Abstract

Background

The use of communication technologies is an emerging trend in healthcare and research. Despite efficient, reliable and accurate neuropsychological batteries to evaluate cognitive performance in-person, more diverse and less expensive and time consuming solutions are needed. Here we conducted a pilot study to determine the applicability of a videoconference (VC, Skype®) approach to assess cognitive function in older adults, using The Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status-Modified – Portuguese version (TICSM-PT).

Methods

After inclusion and exclusion criteria, 69 individuals (mean age = 74.90 ± 9.46 years), selected from registries of local health centers and assisted-living facilities, were assessed on cognitive performance using videoconference, telephone and in-person approaches.

Findings

The videoconference administration method yielded comparable results to the traditional application. Correlation analyses showed high associations between the testing modalities: TICSM-PT VC and TICSM-PT telephone (r = 0.885), TICSM-PT VC and MMSE face-to-face (r = 0.801). Using the previously validated threshold for cognitive impairment on the TICSM-PT telephone, TICSM-PT VC administration presented a sensitivity of 87.8% and a specificity of 84.6%.

Interpretation

Findings indicate for the range of settings where videoconference approaches can be used, and for their applicability and acceptability, providing an alternative to current cognitive assessment methods. Continued validation studies and adaptation of neuropsychological instruments is warranted.

Keywords: Cognitive instruments, Telemedicine, Epidemiological studies, Ageing

Highlights

-

•

The progress of proper and innovative methods to screen and monitor cognitive function is essential.

-

•

TICSM(-PT) via videoconference had high correlations with other methods and presented good sensitivity and specificity.

-

•

Computer-based cognitive assessment may provide an impetus for epidemiological research and clinical care.

The work reports and compares the use of new technologies, namely videoconference, in the non-presential cognitive assessment of an older population, both healthy and with early Alzheimer's Disease, from the community, day care centers and nursing homes. A very strong association was found between the results of the test applied by telephone, face-to-face and, the novelty of the work, by videoconference, validating and potentiating the use of remote technologies. The expected associations between the scores in the different test administration methods, and the different groups in regard to education, health status and age, were also found.

1. Introduction

Demographic ageing is a worldwide phenomenon that presents new socio-economic and health challenges, with an increasing need for proficient healthcare services to meet the needs of older adults. Most relevant, ageing is accompanied by cognitive decline; (Ciemins et al., 2009) thus, an efficient assessment process to determine cognitive status in aged individuals is of uttermost need. However, a comprehensive neuropsychological testing is a lengthy ordeal that goes well beyond several hours of physical presence in a healthcare institution.

With the broad availability and diffusion of the Internet, computer-based cognitive assessment can provide the greatly needed renewed impetus on cognitive function assessment (Wild et al., 2008). In fact, videoconferencing (VC) has been used to carry out clinical consultations of older people (Hildebrand et al., 2004). Such approach minimizes, for example, the burden of travel for seniors who live in remote/rural areas (Shores et al., 2004). Regarding cognitive testing it can also be a cost-saving methodology and may be suited for broad screening strategies (Wild et al., 2008, Castanho et al., 2015). In fact, good agreement between face-to-face versus non face-to-face methodology has been reported (Timpano et al., 2013, Weiner et al., 2011). For example, Hildebrand and colleagues (Hildebrand et al., 2004) administered via in-person and by videoconference a battery of neuropsychological tests to 29 cognitively intact older adults; multiple cognitive measures demonstrated high degree of concordance between the two methods of evaluation. A feasibility study in older subjects with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease (AD) found correlations between 0.5 and 0.8 on a brief battery of neuropsychological instruments administered in-person and via videoconference (Cullum et al., 2006). There are also some studies on the use of videoconference to diagnose and treat cognitive disorders in the elderly, such as brain injury and other neurological disorders (Shores et al., 2004, Lott et al., 2006). In fact, work has demonstrated good correlations between various cognitive tests using other technologies compared with face-to-face interview, most often using telephone-based instruments (Castanho et al., 2015). Among these, the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS; original instrument) (Brandt et al., 1988) is the most commonly used tool used by telephone for screening of cognitive status in older/elderly individuals. Still, the establishment of a practical assessment of cognition through videoconference is unexplored. On this, the most practical solution could be the addition of video to validated telephone instruments, allowing to create a social presence and bypass problems posed by telephone methods (Menon et al., 2001, Castanho et al., 2015).

Here, addressing this need, the purpose was to use a videoconference approach of the TICSM in different settings: (i) full-time community-dwellers, (ii) those resorting to assisted-living during the daytime (day care centers), and (iii) full-time residents in nursing homes with diagnosed Alzheimer's Disease. To our knowledge, there are no studies that compare three separate administration methodologies of cognitive screening in the same individual and across different settings/groups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

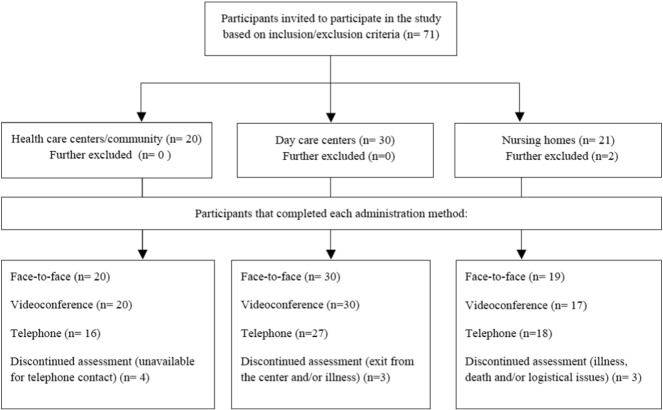

A convenience sample was selected from Braga and Paços de Ferreira (Portugal) local health centers, assisted-living day-care centers and nursing homes. After inclusion/exclusion criteria, the final sample was composed of 69 subjects (40.6% men), with ages between 57 and 95 years (mean = 74.33, SD = 9.46). Formal education level ranged between 0 and 17 years. All participants from the local health centers (n = 20) were community-dwellers and all participants from the day care centers (n = 30) attended the center on a partial basis (afternoon and/or morning period, night time at family residence). The remaining participants (n = 19) were residents in a licensed skilled nursing facility with 24-hours care. The sample characterization is summarized in Table 1 and the participant flow chart in Fig. 1. Portuguese citizens are registered in local health centers since birth and are automatically assigned a family/general practitioner. Individuals requesting assisted-living support (partial or full-time) are allocated to their local centers. On measures of literacy, (un)employment rates, positive experience/mental health, and other socio-demographic characteristics, Portugal ranks close to the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; www.oecd.org/) average.

Table 1.

Sample characterization.

| Gender | |

| Male | 28 (40.6%)a |

| Female | 41 (59.4%)a |

| Age | 74.3 (9.46), [57–95]b |

| Years of formal education | 4 (3.29), [0–17] b |

| Group | |

| Healthy | 50 (72.5%)a |

| AD | 9 (27.5%)a |

| Provenience/setting | |

| Community | 20 (29.0%)a |

| Day care center | 30 (43.5%)a |

| Nursing home | 19 (27.5%)a |

Data presented as n (% of total sample).

Data presented as mean (SD), [range].

Fig. 1.

Participants flow diagram.

The primary exclusion criteria included inability to understand informed consent, choice to not participate or withdraw from the study, incapacity and/or inability to perform or complete each of the cognitive screening assessment sessions. Nursing home residents were previously diagnosed with early Alzheimer's disease by the psychologist of the institution or by a psychiatrist. Clinical information for all participants was obtained from medical records and through neuropsychological evaluations and/or neuroimaging exams.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (59th Amendment) and approval was obtained from the national and local ethics committees. Written informed consent was obtained from all volunteer participants prior to participation and recording of the evaluations. Because patients with Alzheimer's disease may be impaired in their ability to give adequate informed consent, which may be the case even in the disease's earliest, their primary caregiver and/or surrogate decision maker also signed the informed consent.

2.2. Procedure

The testing set-up included two laptops, one running Microsoft® Windows 7® (i5 M450, 2.40 GHz, 4GB RAM) for participants' use, and a second running Microsoft® Windows 7® (Intel Pentium® B950, 2.1Ghz, 6GB RAM) for the psychologist's use. Both laptops had built-in microphones and web cameras. The TICSM administration took place through real-time videoconference carried out with the free video-call software Skype® v6.16 on both computers. Audio, video and connection settings were adjusted in each evaluation session in order to achieve good quality of communication.

At the start of the videoconference evaluation, the psychologist gave each participant a brief introduction regarding the VC-Skype® testing procedure and explained that would only appear on a screen but that another psychologist would be readily available in person if necessary. For all assessments, the psychologist in the room was out of the participant's line of sight, and primarily assessed for the testing conditions and took note of any difficulty or (internet) connection problem. Otherwise could not intervene. For safety concerns, and well care of the study participants/patients, in the day care centers and nursing homes there was always a health professional of the institution outside the closed door. Among the individuals diagnosed with early Alzheimer's disease this is an established safety measure in order to prevent patients from leaving the room unattended. For the full-time community-dwellers testing took place at the Clinical Academic Center-Braga (2CA, Braga, Portugal); for all other participants testing took place at an adequate room of the day care center or nursing home. Each evaluation by telephone took 7 to 8 min, and by videoconference took on average 2 min longer to administer when also accounting for computer/video connection setup time. No confusion regarding who was at the other end of the telephone and videoconferencing was noted throughout the assessment for any of the participants.

To indicate for the acceptability, anxiety and ease of the participants, an informal guided discussion was previously held in a small group, for individuals of each of the settings (community, day care center and nursing home). Feedback on the quality of connection (sound and image) in order to particularly address for potential difficulties for those with hearing or visual impairment was obtained. The pilot sample was not considered/included in the study, but a similar informal discussion, which addressed the same parameters, also followed each videoconference assessment for the study participants (Table 6).

Table 6.

Feedback from individuals concerning TICSM-PT VC assessment.

| N of participants who took part in the discussion | % of total sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal communication | Ease in communication between psychologist and participant | 52 | 75 |

| Being anxious or nervous during examination | 2 | 2.8 | |

| Ease in understanding test instructions during VC assessment | 58 | 84 | |

| Satisfaction with the equipment | Comfort with the equipment used | 61 | 88 |

| Poor audio or visual quality | 8 | 11.5 | |

| Ease in manipulating the computer | 10 | 14.5 | |

VC = Videoconference.

2.3. Instruments

Originally developed from the MMSE, the TICSM has a high validity and reliability on the screening of cognitive impairment (Welsh et al., 1993). Summarily, it consists of 13 items that assess different domains of cognitive function (orientation, learning, attention/calculation, language and delayed recall) (Castanho et al., 2014). The instrument has been validated in the Portuguese (PT) population (TICSM-PT) (Castanho et al., 2015) showing satisfactory internal consistency and convergent and divergent validity.

All participants went through the assessments in the same order: face-to-face, videoconference and telephone. The TICSM-PT via videoconference was applied 1 month after the MMSE face-to-face assessment; thereafter, after a 2-month interval from the videoconference administration, the TICSM-PT was applied by telephone. This allowed avoiding any learning effect (Mitsis et al., 2010). The MMSE (“gold standard”, face-to-face administration) (Folstein et al., 1975) takes approximately 5 to 10 min to administer and has a maximum possible score of 30 points. The same psychologist conducted all assessments. Permission was obtained from the Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. (PAR, Inc.) for the use of the TICS with a delayed recall item (TICSM) (Castanho et al., 2015).

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard error of the mean and range) were obtained for the socio-demographic and cognitive variables: gender, age, education, MMSE and TICSM-PT domains. The characteristics of the distribution of the data were analyzed with Skewness (Sk) and Kurtosis (K) values. Independent sample t-tests were calculated to compare the TICSM-PT and the MMSE scores between genders, level of education and age groups (young old: individuals < 75 years; oldest old: individuals with 76 years and higher). A similar analytical procedure was used to compare healthy individuals and early Alzheimer's disease patients. Furthermore, these scores were also compared between settings (community and day care centers) for the healthy subsample/group.

Linear regression analyses were conducted to determine the most relevant predictors (age, education, gender and healthy or Alzheimer's disease group) of the results of the different administration methods. Confidence intervals (95% level) were calculated for each independent variable. Covariance matrix and R squared change statistics were obtained. Correlation analyses were conducted to assess the magnitude of association between administration procedures of the TICSM-PT and the MMSE, and other variables. Furthermore, measures of association were also obtained between the same domains assessed through different administration forms of the TICSM-PT, as a strategy to comprehensively explore the similarities between the results of videoconference and telephone. A receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis was conducted to evaluate the discriminative ability of the TICSM-PT VC to distinguish between normal and cognitively impaired individuals. For this purpose, the TICSM-PT telephone total score with a cutoff of 13.5 was used as the test variable. This follows the threshold recently validated in a previous paper of our group (Castanho et al., 2015). P-values equal or < 0.05 were considered to be significant. SPSS v23 (IBM SPSS Statistics) was used to perform all descriptive and statistical analyses.

3. Results

The descriptive statistics for the TICSM-PT (videoconference and telephone) and the MMSE (in person) are presented on Table 2 (Mean ± SE). The TICSM-PT (both administration methodologies) and the MMSE scores presented acceptable Sk (range: − 1.34 to − 0.01) and K values (range: − 0.66 to 0.16). There were no significant differences between male and female individuals in any of the tests. The older individuals exhibited significantly lower performance, and individuals with higher education levels presented significantly higher scores. Alzheimer's disease patients had decreased performance in all tests. Community dwellers had higher scores on both administration forms of the TICSM-PT.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for TICSM-PT (videoconference and telephone) and MMSE (face-to-face) total scores.

| TICSM-PT VCa |

TICSM-PT Telephonea |

MMSEa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | N | Mean (SE) | N | Mean (SE) | N | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 15.5 (1.09) | 27 | 14.6 (1.17) | 25 | 24.1 (0.96) | 28 |

| Female | 12.9 (0.95) | 40 | 13.6 (1.19) | 36 | 23.9 (0.94) | 41 |

| t(df), p | t (65) = 1.8, p = 0.075 | t (59) = 0.6, p = 0.575 | t (67) = 0.1, p = 0.883 | |||

| Age | ||||||

| Young old | 17.3 (0.83) | 35 | 17.1 (1.08) | 31 | 26.0 (0.71) | 36 |

| Oldest-old | 10.3 (0.85) | 32 | 10.7 (1.03) | 30 | 21.9 (1.07) | 33 |

| t(df), p | t (65) = 5.8, p = 0.001 | t (59) = 4.3, p ≤ 0.001 | t (67) = 3.3, p ≤ 0.001 | |||

| Education | ||||||

| Lower | 11.2 (0.90) | 28 | 11.5 (1.2) | 26 | 22.6 (1.08) | 29 |

| Higher | 15.9 (0.97) | 39 | 15.8 (1.06) | 35 | 25.0 (0.84) | 40 |

| t(df), p | t (65) = − 3.4, p = 0.001 | t (59) = − 2.6, p = 0.012 | t (67) = − 1.8, p = 0.070 | |||

| Group | ||||||

| Healthy | 15.9 (0.69) | 50 | 16.4 (0.86) | 43 | 26.2 (0.50) | 50 |

| AD | 8.1 (5.12) | 17 | 8.1 (1.14) | 18 | 18.1 (1.35) | 19 |

| t(df), p | t (65) = 5.6, p ≤ 0.001 | t (59) = − 5.4 , p ≤ 0.001 | t (67) = − 7.0, p ≤ 0.001 | |||

| Provenience/settingb | ||||||

| Community | 18.8 (1.12) | 20 | 19.7 (1.41) | 16 | 27.2 (0.57) | 20 |

| Day care center | 14.0 (0.69) | 30 | 14.5 (0.93) | 27 | 25.6 (0.73) | 30 |

| t(df), p | t (48) = 3.8, p ≤ 0.001 | t (41) = 3.2, p = 0.003 | t (48) = 1.5, p = 0.129 | |||

TICSM-PT = Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status Modified–Portuguese–Portuguese; MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination; AD = Alzheimer's disease.

After exclusion/inclusion criteria of the n = 69 recruited individuals, n = 8 were not able to participate in the telephone assessment due to changes in contact information, health problems, death or persistent difficulties to be reached within the time frame. The videoconference evaluation was stopped for one AD participant due to major difficulties in focusing attention and because the patient was unable to respond to the instrument questions.

Non-AD participants.

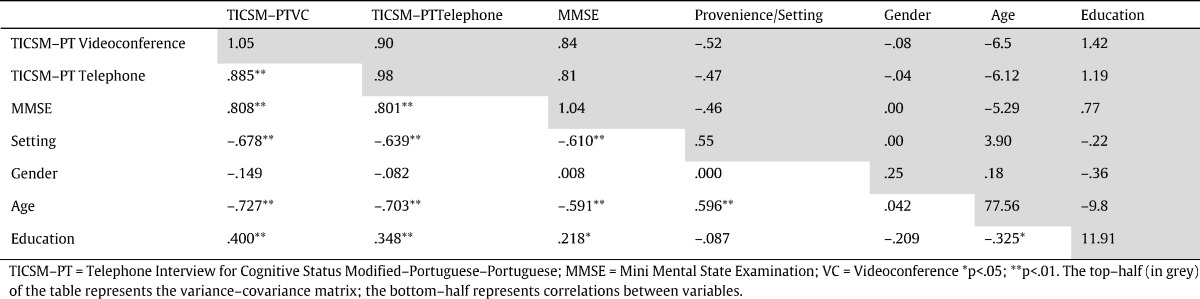

The analysis of the correlation matrix revealed that the different administration procedures presented positive and significant correlations between each other (Table 3). There was a significant association between performance on the TICSM-PT VC and the TICSM-PT telephone scores (r = 0.885, p < 0.001), the TICSM-PT VC and the MMSE (r = 0.801, p < 0.001), and the TICSM-PT telephone and the MMSE (r = 0.808, p < 0.001). As expected, age and education revealed to be significantly associated with each method. Setting showed a significant association with both administration methods of the TICSM-PT and with the MMSE. The magnitude and significance of these effects and the variance-covariance matrix are also presented in Table 3. Linear regression analyses indicated that the socio-demographic variables (gender, age, education and group) significantly predict scores in the distinct administration procedures, explaining 47.5% (R2adj = 0.475), 59.2% (R2adj = 0.592) and 45.6% (R2adj = 0.456) of the total variance of the TICSM-PT VC, TICSM-PT telephone and MMSE, respectively. On this, group was the most relevant contributor to these models, being a significant (positive) predictor in each of the different administration procedures. Education level was a significant predictor of total score on the TICSM-PT via videoconference. The coefficients of individual variables in each model are presented in Table 4. The magnitude of correlation between the same domains, assessed through different modalities, revealed moderate to strong effects (range: 0.495 to 0.866), suggesting good convergent validity of TICSM-PT assessed through videoconference (Table 5).

Table 3.

Correlations and variance-covariance matrix between administration methods and socio-demographic variables.

TICSM-PT = Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status Modified–Portuguese–Portuguese; MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination; VC = Videoconference.

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. The top-half (in grey) of the table represents the variance-covariance matrix; the bottom-half represents correlations between variables.

Table 4.

Prediction of TICSM-PT (videoconference and telephone) and MMSE scores based on socio-demographic characteristics.

| B | SE | Beta | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TICSM-PT videoconference | (Constant) | 17.2 | 2.62 | 6.56 | 0.000 | |

| Gender | –1.64 | 1.01 | –0.136 | –1.62 | 0.111 | |

| Age | –4.69 | 0.99 | –0.396 | –4.73 | 0.000 | |

| Education | 2.761 | 1.02 | 0.230 | 2.71 | 0.009 | |

| Group | 6.32 | 1.12 | 0.464 | 5.65 | 0.000 | |

| F(4,62) = 25.04, p < 0.001; R2 = 0.617; R2adj = 0.592 | ||||||

| TICSM-PT telephone | (Constant) | 14.99 | 3.34 | 4.48 | 0.000 | |

| Gender | –0.58 | 1.33 | –0.043 | –0.43 | 0.667 | |

| Age | –4.6 | 1.29 | –0.332 | –3.38 | 0.001 | |

| Education | 2.51 | 1.34 | 0.189 | 1.88 | 0.066 | |

| Group | 7.06 | 1.43 | 0.491 | 5.03 | 0.000 | |

| F(4,56) = 14.6, p < 0.001; R2 = 0.510; R2adj = 0.475 | ||||||

| MMSE | (Constant) | 20.89 | 2.77 | 7.53 | 0.000 | |

| Gender | 0.06 | 1.09 | 0.005 | 0.06 | 0.955 | |

| Age | –2.18 | 1.07 | –0.196 | –2.05 | 0.045 | |

| Education | 1.51 | 1.10 | 0.134 | 1.38 | 0.174 | |

| Group | 7.38 | 1.16 | 0.592 | 6.34 | 0.000 | |

| F(4,64) = 15.3, p < 0.001; R2 = 0.477; R2adj = 0.456 | ||||||

TICSM-PT = Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status Modified–Portuguese–Portuguese; MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination; VC = Videoconference.

Table 5.

Correlations and covariance matrix of TICSM-PT domains between videoconference and telephone administration.

| TICSM-PT videoconference | TICSM-PT telephone |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orientation | Registration | Attention | calculation | Comprehension | Language repetition | Delayed recall | ||

| Orientation | r | 0.866a | |||||

| Covariance | 0.902 | ||||||

| Registration | r | 0.668a | |||||

| Covariance | 0.685 | ||||||

| Attention | calculation | r | 0.851a | |||||

| Covariance | 0.858 | ||||||

| Comprehension | r | 0.670a | |||||

| Covariance | 0.673 | ||||||

| Language repetition | r | 0.605a | |||||

| Covariance | 0.599 | ||||||

| Delayed recall | r | 0.495a | |||||

| Covariance | 0.498 | ||||||

| M ± SE TC | 5.4 ± 0.23 | 2.1 ± 0.17 | 3.1 ± 0.29 | 1.6 ± 0.13 | 0.8 ± 0.05 | 0.9 ± 0.15 | |

| M ± SE telephone | 4.9 ± 0.27 | 2.4 ± 0.20 | 2.8 ± 0.27 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.05 | 1.2 ± 0.17 | |

| Paired t-test | t(58) = 4.0, p < 0.001 | t(58) = − 2.1, p = 0.038 | t(58) = 1.8, p = 0.081 | t(58) = − 4.1, p < 0.001 | t(58) = − 1.1, p = 0.260 | t(58) = − 1.92,p = 0.060 | |

TICSM-PT = Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status Modified–Portuguese–Portuguese.

p < 0.01.

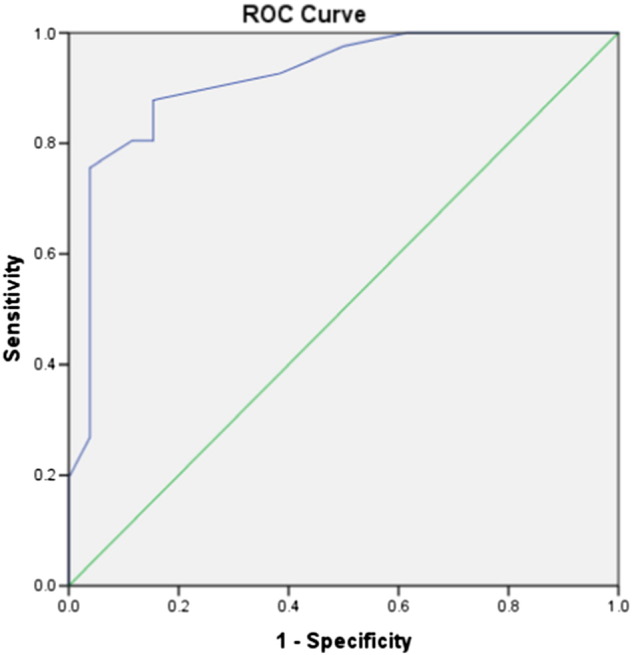

The area under the curve (AUC) statistic (Fig. 2), obtained from the receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis, was 91.7% (95% confidence intervals: 84.5–98.8%). This result evidences the high level of accuracy for cognitive impairment and outstanding discriminative power of TICSM-PT VC. The calculated optimal TICSM-PT VC cutoff score for cognitive impairment was 11.5. Using this threshold, the sensitivity and specificity are 87.8% and 84.6%, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis of the TICSM-PT Videoconference. The area under the curve (AUC) statistic is 91.7% (95% confidence intervals: 84.5–98.8%).

An informal discussion followed each VC assessment. Feedback concerning the videoconference testing modality is presented in Table 6. None of the participants requested to “not be evaluated again” and all showed interest in potential follow-up studies using the same methodology. All individuals who reported that had previously ‘chatted (online)’ using a computer (14.5%), indicated being “fully at ease” throughout the videoconference test administration. Most participants did not indicate any preference between the videoconference and the telephone approach, if a computer was to be available, but most indicated that “enjoyed seeing the evaluator face-to-face”. Only 3% of participants admitted that they “felt anxious/nervous” during the videoconference evaluation, but were able to resume after a brief reassurance by the test administrator/psychologist. Eighty-four percent reported that testing instructions were “easy to understand” and 75% found it “easier to communicate” with the psychologist during videoconference evaluation compared to telephone. Despite feeling comfortable with the equipment (88.0%), 11.5% of participants indicated that videoconference had poor sound and visual quality.

4. Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that cognitive assessment conducted via videoconference, using the TICSM(-PT) as the base instrument, is a valid and useful method. A strong association was found between the TICSM-PT applied by videoconference and by telephone, and between these and the MMSE face-to-face, encouraging the use of the approach as reliable. Across the TICSM-PT domains, correlations were considered from adequate to good evidence of convergent validity between the two approaches (videoconference and telephone). As expected, socio-demographic characteristics, such as age and education, affected the TICSM-PT total score (decrease), both when applied by videoconference and by telephone, which is expected due to the age-related cognitive decline. Using the ROC curve, TICSM-PT VC showed a high accuracy for cognitive impairment discrimination, albeit the optimal cutoff of the TICSM-PT VC for dementia in this study being lower than the one reported in the previous TICSM-PT by telephone validation study of our group (Castanho et al., 2015). The cutoff score may be influenced by the inner characteristics of the study population, which was here comprised by a more heterogeneous sample. The findings indicate that a videoconference approach may be, at least as valid as the telephone method of administration, suggesting that cognitive assessments of individuals with suspected or diagnosed dementia using videoconference merits further development and may significantly aid in diagnosis and/or patient follow-up.

The potential uses of technology in providing access to care are wide, including in older populations (Ball and Puffett, 1998) as here addressed. In fact, overall, eHealth is becoming an everyday term and is, to various degrees, permeating the lives of many. For instance, in a recent study, Salisbury et al. (2016) conducted a trial test of the effectiveness of integrating a (multicomponent) telehealth intervention into general practice for the treatment and management of depression. The need of telemedicine is, however, not confined to mental disease. In cognitive assessment it can be of use as a pre-step, or as a follow-up, to more in-depth/in-office consultations. The allying of technology and neuropsychological assessment, for those in multiple contexts, should become a readily available reality and it requires continued studies. For example, in older adults, the intra- and inter-individual heterogeneity in cognitive ageing, and the need to reach diverse populations, challenges the adaptability of the available instruments currently used to assess and/or screen for (in general) cognitive status. More so, older people represent a significant portion of the population in remote areas, where specialized care is a challenge (Ramos-Rios et al., 2012). More so, with advancing years, many individuals, due to functional, health or other limitations, make the transition from community dwelling to partial- or full-time care to assisted-living facilities. Thus, health services via technologies can provide to those in need substantial monitoring/support (Tyrrell et al., 2001), across health groups and residential settings.

Further highlighting the promising uses of the technology, videoconference has been used in clinical areas of patient diagnosis/assessment. For instance, Ciemins and colleagues examined the reliability of the MMSE administration via remote administration in a sample of 72 patients with diabetes (Ciemins et al., 2009). Findings revealed that 80% of individual test items demonstrated an agreement of ≥ 95% between ‘remote’ to ‘face-to-face’ methods. Barton et al. described a videoconference neuropsychological assessment in a clinical setting (Barton et al., 2011). Using videoconference, a comprehensive battery of tests comprising clinical and neurologic assessments was performed in 15 veterans. Results indicated that videoconference is a feasible method to provide consultation and care to people who could otherwise not have access to it. It was also possible to reach a working diagnosis and recommend relevant treatments for each patient. A more recent study investigated the feasibility of administering a measure of global cognitive function, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test, face-to-face and then remotely via videoconference in 11 participants with Parkinson's disease (Stillerova et al., 2016). The authors reported that the higher scores in the test were not favored by either method of administration (i.e. videoconference via Skype or face-to-face) and concluded that videoconference evaluation may be a viable option to screen for cognition in patients with the disease.

The use of the technology may expand to randomized clinical trials. When managing clinical trials two of the most significant challenges are recruiting the right participants and retaining them for the duration of the trial. Burden of travel, and time and distance from the study site, may render it difficult to recruit participants. This can contribute to dropout rates, potentially causing long delays and increasing the risk of the study to fail. Videoconference may provide solutions in order to overcome these limitations in studies of this nature. De Las Cuevas et al. (2006) carried out a randomized clinical trial with 140 psychiatric patients that were randomized to receive treatment either face-to-face or via videoconference. Results indicated that treatment via the latter had equivalent efficacy to the in-person conventional treatment (De Las Cuevas et al., 2006). Additionally, Dorsey and colleagues evaluated in a randomized clinical trial the feasibility, effectiveness and economic benefits of videoconference care for 20 individuals with Parkinson disease in their home (Dorsey et al., 2013). They reported that videoconference offered similar clinical control, and saved participants 100 miles of traveling and 3 h of time.

In this background, it can be foreseen that individuals could do a diagnostic neuropsychological evaluation via the use of a videoconference approach. However, a few considerations and challenges on the use of technology must be addressed. Foremost, the privacy, security and confidentiality of (free) videoconferencing software must always be taken into account; each country's ethical/security standards must be followed. More so, women, older and less educated individuals may be less receptive to technology. For example, Kerschner and Hart (Zimmer and Chappell, 1999, Tun and Lachman, 2010) indicated that men, younger individuals, and those with higher education, are more receptive and report less anxiety. The link found between education and technology acceptability is of consideration. Studies have revealed that higher levels of education are associated to higher levels of both computer knowledge and computer interest and lower levels of computer anxiety (Ellis and Allaire, 1999). Here, importantly, the guided-informal discussion (on satisfaction and how difficult and stressful the participants considered the videoconference and telephone evaluations) indicated that the participants' acceptability of videoconference administration was satisfactory and on par with the acceptability of the telephone assessment. This is critical because the VC administration has several advantages, including the possibility to capture the participants' non-verbal cues, such as facial expressions and attentiveness, as well as to detect for the use of external cues/test aids. This helps not only the interviewer-participant communication, but also the overall assessment. Also, when applying videoconference (and telephone) methodologies surrounding distractions are of concern (e.g. ambient noises that make harder to hear/follow the instructions and test questions). These can potentiate sensory deficits, which can decrease the capacity to interact over a videoconference/telephone connection. Individuals with impairment can have difficulties in maintaining and sustaining attention. We speculate that in the present study the participants (particularly those with impairment) were able to maintain attention due to the brevity of the telephone/videoconference evaluation. Moreover, health professionals should primarily focus on the development of a therapeutic relationship and on patients' motivation. A recommendation is to start the evaluations with a brief conversation, or with a few questions that should not invalidate or conflict with the questions of the instrument, but would put the participant more at ease. In the present study, in some occasions, some instructions or questions had to be repeated. It could not be easily determined if because these could not be understood due to audio problems or because the participant could not, in fact, “cognitively” comprehend the question. Thus, instruments should be adapted or developed to include two or three “easy to answer” non-interfering questions, dispersed throughout the assessment, so to internally assess and/or control for this. Finally, it would be of great relevance the design/development and validation of an instrument that could be used in all settings here considered (in-person and non in-person) across ageing groups.

In sum, used with care and due considerations, technology can be used to improve the capacity to reach a great number of individuals, located at multiple stations, in a short period of time, offering timely responses, avoiding time and money loss due to travel and time missed at work, and aiding in clinical studies and epidemiological data collection. Beyond its use to carry out cognitive assessments, improving the assistance to (older) individuals, with cognitive impairment or not (and still professionally active or not), it can be speculated to help in the management of clinical conditions. Videoconference can be effective in direct patient interventions and psychotherapy in providing, for instance, greater continuity of care and access to isolated individuals. It can also potentially allow to enhance the structure of an intervention program, the possibility of relapse prevention and the exchange of nonverbal communication between the therapist and patient.

Currently, a limitation of computerized cognitive testing in older people is the lack of psychometric data (for example, normative, reliability and validity data) compared with traditional “paper and pencil” measures (Fazeli et al., 2013). Available studies are limited because of the small sample sizes used and with cohorts composed of mainly psychogeriatric inpatients or medical geriatric hospitalized patients. Here, we add to the present body of work, with results supporting the hypothesis of good acceptability of cognitive assessment via a videoconference method, comparable to the traditional face-to-face administration, in both community dwellers and those resorting to partial or full care in care centers. Results from the study are promising and demonstrate the suitability of using eHealth approaches in older individuals and may be a very useful and needed alternative to assess cognitive progression.

Author Contributions

TCC, LA and JM recruited the participants. Cognitive evaluations were performed by TCC. TCC and PSM performed the statistical and data analysis. TCC, LA and NCS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. NCS, NS, JAP and TCC conceived and designed the study. All authors participated in data collection and/or interpretation and contributed substantially to the scientific process leading up to the writing of the submitted manuscript, contributed to its writing and have approved of its final version.

Role of the Funding Source

The funding agencies had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the European Commission (FP7): “SwitchBox” (Contract HEALTH-F2-2010-259772), and co-financed by the Portuguese North Regional Operational Program (ON.2 – O Novo Norte), under the National Strategic Reference Framework (QREN), through the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER), and by the Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian (Portugal) (Contract grant number: P-139977; project “Better mental health during ageing based on temporal prediction of individual brain ageing trajectories (TEMPO)”). TCC and LA are recipients of a doctoral fellowship from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT, Portugal; SFRH/BD/90078/2012 and SFRH/BD/101398/2014, respectively, the latter from the POCH program and co-financed by the Fundo Social Europeu and MCTES); PSM is supported by the FCT fellowship grant (PDE/BDE/113601/2015 from the PhD-iHES program); and, NCS of a Research Assistantship by FCT through the “FCT Investigator Programme (200 ∞ Ciência)”.

References

- Ball C., Puffett A. The assessment of cognitive function in the elderly using videoconferencing. J. Telemed. Telecare. 1998;1:36–38. doi: 10.1258/1357633981931362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton C., Morris R., Rothlind J., Yaffe K. Video-telemedicine in a memory disorders clinic: evaluation and management of rural elders with cognitive impairment. Telemed. J. E Health. 2011;17:789–793. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2011.0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J., Spencer M., Folstein M. The telephone interview for cognitive status. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 1988;1:111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Castanho T.C., Amorim L., Zihl J., Palha J.A., Sousa N., Santos N.C. Telephone-based screening tools for mild cognitive impairment and dementia in aging studies: a review of validated instruments. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014:6. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanho T.C., Portugal-Nunes C., Moreira P.S., Amorim L., Palha J.A., Sousa N., Correia Santos N. Applicability of the telephone interview for cognitive status (modified) in a community sample with low education level: association with an extensive neuropsychological battery. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1002/gps.4301. (n/a-n/a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciemins E.L., Holloway B., Coon P.J., Mcclosky-Armstrong T., Min S.J. Telemedicine and the mini-mental state examination: assessment from a distance. Telemed. J. E Health. 2009;15:476–478. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullum C.M., Weiner M.F., Gehrmann H.R., Hynan L.S. Feasibility of telecognitive assessment in dementia. Assessment. 2006;13:385–390. doi: 10.1177/1073191106289065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Las Cuevas C., Arredondo M.T., Cabrera M.F., Sulzenbacher H., Meise U. Randomized clinical trial of telepsychiatry through videoconference versus face-to-face conventional psychiatric treatment. Telemed. J. E Health. 2006;12:341–350. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.12.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey E., Venkataraman V., Grana M.J. Randomized controlled clinical trial of “virtual house calls” for parkinson disease. JAMA. 2013;70:565–570. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis D., Allaire J.C. Modeling computer interest in older adults: the role of age, education, computer knowledge, and computer anxiety. Hum. Factors. 1999;41:345–355. doi: 10.1518/001872099779610996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazeli P.L., Ross L.A., Vance D.E., Ball K. The relationship between computer experience and computerized cognitive test performance among older adults. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2013;68:337–346. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M.F., Folstein S.E., Mchugh P.R. Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand R., Chow H., Williams C., Nelson M., Wass P. Feasibility of neuropsychological testing of older adults via videoconference: implications for assessing the capacity for independent living. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2004;10:130–134. doi: 10.1258/135763304323070751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lott I.T., Doran E., Walsh D.M., Hill M.A. Telemedicine, dementia and down syndrome: implications for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2006;2:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon A.S., Kondapavalru P., Krishna P., Chrismer J.B., Raskin A., Hebel J.R., Ruskin P.E. Evaluation of a portable low cost videophone system in the assessment of depressive symptoms and cognitive function in elderly medically ill veterans. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2001;189:399–401. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200106000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsis E.M., Jacobs D., Luo X., Andrews H., Andrews K., Sano M. Evaluating cognition in an elderly cohort via telephone assessment. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2010;25:531–539. doi: 10.1002/gps.2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Rios R., Mateos R., Lojo D., Conn D.K., Patterson T. Telepsychogeriatrics: a new horizon in the care of mental health problems in the elderly. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:1708–1724. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury C., O'cathain A., Edwards L., Thomas C., Gaunt D., Hollinghurst S., Nicholl J., Large S., Yardley L., Lewis G., Foster A., Garner K., Horspool K., Man M.S., Rogers A., Pope C., Dixon P., Montgomery A.A. Effectiveness of an integrated telehealth service for patients with depression: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial of a complex intervention. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:515–525. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shores M.M., Ryan-Dykes P., Williams R.M., Mamerto B., Sadak T., Pascualy M., Felker B.L., Zweigle M., Nichol P., Peskind E.R. Identifying undiagnosed dementia in residential care veterans: comparing telemedicine to in-person clinical examination. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2004;19:101–108. doi: 10.1002/gps.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillerova T., Liddle J., Gustafsson L., Lamont R., Silburn P. Could everyday technology improve access to assessments? A pilot study on the feasibility of screening cognition in people with Parkinson's disease using the Montreal cognitive assessment via internet videoconferencing. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2016 doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12288. (n/a-n/a.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpano F., Pirrotta F., Bonanno L., Marino S., Marra A., Bramanti P., Lanzafame P. Videoconference-based mini mental state examination: a validation study. Telemed. J. E Health. 2013;19:931–937. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tun P.A., Lachman M.E. The association between computer use and cognition across adulthood: use it so you won't lose it? Psychol. Aging. 2010;25:560–568. doi: 10.1037/a0019543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrrell J., Couturier P., Montani C., Franco A. Teleconsultation in psychology: the use of videolinks for interviewing and assessing elderly patients. Age Ageing. 2001;30:191–195. doi: 10.1093/ageing/30.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner M.F., Rossetti H.C., Harrah K. Videoconference diagnosis and management of Choctaw Indian dementia patients. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:562–566. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh K.A., Breitner J.C.S., Magruder-Habib K.M. Detection of dementia in the elderly using telephone screening of cognitive status. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 1993;6:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Wild K., Howieson D., Webbe F., Seelye A., Kaye J. Status of computerized cognitive testing in aging: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4:428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer Z., Chappell N.L. Receptivity to new technology among older adults. Disabil. Rehabil. 1999;21:222–230. doi: 10.1080/096382899297648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]