Abstract

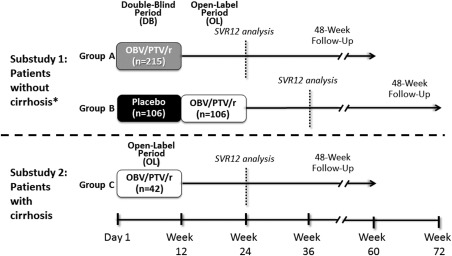

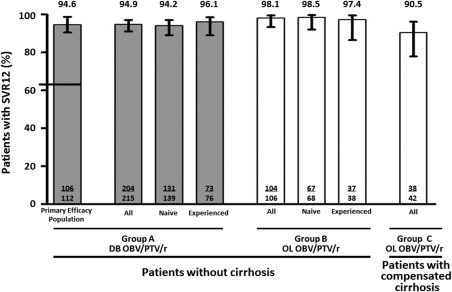

GIFT‐I is a phase 3 trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of a 12‐week regimen of coformulated ombitasvir (OBV)/paritaprevir (PTV)/ritonavir (r) for treatment of Japanese hepatitis C virus genotype 1b–infected patients. It consists of a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled substudy of patients without cirrhosis and an open‐label substudy of patients with compensated cirrhosis. Patients without cirrhosis were randomized 2:1 to once‐daily OBV/PTV/r (25 mg/150 mg/100 mg; group A) or placebo (group B). Patients with cirrhosis received open‐label OBV/PTV/r (group C). The primary efficacy endpoint was the rate of sustained virological response 12 weeks posttreatment in interferon‐eligible, treatment‐naive patients without cirrhosis and hepatitis C virus RNA ≥100,000 IU/mL in group A. A total of 321 patients without cirrhosis were randomized and dosed with double‐blind study drug (106 received double‐blind placebo and later received open‐label OBV/PTV/r), and 42 patients with cirrhosis were enrolled and dosed with open‐label OBV/PTV/r. In the primary efficacy population, the rate of sustained virological response 12 weeks posttreatment was 94.6% (106/112, 95% confidence interval 90.5‐98.8). Sustained virological response 12 weeks posttreatment rates were 94.9% (204/215) in group A, 98.1% (104/106) in group B (open‐label), and 90.5% (38/42) in group C. Overall, virological failure occurred in 3.0% (11/363) of patients who received OBV/PTV/r. The rate of discontinuation due to adverse events was 0%‐2.4% in the three patient groups receiving OBV/PTV/r. The most frequent adverse event in patients in any group was nasopharyngitis. Conclusion: In this broad hepatitis C virus genotype 1b–infected Japanese patient population with or without cirrhosis, treatment with OBV/PTV/r for 12 weeks was highly effective and demonstrated a favorable safety profile. (Hepatology 2015;62:1037‐1046)

Abbreviations

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- CCB

calcium channel blocker

- CI

confidence interval

- DAA

direct‐acting antiviral agent

- GT

genotype

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- IFN

interferon

- LLOQ

lower limit of quantitation

- OBV

ombitasvir

- OTVF

on‐treatment virological failure

- pegIFN

pegylated IFN

- PTV

paritaprevir

- r

ritonavir

- RAV

resistance‐associated variant

- RBV

ribavirin

- SVR

sustained virological response (SVR12, SVR 12 weeks posttreatment)

- TEAE

treatment‐emergent adverse event

- ULN

upper limit of normal

In Japan, it is estimated that 2 million people are infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV).1 Prevalence of HCV infection increases with age in the Japanese population.2 While HCV genotype (GT) 1a infection is common in North America and western Europe, in Japan approximately 99% of HCV GT1‐infected patients have GT1b.3

In HCV GT1‐infected Japanese patients without cirrhosis, 12‐week regimens of simeprevir with pegylated interferon (pegIFN) and ribavirin (RBV) plus 12‐36 additional weeks of pegIFN/RBV increased sustained virological response (SVR) rates compared to pegIFN/RBV alone.4, 5, 6 However, these regimens result in SVR rates of only 36%‐53% in prior nonresponders, emphasizing the need for more efficacious therapies for this population.5 Simeprevir plus pegIFN/RBV therapy is also subject to treatment‐limiting toxicity associated with pegIFN and RBV, including hematological abnormalities resulting from pegIFN‐mediated bone marrow suppression and inhibition of compensatory red blood cell reticulocytosis.7 An IFN/RBV‐free regimen of the direct‐acting antiviral agents (DAAs) daclatasvir and asunaprevir, administered twice daily, has recently been approved in Japan for the treatment of HCV GT1.8, 9 The daclatasvir and asunaprevir regimen eliminates pegIFN‐related toxicity and achieves an SVR rate of 80.5% in previous nonresponders, but it has reduced efficacy to 40.5% in patients with baseline Y93 or L31 variants in NS5A and requires 24 weeks of treatment.10 New IFN/RBV‐free treatment regimens for Japanese patients with durations as low as 12 weeks are emerging.11, 12

A phase 2, randomized, open‐label trial recently reported the efficacy and safety of the DAAs ombitasvir (OBV, an NS5A inhibitor) and paritaprevir (PTV, an NS3/4A protease inhibitor identified by AbbVie and Enanta that is administered with low‐dose ritonavir [r] to increase PTV's peak, trough, and overall drug exposure [PTV/r]) for treatment of HCV GT1b infection in Japanese patients.11 Prior pegIFN/RBV treatment–experienced, HCV GT1b‐infected Japanese patients without cirrhosis received 100/100 mg or 150/100 mg PTV/r plus 25 mg OBV once daily for 12 or 24 weeks. High SVR rates 12 and 24 weeks posttreatment (SVR12 and SVR24, respectively; with a concordance of 100%) and a low rate of discontinuation due to adverse events were observed in HCV GT1b‐infected patients regardless of treatment duration or PTV/r dose.11 A regimen of OBV/PTV/r plus the NS5B polymerase inhibitor dasabuvir is approved for treatment of HCV GT1b‐infected patients in the United States and Europe. The two‐DAA regimen of OBV/PTV/r is being explored in Japanese patients due to the high prevalence of HCV GT1b and GT2 in Japan combined with the broad antiviral activity of OBV and PTV, dasabuvir's lack of activity against GT2,13, 14, 15 and the modestly increased PTV exposures observed in Japanese compared to Western patients.16

Here, we report the efficacy and safety results from the phase 3 GIFT‐I study, which examined the IFN‐ and RBV‐free regimen of coformulated OBV/PTV/r in Japanese treatment‐naive and treatment‐experienced HCV GT1b‐infected patients with and without cirrhosis.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

GIFT‐I is a phase 3 trial consisting of two substudies (one double‐blind and placebo‐controlled, one open‐label; Fig. 1) conducted at 54 sites in Japan (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02023099). The study was approved by all institutional review boards and conducted in accordance with the protocol, International Conference on Harmonization guidelines, applicable regulations, and guidelines governing clinical study conduct and the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent before enrolling in the study.

Figure 1.

GIFT‐I study design. *Randomization was 2:1 to groups A and B. Abbreviations: DB, double‐blind; OL, open‐label.

Patient Population

Patients were enrolled from December 2013 through April 2014. Eligible patients were male or female, treatment‐naive or treatment‐experienced (previously treated with an interferon (IFN)–based therapy [IFN‐α, IFN‐β, or pegIFN, with or without RBV]), 18‐75 years old, inclusive, with chronic HCV GT1b infection and HCV RNA level >10,000 IU/mL. Patients were excluded if they were coinfected with HBV or human immunodeficiency virus, were previously treated with a DAA, or had any cause of liver disease other than chronic HCV infection. Substudy 1 enrolled patients with no past or current clinical evidence of cirrhosis. Substudy 2 enrolled patients with compensated cirrhosis (Child‐Pugh score A), no clinical history of liver decompensation, serum alpha‐fetoprotein ≤100 ng/mL, and no evidence of hepatocellular carcinoma on imaging. In each substudy, presence or absence of cirrhosis was based on liver biopsy, FibroScan, FibroTest/aspartate aminotransferase‐to‐platelet ratio index, or discriminant score test. Additional details of the eligibility criteria are in the Supporting Information.

Study Medication

In substudy 1, patients without cirrhosis were randomized 2:1 to receive double‐blind OBV/PTV/r 25 mg/150 mg/100 mg (group A) or double‐blind placebo (group B) once daily for 12 weeks (Fig. 1). Following the double‐blind period, patients in group B received 12 weeks of open‐label OBV/PTV/r 25 mg/150 mg/100 mg once daily. The randomization was stratified according to prior IFN‐based therapy (naive versus experienced). Treatment‐naive patients were further stratified by HCV RNA level (<100,000 IU/mL versus ≥100,000 IU/mL, in accordance with definitions of low and high HCV RNA levels by the Japan Society of Hepatology17). Patients with HCV RNA ≥100,000 IU/mL were further stratified by eligibility for IFN‐based therapy (eligible versus ineligible). Previously IFN‐treated patients were further stratified by type of previous response to IFN‐based therapy (relapse, nonresponder, or intolerant to IFN‐based therapy). The randomization schedule was computer‐generated by the sponsor. Sites used interactive response technology for randomization of patients to treatment.

The investigators, patients, and the sponsor were unaware of the treatment assignment during the double‐blind period. To prevent implicit unblinding, investigators, patients, and the sponsor were also blinded to levels of HCV RNA, IFN‐γ‐induced protein 10, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin (indirect and total), and gamma‐glutamyltransferase. In substudy 2, patients with compensated cirrhosis were enrolled into group C and received open‐label OBV/PTV/r 25 mg/150 mg/100 mg once daily for 12 weeks.

Efficacy

Plasma HCV RNA levels were determined using the COBAS TaqMan real‐time reverse‐transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay, version 2.0 (Roche, Nutley, NJ; lower limit of quantitation [LLOQ], 25 IU/mL; lower limit of detection, 15 IU/mL). The primary efficacy endpoint was SVR12 (HCV RNA < LLOQ 12 weeks after end of treatment) in the primary efficacy population (treatment‐naive patients without cirrhosis in group A who were eligible for IFN‐based therapy and had HCV RNA ≥100,000 IU/mL). Secondary efficacy endpoints were on‐treatment virological failure (OTVF), relapse, and SVR12 rate in subpopulations: (1) treatment‐naive patients without cirrhosis and HCV RNA <100,000 IU/mL; (2) treatment‐naive, IFN‐ineligible patients without cirrhosis; (3) treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis with relapse after a prior IFN‐based therapy; (4) treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis who were prior nonresponders to IFN‐based therapy; (5) treatment‐experienced, IFN‐intolerant patients without cirrhosis; and (6) patients with compensated cirrhosis. Additional analyses included normalization of ALT in patients without cirrhosis.

The primary analysis reported in this article was conducted after all patients in groups A and C reached posttreatment week 12 or prematurely discontinued the study. The primary analysis included efficacy data for groups A and C and safety data from the double‐blind treatment period for groups A and B and the open‐label period for group C. Additional analyses evaluated efficacy and safety data from open‐label treatment for group B after all patients in this group reached posttreatment week 12 or prematurely discontinued the study. The final data for the primary efficacy analysis were collected in October 2014, and the final data for SVR12 analysis in group B were collected in January 2015.

On‐treatment virological failure was defined as confirmed HCV RNA ≥ LLOQ at any point during treatment after HCV RNA < LLOQ, confirmed increase of >1 log10 IU/mL from nadir in HCV RNA at any point during treatment, or failure to achieve HCV RNA < LLOQ with at least 6 weeks of treatment. Relapse was defined as HCV RNA < LLOQ at the end of treatment with a confirmed HCV RNA ≥ LLOQ between the final treatment visit and 12 weeks after the last dose of study drug, among patients with at least one posttreatment HCV RNA value who completed treatment (study drug duration ≥77 days). ALT normalization was defined as a final ALT level less than or equal to the upper limit of normal (ULN) in the double‐blind treatment period for patients with ALT > ULN at baseline.

Safety

Adverse events were evaluated at all study visits. Data on all adverse events were collected from the start of study drug administration through 30 days after the last dose of study drug. Serious adverse events were recorded from the time a patient signed the informed consent form through the end of study participation. Adverse events were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 17.0, and their severity was graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0. Clinical laboratory testing was performed at visits during the treatment and posttreatment periods.

Resistance Analyses

Resistance testing was performed on all available patient samples at baseline and for patients who did not achieve SVR on the first available sample after virological failure (OTVF or relapse) who had an HCV RNA level ≥1000 IU/mL. Resistance‐associated variants (RAVs) in NS3/4A (D168E) and NS5A (L28M, R30Q, L31F/M/V, Q54Y, P58S, A92E, Y93H/S) were identified by population sequencing.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic, efficacy, and safety analyses were performed on the intent‐to‐treat population, defined as all patients who received at least one dose of double‐blind or open‐label study drug. Data from substudies 1 and 2 were analyzed separately. The primary efficacy analysis compared the SVR12 rate in the primary efficacy population to a predefined threshold of 63%, based on the historical SVR rate of 73% in the corresponding population of Japanese patients treated with telaprevir plus pegIFN/RBV.18 Due to the expected safety and tolerability benefits of the IFN‐free OBV/PTV/r regimen in Japanese patients,11 a threshold 10% lower than the historical SVR rate was considered acceptable. To establish superiority, the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the SVR12 rate in the primary efficacy population, calculated using the normal approximation to the binomial distribution, was to exceed 63%.

Based on the considerations for the primary efficacy end point, it was calculated that a sample size of 100 treatment‐naive Japanese patients without cirrhosis who were eligible for IFN‐based therapy and had HCV RNA ≥100,000 IU/mL in the active drug group (group A) would provide >90% power to demonstrate superiority to the predefined threshold of 63%, assuming an expected SVR12 rate of 95% with the study drug. Additional details of planned sample sizes of subpopulations of interest are provided in Supporting Table S1. No formal comparisons to an SVR threshold were performed within these subpopulation groups.

Secondary efficacy endpoints were analyzed in patients in groups A and C who received active study drug. Percentages with SVR12, OTVF, and relapse were also assessed in patients in group B who received active study drug during the open‐label period. Except for the primary analysis of the primary efficacy endpoint, two‐sided 95% CIs for the SVR12 rates were calculated using the Wilson score method.

Rates of ALT normalization, treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs), and postbaseline grade 3 or 4 laboratory abnormalities during the double‐blind treatment period were compared between patients in groups A and B with a Fisher's exact test. Safety data for group B and group C during the open‐label treatment period were summarized separately. SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), for the UNIX operating system, was used for all analyses. All statistical tests and CIs were two‐sided with a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Baseline Patient Demographics and Characteristics

Of 467 patients screened, 321 patients without cirrhosis were randomized in substudy 1 (215 to double‐blind OBV/PTV/r [group A], 106 to double‐blind placebo [group B]) and 42 patients with cirrhosis were enrolled in substudy 2 (open‐label OBV/PTV/r [group C]) (Fig. 1; Supporting Fig. S1). All enrolled patients received at least one dose of study drug. The baseline characteristics of patients without cirrhosis in groups A and B (substudy 1) were generally similar (Table 1). Among patients with cirrhosis (substudy 2), 78.6% were treatment‐experienced, and mean (standard deviation) baseline platelet count, albumin, and international normalized ratio were 114.2 (47.4) x 109 cells/L, 38.2 (3.9) g/L, and 1.060 (0.091), respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Patient Characteristics

| Substudy 1 Patients Without Cirrhosis | Substudy 2 Patients With Cirrhosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A DB OBV/PTV/r (n = 215) | Group B DB Placebo (n = 106) | Group C OL OBV/PTV/r (n = 42) | |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 135 (62.8) | 59 (55.7) | 22 (52.4) |

| Age, years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 61.1 (9.6) | 61.5 (9.3) | 61.8 (8.3) |

| ≥ 65, n (%) | 86 (40.0) | 47 (44.3) | 21 (50.0) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 22.4 (3.1) | 22.3 (2.7) | 23.6 (3.6) |

| ≥25, n (%) | 45 (20.9)a | 14 (13.2) | 13 (31.0) |

| IL28B CC genotype, n (%) | 120 (55.8) | 54 (50.9) | 27 (64.3) |

| HCV RNA level | |||

| Log10 IU/mL, mean (SD) | 6.74 (0.58) | 6.68 (0.61) | 6.64 (0.71) |

| ≥100,000 IU/mL, n (%) | 211 (98.1) | 103 (97.2) | 41 (97.6) |

| Prior therapy (IFN status) | |||

| Treatment‐naive, n (%) | 139 (64.7) | 68 (64.2) | 9 (21.4) |

| IFN‐eligible, n/N (%) | 116/139 (83.5) | 58/68 (85.3) | NA |

| IFN‐ineligible, n/N (%) | 23/139 (16.5) | 10/68 (14.7) | NA |

| Treatment‐experienced,b n (%) | 76 (35.3) | 38 (35.8) | 33 (78.6) |

| Relapser, n/N (%) | 22/76 (28.9) | 11/38 (28.9) | 8/33 (24.2) |

| Nonresponder, n/N (%) | 28/76 (36.8) | 14/38 (36.8) | 19/33 (57.6) |

| IFN‐intolerant, n/N (%) | 26/76 (34.2) | 13/38 (34.2) | 5/33 (15.2) |

| Baseline fibrosis stage | |||

| F0‐F1, n/N (%) | 49/82 (59.8) | 23/31 (74.2) | 0 |

| F2, n/N (%) | 17/82 (20.7) | 1/31 (3.2) | 0 |

| F3, n/N (%) | 16/82 (19.5) | 7/31 (22.6) | 1 (2.4)c |

| F4, n/N (%) | 0 | 0 | 41 (97.6) |

| Missing datad, n | 133 | 75 | 0 |

Statistically significant difference between group A and group B (placebo) using chi‐squared test at P = 0.05 level.

One treatment‐experienced patient with cirrhosis had a missing response type.

Discriminant score at screening indicated presence of cirrhosis, but FibroTest at baseline indicated stage F3.

Values were missing for a total of 208 patients whose cirrhosis status (yes/no) was determined by serum discriminant score, which does not differentiate between Metavir scores F0 to F3.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DB, double‐blind; NA, not available; OL, open‐label; SD, standard deviation.

Virological Response

Rapid virological and end‐of‐treatment responses and SVR4 for the three patient groups are presented in Supporting Table S2. SVR12 rates for patients with and without cirrhosis receiving OBV/PTV/r are displayed in Fig. 2. In the primary efficacy population, the SVR12 rate was 94.6% (106/112, 95% CI 90.5‐98.8). The lower bound of the 95% CI was 90.5%, establishing superiority of the OBV/PTV/r regimen to the predefined threshold (Fig. 2). The overall SVR12 rate among patients without cirrhosis in group A was 94.9% (204/215); the SVR12 rates in all treatment‐naive and treatment‐experienced patients were 94.2% (131/139) and 96.1% (73/76), respectively.

Figure 2.

SVR12 rates. Error bars represent 95% CIs calculated by normal approximation to the binomial for the primary efficacy population and by Wilson score method for all others. The threshold of 63% (based on the historical telaprevir‐based SVR rate) to which the SVR12 rate for the primary efficacy population was compared is marked with a horizontal line in the first column. The primary efficacy population was composed of patients randomized to group A who received study drug and who were treatment‐naive without cirrhosis, were IFN‐eligible, and had HCV RNA ≥100,000 IU/mL. Abbreviations: DB, double‐blind; OL, open‐label.

The overall SVR12 rate in patients without cirrhosis receiving open‐label OBV/PTV/r (group B) was 98.1% (104/106); SVR12 rates in treatment‐naive and treatment‐experienced patients were 98.5% (67/68) and 97.4% (37/38), respectively, in this group. The overall SVR12 rate in patients with cirrhosis receiving open‐label OBV/PTV/r (group C) was 90.5% (38/42), including 100% (9/9) and 87.9% (29/33) in treatment‐naive and treatment‐experienced patients, respectively. SVR12 rates for all other predefined subpopulations were >90% (Table 2).

Table 2.

SVR12 Rates in Subpopulations of Patients Without Cirrhosis

| Group A DB OBV/PTV/r (n = 215) | Group B OL OBV/PTV/r (n = 106) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | % (95% CI) | n/N | % (95% CI) | |

| All patients without cirrhosis | 204/215 | 94.9 (91.1‐97.1) | 104/106 | 98.1 (93.4‐99.5) |

| Treatment‐naive | 131/139 | 94.2 (89.1‐97.1) | 67/68 | 98.5 (92.1‐99.7) |

| HCV RNA <100,000 IU/mL | 6/6 | 100 (61.0‐100) | 2/2 | 100 (34.2‐100) |

| IFN‐ineligible | 21/23 | 91.3 (73.2‐97.6) | 9/10 | 90.0 (59.6‐98.2) |

| Treatment‐experienced | 73/76 | 96.1 (89.0‐98.6) | 37/38 | 97.4 (86.5‐99.5) |

| Relapser | 21/22 | 95.5 (78.2‐99.2) | 10/11 | 90.9 (62.3‐98.4) |

| Nonresponder | 28/28 | 100 (87.9‐100) | 14/14 | 100 (78.5‐100) |

| IFN‐intolerant | 24/26 | 92.3 (75.9‐97.9) | 13/13 | 100 (77.2‐100) |

HCV RNA <100,000 IU/mL and IFN‐ineligible were not mutually exclusive. The 95% CIs were calculated using the Wilson score method.

Abbreviations: DB, double‐blind; OL, open‐label.

ALT Normalization

In patients without cirrhosis with ALT levels greater than ULN at baseline, ALT normalized at the end of the double‐blind treatment period in a significantly greater proportion in patients receiving OBV/PTV/r versus placebo (94.3% [116/123] versus 18.9% [10/53]; P < 0.001).

Virological Failure

Virological failure (OTVF or relapse) occurred in 3.0% (11/363) of patients who received OBV/PTV/r (double‐blind and open‐label periods). Virological failure occurred in 2.8% (6/215), 1.9% (2/106), and 7.1% (3/42) of patients in groups A, B, and C, respectively. OTVF occurred in 0.5% (1/215), 0.9% (1/106), and 2.4% (1/42) of patients in groups A, B, and C, respectively. Relapse occurred in 2.4% (5/209), 1.0% (1/105), and 5.0% (2/40) of patients in groups A, B, and C, respectively. Additional information on patients who experienced virological failure is in Supporting Table S3.

Resistance‐Associated Variants

RAVs in NS3/4 and NS5A were detected in 1% and 38% of patients at baseline, respectively. The most commonly detected NS3A and NS5A RAVs in baseline samples were D168E (4/351, 1%) and Y93H (49/357, 14%), respectively. RAVs were observed in both NS3 and NS5A at the time of virological failure in 10 of the 11 patients who experienced OTVF or relapse. In NS3, D168V alone or in combination with Y56H was observed in 73% (8/11) of patients, D168A in combination with Y56H was observed in two patients, and one patient did not have any treatment‐emergent RAVs in NS3. In NS5A, Y93H was preexisting in eight patients and at the time of failure; Y93H alone or in combination with L28M, R30Q, L31M, L31V, and/or P58S was observed in 91% (10/11) of patients; L31F was observed in one patient.

Safety

Rates of TEAEs in the three patient groups are in Table 3. During the double‐blind period, a greater percentage of patients without cirrhosis receiving OBV/PTV/r than placebo experienced TEAEs (68.8% [148 of 215 patients] versus 56.6% [60 of 106 patients], P < 0.05) (Table 3). TEAEs were predominantly grade 1 or 2 in severity. TEAEs occurring with a frequency >5% among patients without cirrhosis during the double‐blind period in either treatment group were nasopharyngitis (16.7% [36 patients], OBV/PTV/r; 13.2% [14 patients], placebo), headache (8.8% [19 patients], OBV/PTV/r; 9.4% [10 patients], placebo), and peripheral edema (5.1% [11 patients], OBV/PTV/r; 0%, placebo). The only TEAE significantly more frequent with OBT/PTV/r versus placebo during the double‐blind period was peripheral edema. The proportions of serious TEAEs and TEAEs leading to study drug discontinuation were not significantly different in patients receiving OBV/PTV/r versus placebo (3.3% [seven patients] versus 1.9% [two patients], P > 0.05; and 0.9% [two patients] versus 0%, P > 0.05, respectively). TEAEs leading to study drug discontinuation in patients receiving OBV/PTV/r were anuria and hypotension in one patient each.

Table 3.

Overview of TEAEs and Laboratory Value Abnormalities in Patients With and Without Cirrhosis

| Substudy 1 Patients Without Cirrhosis | Substudy 2 Patients With Cirrhosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A DB OBV/PTV/r (n = 215) | Group B DB Placebo (n = 106) | Group B OL OBV/PTV/r (n = 106) | Group C OL OBV/PTV/r (n = 42) | |

| Any TEAE, n (%) | 148 (68.8)a | 60 (56.6) | 68 (64.2) | 31 (73.8) |

| TEAE leading to discontinuation, n (%) | 2 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.4) |

| Serious TEAE,b n (%) | 7 (3.3) | 2 (1.9) | 3 (2.8) | 2 (4.8) |

| Common TEAEs,c n (%) | ||||

| Nasopharyngitis | 36 (16.7) | 14 (13.2) | 8 (7.5) | 6 (14.3) |

| Headache | 19 (8.8) | 10 (9.4) | 7 (6.6) | 3 (7.1) |

| Peripheral edema | 11 (5.1)a | 0 | 4 (3.8) | 3 (7.1) |

| Nausea | 9 (4.2) | 4 (3.8) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (7.1) |

| Pyrexia | 4 (1.9) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) | 4 (9.5) |

| Decreased platelet count | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (7.1) |

| Postbaseline abnormalities in laboratory values (grade 3 or higher), n/N (%) | ||||

| ALT, >5× ULN | 1/213 (0.5) | 1/106 (0.9) | 0 | 0 |

| AST, >5× ULN | 0 | 1/106 (0.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Total bilirubin, >3× ULN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/42 (2.4) |

| Hemoglobin, <8 g/dL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The only statistical comparisons of safety data performed were between groups A and B during the double‐blind period.

P < 0.05 Fisher's exact test (A versus B during the double‐blind period).

Definition in Supporting Information.

Occurring in >5% of patients in any group.

Abbreviations: AST, aspartate aminotransferase; DB, double‐blind; OL, open‐label.

The TEAE profile in patients without cirrhosis receiving open‐label OBV/PTV/r was comparable to that of patients without cirrhosis receiving double‐blind OBV/PTV/r (Table 3). TEAEs were predominantly grade 1 or 2. TEAEs occurring with a frequency >5% in this group were nasopharyngitis (7.5% [eight patients]) and headache (6.6% [seven patients]). Peripheral edema occurred in 3.8% (four patients) of patients. Serious TEAEs occurred in 2.8% (three patients) of patients in this group, and no patient discontinued treatment due to TEAEs.

Among patients with cirrhosis receiving open‐label OBV/PTV/r, 73.8% (31 of 42 patients) experienced at least one TEAE (Table 3). TEAEs were predominantly grade 1 or 2 in severity. TEAEs occurring with a frequency >5% were nasopharyngitis (14.3% [six patients]), pyrexia (9.5% [four patients]), nausea (7.1% [three patients]), peripheral edema (7.1% [three patients]), decreased platelet count (7.1% [three patients]), and headache (7.1% [three patients]). Serious TEAEs occurred in 4.8% (two patients) of patients with cirrhosis. One patient (2.4%) had a serious TEAE (pulmonary edema) that led to study drug discontinuation.

All patients in the study who experienced a TEAE of peripheral edema were using concomitant calcium channel blockers (CCBs). Additional analyses indicated that the incidence of any edema‐related TEAEs (defined as peripheral edema, edema, face edema, or pulmonary edema) was related to the use and dose of CCBs (Supporting Tables S4 and S5).

There were no deaths due to a TEAE in any patient group; however, two deaths occurred more than 30 days after the end of treatment. One patient was a 71‐year‐old female with compensated cirrhosis who experienced a fatal nonrelated, non‐TEAE of lymphangiosis carcinomatosa on posttreatment day 76. HCV RNA levels were less than the LLOQ at all measurements from open‐label treatment day 11 until posttreatment day 54, the last time point measured. The other patient was a 65‐year‐old female with compensated cirrhosis who achieved SVR12 and experienced a nonrelated, non‐TEAE of hepatocellular carcinoma on posttreatment day 84 and died on posttreatment day 253.

Postbaseline laboratory values of grade 3 or higher are presented in Table 3. There were no grade 4 values for any laboratory parameter. One diabetic patient without cirrhosis receiving double‐blind OBV/PTV/r had an asymptomatic ALT value greater than five times the ULN, concurrent with acute worsening of glycemia during betamethasone use. ALT peaked at treatment day 57 (556 IU/mL) and resolved while continuing DAA treatment. In this patient, discontinuation of betamethasone was followed by decrease of blood glucose levels and ALT declines. This patient completed study drug and achieved SVR12. Another patient without cirrhosis receiving double‐blind placebo had elevations in ALT and aspartate aminotransferase greater than five times the ULN. There were no grade 3 or higher elevations in total bilirubin in patients without cirrhosis. One patient with cirrhosis receiving open‐label OBV/PTV/r had a total bilirubin elevation greater than three times the ULN. This patient was diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma on posttreatment day 84 and died on posttreatment day 253. No patient met biochemical criteria for Hy's law.

There were no hemoglobin decreases <8 g/dL. No patient received erythropoietin or blood transfusions during the study. No patient had a decrease in platelet count below 50 × 109/L.

Discussion

The results from this phase 3 trial in Japanese patients with HCV GT1b infection with or without cirrhosis demonstrated that high SVR rates can be achieved with 12 weeks of the IFN‐free and RBV‐free regimen of OBV/PTV/r. These high SVR12 rates are comparable with or higher than those reported for other two‐DAA and three‐DAA IFN‐free regimens that have been evaluated in Japan, Europe, and the United States.10, 12, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28

A 24‐week regimen of daclatasvir once daily and asunaprevir twice daily achieved SVR24 rates of 84.0% (168/200) and 90.9% (20/22) in Japanese HCV GT1b‐infected patients without and with cirrhosis, respectively.10 A recent report on 12‐week regimens of ledipasvir and sofosbuvir with or without RBV indicated SVR12 rates of 100% (171/171) for the RBV‐free and 98% (167/170) for the RBV‐containing regimen in Japanese patients.12 In the current study, high SVR12 rates were demonstrated in a broad HCV GT1b‐infected Japanese patient population receiving a 12‐week regimen of once‐daily OBV/PTV/r. The rates of discontinuation due to adverse events were comparably low for OBV/PTV/r and other regimens.10, 12

A low rate of virological failure (3%, 11/363) was observed in this study; RAVs were observed in both NS3 and NS5A in 10 of 11 patients who experienced virological failure, including eight patients who had preexisting NS5A RAV Y93H. In Japan, it has been reported that the NS5A variant Y93H is present in 8.2%‐25% of Japanese HCV GT1b‐infected patients.29 The NS5A variant Y93H in GT1b decreased activity of the NS5A inhibitor daclastavir in Japanese patients.10 In an analysis of patients who received ledipasvir and sofosbuvir in phase 3 trials in the United States and Europe, 37 patients (29 GT1a, 8 GT1b) experienced virological failure.30 Among the eight GT1b virological failures, 88% (7/8) had virus with NS5A variant L31I/M/V or Y93H in samples at the time of virological failure. Three of these seven (43%) HCV GT1b‐infected patients were reported to have had baseline NS5A RAVs. Interestingly, the patient who experienced relapse in the study evaluating the efficacy of ledipasvir and sofosbuvir in Japanese patients had HCV GT1b with NS5A variant Y93H at baseline and at the time of relapse.12 Unfortunately, the study did not provide the frequency of specific NS5A RAVs detected at baseline; thus, no assessment can be made about the impact of preexisting NS5A RAVs to ledipasvir in Japanese patients. However, the data from the United States and Europe studies suggest a potential impact of NS5A RAVs on the activity of ledipasvir. In our study the frequency of preexisting Y93H was 14%, and 83% of patients harboring that NS5A RAV achieved SVR12.

In the current trial, 90.5% (38/42) of patients with cirrhosis achieved SVR12. Notably, the 7.1% rate of virological failure observed in patients with cirrhosis in the current study results from only three patients experiencing virological failure. It is unknown whether extending treatment duration or coadministration of RBV would result in increased efficacy in this population or in populations such as patients with baseline RAVs.

The double‐blind, placebo‐controlled design of substudy 1 allowed a robust analysis of safety in this trial through a direct comparison between patients without cirrhosis receiving OBV/PTV/r and those receiving placebo. TEAEs experienced by patients receiving either OBV/PTV/r or placebo during the double‐blind period were predominantly grade 1 or 2 in severity. There was no significant difference between groups in the rate of serious TEAEs or TEAEs leading to discontinuation. Among TEAEs occurring in >5% of patients, only peripheral edema occurred significantly more frequently in patients receiving OBV/PTV/r versus placebo. All patients in this study who experienced peripheral edema were also taking concurrent CCBs. Peripheral edema is known to be associated with CCBs.31 Concomitant administration of OBV/PTV/r with CCBs may result in increased plasma levels of CCBs due to a known drug–drug interaction with ritonavir.32 Post hoc analyses indicated that the frequency of edema‐related adverse events in this study was related to the dose of CCBs, with patients on the lowest dose of CCBs experiencing a numerically lower frequency of edema‐related events. These data suggest that either lowering the dose of CCBs or substituting with a drug of a different class should be considered during OBV/PTV/r treatment.

An elevation in ALT to greater than five times the ULN occurred in a patient in this study who was receiving concomitant betamethasone. A pharmacodynamic interaction has been observed between ethinyl estradiol and the OBV/PTV/r plus dasabuvir regimen,33 suggesting that this elevation may have been related to steroid use. However, the pattern of increase and resolution of ALT levels in this patient were unlike those previously observed in patients receiving concomitant ethinyl estradiol; therefore, the ALT elevation in this patient was not believed to be related to betamethasone use. Furthermore, reports suggest a relationship between elevated glucose levels and elevated ALT,34, 35 and this ALT elevation occurred in a diabetic patient concurrent with acute worsening of glycemia.

This trial included a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled substudy, which facilitated a robust comparison of adverse events in patients receiving active regimen versus placebo. However, in groups that received open‐label treatment, the open‐label design may have impacted reporting of adverse events. Additional limitations are the small number of patients included in some subpopulations and the exclusion of patients who previously received HCV therapy that included a DAA.

In conclusion, high SVR12 rates were achieved with the IFN‐ and RBV‐free OBV/PTV/r regimen in HCV GT1b‐infected Japanese patients. This two‐DAA regimen was well tolerated with low rates of discontinuation due to TEAEs. Together these results suggest that the OBV/PTV/r regimen is a promising therapeutic option for HCV GT1b‐infected patients in Japan.

Author names in bold designate shared co‐first authorship.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.27972/suppinfo.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgment

We thank the trial participants, investigators, and coordinators who made this study possible as well as Kenji Nonaka, Travis Yanke, Takuma Matsuda, Xinyan Zhang, Prajakta Badri, Rajeev M. Menon, Radhika M. Rao, Marion P. Dehaan, Shigeki Hashimoto, Christine Collins, Gretja Schnell, Rakesh Tripathi, Preethi Krishnan, Tom Reisch, and Jill Beyer for their contributions. Medical writing support was provided by Christine Ratajczak (AbbVie).

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Kumada has receive payment for lectures from AbbVie GK, MDS KK, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co. Ltd., Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Toray Industries, Inc., and owns a patent with SRL, Inc. Dr. Chayama has consulted for AbbVie Inc., Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Eisai; received research funding from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Toray Industries, Inc., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ajinomoto, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Kowa, Kyorin, MSD, Nippon Kayaku, Nippon Siyaku, Nippon Shinyaku, Roche, Teijin, Torii, Tsumura, Zeria, and Daiichi Sankyo; and received payment for lectures from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, MSD, Ajinomoto, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline KK, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eisai, Janssen, Kyorin, Meiji Seika, Toray Industries, Inc., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Torii, Zeria, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Dr. Ikeda has served on the speakers' bureau for Dainippon‐Sumitomo Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Olympus Co. Ltd., Eisai Co. Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Nippon Kayaku Co. Ltd., and Bayer Co. Ltd. Dr. Karino has received payment for lectures from Bristol‐Myers Squibb. Dr. Matsuzaki has received grants from Mistubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Ajinomoto Pharma, Eisai Pharma, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, AbbVie, Daiichi Sankyo, Toray Industries, Minophagen Pharma, Otsuka Pharma, Kyowa, and Kirin, and has been on the speakers' bureau for Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Ajinomoto Pharma, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Janssen. Dr. Kioka has received payment for lectures from Toray Industries, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., MSD, Ajinomoto, Janssen, Kowa, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb. Dr. Sato received grants from AbbVie, Dainippon Sumitomo, MSD, and Daiichi Sankyo. He has other interests with Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Chugai. Dr. Pilot‐Matias is employed by and owns stock in AbbVie. Dr. Redman is employed by and owns stock in AbbVie. Dr. Setze is employed by and owns stock in AbbVie. Dr. Vilchez is employed by and owns stock in AbbVie. Dr. Burroughs is employed by and owns stock in AbbVie and owns stock in Merck. Dr. Rodrigues is employed by and owns stock in AbbVie and owns stock in Abbott. Dr. Patwardhan is employed by and owns stock in AbbVie. Dr. Suzuki is on the speakers’ bureau for Bristol‐Myers Squibb.

Supported by AbbVie Inc., which contributed to the design and conduct of the study, data management, data analysis, interpretation of data, and the review and approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Chung H, Ueda T, Kudo M. Changing trends in hepatitis C infection over the past 50 years in Japan. Intervirology 2010;53:39‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tanaka J, Kumagai J, Katayama K, Komiya Y, Mizui M, Yamanaka R, et al. Sex‐ and age‐specific carriers of hepatitis B and C viruses in Japan estimated by the prevalence in the 3,485,648 first‐time blood donors during 1995‐2000. Intervirology 2004;47:32‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Takada A, Tsutsumi M, Okanoue T, Matsushima T, Komatsu M, Fujiyama S. Distribution of the different subtypes of hepatitis C virus in Japan and the effects of interferon: a nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1996;11:201‐207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hayashi N, Izumi N, Kumada H, Okanoue T, Tsubouchi H, Yatsuhashi H, et al. Simeprevir with peginterferon/ribavirin for treatment‐naive hepatitis C genotype 1 patients in Japan: CONCERTO‐1, a phase III trial. J Hepatol 2014;61:219‐227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Izumi N, Hayashi N, Kumada H, Okanoue T, Tsubouchi H, Yatsuhashi H, et al. Once‐daily simeprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin for treatment‐experienced HCV genotype 1‐infected patients in Japan: the CONCERTO‐2 and CONCERTO‐3 studies. J Gastroenterol 2014;49:941‐953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumada H, Hayashi N, Izumi N, Okanoue T, Tsubouchi H, Yatsuhashi H, et al. Simeprevir (TMC435) once daily with peginterferon‐alpha‐2b and ribavirin in patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection: the CONCERTO‐4 study. Hepatol Res 2015;45:501‐513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ronzoni L, Aghemo A, Rumi MG, Prati G, Colancecco A, Porretti L, et al. Ribavirin suppresses erythroid differentiation and proliferation in chronic hepatitis C patients. J Viral Hepat 2014;21:416‐423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sunvepra (asunaprevir) capsules prescribing information. Tokyo, Japan: Bristol‐Myers KK; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Daklinza (daclatasvir) tablets prescribing information. Tokyo, Japan: Bristol‐Myers KK; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kumada H, Suzuki Y, Ikeda K, Toyota J, Karino Y, Chayama K, et al. Daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for chronic HCV genotype 1b infection. Hepatology 2014;59:2083‐2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chayama K, Notsumata K, Kurosaki M, Sato K, Rodrigues L Jr, Setze C, et al. Randomized trial of interferon‐ and ribavirin‐free ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir in treatment‐experienced HCV‐infected patients. Hepatology 2015;61:1523‐1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mizokami M, Yokosuka O, Takehara T, Sakamoto N, Korenaga M, Mochizuki H, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir fixed‐dose combination with and without ribavirin for 12 weeks in treatment‐naive and previously treated Japanese patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C: an open‐label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15:645‐653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kati W, Koev G, Irvin M, Beyer J, Liu Y, Krishnan P, et al. In vitro activity and resistance profile of dasabuvir, a nonnucleoside hepatitis C virus polymerase inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015;59:1505‐1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Krishnan P, Beyer J, Mistry N, Koev G, Reisch T, DeGoey D, et al. In vitro and in vivo antiviral activity and resistance profile of ombitasvir, an inhibitor of hepatitis C virus NS5A. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015;59:979‐987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pilot‐Matias T, Tripathi R, Cohen D, Gaultier I, Dekhtyar T, Lu L, et al. In vitro and in vivo antiviral activity and resistance profile of the hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease inhibitor ABT‐450. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015;59:988‐997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Menon R, Kapoor M, Dumas E, Badri P, Campbell A, Gulati P, et al. Multiple‐dose pharmacokinetics and safety following coadministration of ABT‐450/r, ABT‐267 and ABT‐333 in Caucasian, Japanese and Chinese subjects [Abstract]. In: Proceedings of the 23rd Conference of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver; June 6‐9, 2013; Singapore. Abstract 1497.

- 17. Drafting Committee for Hepatitis Management Guidelines, Japan Society of Hepatology . JSH Guidelines for the Management of Hepatitis C Virus Infection: A 2014 Update for Genotype 1. Hepatol Res 2014;(44 Suppl. S1):59‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kumada H, Toyota J, Okanoue T, Chayama K, Tsubouchi H, Hayashi N. Telaprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin for treatment‐naive patients chronically infected with HCV of genotype 1 in Japan. J Hepatol 2012;56:78‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Afdhal N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR, Lawitz E, Gordon SC, Schiff E, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1483‐1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Kwo P, Chojkier M, Gitlin N, Puoti M, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1889‐1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Andreone P, Colombo MG, Enejosa JV, Koksal I, Ferenci P, Maieron A, et al. ABT‐450, ritonavir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir achieves 97% and 100% sustained virologic response with or without ribavirin in treatment‐experienced patients with HCV genotype 1b infection. Gastroenterology 2014;147:359‐365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Everson GT, Sims KD, Rodriguez‐Torres M, Hezode C, Lawitz E, Bourliere M, et al. Efficacy of an interferon‐ and ribavirin‐free regimen of daclatasvir, asunaprevir, and BMS‐791325 in treatment‐naive patients with HCV genotype 1 infection. Gastroenterology 2014;146:420‐429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Feld JJ, Kowdley KV, Coakley E, Sigal S, Nelson DR, Crawford D, et al. Treatment of HCV with ABT‐450/r‐ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1594‐1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ferenci P, Bernstein D, Lalezari J, Cohen D, Luo Y, Cooper C, et al. ABT‐450/r‐ombitasvir and dasabuvir with or without ribavirin for HCV. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1983‐1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lawitz E, Gane E, Pearlman B, Tam E, Ghesquiere W, Guyader D, et al. Efficacy and safety of 12 weeks versus 18 weeks of treatment with grazoprevir (MK‐5172) and elbasvir (MK‐8742) with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection in previously untreated patients with cirrhosis and patients with previous null response with or without cirrhosis (C‐WORTHY): a randomised, open‐label phase 2 trial. Lancet 2015;385:1075‐1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muir A, Poordad F, Lalezari JP, Everson GT, Dore GJ, Kwo P, et al. All‐oral fixed‐dose combination therapy with daclatasvir/asunaprevir/BMS‐791325, ± ribavirin, for patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection and compensated cirrhosis: UNITY‐2 phase 3 SVR12 results. Hepatology 2014;60(6 Suppl.):1267A. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Poordad F, Hezode C, Trinh R, Kowdley KV, Zeuzem S, Agarwal K, et al. ABT‐450/r‐ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin for hepatitis C with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1973‐1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zeuzem S, Jacobson IM, Baykal T, Marinho RT, Poordad F, Bourliere M, et al. Retreatment of HCV with ABT‐450/r‐ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1604‐1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kan T, Hashimoto S, Kawabe N, Murao M, Nakano T, Shimazaki H, et al. The clinical features of patients with a Y93H variant of hepatitis C virus detected by a PCR invader assay. J Gastroenterol 2015; doi:10.1007/s00535‐015‐1080‐1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harvoni (ledipasvir and sofosbuvir) tablets prescribing information. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Amlodin. Osaka, Japan: Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Norvirr (ritonavir) tablets 100 mg. Tokyo, Japan: AbbVie GK; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Menon R, Badri P, Wang T, Polepally A, Zha J, Khatri A, et al. Drug–drug interaction profile of the all‐oral anti‐hepatitis C virus regimen of paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir and dasabuvir. J Hepatol 2015;63:20‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Behrends M, Martinez‐Palli G, Niemann CU, Cohen S, Ramachandran R, Hirose R. Acute hyperglycemia worsens hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:528‐535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Miyake Y, Eguchi H, Shinchi K, Oda T, Sasazuki S, Kono S. Glucose intolerance and serum aminotransferase activities in Japanese men. J Hepatol 2003;38:18‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.27972/suppinfo.

Supplementary Information