Abstract

The health and well-being of single-parent families living in violent neighbourhoods in US cities who participate in housing programmes is not well described. This two-phase, mixed-methods study explores the health status of families who were participants in a housing-plus programme in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania between 2011 and 2013 and the relationship between the characteristics of the neighbourhoods in which they lived and their perceptions of well-being and safety. In phase 1, data collected with standardised health status instruments were analysed using descriptive statistics and independent sample t-tests to describe the health of single parents and one randomly selected child from each parent’s household in comparison to population norms. In a subset of survey respondents, focus groups were conducted to generate an in-depth understanding of the daily lives and stressors of these families. Focus group data were analysed using content analysis to identify key descriptive themes. In phase 2, daily activity path mapping, surveys and interviews of parent–child dyads were collected to assess how these families perceive their health, neighbourhood and the influence of neighbourhood characteristics on the families’ day-to-day experience. Narratives and activity maps were combined with crime data from the Philadelphia Police Department to analyse the relationship between crime and perceptions of fear and safety. Phase 1 data demonstrated that parent participants met or exceeded the national average for self-reported physical health but fell below the national average across all mental health domains. Over 40% reported moderate to severe symptoms of depression. Parents described high levels of stress resulting from competing priorities, financial instability, and concern for their children’s well-being and safety. Analysis of phase 2 data demonstrated that neighbourhood characteristics exert influence over parents’ perceptions of their environment and how they permit their children to move within it. This research suggests the need for robust research, programmatic and policy interventions to support housing-unstable families who live in neighbourhoods with high levels of violence.

Keywords: community-based research, housing and community care, neighbourhoods, parent welfare

Introduction

A family’s health is shaped by their home, its condition, the neighbourhood in which it is situated, and the economic resources required to maintain a safe and stable environment (Katz et al. 2001, Reid et al. 2008, Burgard et al. 2012, Ludwig et al. 2012). Inequities in housing and neighbourhood factors can attenuate the disproportionate burden of illness and injury in racial and ethnic minority populations (Braveman et al. 2011). Despite long-term improvements in life expectancy and health in the US overall, for example, there remains significant racial and ethnic disparities across a multitude of health conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, obesity, injury and mental health problems (Frieden, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2011). Racial and ethnic minority populations in the urban US are also more likely to live in violent neighbourhoods and have poorer access to quality education and stable housing (LaVeist 2011).

Housing and neighbourhood factors not only compound racial and ethnic disparities but they can also perpetuate disadvantages across generations; more often than not children are subject to many of the health risks faced by their parents and grandparents (Rodgers 1995, Wickrama et al. 1999). Over 50% of black families, for example, live in high-poverty neighbourhoods for consecutive generations, compared to just 7% of white families in high-poverty neighbourhoods (Sharkey 2008). This is important if we consider that low household income is associated with multiple health indicators like higher prevalence of illness (Remes et al. 2011) and poorer development in children (Noble et al. 2015).

The evidence that connects housing, neighbourhood factors and disparities in health is substantial but its direct application to population and community interventions is challenged by differences in how geographic, individual and life-course dimensions are evaluated across studies (Diez Roux 2001, Voigt-lander et al. 2014). There is also very little evidence to support a theoretical understanding of the pathways through which housing, neighbourhoods and health are inter-related in housing-unstable families who move frequently, often without self-selecting to their housing units. We do, however, know that domestic violence and poor physical and mental health predict homelessness and housing instability (Manning et al. 2010). Conversely, in a study of Michigan families affected by the recent US economic recession, being homeless within the past year was associated with poorer self-rated health, depression and alcohol abuse (Burgard et al. 2012). Children in housing-unstable families are similarly vulnerable to the negative health consequences of instability and are more likely to be food insecure, have lower than average weight and have poorer scores on standard development indices (Cutts et al. 2011). As adolescents, housing-unstable youth are at increased risk for pregnancy in their teen years, early drug use and depression (Lubell et al. 2007).

For housing-unstable families, economic and housing distress can force difficult choices between subsistence and health (Reid et al. 2008). Supportive housing programmes in communities with high levels of poverty and housing instability connect families with low-incomes and/or chronic health problems to affordable and permanent housing (Henwood et al. 2013). Affordable housing addresses health disparities by freeing up family income for resources like nutritious food and preventive healthcare and creates residential stability which can lessen stress and reduce exposure to stress-related illness and disability (Lubell et al. 2007, Cohen 2011). Theoretically, programmes seeking to improve families’ economic and residential self-sufficiency by helping parents gain education, employment and life skills are expected to improve family health. However, in the complexity of these families’ lives, improved employment and housing can unintentionally create new health risks. Maternal work requirements for US welfare recipients, for example, has been found to be a barrier to preventive healthcare utilisation in their children, when work requirements restrict time available for elective healthcare (Holl et al. 2012).

In addition to the unexplored health collateral associated with subsidised housing programmes, little is known about the relationship between individual health outcomes and the location of subsidised housing units in the context of a neighbourhood or city (Voigtlander et al. 2014). We know from landmark trials on neighbourhood effects and mental well-being, like the Moving to Opportunity study, that moving individuals from neighbourhoods with high crime and disorder to neighbourhoods with low crime and abundant resources can provide some long-term improvement across self-rated physical and mental health dimension to some family members (Katz et al. 2001, Ludwig et al. 2012). Whether or not this is effective, this type of intervention is extremely costly. Many urban housing interventions balance limited resources with community need and find that neighbourhoods with higher than average crime and lower than average community resources yield the greatest quantity of housing units at the lowest cost.

This two-phase, mixed-methods study describes the stressors that accompany the effort required for achieving self-sufficiency in a subsidised housing intervention and its associated health risks in a population of single parent, predominately female-headed, housing-unstable families. In a related analysis, our study team found that block-level micro-environmental data on income, education and crime rates were significantly associated with the rate at which parents in this housing intervention earned credits for advancing their educational attainment (Tach et al. 2016). We extend this line of research in the second phase of this study to explore whether families perceive the micro-environmental features and safety from crime and violence of where subsidised housing is located as a challenge to the benefit of stability.

Methods

Study design

This academic-community partnered, mixed-methods study was conducted in two phases. In phase 1 (2011–2012), we assessed the health status of all single parents who were current participants in a housing-plus programme in Philadelphia called ACHIEVEability (ACHa) and one randomly selected child from each parent’s household. We concurrently conducted focus group interviews with subset of participants and participants’ children to better understand their daily lives, stressors and neighbourhood context. In phase 2 (2013), we used a novel activity path mapping and interview technique to collect data on the daily activity patterns and perceptions of safety of a randomly selected subset of parent–child dyads from the ACHa programme. This phase of research was based on the ‘opportunity structure’ theory of small-area effects on health, in which small area was defined at the level of the environment immediately surrounding a daily activity path. This theoretical framework explores disparities in health based on differences in individual’s exposure to small-area resources and stressors (Macintyre et al. 2002). The University of Pennsylvania human subjects review board approved this study.

Setting

Participants for all phases of this study were recruited from ACHa’s housing programme in Philadelphia. ACHa owns 152 housing units clustered in a 2.1 square mile area of West Philadelphia and is structured on a housing-plus model (Cohen et al. 2004) that promotes the educational mobility of parents in order to optimise the family’s long-term economic well-being. To this end, ACHa provides homeless single-parent families housing at a subsided cost while requiring parental education, labour force participation and regular engagement with self-sufficiency coaches. This strategy is supported by research that suggests that increasing educational attainment has long-term economic benefits for families and that providing housing support can aid in the attainment of post-secondary education and employment (Lubell 2004). At the time of this study, ACHa was serving approximately 120 families that included 350 children. Over 90% of AchA participants self- identified as female, of Black or African American race, and single parents.

In the neighbourhoods in which ACHa provides services, one-third of residents live in poverty, and poverty rates are even higher among children and female-headed households (The Partnership Community Development Corporation 2010). These neighbourhoods experience pervasive community violence with youth homicide rates, robbery rates, juvenile arrests of drug-related offences and aggravated assaults well above the US national average (Cartographic Modeling Lab 2014).

Phase 1: Instruments and procedures

Parent health survey instruments

Every adult in ACHa who consented to participate completed a self-report health survey to measure: use of preventive care, health status, disability days, self-rated health status and well-being, stress and depression. We assessed disability using items validated for estimating functional disability including annual number of days of missed work and number of days of health-related bed rest in from the National Health Interview Survey. We measured individual stress and its impact on well-being with the Perceived Stress Scale. This scale, with established validity and reliability, is scored from 0 to 40 with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived stress (Cohen et al. 1983). We used the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D), a valid and reliable scale of depressive symptoms (Radloff 1977) to measure depression. CES-D scores range from 0 to 60 with higher scores indicating the presence of more depressive symptomatology. We measured health status using the Short Form 36 version 2 (SF-36 v.2), a self-report health status instrument that measures physical, emotional and mental well-being (Maruish & Kosonski 2008, Maruish & Turner-Bowker 2009). Scores are normalised to a scale of 0 to 100.

Child health survey instruments

Parents completed a survey on a child from their household and reported: demographic data, health-care access and usage, measures of psychosocial strengths and difficulties and physical and mental health status. For children aged 0–3, we only collected demographic and healthcare access and usage data. We used age appropriate versions of the Child Health Questionnaire short form (CHQ-PF28) to assess the health status of children between the ages of 4–17 years for comparison to national norms (Health ActCHQ 2008). We also collected data for children in this age group on parent-reported child behaviour using the parent version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire which measures five domains of childhood psychological attributes (emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems, prosocial behaviour) (Goodman 1997). Validity and reliability are established (Goodman et al. 1998); the total difficulties score ranges from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating more difficulties.

Health survey procedure

We recruited a census of ACHa participants through advertising in common areas of ACHa offices, personal invitations extended by ACHa personnel and word of mouth. Completion of the anonymous survey provided a de facto consent to participate. Parents completed the surveys for themselves and for one randomly assigned child (between the ages of 0 and 17 years) living in their household. The parent’s and child’s health survey were connected via a coding system that maintained anonymity. We offered several sessions in common meeting spaces at ACHa to administer surveys. To encourage wide participation, childcare was provided on site and refreshments were provided. In addition to these general sessions, clients were also able to complete surveys at individually scheduled times. Parents received a US$ 10 gift card at the completion of the surveys.

Focus groups

We recruited participants through advertising in ACHa common meeting areas, offices and in common areas of an ACHa-owned multi-family housing complex. Parents pre-registered themselves and/or their children to participate. Prior to initiation of interviews, a member of the research team explained the study, addressed study-related questions and obtained written informed consent. For the child focus groups, we obtained written constant from parents. We provided participating children with a simplified explanation of the study and obtained written assent.

Parents and children were interviewed in separate focus groups. We conducted four focus groups, two for parents and two for children (8–12 years and 13–17 years) that lasted for 1.5 hours each. Each focus group was facilitated by two members of the research team. Interviews were structured using a guide developed to elicit experiences in a housing-plus programme, the history of their housing instability, current life stressors and health challenges, strategies for coping with stressors, and perceptions of their daily activities and current neighbourhood. At the completion, adult participants received a gift card worth US $25 and children received a gift card worth US $10.

Phase 2: Daily activity mapping and narratives

We divided the 82 ACHa housing units with children eligible (8–17 years of age) to participate in this phase of research by crime rate into a high-crime stratum and a low-crime stratum. To achieve this stratification, we used the most recent crime data (2008) to map the count of violent crimes against persons and the rate of crimes per 10,000 population and smoothed these rates across block groups on which housing units were located. All housing units were within a 2.1 square mile area with significant variation of crime rates by block groups. Families were randomly selected based on their residential block (either high or low crime rate stratum), if they resided in permanent ACHa housing for at least 6 months, and if there was at least one child in the household aged 10 years and older. Parental consent and child assent were obtained in person prior to the interviews which took place in participants’ homes or in a private space at a mutually agreeable location. Parents and children were interviewed concurrently, but separately. Interviews lasted 30–60 minutes and at completion, parent and child each received a gift card (US $40 and US $25 respectively).

Parent and child participants completed a survey which included demographic and social variables and the Neighbourhood Environment Scale (NES). The NES has established validity and reliability across geographic and socio-demographic application to assess perceptions of the safety and social order of a neighbourhood (Crum et al. 1996). Higher scores indicate perceptions of a greater degree of neighbourhood disorder.

For activity mapping, parent participants identified a recent weekday (within the previous 3 days) and their child was instructed to use this same day to recall a 24-hour period of activity. Participants sat beside an interviewer and plotted their daily activity path on a laptop computer that showed a customised street-level map of their neighbourhood using ArcEngine software (ESRI Inc.: Redlands, CA, USA). As participants described their activity paths on the map, they answered questions about how, when, where and with whom they spent time as they travelled from activity to activity (Basta et al. 2010). Participants were asked, at each point of activity, about their perceptions of safety. Sense of safety was elicited using the question ‘How safe do you feel from fear of violence or crime on a scale of 0 to 10 in which 0 is very safe and 10 is very unsafe?’ Scores were reverse-scored for analysis such that 10 indicates feeling very safe and 0 indicates feeling very unsafe. Parent and child were separated during data collection and all interviews were audiotaped and transcribed.

Analysis

Phase 1

Missing data did not exceed 5% for any demographic or health variable across our sample of parent and child participants. Using SPSS version 21, we described the sample demographics and key health variables by measures of central tendency and variation. We scored physical and mental health status instruments and compared results from the sample of ACHa participants to population norms. T-tests were used to compare mean differences in self-reported health, perceived stress and child health status based on participants’ depression symptom burden. To test the precision of our results, missing data were evaluated using Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) test. Little’s MCAR test was not significant across any variable used to assess the relationship between depression symptom burden and health and well-being outcomes, which indicates that data were MCAR and our use of listwise deletion of missing data would not yield biased estimates.

Focus group data were transcribed. Transcriptions were verified for accuracy against the audiotape recordings and any content that included any personally identifiable details was removed or anonymised prior to analysis. We used content analysis to identify key codes, categories and themes from focus group data. Two of the researchers independently coded each transcript and then established a final categorical and thematic framework based on consensus. These categories and themes were reviewed and validated by the community partner.

Phase 2

Audiotapes of the parent–child dyad interviews were transcribed and transcriptions were verified for accuracy. We examined the content of interview narratives within the context of each participant’s daily activity path map and data. Activity maps were combined with environmental data from the Cartographic Modelling Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania, which provided an objective measure of crime in the block groups to contextualize participants’ subjective measures of fear and safety.

Findings

Phase 1: Sample description and health surveys

Parents

One hundred and one surveys were completed between July 2011 and March 2012. Ninety-nine per cent of survey respondents were women, with an average age of 32 years (SD: 8) and had been participants in ACHa for an average of 2.8 years (SD: 2.3). The majority had visited a healthcare provider in the past year and a dentist in the past 2 years. Only 1% reported they did not regularly seek preventive health services. To describe the average number of days missed from work due to health and days spent in bed due to health, we removed two outliers (more than 100 days missed work or in bed) prior to analysis. Participants missed work an average of 3.65 days (SD: 8) and spent 3.17 (SD: 5.7) days in bed in the previous month due to health reasons.

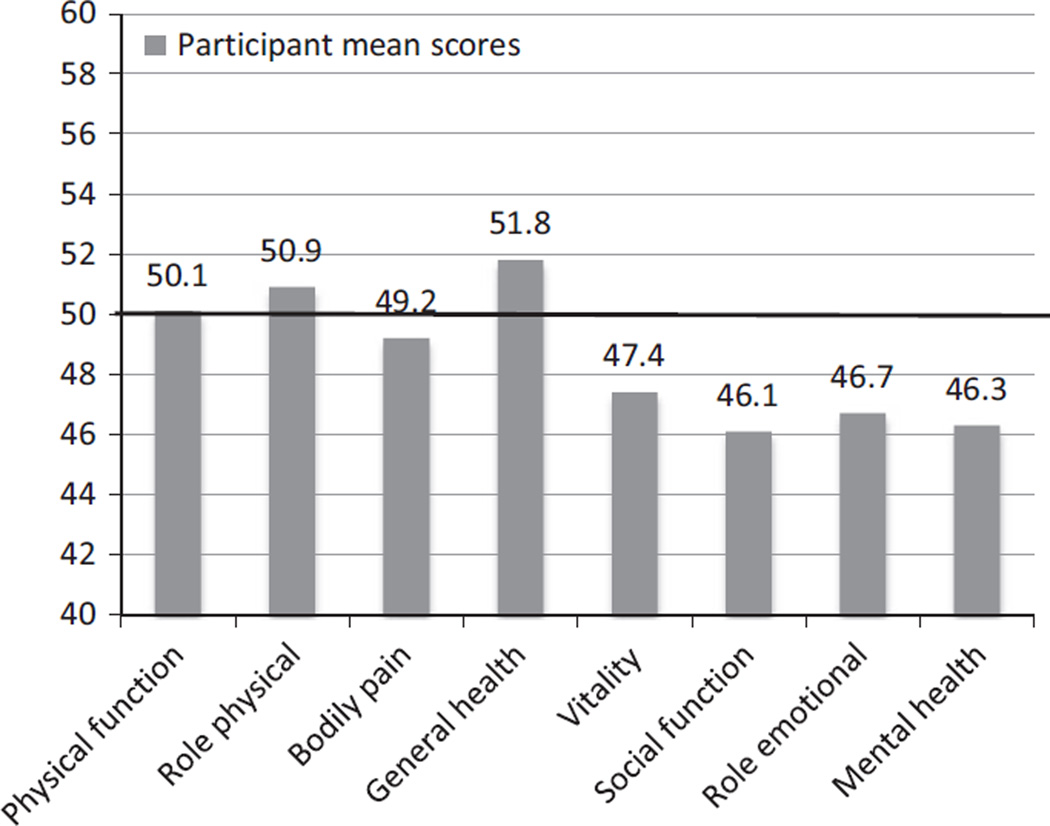

Participants met or exceeded the national average for physical functioning, ability to perform daily roles, bodily pain and general health but fell below the national average for vitality, social functioning, mental health and the ability to perform daily roles as a result of emotional well-being (see Figure 1). In a composite score generated from the physical health dimensions, 47% of participants described physical health that exceeded the population norm, 30% described health that was comparable to the population norm and 23% described health that fell below the population norm. Conversely, nearly half (46%) of participants had mental health composite scores that fell below the population norm. The SF-36 v.2 also provides a first-stage depression screening and 40% of participants screened positive for depression. Consistent with this screening metric, 49% of participants reported moderate to severe symptoms of depression using the CES-D scale.

Figure 1.

Parental physical and mental health dimensions. From SF-36v2: compared to 2009 national adult normative data. 0–100, 50 = national.

Participants were stratified by level of depression symptoms (clinical criteria for moderate to severe symptoms vs. no to mild symptoms). After excluding the few participants with missing data for depression, we compared strata across all health and well-being variables (see Table 1). In all cases, those in the depressed group reported poor health status and higher levels of perceived stress. No significant differences in the severity of depression were found based on age, duration of time as a participant in the housing-plus programme, days of work missed or days spent in bed due to health.

Table 1.

Phase 1: Comparison of parental participants with no to low depressive symptoms and moderate to severe depressive symptoms for health status and perceived stress levels

| Depressive symptoms |

N | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | No to low | 48 | 30.9 (8.0) |

| Moderate to severe | 46 | 31.2(8.6) | |

| Years in programme | No to low | 46 | 2.9 (2.5) |

| Moderate to severe | 45 | 2.5(2.1) | |

| Bed days in past year | No to low | 48 | 2.4 (6.3) |

| Moderate to severe | 46 | 4.1 (5.2) | |

| Missed work days in past year |

No to low | 48 | 2.8 (6.6) |

| Moderate to severe | 46 | 4.6 (9.5) | |

| Perceived stress* | No to Low | 47 | 15.5 (6.5) |

| Moderate to severe | 45 | 24.3 (5.1) | |

| Physical function | No to low | 49 | 84.5 (24.7) |

| Moderate to severe | 47 | 79.0 (24.8) | |

| Role performance- physical health* |

No to low | 49 | 88.9(18.4) |

| Moderate to severe | 46 | 78.0(18.7) | |

| Role performance- emotional health* |

No to low | 49 | 86.4(19.5) |

| Moderate to severe | 47 | 67.7 (25.3) | |

| Bodily pain* | No to low | 49 | 79.5 (22.9) |

| Moderate to severe | 47 | 57.9 (25.0) | |

| Vitality* | No to low | 49 | 65.1 (16.5) |

| Moderate to severe | 47 | 38.0(18.5) | |

| Social function* | No to low | 49 | 88.8(16.6) |

| Moderate to severe | 47 | 54.5 (24.5) | |

| Mental health* | No to low | 49 | 81.4 (14.3) |

| Moderate to severe | 47 | 50.4(17.3) | |

| General health perception* |

No to low | 49 | 80.6(14.8) |

| Moderate to severe | 47 | 57.9 (22.9) |

SF-36 mean scores scales 0–100, where 100 = optimal health/well-being.

P ≤ 0.05.

Children

All parent participants completed a health survey for one randomly selected child under the age of 18 years. Of these 101 surveys, data were collected for 5 children younger than 1 year of age, 19 children between the ages of 1 and 3 years, 52 children between the ages of 4 and 10, and 25 children between the ages of 11 and 17. The gender distribution for these children was 51% female and 49% male. Parents reported that 99% of children were up to date on vaccinations and had accessed healthcare services within the past year at a doctor’s office or Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) office (68%) or health clinic (25%).

Here, we only report the health status of the 77 children between the ages of 4 and 17 years because the CHQ-PF28 is only validated for this age range. Participants describe their children’s physical and emotional health status as broadly comparable to US age-adjusted population norms across multiple dimensions of physical, emotional and behavioural health (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Phase 1: Parent report of children’s health and well-being using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) and the Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ)

| N | Mean (SD) | Norm Mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| SDQ emotional symptoms | 75 | 1.7(1.8) | 1.6(1.8) |

| SDQ conduct problems | 77 | 2.0 (2.0) | 1.3(1.6) |

| SDQ hyperactivity | 77 | 3.2 (2.5) | 2.8 (2.5) |

| SDQ peer problems | 77 | 1.9(1.8) | 1.4(1.5) |

| SDQ total difficulties | 75 | 8.6 (5.9) | 7.1 (5.7) |

| SDQ prosocial behaviour | 76 | 8.1 (2.0) | 8.6(1.8) |

| CHQ physical function | 76 | 91.2 (22.9) | 95.0(16.20) |

| CHQ role of social-physical | 76 | 93.4(17.2) | 93.7(19.7) |

| CHQ bodily pain | 75 | 86.9(17.9) | 81.3(19.7) |

| CHQ role emotional | 76 | 91.7(19.0) | 92.5(19.1) |

| CHQ self-esteem | 75 | 80.2 (22.3) | 80.1 (19.1) |

| CHQ mental health | 74 | 78.50 (20.2) | 79.7(15.5) |

| CHQ Behavior | 75 | 68.4 (23.4) | 70.8(18.7) |

SDQ for all dimensions other than total difficulties scale is 0–5, total difficulties 0–20. CHQ mean scores scaled 0–100, where 100 = optimal health/well-being.

Relationship of parent and child health status

We compared children’s health and well-being for the 77 parent–child pairs (using the 77 children between the ages 4 and 17 years) by level of parental depression. Report of emotional symptoms, conduct problems, peer problems, poorer mental health and more difficulties with role performance due to emotional-behavioural health in children was significantly higher for children with parents who had moderate–severe depression symptoms when compared to parents with lower levels of depression symptoms (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Phase 1: Comparison of child’s health and well-being based on parental depression

| Depressive symptoms |

N | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child’s age | No to low | 32 | 7.94 (3.73) |

| Moderate to severe | 39 | 9.44 (4.24) | |

| SDQ emotional symptoms* |

No to low | 31 | 1.39(1.37) |

| Moderate to severe | 38 | 2.26 (2.13) | |

| SDQ conduct problems* |

No to low | 32 | 1.47 (1.88) |

| Moderate to severe | 39 | 2.44 (2.05) | |

| SDQ hyperactivity | No to low | 32 | 3.22 (2.70) |

| Moderate to severe | 39 | 3.21 (2.48) | |

| SDQ peer problems* |

No to low | 32 | 1.28(1.30) |

| Moderate to severe | 39 | 2.49 (1.97) | |

| SDQ prosocial behaviour |

No to low | 32 | 8.59(1.72) |

| Moderate to severe | 39 | 7.84 (2.15) | |

| CHQ physical function |

No to low | 32 | 89.2 (27.7) |

| Moderate to severe | 38 | 93.0(17.6) | |

| CHQ role of social-physical |

No to low | 32 | 95.8(14.1) |

| Moderate to severe | 39 | 92.1 (18.1) | |

| CHQ bodily pain | No to low | 32 | 89.4(16.1) |

| Moderate to severe | 39 | 82.6(19.8) | |

| CHQ role emotional- behavioural* |

No to low | 32 | 96.9(13.0) |

| Moderate to severe | 39 | 87.7 (21.1) | |

| CHQ self-esteem | No to low | 32 | 85.2(21.5) |

| Moderate to severe | 39 | 75.2 (23.0) | |

| CHQ mental health* |

No to low | 32 | 83.6(18.4) |

| Moderate to severe | 39 | 71.0(23.0) | |

| CHQ Behavior | No to low | 32 | 72.9 (22.2) |

| Moderate to severe | 39 | 64.8 (23.8) |

SDQ is Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; CHQ is Child Health Questionnaire-mean scores for the CHQ are scaled 0–100, where 100 = optimal health/well-being.

P ≤0.05.

Phase 1: Focus group themes

Parents

A total of 13 parents (all mothers) participated in focus groups. The most salient and consistent theme of interviews was the impact of stress on these parents’ daily lives. Participants described multiple sources of stress including: difficulty balancing the competing needs of their children, rigours of their academic requirements, financial and employment instability, parenting responsibilities, concern over the well-being of children and the effect of the immediate urban environment on their family’s physical and emotional health. Parents were asked to identify strategies they used to cope with these stressors. Strategies to reduce stress ranged from health-promoting activities like journaling and physical exercise to health-detracting behaviours like binge eating and social isolation. Parents identified several factors they believed would improve their health including: increased access to primary care services, psychological counselling and improved opportunities to develop social support networks in their daily lives. Exemplar quotes for the themes that emerged from focus group interviews are included in Table 4.

Table 4.

Major themes of parent and child focus groups

| Exemplar quotes | |

|---|---|

| Parents’ themes | |

| The stress of competing priorities | It’s a lot to juggle. Make sure that you pass all your classes, make sure your kids are alright while you are in school and trying to work full-time and part-time jobs. It’s a lot’. |

| Perceived impact of stress | ‘My hair started falling out. 1 had to get my hair cut. It started falling out. 1 couldn’t sleep. I’m still on anxiety pills. Just crazy’. |

| Influence of stress on parenting | ‘I’m stressed out. I’m irritable. I’m angry. So he’s not getting the attention he needs’. |

| Influence of the environment | It’s bad this summer. 1 made my son stay in the house. He doesn’t go anywhere without me. I’m scared to the point where 1 don’t let me children out the house unless I’m there’. |

| Immediate goals and aspirations | ‘I’m so close. And 1 want to just get my foot in the door somewhere within my field and I’m just so ready to move on. Not live paycheck to paycheck. That’s kind of what I’m doing. Try to save’. |

| Children’s themes | |

| Environmental sources of stress | The main thing that makes me stressed is when people always be fighting on our block’. |

| Perceptions of parental stress | ‘My mom’s stressed because she has all of these problems and don’t have nobody else to back her up. And she’s tired and she don’t have enough sleep. And I’m tired and 1 don’t have enough sleep’. |

| Perceptions of influence of housing-plus programme on parent |

‘My mom was always working to pay the money for the bills and everything. But now it’s a little cheaper. And she doesn’t have to work harder and all the time. She get to spend time with me because when 1 have homework 1 need somebody to sit with me and explain to me and everything so she gets to sit with me and explain my homework and 1 get better grades’. |

Children

Ten children between the ages of 7 and 17 participated in one of two focus groups. Three major themes emerged from these focus groups: environmental sources of stress, perceptions of parental stress and the influence of housing-plus programmes on parents. Children described their neighbourhood environment as an important source of stress in their daily lives which was attributed to exposure to conflict in their neighbourhood and schools, and witnessing crimes and police activity near their homes. Children also recognised their parents’ stress, and saw their parent as constantly tired and overly taxed by multiple priorities and little social support. Children interpreted the benefit of participating in a housing-plus programme by the reduction of economic demands on their parent to secure housing which permitted more parental support of their social and academic well-being (see Table 4).

Phase 2: Daily activity paths and narratives

Fourteen parent–child dyads (described in Table 5) consented to participate in the second phase of the study. In analysis of activity paths, four of the 14 parents (28.6%) felt very safe (i.e. 10 out of 10) and seven of the 15 children (50.0%) felt very safe over the entire span of the daily activities that they reported. Looked at another way, most of the 14 parents (71.4%) reported feeling that their safety was compromised (i.e. <10) to at least some degree at some point and half of the 14 children (50.0%) similarly reported feeling a loss of assured safety at some point during the day. The lowest level of safety reported by children was 3 and the lowest level of safety reported by parents was 1, signifying that they felt very unsafe.

Table 5.

Phase 2: Description of parent-child dyads (n = 14 parents and 14 children)

| Variable | Mean (SD) or % |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Parent | 33.7 (4.7) |

| Child | 11.2 (2.1) |

| Race - Black or African American | 100% |

| No. of children living in household | 2.7(1.7) |

| Duration at current address in months | 45 (39) Median 26 |

| Past 12 months worry about having sufficient money to pay rent? | |

| Always | 7.1% |

| Usually | 14.3% |

| Sometimes | 50% |

| Rarely | 14.3% |

| Never | 14.3% |

| Current relationship with child’s father | |

| Romantically involved on steady basis | 7.1% |

| Involved in an on-again/off-again relationship |

0% |

| Just friends | 28.6% |

| Hardly ever talk | 21.4% |

| Never talk | 35.7% |

| Missing | 7.1% |

| Frequency of changing plans because of childcare responsibilities | |

| Often | 14.3% |

| Sometimes | 7.1% |

| Rarely | 42.9% |

| Never | 35.7% |

| Proportion of time previous 24 hours parent felt unsafe |

2.8% (6.2%) |

| Proportion of time previous 24 hours concerned children were unsafe |

2.6% (5.0%) |

| Proportion of time child is under supervision of an adult |

89.6% (11.5%) |

| Neighbourhood Environment Scale (0–60) | |

| Parent | 10 (3.5) |

| Child | 5.9 (3.5) |

Narratives during the activity mapping illustrate the sources of the safety concerns. ‘There were drunk people around’. I have heard gunshots from home that sound like they come from around that store’. ‘…unfamiliar people were around that bus stop’. I was walking to my car, anything can happen’. And ‘there are drugs in the area and shooting happen, day or night’. The parent interviews further substantiated the effects of the environment on perception of safety. Parents in both high- and low-crime block groups (90.6% and 88.3% of parents respectively) reported never or rarely permitting children to leave the home unattended, especially during the summer when school is out of session. Parents attributed this caution to concerns about the exposure of their children to negative behavioural influences in their neighbourhoods. Children’s confinement in their homes was reflected in the daily activity paths generated with child participants.

Discussion

The findings of this exploratory study demonstrate that the majority of single parent, housing-unstable adults participating in a housing-plus programme perceived that their physical health met or exceeded US national norms. However, study results also illustrate the complexity of rnaintaining a household and housing-plus programme participation in often-violent urban neighbourhoods of Philadelphia, which may detract or challenge their mental and emotional well-being. Participants perceived significantly higher levels of stress when compared to national referents for gender, age and race. Of particular concern is that parent participants were two times more likely to screen positive for depression using the SF-36 when compared to the general population (39% vs. 18%). This was corroborated using a specific measure of depression (the CES-D), from which almost one-half of participants screened positive for clinically significant depressive symptoms.

To place these findings in context, previous studies have shown that higher levels of education predict both employment and earning potential and that single mothers who work and earn more income have lower levels of depressive symptoms (Jackson et al. 2008). Theoretically, clients served by housing-plus programmes, which provide services to support education and increase long-term income potential would be expected to have lower levels of depressive symptoms. Yet our study does not support this theoretical assumption. It is possible that it would take several years after housing stability is established to confer the benefit of income and education to psychological and emotional health. It is also possible that full-time (as compared to part-time) employment and stable employment over time is associated with improvement in mental health outcomes (Zabkiewicz 2010) and that part-time employment does not offer equivalent benefit. Without a comparison group, we are unable to assess the extent of the relationship between housing support programmes and psychological outcomes, but in urban environments like Philadelphia, more extensive study is warranted.

The burden of depression was associated with the overall health and well-being of participants. Participants with moderate and severe depressive symptoms reported significantly poorer health status in the domains of role performance, pain, vitality, social function and general health perception. Thus, strategies to reduce stress and depression are likely to improve how parents perceive their overall health. However, because our data are self-reported and cross-sectional, we are unable to differentiate the direction of the relationship between depression and health status or the extent to which depressive symptoms negatively colour all other self-report of health data.

A recent study showed that maternal employment in a US welfare-to-work programme decreased the probability of a child being in very good to excellent health, although the effect was small (Gennetian et al. 2010). In contrast, in our study, parents rated their children’s physical and mental health status at or above national norms although we could not compare mothers who worked to those who did not work, as all were required to work at least part time. When we examined children’s health status based on parental depression, we found that depressed parents were more likely to report higher levels of emotional symptoms, conduct problems and peer problems in their children. This finding is consistent with previous research demonstrating poorer mental health in children of low-income mothers who are depressed (Riley et al. 2009) and other reported associations between behavioural problems in children, higher parental stress (Spijkers et al. 2012) and the experience of living in socially disadvantaged neighbourhoods (Singh & Ghandour 2012).

Neighbourhood violence and disorder, poverty and unemployment are risk factors for depression (Ross 2000, Mair et al. 2010, 2012) and concomitantly strain the way that social support can mitigate the impact of depressive symptoms (Broussard 2010). Single, previously homeless mothers living in crime-ridden areas often choose not to interact with neighbours (Tischler 2008), and low-income women who experience psychological distress are less likely to perceive sufficient social support in their lives (Offer 2012). Lack of social support is also associated with higher levels of poor health in single mothers (Rousou et al. 2013), reinforcing the potential contribution of social support to reducing stress and improving health and well-being. Our analysis did not specifically address the relationship between neighbourhood characteristics, social support, depression and stress. However, focus group participants emphasised the importance of social support to mitigate the disadvantages of their income and housing instability; participants identified enhanced social connections as a primary strategy through which they believed they could better manage their stress.

The second phase of this study extends our understanding of the relationship between local violence exposure (crime rates) and the daily lived experiences of parent and child participants. We explored this aspect of family life because there was significant variation in crime rates surrounding different ACHa housing units and that prior study of 10- to 16-year olds in Philadelphia revealed finely tuned strategies and high levels of vigilance when navigating local neighbourhoods based on their sense of safety and well-being (Teitelman et al. 2010). The findings of this study indicate that parents restrict children’s activities because of fear of local-level neighbourhood characteristics. Parents felt compelled to prioritise their children’s safety by restricting movement beyond the home despite the potential to contribute to the physical and mental ramifications of inactivity and social isolation.

There are limitations to the applicability of this research to direct policy and programmatic intervention. This study was conducted in two contiguous neighbourhoods in Philadelphia with higher crime rates and fewer community resources than that of the larger city and thus the findings of this research should be interpreted with this in mind. Because we collected the phase 1 health status data anonymously, we were unable to link the health status findings to the location of residence. Consequently in phase 2, when we examined the daily activities of parents and children, we obtained new health data to explore its relationship with the micro-environmental crime data. In this phase of research, our study sample was too small to power quantitative analysis beyond simple description. Nonetheless, these data support the importance of future research that builds a stronger theoretical understanding of the relationship between the neighbourhood context of subsidised housing units and physical and mental health outcomes in housing-unstable families. Moreover, this research can be expanded to explore other features of the built environment like proximity to green space or mixed-use business districts that have been shown to improve crime rates, perception of safety and health in residents in urban settings.

This was a cross-sectional study of participants in a housing-plus programme and thus we were also unable to compare health status of parents and children to housing-unstable families not enrolled in such a programme. To address this limitation, we selected instruments that allowed us to compare physical and mental health to nationally established norms but it will be important to understand more about the role of the housing-plus programme in the lives of other housing-unstable families living in urban settings like Philadelphia. Similarly, our analysis cannot assess whether individual socioeconomic status or neighbourhood factors exerted greater effect on participants’ self-reported health. While some previous research demonstrates that neighbourhood deprivation has a stronger impact on health outcomes than personal poverty (Stafford & Marmot 2003), other studies have demonstrated the persistence of poorer health outcomes among people living at lower socioeconomic status in socially advantaged neighbourhoods (Sloggett & Joshi 1998). Ideally, future research will permit us to compare participants in different kinds of housing interventions across the urban landscape to elucidate the impact of individual and place-based variants in health and housing outcomes.

In sum, housing-plus programmes address some key social determinants of health, specifically, stabilisation of housing, support for educational progress and employment. Our findings indicate that parent’s physical health and children’s health status are comparable to US national norms. The proportion of parents with significant depressive symptoms and perceived stress, and the apparent negative associations with children’s health and well-being point to the need for further research and programmatic and policy interventions that support the overall health of these at-risk families.

What is known about this topic

Economic and housing distress can force families to make difficult choices between subsistence and health.

Affordable housing addresses health disparities by freeing up family income for resources and preventive healthcare expenditures and creates residential stability which can lessen stress and reduce exposure to stress-related illness and disability.

The health and well-being of low-resource, single-parent families living in violent neighbourhoods in US cities who participate in housing programmes is not well described.

What this paper adds

This study demonstrates that in low-income, single-parent families who participate in a housing support programme in an urban setting with high community violence, parent participants met or exceeded the US national average for self-reported physical health but fell below the national average across all mental health domains, including symptoms for moderate to severe depression.

Parents described high levels of stress resulting from competing priorities, financial instability, and concern for their children’s well-being and safety.

In this study, external markers of violence (crime rates) in the microenvironment of the families’ homes affected how parents and children conducted their daily activities and moved within their neighbourhoods.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the Center for Public Health Interest at the University of Pennsylvania and the Robert Wood Johnson Health & Societies Program at University of Pennsylvania and the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number F31NR0113599 (Jacoby). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We are grateful to the staff and clients of ACHIEVEability (Philadelphia, PA, USA) for their support and participation of this research.

References

- Basta LA, Richmond TS, Wiebe DJ. Neighborhoods, daily activities, and measuring health risks experienced in urban environments. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2010;71(11):1943–1950. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, Dekker M, Egerter S, Sadegh-Nobari T, Pollack C. Housing and Health. Princeton, NJ, USA: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Broussard CA. Research regarding low-income single mothers’ mental and physical health: a decade in review. Journal of Poverty. 2010;14(4):443–451. [Google Scholar]

- Burgard SA, Seefeldt KS, Zelner S. Housing instability and health: findings from the Michigan recession and recovery study. Social Science and Medicine. 2012;75(12):2215–2224. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartographic Modeling Lab. [accessed on 20/09/2013];Crimebase. 2014 Available at: www.cml.upenn.edu.

- Cohen R. The Impacts of Affordable Housing on Health: A Research Summary; Center for Housing Policy, National Housing Conference; Washington, DC. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CS, Mulroy E, Tull T, White C, Crowley S. Housing plus services: supporting vulnerable families in permanent housing. Child Welfare. 2004;83(5):509–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Lillie-Blanton M, Anthony JC. Neighborhood environment and opportunity to use cocaine and other drugs in late childhood and early adolescence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;43(3):155–161. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutts DB, Meyers AF, Black MM, et al. US housing insecurity and the health of very young children. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(8):1508–1514. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(11):1783–1789. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieden TR and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Forward: CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report – United States, 2011. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries/CDC. 2011;60(Suppl):1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennetian LA, Hill HD, London AS, Lopoo LM. Maternal employment and the health of low-income young children. Journal of Health Economics. 2010;29(3):353–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1997;38(5):581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, Meltzer H, Bailey V. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;7(3):125–130. doi: 10.1007/s007870050057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health ActCHQ. The CHQ Scoring and Interpretation Manual. Cambridge, MA: HealthActCHQ; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Henwood BF, Cabassa LJ, Craig CM, Padgett DK. Permanent supportive housing: addressing homelessness and health disparities? American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 2):S188–S192. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holl JL, Oh EH, Yoo J, Amsden LB, Sohn MW. Effects of welfare and maternal work on recommended preventive care utilization among low-income children. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(12):2274–2279. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AP, Bentler PM, Franke TM. Low-wage maternal employment and parenting style. Social Work. 2008;53(3):267–278. doi: 10.1093/sw/53.3.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Kling JR, Liebman JB. Moving to opportunity in Boston: early results of a randomized mobility experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2001;116(2):607. [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist TA. Minority Populations and Health: An Introduction to Health Disparities in the United States. Vol. 4. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lubell J. [accessed on 14/11/2014];A diamond in the rough: the remarkable success of HUD’s FSS program. FSS Partnerships. 2004 Available at: www.fsspartnerships.org.

- Lubell J, Crain R, Cohen R. Framing the Issues -The Positive Impacts of Affordable Housing on Health. Washington, DC: Center for Housing Policy; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, Katz LF, Kessler RC, Kling JR, Sanbonmatsu L. Neighborhood effects on the long-term well-being of low-income adults. Science. 2012;337:1505. doi: 10.1126/science.1224648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S. Place effects on health: how can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them? Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2002;55(1):125–139. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair C, Diez Roux AV, Morenoff JD. Neighborhood stressors and social support as predictors of depressive symptoms in the Chicago Community Adult Health Study. Health and Place. 2010;16(5):811–819. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair C, Kaplan GA, Everson-Rose SA. Are there hopeless neighborhoods? An exploration of environmental associations between individual-level feelings of hopelessness and neighborhood characteristics. Health and Place. 2012;18(2):434–439. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M, Homel R, Smith C. A meta-analysis of the effects of early developmental prevention programs in at-risk populations on non-health outcomes in adolescence. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32(4):506–519. [Google Scholar]

- Maruish ME, Kosonski M. A Guide to the Development of Certified Short Form Interpretation and Reporting Capabilities. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Maruish ME, Turner-Bowker DM. A Guide to the Development of Certified Modes of Short Form Survey Administration. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Noble KG, Houston SM, Brito NH, et al. Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents. Nature Neuroscience. 2015;18(5):773–778. doi: 10.1038/nn.3983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offer S. Barriers to social support among low-income mothers. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. 2012;32:120. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385. [Google Scholar]

- Reid KW, Vittinghoff E, Kushel MB. Association between the level of housing instability, economic standing and health care access: a meta-regression. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2008;19(4):1212–1228. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remes H, Martikainen P, Valkonen T. The effects of family type on child mortality. European Journal of Public Health. 2011;21(6):688–693. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley AW, Coiro MJ, Broitman M, Colantuoni E, Hurley KM, Bandeen-Roche K, Miranda J. Mental health of children of low-income depressed mothers: influences of parenting, family environment, and raters. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(3):329–336. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.3.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers J. An empirical study of intergenerational transmission of poverty in the United States. Social Science Quarterly. 1995;76(1):179. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE. Neighborhood disadvantage and adult depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(2):177–187. [Google Scholar]

- Rousou E, Kouta C, Middleton N, Karanikola M. Single mothers’ self-assessment of health: a systematic exploration of the literature. International Nursing Review. 2013;60(4):425–434. doi: 10.1111/inr.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey P. The intergenerational transmission of context. American Journal of Sociology. 2008;113(4):931–969. [Google Scholar]

- Singh GK, Ghandour RM. Impact of neighborhood social conditions and household socioeconomic status on behavioral problems among US children. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2012;16(Suppl. 1):158–169. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1005-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloggett A, Joshi H. Deprivation indicators as predictors of life events 1981–1992 based on the UK ONS Longitudinal Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1998;52(4):228–233. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.4.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spijkers W, Jansen DE, Reijneveld SA. The impact of area deprivation on parenting stress. European Journal of Public Health. 2012;22(6):760–765. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford M, Marmot M. Neighbourhood deprivation and health: does it affect us all equally? International Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;32(3):357–366. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tach L, Jacoby S, Wiebe DJ, Guerra T, Richmond TS. The effect of micro-neighborhood conditions on adult educational attainment in a subsidized housing intervention. Housing Policy Debate. 2016 doi: 10.1080/10511482.2015.1107118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman A, McDonald CC, Wiebe DJ, Thomas N, Guerra T, Kassam-Adams N, Richmond TS. Youth’s strategies for staying safe and coping with the stress of living in violent communities. Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;38(7):874–885. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Partnership Community Development Corporation. Haddington/Cobbs Creek 2010: A Plan for Our Future 2010. Philadelphia, PA, USA: The Partnership Community Development Corporation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tischler V. Resettlement and reintegration: single mothers’ reflections after homelessness. Community, Work and Family. 2008;11(3):243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Voigtlander S, Vogt V, Mielck A, Razum O. Explanatory models concerning the effects of small-area characteristics on individual health. International Journal of Public Health. 2014;59(3):427–438. doi: 10.1007/s00038-014-0556-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KAS, Conger RD, Wallace LE, Elder GH., Jr The intergenerational transmission of health-risk behaviors: adolescent lifestyles and gender moderating effects. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40(3):258–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabkiewicz D. The mental health benefits of work: do they apply to poor single mothers? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2010;45(1):77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]