Abstract

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a promising research tool for brain imaging and developmental biology. Serving as a three-dimensional optical biopsy technique, OCT provides volumetric reconstruction of brain tissues and embryonic structures with micrometer resolution and video rate imaging speed. Functional OCT enables label-free monitoring of hemodynamic and metabolic changes in the brain in vitro and in vivo in animal models. Due to its non-invasiveness nature, OCT enables longitudinal imaging of developing specimens in vivo without potential damage from surgical operation, tissue fixation and processing, and staining with exogenous contrast agents. In this paper, various OCT applications in brain imaging and developmental biology are reviewed, with a particular focus on imaging heart development. In addition, we report findings on the effects of a circadian gene (Clock) and high-fat-diet on heart development in Drosophila melanogaster. These findings contribute to our understanding of the fundamental mechanisms connecting circadian genes and obesity to heart development and cardiac diseases.

Index Terms: Biological systems, Biomedical optical imaging, Brain, Cardiovascular system and Optical tomography

I. INTRODUCTION

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) [1–3] is one of most rapidly developed optical imaging modalities of the last few decades. OCT imaging is analogous to ultrasound B-mode imaging, measuring echo time delay of backscattered light. Instead of direct measurement of time delay of reflected photons, OCT uses low coherence interferometry to map out back-scattering properties from different depths of samples. OCT is able to provide in situ and in vivo images of tissue morphology with a resolution approaching that of conventional histology, but without the need to excise or process specimens. Currently, OCT has been widely used clinically in ophthalmology [4–10], cardiology [11–15], endoscopy [16–23], dermatology [24–29] and oncology [24–29]. In recent years, there has been a growing need for high-speed, high-resolution optical imaging modalities for neuroimaging and developmental biology. Recent development of high speed and ultrahigh resolution OCT technologies [30–33] makes it possible to reveal fast dynamics and cellular features of the brain and developing embryos. These benefits, combined with label-free and non-invasive imaging capabilities, OCT becomes an attractive research tool for scientists working in these research fields.

OCT has been demonstrated as a promising neuroimaging tool [34–36]. OCT enables non-invasive visualization of structures and functionality of the brain, which is valuable for fundamental research and medical diagnosis. OCT reveals fine structural details of brain tissues with the capability to resolve individual neurons and myelinated fibers [34]. Moreover, signals originated from brain activities, such as cerebral blood flow/velocity, oxygen saturation and neural action potentials can be characterized using functional OCT [36–38]. Both structural and functional information provided by OCT has been utilized to study brain diseases, such as brain tumors [35] and stroke [36].

In developmental biology, OCT has been used to characterize morphological and functional development of organs, such as eyes [39], brain [40], limbs [41], reproductive organs [42] and the heart [11, 40, 43–45]. The embryonic heart especially, undergoes significant morphological and functional changes during development. Traditionally, structural changes of the developing heart were evaluated based on histological slides using standard light microscope. OCT is able to provide micron-scale resolution images of cardiac morphology and functionality in vivo without the need for heart dissection and processing. Moreover, OCT imaging is non-invasive, enabling longitudinal studies of the developing heart. To date, OCT has been used extensively to study heart development in various animal models, including Xenopus [11], zebrafish [40], chicken and quail [43], mouse [44] and Drosophila [45].

In this paper, we provide a comprehensive review of OCT applications for brain imaging and developmental biology. In addition, we include recent results from our group’s ongoing projects. We had previously shown that a circadian clock gene, Cry, plays an essential role in heart morphogenesis and function [45]. Here, we report the effect of another circadian gene, Clock, on Drosophila’s heart development. We observed that changes in the expression of dClock resulted in cardiac dysfunction at various developmental stages of the fly. Moreover, obesity is associated with many diseases, including cardiovascular diseases [46, 47]. Previous studies showed that high-fat-diet (HFD) induces metabolic and transcriptional response in Drosophila [48]. Here we report the effect of HFD on heart development in Drosophila. We found that HFD-induced cardiac dysfunctions include altered heart rate (HR) and cardiac activity period (CAP) at different developmental stages. These findings contribute to our understanding of the fundamental mechanisms connecting circadian genes and obesity to heart development and cardiac diseases.

II. OCT IN BRAIN IMAGING

Various neuroimaging modalities reveal brain structures and functions at different anatomical levels. Computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) are widely used clinical imaging modalities to evaluate brain structures and functions. Functional MRI (fMRI) measures hemodynamic changes associated with local neuronal activity and is widely used to study functional correlations of different brain regions [49–51]. However, limited spatial and temporal resolutions of these imaging modalities prohibit their utility to evaluate fast neural activities at cellular levels. Microelectrode arrays, electroencephalography and magnetoencephalography directly measure electronic signals originated from neural activities [52–57]. However, these methods have low spatial resolution and are susceptible to electrical noises and motion artifacts [58, 59].

Optical imaging, such as confocal microscopy and two-photon microscopy, has been widely used in neuroscience to study neural activities at the cellular level [60–62]. Confocal and two-photon microscopies utilize fluorescence contrast (mostly from exogenous dyes) to measure neuron morphology and distribution [63], ion concentration [64] and synaptic release [65], cerebral blood flow and angiograms [66, 67]. OCT offers a complementary method for neuroimaging. Based solely on intrinsic optical contrast originating in the brain, OCT can distinguish various brain structures, such as corpus callosum and hippocampus [68, 69], and reveal individual neurons and myelinated fibers [34]. Polarization-sensitive OCT (PS-OCT) was utilized to localize nerve fiber bundles, characterize fiber bundle orientations, and obtain optical tractography of the brain [70, 71]. Based on detection of Doppler shift and light scattering changes, OCT can be used to measure cerebral blood flow and obtain angiograms in vivo [36, 72, 73]. Spectroscopic OCT has been recently developed to measure cerebral blood oxygenation in live animals [74]. Combining blood flow and oxygen saturation measurements enables direct measurement of cerebral metabolism rate of oxygen (CMRO2) [37]. Furthermore, OCT has been used to measure small light scattering and phase changes associated with neuron action potentials [38]. Combining structural and functional information with high temporal and spatial resolutions, OCT promises to be a powerful imaging tool for fundamental and clinical research to understand brain functions and disorders.

OCT resolves details of brain morphology

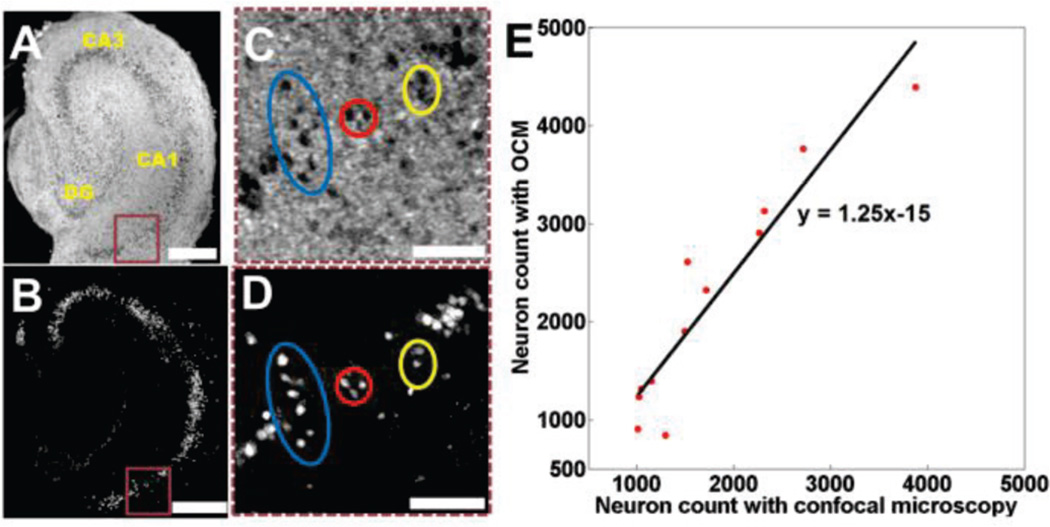

Utilizing broadband light sources and high-magnification objectives, the high resolution extension of OCT, optical coherence microscopy (OCM) [75, 76], can achieve 1–2 µm resolution in tissue in all three dimensions. OCM is able to resolve individual neurons based on intrinsic optical contrast in rodent brains [34, 77, 78] and in human brain slices [79, 80]. Neurons are shown as hyposcattering regions in OCM images (Fig. 1A, C). OCM revealed the same individual neurons observed in confocal microscopy (Fig. 1C, D) [78], two-photon microscopy [34, 77] and histological slides [79, 80]. Neuron count obtained with OCM from 3D organotypic brain cultures also showed linear correlation with confocal microscopy (Fig. 1E) [78].

Fig. 1.

(A) Ultrahigh resolution OCM image of an organotypic hippocampal culture on DIV 7 and corresponding confocal image (B). (C, D) Magnified areas indicated by brown rectangular boxes, highlighting individual neurons observed in both images. (E) A linear correlation (R2 = 0.89) was observed between neuron counts obtained from OCM and confocal images. Scaled bars: 400 µm in (A B), and 100 µm in (C, D). Images reproduced from reference [78 with permission.

OCM can also resolve individual myelinated fibers ex vivo and in vivo [34, 81]. OCM revealed individual myelinated fibers, shown as hyperscattering lines, matched well with Gallayas myelin staining [34]. Combined with optical clearing [82], OCM was used for depth-resolved quantification of myelin contents several millimeters below the cortical surface [34]. Furthermore, impaired myelination, shown as weaker reflected signals from nerve fibers, were observed in peripheral nervous system of Krox20 mutant mice [81].

PS-OCT measures depth-resolved polarization information of tissues, such as phase retardation and optic axis orientations, in order to resolve tissue microstructures with an improved contrast [83–85]. PS-OCT can differentiate white matter from the adjacent gray matter in ex vivo rat cerebral cortex [86]. PS-OCT was sensitive to light polarization changes in nerve fiber bundles and was used to effectively characterize fiber bundle orientations in fixed rat brains [70]. In addition, PS-OCT was also used to obtain optical tractography of ex vivo in rat brains [71]. Details of brain architecture and nerve fiber tracts were clearly resolved with PS-OCT based on tissue birefringence contrast.

Functional OCT imaging of brain activity

Brain activity, cerebral metabolism and cerebrovascular response are closely related [87]. Functional OCT has been used to directly measure vascular, hemodynamic and metabolic changes in animal brains in response to neuronal activities [37, 38].

Doppler OCT [88–91] and OCT angiograms [34, 72, 90, 92–95] measure Doppler shift and temporal fluctuation of light reflected from blood vessels. High-resolution angiograms of surface and deep cortical microvasculature have been demonstrated in rat brains in vivo [36, 72]. Changes in cortical vessel diameter and distribution can be directly measured from OCT angiograms in order to characterize vascular response to neuron activities (e.g. neurovascular coupling [96]). In addition, absolute cerebral blood flow can also be quantified based on Doppler OCT measurements [73].

Spectroscopic OCT measures wavelength-dependent tissue absorption in order to obtain hemoglobin concentration and oxygen saturation information [97–101]. Spectroscopic OCT based on near-infrared light (e.g. ~800 nm center wavelength) [97, 98, 101] was not very sensitive to tissue oxygenation changes due to the relatively low tissue absorption in the near-infrared wavelength range. In the visible wavelength range (~500 nm to 600 nm), the absorption of oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin is more than 40× higher than in the near-infrared wavelength range (~800 nm) [102]. For the same change in hemoglobin concentration or tissue oxygen saturation change, visible light would experience a much larger intensity change than near-infrared light even when propagated through only a few hundred microns of tissue. Recently developed visible light OCT (vis-OCT) successfully mapped oxygen saturation of the mouse brain with high-resolution, enabling accurate assessment of oxygen delivery from microvasculature to surrounding tissues [74]. Combining cerebral blood flow (enabled by Doppler OCT) and oxygenation (enabled by spectroscopic OCT) measurements would allow direct characterization of cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) with micrometer resolutions [37].

OCT has been used in combination with optical intrinsic signal imaging (OISI) and laser speckle imaging (LSI) to characterize hemodynamic changes near cortical surface [103–106]. OISI and LSI map changes of blood oxygenation and blood flow in the cortex with high spatial and temporal resolution. However, they lack the ability to differentiate layered responses of brain activities. OCT provides depth-resolved information about hemodynamic changes in the cortex, such as blood vessel diameter, blood flow, and light scattering, and complements OISI and LSI in order to better characterize neurovascular coupling [104–107].

In addition to characterizing slow cerebral hemodynamic changes, fast signals directly related to neuron activities can be measured using OCT [38, 59, 103, 108–110]. Fast intrinsic scattering changes associated with evoked neural activities in the abdominal ganglion and bag cell neurons of Aplysia californica were measured with high speed OCT [108]. Using ultrahigh resolution OCT, phase changes in the neural cord of American cockroach in response to electrical stimulation was measured [111]. Phase-sensitive OCT also measured depth-resolved optical path length changes during action potential propagations [38, 109]. Phase changes corresponding to a few nanometer membrane displacements were recorded on a time scale of a few milliseconds from a squid giant axon and correlated fairly well with recorded electrical action potentials [110]. With further improvement in imaging speed and phase-sensitivity, OCT holds the potential to reliably detect fast intrinsic optical signals, especially phase changes associated with membrane displacement of individual neurons during action potentials.

OCT imaging of brain pathology

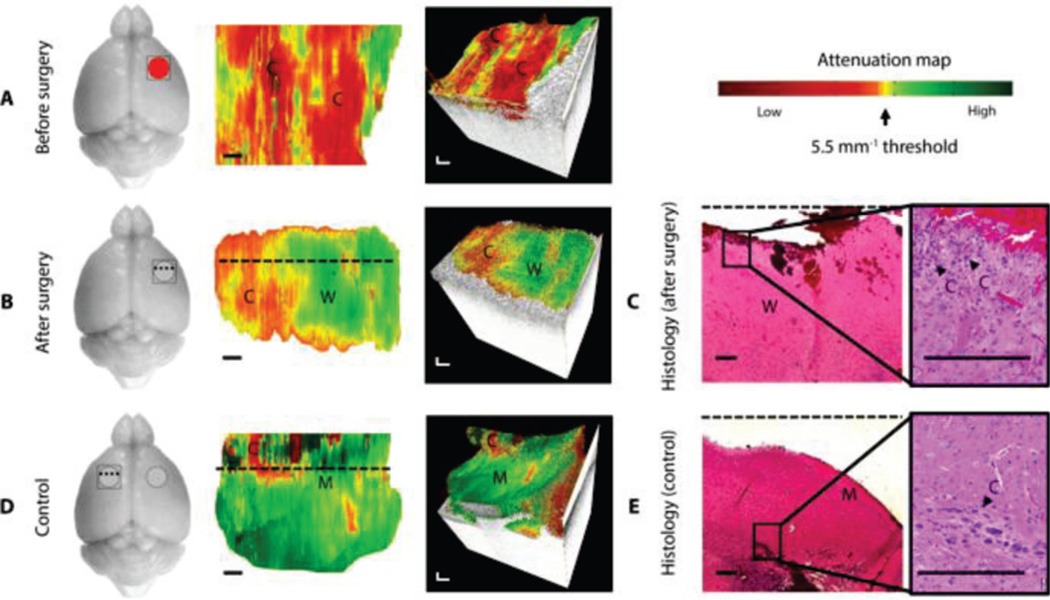

High resolution OCT has been used to image various brain pathologies. Characteristic structural features in brain tumors, such as microcalcifications, enlarged nuclei of tumor cells, small cysts and enhanced vasculatures, can be clearly identified in OCT images [112, 113]. Furthermore, tumorous tissues have distinctive optical attenuation properties compared to normal brain tissues [35, 113, 114]. Recently, OCT has been demonstrated to reliably identify brain tumor margins in vivo and in real-time in a mouse model (Fig. 2) [35]. From optical attenuation maps, cancer regions were clearly identified from noncancer white matter and meninges tissues. Residual tumor cells were identified by OCT and confirmed by histology at post-surgery site and at a seemingly healthy area on the contralateral side of the mouse brain (Fig. 2B–E). These results demonstrated the translational potential of OCT for rapid intraoperative margin assessment of brain cancer.

Fig. 2.

In vivo brain cancer imaging in a mouse with patient-derived highgrade brain cancer (GBM272). Representative images of a mouse brain at the cancer site before surgery (A) and at the resection cavity after surgery (B). (C) Corresponding histology for the resection cavity after surgery. With the same mouse, control images were obtained at a seemingly healthy area on the contralateral, left side of the brain (D), with its corresponding histology (E). Black arrow in histology indicated residual cancer cells corresponding to yellow/red regions on optical attenuation maps. C, cancer; W, noncancer white matter; M, noncancer meninges. Scale bars, 0.2 mm. Images reproduced from reference [35] with permission.

Cerebral amyloid-β (Aβ) amyloidosis, an early and critical biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease, has been visualized ex vivo and in vivo in Alzheimeric mouse models with OCM [115]. Amyloid plaques were detected up to 500 µm below the cortical surface. OCM revealed amyloid plaques corresponded well with immunohistochemical stained images and confocal images. Amyloid plaques were also visualized in longitudinal imaging. Label-free, in vivo OCM imaging would help characterize cerebral amyloid-β amyloidosis, demonstrating its potential to evaluate amyloid-β targeting therapies.

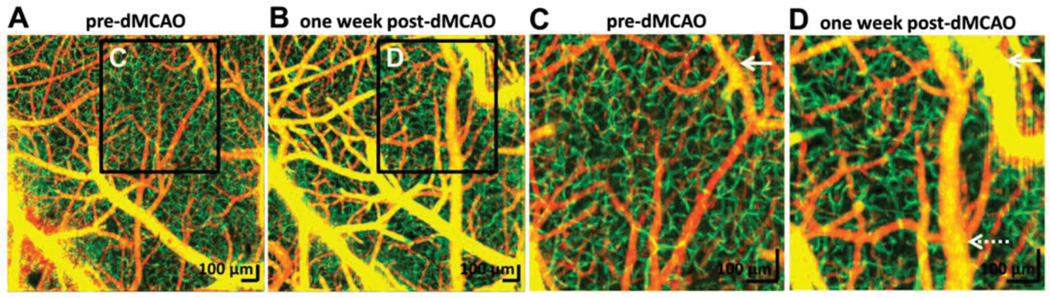

Functional OCT can provide direct measurement of hemodynamic changes caused by stroke in animal models [36, 116, 117]. Both acute and chronic stroke models were investigated in order to gain insights on the injury and brain recovery [36]. For acute stroke, absence of capillary perfusion, reduced regional blood flow, altered light scattering and impaired autoregulation were visualized and quantified with OCT. In chronic stroke models, redistribution of blood flow and vascular remodeling (e.g. pial collateral growth, angiogenesis and dural vessel dilation) were revealed one week after the injury (Fig. 3). These results demonstrated that OCT can be a powerful label-free imaging tool for stroke research, providing 3D high resolution maps of cerebral hemodynamic information in animal models in vivo.

Fig. 3.

OCT angiographs of cerebral areas of mice before (A) and after (B) one week permanent distal middle cerebral artery occlusion (dMCAO). (C, D) Zoomed images indicated significant pial collateral growth (white arrows), dural vessel dilation (dotted arrows). Irregular capillary bed in (D) suggested vascular remodeling and possible angiogenesis. Images reproduced from reference [36] with permission.

Intraoperative OCT, such as catheter-based OCT, has been developed to provide high-resolution imaging guidance during stereotactic neurosurgery in live animals [118, 119]. Compared with conventional pre-operative MRI, OCT offers ~100× higher spatial resolution, revealing cellular level details of the brain in vivo. Real-time imaging information provided by OCT was successfully used to guide microsurgical procedures and delivery of therapeutic agents to specific regions in the deep brain with minimum disturbance of overlying structures [118, 119]. Intraoperative OCT has also been demonstrated to provide structural information of the rat brain in order to guide probe placement for deep brain stimulation [120].

III. OCT IMAGING IN DEVELOPMENT BIOLOGY

In developmental biology, it is desirable to have non-invasive and label-free imaging technologies that are capable of imaging developing specimens. OCT generates micron-scale resolution cross-sectional and 3D images of biological samples and offers a moderate imaging depth of 1–2 mm in tissue. Due to its non-invasiveness nature, OCT has often been used to obtain time-lapsed and longitudinal images of the developing specimens over time. It is suitable for evaluation of morphological and functional development of organs, such as eyes [39], brain [40], limbs [41], reproductive organs [42] and the heart [11, 40, 43–45].

OCT has been used to characterize growth of ocular structures in zebrafish and mouse embryos [39, 40, 121]. Ocular features such as the cornea, iris, lens, vitreous, retina, and retinal pigment epithelium-choriocapillary complex were clearly observed in zebrafish embryos [40]. Quantitative assessment of ocular structures in mouse embryos was demonstrated in utero [121]. Changes of major axis diameters and volumes of embryonic eye lens were characterized at different developmental stages.

Development of brain morphology has been visualized with OCT in small animal models, such as Xenopus [122], zebrafish [40, 123] and fetal mouse [124]. Basic structures of the early embryonic brain, including diencephalic ventricles, midbrain and hindbrain, were revealed within 24 hours post fertilization in zebrafish [40]. Morphology progression of more sophisticated brain structures including the olfactory bulb, telencephalon, cerebellum, medulla, tectum opticum and optic commissure, were visualized in adult zebrafish using OCT [123, 125, 126], showing progression of brain morphology. Optical attenuation in zebrafish brain was quantified, demonstrating a negative linear correlation between optical signal attenuation and brain aging [123].

OCT imaging of limb development has been demonstrated in mouse embryos [41]. In late embryonic stages, indentations between digits and the non-uniform structure of digits were identified. Cartilage primordia were also observed in digits and bones.

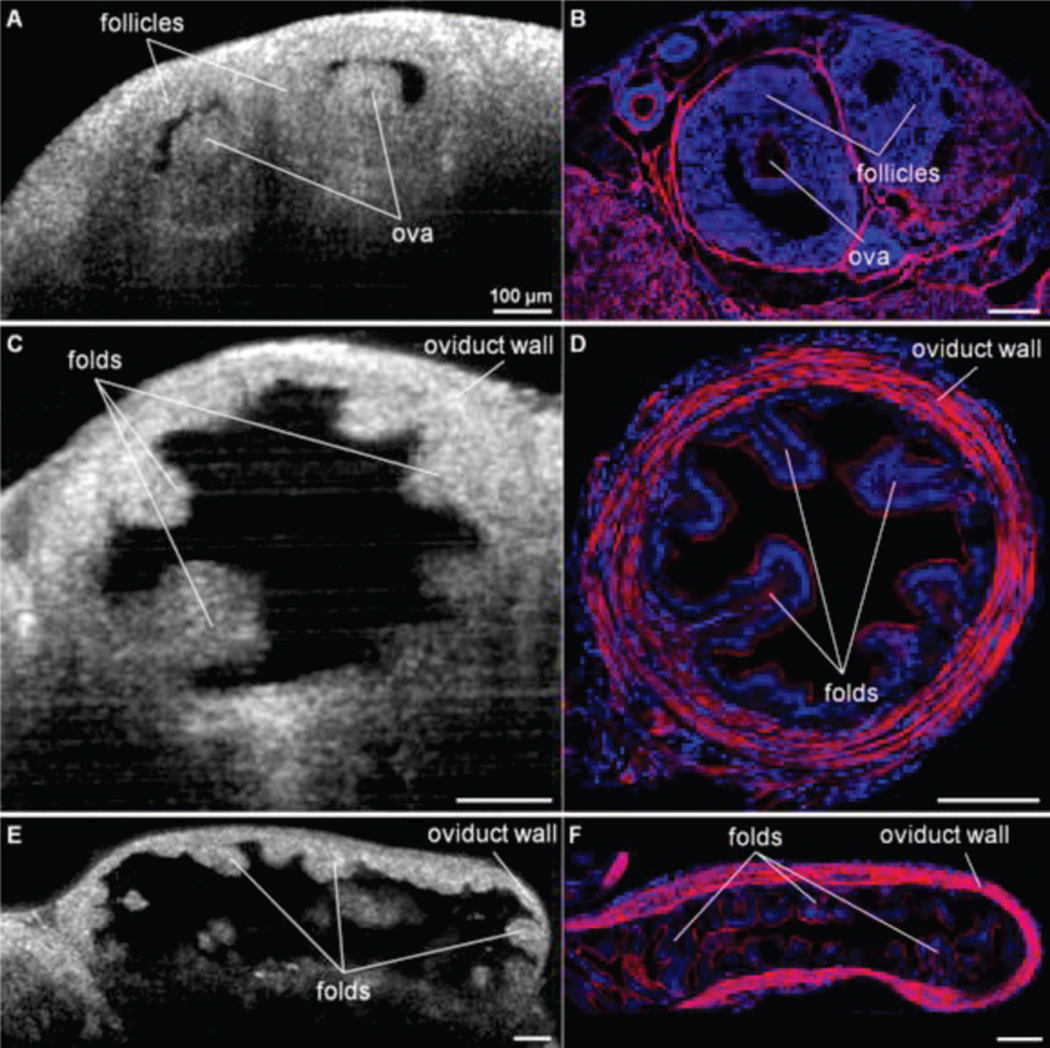

OCT has also been applied to visualize dynamic events in reproductive organs during ovulation, fertilization and pre-implantation stages of embryonic development. Mouse reproductive organs such as the uterus, the ovary and the oviduct were observed in vivo (Fig. 4) [42]. Key structural features such as follicles and corpora lutea in the ovary, oocytes and surrounding cumulus cells in oviduct ampulla and the folding pattern in oviduct isthmus were clearly seen with OCT, and were well correlated with histological images. Size of follicles and oocytes were also quantified [127]. Fine structures within pre-implantation stage mouse embryos such as meiotic spindles in oocytes and mitotic spindles in zygotes, nuclei, second polar bodies in zygotes, and cleavage planes in two-cell stage embryos were observed with OCT [128, 129]. These results demonstrated the feasibility of using OCT to observe embryos at the very early stage of development and would help further our understanding of fertility and infertility.

Fig. 4.

Cross-sectional OCT images (A, C, E) and histology (B, D, F) of the female mouse reproductive tract. (A, B) Follicles in the ovary. (C, D) Images across the oviduct showing the folds in the lumen. (E, F) Cross-section along the oviduct showing the folds of the oviduct arranged in nodules. All scale bars correspond to 100 µm. Images reproduced from reference [42] with permission.

OCT imaging of heart development

In vertebrate animals, the heart is one of the earliest organs to form and function during embryo development [130]. The embryonic heart undergoes dramatic morphological changes during development. Abnormal heart development may lead to congenital heart malformation [131]. OCT enables high resolution visualization and measurement of cardiac layers (e.g. myocardium, cardiac jelly, and endocardium) and fine structures (e.g. tethers connecting the endocardium to the myocardium) [132], as well as assessment of fast dynamics of a beating heart in vivo. Next, we focus our discussion on applications of OCT on heart development in various animal models, including Xenopus [11, 133–135], zebrafish [40, 136], avian [43, 137–144], mouse [44, 145–154]and Drosophila [45, 155–163].

Xenopus

The Xenopus is an ideal animal model for studying normal and abnormal cardiac development due to easy handling and partially transparency of Xenopus embryos [133, 164]. OCT has been used for evaluation of structures and functions in the developing cardiovascular system of Xenopus models. OCT imaging of stage 47 Xenopus embryonic heart was demonstrated in vivo [11]. Atrium septation and the formation of three-chamber (two atria and one ventricle) structure were observed, showing the final major step of heart formation in Xenopus embryos. Fine microstructural anatomical details such as myocardial walls, lumens, trabeculae carneae were visualized, demonstrating the micron-scale resolvability of OCT.

With video rate imaging speed, OCT was able to resolve different phases of the heart beat cycle in Xenopus model [133]. Relaxation and contraction of atria and the ventricle were visualized. Ventral and dorsal wall movement was imaged, which were used to measure end diastolic/systolic dimensions, heart rates and ejection fraction. Doppler OCT was used to monitor blood flow and cardiac wall motion in Xenopus hearts [133–135]. Outflow of blood through truncus arteriosis and inter-trabecular blood flows into ventricles were visualized in different cardiac cycles.

Zebrafish

Zebrafish is transparent in the embryonic and early larval stage, which allows for easy optical observation of cardiac development. Zebrafish can survive for a week without a functional cardiovascular system. This allows researchers to study the functional role of genes during cardiac development and the mechanism of severe cardiovascular defects in mutant models [165, 166]. OCT has been used to image the structure and function of zebrafish hearts at different developmental stages in vivo [40]. A two-chambered heart structure was observed within the pericardial wall of zebrafish embryos after 72 hours post-fertilization. An increase in heart chamber size and heart rate was observed throughout embryonic development. In addition, filling and contraction of the atrium and ventricle in larval heart was dynamically imaged with OCT [136]. Pulsatile flow patterns were observed within one cardiac cycle using Doppler OCT. Developmental cardiac defects were examined in mutant zebrafish embryos [40]. An enlarged pericardial cavity and underdeveloped heart were observed in nok m520 mutants at 72 hours post-fertilization when compared to normal embryos.

Avian

Embryos of avian models, such as chick and quail, were widely used to study cardiac development due to their similarity to human heart development. Moreover, avian embryos at specific developmental stages can be easily accessed after removing their eggshells [167]. OCT has been used to evaluate cardiac structural and functional development and characterize genesis and mechanisms of cardiac defects in avian models. Particularly, 4D gated OCT imaging was developed to study the morphological dynamics of the beating embryo heart in vivo [43]. Detailed motions of avian heart beat were observed during systole and diastole phases (Fig. 5) [137]. Physiologic parameters, such as stroke volume, cardiac output, ejection fraction, and wall thickness, were measured using the 4D gated OCT system [138–142]. Recently, OCT images and optical maps have been obtained simultaneously to form conduction mappings in early embryonic quail hearts [139]. This integrated system allowed for correlation between heart structure and electrophysiology [139]. Doppler OCT was used to identify radial strain and strain rate of the myocardial wall to understand the biomechanical characteristics in the chick embryonic heart [140]. Cardiac defects in avian embryos caused by ethanol exposure at the gastrulation stage were studied with OCT. These defects included muscular ventricular septal defects, missing or misaligned great vessels, double outlet right ventricle, to hypoplastic or abnormally rotated ventricles [143, 144].

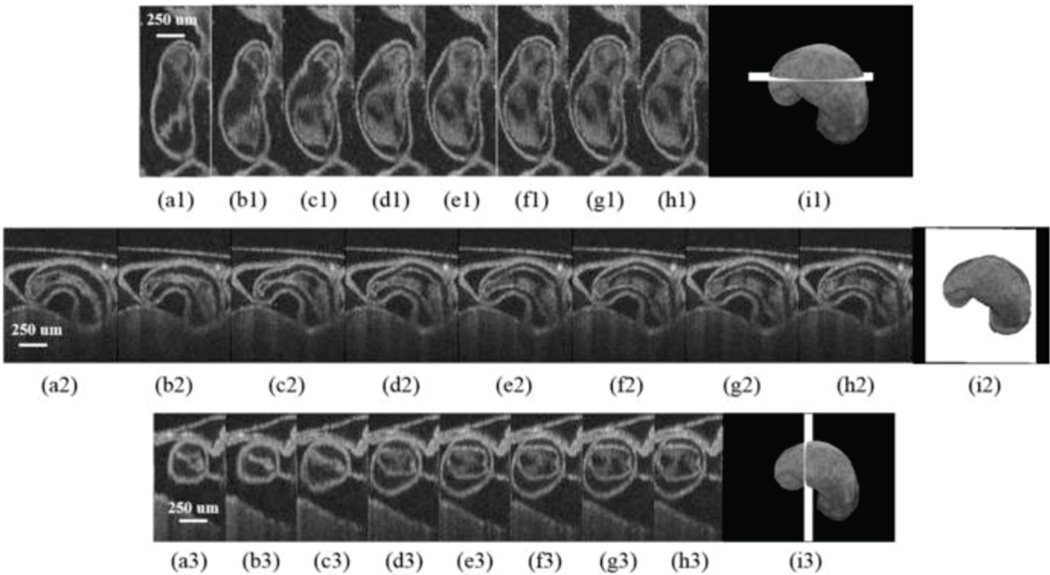

Fig. 5.

Eight phases of the beating embryonic quail heart (a–i) from three different orientations acquired in vivo using gated OCT. Each time series progresses from systole to diastole and each slice is separated by 95 ms. Row 1 presents en face 2D OCT images (sagittal to the body). Row 2 displays eight phases from the normal OCT view (coronal to the body), while row 3 shows the transverse view of the heart. Images on the far right show a 3D surface reconstruction of the heart in phase 8 (diastole). The white plane indicates the location of the preceding 2D OCT images. Images reproduced from reference [137] with permission.

Mouse

Mouse hearts are very similar to human hearts, apart from differences in size, heart rates and gestational period [168]. Anatomically, both mouse and human have four-chambered structure. Developmental events leading to atrial and ventricular septation are comparable, as well as the progression of myocardium and cardiac valves. With rapid development of transgenic technology, mouse models have been routinely used for understanding normal and abnormal cardiac development and efficient phenotyping of cardiac defects in humans [169].

OCT has been applied to evaluation of early stage cardiac development in mouse embryos. Hearts were visualized in OCT images of 7.5–10.5 days post coitum (dpc) mouse embryos [44, 145–148]. Main cardiac structures such as heart tube at 8.5 dpc [44]; primitive atrium and ventricle at 9.5 dpc [145, 148]; atrium, ventricles and atrioventricular cushions at 10.5 dpc [149] were visualized. Developmental events like heart looping were observed [147]. Dynamic imaging of one cardiac cycle was demonstrated at 8.5, 9.5, and 10.5 dpc [146, 148, 149]. During dynamic imaging, blood cell circulation, phase delay between beating atrium and ventricle, and progression of pulse wave in outflow tract wall were observed [148]. Angiograms and cardiac blood flows between the yolk sac and heart (via vitelline arteries and veins) and in dorsal aortae were measured within early stage mouse embryos in retracted uterus [149] or in embryo cultures [148, 150–152]. Pulsatile pattern of blood flow was measured to quantify heart rate of early stage embryos [151]. OCT images of mouse embryonic hearts during late stage cardiac development 12.5–17.5 dpc showed a clear four-chambered structure [145, 149]. Vascular structures such as septated aorta and pulmonary trunk were clearly seen. Phenotyping of cardiac defects using OCT were demonstrated in transgenic mouse embryos. In one study, small heart looping angles were observed in 8.5 dpc Wdr19 embryos, showing heart looping defects [147]. In another study, underdeveloped left atriums and ventricles and the missing of interventricular septum were observed in 12.5 and 13.5 dpc HEXIM1 mutants [153]. Measured chamber volumes and wall thicknesses showed large variations between mutant hearts and normal ones. Quantification of chamber volumes and wall thicknesses can be applied in study of transgenic adult mouse [154].

Drosophila melanogaster

Drosophila models are widely used for genetic and developmental biology studies with unique advantages. Over 75% human disease genes have orthologs in Drosophila [170]. The heart tube of Drosophila is located only ~200 µm below the surface of the fly back, and the body is relatively transparent during early development, making it possible to perform non-invasive imaging of the fly heart using OCT. Heart similarities of Drosophila to vertebrate were seen at early developmental stages [171, 172]. Molecular mechanisms and genetic pathways regulating heart development are conserved between Drosophila and vertebrates [173, 174]. Moreover, the short life cycle and low culturing cost facilitate wide use of the Drosophila models for scientific research. These unique advantages make Drosophila a powerful model system to study human heart diseases.

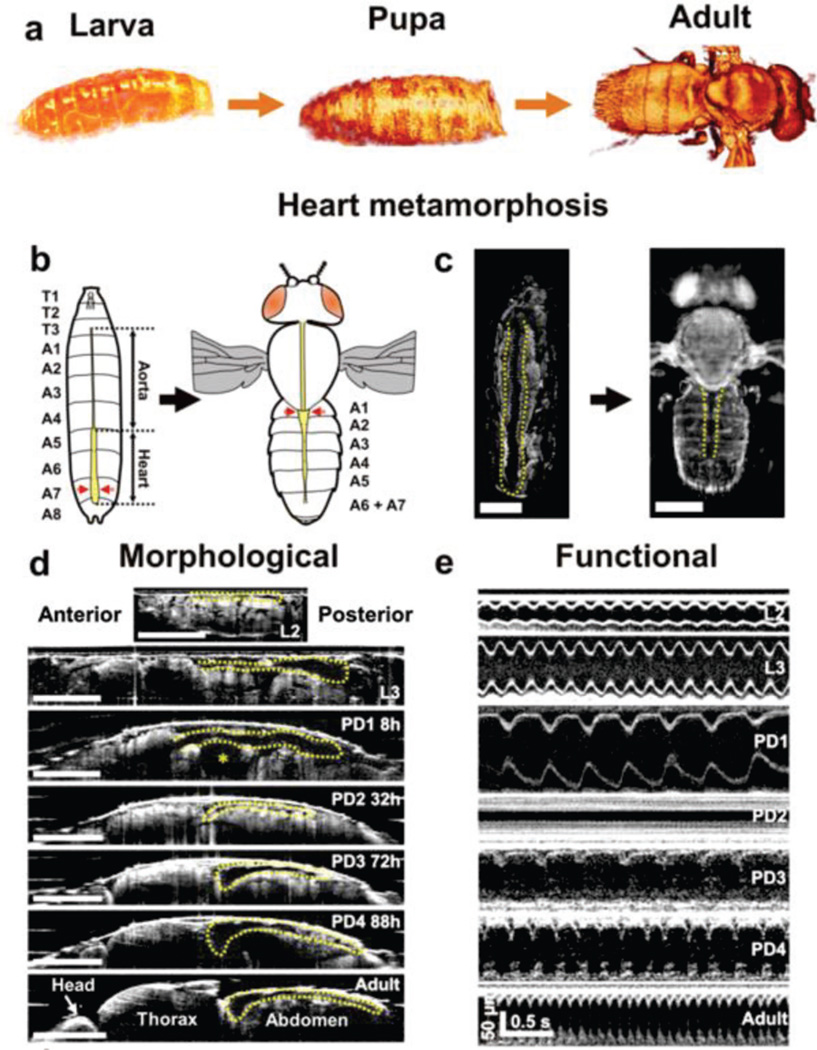

In 2006, OCT was used to characterize Drosophila heart function in vivo for the first time [156, 161]. Morphological and functional parameters, such as heart rate (HR), end systolic and diastolic diameters, fraction shortening, etc. were measured completely non-invasively. Since then, OCT has been utilized by several groups, including our group, to study Drosophila heart development [155, 157, 160, 175]. Heart chamber size, heart rate and beating behaviors of adult flies of different ages were compared [158, 160]. Retrograde and anterograde heart beats were observed in adult flies [158]. Additional parameters, such as heart wall thickness [160] and velocity [159], and cardiac activity period (CAP) [45] were found to be important metrics in characterizing Drosophila heart morphogenesis and function. Recently, our group used an ultrahigh resolution OCM system to perform non-invasive and longitudinal analysis of functional and morphological changes in the Drosophila heart throughout its post-embryonic lifecycle for the first time [45]. We observed that the heart of Drosophila exhibits major morphological and functional alterations during development. Notably, the Drosophila heart rate slows down in early pupa, stops beating for about a day (e.g. cardiac developmental diastasis), the heart rate increases in late pupa stages and reaches the maximum on adult day 1 (Fig. 6) [45]. CAP was introduced as the ratio of on-period (when fly heart beats) to the total imaging time. We observed that both Drosophila HR and CAP showed significant variations during the pupa stage, while heart remodeling took place [45].

Fig. 6.

3D and M-mode OCM imaging of post-embryonic Drosophila lifecycle. (A) 3D OCM renderings of a control 24B-GAL4/+ fly at larva, pupa and adult stages. (B) Schematic representation of heart metamorphosis. (C) En face OCM projections showing heart metamorphosis. (D) Axial OCM sections showing heart remodeling during Drosophila lifecycle. * denotes the air bubble location during early hours of pupa development. (E) M-mode images at different developmental stages showing heart rate changes across lifecycle. L2, 2nd instar larva; L3, 3rd instar larva; PD1-4, pupa day 1 through day 4. Scale bars in (C) and (D) represent 500 µm. Images reproduced from reference [45] with permission.

Drosophila has been widely used as a model organism in genetic studies of cardiovascular disease including heart failure and arrhythmia [161]. OCT has been used to non-invasively phenotype cardiac function throughout the Drosophila life cycle. OCT revealed severe heart defects associated with mutation of angiotensin converting enzyme-related gene in Drosophila [162]. Silencing the Drosophila ortholog of human presenilins (dPsn) led to significantly reduced HR and remarkable age-dependent increase in end-diastolic vertical dimensions [160]. Moreover, using transgenic Drosophila models, our group has found that alterations in expression of a highly conserved Drosophila ortholog of human SOX5 gene, Sox102F, led to enlarged and irregular heart tube, decreased HR and reduced cardiac wall velocity, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of multiple cardiac diseases or traits [163].

The Circadian rhythm gene dCry regulates heart development

Circadian rhythms are fundamental biological phenomena that recur regularly over approximately a 24-hour cycle and affect living beings ranging from tiny microbes to higher order animals including humans [176]. Circadian rhythms are also related to cardiovascular functions and pathologies [177]. Cardiovascular disorders, such as myocardial ischemia, acute myocardial infarction, sudden cardiac death and cardiac arrhythmias, were also demonstrated with clear circadian rhythm related temporal patterns [178]. Circadian rhythms are controlled by circadian clocks [179]. The architecture of mammal clock is highly conserved with Drosophila [180]. The Drosophila cryptochrome (dCry) encodes a major component of the circadian clock negative feedback loop [179, 181]. Recently, our group found that RNA silencing of the dCry in the Drosophila heart and mesoderm resulted in slower HR, decreased CAP, smaller heart chamber size, pupal lethality and segment polarity related phenotypes, which indicate that dCry plays an essential role in heart morphogenesis and function [45].

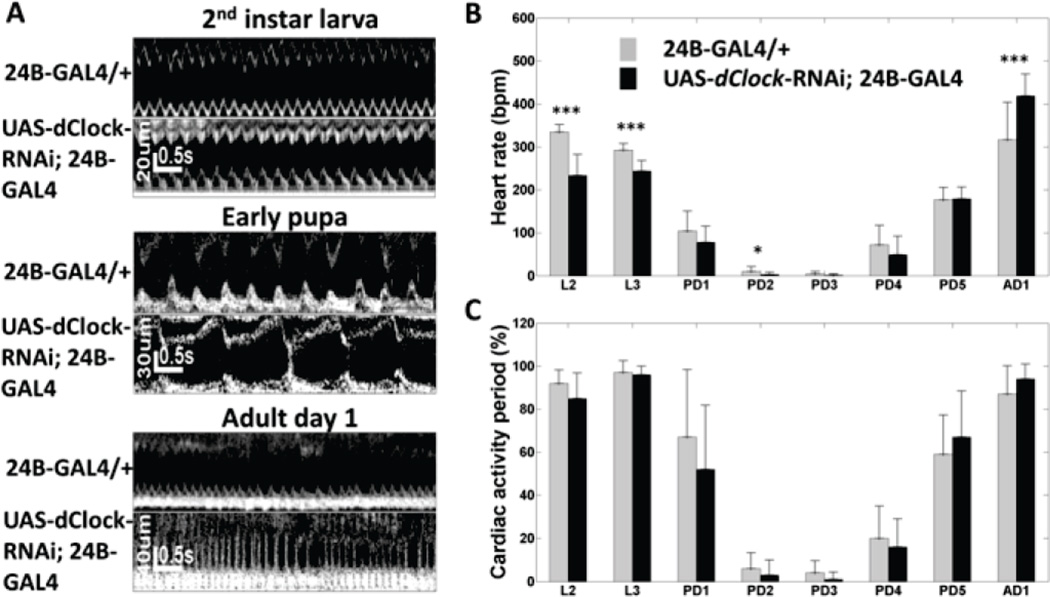

Silencing another circadian gene, dClock, resulted in altered HR and CAP

The circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (Clock) is another crucial gene in the circadian clock feedback loop. It encodes CLOCK protein which plays a central role in regulating circadian rhythms [179]. Clock has been found to be necessary for normal cardiac function [182]. However, the functional role of Clock gene in cardiac development has not been confirmed. As a follow up study of the association between the circadian gene Cry and heart development, we have recently examined the effect of another circadian gene Clock on HR and CAP in Drosophila. The ortholog of human Clock gene in Drosophila is dClock. In this study, the dClock was silenced by RNAi using the UAS-GAL4 system. The UAS-dClock flies were mated with the 24B–GAL4 driver flies (UAS-dClock-RNAi; 24B–GAL4, abbreviated as dClock-RNAi). Flies that expressed a heterozygous 24B–GAL4 driver alone were used as control (24B–GAL4/+). HR and CAP of all the flies were measured every 24 hours from the 2nd instar larva (L2), to 3rd instar larva (L3), pupa day 1–5 (PD1–5), and adult day 1 (AD1), respectively. Number of flies measured at each developmental stage is listed in Table 1.

TABLE I.

Number of Flies in Each Experimental Group at Various Developmental Stages

| Fly groups / Developmental stages | L2 | L3 | PD1 | PD2 | PD3 | PD4 | PD5 | AD1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24B-GAL4/+ | 10 | 10 | 19 | 18 | 19 | 11 | 9 | 16 |

| UAS-dClock-RNAi; 24B-GAL4 | 15 | 13 | 11 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 12 |

| 24B-GAL4-HFD | 26 | 20 | 17 | 18 | 15 | 18 | 12 | 14 |

L2, 2nd instar larva; L3, 3rd instar larva; PD1-5, pupa day 1 through 5; AD1, adult day 1

Fig. 7A shows representative M-mode images of control and dClock-RNAi flies at 2nd instar larva, early pupa and adult day 1. Slower heartbeat at larva and early pupa stages, and faster heartbeat on AD1 were observed in dClock-RNAi flies (Fig. 7B). In the control flies, the HR decreased from 355 ± 16 beating per minute (bpm) on L2 to 4 ± 5 bpm on PD3, and then increased to 317 ± 86 bpm on AD1. In dClock-RNAi flies, HR changed from 234 ± 48 bpm at L2 to 1 ± 3 bpm on PD3, and then increased to 418 ± 51 bpm at AD1. Significant slower HR (p < 0.05) were observed in dCock-RNAi flies compared to controls at L2, L3 and early pupa stages, while the HR was significantly higher in dCock-RNAi flies on AD1 (p < 0.05). CAP, in both groups (Fig. 7C), decreased significantly when the flies developed into pupa. From PD4, CAP started to increase and returned to ~97% on AD1. No significant differences were observed in CAP between dCock-RNAi and control flies. Collectively, RNAi silencing of dClock gene resulted in significant difference in HR at various developmental stages. These findings indicated that dClock affects heart development. The regulatory effects of two circadian genes, Cry and Clock, affirmed the important role of the circadian genes on heart development and function.

Fig. 7.

Evaluation of the effect of a circadian gene, dClock, on Drosophila heart development. (A) M-mode OCM images of 24B-GAL4/+ control and UAS-dClock-RNAi; 24B-GAL4 flies at 2nd instar larva, early pupa and adult day 1. Comparison of heart rate (B) and cardiac activity period (C) between 24B-GAL4/+ control and UAS-dClock-RNAi; 24B-GAL4 flies from 2nd instar larva to adult day 1. * denote significant difference between control and UAS-dClock-RNAi; 24B-GAL4 flies (p < 0.05); **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

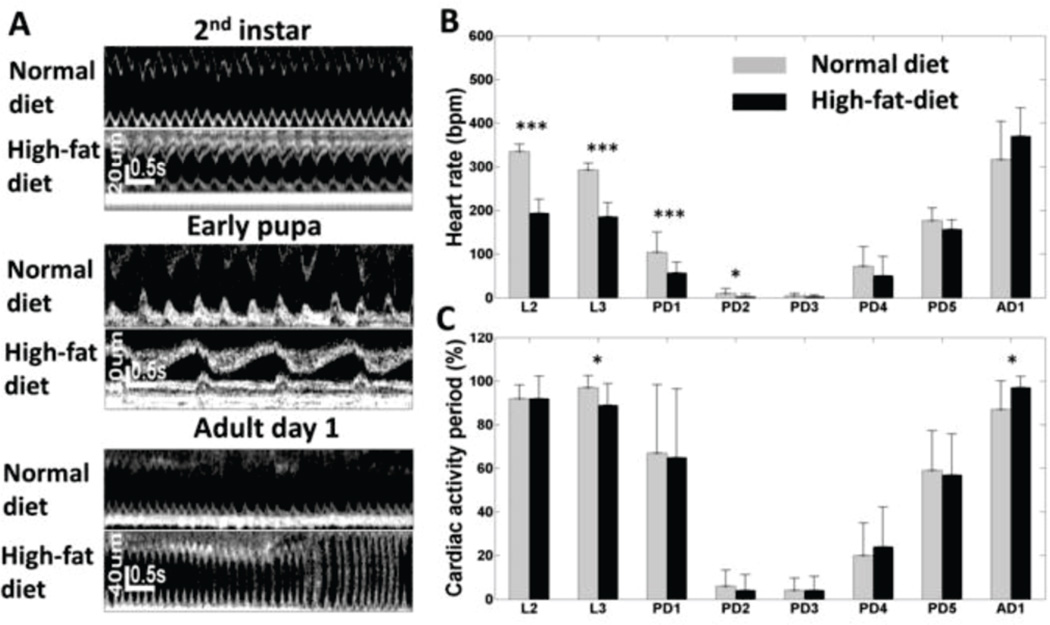

OCT imaging to evaluate the effect of HFD on Drosophila heart development

It was demonstrated that accumulation of lipids greatly increases the risks of diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer [183, 184]. The incidence of obesity induced by lipid accumulation has been growing globally with the increase in the overweight adult population which has reached over 1.5 billion [170]. Investigating obesity induced cardiac diseases in animals contributes to understanding and treatment of obesity related human cardiac diseases. Calorically rich high-fat diet has been revealed as a major contributor to diabetes and cardiovascular disease [185]. A variety of animal models have been used to study HFD-associated cardiac diseases [186–189]. Drosophila models have been used for HFD study due to the conserved response mechanism to HFD as in humans [173, 174]. The origin of HFD induced obesity was previously studied by analyzing cardio toxic and metabolic phenotypes, and genetic mediators in adult flies [170]. A better understanding of the formation and progression of heart diseases induced by HFD at a variation of developmental stages would provide insights about cardiac disease mechanisms and pathogenesis.

In this study, we fed 24B–GAL4/+ flies with HFD and compared heart function of these flies with control flies (24B–GAL4/+) fed with normal diet. HFD were prepared with a weight ratio 30% of coconut oil (organic extra virgin coconut oil with 22% fat) to standard fly food [170]. Number of flies measured at each developmental stage is listed in Table 1.

Fly heart phenotypes at different developmental stages were compared between flies fed with high-fat-diet and normal diet. Fig. 8A shows representative M-mode OCM images at 2nd instar larva, early pupa and adult day 1. Interestingly, as shown in Fig. 8B, significantly lower HR (p < 0.05) was observed in flies fed with high-fat-diet at early developmental stages, including larva (L2 and L3) and early pupa (PD1 and PD2). The HR was similar in both groups in late pupa stages and on adult day 1. On the other hand, CAP of the two groups showed similar trends as flies developed, except that significant differences (p < 0.05) were only observed at L3 and AD 1 stages. The HR and CAP changes observed in flies fed with HFD suggested that HFD induced cardiac functional defect, especially at early developmental stages. Further studies are needed in order to understand the underline molecular mechanisms and genetic pathways involved in the process.

Fig. 8.

Evaluation of the effect of high-fat-diet (HFD) on Drosophila heart development. (A) M-mode OCM images of flies (24B-GAL4/+) fed with normal diet (ND) and HFD at 2nd instar larva, early pupa and adult day 1. Comparison of heart rate (B) and cardiac activity period (C) between flies fed with normal diet and high-fat-diet from 2nd instar larva to adult day 1. * denote significant difference between normal diet and high-fat-diet groups (p < 0.05); **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

IV. DISCUSSION AND OUTLOOK

One limitation of OCT is the shallow imaging depth. In most biological tissues, OCT can only image up to 1–2 mm below surface. Optical clearing techniques, which utilize chemicals to achieve tissue refractive index matching [82, 190–196], can effectively improve imaging depth in highly scattering biological tissues. Optical clearing has been used in combination with light sheet microscopy [191, 192], confocal microscopy [82, 193], multi-photon microscopy [82, 190, 193], epifluorescence imaging [194] and optical projection tomography [197]. It has also been used with OCT in dermatology [198, 199] and ophthalmology [200]. Combining optical clearing with OCT imaging would help extend the needed imaging depth for brain research and developmental biology. However, most of the optical clearing methods to date are irreversible and invasive. Development of optical clearing method suitable for in vivo applications [201] would be of great value for OCT imaging.

High imaging speed is greatly desired for imaging fast dynamics in the brain and developing embryos. With rapid development of tunable laser sources, ultrahigh speed OCT imaging beyond 1 megahertz is becoming readily available based on swept-source OCT technologies [202–205]. Ultrahigh speed imaging of human eyes [206–210], fingers [211] as well as small animals such as Daphnia [212] has been demonstrated at up to 20M A-scans/s. Another approach to achieve significant improvement in OCT imaging speed is to use parallel imaging. Recently developed space-division multiplexing OCT (SDM-OCT) technique [213] and interleaved OCT (iOCT) technique [214–216] have demonstrated great promises. Further improvement of OCT imaging speed can be expected by combining the development of high speed tunable lasers and parallel imaging techniques. The unprecedented imaging speed makes OCT very attractive for 4D imaging of fast dynamic processes in biological samples, such as in a beating heart [148].

Multimodal imaging combines advantages of different imaging technologies in order to obtain complementary information of biological systems [2]. OCM has been combined with two-photon microscopy [217] to provide high-resolution registered images of brain patterning and morphogenesis in live zebrafish embryos. OCT has also been combined with photoacoustic tomography to image tissue optical scattering and absorption profiles simultaneously [218, 219]. A multimodal imaging system integrating OCT with two photon and confocal microscopy, optical intrinsic signal imaging, and laser speckle imaging, was recently reported to characterize multiple parameters of cerebral oxygen delivery and energy metabolism, including microvascular blood flow, oxygen partial pressure, and NADH autofluorescence [220]. Cost-effective, easy-to-use multimodal imaging systems will surely be valuable to image the brain and developing animals.

OCT imaging is non-invasive. Combining OCT with non-invasive stimulation or perturbation of biological systems would make an attractive research platform. Recent development of optogenetic tools [221–223] makes it possible to achieve optical stimulation and imaging of the brain and the heart completely non-invasively. Very recently, OCT has been used to monitor hemodynamic changes following optogenetic stimulation in transgenic mouse brain [96]. Our group demonstrated simultaneous optogenetic pacing and ultrahigh resolution OCT imaging in Drosophila heart at different developmental stages of the specimens, including larva, pupa and adult stages [224]. More exciting research activities can be expected utilizing non-invasive OCT imaging and optogenetic stimulation to further our understanding of the brain and heart development.

V. CONCLUSIONS

In summary, OCT provides three dimensional images of biological samples without the need for tissue excision and processing. OCT enables label-free evaluation of morphological and functional information of the brain and developing embryos with micrometer resolutions and video rate imaging speed. Further development to achieve higher speed and multi-functionality imaging will further enhance the capability of OCT. Combined with optical clearing and optogenetic technologies; it would make a powerful research platform for brain research and developmental biology.

Acknowledgments

This work is partially supported by Lehigh University Start-up Fund, NIH grants R00EB010071, R15EB019704, R21EY026380, R03AR063271, R01MH060009 and R01AG014713, and NSF grant 1455613.

Biographies

Jing Men received her B.S degree at Northeast Normal University in China in 2010, and then graduated from Peking University in 2014 (M.S). Currently, she is a PhD student in the Bioengineering program of Lehigh University in the USA. Her current research interests include OCT imaging in developmental biology and optogenetic pacing in fruit flies.

Yongyang Huang received his B.S. degree in physics from Peking University in 2013. He is currently a PhD student at Lehigh University. His current research interests include developing ultrahigh-speed OCT system and utilizing OCT system for various biomedical applications.

Jitendra Solanki received his B.Sc., M.Sc. and PhD degrees in Physics from the Devi Ahilya University, India, in 2005, 2007 and 2014, respectively. He is experienced in the field of OCT and biosensors, particularly O2 and glucose sensors. He is currently a post-doctoral associate at Lehigh University.

Xianxu Zeng graduated from China Medical University (MD, 2006). She is currently the Associate Chief Physician and Deputy Director of Pathology at the Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University. She was a visiting scientist at Lehigh University in 2013–2014.

Aneesh Alex graduated from Cochin University of Science and Technology, Kerala, India (Integrated M.Sc. in Photonics, 2007), obtained his Ph.D. degree in Biomedical optics from the Cardiff University, Wales, UK (2011), and received post-doctoral training from Medical University Vienna, Austria and Lehigh University, PA, United States. He is currently a research fellow at GlaxoSmithKline Plc. He is a member of the International Society for Optical Engineering (SPIE), Optical Society of America (OSA) and American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists (AAPS).

Jason Jerwick graduated from Lehigh University (B.S. 2015) and is a current graduate student in Electrical Engineering at Lehigh University.

Zhan Zhang (MD, PhD) graduated from Tongji University in China. She is currently a Professor of Medicine at Zhengzhou University. She is a member of the standing committee of Inspection Branch of Chinese Medical Association, and a member of Henan Medical Association, Henan Preventive Medicine Association. She is also the Chairman of Inspection Branch and Microorganism and Immunity Branch of Henan Medical Association.

Rudolph E. Tanzi obtained his PhD from Harvard University in 1990 and is currently the Joseph P. and Rose F. Kennedy Professor of Neurology at Harvard Medical School. At Massachusetts General Hospital, Dr. Tanzi serves as Vice-Chair of Neurology and Director of the Genetics and Aging Research Unit. He is a fellow of the American Academy for the Advancement of Science Fellow, and was won the Potamkin Prize, the Metropolitan Life Award, and the Smithsonian American Ingeniuty Award for his research on Alzheimer’s disease.

Airong Li obtained her PhD from University of Oxford School of Medicine in 1996 and completed a post-doctoral training at Yale University School of Medicine. She is currently an assistant professor of Neurology at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Li is a member of American Society of Human Genetics, Genetics Society of America, and Society for Neurosciences and Project Management Institute.

Chao Zhou graduated from Peking University in China (B.S., 2001), obtained his Ph.D. degree from the University of Pennsylvania (2007), and received post-doctoral training from Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He is currently a P. C. Rossin assistant professor in electrical engineering and bioengineering at Lehigh University. He is a member of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), International Society for Optical Engineering (SPIE), Optical Society of America (OSA), American Heart Association (AHA), and the International Society for Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism (ISCBFM).

Contributor Information

Jing Men, Email: jim614@lehigh.edu, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Center for Photonics and Nanoelectronics, and Bioengineering Program, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, USA, 18015.

Yongyang Huang, Email: yoh213@lehigh.edu, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Center for Photonics and Nanoelectronics, and Bioengineering Program, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, USA, 18015.

Jitendra Solanki, Email: jis915@lehigh.edu, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Center for Photonics and Nanoelectronics, and Bioengineering Program, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, USA, 18015.

Xianxu Zeng, Email: xianxu77@163.com, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Center for Photonics and Nanoelectronics, and Bioengineering Program, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, USA, 18015; Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan, P.R. China, 450000.

Aneesh Alex, Email: aneeshalexp@gmail.com, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Center for Photonics and Nanoelectronics, and Bioengineering Program, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, USA, 18015.

Jason Jerwick, Email: jrj215@lehigh.edu, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Center for Photonics and Nanoelectronics, and Bioengineering Program, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, USA, 18015.

Zhan Zhang, Email: zhangzhanmd27@126.com, Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan, P.R. China, 450000.

Rudolph E. Tanzi, Email: tanzi@helix.mgh.harvard.edu, Genetics and Aging Research Unit, Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA, 02129.

Airong Li, Email: ALI3@mgh.harvard.edu, Genetics and Aging Research Unit, Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA, 02129.

Chao Zhou, Email: chaozhou@lehigh.edu, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Center for Photonics and Nanoelectronics, and Bioengineering Program, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, USA, 18015.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huang D, Swanson EA, Lin CP, et al. Optical Coherence Tomography. Science. 1991 Nov 22;254:1178–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.1957169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drexler W, Liu M, Kumar A, et al. Optical coherence tomography today: speed, contrast, and multimodality. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2014;19:071412. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.19.7.071412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wojtkowski M. High-Speed optical coherence tomography: basic and applications. Appl. Opt. 2010;49:D30–D61. doi: 10.1364/AO.49.000D30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potsaid B, Gorczynska I, Srinivasan VJ, et al. Ultrahigh speed Spectral / Fourier domain OCT ophthalmic imaging at 70,000 to 312,500 axial scans per second. Optics Express. 2008;16:15149–15169. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.015149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nassif N, Cense B, Park B, et al. In vivo high-resolution video-rate spectral-domain optical coherence tomography of the human retina and optic nerve. Optics Express. 2004;12:367–376. doi: 10.1364/opex.12.000367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konstantopoulos A, Hossain P, Anderson DF. Recent advances in ophthalmic anterior segment imaging: a new era for ophthalmic diagnosis? The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2007;91:551–557. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.103408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antcliff RJ, Spalton DJ, Stanford MR, et al. Intravitreal triamcinolone for uveitic cystoid macular edema: An optical coherence tomography study. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:765–772. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00658-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guedes V, Schuman JS, Hertzmark E, et al. Optical coherence tomography measurement of macular and nerve fiber layer thickness in normal and glaucomatous human eyes. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:177–189. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01564-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung CKS, Cheung CYL, Weinreb RN, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer imaging with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography a variability and diagnostic performance study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1257–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Velthoven MEJ, Faber DJ, Verbraak FD, et al. Recent developments in optical coherence tomography for imaging the retina. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2007 Jan;26:57–77. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boppart SA, Tearney GJ, Bouma BE, et al. Noninvasive assessment of the developing xenopus cardiovascular system using optical coherence tomography. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:4256–4261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jang IK, Bouma BE, Kang D-H, et al. Visualization of coronary atherosclerotic plaques in patients using optical coherence tomography: comparison with intravascular ultrasound. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;39:604–609. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01799-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jang IK, Tearney GJ, MacNeill B, et al. In vivo characterization of coronary atherosclerotic plaque by use of optical coherence tomography. Circulation. 2005;111:1551–1555. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000159354.43778.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tearney GJ, Waxman S, Shishkov M, et al. Three-dimensional coronary artery microscopy by intracoronary optical frequency domain imaging. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2008;1:752–761. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suter MJ, Nadkarni SK, Weisz G, et al. Intravascular optical imaging technology for investigating the coronary artery. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2011;4:1022–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tearney GJ, Brezinski ME, Fujimoto JG, et al. Scanning single-mode fiber optic catheter-endoscope for optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 1996;21:543–545. doi: 10.1364/ol.21.000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li XD, Boppart SA, Van Dam J, et al. Optical coherence tomography: Advanced technology for the endoscopic imaging of Barrett's esophagus. Endoscopy. 2000;32:921–930. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang TD, Van Dam J. Optical biopsy: A new frontier in endoscopic detection and diagnosis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2004;2:744–753. doi: 10.1053/S1542-3565(04)00345-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tearney GJ, Brezinski ME, Southern JF, et al. Optical biopsy in human gastrointestinal tissue using optical coherence tomography. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1997;92:1800–1804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sivak MV, Kobayashi K, Izatt JA, et al. High-resolution endoscopic imaging of the GI tract using optical coherence tomography. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2000;51:474–479. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70450-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouma BE, Tearney GJ, Compton CC, et al. High-resolution imaging of the human esophagus and stomach in vivo using optical coherence tomography. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2000;51:467–474. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Izatt JA, Kulkarni MD, Wang HW, et al. Optical coherence tomography and microscopy in gastrointestinal tissues. Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, IEEE Journal of. 1996;2:1017–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tearney GJ, Brezinski ME, Bouma BE, et al. In vivo endoscopic optical biopsy with optical coherence tomography. New Series. 1997;276:2037–2039. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitt JM, Yadlowsky MJ, Bonner RF. Subsurface imaging of living skin with optical coherence microscopy. Dermatology. 1995;191:93–98. doi: 10.1159/000246523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welzel J. Optical coherence tomography in dermatology: a review. Skin Research and Technology. 2001;7:1–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0846.2001.007001001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pierce MC, Strasswimmer J, Park BH, et al. Advances in optical coherence tomography imaging for dermatology. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2004;123:458–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mogensen M, Morsy HA, Thrane L, et al. Morphology and epidermal thickness of normal skin imaged by optical coherence tomography. Dermatology. 2008 doi: 10.1159/000118508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welzel J, Lankenau E, Birngruber R, et al. Optical coherence tomography of the human skin. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1997;37:958–963. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gambichler T, Moussa G, Sand M, et al. Applications of optical coherence tomography in dermatology. Journal of Dermatological Science. 2005;40:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choma M, Sarunic M, Yang C, et al. Sensitivity advantage of swept source and Fourier domain optical coherence tomography. Optics Express. 2003;11:2183–2189. doi: 10.1364/oe.11.002183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Boer JF, Cense B, Park BH, et al. Improved signal-to-noise ratio in spectral-domain compared with time-domain optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2003;28:2067–2069. doi: 10.1364/ol.28.002067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leitgeb R, Hitzenberger C, Fercher A. Performance of fourier domain vs. time domain optical coherence tomography. Optics Express. 2003;11:889–894. doi: 10.1364/oe.11.000889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drexler W, Morgner U, Ghanta RK, et al. Ultrahigh-resolution ophthalmic optical coherence tomography. Nature medicine. 2001;7:502–507. doi: 10.1038/86589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leahy C, Radhakrishnan H, Srinivasan VJ. Volumetric imaging and quantification of cytoarchitecture and myeloarchitecture with intrinsic scattering contrast. Biomedical Optics Express. 2013;4:1978–1990. doi: 10.1364/BOE.4.001978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kut C, Chaichana KL, Xi J, et al. Detection of human brain cancer infiltration ex vivo and in vivo using quantitative optical coherence tomography. Science Translational Medicine. 2015;7:292ra100–292ra100. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Srinivasan VJ, Mandeville ET, Can A, et al. Multiparametric, longitudinal optical coherence tomography imaging reveals acute injury and chronic recovery in experimental ischemic stroke. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e71478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chong SP, Merkle CW, Leahy C, et al. Cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) assessed by combined Doppler and spectroscopic OCT. Biomedical Optics Express. 2015;6:3941–3951. doi: 10.1364/BOE.6.003941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akkin T, Davé D, Milner T, et al. Detection of neural activity using phase-sensitive optical low-coherence reflectometry. Optics Express. 2004;12:2377–2386. doi: 10.1364/opex.12.002377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rao KD, Verma Y, Patel HS, et al. Non-invasive ophthalmic imaging of adult zebrafish eye using optical coherence tomography. Current science. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kagemann L, Ishikawa H, Zou J, et al. Repeated, noninvasive, high resolution spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging of zebrafish embryos. Molecular Vision. 2008;14:2157–2170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Syed SH, Larin KV, Dickinson ME, et al. Optical coherence tomography for high-resolution imaging of mouse development in utero. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2011;16:046004. doi: 10.1117/1.3560300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burton JC, Wang S, Stewart CA, et al. High-resolution three-dimensional in vivo imaging of mouse oviduct using optical coherence tomography. Biomedical Optics Express. 2015;6:2713–2723. doi: 10.1364/BOE.6.002713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jenkins MW, Adler DC, Gargesha M, et al. Ultrahigh-speed optical coherence tomography imaging and visualization of the embryonic avian heart using a buffered Fourier Domain Mode Locked laser. Optics express. 2007;15:6251–6267. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.006251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larin KV, Larina IV, Liebling M, et al. Live imaging of early developmental processes in mammalian embryos with optical coherence tomography. Journal of innovative optical health sciences. 2009;02:253–259. doi: 10.1142/S1793545809000619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alex A, Li A, Zeng X, et al. A circadian clock gene, cry, affects heart morphogenesis and function in drosophila as revealed by optical coherence microscopy. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0137236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Despres JP. Body fat distribution and risk of cardiovascular disease: an update. Circulation. 2012;126:1301–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.067264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park JK, Lim YH, Kim KS, et al. Body fat distribution after menopause and cardiovascular disease risk factors: Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;22:587–94. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.4035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heinrichsen ET, Zhang H, Robinson JE, et al. Metabolic and transcriptional response to a high-fat diet in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Metab. 2013 Feb;3:42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hillman EMC. Coupling mechanism and significance of the BOLD signal: A status report. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2014;37:161–181. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071013-014111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petersen SE, Sporns O. Brain networks and cognitive architectures. Neuron. 2015;88:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Power JD, Cohen AL, Nelson SM, et al. Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron. 2011;72:665–678. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baillet S, Mosher JC, Leahy RM. Electromagnetic brain mapping. Signal Processing Magazine, IEEE. 2001;18:14–30. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bullmore ET, Sporns O. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10:186–198. doi: 10.1038/nrn2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hämäläinen M, Hari R, Ilmoniemi RJ, et al. Magnetoencephalography—theory, instrumentation, and applications to noninvasive studies of the working human brain. Reviews of Modern Physics. 1993;65:413–497. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Michel CM, Murray MM, Lantz G, et al. EEG source imaging. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2004;115:2195–2222. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rodriguez E, George N, Lachaux JP, et al. Perception's shadow: long-distance synchronization of human brain activity. Nature. 1999;397:430–433. doi: 10.1038/17120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Viventi J, Kim DH, Vigeland L, et al. Flexible, foldable, actively multiplexed, high-density electrode array for mapping brain activity in vivo. Nature Neuroscience. 2011;14:1599–1605. doi: 10.1038/nn.2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim SA, Jun SB. In-vivo optical measurement of neural activity in the brain. Experimental Neurobiology. 2013;22:158–166. doi: 10.5607/en.2013.22.3.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akkin T, Landowne D, Sivaprakasam A. Detection of neural action potentials using optical coherence tomography: intensity and phase measurements with and without dyes. Frontiers in Neuroenergetics. 2010;2 doi: 10.3389/fnene.2010.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Helmchen F, Denk W. Deep tissue two-photon microscopy. Nat Methods. 2005;2:932–40. doi: 10.1038/nmeth818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ohki K, Chung S, Ch'ng YH, et al. Functional imaging with cellular resolution reveals precise micro-architecture in visual cortex. Nature. 2005;433:597–603. doi: 10.1038/nature03274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang JW, Wong AM, Flores J, et al. Two-photon calcium imaging reveals an odor-evoked map of activity in the fly brain. Cell. 2003;112:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brazelton TR, Rossi FMV, Keshet GI, et al. From marrow to brain: Expression of neuronal phenotypes in adult mice. Science. 2000;290:1775–1779. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stosiek C, Garaschuk O, Holthoff K, et al. In vivo two-photon calcium imaging of neuronal networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:7319–7324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232232100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Okubo Y, Sekiya H, Namiki S, et al. Imaging extrasynaptic glutamate dynamics in the brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:6526–6531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913154107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kleinfeld D, Mitra PP, Helmchen F, et al. Fluctuations and stimulus-induced changes in blood flow observed in individual capillaries in layers 2 through 4 of rat neocortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1998;95:15741–15746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nishimura N, Schaffer CB, Friedman B, et al. Targeted insult to subsurface cortical blood vessels using ultrashort laser pulses: three models of stroke. Nat Meth. 2006;3:99–108. doi: 10.1038/nmeth844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xie Y, Bonin T, Löffler S, et al. Coronal in vivo forward-imaging of rat brain morphology with an ultra-small optical coherence tomography fiber probe. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2013;58:555–568. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/3/555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sun J, Lee SJ, Wu L, et al. Refractive index measurement of acute rat brain tissue slices using optical coherence tomography. Optics Express. 2012;20:1084–1095. doi: 10.1364/OE.20.001084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nakaji H, Kouyama N, Muragaki Y, et al. Localization of nerve fiber bundles by polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2008;174:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang H, Black AJ, Zhu J, et al. Reconstructing micrometer-scale fiber pathways in the brain: Multi-contrast optical coherence tomography based tractography. NeuroImage. 2011;58:984–992. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Srinivasan VJ, Sakadžić S, Gorczynska I, et al. Quantitative cerebral blood flow with optical coherence tomography. Optics Express. 2010;18:2477–2494. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.002477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Srinivasan VJ, Jiang JY, Yaseen MA, et al. Rapid volumetric angiography of cortical microvasculature with optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2010;35:43–45. doi: 10.1364/OL.35.000043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chong SP, Merkle CW, Leahy C, et al. Quantitative microvascular hemoglobin mapping using visible light spectroscopic Optical Coherence Tomography. Biomedical Optics Express. 2015;6:1429–1450. doi: 10.1364/BOE.6.001429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leitgeb RA, Villiger M, Bachmann AH, et al. Extended focus depth for Fourier domain optical coherence microscopy. Optics Letters. 2006;31:2450–2452. doi: 10.1364/ol.31.002450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li F, Xu T, Nguyen D-HT, et al. Label-free evaluation of angiogenic sprouting in microengineered devices using ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence microscopy. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2014;19:016006. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.19.1.016006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Srinivasan VJ, Radhakrishnan H, Jiang JY, et al. Optical coherence microscopy for deep tissue imaging of the cerebral cortex with intrinsic contrast. Optics Express. 2012;20:2220–2239. doi: 10.1364/OE.20.002220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li F, Song Y, Dryer A, et al. Nondestructive evaluation of progressive neuronal changes in organotypic rat hippocampal slice cultures using ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence microscopy. Neurophotonics. 2014;1:025002–025002. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.1.2.025002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Assayag O, Grieve K, Devaux B, et al. Imaging of non-tumorous and tumorous human brain tissues with full-field optical coherence tomography. NeuroImage. Clinical. 2013;2:549–557. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Magnain C, Augustinack JC, Konukoglu E, et al. Optical coherence tomography visualizes neurons in human entorhinal cortex. Neurophotonics. 2015;2:015004–015004. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.2.1.015004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ben Arous J, Binding J, Léger JF, et al. Single myelin fiber imaging in living rodents without labeling by deep optical coherence microscopy. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2011;16:116012–1160129. doi: 10.1117/1.3650770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hama H, Kurokawa H, Kawano H, et al. Scale: a chemical approach for fluorescence imaging and reconstruction of transparent mouse brain. Nature Neuroscience. 2011;14:1481–1488. doi: 10.1038/nn.2928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hee MR, Swanson EA, G Fujimoto J, et al. Polarization-sensitive low-coherence reflectometer for birefringence characterization and ranging. Journal of the Optical Society of America B. 1992;9:903–908. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hitzenberger CK, Götzinger E, Sticker M, et al. Measurement and imaging of birefringence and optic axis orientation by phase resolved polarization sensitive optical coherence tomography. Optics Express. 2001;9:780–790. doi: 10.1364/oe.9.000780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ding Z, Liang C-P, Chen Y. Technology developments and biomedical applications of polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography. Frontiers of Optoelectronics. 2015;8:128–140. [Google Scholar]

- 86.De Boer JF, Srinivas SM, Park BH, et al. Polarization effects in optical coherence tomography of various biological tissues. Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, IEEE Journal of. 1999;5:1200–1204. doi: 10.1109/2944.796347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Devor A, Sakadžić S, Srinivasan VJ, et al. Frontiers in optical imaging of cerebral blood flow and metabolism. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2012;32:1259–1276. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen Z, Zhao Y, Srinivas SM, et al. Optical Doppler tomography. Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, IEEE Journal of. 1999;5:1134–1142. doi: 10.1109/2944.796347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jonathan E, Enfield J, Leahy MJ. Correlation mapping method for generating microcirculation morphology from optical coherence tomography (OCT) intensity images. Journal of Biophotonics. 2011;4:583–587. doi: 10.1002/jbio.201000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mariampillai A, Standish BA, Moriyama EH, et al. Speckle variance detection of microvasculature using swept-source optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2008;33:1530–1532. doi: 10.1364/ol.33.001530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang RK, Jacques SL, Ma Z, et al. Three dimensional optical angiography. Optics Express. 2007;15:4083–4097. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.004083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tao YK, Davis AM, Izatt JA. Single-pass volumetric bidirectional blood flow imaging spectral domain optical coherence tomography using a modified Hilbert transform. Optics Express. 2008;16:12350–12361. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.012350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu G, Jia W, Sun V, et al. High-resolution imaging of microvasculature in human skin in-vivo with optical coherence tomography. Optics Express. 2012 doi: 10.1364/OE.20.007694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.An L, Qin J, Wang RK. Ultrahigh sensitive optical microangiography for in vivo imaging of microcirculations within human skin tissue beds. Optics Express. 2010;18:8220–8228. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.008220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.An L, Wang RK. In vivo volumetric imaging of vascular perfusion within human retina and choroids with optical micro-angiography. Optics Express. 2008;16:11438–11452. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.011438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Atry F, Frye S, Richner TJ, et al. Monitoring cerebral hemodynamics following optogenetic stimulation via optical coherence tomography. Biomedical Engineering, IEEE Transactions on. 2015;62:766–773. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2364816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Faber DJ, Mik EG, Aalders MCG, et al. Toward assessment of blood oxygen saturation by spectroscopic optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2005;30:1015–1017. doi: 10.1364/ol.30.001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lu CW, Lee CK, Tsai MT, et al. Measurement of the hemoglobin oxygen saturation level with spectroscopic spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2008 doi: 10.1364/ol.33.000416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xuan L, Kang JU. Depth-resolved blood oxygen saturation assessment using spectroscopic common-path Fourier domain optical coherence tomography. Biomedical Engineering, IEEE Transactions on. 2010;57:2572–2575. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2010.2058109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Robles FE, Wilson C, Grant G, et al. Molecular imaging true-colour spectroscopic optical coherence tomography. Nature Photonics. 2011;5:744–747. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2011.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Faber DJ, G Mik E, G Aalders MC, et al. Light absorption of (oxy-)hemoglobin assessed by spectroscopic optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2003;28:1436–1438. doi: 10.1364/ol.28.001436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jacques SL. Optical properties of biological tissues: a review. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2013;58:R37–R61. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/11/R37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Aguirre AD, Chen Y, G Fujimoto J, et al. Depth-resolved imaging of functional activation in the rat cerebral cortex using optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2006;31:3459–3461. doi: 10.1364/ol.31.003459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Srinivasan VJ, Sakadžić S, Gorczynska I, et al. Depth-resolved microscopy of cortical hemodynamics with optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2009;34:3086–3088. doi: 10.1364/OL.34.003086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rajagopalan UM, Tanifuji M. Functional optical coherence tomography reveals localized layer-specific activations in cat primary visual cortex in vivo. Optics Letters. 2007;32:2614–2616. doi: 10.1364/ol.32.002614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen Y, Aguirre AD, Ruvinskaya L, et al. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) reveals depth-resolved dynamics during functional brain activation. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2009;178:162–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Maheswari RU, Takaoka H, Kadono H, et al. Novel functional imaging technique from brain surface with optical coherence tomography enabling visualization of depth resolved functional structure in vivo. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2003 Mar 30;124:83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00370-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Graf BW, Ralston TS, Ko HJ, et al. Detecting intrinsic scattering changes correlated to neuron action potentials using optical coherence imaging. Optics Express. 2009;17:13447–13457. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.013447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Akkin T, Joo C, de Boer JF. Depth-resolved measurement of transient structural changes during action potential propagation. Biophysical Journal. 2007;93:1347–1353. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.091298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]