Abstract

Mutations in mitochondrial IDH2, one of the three isoforms of IDH, were discovered in patients with gliomas in 2009 and subsequently described in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), chondrosarcoma and intrahepatic chloangiocarcinoma. The effects of mutations in IDH2 on cellular metabolism, the epigenetic state of mutated cells, and cellular differentiation have been elucidated in-vitro and in-vivo. Mutations in IDH2 lead to an enzymatic gain of function that catalyzes the conversion of alpha-ketoglutarate to beta-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG). Supra-normal levels of 2-HG lead to hypermethylation of epigenetic targets and a subsequent block in cellular differentiation. AG-221, a small molecule inhibitor of mutant IDH2, is being explored in a phase 1 clinical trial for the treatment of AML, other myeloid malignancies, solid tumors and gliomas.

Background

Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) catalyzes the conversion of isocitrate to alpha-ketoglutarate. IDH occurs in three isoforms, IDH1, located in the cytoplasm, IDH2 located in the mitochondria and IDH3 which functions as part of the TCA cycle. Mutations in the active site of IDH1 at position R132 were discovered in 2008 during an integrated genomic analysis of 22 human glioblastoma samples (1). In 2009, an analogous mutation in the IDH2 gene at position R172 was discovered in patients with gliomas including astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas (2). Subsequently, mutations in IDH2 at residue R172 were discovered in chondrosarcomas, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphomas (AITL), and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (3-5). In addition, mutations in both R172 and R140 are found in approximately 15-20% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (6, 7). IDH2 mutations predominate in hematologic malignancies (AML, AITL) while IDH1 mutations predominate in solid tumors (Glioma, Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma). Among the hematologic malignancies, R140 mutations predominate in AML, while R172 predominate in AITL.

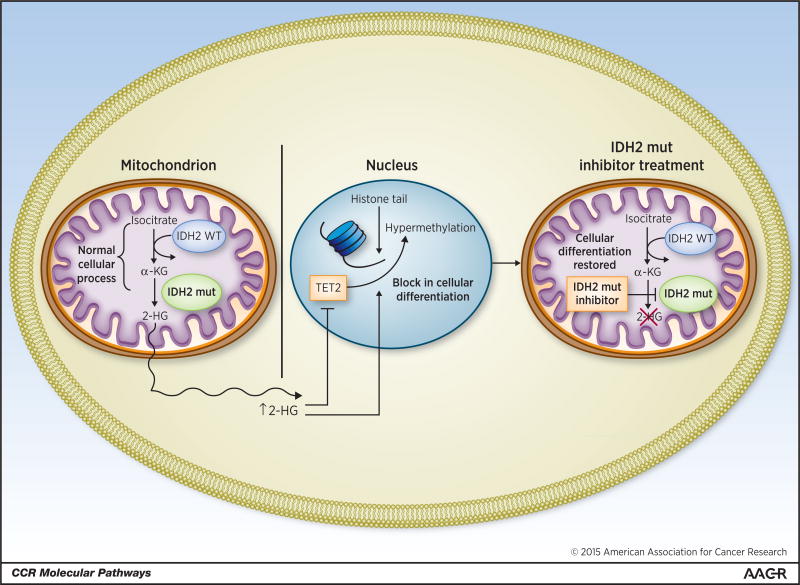

IDH2 mutants, like their abnormal IDH1 counterparts, confer a gain-of-function, and lead to neomorphic enzymatic activity (6). Instead of catalyzing the conversion of isocitrate to alpha-ketogluatarate, R172 and R140 mutant IDH2 both catalyze the conversion of alpha ketoglutarate to beta-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG). Supra-normal levels of intracellular 2-HG lead to hypermethylation of target genes. In vitro studies demonstrate a significant increase in 5-methylcytosine in cells expressing mutant IDH2. Interestingly, in a screen of 398 patients with AML, TET2 and IDH2 mutations were mutually exclusive, suggesting that these two mutations have a similar function. Wild type TET2 demethylates DNA, and mutations in TET2 lead to increases in 5-methylcytosine similar to those seen in patients with IDH mutations. It has been suggested that elevated levels of 2-HG caused by mutant IDH2 act to inhibit wild type TET2 function (8). The mechanism of action of mutant IDH2 is detailed in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Mutant IDH2 leads to a block in cellular differentiation.

Hypermethylation of target genes blocks cellular differentiation. The stable expression of IDH2 mutant genes in murine bone marrow cells leads to an increase in the proportion of immature myeloid precursors as assessed by morphology and evaluation of mature myeloid cell surface markers (9). Similarly, 2-HG elevation in adipocytes and astrocytes leads to an increase in repressive histone methylation marks and a subsequent block in differentiation (10). Mutant IDH2 produces a similar degree of hypermethylation, elevated levels of 2-HG, and the generation of undifferentiated sarcomas in-vivo (11). Treatment with hypomethylating agents reverses the differentiation block seen in these cells.

Small molecule inhibitors of mutant IDH2 were developed to decrease levels of 2-HG and reverse the block in cellular differentiation. Screening of a small-molecule library using an enzyme assay in the presence of saturating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) identified a series of heterocyclic urea sulfonamides as inhibitors of IDH2/R140Q. AGI-6780 (Agios Pharmaceuticals), is a compound with slow-tight binding and non-competitive inhibitory properties. Medicinal chemistry optimization of the urea sulfonamide led to the design of AGI-6780, a molecule with nanomolar potency for 2HG inhibition and long residence time (kon = 5.8 Å∼ 104M−1 min−1; koff = 8.3 Å∼ 10−3 min−1). Primary human AML cells with an IDH2 mutation grown ex-vivo were cultured in the presence or absence of AGI-6780. A burst of cellular differentiation was seen starting at day 4 in the cells treated with AGI-6780 with a decrease in myeloblasts and increase in mature monocytes and granulocytes as assessed immunophenotypically by flow cytometric analysis (9). Additional analyses of 2-HG levels and methylation status in TF1 cells with an IDH2 R140Q mutation demonstrated that the addition of AGI-6780 reversed the hypermethylation phenotype and lowered the levels of 2-HG (12).

Hematologic Malignancies and IDH2 Mutations

Because IDH2 mutations are most commonly found in patients with hematologic malignancies, and because AML is a more common malignancy than AITL, most of the lab-based research and retrospective series have looked at IDH2 mutations in AML. Mutations in IDH2 occur at a higher frequency in AML than in myelodysplastic syndromes and myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN)(13, 14).

In AML, IDH2 R140 mutations occur in approximately 80% of patients as compared to IDH2 R172 mutations that occur in only 20%. IDH2 mutations are enriched in patients with cytogenetically normal AML, but approximately 20-30% of patients with IDH2 mutations have an abnormal karyotype, most commonly in the intermediate or unfavorable risk cytogenetic subgroups (15). In retrospective studies, the prognosis of patients with IDH2 mutations treated with induction chemotherapy is controversial (15-20). The discrepant results may be related to the methodology of the analyses. Some studies combined the analyses of patients with IDH1 and IDH2 mutations while others looked at IDH2 mutant patients alone. Other studies analyze patients with IDH2 R140 and R172 together. The Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB – now renamed the Alliance) found that 69 out of 358 patients (19%) treated on of CALGB trials had a mutation in IDH2, with 81% being mutations in R140 and 19% in R172. There were stark differences in CR and overall survival between patients with an R172 and an R140 mutation; 70% of patients with an R140 mutation achieved a CR compared to only 38% of patients with an R172 mutation (17). The difference in outcomes between patients with an R140 and R172 was confirmed in a separate retrospective study performed by the UK MRC (18). In this study, the CR rate was 88% in the R140 patients and only 48% in those with an R172. The cumulative incidence of relapse was a 70% in patients with R172 compared to 28% in patients with an R140 mutation and the combined decreased CR rate and increased rate of relapse in R172 patients translated into a five year overall survival of 27% compared to 57% in R140 patients. The biologic basis for these differences remain to be fully elucidated but may be related to other mutations that co-occur with R172 or R140 that make patients chemo-resistant.

Clinical characteristics of patients with R172 mutations differ from those with R140 mutations. The presenting white blood count in patients with R172 is generally lower than those with R140 and they are more likely to have an intermediate risk karyotype (15).

The frequency of IDH2 mutations in AML increases with age (15). There are no published data on the outcomes of older patients treated with IDH2 mutations treated with hypomethylating agents or low dose ara-C.

The oncometabolite 2-HG has been explored both retrospectively and prospectively as a biomarker of IDH mutant AML, and of response to therapy. In a retrospective analysis, researchers from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) found that, the sensitivity and specificity of measuring 2-HG (using a cutoff of 700-ng/mL) was 86.9% and 90.7%, respectively for IDH1 or IDH2 mutant AML (21). Expanding on these results, Fathi and colleagues measured serum 2-HG levels prospectively in patients with IDH mutations and found that pre-treatment 2-HG levels predicted the presence of an IDH mutation at diagnosis. Decreases in 2-HG, which could be measured in blood and urine, correlated with response to therapy (22).

AITL and IDH2

AITL is a rare peripheral T cell lymphoma affecting approximately 1-2% of patients with non-hodgkins lymphoma (NHL) per year in the United States. Genotyping of archived NHL samples from the Tenomic Consortium and the University of Hong Kong, revealed that 20% of patient samples with AITL, had a mutation in IDH2 (primarily R172). Subsequent confirmation of this finding by genotyping 22 additional banked lymphoma samples from a different center demonstrated that 45% of patients had an IDH2 R172 mutation (4). In addition a subsequent study looking at the genomic landscape of AITL in 85 patients from four academic medical centers in the United States and Europe showed that 20% of the patients had a mutation in IDH2 R172 (23).

Clinical-Translational Advances

It is somewhat remarkable that in the short time since mutations in IDH2 were discovered in 2009, AG-221, a reversible inhibitor of mutant IDH-2, has been introduced into phase 1 clinical trials for patients with AML and AITL/solid tumors (NCT01915498, NCT02273739). To date, interim results have been presented for patients with AML with the last update given at the annual meeting of the European Hematology Association in June, 2015 (24). The ongoing results of this study are remarkable for what they teach us about the efficacy of inhibiting mutant IDH2 as well as the questions they raise for the therapeutic treatment of AML. As of May 1, 2015, 177 patients in dose escalation and dose expansion cohorts with relapsed/refractory AML, untreated AML, MDS or other myeloid malignancies (CMML, myeloid sarcoma) have been treated. Consistent with pre-clinical models, inhibition of mutant IDH2 leads to dramatic decreases in both plasma and bone marrow 2-HG to baseline levels that are seen in healthy volunteers. 2-HG is inhibited up to 98% in patients with R140Q mutations and in up to 88% of patients with R172K mutations. Although AG-221 is more potent against R140Q mutations, this does not translate into changes in efficacy in R172 mutated patients.

Of the 158 patients who received at least one dose of drug and either discontinued the study before day 28 (for any reason) or have a day 28 response assessment, the ongoing overall response rate is 40% with 16.5% achieving a true complete remission with morphologic clearance of myeloblasts from the bone marrow and restoration of normal neutrophil and platelet counts. The subset of patients with relapsed and refractory AML had a CR rate of 21.7%. An additional 12% of patients had clearance of myeloblasts from the marrow with various degrees of hematologic recovery. The composite complete remission rate (CRc – including CR, CRp, CRi and morphologic CR) among all R/R AML patients is 28.6%. A substantial subset of the patients treated had a true partial remission (PR) with decrease of myeloblasts by 50% to between 5-25% of total marrow cellularity and more importantly, restoration of normal hematopoiesis. An additional 43% of patients had “stable disease,” until now a category little used in the assessment of responses in patients with AML. Some of these stable disease patients normalize both their platelet and neutrophil counts, despite persistence of myeloblasts in the bone marrow. In the data presented at EHA many of these patients with both stable disease and PR remain on study for as long as patients with complete remission, suggesting that the traditional conception of AML patients needing to achieve a CR in order to have an overall survival benefit may need to be reassessed.

Areas for Further Investigation

While preliminary data exists for patients with AML and other myeloid malignancies, the efficacy of IDH2 inhibition in AITL and solid tumors is not yet reported. To date, inhibition of mutant IDH2 has led to remarkable results for patients with IDH2 mutant relapsed or refractory AML. Perhaps most striking is the dramatically low rate of primary progressive disease in patients treated with AG-221. In those patients who achieve a CR by traditional international working group (IWG) criteria, the depth of remission – whether patients have immunophenotypic or molecular residual disease at the time of CR remains unknown. This has potential implications for duration of therapy. That is, does inhibition of mutant IDH2 truly cure AML, such that physicians can stop treatment or does inhibition of mutant IDH transform AML into a chronic leukemia? While patients who have true partial remissions likely have clinical benefit (transfusion independence, decreased rates of febrile neutropenia and hospital admission) the large number of patients with “stable disease” who remain on trial for a prolonged period of time need detailed analysis. Some of these patients may have normalization in their hematologic parameters – consistent with ongoing differentiation of leukemic myeloblasts – but no decrease in blasts. In addition, whether the dramatic results seen in relapsed and refractory AML translate to patients with IDH2 mutant positive AITL and solid tumors remains to be seen.

Mutant IDH2 recapitulates Warburg's original hypothesis of altered cellular metabolism as a crucial difference between normal and malignant cells. The rise in 2-HG that leads to downstream hypermethylation of target genes and blocks cellular differentiation, is clearly reversible with small molecule inhibition in the laboratory and early results from a phase 1 clinical trial in relapsed and refractory AML, demonstrate proof of concept that decreasing 2-HG, allows malignant myeloblasts to differentiate into adult neutrophils.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: E.M. Stein is a consultant/advisory board member for Agios Pharmaceuticals. No other potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Yuan W, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:765–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amary MF, Bacsi K, Maggiani F, Damato S, Halai D, Berisha F, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent events in central chondrosarcoma and central and periosteal chondromas but not in other mesenchymal tumours. J Pathol. 2011;224:334–43. doi: 10.1002/path.2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cairns RA, Iqbal J, Lemonnier F, Kucuk C, de Leval L, Jais JP, et al. IDH2 mutations are frequent in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2012;119:1901–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-391748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borger DR, Tanabe KK, Fan KC, Lopez HU, Fantin VR, Straley KS, et al. Frequent mutation of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)1 and IDH2 in cholangiocarcinoma identified through broad-based tumor genotyping. Oncologist. 2012;17:72–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gross S, Cairns RA, Minden MD, Driggers EM, Bittinger MA, Jang HG, et al. Cancer-associated metabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate accumulates in acute myelogenous leukemia with isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 mutations. J Exp Med. 2010;207:339–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward PS, Patel J, Wise DR, Abdel-Wahab O, Bennett BD, Coller HA, et al. The common feature of leukemia-associated IDH1 and IDH2 mutations is a neomorphic enzyme activity converting alpha-ketoglutarate to 2-hydroxyglutarate. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:225–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figueroa ME, Abdel-Wahab O, Lu C, Ward PS, Patel J, Shih A, et al. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:553–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang F, Travins J, DeLaBarre B, Penard-Lacronique V, Schalm S, Hansen E, et al. Targeted inhibition of mutant IDH2 in leukemia cells induces cellular differentiation. Science. 2013;340:622–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1234769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu C, Ward PS, Kapoor GS, Rohle D, Turcan S, Abdel-Wahab O, et al. IDH mutation impairs histone demethylation and results in a block to cell differentiation. Nature. 2012;483:474–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu C, Venneti S, Akalin A, Fang F, Ward PS, Dematteo RG, et al. Induction of sarcomas by mutant IDH2. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1986–98. doi: 10.1101/gad.226753.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kernytsky A, Wang F, Hansen E, Schalm S, Straley K, Gliser C, et al. IDH2 mutation-induced histone and DNA hypermethylation is progressively reversed by small-molecule inhibition. Blood. 2015;125:296–303. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-533604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Abdel-Wahab O, Guglielmelli P, Patel J, Caramazza D, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutation studies in 1473 patients with chronic-, fibrotic- or blast-phase essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera or myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2010;24:1302–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosmider O, Gelsi-Boyer V, Slama L, Dreyfus F, Beyne-Rauzy O, Quesnel B, et al. Mutations of IDH1 and IDH2 genes in early and accelerated phases of myelodysplastic syndromes and MDS/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2010;24:1094–6. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paschka P, Schlenk RF, Gaidzik VI, Habdank M, Kronke J, Bullinger L, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent genetic alterations in acute myeloid leukemia and confer adverse prognosis in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia with NPM1 mutation without FLT3 internal tandem duplication. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3636–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.3762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boissel N, Nibourel O, Renneville A, Gardin C, Reman O, Contentin N, et al. Prognostic impact of isocitrate dehydrogenase enzyme isoforms 1 and 2 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: a study by the Acute Leukemia French Association group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3717–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcucci G, Maharry K, Wu YZ, Radmacher MD, Mrozek K, Margeson D, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 gene mutations identify novel molecular subsets within de novo cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2348–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green CL, Evans CM, Zhao L, Hills RK, Burnett AK, Linch DC, et al. The prognostic significance of IDH2 mutations in AML depends on the location of the mutation. Blood. 2011;118:409–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-322479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janin M, Mylonas E, Saada V, Micol JB, Renneville A, Quivoron C, et al. Serum 2-hydroxyglutarate production in IDH1- and IDH2-mutated de novo acute myeloid leukemia: a study by the Acute Leukemia French Association group. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:297–305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel JP, Gonen M, Figueroa ME, Fernandez H, Sun Z, Racevskis J, et al. Prognostic relevance of integrated genetic profiling in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1079–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiNardo CD, Propert KJ, Loren AW, Paietta E, Sun Z, Levine RL, et al. Serum 2-hydroxyglutarate levels predict isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations and clinical outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;121:4917–24. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-493197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fathi AT, Sadrzadeh H, Borger DR, Ballen KK, Amrein PC, Attar EC, et al. Prospective serial evaluation of 2-hydroxyglutarate, during treatment of newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia, to assess disease activity and therapeutic response. Blood. 2012;120:4649–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-438267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Odejide O, Weigert O, Lane AA, Toscano D, Lunning MA, Kopp N, et al. A targeted mutational landscape of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2014;123:1293–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-531509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiNardo CS, Stein EM, Altman JK, Collins R, DeAngelo D, Fathi AT, et al. AG-221, an oral, selective, first-in-class, potent inhibitor of the IDH2 mutant enzyme, induced durable responses in a phase 1 study of IDH2 mutation-positive advanced hematologic malignancies [abstract]. Proceedings of the EHA 20th Congress; 2015 Jun 11-15; Vienna, Austria. The Hague (The Netherlands): European Hematology Association; Abstract nr P569. [Google Scholar]