Summary

Septic cardiomyopathy is commonly encountered in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. This study explores whether novel global and segmental echocardiographic markers of myocardial deformation, using two-dimensional speckle tracking, are associated with adverse sepsis outcomes. We conducted a retrospective observational feasibility study, at a tertiary care centre, of patients admitted to the ICU with a diagnosis of sepsis who underwent an echocardiogram within the first week of sepsis diagnosis. Data were collected on chamber dimensions, systolic and diastolic function, demographics, haemodynamics, and laboratory parameters. Global and segmental left ventricular longitudinal strain (LVLS) and tissue mitral annular displacement (TMAD) were assessed on 12 left ventricular segments and six mitral annulus segments in apical views, respectively. We explored associations of abnormal LVLS and TMAD with duration of mechanical ventilation, hospital length of stay, and mortality. Fifty-four patients were included. Global LVLS was not associated with any of the primary study endpoints. However, reduced systolic LVLS of the basal anterior segment was associated with in-hospital mortality. There was a suggestion that patients with a reduced global TMAD were associated with an increased risk of mortality and a short length of hospital stay but these associations were not statistically significant. Reduced global LVLS was associated with lower ejection fraction. Reduced global TMAD was associated with reduced global and segmental LVLS, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, and increased left ventricular end-systolic and end-diastolic volumes. Speckle-tracking echocardiography can be performed feasibly in patients in sepsis. Global and segmental left ventricular deformation indices are associated with ejection fraction. Further studies need to evaluate the ability of these new indices to predict sepsis outcomes.

Keywords: cardiomyopathy, echocardiography, hospital mortality, sepsis, shock, systole

Sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy (SIC) is a common morbid condition that manifests in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Most of the literature on SIC is derived from single-centre and small observational studies that suffer from conceptual, technical and design flaws. For example, the majority of studies have appraised ventricular function in a global manner using indices such as ejection fraction (EF) and cardiac index, measured via technologically limited tools and at inconsistent timepoints of disease progression, with less of an appraisal of the contribution of myocardial geometry to the mechanical function of the heart1–5. Our group has comprehensively described these limitations in a recently published review6. As a result of these shortcomings, there has not been a consensus on the characterisation of SIC.

In recent years, speckle-tracking echocardiography (STE) technology has evolved as a non-invasive, angle-independent method of appraising the deformation of different layers of myocardial fibres overcoming the limitations of tissue Doppler imaging and of global markers previously used in appraising SIC.

Left ventricular systolic longitudinal strain (LVLS), a measure of the segmental longitudinal deformation of the ventricle, has been shown to be a superior measure of ventricular ischaemia, fibrosis, and hypertrophy, compared to more global indicators of left ventricular (LV) systolic function, such as EF7. In brief, speckle-tracking imaging tracks the unique speckles (known as ‘kernels’) that make up the myocardium, caused by characteristic interferences of ultrasound wave reflection8.

Interestingly, in a recent study in a paediatric population with septic shock, speckle-tracking imaging was shown to detect impaired myocardial performance that was not revealed by EF measurement9. Two recent studies using STE in adults with severe sepsis suggested that LV diastolic dysfunction and right ventricular (RV) systolic dysfunction10 or severe RV free wall longitudinal strain impairment11 were associated with sepsis mortality.

Tissue mitral annular displacement (TMAD), another novel measure quantifiable with speckle-tracking technology to assess the LV longitudinal systolic function by tracking positions across the mitral valve annulus in systole, provides a rapid assessment of LV longitudinal systolic function and does not require high-quality images17. Studies have demonstrated that TMAD may have an important clinical value in early diagnosis, progression and response to therapy in numerous cardiovascular diseases12–14.

Since no prior studies have explored the role of TMAD using speckle-tracking technology in patients with sepsis, the present study aimed to explore the feasibility of, and association between, LVLS and TMAD as measures of longitudinal global and segmental LV systolic function, and outcome in adult patients with sepsis. Our study hypothesis was that reduction in LV global or segmental systolic strain and/or TMAD is associated with any of the following endpoints: hospital mortality, hospital and ICU lengths of stay, and duration of mechanical ventilation in patients with severe sepsis.

Methods

Study population

This observational study was conducted at Harborview Medical Centre, University of Washington, after approval by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board (Application No.: 42540). The study included adult patients admitted to any ICU between 1 January, 2008, and 31 December, 2011, with a diagnosis of sepsis and/or septic shock15 who underwent an echocardiogram within the first week of their ICU stay. Exclusion criteria were age <18 years, chronic persistent atrial fibrillation, history of systolic congestive heart failure (EF <40%), echocardiography-diagnosed valvular heart disease or valve replacement/s, implanted devices (pacemakers and/or implantable cardioverter defibrillators), and poor echocardiographic views (as agreed upon by two authors).

Data collection

Data were extracted from patients’ electronic medical records and included age, gender, year of admission, type of ICU admission, comorbid conditions, Sequential Organ Failure score in the first 24 hours of admission and on the day of echocardiography, and the time from the diagnosis of sepsis to the first echocardiographic exam. Clinical data such as haemodynamic data (heart rate, blood pressure, central venous pressure, cardiac index, systemic vascular resistance), type and amount of resuscitation fluid used, urine output, and net fluid balance were collected for the first 24 hours of ICU admission. Laboratory data included complete blood count, metabolic panel, serum albumin, serum troponins, arterial lactate, arterial blood gases, and alveolar-arterial oxygen tension difference during the first 24 hours of ICU admission. Vital signs including heart rate and arterial blood pressure (systolic, diastolic and mean) during the echocardiographic exam were obtained from the echocardiography report. Alcohol usage was also noted.

Echocardiographic data

Conventional echocardiographic study

Echocardiographic exams were performed using Philips iE-33 (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA and Bothell, WA, USA). The following data were obtained from the report: electrocardiograph, left atrial area, longitudinal and transverse dimensions, LV and RV end-systolic and end-diastolic transverse and longitudinal dimensions, LV EF, transmitral inflow velocity waveforms as recorded by pulsed-wave Doppler, left upper pulmonary venous velocity waveforms as recorded by pulsed-wave Doppler, lateral mitral annular tissue velocity as obtained by tissue Doppler imaging, ratios of early (E) to late (A) diastolic trans-mitral inflow velocity (E/A), and of early lateral mitral annular tissue velocity (E’) to early diastolic trans-mitral inflow velocity (E), E/E’. Fractional area change and inferior and interventricular septal wall thickness were also obtained.

Post-processing echocardiograph analysis

Prior to performing the echo analyses, the investigator on the study was trained on the Xcelera software (Philips Medical Systems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) by the vendors. Training was in the form of an off-site, two-day course as well as an on-site, full-day hands-on experience. The primary investigator performed the post-processing analysis STE using dedicated software (Xcelera), using the Philips QLAB version 4.1 cardiac motion quantification software (Philips Medical Systems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Images with maximum frame frequency (>50 frames/second) were selected for analysis.

The timing of mitral and aortic valve opening and closure to mark the different phases of the cardiac cycle was derived from spectral Doppler flow and the electrocardiograph. Afterward, the LV was divided into 16 segments as proposed by the American Society of Echocardiography16. Overall, for each patient we analysed 18 segments including: basal, mid and apical segments of the septal and lateral walls from the four-chamber view; inferior and anterior walls from the two-chamber view, and the inferolateral and anteroseptal walls from the three-chamber view. STE curves were then obtained in a semi-automated manner after manual tracing of the whole endocardial border, and subsequent generation of the corresponding regions of interest by the software. Measures obtained from three cardiac cycles were averaged to reduce noise and artefact errors. Once the correct recognition of the speckles by the software was assessed, the operator could choose to accept or reject the segments with suboptimal tracking after trying to manually adjust the borders to obtain a better tracking of the speckles. We decided not to measure the apical segments from the speckle-tracking analyses, given the consistent poor resolution of images acquired from these segments and the inability of the software to track them adequately. This resulted in 12 segments available for the analyses.

The average of values of all segments was then calculated and defined as the mean peak longitudinal systolic strain of the LV. By convention, shortening was given a negative value. Normal values of LVLS of ≤-15% (i.e. more negative or equal to) were based on published guidelines17.

The TMAD was measured in apical four- and two-chamber views using a two-dimensional (2D) strain-based tissue-tracking technique. Mitral annular motion was measured offline in the apical four- and two-chamber views using QLAB. For the evaluation of TMAD, we selected three regions of interest: 1) at the hinge points of the mitral valve leaflets to the septal and lateral walls for the apical four-chamber view; 2) at the anterior and inferior walls of the mitral annulus for the apical two-chamber view; and 3) at the LV apical endocardium. After setting the regions of interest, tracking was performed automatically. The degree of TMAD was then automatically calculated as the average of the baso-apical displacement of the hinge points of the mitral annulus as well as the midpoint between the hinge points (mm). Midpoint displacement was normalised to, and depicted as, a percentage of the LV long axis at end-diastole (TMAD midpoint %). The mean of three measures obtained during three cardiac cycles was used for the analysis. TMAD was evaluated on a global (average of all six segments) and segmental basis (individual segments in each of the apical four- and two-chamber views). A TMAD of ≥10 mm was considered normal18.

Study endpoints

The study endpoints were duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU and hospital lengths of stay, and in-hospital mortality.

Statistical analysis

Demographics, baseline characteristics, adverse outcomes and echocardiographic measures were summarised using descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation [SD] or frequency and percentage). Longitudinal strain and global TMAD were dichotomised as normal (LVLS ≤-15 mm/second, TMAD ≥10 mm) and abnormal (LVLS >-15 mm/second [i.e. less negative], TMAD <10 mm) and comparisons between groups were performed using a two-sample Student's t-test for continuous variables and chi-squared test (or Fisher's exact test) for categorical variables. If the assumptions of the statistical test were not met, an appropriate transformation was applied. The same procedures were used to test for associations between mortality and patient characteristics. Pearson's correlation analysis was performed to explore the relationships of selected echocardiographic variables. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant in two-tailed statistical tests. We did not correct for multiple comparisons since these analyses were exploratory in nature and performed using a small sample with high levels of missing values for several variables.

Intra- and inter-observer variability

The investigators, in a blinded fashion, abstracted echocardiography data. To ensure the accuracy and validity of echocardiographic readings, a random sample of 20 echocardiographic examinations for the estimation of TMAD and strain parameters were reviewed by the principal investigator at two reasonably spaced timepoints. The same evaluation procedure was also performed by a co-investigator who was blinded to the clinical information and to the initial measurement, had undergone the same training on the software, and performed these analyses on a routine daily basis in his echocardiography laboratory. Intra-class correlation coefficient was computed to assess the inter- and intra-observer reliability19,20. An intra-class correlation coefficient score of 0.75 or higher was considered as an acceptable reliability for our quality-control criterion.

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) software and the graphic presentation was created by R 3.0.2.

Results

Study population

A total of 97 patients were identified. Of those, 43 patients did not meet eligibility criteria and were excluded, leaving 54 patients for final analysis with echocardiograms performed within the first week of ICU admission (Figures 1 and 2). After excluding poor-quality images, the intra-class correlation coefficients for imaging quality within and between both echocardiographers passed our quality control criteria. Specifically TMAD was shown to have higher intra- and inter-rater reliability than global longitudinal strain (Table 1). Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample by LVLS and TMAD groups are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Overall, 74% of the patients had abnormal LVLS (>-15%) and 59% of the patients had abnormal TMAD (<10 mm). No significant differences were found in demographic and clinical characteristics, based on normal or abnormal LVLS values. Compared with patients with normal TMAD, those with abnormal TMAD tended to have higher weight (kg) (89.3 ± 27.8 versus 73.8 ± 22, P=0.036), higher central venous pressure (mm Hg) (10.4 ± 3.8 versus 7 ± 3.8, P=0.02), and higher positive 24-hour fluid balance (2.1 ± 0.8 versus 1.7 ± 0.7 litres, P=0.024). Patients with abnormal TMAD tended to have a higher sequential organ failure assessment score on the day of echocardiography compared with patients with normal TMAD.

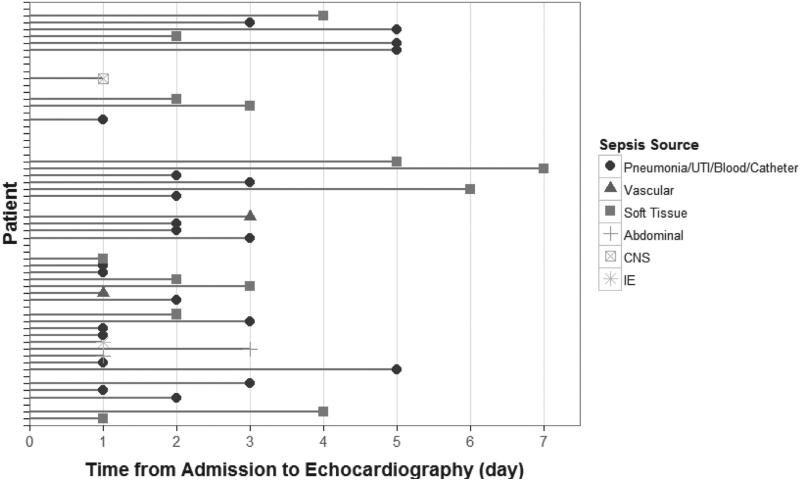

Figure 1.

Time from admission to the intensive care unit to first echocardiographic exam. Line heads are indicative of sepsis source. The time of admission to the ICU signals the diagnosis of sepsis. UTI=urinary tract infection, CNS=central nervous system, IE=infective endocarditis.

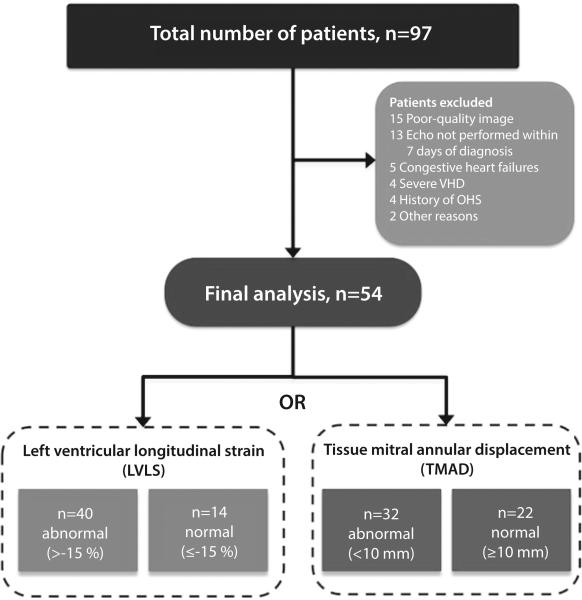

Figure 2.

Flow chart of patients included in the study. Out of 97 patients, 43 patients were excluded for different reasons, leaving 54 patients for final analysis. Normal refers to LVLS ≤-15 %, TMAD ≥10 mm. VHD=valvular heart disease, OHS=Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome.

Table 1.

Inter-rater and intra-rater reliability for TMAD and GLS

| Intra-rater Reliability | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | ICC1 | 95% CI | P-value |

| AZ2 | |||

| TMAD | 1 | (0.99, 1) | <0.0001* |

| GLS | 0.75 | (0.44, 0.89) | <0.0001* |

| EG3 | |||

| TMAD | 1 | (0.99, 1) | <0.0001* |

| GLS | 0.83 | (0.61, 0.93) | <0.0001* |

| Inter-rater Reliability | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | ICC1 | 95% CI | P-value |

| 1st Time | |||

| TMAD | 1 | (0.98, 1) | <0.0001* |

| GLS | 0.76 | (0.48, 0.9) | <0.0001* |

| 2nd Time | |||

| TMAD | 1 | (0.99, 1) | <0.0001* |

| GLS | 0.84 | (0.64, 0.93) | <0.0001* |

Intra-class correlation coefficients.

Rater AZ.

Rater EG.

Denotes statistical significance at P <0.05.

TMAD=tissue mitral annular displacement, GLS=global longitudinal strain.

Table 2.

Patients’ demographic and echocardiographic characteristics and study endpoints stratified by Left Ventricular Longitudinal Strain (LVLS)

| Characteristics | Left Ventricular Longitudinal Strain (LVLS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics, mean (SD) | Normal (n=14) | Abnormal (n=40) | P-value |

| Age, years | 51.2 (20.1) | 53.8 (12.6) | 0.68 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.49 | ||

| Male | 5 (41.7) | 11 (29.7) | |

| Female | 7 (58.3) | 26 (70.3) | |

|

Health Status and Comorbidities, mean (SD) | |||

| Weight (kg) | 72.9 (18.3) | 85.6 (28.3) | 0.17 |

| Heart rate, /minute | 88.4 (21.9) | 86.8 (19.5) | 0.81 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 5 (41.7) | 13 (35.1) | 0.74 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 3 (25) | 13 (35.1) | 0.73 |

| COPD, n (%) | 2 (16.7) | 5 (13.5) | 1.00 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 2 (16.7) | 8 (21.6) | 1.00 |

| Alcohol, n (%) | 0 (0) | 9 (24.3) | 0.09 |

| MAP, mmHg | 73.1 (19.2) | 76.1 (14.4) | 0.57 |

| MAP at time of echo, mmHg | 85.3 (14.8) | 83.9 (19) | 0.82 |

| Central venous pressure, mmHg | 7 (2.3) | 9.5 (4.4) | 0.17 |

| Creatinine, nmol/l | 177 (221) | 186 (1.8) | 0.92 |

| Pressor, n (%) | 3 (27.3) | 9 (26.5) | 1.00 |

| SOFA | 7.8 (3.7) | 8.7 (4.6) | 0.58 |

| SOFA, on day of echo | 6.4 (4.9) | 9.1 (4.3) | 0.13 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 10.3 (4.6) | 9.4 (4.8) | 0.61 |

| Lactate, mmol/l | 0.4 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.58 |

| Troponin I, μg/l | 15.7 (39.8) | 16.7 (73.4) | 0.97 |

| Fluid balance, litres | 1.6 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.7) | 0.06 |

| Sepsis Source | 0.33 | ||

| Pneumonia/UTI/Blood/Catheter | 6 (50) | 19 (54.3) | |

| Vascular | 1 (8.3) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Soft tissue | 3 (25) | 13 (37.1) | |

| Abdominal | 1 (8.3) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Central nervous system | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Infective endocarditis | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0) | |

|

Global Echo Variables, mean (SD) | |||

| Abnormal TMAD, n (%) | 2 (14.3) | 30 (75) | <0.001 |

| TMAD (Global) | 13.7 (3.4) | 7.9 (3.2) | <0.001 |

| TMAD 1AP2 | 14 (12) | 8.6 (7.2) | <.001 |

| TMAD 2AP2 | 13.9 (5.1) | 7.8 (4.8) | <.001 |

| TMAD MAP2 | 13.6 (3.6) | 8.1 (4) | <.001 |

| TMAD 1AP4 | 14.6 (5.2) | 7.2 (3) | <.001 |

| TMAD 2AP4 | 13.7 (4.5) | 8.1 (3.2) | <.001 |

| TMAD MAP4 | 14.1 (4.4) | 7.6 (3) | <.001 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 57.4 (5.9) | 49.1 (12.7) | <.003 |

| LV ESD, cm | 3 (0.8) | 3.4 (1) | 0.18 |

| LV EDD, cm | 4.4 (0.8) | 4.5 (0.8) | 0.67 |

| LA dimension, cm | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.9 (1) | 0.31 |

| LA maximal dimension, cm | 5.2 (1.4) | 5.7 (0.75) | 0.29 |

| LA minimal dimension, cm | 3.9 (0.6) | 4.1 (1) | 0.43 |

| E/E′ ratio | 14.1 (5.9) | 16.6 (9.9) | 0.51 |

| E/A ratio | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.45) | 0.52 |

| Fractional area change, % | 39.7 (11.7) | 32.2 (11.5) | 0.06 |

| LVEDV, ml | 94.6 (48.7) | 103.8 (45.2) | 0.53 |

| LVESV, ml | 45 (37.2) | 62.9 (33.7) | 0.10 |

|

Outcomes, mean (SD) | |||

| Death, n (%) | 6 (50) | 12 (33.3) | 0.33 |

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 21.6 (25) | 20.2 (22) | 0.85 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 41.3 (28.7) | 43.7 (48.3) | 0.88 |

| Length of mechanical ventilation (days) | 17.1 (26.9) | 14 (15.1) | 0.71 |

TMAD measured in mm. COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, MAP=mean arterial blood pressure, SOFA=Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, UTI=urinary tract infection, TMAD=tissue mitral annular displacement, TMAD 1AP2=tissue mitral annular displacement anterior in apical 2-chamber window, TMAD 2AP2=tissue mitral annular displacement inferior in apical 2-chamber window, TMAD MAP2=tissue mitral annular displacement midpoint in apical 2-chamber window, TMAD 1AP4=tissue mitral annular displacement anteroseptal in apical 4-chamber window, TMAD 2AP4=tissue mitral annular displacement anterolateral in apical 4-chamber window, TMAD MAP4=tissue mitral annular displacement midpoint in apical 2-chamber window, LV ESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume, EDV=end-diastolic volume, EDD=end-diastolic dimension, ESD=end-systolic dimension, LA=left atrial, E/E′=early trans-mitral inflow velocity to early lateral mitral annular tissue velocity ratio, E/A=ratio of early to late diastolic trans-mitral inflow velocity, ICU=intensive care unit, LVLS=left ventricular global longitudinal strain.

Table 3.

Patients’ demographic and echocardiographic characteristics and study endpoints stratified by Tissue Mitral Annular Displacement (TMAD)

| Characteristics | Tissue Mitral Annular Displacement (TMAD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics, mean (SD) | Normal (n=22) | Abnormal (n=32) | P-value |

| Age, years | 49.9 (17.2) | 55.4 (12.4) | 0.19 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.77 | ||

| Male | 7 (35) | 9 (31) | |

| Female | 13 (65) | 20 (69) | |

|

Health Status and Comorbidities, mean (SD) | |||

| Weight (kg) | 72.8 (22) | 89.3 (27.8) | 0.04 |

| Heart rate, /minute | 91 (20.8) | 84.2 (19) | 0.23 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 6 (30) | 12 (41.4) | 0.42 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 6 (30) | 10 (34.5) | 0.74 |

| COPD, n (%) | 3 (15) | 4 (13.8) | 1.00 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 2 (10) | 8 (27.6) | 0.17 |

| Alcohol, n (%) | 1 (5) | 8 (27.6) | 0.06 |

| MAP, mmHg | 74 (16.1) | 76.4 (15.5) | 0.60 |

| MAP, at time of echo, mmHg | 86.7 (13) | 82.8 (20.3) | 0.48 |

| Central venous pressure, mmHg | 7 (3.8) | 10.4 (3.8) | 0.02 |

| Creatinine, nmol/l | 150 (150) | 203 (185) | 0.32 |

| Pressor, n (%) | 4 (22.2) | 8 (29.6) | 0.74 |

| SOFA | 7.9 (3.3) | 8.8 (5) | 0.52 |

| SOFA, on day of echo | 6.7 (4.8) | 9.6 (4) | 0.06 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 9.3 (4.7) | 9.9 (4.8) | 0.67 |

| Lactate, mmol/l | 0.4 (0.3) | 0.25 (0.2) | 0.04 |

| Troponin I, μg/l | 9.1 (30.5) | 21.4 (82.8) | 0.57 |

| Fluid balance, litres | 1.7 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.8) | 0.02 |

| Sepsis Source | 0.33 | ||

| Pneumonia/UTI/Blood/Catheter | 11 (55) | 14 (51.9) | |

| Vascular | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | |

| Soft tissue | 4 (20) | 12 (44.4) | |

| Abdominal | 1 (5) | 1 (3.7) | |

| Central nervous system | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| Infective endocarditis | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | |

|

Global Echo Variables, mean (SD) | |||

| Ejection fraction, % | 57.3 (5.6) | 47.5 (13.1) | 0.001 |

| LV ESD, cm | 3 (0.8) | 3.4 (1.1) | 0.22 |

| LV EDD, cm | 4.4 (0.7) | 4.4 (0.9) | 0.70 |

| LA dimension, cm | 3.7 (0.7) | 4 (1) | 0.28 |

| LA maximal dimension, cm | 5.5 (1.2) | 5.6 (0.8) | 0.88 |

| LA minimal dimension, cm | 3.8 (3.4) | 4.2 (3.7) | 0.27 |

| E/E′ ratio | 15.8 (9) | 16 (9.2) | 0.97 |

| E/A ratio | 1.3 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.5) | 0.48 |

| Fractional area change, % | 39.1 (10.6) | 30.8 (11.8) | 0.02 |

| LVEDV, ml | 85.2 (29.5) | 110.8 (51.4) | 0.03 |

| LVESV, ml | 39.3 (19) | 69.1 (38.1) | <0.001 |

|

Regional Echo Variables, mean (SD) | |||

| LVLS, n (%) | 10 (45.5) | 30 (93.8) | <0.001 |

| LVLS | −13.9 ± 4.3 | −7.5 ± 3 | <0.001 |

| Basal anterior | −11.4 (11.6) | −7.7 (11) | 0.30 |

| Basal anterolateral | −18.8 (15.4) | −6 (10.6) | <0.001 |

| Basal anteroseptal | −8.2 (12) | −3.3 (10.2) | 0.15 |

| Basal inferior | −20.6 (12.1) | −8.1 (10.9) | <0.001 |

| Basal inferolateral | −13.7 (10.7) | −7.2 (13.2) | 0.13 |

| Basal inferoseptal | −11.1 (12.3) | −5.5 (7.1) | 0.06 |

| Mid-anterior | −13 (12.2) | −8.2 (9.4) | 0.15 |

| Mid-anterolateral | −11 (10.3) | −4.9 (7.3) | 0.02 |

| Mid-anteroseptal | −10.6 (8.3) | −9.6 (7.9) | 0.70 |

| Mid-inferior | −16.7 (10.3) | −7.6 (7.8) | 0.01 |

| Mid-inferolateral | −16.6 (13.7) | −6.6 (13) | 0.03 |

| Mid-inferoseptal | −16.8 (21.6) | −7.1 (7.1) | 0.02 |

|

Outcomes, mean (SD) | |||

| Death, n (%) | 6 (30) | 12 (42.9) | 0.36 |

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 26.7 (26.4) | 16.1 (18.5) | 0.11 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 52.7 (30.6) | 36.2 (50.9) | 0.17 |

| Length of mechanical ventilation (days) | 18.8 (23.9) | 12 (13.1) | 0.25 |

LVLS measurement in percentage. COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, MAP=mean arterial blood pressure, SOFA=Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, UTI=urinary tract infection, TMAD=tissue mitral annular displacement, LV ESV=left ventricular end-systolic volume, EDV=end-diastolic volume, EDD=end-diastolic dimension, ESD=end-systolic dimension, LA=left atrial, E/E′=early trans-mitral inflow velocity to early lateral mitral annular tissue velocity ratio, E/A=ratio of early to late diastolic trans-mitral inflow velocity, ICU=intensive care unit, LVLS=left ventricular global longitudinal strain.

Primary analyses: echocardiographic variables of interest and study endpoints

Left ventricular systolic longitudinal strain

There was no significant difference in mortality, hospital or ICU length of stay, or duration of mechanical ventilation between patients with abnormal and normal LVLS. There was a suggestion that abnormal LVLS was associated with a higher hospital mortality compared to those with a normal LVLS but this was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Tissue mitral annulus displacement

There was no significant difference between abnormal and normal groups in the study endpoints. There was a suggestion that abnormal TMAD group was associated with a higher hospital mortality, a shorter hospital and ICU stay, as well as fewer days on mechanical ventilation, compared with the normal TMAD group (Table 3).

Exploratory analyses: characterisation of echocardiographic variables

Global indices

The following global echocardiographic variables were significantly different between patients with abnormal versus normal LVLS (Table 2): global TMAD (mean, SD 7.9 mm ± 3.2, versus 13.7 ± 3.4, P <0.001) and LV EF (49.1% ± 12.7 versus 57.4 ± 5.9, P <0.003) were lower in the abnormal compared with the normal LVLS group. LV end-systolic and diastolic volumes and endocardial fractional shortening tended to be larger in the abnormal versus the normal LVLS group.

The following global echocardiographic variables were different in patients with abnormal versus normal TMAD (Table 3): EF (47.5% ± 13.1 versus 57.3 ± 5.6, P=0.001), endocardial fractional shortening (30.8% ± 11.8 versus 39.1 ± 10.6, P=0.02), global LVLS (−7.5% ± 3 versus −13.9 ± 4.3), and LV end-diastolic (110.8 ml ± 51.4 versus 85.2 ± 29.5, P=0.03) and end-systolic volumes (69.1 ml ± 38.1 versus 39.3 ± 19, P <0.001), which were all lower in the abnormal TMAD group.

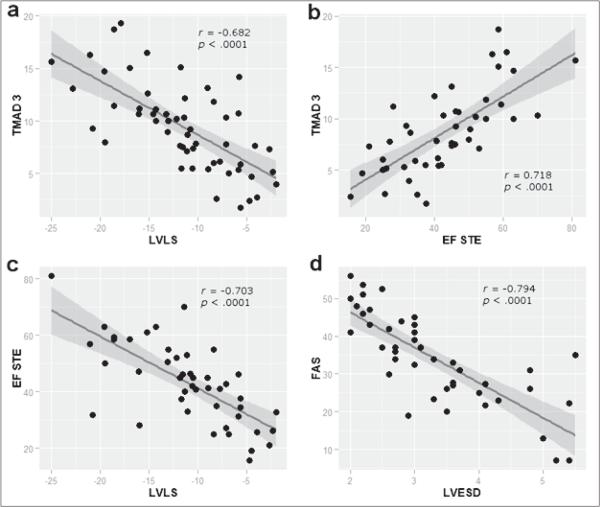

We found significant correlations between global TMAD and both global LVLS (r=−0.682, P <0.001) and EF (r=0.718, P <0.001). Similarly, between global LVLS and EF (r=−0.703, P <0.001) and fractional area shortening and LV end-systolic volume (r=−0.794, P <0.001, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Scatter plots for correlated echocardiographic variables with fitted regression lines. a) negative correlation between global tissue mitral annular displacement and global left ventricular strain (r=−0.682); b) positive correlation between global tissue mitral annular displacement and EF (r=0.718); c) negative correlation between EF measured by speckle-tracking echocardiography and global left ventricular systolic longitudinal strain (r=−0.703); and d) negative correlation between fractional area of shortening and left ventricular end-systolic dimension (r=−0.794). All correlations were statistically significant, P <0.001. TMAD3=global tissue mitral annular displacement, EF=ejection fraction, LVLS=global left ventricular systolic longitudinal strain, FAS=fractional area of shortening, STE=speckle-tracking echocardiography, LVESD=left ventricular end-systolic dimension.

Regional indices

All six TMAD segments (anterior, inferior, anteroseptal, inferolateral and midpoint in each of apical four and apical two windows) were significantly reduced in the abnormal LVLS group (P <0.001) (Table 2). The following segmental strains were significantly reduced in the abnormal compared to the normal TMAD group: and basal anterolateral inferior (P <0.001); and mid-segments (mid-inferior, P <0.001, mid-inferolateral, P=0.03, mid-inferoseptal, P=0.02), with the exception of mid-anterior and mid-anteroseptal segments.

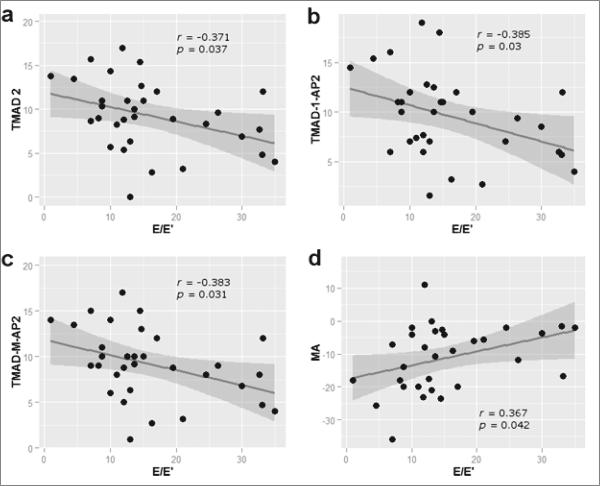

Segmental LVLS and TMAD inversely correlated with LV diastolic function. Mid-anterior segmental strain positively correlated (r=0.36, P=0.04), while anterolateral TMAD at apical four-chamber (r=−0.37, P=0.03), anterior (r=−0.38, P=0.03) and midpoint TMAD (r=−0.38, P=0.03) at apical two-chamber window inversely correlated with LV lateral mitral annular E/E’ ratio (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Scatter plots for correlations between LV strain and tissue mitral annular displacement and diastolic function. a) The anterolateral TMAD at apical 4-chamber correlated inversely with E/E’ (r=−0.37, P=0.03); b) anterior TMAD at apical 2-chamber correlated negatively with E/E’ (r=−0.38, P=0.03); c) midpoint TMAD at apical 2-chamber correlated inversely with E/E’ (r=−0.38, P=0.03); d) mid-anterior segmental strain correlated positively with E/E’ (r=0.36, P=0.04). TMAD-2=anterolateral TMAD at apical 4-chamber window, TMAD 1-AP-2=anterior TMAD at apical 2-chamber window, TMAD-M-Ap-2=midpoint TMAD at apical 2-chamber window, MA=mid-anterior segmental strain, E/E’=ratio of early trans-mitral inflow velocity to early lateral mitral annular tissue velocity.

Only Sequential Organ Failure score on the day of echocardiography and LV basal anterior segmental longitudinal strain were significantly associated with increased hospital mortality (P=0.01) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Associations of patient characteristics with mortality

| Demographic, mean (SD) | Alive (n=33) | Dead (n=20) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 51.6 (16.3) | 56.4 (10.7) | 0.21 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.12 | ||

| Male | 8 (24.2) | 9 (45) | |

| Female | 25 (75.8) | 11 (55) | |

|

Health Status and Comorbidities | |||

| Weight (kg) | 84.6 (29.8) | 76.1 (17) | 0.20 |

| Heart rate, /minute | 86.8 (19) | 85.1 (20.5) | 0.75 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 8 (24.2) | 11 (55) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 9 (27.3) | 6 (30) | 0.83 |

| COPD, n (%) | 4 (12.1) | 2 (10) | 1.00 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 5 (15.2) | 4 (20) | 0.72 |

| Alcohol, n (%) | 6 (18.2) | 4 (20) | 1.00 |

| MAP, mmHg | 76.3 (14.6) | 72.1 (16.1) | 0.33 |

| MAP, at time of echo, mmHg | 83.2 (14.9) | 85.9 (23.3) | 0.67 |

| Central venous pressure, mmHg | 9.3 (4.2) | 8.1 (4.2) | 0.4 |

| Creatinine, μmol/l | 141 (124) | 278 (221) | 0.13 |

| Pressor, n (%) | 8 (25.8) | 7 (36.8) | 0.41 |

| SOFA | 9 (7.3) | 9.7 (4.3) | 0.67 |

| SOFA, on day of echo | 7.2 (3.8) | 11.1 (4.3) | 0.01 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 9.5 (4.5) | 8.9 (5) | 0.60 |

| Lactate, mmol/l | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.35) | 0.19 |

| Troponin I, μg/l | 21.5 (77.4) | 2 (3.8) | 0.25 |

| Fluid balance, litres | 1.8 (0.5) | 2.1 (1) | 0.29 |

| Sepsis Source | 0.38 | ||

| Pneumonia/UTI/Blood/Catheter | 19 (57.6) | 9 (47.4) | |

| Vascular | 1 (3) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Soft tissue | 10 (30.3) | 7 (36.8) | |

| Abdominal | 0 (0) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Central nervous system | 2 (6.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Infective endocarditis | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | |

|

Global Echo Variable | |||

| Ejection fraction, % | 52.4 (11.1) | 48.8 (13.5) | 0.33 |

| LV ESD, cm | 3.3 (1) | 3.2 (1) | 0.67 |

| LV EDD, cm | 4.4 (0.8) | 4.4 (0.6) | 0.77 |

| LA dimension, cm | 4 (1) | 3.7 (0.6) | 0.30 |

| LA maximal dimension, cm | 5.9 (0.9) | 5.1 (1) | 0.03 |

| LA minimum dimension, cm | 4 (3.5) | 4.2 (3.8) | 0.52 |

| E/E' ratio | 16.9 (11.2) | 16.3 (5.1) | 0.84 |

| E/A ratio | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.5) | 0.77 |

| Fractional area change, % | 34.6 (9.4) | 32.8 (16.1) | 0.70 |

| LVEDV, ml | 104.8 (46.7) | 99.7 (49.9) | 0.70 |

| LVESV, ml | 59.4 (33.2) | 60.7 (40.3) | 0.90 |

|

Regional Echo Variable | |||

| Abnormal LVLS, n (%) | 24 (80) | 12 (66.7) | 0.33 |

| Basal anterior | −13.1 (11) | −2.4 (10.5) | 0.01 |

| Basal anterolateral | −11.8 (13.9) | −10.6 (16) | 0.78 |

| Basal anteroseptal | −6.5 (10.9) | −4.9 (13.8) | 0.71 |

| Basal inferior | −10.9 (10.1) | −14.8 (14.3) | 0.33 |

| Basal inferolateral | −9 (8.7) | −12.6 (16.9) | 0.54 |

| Basal inferoseptal | −7.2 (9.8) | −9.4 (10.9) | 0.48 |

| Mid-anterior | −7.6 (10.3) | −12.1 (9.7) | 0.19 |

| Mid-anterolateral | −5.4 (9.6) | −9.7 (8.3) | 0.13 |

| Mid-anteroseptal | −8.7 (−11.7) | −11 (−18.3) | 0.46 |

| Mid-inferior | −11.6 (8.7) | −7.9 (7.2) | 0.19 |

| Mid-inferolateral | −10.5 (14.1) | −8.9 (17.7) | 0.79 |

| Mid-inferoseptal | −7.5 (8.1) | −16.7 (23.1) | 0.12 |

| TMAD, n (%) | 16 (53.3) | 12 (66.7) | 0.36 |

| TMAD (Global) | 9.7 (4) | 8.7 (4.5) | 0.44 |

| TMAD 1AP2 | 10.2 (4.7) | 9 (4.3) | 0.41 |

| TMAD 2AP2 | 9.4 (5.8) | 8.5 (5.9) | 0.63 |

| TMAD MAP2 | 9.8 (4.8) | 8.5 (4.6) | 0.42 |

| TMAD 1AP4 | 9.3 (4.3) | 8.8 (5.8) | 0.73 |

| TMAD 2AP4 | 9.9 (3.6) | 9.1 (5.3) | 0.55 |

| TMAD MAP4 | 9.5 (3.8) | 8.9 (5.4) | 0.68 |

|

Outcomes | |||

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 17.9 (18.9) | 22.9 (25.5) | 0.42 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 48.8 (48.5) | 28.4 (26.2) | 0.05 |

| Length of mechanical ventilation (days) | 12.8 (7.3) | 15.8 (6) | 0.57 |

LVLS measurments in percentage, TMAD measurements in mm. COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, MAP=mean arterial blood pressure, SOFA=Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, UTI=urinary tract infection, TMAD=tissue mitral annular displacement, TMAD 1AP2=tissue mitral annular displacement anterior in apical 2-chamber window, TMAD 2AP2=tissue mitral annular displacement inferior in apical 2-chamber window, TMAD MAP2=tissue mitral annular displacement midpoint in apical 2-chamber window, TMAD 1AP4=tissue mitral annular displacement anteroseptal in apical 4-chamber window, TMAD 2AP4=tissue mitral annular displacement anterolateral in apical 4-chamber window, TMAD MAP4=tissue mitral annular displacement midpoint in apical 2-chamber window, LV ESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume, EDV=end-diastolic volume, EDD=end-diastolic dimension, ESD=end-systolic dimension, LA=left atrial, E/E'=early trans-mitral inflow velocity to early lateral mitral annular tissue velocity ratio, E/A=ratio of early to late diastolic trans-mitral inflow velocity, ICU=intensive care unit, LVLS=left ventricular global longitudinal strain.

Echocardiographic variables and serum biomarkers

There was no correlation between global and segmental LVLS and TMAD and either serum troponin and lactate.

Discussion

This study highlights the importance of and the complementary role played by global and segmental indices of LV deformation in characterising sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction and predicting outcomes in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. We found that reduction in both global and segmental LVLS and TMAD correlated with systolic and diastolic dysfunction in patients with septic shock. Additionally, reduced longitudinal strain of the basal anterior segment was associated with an increase in hospital mortality and there was a suggestion that reduced LV global TMAD may be associated with increased hospital mortality. Taken together, the association of reduced TMAD with increased fluid balance can lead us to hypothesise that an increase in venous return leads to an increase in LV volumes, impairing diastolic function and hence, TMAD. The present fact highlights that these patients, with high circulating blood volume, operate on the flat part of the Frank–Starling curve. From a physiological point of view, it is well known that the plateau part of the curve is associated with a major decrease in both LV compliance and LV longitudinal shortening. It is to be mentioned, however, that at this stage this assumption is only hypothesis-generating, given the different timepoints at which echocardiographic assessment was performed in relation to time of collecting data on fluid balance.

In recent years, there has been an increased interest in applying advanced echocardiographic techniques such as speckle tracking in characterising LV function in sepsis. Speckle-tracking technology is a feasible technique in studying the cardiac function of the critically ill since it relies on software analysis of conventional bedside echocardiographic examinations. Different vendors provide training on speckle tracking. With speckle-tracking technology, it is now more feasible to obtain information about myocardial deformation only obtainable in the past by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Global longitudinal strain measured by speckle-tracking echocardiography has gained popularity, in part, due to the longitudinal arrangement of the more vulnerable subendocardial fibres of the LV across this plane of motion, thus potentially representing an early marker of LV systolic dysfunction in sepsis. While the concept of measuring the global longitudinal strain as a marker of tissue deformation is appealing, global patterns may mask severely diseased segments that may not be demonstrated in the calculation of a global index. However, longitudinal strain measurements require high-quality images and are both time-consuming and operator-dependent5. In this study, we sought to use TMAD, in conjunction with LVLS, as less time-consuming yet sensitive markers of LV systolic function. We sought to use TMAD both as a global and as a segmental index of LV systolic function to assess its ability to predict adverse outcomes in severe sepsis and septic shock. To our knowledge, our study is the first to report on TMAD using STE in this patient population. Novel enough, our study proved that TMAD has a higher inter- and intra-observer reliability than LVLS in a busy clinical ICU setting. It is also the first study to report on the relationship between both global and segmental TMAD and LVLS and relevant sepsis outcomes. In this regard, a reduction in both global and segmental TMAD significantly correlated with a reduction in LVLS and EF. The mitral annulus is part of the fibrous skeleton of the heart to which longitudinally arranged fibres that span the distance between the base and the apex are attached. During systole these fibres shorten to move the base closer to the apex, rather than the reverse. It is therefore reasonable to assume, with the apex being a reference point, that TMAD reflects the longitudinal displacement of the heart during systole and diastole. It has been suggested that longitudinal shortening accounts for greater than 70% of the EF21. Our findings are consistent with other studies that have shown TMAD to be an earlier marker of systolic dysfunction than EF in multiple settings12. As TMAD is related to longitudinal displacement, it is reasonable to find a correlation between the present marker and LVLS globally and/or segmentally. Indeed, impaired shortening (strain) of segments between LV base and apex may, in part or in total, impair the longitudinal displacement of the mitral annulus from base to apex.

Only a few studies have used STE to investigate the relationship between ventricular dysfunction in sepsis and outcomes. A recent study performed by Landesberg et al10 demonstrated, using 3D STE, that an increase in RV end-systolic volume index as well as an increase in LV trans-mitral to mitral annulus strain rate ratio were both associated with increased serum troponins and in-hospital mortality. Our study is different from that of Landesberg et al in that the latter used 3D echocardiography to assess biventricular volumes. Because it assesses the heart in its entirety, 3D volumetric assessment is more accurate, more reproducible and more sensitive to the complex ventricular structure compared with 2D echocardiography22. It is to be mentioned though, that 3D speckle tracking provides a more complete, in plane and faster strain tracking compared with 2D speckle tracking, yet at the expense of a lower temporal resolution23,24. The superior versatility of 2D speckle tracking–measured strain rate used in Landesberg et al compared with tissue Doppler imaging used in our study may explain the difference in detection of diastolic dysfunction in Landesberg et al's study compared to ours. Importantly, Landesberg et al's study explored the association between global strain and mortality, it did not measure TMAD, nor did it measure segmental strain values of the LV. While we did not find an association between global LVLS and mortality, reduction of the basal anterior segmental strain was associated with increased mortality. The present finding is of interest as the LV base is the site of the higher peak systolic radial velocities of the anterior and inferior segments25, suggesting the relatively higher dynamics of anteroposterior versus lateral ventricular wall motion in systole25. Likewise, there was a suggestion of an increase in mortality in patients with abnormal TMAD. The association between segmental strain and sepsis outcomes needs to be explored in future studies.

Failure of global LVLS to predict mortality in patients with septic shock is consistent with recent observations by de Geer et al26 who demonstrated that global LVLS correlated with initial LV EF, and that it did not differentiate between survivors and non-survivors. The lack of an association between mean peak systolic LV strain and mortality was also recently reported in a study by Orde et al11 using STE to measure biventricular longitudinal strains. The authors observed that speckle tracking unmasked biventricular systolic dysfunction that was not detected by EF. Severe reduction in RV free wall strain, but not LV systolic strain, was associated with six-month mortality.

Our study also demonstrated a significant inverse correlation between fractional area shortening and LV end-diastolic volume, highlighting the relationship between ventricular dimension and contractility. This concept has been termed ‘preload adaptation’ and has been variably reported and debated in patients with sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction, and the relationship between chamber dimensions and function, and survivorship, has been an inconsistent finding in studies describing sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction1–4. Our study demonstrates that an increase in LV end-diastolic volumes had no relationship with mortality. In contrast to the studies by Parker et al1, Vieillard Baron et al4, and Bouhemad et al3, we did not perform serial echocardiographic exams, but we used the more advanced speckle-tracking methodology to assess left ventricular function. As a result of our protocol, we might have missed a change in chamber size during the course of sepsis. Differences in study design, timepoints of echocardiographic exams, and in the follow-up of patients with sepsis, as well as differences in the tools of assessing cardiac function largely explains the inconsistency in chamber sizes and their relationship to mortality. Our results are in line with a recent meta-analysis27, which assessed the relationship between biventricular function, dimension and mortality in over 700 patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. The authors demonstrated that there were no significant differences in biventricular EF between survivors and non-survivors of severe sepsis and septic shock. The authors also demonstrated that indexed biventricular dimensions were not significantly different between survivors and non-survivors. Non-indexed LV dimensions were significantly larger in survivors compared with non-survivors. However, this meta-analysis did not include recent studies that used speckle-tracking technology to assess ventricular strain as a surrogate of ventricular function.

Our study did not identify a correlation between echocardiographic variables and serum troponins. This finding is in contrast with the findings of Bouhemad et al3 who demonstrated an association between LV end-diastolic area and serum troponins independent of kidney function. It is also in contrast with Landesberg et al10 who demonstrated an association between RV end-systolic volume index and serum troponins. Elevated cardiac troponins have been associated with LV systolic dysfunction in severe sepsis and septic shock28 and have been associated with the duration of hypotension, the intensity of vasopressor therapy, and higher mortality29. Despite reports of elevated troponins, there has been no evidence of myocardial structural necrosis or cell death in human hearts with sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction30 or animal models of septic shock31, therefore attributing their elevation to an increase in myocardial membrane permeability in response to inflammatory mediators32. Moreover, an organ dysfunction like acute renal failure, which is commonly associated with septic shock, may explain all these inconsistencies. More studies are needed to demonstrate the effects of the relationship between serum troponins and markers of ventricular deformation in sepsis.

Our study has several limitations. Our study design was retrospective in nature, had a relatively small sample size, and relied on 2D technology in assessing ventricular volumes. In addition, we used tissue Doppler technology in assessing diastolic dysfunction. The software version used to perform speckle tracking led to exclusion of many images. The use of TMAD, however, overcomes this shortcoming since it does not require high-quality images, is relatively faster, and is reliable to acquire. In the present study, we did not measure RV strain, or RV EF. It is important to highlight the timing and the retrospective nature of our study, which might have played a role in the difference between our study and that of Landesberg et al's10. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, we included echocardiographic examinations performed within the first week of ICU admission and not necessarily within the first 24 hours of diagnosis of severe sepsis and septic shock. Additionally, it was not possible to serially follow the progression and resolution of sepsis, or to ascribe the findings of this study to a particular stage of sepsis progression. Another consequence of the retrospective nature of the study was that the fluid and vasopressors were managed by the primary care teams. However, at our institution we have a standardised protocol for the management of sepsis. Also, owing to the retrospective nature of the study, we were unable to perform a time-to-event (death) analysis which might have confirmed the association between shorter lengths of hospital and ICU stay and hospital mortality in the abnormal TMAD group. Additionally, since the study was not adequately powered to study mortality and since given the lack of agreement between vendors on values of segmental strain, the relationship between basal anterior segmental strain and mortality should be interpreted with caution and is hypothesis-generating at the present time.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates that STE is a feasible option in critically ill patients, and that TMAD might be a less time-consuming option for assessing cardiac systolic function. This study also shows that there is a decline in global and segmental TMAD and LVLS in a population of patients with sepsis. We found a correlation between global and segmental TMAD and LVLS and echocardiographic indices of systolic and diastolic function. Future echocardiographic studies should prospectively study both segmental and global echocardiographic indices and the relationship with biomarkers of cardiac dysfunction at different stages of the sepsis progression.

Acknowledgements

Statistical analysis of research reported in this publication was partially supported by the National Centre for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number UL1TR00165.

References

- 1.Parker MM, Shelhamer JH, Bacharach SL, Green MV, Natanson C, Frederick TM, et al. Profound but reversible myocardial depression in patients with septic shock. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:483–490. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-4-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parker MM, McCarthy KE, Ognibene FP, Parrillo JE. Right ventricular dysfunction and dilatation, similar to left ventricular changes, characterize the cardiac depression of septic shock in humans. Chest. 1990;97:126–131. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouhemad B, Nicolas-Robin A, Arbelot C, Arthaud M, Feger F, Rouby JJ. Acute left ventricular dilatation and shock-induced myocardial dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:441–447. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318194ac44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vieillard BA, Schmitt JM, Beauchet A, Augarde R, Prin S, Page B, et al. Early preload adaptation in septic shock? A transesophageal echocardiographic study. Anesthesiology. 2001;94:400–406. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200103000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buss SJ, Mereles D, Emami M, Korosoglou G, Riffel JH, Bertel D, et al. Rapid assessment of longitudinal systolic left ventricular function using speckle tracking of the mitral annulus. Clin Res Cardiol. 2012;101:273–280. doi: 10.1007/s00392-011-0389-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaky A, Deem S, Bendjelid K, Treggiari MM. Characterization of cardiac dysfunction in sepsis: an ongoing challenge. Shock. 2014;41:12–24. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanderson JE, Fraser AG. Systolic dysfunction in heart failure with a normal ejection fraction: echo-Doppler measurements. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;49:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helle-Valle T, Crosby J, Edvardsen T, Lyseggen E, Amundsen BH, Smith HJ, et al. New noninvasive method for assessment of left ventricular rotation: speckle tracking echocardiography. Circulation. 2005;112:3149–3156. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.531558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basu S, Frank LH, Fenton KE, Sable CA, Levy RJ, Berger JT. Two-dimensional speckle tracking imaging detects impaired myocardial performance in children with septic shock, not recognized by conventional echocardiography. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:259–264. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182288445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landesberg G, Jaffe AS, Gilon D, Levin PD, Goodman S, Abu-Baih A, et al. Troponin elevation in severe sepsis and septic shock: the role of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and right ventricular dilatation*. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:790–800. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orde SR, Pulido JN, Masaki M, Gillespie S, Spoon JN, Kane GC, et al. Outcome prediction in sepsis: speckle tracking echocardiography based assessment of myocardial function. Crit Care. 2014;18:R149. doi: 10.1186/cc13987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu L, Tuo S, Zhang J, Zuo L, Liu F, Hao L, et al. Reduction of left ventricular longitudinal global and segmental systolic functions in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Study of two-dimensional tissue motion annular displacement. Exp Ther Med. 2014;7:1457–1464. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishikage T, Nakai H, Lang RM, Takeuchi M. Subclinical left ventricular longitudinal systolic dysfunction in hypertension with no evidence of heart failure. Circ J. 2008;72:189–194. doi: 10.1253/circj.72.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Q, Fung JWH, Yip GWK, Chan JYS, Lee APW, Lam YY, et al. Improvement of left ventricular myocardial short-axis, but not long-axis function or torsion after cardiac resynchronisation therapy: an assessment by two-dimensional speckle tracking. Heart. 2008;94:1464–1471. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.127498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voigt JU, Pedrizzetti G, Lysyansky P, Marwick TH, Houle H, Baumann R, et al. Definitions for a common standard for 2D speckle tracking echocardiography: consensus document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to standardize deformation imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alam M, Hoglund C, Thorstrand C, Hellekant C. Haemodynamic significance of the atrioventricular plane displacement in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 1992;13:194–200. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu S, Crespi CM, Wong WK. Comparison of methods for estimating the intraclass correlation coefficient for binary responses in cancer prevention cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:869–880. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlsson M, Ugander M, Mosen H, Buhre T, Arheden H. Atrioventricular plane displacement is the major contributor to left ventricular pumping in healthy adults, athletes, and patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1452–H1459. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01148.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruddox V, Mathisen M, Baekkevar M, Aune E, Edvardsen T, Otterstad JE. Is 3D echocardiography superior to 2D echocardiography in general practice? A systematic review of studies published between 2007 and 2012. Int J Cardiol 2013. 168:1306–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seo Y, Ishizu T, Atsumi A, Kawamura R, Aonuma K. Three-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography. Circ J. 2014;78:1290–1301. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-14-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez de Isla L, Balcones DV, Fernandez-Golfin C, Marcos-Alberca P, Almeria C, Rodrigo JL, et al. Three-dimensional-wall motion tracking: a new and faster tool for myocardial strain assessment: comparison with two-dimensional-wall motion tracking. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Codreanu I, Robson MD, Rider OJ, Pegg TJ, Dasanu CA, Jung BA, et al. Details of left ventricular radial wall motion supporting the ventricular theory of the third heart sound obtained by cardiac MR. Br J Radiol. 2014;87:20130780. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20130780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Geer L, Engvall J, Oscarsson A. Strain echocardiography in septic shock - a comparison with systolic and diastolic function parameters, cardiac biomarkers and outcome. Crit Care. 2015;19:122. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0857-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang SJ, Nalos M, McLean AS. Is early ventricular dysfunction or dilatation associated with lower mortality rate in adult severe sepsis and septic shock? A meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2013;17:R96. doi: 10.1186/cc12741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ver Elst KM, Spapen HD, Nguyen DN, Garbar C, Huyghens LP, Gorus FK. Cardiac troponins I and T are biological markers of left ventricular dysfunction in septic shock. Clin Chem. 2000;46:650–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehta NJ, Khan IA, Gupta V, Jani K, Gowda RM, Smith PR. Cardiac troponin I predicts myocardial dysfunction and adverse outcome in septic shock. Int J Cardiol. 2004;95:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takasu O, Gaut JP, Watanabe E, To K, Fagley RE, Sato B, et al. Mechanisms of cardiac and renal dysfunction in patients dying of sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:509–517. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201211-1983OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou M, Wang P, Chaudry IH. Cardiac contractility and structure are not significantly compromised even during the late, hypodynamic stage of sepsis. Shock. 1998;9:352–358. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199805000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu AH. Increased troponin in patients with sepsis and septic shock: myocardial necrosis or reversible myocardial depression? Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:959–961. doi: 10.1007/s001340100970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]