarises the agreed key findings of the literature search, grouped under themes of adherence,11, 12 decision‐making,13, 14, 15, 16, 17 quality of life,18, 19, 20, 21, 22 patient/physician goals,23, 24, 25 questionnaire,26 patient‐reported outcomes,3 satisfaction,6, 27 and PBI.9, 28 A number of search terms returned no relevant articles (for example, attitude, belief, infection, life events, patient expectations, perception, pregnancy, vaccination), suggesting gaps in the data in these areas.

Table 1.

Key literature search findings, grouped by theme

| Theme | Key findings |

|---|---|

| Adherence | Different biologics have different levels of adherence9 |

| Better adherence is observed when the dermatologist clarifies the treatment schedule10 | |

| Better adherence is observed when the dermatologist keeps the patient informed and meets the patient's requests10 | |

| Decision making | No biological can be considered best for all patients11 |

| Patient preference should be a major deciding factor in biological choice11 | |

| The dermatologist is the most important source for patient understanding of biologics, followed by research on the internet12 | |

| The life course of patients has an impact on treatment strategies13, 14 | |

| Fear of adverse effects is an important factor in patient preference11, 15 | |

| Quality of life | Treatment strategy has an impact on DLQI16 |

| Patients on topical and traditional systemic therapies have higher DLQI scores16, 17 | |

| Patients with high DLQI and PASI scores benefit most from biologics18 | |

| Skindex‐29, a QoL scoring system, does not correlate with improvements in PASI19 | |

| DLQI is an independent predictor of work productivity20 | |

| Patient/physician goals | Achieving PASI‐75 leads to improvement of the HRQoL index (lack of direct correlation of PASI with DLQI)21, 22 |

| The Patient Benefit Index can be used as goal attainment scaling tool23 | |

| Questionnaires | When addressing the patient, the physician should use simple language and improve the patient′s psychological skills24 |

| It is important to communicate to the patient:24 | |

| (i) That the physician understands the disease | |

| (ii) That there is hope of cure | |

| (iii) The perception of control | |

| Patient‐reported outcomes | A clear definition of patient‐reported outcomes is needed |

| Biologics also have a benefit on non‐PASI outcomes3 | |

| Satisfaction | Patients with high disease severity need a patient‐centred approach, as they are often dissatisfied with therapy25 |

| A study of 1293 patients revealed that topical therapy was significantly associated with least satisfaction; highest satisfaction was seen with biologics5 | |

| For satisfaction, patients rated treatment effectiveness as most important, followed by treatment safety and doctor/patient communication5 | |

| Patient benefit index | PBI is a suitable instrument for the assessment of the patient‐reported benefit8 |

| More tools for understanding parameters of patient benefit and satisfaction are needed26 |

DLQI, dermatology quality of life index; HRQoL, health‐related quality of life; PASI, psoriasis area severity index.

Based on the literature search and their expertise, the core group identified the following attributes as being relevant when choosing a biological agent for an individual patient:

The above list was compared with the validated PBI and through this process, condensed into 9 key questions (Table 2). In this process, each item of the PBI could be assigned to at least two proposed biological treatment‐related attributes, as defined in Box 2, this suggested that the physician's questions – the responses to which will ultimately inform the treatment option chosen – closely align to aspects of treatment of recognised importance to the patient. The assignment also showed that the specific attributes of ‘likelihood of response’ (3) and ‘overall efficacy’ (4) are related to each of the 23 items of the PBI. Conversely, the PBI aspects, ‘ability to lead a normal life’, ‘burden in partnership’, ‘frequency of doctor visits’, ‘out of pocket treatment expenses’ and ‘confidence in the therapy’ were related to greater numbers of biologics attributes and therefore seem to be particularly relevant in differentiating between biologics.

Table 2.

Correlation of PBI with biological treatment‐relevant attributes, as defined in Box 2

| Corresponding items | |

|---|---|

| To be free of pain | 3, 4 |

| To be free of itching | 3, 4 |

| To no longer have burning sensations on your skin | 3, 4 |

| To be healed of all skin defects | 3, 4 |

| To be able to sleep better | 3, 4 |

| To feel less depressed | 3, 4 |

| To experience a greater enjoyment of life | 3, 4 |

| To have no fear that the disease will become worse | 3, 4, 6 |

| To be able to lead a normal everyday life | 3, 4, 1, 7, 8, 2, 11, 12 |

| To be more productive in everyday life | 3, 4, 1 |

| To be less of a burden to relatives and friends | 3, 4 |

| To be able to engage in normal leisure activities | 3, 4 |

| To be able to lead a normal working life | 3, 4, 7, 8, 9 |

| To be able to have more contact with other people | 3, 4 |

| To be comfortable showing yourself more in public | 3, 4 |

| To be less burdened in my partnership | 3, 4, 7, 8, 12 |

| To be able to have a normal sex life | 3, 4 |

| To be less dependent on doctor and clinical visits | 3, 4, 1, 2, 7, 8, 9 |

| To need less time for daily treatment | 3, 4 |

| To have fewer out‐of‐pocket treatment expenses | 3, 4, 7, 8 |

| To have fewer side‐effects | 3, 4, 13 |

| To find a clear diagnosis and therapy | 3, 4 |

| To have confidence in the therapy | 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 13 |

Items within the PBI were correlated with the biological treatment‐relevant attributes (numbered 1–13; Box 2) defined based on expert consensus.

Box 2. Proposed biological treatment attributes.

| 1. Mode of injection |

| 2. Injection frequency (short, intermediate, or long interval between injections) |

| 3. Likelihood of response |

| 4. Overall efficacy |

| 5. Rapidity of response/Onset of action |

| 6. Duration of response |

| 7. Physician monitoring frequency (frequent, moderate frequency, or infrequent) |

| 8. Frequency of hospital/clinic visits (self‐application vs. hospital‐based treatment) |

| 9. Laboratory monitoring |

| 10. Ability to discontinue treatment rapidly (e.g., during major surgery or severe infection)/Flexibility |

| 11. Ability to discontinue treatment on disease remission |

| 12. Low risk for difficulties with respect to pregnancy |

| 13. Safety |

Following receipt of feedback from ADIPSO, the group reviewed and analysed the comments received. The patient organisation agreed that tailored medicine or the individualisation of treatment for psoriasis is of fundamental importance. The changes recommended and subsequently made included offering patients an opportunity to specify their reasons for rating aspects of the questionnaire in a certain manner, and providing patients with options to select from when asking for main symptoms of their disease or treatment history. These changes support the clarification of views or patient preferences that previously may have been unclear to the physician.

The questionnaire is designed for dermatologists to use while with psoriasis patients for whom biological treatment is recommended. Use during consultation will highlight to the patient the physician's awareness of their individual needs.

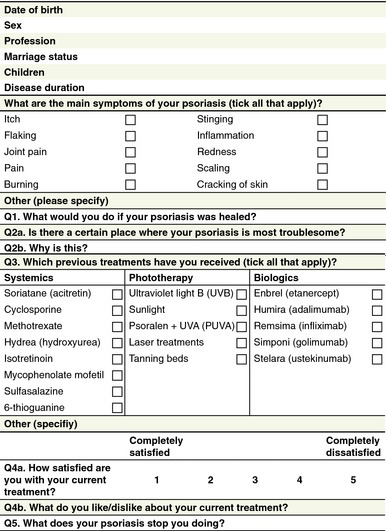

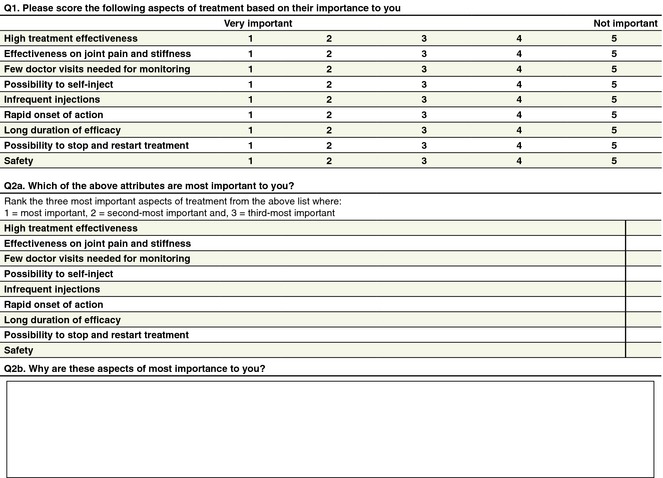

According to purpose and proposed usage, the questionnaire devised by the working group was split in two parts. The first part aims to establish a patient profile (Fig. 1) and determine the patient's experience of psoriasis, as well as patient expectations and satisfaction with previous treatments. The second section aims to identify aspects of biological treatment that are important to the individual patient and the relative importance of these aspects (Fig. 2). Patients are asked to score psoriasis biological treatment‐related considerations from 1 (very important) to 5 (not important). Following this, patients provide more information on their preferences and values with regards to treatment by ranking the three most important treatment aspects from their perspective. Clinical experience may then be used to assign these three most important aspects to different biologics. If several biologics would be covered by these aspects, the other less important aspects may then provide additional help to refine the treatment choice/decision further to best suit the patient's preference and needs.

Figure 1.

Part 1 of the patient‐centred questionnaire.

Figure 2.

Part 2 of the patient‐centred questionnaire.

The questionnaire results will allow the physician to understand the key factors that are of importance to the patient with regards biological treatment. The final question, which asks patients to rank the top three most important factors, allows for a more in depth understanding of the patient's priorities with respect to experience with and outcomes from biological treatment.

Discussion

The new questionnaire described has been developed to provide a tool to better understand and align patients’ needs and goals for biological treatment of psoriasis with the goals of their physicians.

Surveys have found that psoriasis is often perceived by patients as being incomprehensible, incurable and uncontrollable; dermatologists need to convey to patients that the disease can generally be controlled, and provide hope that effective therapies are available.26 Good patient–physician communication is of great importance in ensuring acceptance of, adherence to and satisfaction with therapy.41 In one Italian study, treatment adherence was significantly associated with the degree of patient satisfaction with his/her relationship with the dermatologist.12

A Spanish group has published consensus criteria for the selection of biological therapy in moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis in which they conclude that choice of biological agent could not be based solely on clinical trial response rates and should consider patient‐related factors such as co‐morbidities, disease activity and stability and patient preferences.47 Psoriasis treatment guidelines also recognise the importance of tailoring treatment to the needs of the individual patient.56

The concept of patient‐centred care, with its emphasis on effective two‐way communication, is particularly important in long‐term conditions such as psoriasis that require patient involvement for optimal management.36 Patient preference will depend on a range of factors including age and gender; matching patient preferences for care with the treatment provided is considered to be one of the key attributes of patient‐centred care.52, 53 Positive treatment outcomes such as increased patient satisfaction and health‐related quality of life have been demonstrated when patients’ preferences were incorporated into decision making about treatment.57, 58 In turn, satisfaction with treatment may increase patient adherence, which is important for achieving optimal treatment outcomes.52 Shared decision making, involving negotiation of a treatment regimen that accommodates patients’ goals and preferences, has also been shown to improve adherence and clinical outcomes in other chronic diseases such as asthma.59

This new questionnaire – issued to the patient during consultation with their dermatologist – provides a forum for the patient to clearly and quickly convey their preferences for care. Importantly, its use will also ensure that the physician considers these factors and their importance to the patient when making treatment decisions. Consultation duration in Europe ranges from 10 to 15min60, 61 and it is hoped that this questionnaire will support improved and efficient patient–physician communication while taking into consideration the time challenges of clinical practice.

A full validation process by psoriasis patient organisations to review the final questionnaire and testing under clinical conditions should be undertaken as a second step. While this questionnaire focusses predominantly on the dermatological manifestations of psoriatic disease, a future questionnaire could be developed to include psoriatic arthritis, taking into consideration the potential impact that multidisciplinary care may have on patient–physician communication.

It is hoped that this psoriasis questionnaire will help physicians to take a more structured approach when choosing a biological therapy that incorporates patients’ treatment preferences. The way patients answer the questions will depend on their beliefs, and their views may change after discussion with the dermatologist. The value of this questionnaire is in helping the dermatologist to understand existing patient preferences so that patient‐centred care can be provided. Future steps could include linking summated scores to recommended biologics for individual patients; however, in doing so, care would need to be taken to avoid introducing physicians’ bias and losing the important focus on a patient‐centred approach.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr Mara Maccarone, President of ADIPSO, for her invaluable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of interest

Prim. Professor Robert Strohal serves on speaker bureaus for Pfizer, Schülke and Mayer, Lohmann and Rauscher, Meda Pharmaceuticals, Menarini Pharmaceuticals, Stockhausen, and Smith and Nephew. He has consulting agreements with Pfizer, Astellas, Novartis, Lohmann and Rauscher, Urgo, Chemomedica, Schülke and Mayer and Pantec Biotechnologies. He receives research and educational grants from Pfizer, Stockhausen, 3M‐Woundcare, Smith and Nephew, Lohmann and Rauscher, Enjo Commercials, Urgo, Chemomedica, and Schülke and Mayer. Professor Prinz has served as a consultant, investigator, speaker or advisory board member for Biogen‐Idec (formerly Biogen), Novartis, Wyeth, Pfizer, Merck‐Serono (formerly Serono), Essex Pharma, MSD, Galderma, Centocor, Abbott, Janssen‐Cilag/Janssen‐Ortho. Furthermore he has received an unrestricted research grant from Biogen‐Idec and Wyeth in the past. Professor Giampiero Girolomoni has received honoraria for lectures, manuscript preparation or board membership from Abbvie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Dompè, Galderma, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Hospira, Leo Pharma, Merck‐Serono, Mundipharma, Otsuka, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Rottapharm and Shiseido. PD Dr. Alexander Nast, has received honoraria for CME speaker activities that received indirect funding from Abbott (now Abbvie) and direct funding from Bayer Health Care, Biogen‐Idec (formerly Biogen) and Pfizer.

Funding sources

This manuscript was developed by an unrestricted grant from Pfizer Inc. Medical writing support was provided by Synergy Medical.

References

- 1. Christophers E, Segaert S, Milligan G, Molta CT, Boggs R. Clinical improvement and satisfaction with biologic therapy in patients with severe plaque psoriasis: results of a European cross‐sectional observational study. J Dermatolog Treat 2013; 24: 193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Finlay AY, Ortonne J‐P. Patient satisfaction with psoriasis therapies: an update and introduction to biologic therapy. J Cutan Med Surg 2004; 8: 310–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baker EL, Coleman CI, Reinhart KM et al Effect of biologic agents on non‐PASI outcomes in moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: systematic review and meta‐analyses. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2012; 2: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Laws PM, Young HS. Update of the management of chronic psoriasis: new approaches and emerging treatment options. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2010; 3: 25–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J et al Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population‐based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 70: 871–881. e1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Cranenburgh OD, de Korte J, Sprangers MA, de Rie MA, Smets EM. Satisfaction with treatment among patients with psoriasis: a web‐based survey study. Br J Dermatol 2013; 169: 398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schäfer I, Hacker J, Rustenbach SJ, Radtke M, Franzke N, Augustin N. Concordance of the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) and patient‐reported outcomes in psoriasis treatment. Eur J Dermatol 2010; 20: 62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ersser SJ, Surridge H, Wiles A. What criteria do patients use when judging the effectiveness of psoriasis management? J Eval Clin Pract 2002; 8: 367–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feuerhahn J, Blome C, Radtke M, Augustin M. Validation of the patient benefit index for the assessment of patient‐relevant benefit in the treatment of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res 2012; 304: 433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pathirana D, Ormerod AD, Saiag P et al European S3‐guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009; 23(Suppl 2): 1–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bhosle MJ, Feldman SR, Camacho FT, Timothy Whitmire J, Nahata MC, Balkrishnan R. Medication adherence and health care costs associated with biologics in Medicaid‐enrolled patients with psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat 2006; 17: 294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Altobelli E, Marziliano C, Fargnoli MC et al Current psoriasis treatments in an Italian population and their association with socio‐demographical and clinical features. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012; 26: 976–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nelson AA, Pearce DJ, Fleischer AB, Balkrishnan R, Feldman SR. New treatments for psoriasis: which biologic is best? J Dermatolog Treat 2006; 17: 96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kamangar F, Isip L, Bhutani T et al How psoriasis patients perceive, obtain, and use biologic agents: Survey from an academic medical center. J Dermatolog Treat 2013; 24: 13–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Herrera E, Alcaide AJ. Intermittent use of etanercept in psoriasis. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2010; 101(Suppl 1): 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mrowietz U, Kragballe K, Nast A, Reich K. Strategies for improving the quality of care in psoriasis with the use of treatment goals – a report on an implementation meeting. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011; 25(Suppl 3): 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gisondi P, Farina S, Giordano MV, Zanoni M, Girolomoni G. Attitude to treatment of patients with psoriasis attending spa center. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2012; 147: 483–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chan SA, Hussain F, Lawson LG, Ormerod AD. Factors affecting adherence to treatment of psoriasis: comparing biologic therapy to other modalities. J Dermatolog Treat 2013; 24: 64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ragnarson TG, Hjortsberg C, Bjarnason A et al Treatment patterns, treatment satisfaction, severity of disease problems, and quality of life in patients with psoriasis in three Nordic countries. Acta Derm Venereol 2013; 93: 442–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Norlin JM, Steen Carlsson K, Persson U, Schmitt‐Egenolf M. Switch to biological agent in psoriasis significantly improved clinical and patient‐reported outcomes in real‐world practice. Dermatology 2012; 225: 326–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prignano F, Ruffo G, Ricceri F, Pescitelli L, Lotti T. A global approach to psoriatic patients through PASI score and Skindex‐29. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2011; 146: 47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schmitt JM, Ford DE. Work limitations and productivity loss are associated with health‐related quality of life but not with clinical severity in patients with psoriasis. Dermatology 2006; 213: 102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reich K, Griffiths CE. The relationship between quality of life and skin clearance in moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis: lessons learnt from clinical trials with infliximab. Arch Dermatol Res 2008; 300: 537–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Revicki DA, Willian MK, Menter A, Saurat JH, Harnam N, Kaul M. Relationship between clinical response to therapy and health‐related quality of life outcomes in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Dermatology 2008; 216: 260–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Radtke MA, Schäfer I, Blome C, Augustin M. Patient benefit index (PBI) in the treatment of psoriasis – results of the National Care Study Pso Health. Eur J Dermatol 2013; 23: 212–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Linder D, Dall'Olio E, Gisondi P et al Perception of disease and doctor‐patient relationship experienced by patients: a questionnaire study. Am J Clin Dermatol 2009; 10: 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. DiBonaventura M, Wagner S, Waters H, Carter C. Treatment patterns and perceptions of treatment attributes, satisfaction and effectiveness among patients with psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol 2010; 9: 938–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Krenzer S, Radtke M, Schmitt‐Rau K, Augustin M. Characterization of patient‐reported outcomes in moderate to severe psoriasis. Dermatology 2011; 223: 80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ahn CS, Gustafson CJ, Sandoval LF, Davis SA, Feldman SR. Cost effectiveness of biologic therapies for plaque psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2013; 14: 315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Armstrong AW, Robertson AD, Wu J, Schupp C, Lebwohl MG. Undertreatment, treatment trends, and treatment dissatisfaction among patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the United States: findings from the national psoriasis foundation surveys, 2003–2011. JAMA Dermatol 2013; 149: 1180–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Balato N, Megna M, Di Costanzo L, Balato A, Ayala F. Educational and motivational support service: a pilot study for mobile‐phone‐based interventions in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2013; 168: 201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Basra MK, Hussain S. Application of the dermatology life quality index in clinical trials of biologics for psoriasis. Chin J Integr Med 2012; 18: 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bhutani T, Patel T, Koo B, Nguyen T, Hong J, Koo J. A prospective, interventional assessment of psoriasis quality of life using a non skin‐specific validated instrument that allows comparison with other major medical conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013; 69: e79–e88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Boehncke WH. Modern therapy of psoriasis: evidence‐based, patient‐centered, goal‐oriented. Hautarzt 2012; 63: 589–594; quiz 595–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Driessen RJ, Bisschops LA, Adang EM, Evers AW, Van De Kerkhof PC, De Jong EM. The economic impact of high‐need psoriasis in daily clinical practice before and after the introduction of biologics. Br J Dermatol 2010; 162: 1324–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Feldman S, Behnam SM, Behnam SE, Koo JY. Involving the patient: impact of inflammatory skin disease and patient‐focused care. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 53(1 Suppl 1): S78–S85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guibal F, Iversen L, Puig L, Strohal R, Williams P. Identifying the biologic closest to the ideal to treat chronic plaque psoriasis in different clinical scenarios: using a pilot multi‐attribute decision model as a decision‐support aid. Curr Med Res Opin 2009; 25: 2835–2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Katugampola RP, Lewis VJ, Finlay AY. The Dermatology Life Quality Index: assessing the efficacy of biological therapies for psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2007; 156: 945–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kavanaugh A, McInnes IB, Krueger GG et al Patient‐reported outcomes and the association with clinical response in patients with active psoriatic arthritis treated with golimumab: findings through 2 years of a phase III, multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013; 65: 1666–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lesuis N, Befrits R, Nyberg F, van Vollenhoven RF. Gender and the treatment of immune‐mediated chronic inflammatory diseases: rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis: an observational study. BMC Med 2012; 10: 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lora V, Gisondi P, Calza A, Zanoni M, Girolomoni G. Efficacy of a single educative intervention in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. Dermatology 2009; 219: 316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mahler R, Jackson C, Ijacu H. The burden of psoriasis and barriers to satisfactory care: results from a Canadian patient survey. J Cutan Med Surg 2009; 13: 283–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mease PJ, Menter MA. Quality‐of‐life issues in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: outcome measures and therapies from a dermatological perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 54: 685–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nguyen TV, Hong J, Prose NS. Compassionate care: enhancing physician‐patient communication and education in dermatology. Part I: patient‐centered communication. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013; 68: 353. e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Papp KA, Carey W. Psoriasis care: new and emerging pharmacologic trends. J Cutan Med Surg 2010; 14: 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Paul C, Stalder JF, Thaçi D et al Patient satisfaction with injection devices: a randomized controlled study comparing two different etanercept delivery systems in moderate to severe psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012; 26: 448–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Puig L, Bordas X, Carrascosa JM et al Consensus document on the evaluation and treatment of moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis: Spanish psoriasis group of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2009; 100: 277–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Raval K, Lofland JH, Waters H, Piech CT. Disease and treatment burden of psoriasis: examining the impact of biologics. J Drugs Dermatol 2011; 10: 189–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Reich K, Mrowietz U. Treatment goals in psoriasis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2007; 5: 566–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Reich K, Segaert S, Van de Kerkhof P et al Once‐weekly administration of etanercept 50 mg improves patient‐reported outcomes in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. Dermatology 2009; 219: 239–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Reich K, Sinclair R, Roberts G, Griffiths CE, Tabberer M, Barker J. Comparative effects of biological therapies on the severity of skin symptoms and health‐related quality of life in patients with plaque‐type psoriasis: a meta‐analysis. Curr Med Res Opin 2008; 24: 1237–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Umar N, Litaker D, Schaarschmidt M‐L, Peitsch WK, Schmieder A, Terrid DD. Outcomes associated with matching patients’ treatment preferences to physicians’ recommendations: study methodology. BMC Health Serv Res 2012; 12: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Umar N, Schöllgen I, Terris DD. It is not always about gains: utilities and disutilities associated with treatment features in patients with moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis. Patient Prefer Adherence 2012; 6: 187–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vender R, Lynde C, Gilbert M, Ho V, Sapra S, Poulin‐Costello M. Etanercept improves quality of life outcomes and treatment satisfaction in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in clinical practice. J Cutan Med Surg 2012; 16: 407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wade AG, Crawford GM, Pumford N, Koscielny V, Maycock S, McConnachie A. Baseline characteristics and patient reported outcome data of patients prescribed etanercept: web‐based and telephone evaluation. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011; 11: 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. American Academy of Dermatology Work Group , Menter A, Korman NJ et al Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 6. Guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: case‐based presentations and evidence‐based conclusions. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 65: 137–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kiesler DJ, Auerbach SM. Optimal matches of patient preferences for information, decision‐making and interpersonal behavior: evidence, models and interventions. Patient Educ Couns 2006; 61: 319–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lecluse LL, Tutein Nolthenius JL, Bos JD, Spuls PI. Patient preferences and satisfaction with systemic therapies for psoriasis: an area to be explored. Br J Dermatol 2009; 160: 1340–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wilson S, Strub P, Buist S et al Shared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 181: 566–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Baldwin L, Clarke M, Hands L, Knott M, Jones R. The effect of telemedicine on consultation time. J Telemed Telecare 2003; 9(Suppl 1): S71–S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Deveugele M, Derese A, van den Brink‐Muinen A, Bensing J, De Maeseneer J. Consultation length in general practice: cross sectional study in six European countries. BMJ 2002; 325: 472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]