Abstract

Infection by the human pathogen Legionella pneumophila relies on the translocation of ~300 virulence proteins, termed effectors, which manipulate host-cell processes. However, almost no information exists regarding effectors in other Legionella pathogens. Here we sequenced, assembled and characterized the genomes of 38 Legionella species, and predicted their effector repertoire using a previously validated machine-learning approach. This analysis revealed a treasure trove of 5,885 predicted effectors. The effector repertoire of different Legionella species was found to be largely non-overlapping, and only seven core-effectors were shared among all species studied. Species-specific effectors had atypically low GC content, suggesting exogenous acquisition, possibly from their natural protozoan hosts. Furthermore, we detected numerous novel conserved effector domains, and discovered new domain combinations, which allowed inferring yet undescribed effector functions. The effector collection and network of domain architectures described here can serve as a roadmap for future studies of effector function and evolution.

Several bacterial pathogens, such as the agents of tuberculosis, typhus, typhoid fever, Q-fever, and Legionnaires' disease manipulate numerous processes in human cells, involving hundreds of proteins. In many pathogens this is achieved by specialized secretion systems that translocate into the host's cytoplasm a cohort of proteins, termed effectors, which modulate host-cell processes. One such pathogen is Legionella pneumophila, the causative agent of Legionnaires' disease. These bacteria multiply in nature in a broad range of free-living amoebae1, and cause pneumonia in humans when contaminated water aerosols are inhaled2. Besides L. pneumophila, more than 50 Legionella species have been identified, and at least 20 were associated with human disease3.

Following uptake of L. pneumophila by macrophages or protozoa, the bacteria are compartmentalized within a specialized vacuole, the Legionella containing vacuole (LCV), which does not fuse with lysosomes and does not acidify4. The LCV associates with endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-derived secretory vesicles, mitochondria, and rough ER5, followed by bacterial replication inside an ER-like organelle6. Little is known about the intracellular lifestyle of other Legionella species.

The major pathogenesis system of L. pneumophila is composed from a group of 25 proteins called Icm (intracellular multiplication) or Dot (defect in organelle trafficking), which constitute a type-IV secretion system7,8. Type-IV secretion systems are macromolecular devices, evolutionary related to bacterial conjugation systems, which translocate effector proteins into host cells9. All the Legionella species studied to date harbor a type-IVB Icm/Dot secretion system10, which is required for intracellular growth11. This secretion system was also found in Coxiella burnetii, the etiological agent of Q-fever, where it is also required for intracellular growth12,13, and in the arthropod pathogen Rickettsiella grylli14

To date, approximately 300 L. pneumophila effector proteins have been experimentally shown to translocate into host cells via the Icm/Dot secretion system. However, single deletion of effector-coding genes rarely causes a detectable defect in intracellular growth15. This is commonly explained by functional redundancy: multiple effectors that perform similar functions, effectors that target different steps of the same host-cell pathway, and effectors that manipulate parallel pathways16. Notably, only very few Icm/Dot effectors have been identified in other Legionella species. The pool of effectors of each species is believed to orchestrate its intracellular lifestyle. Effectors present in different Legionella species might modulate different host-cell pathways, and most likely possess biochemical functions not present in L. pneumophila effectors.

Sequencing de novo of 38 Legionella species allowed us to explore the universe of effectors that arm the Legionella genus, study the evolution of these special proteins, and identify new potential functions mediated by them.

RESULTS

Sequencing, assembly, phylogeny, and genomic characterization

We sequenced the genomes of isolates from 38 different Legionella species (Supplementary Table 1). The assembled genomes were highly covered with a median coverage of 606x. The number of contigs ranged between 12 and 154, and the median N50 for the 38 genomes was 386kbp, with eight genomes having N50 > 1.4Mbp (see Supplementary Table 2 for details). Protein-coding genes were predicted and clustered into 16,416 orthologous groups, out of which 1,054 orthologs were present in all 41 genomes analyzed. We designated these groups as LOGs for Legionella Orthologous Groups (Supplementary Table 3). Genome completeness was assessed using a set of 55 single copy genes, which were found in all but two genomes that missed a single gene each (see Methods, and Supplementary Table 4).

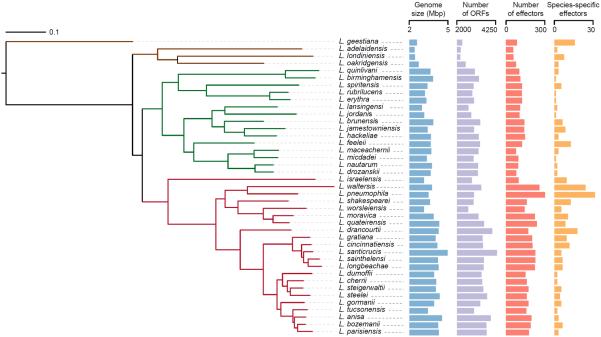

The reconstructed phylogenetic tree suggests a clear divergence among three major clades (Fig. 1): (1) a clade containing 22 species (marked in dark red in Fig. 1) including the best-studied Legionella pathogens: L. pneumophila, L. longbeachae, L. bozemanii, and L. dumoffii, responsible together for more than 97.8% of human Legionella infection cases17; (2) Another major clade, characterized by long branches, that encompasses 15 Legionella species including L. micdadei (marked in dark green in Fig. 1); (3) A deep-branching clade consisting of L. oakridgensis, L. londiniensis, and L. adelaidensis (marked in brown in Fig.1). Finally, as previously reported18, L. geestiana is an out-group to the rest of Legionella genus (based on tree rooting using C. burnetii).

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree of the Legionella genus.

A maximum-likelihood tree of 41 sequenced Legionella species was reconstructed based on concatenated amino-acid alignment of 78 orthologous ORFs. For each species the following are also illustrated: genome sizes (blue), number of ORFs (purple), number of effectors (red), and number of unique effectors (orange). The evolutionary dynamics in general, and specifically of effectors, differ between the two major clades (marked in dark red and dark green), and between these and the deep-branching clade (marked in brown). Bootstrap values are presented as part of Supplementary Figure 4.

The length of the reconstructed genomes ranged from 2.37 Mbps in L. adelaidensis to 4.82 Mbps in L. santicrucis (Fig. 1). Notably, the deep branching clade is characterized by species with significantly smaller genomes compared the rest of the species (p-value 2.3×10−8, one-sided t-test). To ensure that the observed variation in genome size was not due to assembly quality or coverage, we tested for correlation of genome size with coverage, N50, and number of assembled contigs. None of these presented significant correlation with genome lengths (Supplementary Table 2). The GC content of the genomes was highly variable, ranging from 36.7% in L. santicrucis to 51.1% in L. geestiana. Five species (L. quinlivanii, L. birminghamensis, L. spiritensis, L. erythra and L. rubrilucens) with significantly high GC content (43.0% – 47.7%, p-value 0.0004, one-sided Wilcoxon test compared to the GC content of the rest of the genomes) formed a monophyletic group. Other high GC species were spread across the Legionella tree (Supplementary Table 5).

The Icm/Dot secretion system

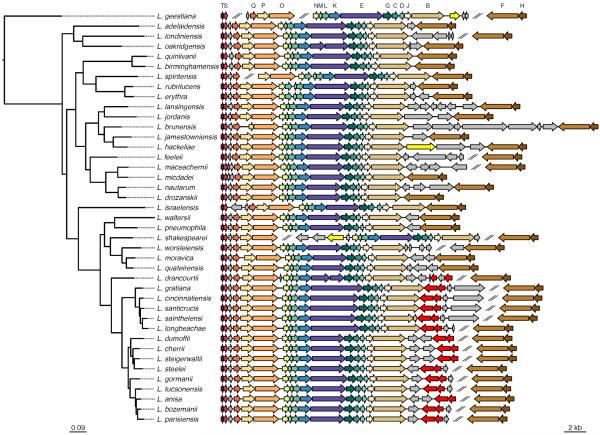

The Icm/Dot type-IV secretion system is the major pathogenesis system of L. pneumophila. The system components are encoded by 25 genes that are organized in two separate genomic regions on the genome. Region I contains seven genes, and region II contains 18 genes19.

The availability of the 41 Legionella genomes made it possible to obtain a comprehensive view of the genomic organization of the icm/dot genes. In both Icm/Dot regions, the order and orientation of the genes were perfectly conserved throughout the genus (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The main differences in the organization were in gene insertions of variable size that seem to be unrelated to the Icm/Dot secretion system. For example, an insertion of seven genes between icmB and icmF in L. brunensi, compared to a single gene between the same two genes in L. pneumophila, and no intervening gene in L. quinlivanii). In 15 Legionella species an OmpR-family two-component regulatory system is encoded next to the icmB gene, the last gene in the large sub-region of region II. These 15 species are monophyletic (Fig. 2), suggesting this regulatory system was acquired once and was preserved since. Similarly, thirteen species contained an effector-encoding gene (a legA15 homolog, marked in orange in Supplementary Fig. 1) between the two sub-regions of region I. These species also form a monophyletic clade together with L. gormanii, in which this effector is missing, indicating that the LegA15 homolog was probably acquired once in the common ancestor of the species in this clade, and subsequently loss in the lineage leading to L. gormanii. Notably, the locations of the gene insertions were also highly conserved across all the sequenced species, indicating tight co-regulation within sub-regions comprising of the sets of genes that were not separated throughout the genus.

Figure 2. Icm/Dot secretion system region II in 41 Legionella species.

In 15 genomes, genes coding for an OmpR-family two-component system were found (bright red). In three other genomes putative effectors were found in Region II (bright yellow). Genes colored in grey represent non-effector genes found between the two parts of the region. Icm/Dot genes symbols: T: icmT, S: icmS, R: icmR, Q: icmQ, P: icmP/dotM, O: icmO/dotL, N: icmN/dotK, M: icmM/dotJ, L: icmL/dotI, K: icmK/dotH, E: icmE/dotG, G: icmG/dotF, C: icmC/dotE, D: icmD/dotP, J: icmJ/dotN, B: icmB/dotO, F: icmF and H: icmH/dotU. A similar analysis of region I is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1).

The Legionella genus effector repertoire

The L. pneumophila Icm/Dot type-IV secretion system translocates a large cohort of approximately 300 effector proteins20,21. In order to predict novel effectors in all available Legionella genomes, we first identified in each species proteins highly similar to experimentally validated Legionella effectors. These served as training sets for a machine-learning procedure that we previously developed, and proved its high precision rates using experimental validations22,23. The machine-learning procedure takes into account various aspects of the effectors in the training set, including regulatory information, existence of eukaryotic motifs, the Icm/Dot secretion signal, and similarity to known effectors and host proteins. The predictions were performed for each genome separately, enabling the recognition of patterns unique to individual Legionella species (Supplementary Fig. 1).

The number of putative effectors was highly variable: from 52 in L. adelaidensis to 247 in L. waltersii (Fig. 1). Species in different clades of the Legionella tree significantly differ in the number of predicted effector-coding genes, even when accounting for the variance in the genome size (ANOVA p-value 2.77×10−6, see Methods). The species from the deep branching clade contained an average of 59 effectors, compared to an average of 107 the major “L. micdadei clade” and 183 on average in the “L. pneumophila clade”. In total, we identified in the Legionella genus a set of 5,885 putative effectors.

The training set used to identify effectors was based almost exclusively on L. pneumophila effectors. Therefore, we can expect a certain bias towards effectors with characteristics similar to L. pneumophila's effectors. To assess the strength of such a bias we compared the number of predicted effectors to the number of effectors with Icm/Dot translocation signal, which was shown to be present in effectors from different Legionella species, and even in effectors from C. burnetii23. The results show a strong and significant correlation between the number of effectors and the number of proteins bearing a translocation signal across all the species (p-value 1.004×10−13, R2 = 0.76, Pearson correlation, see Supplementary Fig. 3). Further, no significant correlation was found between the evolutionary distance from L. pneumophila and the ratio between predicted effectors and proteins with translocation signal (Supplementary Fig. 3). We conclude that no significant bias towards preferential effector identification in species closer to L. pneumophila was detected.

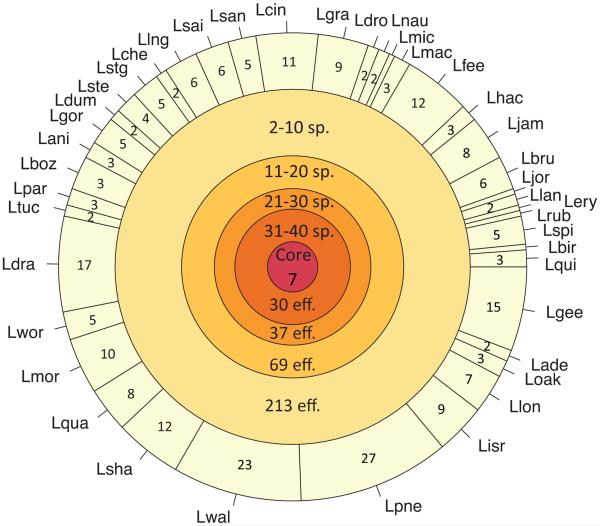

Orthologous groups of Legionella genes that consisted of ≥ 80% predicted effectors were designated Legionella effectors ortholog groups (LEOGs). We identified 608 LEOGs, and found that most effectors were shared by a small subset of species. Surprisingly, only seven orthologs were “core effectors”, i.e. had orthologs in every Legionella genome analyzed (Fig. 3). Notably, about 63% (3,715 effectors in 269 LEOGs) of the effector repertoire consisted of orthologs of experimentally validated effectors from L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae. The rest, 2,170 effectors in 339 LEOGs represented new putative effectors, potentially with novel functionality.

Figure 3. Extent of effector sharing by the Legionella species studied.

Circles represent sets of effectors share by different number of Legionella species. The number of species in which these effectors were found is indicated in the top of the circles, and the number of effectors contained in the set is marked on the bottom. The innermost circle represents the set of core effectors shared by all Legionella species studied. The outermost circle depicts the 258 species-specific effectors, and is sliced based on the number of species-specific effectors found in each Legionella species. Notably, only seven effectors were shared among all Legionella species, and most effectors (78.5%) are shared by less than ten species (two outermost circles).

We identified 15 cases of clear effector pseudogenization due to nonsense mutations (see Methods, and Supplementary Table 6). Our results suggest some species are more prone to pseudogenization than others. For example, five pseudogenes in L. anisa and L. bozemanii were homologous to complete genes in L. steelei, but no pseudogene was identified in L. steelei itself. Effectors pseudogenization does not have to result with a non-functional protein, this process might be part of effectors evolution that leads to diversification, as was previously suggested for effectors in C. burnetii13.

The high number of effectors predicted in the Legionella genus allowed us, for the first time, to perform genomic analyses on this extraordinary group of genes. These analyses resulted in intriguing observations regarding the distribution, function and evolution of the Legionella genus effector repertoire, as described below.

The seven core-effectors of the Legionella genus

In light of the high number of LEOGs found, the identification of only seven core effectors in the Legionella genus was surprising. Comparison of the evolutionary trees of each core effector to the species tree (Supplementary Fig. 4) revealed that, excluding LOG_01106, the core effector trees do not differ significantly from the species tree (AU-test24 p-value < 0.01 after False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction for multiple testing25, see Methods). Close examination of the phylogeny of LOG_01106 revealed that in general the evolution of this effector agrees with the species tree, and the disagreeing splits are not well supported (based on bootstrap values, see Supplementary Fig. 4). Further, while all core effectors are highly similar at the protein level, their GC content is variable and very similar to the average genomic GC content of each species (Supplementary Table 5). Combined, these findings suggest that these core effectors evolved as part of the Legionella genus for an extended period of time.

Remarkably, only a single core effector (LOG_00212 represented in L. pneumophila by lpg2300 - LegA3) was found in all the bacteria known to harbor an Icm/Dot secretion system. This effector was found in all the Legionella species examined, as well as in C. burnetii (CBU_1292) and R. grylli (RICGR_1042). The homologues in these bacteria share high degree of similarity with their L. pneumophila counterpart throughout the length of the protein (BLAST E-values of 2×10−116 and 3×10−120, respectively). All the members of this LOG contain a single ankyrin repeat at their N-termini. Ankyrin repeats are usually found in eukaryotic proteins where they mediate protein-protein interactions in a wide range of protein families26,27.

An additional core effector (LOG_00334 represented in L. pneumophila by lpg2815 - MavN) was also found in R. grylli (RICGR_0048). The L. pneumophila MavN was recently found to be strongly induced in iron-restricted conditions. Mutants lacking this gene were defective for growth on iron-depleted solid media, defective for ferrous iron uptake, and impaired in intracellular growth within their environmental host Acanthamoeba castellanii28,29. These findings suggest that this effector might be involved in iron acquisition during intracellular growth within the iron-poor milieu of the LCV.

The other five core effectors were not found in either C. burnetii or R. grylli, but two of these core effectors (LOG_00341 and LOG_01049 represented in L. pneumophila by lpg2832 and lpg0107-RavC, respectively) had homologues in more distant bacteria. Lpg2832 has homologous proteins in several Rhizobiales such as Bradyrhizobium (BLAST E-value 1×10−22). These are symbionts of leguminous plants that fix atmospheric nitrogen, and utilize a type-IVA secretion system for symbiosis30,31. The second ortholog group with homologues outside of the Legionella genus is represented in L. pneumophila by lpg0107-RavC, and has homologues in several members of the Chlamydiae phylum, such as Diplorickettsia massiliensis (E-value 2×10−49), Protochlamydia amoebophila (E-value 2×10−34) and Chlamydia trachomatis (E-value 3×10−31). All these bacteria are intracellular human pathogens that utilize a type-III secretion system for intracellular growth. The presence of these two effectors in evolutionary distant species could be the result of cross-genera HGT, or alternatively these genes might have existed in a common ancestor and lost in the lineages lacking them. We tested these alternative hypotheses by comparing two models representing these evolutionary scenarios (see Methods), and conclude that these effectors have been horizontally transferred across genera (p-value 3.2×10−35 for LOG_00341, 3.4×10−61 for LOG_01049; likelihood-ratio test) and were adapted in different pathogens to different secretion systems.

To obtain a first indication regarding the importance of these seven core-effectors, single deletion substitution mutants were constructed in L. pneumophila, and tested for intracellular growth in A. castellanii (a known L. pneumophila environmental host). The result indicated that LegA3 and MavN are partially required for intracellular growth in this host (Supplementary Fig. 5), a phenotype that was completely complemented when the effector was introduced on a plasmid. To conclude, while the exact function of these seven Legionella genus core-effectors is still unknown, their high conservation throughout the evolution of the Legionella genus, and in some cases beyond, strongly suggests that they perform critical functions during infection. The fact that only two of the core effectors showed an intracellular growth phenotype suggests that the function of the other core effectors may be redundant, at least for intracellular growth in A. castellanii. It is possible, however, that the core effectors carry out essential functions required for the growth in other hosts.

Effector Synteny and co-evolution

Effector-coding genes residing in close proximity on the genome have been shown in some cases to function together in the host cell32,33. We hence searched for effectors that are consistently found together (within 5 ORFs of each other) across multiple genomes. We found 143 pairs of effectors that were found in close proximity in at least two genomes, out of which 51 pairs were found in five genomes or more. Supplementary Table 7 details the syntenic genes and their organization in each genome. We further analyzed which of these pairs display statistically significant coevolution, i.e., syntenic effectors that were gained and lost together during the genus evolution (see Methods). The combined analysis revealed 19 pairs of effectors that are syntenic and coevolve (Supplementary Table 7), some of which are already known to have related function. For example, AnkX (LOG_03154) and Lem3 (LOG_032115) both modulate the host GTPase Rab134 (counteracting each other). Similarly, SidH (LOG_04780) and LubX (LOG_06016) were also shown to function together35. Recently it was reported that SidJ affects the localization and toxicity of effectors from the SidE family36,37, here we found that SdjA (SidJ paralog, LOG_04652) was consistently found next to SdeD (SidE paralog, LOG_04652) in all six genomes where both of them were present, and SdeC (another SidE paralog) was found next to SidJ in five of the six genomes that encoded both effectors. These results led us to examine additional syntenic effectors that co-evolve. We found five such pairs of effectors in L. pneumophila (SidL-LegA11, Lpg2888-MavP, SidI-Lpg2505, Ceg3-Lpg0081 and CetLp7- Lem29) that were not previously described to function as pairs. Notably, two of these effectors (SidL and SidI, found in different pairs) inhibit translation by interacting with the translation initiation factor eEF1A, and inhibit yeast growth38,39. The LegA11 and Lpg2505 effectors might counteract the activity of SidL and SidI correspondingly (as in the AnkX-Lem3, and SidH-LubX pairs), since the translational block mediated by SidL and SidI early during L. pneumophila infection should be removed in order to enable a successful infection.

Unique effectors in the Legionella genus

The analysis of the LEOGs revealed that 258 of them (42%) are species-specific, meaning that they were observed in only one of the Legionella species analyzed. Excluding L. pneumophila, the species with the highest number of unique putative effectors is L. waltersii, with 23 species-specific effectors. Notably, every genome analyzed had at least a single species-specific effector (Fig. 1). The GC content of these effectors is consistently lower than the genomic GC content (Supplementary Table 4), suggesting these genes might have been recently acquired from exogenous source, possibly from the natural protozoan hosts of Legionella, which are typically characterized by low GC content40.

The 258 species-specific LEOGs include 70 putative effectors that have no local similarity to any other protein in the Legionella genomes analyzed (for BLAST E-value < 1×10−4). Of these 70 unique putative effectors, only five had significant similarity to any known protein (E-value < 1×10−4, BLAST search against NCBI's non-redundant database). Four unique effectors were similar to proteins encoded in various bacteria (Supplementary Table 8) from different ecosystems, but one of the unique effectors (Lmac_0005) was similar to a hypothetical protein from Candidatus Protochlamydia amoebophila, an endosymbiont of Acanthamoeba41. This hit is not highly significant (E-value 3.09×10−6), yet it might be the result of horizontal gene transfer (HGT) occurring inside a common protozoan host. Despite having no similarity to any Legionella protein, 23 of the 70 unique putative effectors contain regulatory elements highly similar to binding sites of transcription factors associated with pathogenesis (CpxR and PmrA)42,43, and 28 had C-terminal amino-acid profile indicative of Icm/Dot secretion signal20. Further, for 11 unique effectors we identified domains known to be encoded by effectors, and 53 had at least one additional effector encoded in their vicinity (Supplementary Table 8). Combined, for 62 of the 70 unique effectors we could find sequenced-based support that these unique proteins are indeed genuine effectors. The fact that none of them had significant sequence similarity to another Legionella-encoded protein demonstrates the magnitude of the functional novelty of putative effectors found in the genome analyzed. The low GC content of species-specific effectors combined with the fact that most of them contain an Icm/Dot-associated regulatory element or an Icm/Dot secretion signal, suggest that recently acquired genes can be adapted to function as effectors in a relatively short evolutionary time.

Variability in the frequency in which different Legionella species acquire and lose effectors

To gain insights into the evolutionary processes that shape the current effector repertoire of each Legionella species, we examined the dynamics of effector gain and loss along the phylogenetic tree. The results of this analysis are displayed in Supplementary Figure 6. The results of this analysis demonstrate that the rate of acquirement and loss of effectors in the “L. micdadei clade” is significantly lower compared to the “L. pneumophila clade” (p-value 1.4×10−10, one-sided Wilcoxon test), i.e., the latter has a more dynamic repertoire of effectors. This is in agreement with the number of unique LEOGs found in the different Legionella species (Fig. 1). Collectively, these analyses suggest that certain Legionella species, including the most pathogenic species of the genus, acquire genetic information from outside of the Legionella genus more frequently than others, and adapt it to function as effector proteins.

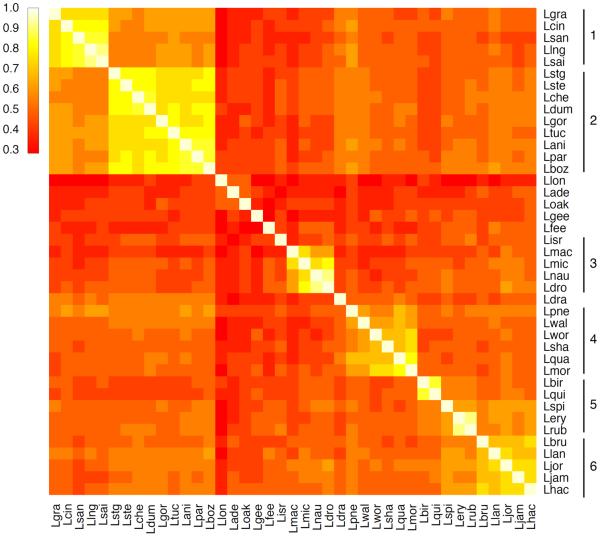

Effector gene repertoire is dictated predominantly by phylogenetic distance

The numerous HGT events discovered in the effector gain-loss analysis, led us to search for patterns, other than the phylogenetic relationships, that would explain the variable effector repertoires in the different Legionella species. To address this, we compared the effector gene repertoires by calculating the fraction of shared effectors between each two species, and then clustered species based on the similarities in their effector pool (Fig. 4). The emergent clusters strongly agree with the phylogenetic relationships: we could match these effector-based clusters to monophyletic clades of the Legionella species tree (marked by number on the right of Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 6). Further, the organization among these clusters mostly agreed with the phylogeny as well. This pattern could arise either by HGT events with no consistent directionality among Legionella species, or by preferential transfer between closely related species. To test which of these is more dominant we reconstructed the phylogenies of 96 effectors that underwent HGT and compared them to the species tree (see Methods). In the majority of cases (62.5%), there was no significant difference between the placement of the genes in the effector tree and the placement of the species bearing them in the species tree (see Supplementary Fig. 7). These results suggest that the HGT events that these effectors underwent were preferentially among closely related species, which explains, to a large extent, the observed agreement between effector sets and the phylogenetic clustering of the species.

Figure 4. Comparison of the putative effector pools among Legionella species.

Color gradient represent similarity between sets of effectors (light colors for high similarity). Clusters defined based on similar effector repertoires (marked on the right) are in agreement with the clades of the phylogenetic tree (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Domain shuffling plays a major role in effector evolution

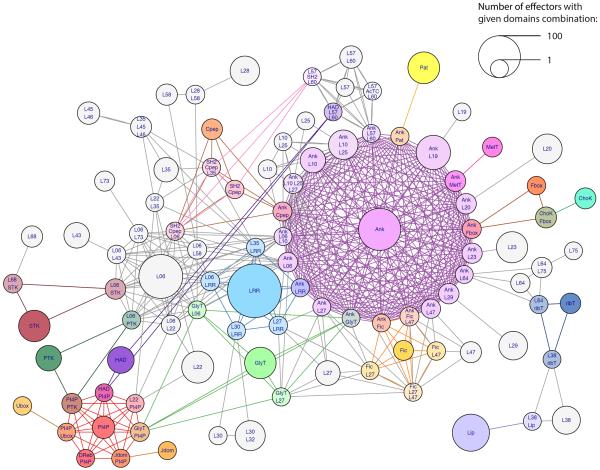

Previous studies of L. pneumophila effectors revealed that they harbor numerous eukaryotic domains44,45 as well as effector-specific domains46,47. The high number of effectors we found made it possible to identify and analyze conserved effectors domains across the genus. We identified Legionella Effector Domains (LEDs) using two methods: (1) similarity to known domain databases, and (2) conservation of regions among the Legionella effectors across orthologous groups (see Methods). Conserved domains were detected in 56% of the putative effectors. Overall, 99 distinct domains were identified by the two methods combined: 53 well-characterized (mostly eukaryotic) domains from existing databases were found in 1,335 putative effectors from 186 LEOGs; and 46 new conserved domains that are reported here for the first time were found in 1,458 putative effectors from 178 different LEOGs (a complete list of the domains identified is detailed in Supplementary Table 9). Analyzing the protein architectures (different domain combinations), we noticed that the same domains were often shared among different architectures. We visualized this phenomenon as a network of protein architectures connected by shared domains. Figure 5 displays the biggest connected sub-network of architectures found, which harbors many known effector domains such as ankyrin repeats (Ank), leucine-rich repeat (LRR) and phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate binding domain (PI4P). The network clearly demonstrates that several domains are present in numerous effectors (indicated by the node size in Fig. 5), as well as in numerous different architectures (indicated in Fig. 5 by the number of connected nodes harboring the same LED). For example: (i) the ankyrin repeats, known to mediate protein-protein interactions, were found in all 41 species analyzed as part of 22 different architectures, and altogether in 301 effectors. (ii) The LRR domain, also involved in protein-protein interactions, was found in 37 species, as part of six architectures in 140 effectors. (ii) A novel domain of unknown function (LED06) was part of 12 architectures in 136 effectors from 30 species. Beside these three most abundant LEDs, the network represents a wealth of domains with known and unknown functions, from which insights regarding possible effector functions can be deduced, as described below.

Figure 5. Protein architecture network of effectors.

Each node represents a specific protein architecture (combination of effector domains). Node labels indicate domains taking part in the architecture. Edges represent domains shared between architectures. Known domains are colored; novel conserved effector domains are in grey. Node size is proportional to the number of ORFs with the architecture represented by the node.

The PI4P-binding domain was previously shown to localize effectors (including lpg2464-SidM/DrrA, lpg1101, and lpg2603) to the LCV46,48. This domain is of special interest since it can serve to predict which functions might be targeted to the LCV in different Legionella species. A PI4P-binding domain was found as part of eight architectures in 36 putative effectors. In all these architectures, the PI4P-binding domain was located at the C-terminal end, and in some cases an additional conserved domain with known function was found on the same effector (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 8). For example, in L. parisiensis PI4P was found on a putative effector (Lpar_1114) together with the U-box domain. U-box is typically found in ubiquitin-protein ligases where it determines the substrate specificity for ubiquitylation (E3 ubiquitin ligases)49. In L. pneumophila a U-box domain was previously proved to be functional in the effector LegU2/LubX (lpg2830)35, which does not contain PI4P. The presence of U-box together with PI4P in Lpar_1114 suggests that this effector is involved in protein ubiquitylation on the LCV. Interestingly, it was previously shown that ubiquitylation occurs on the L. pneumophila LCV as well, but no ORF containing both a PI4P and U-box domains was found in this species. Instead, in L. pneumophila this function is mediated (at least in part) by LegAU13/AnkB (lpg2144), which contains both a U-box domain and an ankyrin repeat. This effector anchors to the LCV membrane by host-mediated farnesylation that occurs at the C-terminal end of the protein50,51. Collectively, these results demonstrate that Legionella species use a variety of molecular mechanisms to direct effectors to the LCV, even if the function that these effectors perform on the LCV is similar.

Figure 6. Architectures containing either PI4P-binding domain or LED006.

Each protein architecture containing either PI4P-binding domain or the novel uncharacterized LED0006 is represented by a single putative effector.

An additional domain found together with the PI4P-binding domain, was glycosyltransferase, which glycosylates proteins. In L. pneumophila a functional glycosyltransferase domain was found in the N-terminus of the SetA effector (lpg1978), in which a C-terminal phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate binding domain (PI3P) is required for proper localization to the early LCV52 (PI3P and PI4P-binding domains share no homology). We found a glycosyltransferase domain together with the PI4P-binding domain in putative effectors from three species (Supplementary Fig. 8), suggesting that these putative effectors also localize to the LCV. The presence of various additional domains together with the PI4P-binding domain (Fig. 6), including protein tyrosine kinase (PTK), haloacid dehalogenase-like hydrolases (HAD), deoxy-rebonuclease, J-domain, and one unknown domain (LED022), implies that in different Legionella species several additional functions are targeted to the LCV using PI4P. In addition to the abovementioned protein architectures, seven LEOGs contained a PI4P localization domain in their C-terminus with no additional conserved domain in their N-terminus. These LEOGs might encode unique functions, not present in other effectors, possibly representing recent domain incorporation to effectors functioning on the LCV.

Analysis of the architectures containing the PI4P-binding domain provided putative insights into the function of LED006, an abundant novel domain. Both the PI4P domain and LED006 were found together with PTK, glycosyltransferase, and a domain with unknown function – LED022 (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 8). Similar to the PI4P-binding domain, LED006 was also located at the C-terminal end of all the putative effectors in which it was found. The L. pneumophila effector LepB (lpg2490), which contains the LED006 domain, is known to localize to the LCV34,53 and to function as a GTPase activating protein (GAP) for the Rab1 protein (a small GTPase known to regulate ER to Golgi trafficking54). It was previously shown that a region overlapping LED006 is required for LepB targeting to the LCV34,53. Additionally, effectors containing the LED006 domain often harbor a functional domain at their N-terminus. These observations suggest that LED006 is another domain involved in the targeting of effectors to the LCV. Presumably, putative effectors in which only LED006 was identified, contain an N-terminal domain that was not conserved enough to be identify by the stringent methods we applied.

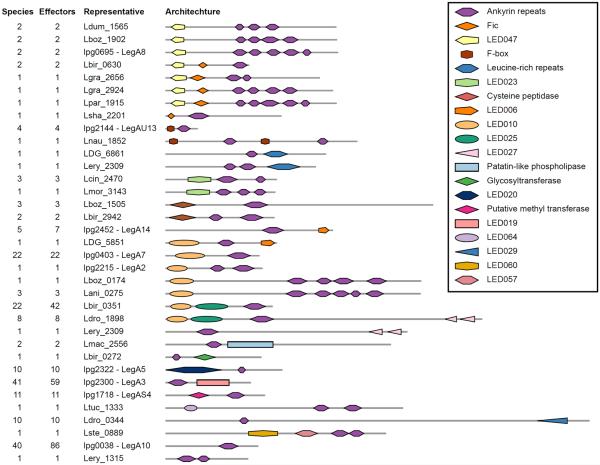

Ankyrin repeats appear with a multitude of other domains and in different species, each having its own domain combination repertoire (Fig. 7. and Supplementary Fig. 9). Overall ankyrin repeats were found in more than 300 putative effectors and is present in 22 different architectures (35 architectures when taking into account different numbers of repeats). While some of the ankyrin-containing architectures are present only in species-specific effectors, others are widespread and appear in all 41 species analyzed. Some domains, including F-box, Fic and LRR, were found adjacent to varying numbers of ankyrin repeats in different effectors, further demonstrating the degree of domain variability in Legionella effectors. Ankyrin repeats function as a protein-protein interaction domain, directing effectors to their target protein in the host. Thus, effectors with ankyrin repeats might target a host protein to the LCV, in which case they are expected to also have a localization domain. Alternatively, effector with ankyrin repeats might have an enzymatic domain that serves to manipulate a host protein.

Figure 7. Diversity of ankyrin-containing putative effectors.

Each domain configuration that includes an ankyrin domain is represented by a single example (architectures with different number of ankyrin repeats are represented separately). The number of putative effectors, as well as the number of Legionella species in which each configuration occurs, are indicated.

The various architectures in which the domains are found, and the different organizations of shared domains, demonstrate the vast functional variability of the Legionella genus effectors and the important effect that domain shuffling has on the evolution of the virulence system of these intracellular pathogens.

DISCUSSION

Pathogens belonging to the Legionella genus cause severe, often fatal, disease in human. This is achieved despite the fact that Legionella have not coevolved with humans: Legionella are not transmitted person-to-person, and thus they are either defeated by their human host or perish with it. The reason they are able to manipulate human pathways is due to a large and versatile repertoire of effector proteins acquired during their coevolution with a variety of protozoan hosts. De novo sequencing of 38 Legionella species, allowed us to predict and extensively analyze an enormous cohort of 5,885 putative effectors belonging to more than 600 orthologous groups. The effectors were predicted using stringent species-specific cutoffs in order to minimize false detection. Hence, the total number of effectors is expected to be higher. We estimate, based on a second round of predictions performed on the combined set of genomes (see Methods), that the total number of effectors in the genomes analyzed might be as high as 9,300. This amounts to 7.2% of all the ORFs, compared to L. pneumophila, where 10% of its genome encodes for validated effectors.

We found that vast majority (78.5%) of the 5,885 putative effectors identified in this study are shared by less than ten species, and only a handful of effectors are shared across the genus. These findings, combined with the atypically low GC content of species-specific effectors, suggest that these are recently acquired genes, probably part of an ongoing process of acquiring genes from hosts and co-infecting pathogens, and adapting them to function as effectors. Importantly, we identified dozens of conserved effector domains, which uncovered the basic building blocks that, when rearranged during the course of evolution, contribute to the myriad of functions exerted by Legionella effectors.

ONLINE METHODS

Sequencing, assembly, and annotation

Thirty-eight Legionella isolates of the following species were collected: L. adelaidensis, L. anisa, L. birminghamensis, L. bozemanii, L. brunensis, L. cherrii, L. cincinnatiensis, L. drozanskii, L. dumoffii, L. erythra, L. feeleii, L. geestiana, L. gormanii, L. gratiana, L. hackeliae, L. israelensis, L. jamestowniensis, L. jordanis, L. lansingensis, L. londiniensis, L. maceachernii, L. micdadei, L. moravica, L. nautarum, L. oakridgensis, L. parisiensis, L. quateirensis, L. quinlivanii, L. rubrilucens, L. sainthelensi, L. santicrucis, L. shakespearei, L. spiritensis, L. steelei, L. steigerwaltii, L. tucsonensis, L. waltersii, L. worsleiensis (Supplementary Table 1). DNA was extracted from each sample using DNeasy kit (Qiagen, CA) including proteinase K and RNase treatments, and following manufacturer's instructions. The DNA was sequenced using Illumina HiSeq platform producing a total of 773 Gbps of 100 bp pair-ends reads with a target insert size of 200 – 300 bps. Low quality reads from each of the samples was trimmed using Trimmomatic55, and trimmed reads were assembled using Velvet56. Combination of different Trimmomatic parameters and Velvet K-mer values were used to optimize assembly, as measured by N50, (Supplementary Table 2).

Open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted using Prodigal57 with default parameters. The ORFs from the different genomes were clusters into Legionella Ortholog groups (LOGs) using OrthoMCL58 (Supplementary Table 3). To assess genome completeness we examined the presence of 55 genes consisting of 31 single copy universal bacterial genes59, and the 24 genes encoding for the components of the Icm/Dot secretion system, which is universal in the Legionella genus. Out of the 38 sequenced genomes, 36 contained 100% of the genes examined, and two genomes (L. cherrii and L. santicrucis) missed a single gene each (Supplementary Table 4).

ORF annotation (Supplementary Table 10) was performed based on similarity to available fully sequenced Legionella genomes with preference to L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1. Specifically, annotation was transferred based on BLAST hits to L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1 (NCBI accession: NC_002942). If no significant hit was found vs. Philadelphia-1, than annotation was transferred from the best hit from the following genomes: L. longbeachae D-4968, L. longbeachae NSW150, L. pneumophila str. Corby, L. pneumophila 2300/99 Alcoy, L. pneumophila str. Paris, L. pneumophila str. Lens, L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila ATCC 43290, L. pneumophila subsp. Pneumophila, L. drancourtii LLAP12 (NCBI accessions: NC_006365-6, NC_006368-9, NC_009494, NC_013861, NC_014125, NC_014544, NC_016811, NC_018139, NC_018140-1, NZ_ACZG01000001-13, NZ_JH413793-850).

Machine learning approach for effector prediction

Icm/Dot effector prediction was performed using the machine-learning approach we have previously described23. Briefly, for each ORF in each genome, we calculated an array of features that expected to be informative for the classification of the ORF as an effector. The features used for the learning included ORF length, GC content, similarity to proteins in sequenced Legionella hosts (Human, Tetrahymena thermophila, Dictyostelium discoideum), similarity to C. burnetii RSA-493 ORFs, similarity to known effectors, existence of eukaryotic domains typically found in effectors, amino-acid composition, similarity of CpxR and PmrA binding sites within regulatory region, presence of CAAX (merystilation pattern), information regarding transmembrane domains, coiled-coils domains, similarity of amino-acid profile to that of known effectors, and the strength of the Icm/Dot secretion signal20. The full list of features used is specified in Supplementary Table 11. These features served as input to four different machine-learning classification algorithms: (i) naïve Bayes60; (ii) Bayesian networks61 (iii) support vector machine (SVM)62; and (iv) random forest63. The final prediction score of each ORF was calculated as a weighted mean of the prediction scores of the four classification algorithms, where the weights are based on the estimated performance of each algorithm. These performances were evaluated by the mean area under the precision-recall curve, over 10-fold cross-validation. The prediction score and the Icm/Dot secretion signal score for each ORF are detailed in Supplementary Table 10.

The machine-learning prediction procedure was performed separately for each genome to account for the unique effector characteristic in each species. The training-set for each species comprised of close homologs of validated effectors (based on BLAST bit score ≥ 60, marked by `H' in Supplementary Table 10). These effectors were used to train the machine-learning scheme that performed predictions for each genome separately. The machine learning score threshold to consider an ORF as a putative effector was selected such that the set of effectors in each genome includes at least a third of the effectors from the training-set, but no more than a third of the ORFs above it are newly predicted effector. This is a conservative threshold: it increased the set of effectors over the training set only by 22.4% (ORFs marked by `ML' in Supplementary Table 10). In addition, ORFs that were part of ortholog groups that included ≥ 80% effectors were also considered as effectors by orthology (marked by `O' in Supplementary Table 10). Only a very small fraction of the effectors (1.5%) were added due to orthology.

To test the significance of the different number of effectors encoded by the species across major clades, an ANOVA test allowing comparison of means across numerous groups was used. The values of percent ORFs that encode for effectors were compared across the clades marked by different colors in Figure 1. The percent of effectors in each genome was used, rather than the effector count, to account for differences in genome lengths.

Effector repertoire similarity was calculated as the mean of (1) the fraction of effector ortholog groups shared between species i and j, out of all the effector ortholog groups represented in species i and (2) the fraction of effector ortholog groups shared between species i and j, out of all the effector ortholog groups represented in species j.

Effector pseudogenes were identified by performing a strict BLAST search (e-value ≤ 1×10−10) of all putative effector genes against the sequenced genomes. Pseudogenes were identifies if they covered at least 80% of the homologous effector, and had between one to four stop codons that split the effectors into two or more parts of significant length: the second largest ORF was required to be more than 20% of the homologous proteins to avoid detection of slightly shorter proteins.

In order to estimate of the total number of effectors in the 41 Legionella species, we performed a second round of learning, based on the validated effectors and the putative effectors predicted by the strict species-specific thresholds in the first round of learning. This learning was performed on a combined dataset including all the genomes to allow effectors detected in one species in the first round to aid the identification of effectors in other species in this round of prediction (the scores are detailed in Supplementary Table 10). Since this learning is based on effectors that have not yet been validated, the predictions should be considered speculative, but can be useful to estimate the total number of effectors in the genomes analyzed. The number of novel high-scoring prediction (score > 0.99) was 2,643. Based on training set's false positives rate, we deduced that 744 additional effectors were scored below this threshold. Combining these values with the 5,885 putative effectors used as an input to this learning led us to estimate that the total number of effectors is approximately 9,272.

Phylogeny reconstruction and evolutionary analyses

An initial evolutionary tree was reconstructed based on concatenated alignments of proteins belonging to 93 ortholog groups that had one ortholog per Legionella species, and have been reported to be nearly universal in bacteria64. For each one of these 93 proteins a separate tree was also reconstructed and compared to the concatenated tree using the AU-test24 on the protein's multiple sequence alignment. AU-test (Approximately-Unbiased test) checks whether an observed multiple sequence alignment is significantly more supported by one of two maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Fifteen proteins with gene trees that were significantly different from the combined phylogeny (AU-test p-value < 0.01, after FDR correction for multiple testing25) were filtered out. The final phylogeny was achieved by reconstructing an evolutionary tree based on the concatenated alignment of the remaining 75 nearly universal single-copy proteins (marked in Supplementary Table 3).

The evolutionary gain and loss of effectors were computed as described in Cohen et al. 201065. Briefly, the phyletic pattern of effectors was coded as a gapless alignment of 0s and 1s representing, respectively, the absence or presence of specific effector families in each of the analyzed genomes. The gain and loss rates of effectors were inferred using a maximum likelihood framework allowing for gene-specific variable gain/loss ratio. The inference of branch-specific gain and loss events was done by a stochastic mapping approach that accounts for the tree topology, branch lengths, effector-specific evolutionary rates, and the posterior probability of presence at each node of the tree.

To determine whether the presents of the core effectors LOG_00341 (Lpg2832) and LOG_01049 (RavC) in a few bacterial species outside of the genus is the result of HGT events, or multiple loss events, we compared the likelihood of two probabilistic models: one model allowing both gain (HGT) and loss, and a simpler model allowing only loss events. We tested these two models across an extensive set of 1,165 microbial genomes, with phylogeny based on MicrobesOnline66 species tree, by running probabilistic GLOOME67 algorithm with a “gain and loss” model, and a “loss only” model. The statistical significance of the difference between the models was calculated by likelihood ratio test between the log-likelihood obtained by the two alternative models.

Coevolution of syntenic effectors was estimated based on the extent to which pairs of effectors are gained and lost together during their evolutionary histories among the Legionella genomes. We used the algorithm CoPAP68 that apply a probabilistic framework in which the gain and loss events are stochastically mapped onto the phylogeny. The co-evolutionary strength is measured while taking into account the correlation among gain and loss for pairs of effectors that underwent at least two such events, while accounting for the overall event rate

The evolutionary history of putative effectors that underwent HGT within the Legionella genus, was analyzed by reconstructing the gene trees for 96 effectors present in 4–40 species, that had no paralogues, and were inferred to be gained at least twice during the genus evolution. These trees were compared to the species tree using AU-test24, and the obtained p-values were corrected for multiple testing using FDR25.

All tree reconstruction were done using RAxML69 under the LG+GAMMA+F evolutionary model with 100 bootstrap re-samplings. AU-test p-value was calculated using CONSEL70. Coxiella burnetii was used as an out-group to root the tree.

Plasmid construction

To construct deletion substitutions in the seven L. pneumophila core-effectors, a 1-kb DNA fragment located on each side of the planned deletion was amplified by PCR using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 12. The primers were designed to contain a SalI site at the place of the deletion. The two fragments that were amplified for each gene were cloned into pUC-18 digested with suitable enzymes to generate the plasmids listed in Supplementary Table 12. The resulting plasmids were digested with suitable enzymes, and the inserts were used for a four-way ligation containing the kanamycin (Km) resistance cassette (Pharmacia) digested with SalI and the pUC-18 vector digested with suitable enzymes. The desired plasmids were identified by plating the bacteria on plates containing ampicillin and Km, and after plasmid preparation the desired clones were identified by restriction digests. The plasmids generated (Supplementary Table 12) were digested with PvuII (this enzyme cuts on both sides of the pUC-18 polylinker), and the resulting fragments were cloned into the pLAW344 allelic exchange vector digested with EcoRV to generate the plasmids that were used for allelic exchange (listed in Supplementary Table 12), as described previously71.

To construct isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible effectors, the L. pneumophila legA3 and mavN genes were amplified by PCR using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 12. The PCR products were then digested with BamHI and SalI for legA3 and with EcoRI and BamHI for mavN and cloned into pMMB207C downstream from the Ptac promoter to generate the plasmids listed in Supplementary Table 12. These plasmids contain the effectors under Ptac control, and they were used for intracellular growth complementation. Intracellular growth assays of L. pneumophila strains in Acanthamoeba castellanii were performed as previously described72.

Identification of Legionella effector domains

Each Legionella effector ortholog group (LEOG) was represented by a hidden Markov model (HMM), which was constructed as follows. The proteins belonging to a given ortholog group were aligned by MAFFT73 version v7.164b using the `einsi' strategy. HMMs were constructed from the multiple sequence alignments using hmmbuild from the HMMER suite74 version 3.1b1.

Characterized domains were identified by comparing LEOG HMMs to domain databases using hhsearch version 2.0.15 from the HH-suite75. Specifically, a hhsearch with e-value threshold of 10−5 was used to find similarities between the LEOG HMMs and HMMs derived from following databases: (1) NCBI's Conserved Domain Database (CDD)76, (2) Pfam77, and (3) SMART78, which were downloaded from the HH-suite ftp site (ftp://toolkit.genzentrum.lmu.de/pub/HH-suite/). Resulting hits were manually curated to filter out domains of unknown functions and non-informative domains. Additional characterized domains were identified during the process of novel domain detection.

Novel domains were identified as follows. All against all BLAST79 search of all 5,885 putative Legionella effectors was performed with e-value cutoff of 0.001. From the BLAST hits that received bit score > 40, we extracted maximal joined segments longer than 50 amino acids that were nearly non-overlapping (overlap < 10 amino acids). The extracted segments were searched using BLAST against the putative effector dataset using a threshold of 40 bit score. Hits of segments that had four or more hits were aligned and used to construct HMMs (as described above). These HMMs, representing conserved domains, were compared to each other using hhsearch. HMMs with homology probability score of ≥ 95% and e-value < 0.01 across at least 50% of their length were designated as describing the same domain. The detected domain HMMs were scanned for coiled-coil domains using COILS80, and domains that were ≥ 80% covered by coiled-coil domains were labeled as coiled-coiled domains. The domain HMMs were further scanned against the HMM databases of CDD76, Pfam77, and SMART78, and those with homology probability score ≥ 95% and e-value < 0.01 across at least 50% of their length were annotated according to the characterized domain (after excluding non-informative hits). The domain HMMs were used to scan the putative effectors dataset. A domain was considered as a novel Legionella effector domain if it did not overlap any characterized domain and appeared in at least 80% of the members of two different ortholog groups, each composed of at least two putative effectors.

In the effector-domain network each node represents an architecture, i.e., a combination of domains that was present in the same effector. An edge between two architecture nodes represents a domain that is shared by the two architectures. The size of each node is proportional to the number of putative effectors that had the architecture represented by the node. The network was visualized using the igraph package81 of R82. The domain architecture trees topology is of the species trees built based on 78 single copy genes as specified above. The trees were visualized using iTOL83.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Icm/Dot secretion system region I in 41 Legionella species. Homolog of the effector-coding gene legA15 (orange) was found within Icm/Dot region I in 13 Legionella species. In four genomes other putative effectors (bright yellow) were also found in this region. Genes colored in grey represent non-effector genes found between the two parts of the region. In nine genomes there are no genes other than Icm/Dot coding genes in the region. Icm/Dot genes symbols: V: icmV, W: icmW, X: icmX, A: dotA, B: dotB, C: dotC, D: dotD.

Supplementary Figure 2. Workflow overview. A graphical summary presenting the main analyses performed in this study, and the output at each stage.

Supplementary Figure 3. Testing for bias in effector detection. (a) Comparison of the amount of putative effectors and ORFs with Icm/Dot C-terminal translocation signal per species. In order to display both values on the same scale, the x-axis represents the percentage out of the total set of ORFs of interest that was detected in each species. The species tree is presented on the left. (b) Correlation between the number of putative effectors and number of ORFs with C-terminal Icm/Dot translocation signal. A strong (R2=0.762) and significant correlation (p-value 1.004×10−13, Pearson correlation test) was found between the two. Both the number of effector and the number of ORF with translocation signal per species did not significantly deviated from the normal distribution, Shapiro-Wilk normality test p-values 0.43 and 0.68, respectively). (c) Correlation between the evolutionary distance from L. pneumophila and the ratio of putative-effectors to ORFs with Icm/Dot C-terminal translocation signal. No significant correlation was detected (p-value 0.14 Spearman correlation test), suggesting there is probably no significant preferential effector detection in species closer to L. pneumophila. Spearman correlation was used since both distributions deviated from normality (p-value 0.004 and 0.01 respectively, Shapiro-Wilk test).

Supplementary Figure 4. The evolution of the seven core effectors. Maximum likelihood phylogenies are presented for the core effectors along with the species tree. Numbers next to inner nodes denote the bootstrap values.

Supplementary Figure 5. Mutants lacking each of the two core effectors exhibit an intracellular growth phenotype. Intracellular growth in A. castellanii of deletion mutates of legA3 (a) and mavN (b) compared to wild type and plasmid complementation indicate that these two core effectors affect intracellular growth. The five other core effectors did not display an intracellular growth phenotype in A. castellanii. The growth curves represent the averages and standard deviations of three repetitions of the experiments.

Supplementary Figure 6. Legionella species and effector evolution. Based on phyletic patterns of effector presence/absence, the number of effector gain events and the number of effector loss events were computed using a maximum likelihood algorithm65. The pie size is proportional to the rate of events (number of events normalized to branch length). Each pie represents the ratio between gain (green) and loss (red) of effectors. The results suggest that the “L. pneumophila clade” (species marked in dark red) is much more prone to gain and loss of effectors than the “L. micdadei clade” (marked in dark green). The numbers on the right refer to the cluster of effector repertoires in Figure 4, indicating that these clusters are in agreement with the Legionella phylogeny.

Supplementary Figure 7. Comparison of the Legionella genus tree to gene trees of effectors that underwent HGT. The gene tree of effectors that underwent at least 2 gain events, had no paralogues, and was present in at least four species was reconstructed and compared to an appropriate pruned version of the species tree using AU-test. Q-values were calculated by adjusting resulting p-values using FDR25 to account for multiple testing. The plot displays the distribution of −log(q-value) over 96 effectors compared to the species tree. The blue dashed line note the 0.01 cutoff. Most of the effectors tree agrees with the pruned version of the species tree, suggesting there is a preferential horizontal gene transfer of effectors among evolutionary close species.

Supplementary Figure 8. Putative effectors coding for PI4P-binding domain. All the putative effectors harboring a PI4P-binding domain are presented on the Legionella species tree.

Supplementary Figure 9. Putative effectors coding for the ankyrin domain. All the putative effectors with ankyrin repeats are presented on the Legionella species tree.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by 5RO1 AI23549 (H.A.S.) and the costs of DNA sequencing were supported by startup funds from the Division of Biological Sciences of the University of Chicago (HAS). This work was also supported in part by grant 2013240 from the United States Israel Binational Science Foundation (G.S. and H.A.S.). D.B. was a fellow of the Converging Technologies Program of the Israeli Council for Higher Education. D.B. and T.P. were supported by the Edmond J. Safra Center for Bioinformatics at Tel Aviv University. F.A. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Fulbright Commission and Ministry of Education of Spain. We wish to thank Eli Levy Karin for the kind help she provided with some of the phylogenetic analyses.

Footnotes

Accession codes The genomic sequences of the 38 assembled genomes will be available at NCBI BioProject under accession PRJNA285910.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fields BS. The molecular ecology of legionellae. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:286–290. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fields BS, Benson RF, Besser RE. Legionella and Legionnaires' Disease: 25 Years of Investigation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002;15:506–526. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.3.506-526.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diederen BMW. Legionella spp. and Legionnaires' disease. J. Infect. 2008;56:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horwitz MA. The Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) inhibits phagosome-lysosome fusion in human monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1983;158:2108–2126. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.6.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horwitz MA. Formation of a novel phagosome by the Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) in human monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1983;158:1319–1331. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.4.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kagan JC, Roy CR. Legionella phagosomes intercept vesicular traffic from endoplasmic reticulum exit sites. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:945–954. doi: 10.1038/ncb883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segal G, Purcell M, Shuman HA. Host cell killing and bacterial conjugation require overlapping sets of genes within a 22-kb region of the Legionella pneumophila genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:1669–1674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogel JP, Andrews HL, Wong SK, Isberg RR. Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Science. 1998;279:873–876. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isberg RR, O'Connor TJ, Heidtman M. The Legionella pneumophila replication vacuole: making a cosy niche inside host cells. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldman M, Zusman T, Hagag S, Segal G. Coevolution between nonhomologous but functionally similar proteins and their conserved partners in the Legionella pathogenesis system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:12206–12211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501850102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldman M, Segal G. A specific genomic location within the icm/dot pathogenesis region of different Legionella species encodes functionally similar but nonhomologous virulence proteins. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:4503–4511. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4503-4511.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beare PA, et al. Dot/Icm type IVB secretion system requirements for Coxiella burnetii growth in human macrophages. mBio. 2011;2:e00175–11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00175-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carey KL, Newton HJ, Lührmann A, Roy CR. The Coxiella burnetii Dot/Icm system delivers a unique repertoire of type IV effectors into host cells and is required for intracellular replication. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002056. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leclerque A, Kleespies RG. Type IV secretion system components as phylogenetic markers of entomopathogenic bacteria of the genus Rickettsiella. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008;279:167–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Connor TJ, Adepoju Y, Boyd D, Isberg RR. Minimization of the Legionella pneumophila genome reveals chromosomal regions involved in host range expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011;108:14733–14740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111678108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Connor TJ, Boyd D, Dorer MS, Isberg RR. Aggravating genetic interactions allow a solution to redundancy in a bacterial pathogen. Science. 2012;338:1440–1444. doi: 10.1126/science.1229556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muder RR, Victor LY. Infection due to Legionella species other than L. pneumophila. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002;35:990–998. doi: 10.1086/342884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ko KS, et al. Application of RNA Polymerase β-Subunit Gene (rpoB) Sequences for the Molecular Differentiation of Legionella Species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002;40:2653–2658. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2653-2658.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Segal G, Feldman M, Zusman T. The Icm/Dot type-IV secretion systems of Legionella pneumophila and Coxiella burnetii. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005;29:65–81. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lifshitz Z, et al. Computational modeling and experimental validation of the Legionella and Coxiella virulence-related type-IVB secretion signal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013;110:E707–E715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215278110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomez-Valero L, Rusniok C, Cazalet C, Buchrieser C. Comparative and functional genomics of Legionella identified eukaryotic like proteins as key players in host–pathogen interactions. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. - Closed Sect. 2011;2:208. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burstein D, et al. Genome-scale identification of Legionella pneumophila effectors using a machine learning approach. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000508. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lifshitz Z, et al. Identification of novel Coxiella burnetii Icm/Dot effectors and genetic analysis of their involvement in modulating a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Infect. Immun. 2014;82:3740–3752. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01729-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimodaira H. An Approximately Unbiased Test of Phylogenetic Tree Selection. Syst. Biol. 2002;51:492–508. doi: 10.1080/10635150290069913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bork P. Hundreds of ankyrin-like repeats in functionally diverse proteins: Mobile modules that cross phyla horizontally? Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 1993;17:363–374. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosavi LK, Cammett TJ, Desrosiers DC, Peng Z. The ankyrin repeat as molecular architecture for protein recognition. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. 2004;13:1435–1448. doi: 10.1110/ps.03554604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Portier E, et al. IroT/mavN, a new iron-regulated gene involved in Legionella pneumophila virulence against amoebae and macrophages. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;17:1338–1350. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isaac DT, Laguna RK, Valtz N, Isberg RR. MavN is a Legionella pneumophila vacuole-associated protein required for efficient iron acquisition during intracellular growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015;112:E5208–E5217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511389112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hennecke H. Nitrogen fixation genes involved in the Bradyrhizobium japonicum-soybean symbiosis. FEBS Lett. 1990;268:422–426. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaneko T, et al. Complete genomic sequence of nitrogen-fixing symbiotic bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110. DNA Res. 2002;9:189–197. doi: 10.1093/dnares/9.6.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan Y, Luo Z-Q. Legionella pneumophila SidD is a deAMPylase that modifies Rab1. Nature. 2011;475:506–509. doi: 10.1038/nature10307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neunuebel MR, et al. De-AMPylation of the Small GTPase Rab1 by the Pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Science. 2011;333:453–456. doi: 10.1126/science.1207193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ingmundson A, Delprato A, Lambright DG, Roy CR. Legionella pneumophila proteins that regulate Rab1 membrane cycling. Nature. 2007;450:365–369. doi: 10.1038/nature06336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kubori T, Shinzawa N, Kanuka H, Nagai H. Legionella metaeffector exploits host proteasome to temporally regulate cognate effector. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001216. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeong KC, Sexton JA, Vogel JP. Spatiotemporal regulation of a Legionella pneumophila T4SS substrate by the metaeffector SidJ. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004695. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Havey JC, Roy CR. Toxicity and SidJ-mediated suppression of toxicity require distinct regions in the SidE family of Legionella pneumophila effectors. Infect. Immun. 2015;83:3506–3514. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00497-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen X, et al. Targeting eEF1A by a Legionella pneumophila effector leads to inhibition of protein synthesis and induction of host stress response. Cell. Microbiol. 2009;11:911–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fontana MF, et al. Secreted bacterial effectors that inhibit host protein synthesis are critical for induction of the innate immune response to virulent Legionella pneumophila. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001289. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li X-Q, Du D. Variation, evolution, and correlation analysis of C+G content and genome or chromosome size in different kingdoms and phyla. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e88339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collingro A, et al. `Candidatus Protochlamydia amoebophila', an endosymbiont of Acanthamoeba spp. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005;55:1863–1866. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63572-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Altman E, Segal G. The response regulator CpxR directly regulates txpression of several Legionella pneumophila icm/dot components as well as new translocated substrates. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:1985–1996. doi: 10.1128/JB.01493-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zusman T, et al. The response regulator PmrA is a major regulator of the icm/dot type IV secretion system in Legionella pneumophila and Coxiella burnetii. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;63:1508–1523. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cazalet C, et al. Evidence in the Legionella pneumophila genome for exploitation of host cell functions and high genome plasticity. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:1165–1173. doi: 10.1038/ng1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Felipe K. S. de, et al. Evidence for acquisition of Legionella type IV secretion substrates via interdomain horizontal gene transfer. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:7716–7726. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.22.7716-7726.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brombacher E, et al. Rab1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor SidM is a major phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate-binding effector protein of Legionella pneumophila. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:4846–4856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807505200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weber SS, Ragaz C, Reus K, Nyfeler Y, Hilbi H. Legionella pneumophila exploits PI(4)P to anchor secreted effector proteins to the replicative vacuole. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e46. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hubber A, et al. The machinery at endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane contact sites contributes to spatial regulation of multiple Legionella rffector proteins. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004222. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ardley H, Robinson P. E3 ubiquitin ligases. Essays Biochem. 2005;41:15–30. doi: 10.1042/EB0410015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Price CTD, Quadan T. Al-, Santic M, Jones SC, Kwaik YA. Exploitation of conserved eukaryotic host cell farnesylation machinery by an F-box effector of Legionella pneumophila. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:1713–1726. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Price CTD, Quadan T. Al-, Santic M, Rosenshine I, Kwaik YA. Host proteasomal degradation generates amino acids essential for intracellular bacterial growth. Science. 2011;334:1553–1557. doi: 10.1126/science.1212868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jank T, et al. Domain organization of Legionella effector SetA. Cell. Microbiol. 2012;14:852–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mishra AK, Campo CMD, Collins RE, Roy CR, Lambright DG. The Legionella pneumophila GTPase activating protein LepB accelerates Rab1 deactivation by a non-canonical hydrolytic mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:24000–24011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.470625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mizuno-Yamasaki E, Rivera-Molina F, Novick P. GTPase networks in membrane traffic. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012;81:637–659. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052810-093700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joshi NA, Fass JN. Sickle: A sliding-window, adaptive, quality-based trimming tool for FastQ files (Version 1.33) [Software] 2011 at < https://github.com/najoshi/sickle>.

- 56.Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: Algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18:821–829. doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hyatt D, et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: Identification of ortholog groups for rukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu M, Eisen JA. A simple, fast, and accurate method of phylogenomic inference. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R151. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-10-r151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Langley P, Iba W, Thompson K. Proceedings of the Tenth National Conference on Artificial Intelligence. AAAI Press; 1992. An analysis of Bayesian classifiers; pp. 223–228. at < http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1867135.1867170>. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heckerman D, Geiger D, Chickering DM. Learning Bayesian networks: The combination of knowledge and statistical data. Mach. Learn. 1995;20:197–243. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burges CJC. A tutorial on support vector machines for pattern recognition. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 1998;2:121–167. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Breiman L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Puigbò P, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Search for a `Tree of Life' in the thicket of the phylogenetic forest. J. Biol. 2009;8:59. doi: 10.1186/jbiol159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cohen O, Pupko T. Inference and characterization of horizontally transferred gene families using stochastic mapping. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010;27:703–713. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dehal PS, et al. MicrobesOnline: an integrated portal for comparative and functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D396–D400. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cohen O, Ashkenazy H, Belinky F, Huchon D, Pupko T. GLOOME: gain loss mapping engine. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2914–2915. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cohen O, Ashkenazy H, Levy Karin E, Burstein D, Pupko T. CoPAP: Coevolution of Presence-Absence Patterns. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W232–W237. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shimodaira H, Hasegawa M. CONSEL: for assessing the confidence of phylogenetic tree selection. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1246–1247. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Segal G, Shuman HA. Characterization of a new region required for macrophage killing by Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 1997;65:5057–5066. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5057-5066.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Segal G, Shuman HA. Legionella pneumophila utilizes the same genes to multiply within Acanthamoeba castellanii and human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:2117–2124. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2117-2124.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eddy SR. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Remmert M, Biegert A, Hauser A, Söding J. HHblits: lightning-fast iterative protein sequence searching by HMM-HMM alignment. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:173–175. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marchler-Bauer A, et al. CDD: a database of conserved domain alignments with links to domain three-dimensional structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:281–283. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]