This study provides an updated view using the most recent data to identify the primary storage of clinical data, status of data for meaningful use, and characteristics associated with the implementation of electronic health records in local health departments.

Keywords: electronic health records, information technology control, meaningful use

Background:

Electronic health records (EHRs) are evolving the scope of operations, practices, and outcomes of population health in the United States. Local health departments (LHDs) need adequate health informatics capacities to handle the quantity and quality of population health data.

Purpose:

The purpose of this study was to gain an updated view using the most recent data to identify the primary storage of clinical data, status of data for meaningful use, and characteristics associated with the implementation of EHRs in LHDs.

Methods:

Data were drawn from the 2015 Informatics Capacity and Needs Assessment Survey, which used a stratified random sampling design of LHD populations. Oversampling of larger LHDs was conducted and sampling weights were applied. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and logistic regression in SPSS.

Results:

Forty-two percent of LHDs indicated the use of an EHR system compared with 58% that use a non-EHR system for the storage of primary health data. Seventy-one percent of LHDs had reviewed some or all of the current systems to determine whether they needed to be improved or replaced, whereas only 6% formally conducted a readiness assessment for health information exchange. Twenty-seven percent of the LHDs had conducted informatics training within the past 12 months. LHD characteristics statistically associated with having an EHR system were having state or centralized governance, not having created a strategic plan related to informatics within the past 2 years throughout LHDs, provided informatics training in the past 12 months, and various levels of control over decisions regarding hardware allocation or acquisition, software selection, software support, and information technology budget allocation.

Conclusion:

A focus on EHR implementation in public health is pertinent to examining the impact of public health programming and interventions for the positive change in population health.

Electronic health records (EHRs) are not simply changing how local health departments (LHDs) store patient health information but also evolving the scope of operations, practices, and outcomes of population health. To provide core public health functions of assurance and assessment, LHDs need adequate health information technology (IT) capabilities for the quantity and quality of health data.1,2 EHRs have streamlined processes and shown positive effects on patient care delivery in emergency departments,3 primary care clinics,4 mental health care,5,6 hospitals,7 and nursing homes.8 However, the low numbers of EHR adoption in public health could be limiting the capacity to identify areas of health disparities, measure disease burden, and examine the impact of public health programming and interventions.9

The enactment of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) purposed to increase the adoption and use of health IT in the United States. HITECH provided assistance to eligible providers for adoption, as well as set requirements for meaningful use of EHRs. Most LHDs do not have eligible providers, as they mainly use nurses; therefore, they do not qualify for incentives provided through this program. However, reaching the objectives for meaningful use of EHRs can assist with improvement in quality of care through patient safety,10,11 effectiveness and efficiency, medical error reduction, assistance in decision making,12 and advances in describing appropriateness of care through patient-level measures.13 Societal outcomes mentioned in the literature include abilities to link parent and child records for more comprehensive and holistic care with familial context14 and the availability of clinical data for research and improvement of population health.13

In 2013, the implementation of EHRs was reported successful in 22% of LHDs in the United States.15 In other studies, characteristics of successful EHR implementation included having strong leadership and vision, supportive policies, strategic goal setting and planning, prioritization,16 and communication in the preimplementation phase.17 In addition, having an experienced top executive, larger population size, decentralized governance structure, and a higher per capita expenditure were characteristics of LHDs with successfully implemented EHR systems.18 Standing and Cripps19 indicated that implementation was based on the level of “critical success factors.” These critical success factors included involvement of user or stakeholder, alignment with the vision and strategy, communication and reporting, process for implementation and training, planning for IT infrastructure, and contextual factors such as resources, decision-making authority, accountability, and resistance to adoption.19

Thirty-two percent of LHDs had no activity toward implementing EHRs in 2013.18 Approximately 22% of LHDs are currently offering clinical services.20 Among those LHDs that provide clinical services, many experienced challenges to implementation. The costs of implementation, lack of interoperability, workflow concerns, privacy and security, training and usability, and resistance to change are commonly mentioned barriers in the literature.11,21–25 Low perceived usefulness,26 lack of technical training and support, insufficient financial resources,27 and ethical and legal concerns28 were also highly mentioned challenges to the implementation of EHRs. This research highlights the most recent data, collected in 2015, to identify the storage of clinical data, status of data for meaningful use, and characteristics associated with the implementation of EHRs.

Methods

Data and sampling design

Data were drawn from the 2015 Informatics Capacity and Needs Assessment Survey, conducted by the Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health at Georgia Southern University in collaboration with the National Association of County & City Health Officials (NACCHO). This Web-based survey had a target population of all LHDs in the United States. A representative sample of 650 LHDs was drawn using a stratified random sampling design, based on 7 population strata: less than 25 000; 25 000 to 49 999; 50 000 to 99 999; 100 000 to 249 999; 250 000 to 499 999; 500 000 to 999 999; and 1 000 000 and more. LHDs with larger population were systematically oversampled to ensure the inclusion of a sufficient number of large LHDs in the completed surveys. The targeted respondents were informatics staff designated by the LHDs through a mini-survey conducted prior to the main survey. A structured questionnaire was constructed and pretested with 20 informatics staff members. The questionnaire included various measures to examine the current informatics capacity and needs of LHDs. The survey questionnaire was sent via the Qualtrics survey software to the sample of 650 LHDs. The survey remained open for 8 weeks in 2015. A total of 324 completed responses were received, with a 50% response rate. Given that only a sample of all LHDs participated in the study and the larger LHDs were oversampled and overrepresented, statistical weights were developed to account for 3 factors: (a) disproportionate response rate by population size (7 population strata, typically used in NACCHO surveys), (b) oversampling of LHDs with larger population sizes, and (c) sampling rather than the census approach. This study was approved by the institutional review board at Georgia Southern University in 2015.

Dependent variable

The status of data for meaningful use (stage 1) was assessed by examining the following informatics systems: electronic laboratory reporting, immunization information systems, syndromic surveillance system, cancer registry, and other specialized registries. These systems were categorized by currently receiving, preparing to receive, or not receiving (no system, state-run system, or do not know) data for meaningful use.

Since clinical services are not essential services provided by LHDs, LHDs with no clinical services were not included in this question provided by the 2015 Informatics Capacity and Needs Assessment Survey. The presence of an EHR system was operationalized through the question: “What is your local health department's primary system to contain/organize patient health information (clinical service data) in-house?” The question included the following 7 responses: (1) paper records, (2) basic software, (3) a federally provided system, (4) a custom-built EHR system, (5) a vendor-built EHR system, (6) an open-source EHR system, and (7) electronic record systems other than those listed earlier. Responses 4, 5, and 6 were combined to reflect “EHR system” and responses 1, 2, 3, and 7 were combined to reflect “non-EHR system.” These 2 response categories were included in the logistic regression model.

Independent variable

The independent variables considered for the logistic regression model included LHD characteristics theoretically associated with informatics capacity. Variables included infrastructural and organizational activities, training, and control of IT decisions. Variables regarding infrastructure of LHDs include a 5-level population size (1. <25 000; 2. 25 000-49 999; 3. 50 000-99 999; 4. 100 000-499 999; and 5. ≥500 000) and governance categories (state, local, and shared). The variables representing the organizational activities performed in the past 2 years are reviewed current systems, created a strategic plan for information systems, used formal project management process, formally conducted a readiness assessment, and had the provision of training within the last 12 months. The variables for control of IT decisions were represented by hardware allocation and acquisition, software selection, software support, and IT budget allocation. In addition, the control variables included decisions within each department or program, within LHD (through central department), through city or county IT department, through state agency, or through someone else.

The selection of the variables was made prior to analyses and was based on review of the literature. However, our variable selection was limited by the availability of the 2015 Informatics Capacity and Needs Assessment Survey. The variable selection was also conditioned by elimination of some variables highly correlated with each other. To avoid multicollinearity, we excluded only those independent variables that were not highly correlated with each other. Our final selection of independent variables had the Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.3 or less.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed to compute frequencies and percentages for the meaningful use and independent variables. For modeling the dependent variable dichotomized as “EHR system” versus “non-EHR system,” logistic regression was used. To avoid small cell counts, 2 separate logistic regression models were computed—one to model the organizational characteristics and the other for IT characteristics. The Nagelkerke pseudo-R2 for the first model (Table 1) was 0.77 and for the second model (Table 2) was 0.24. The 95% confidence intervals, descriptive, and regression statistics were calculated using IBM SPSS (version 23).

TABLE 1 •. Logistic Regression Model 1 of LHD Characteristics (Governance, Organizational Activities, and Training) of Having an EHR System Versus Having a Non-EHR System for Primary Health Data Storage.

| LHD Characteristics | n | AOR | Pa | 95% CI for Exp(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Governance category (vs state) | |||||

| Local | 256 | 0.612 | .002 | 0.445 | 0.840 |

| Shared | 38 | 0.577 | .01 | 0.378 | 0.881 |

| Organizational activities in past 2 years (vs no) | |||||

| Reviewed current system | 230 | 0.975 | .82 | 0.786 | 1.210 |

| Created a strategic plan for information systems | 95 | 0.783 | .05 | 0.614 | 0.997 |

| Used formal project management process | 73 | 1.916 | <.001 | 1.483 | 2.476 |

| Formally conducted security risk analysis | 83 | 2.089 | <.001 | 1.653 | 2.642 |

| Formally conducted a readiness assessment | 27 | 0.539 | <.001 | 0.369 | 0.789 |

| Informatics training in past 12 months (vs no) | 92 | 1.866 | <.001 | 1.502 | 2.317 |

| Constant | 0.798 | .16 | |||

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; EHR, electronic health record; LHD, local health department; vs no, reference category is the no response.

aBolded P values express statistically significant LHD characteristics in relation to the implementation of EHRs.

TABLE 2 •. Logistic Regression Model 2 of LHD Characteristics (Control of IT Decisions) of Having an EHR System Versus Having a Non-EHR System for Primary Health Data Storage.

| LHD Characteristics | n | AOR | P | 95% CI for Exp(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Control of IT decisions (vs no)a | |||||

| Hardware allocation or acquisition | |||||

| Within each department or program | 78 | 0.658 | .05 | 0.431 | 1.006 |

| Within LHD (through central department) | 115 | 4.702 | <.001 | 3.042 | 7.268 |

| Through city or county IT department | 141 | 1.950 | .02 | 1.115 | 3.410 |

| Through state agency | 64 | 1.300 | .27 | 0.817 | 2.068 |

| Through someone else | 15 | 9.299 | <.001 | 3.097 | 27.925 |

| Software selection | |||||

| Within each department or program | 114 | 2.875 | <.001 | 1.953 | 4.232 |

| Within LHD (through central department) | 124 | 0.851 | .48 | 0.541 | 1.338 |

| Through city or county IT department | 133 | 3.060 | <.001 | 1.857 | 5.042 |

| Through state agency | 80 | 4.678 | <.001 | 2.869 | 7.628 |

| Through someone else | 19 | 0.272 | .01 | 0.102 | 0.721 |

| Software support | |||||

| Within each department or program | 64 | 0.553 | .01 | 0.364 | 0.841 |

| Within LHD (through central department) | 98 | 2.219 | .004 | 1.290 | 3.815 |

| Through city or county IT department | 156 | 0.622 | .15 | 0.325 | 1.189 |

| Through state agency | 68 | 0.350 | <.001 | 0.219 | 0.559 |

| Through someone else | 35 | 1.290 | .35 | 0.758 | 2.197 |

| IT budget allocation | |||||

| Within each department or program | 127 | 1.174 | .54 | 0.701 | 1.966 |

| Within LHD (through central department) | 97 | 0.457 | .01 | 0.244 | 0.856 |

| Through city or county IT department | 78 | 0.758 | .28 | 0.461 | 1.246 |

| Through state agency | 75 | 1.290 | .32 | 0.780 | 2.132 |

| Through someone else | 22 | 0.040 | <.001 | 0.014 | 0.118 |

| Constant | 0.304 | .001 | |||

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; EHR, electronic health record; IT, information technology; LHD, local health department.

aReference category is no for all variables in this model.

Results

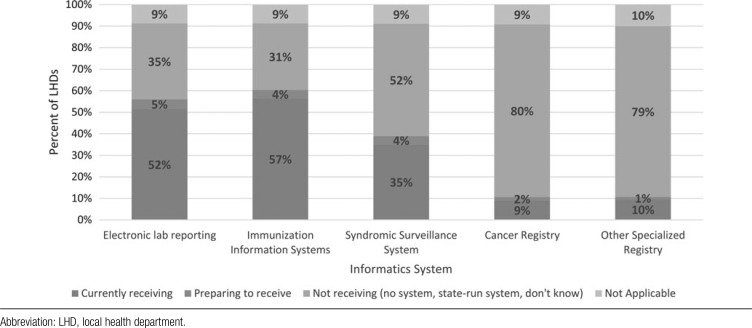

Fifty-seven percent of LHDs are currently receiving data from certified EHRs for meaningful use (stage 1) from immunization information systems, followed by 52% from electronic laboratory reporting, and 35% from syndromic surveillance systems (Figure). Only 9% of LHDs are receiving data from cancer registries, and almost 10% from other specialized registries. More than half of LHDs were not receiving data from certified EHRs for meaningful use from syndromic surveillance systems, cancer registries, and other specialized registries.

FIGURE •.

Status of Receiving Data From a Certified Electronic Health Record for Meaningful Use (Stage 1) by Informatics System.

Forty-two percent of LHDs indicated having an EHR system compared with 58% that use a non-EHR system to store primary health data. Eighty-seven of the 324 LHDs had less than 25 000 population jurisdiction, followed by 79 from 100 000 to 499 999 population size. Approximately 82% of LHDs had local governance compared with almost 10% with shared governance and 9% were state-governed. A majority of the LHD respondents indicated the organization had reviewed some or all of the current systems to determine whether they needed to be improved or replaced (71%), whereas only 6% formally conducted a readiness assessment for health information exchange.

Control of IT decisions regarding hardware allocation and acquisition (43%), software selection (39%), and software support (48%) were indicated most frequently as controlled through city or county IT departments. For IT budget allocation (35%), the control of IT decisions were most often within each department or program. Twenty-seven percent of the LHDs had conducted informatics training within the past 12 months.

After controlling for other independent variables in the model, LHD characteristics statistically associated with having an EHR system were having local governance. The results indicate an inverse relationship between EHR system implementation and having a strategic plan related to informatics in the past 2 years (Table 1). Having a local governance structure was significantly associated with a lowered chance of having an EHR system (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.612, P = .002) than having state governance. LHDs that created a strategic plan for information systems in the past two years were less likely than LHDs that did not create a strategic plan to have EHRs (AOR = 0.783, P = .05). Positive associations existed between LHDs using a formal project management process to implement a new information system (AOR = 1.916, P < .001), formally conducting security risk analysis with regard to public health information systems (AOR = 2.089, P < .001), and formally conducting a readiness assessment for health information exchange (AOR = 0.539, P < .001) and having an EHR system. LHDs that provided informatics training in the past 12 months had twice the odds of using an EHR system compared with those who did not conduct informatics training.

A second logistic regression model was constructed to analyze the association of the control of IT decisions and the presence of EHR systems in LHDs. Table 2 includes the type of IT control and the department, agency, or outside agency that controls it. Characteristics of IT control associated with the presence of an EHR system included hardware allocation or acquisition through someone else (AOR = 9.299, P < .001), within LHD through central department (AOR = 4.702, P < .001). For software selection, a significance positive influence was observed for LHDs with control through state agency (AOR = 4.678, P < .001) or through city or county IT department (AOR = 3.060, P < .001). Software support was significantly associated with having an EHR system when control was through a central department in the LHD (AOR = 2.219, P = .004), within each department or program of the LHD (AOR = 0.553, P = .006), and through the state agency (AOR = 0.350, P < .001).

LHD characteristics statistically associated with having an EHR system were having local governance, not having created a strategic plan for information systems in past 2 years, had informatics training in the past 12 months, and had various agencies and department of controlling IT decision making of hardware allocation or acquisition, software selection, software support, and IT budget allocation.

Discussion

The findings indicate the most commonly received certified EHR data for meaningful use stage 1 was electronic laboratory reporting and immunization information systems. Reaching meaningful use has many implications for LHDs, such as providing real-time and relevant data for patient care, improving in patient health outcomes, and driving action for change in population health.29 Although laboratory reporting and immunization systems are receiving certified EHR data in more than 50% of the LHDs, there is much room for improvement in syndromic surveillance and cancer registry at the local level.

The LHD population size can affect the resources and infrastructure of the LHD, which have an impact on the implementation of EHRs due to the economies of scale and scope.30 Larger LHDs tend to have more resources and control of IT budget allocations and hardware and software acquisition due to a variety of vendors, which causes competition and lower costs. The workforce within the LHD is also affected by increased productivity and a wider range of IT skill sets.31 Governance of the LHD is a factor in EHR implementation. The findings indicate that LHDs with state governance tend to have EHR systems more often than local or shared governance. State health departments have different budget allowances, funding streams, and workforce that greatly influence the capabilities of IT infrastructures.32

Strategic alignment is a key characteristic in the implementation of LHD informatics.19 Regular reviewing and updating of strategic plans can assist with processes surrounding implementation, including communication plans with leaders and employees and action steps for a successful implementation of informatics.19 The presence of a strategic plan regarding informatics in the past 2 years was assessed in this study to determine whether EHR implementation was linked to strategy activities. This study illuminated that the LHDs that have not created a strategic plan for information systems within the past 2 years are more likely to have EHRs. However, since this study did not consider strategic plans created outside of the past 2 years nor the date of EHR implementation, it cannot be conclusively determined that there was an absence of a strategic plan related to informatics just prior to the 2 years.

Our study has some limitations related to biases due to type of respondents and self-reporting of informatics capacities. Before administering the survey that is the source of data for this study, the project team asked the contact persons for the LHDs in the study sample to identify the most relevant informatics staff. Only a quarter of the LHDs provided the informatics staff contacts, resulting in mixed perspective of LHD informatics and the leadership staff. Also, the self-reported survey responses were not independently verified.

Conclusion

Public health agencies, including LHDs, need increased health IT capacities to provide the core public health functions efficiently and effectively.1,2 EHRs are already changing the operations, practices, and outcomes in health care,7 but public health is lagging in adoption.15 Patient safety, error reduction, and advances in population-level health could be achieved through meaningful use of EHRs. As mentioned in the literature, societal outcomes could be the ability to provide holistic and comprehensive care to individuals and populations served by LHDs. This study shows that LHD characteristics that have shown positive influences on implementation of EHRs regardless of population size include reviewing some or all of the current information systems to determine whether they needed to be improved or replaced, conducting formal readiness assessment for health information exchange, providing informatics training, and conducting analysis of control levels of decisions of hardware allocation or acquisition, software selection, software support, and IT budget allocation. A focus on EHR implementation in public health is pertinent for examining impacts of public health programming and interventions for the positive change in population health.9

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Foldy S, Grannis S, Ross D, Smith T. A ride in the time machine: information management capabilities health departments will need. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):1592–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah GH, Luo H, Sotnikov S. Public Health Services Most Commonly Provided by Local Health Departments in the United States. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Assuli O. Electronic health records, adoption, quality of care, legal and privacy issues and their implementation in emergency departments. Health Policy. 2015;119:287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiao Y, Asan O, Montague E. Factors associated with patient trust in electronic health records used in primary care settings. Health Policy Technol. 2015;4:357–363. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strudwic G, Eyasu T. Electronic health record use by nurses in mental health settings: a literature review. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2015;29(4):238–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kadra G, Stewart R, Shetty H, et al. Extracting antipsychotic polypharmacy data from electronic health records: developing and evaluating a novel process. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adler-Milstein J, Everson J, Shoou-Yih DL, Lee S-YD. EHR Adoption and hospital performance: time-related effects. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(6):1751–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramson EL, McGinnis S, Moore J, Kaushal R. A statewide assessment of electronic health record adoption and health information exchange among nursing homes. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(1, pt 2):361–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogel J, Brown JS, Land T, Platt R, Klompas M. MDPHnet: secure, distributed sharing of electronic health record data for public health surveillance, evaluation, and planning. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):2265–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muhammad Zia H, Telang R, Marella WM. Electronic health records and patient safety. Commun ACM. 2015;58(11):30–32. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Key D, Ferneini EM. Focusing on patient safety: the challenge of securely sharing electronic medical records in complex care continuums. Conn Med. 2015;79(8):481–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gan Q. Viewpoint Paper. Is the adoption of electronic health record system “contagious”? Health Policy Technol. 2015;4:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menachemi N, Collum TH. Benefits and drawbacks of electronic health record systems. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2011;4:47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angier H, Gold R, Crawford C, et al. Linkage methods for connecting children with parents in electronic health record and state public health insurance data. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(9):2025–2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Association of County & City Health Officials. 2013 Profile of Local Health Departments. Washington, DC: National Association of County & City Health Officials; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):742–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCullough D. Effective deployment of an electronic health record (EHR) in a rural local health department (LHD). Texas Public Health J. 2013;65(3):14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah GH, Leider JP, Castrucci BC, Williams KS, Luo H. Characteristics of local health departments associated with implementation of electronic health records and other informatics systems. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(2):272–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Standing C, Cripps H. Critical success factors in the implementation of electronic health records: a two-case comparison. Syst Res Behav Sci. 2015;32(1):75–85. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsuan C, Rodriguez HP. The adoption and discontinuation of clinical services by local health departments. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:124–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meigs SL, Solomon M. Electronic health record use a bitter pill for many physicians. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2016;13:1–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hessler BJ, Soper P, Bondy J, Hanes P, Davidson A. Assessing the relationship between health information exchanges and public health agencies. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2009;15(5):416–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirkwood J, Jarris PE. Aligning health informatics across the public health enterprise. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2012;18(3):288–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marsolo K. In Search of a data-in-once, electronic health record-linked, multicenter registry—how far we have come and how far we still have to go. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2013;1(1):1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith PF, Hadler JL, Stanbury M, Rolfs RT, Hopkins RS. “Blueprint version 2.0”: updating public health surveillance for the 21st century. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;19(3):231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamid F, Cline TW. Providers' Acceptance factors and their perceived barriers to electronic health record (EHR) adoption. Online J Nurs Inform. 2013;17(3):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherer SA, Meyerhoefer CD, Peng L. Applying institutional theory to the adoption of electronic health records in the U.S. Inf Manag. 10.1016/j.im.2016.01.002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayatollahi H, Mirani N, Haghani H. Electronic health records: what are the most important barriers? Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2014;11:1–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mushtaq F. Ensuring EHR compliance for meaningful use. Health Manag Technol. 2015;36(7):16–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carey K, Burgess JF, Jr, Young GJ. Economies of scale and scope: the case of specialty hospitals. Contemp Econ Policy. 2015;33(1):104–117. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beitsch LM, Castrucci BC, Dilley A, et al. From patchwork to package: implementing foundational capabilities for state and local health departments. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):e7–e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkin CL, Cerpa N. Strategic information systems planning: an empirical evaluation of its dimensions. J Technol Manag Innov. 2012;7(2):52–61. [Google Scholar]