Abstract

Background

Anxiety disorders are prevalent in youth and associated with later depressive disorders. A recent model posits three distinct anxiety-depression pathways. Pathway 1 represents youth with a diathesis to anxiety that increases risk for depressive disorders; Pathway 2 describes youth with a shared anxiety-depression diathesis; and Pathway 3 consists of youth with a diathesis for depression who develop anxiety as a consequence of depression impairment. This is the first partial test of this model following cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT) for child anxiety.

Method

The present study included individuals (N = 66; M age = 27.23 years, SD = 3.54) treated with CBT for childhood anxiety disorders 7 to 19 years (M = 16.24; SD = 3.56) earlier. Information regarding anxiety (i.e., Social Phobia (SoP), Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)) and mood disorders (i.e., Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and dysthymic disorders) was obtained at pretreatment, posttreatment, and one or more follow-up intervals via interviews and self-reports.

Results

Evidence of pathways from SoP, SAD, and GAD to later depressive disorders was not observed. Treatment responders evidenced reduced GAD and SoP over time, although SoP was observed to have a more chronic and enduring pattern.

Conclusions

Evidence for typically observed pathways from childhood anxiety disorders was not observed. Future research should prospectively examine if CBT treatment response disrupts commonly observed pathways.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, comorbidity, cognitive-behavioral therapy, evidence-based treatment

Several theoretical models have been proposed to explain the frequent comorbidity between anxiety and depression, including the tripartite model [1] and the behavioral inhibition/behavioral activation systems. [2] Recently, a multiple pathways model [3] posited that there are three distinct anxiety-depression pathways: Pathway 1 represents youth with a diathesis to anxiety that, when untreated, contributes to increased risk for depressive disorders; Pathway 2 describes youth with a shared diathesis for anxiety and depression, which develop simultaneously; and Pathway 3 consists of youth with a diathesis for depression who develop anxiety as a consequence of depression-related impairment. Evidence suggests that Pathway 1 is more common that the other pathways [3] and that different anxiety disorders evidence different pathways. For example, social phobia (SoP) and specific phobias have been more frequently shown to precede major depressive disorder (MDD), whereas MDD can precede panic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. [4]

SoP in childhood appears to be particularly associated with later depression [3] and youth SoP onset is related to increased depression severity, consistent with the Pathway 1 model. Youth with SoP may possess core risk factors, such as genetics, temperament, and parental psychopathology that may interact with interpersonal risk factors, such as loneliness and peer victimization, to increase risk for depression. [3; 5]

The relationship between SAD and depressive disorders has been studied less, and findings have been somewhat mixed. Some research suggests that the relationship between SAD and depression may be mediated by panic disorder, [3] such that youth with SAD are at increased risk for panic which in turn increases risk for depression. However, research has not consistently demonstrated a link between SAD and panic disorder. [6] The existing evidence suggests that SAD may increase risk for later depressive disorders, consistent with Pathway 1, though to a lesser degree than SoP and GAD. [3]

SoP and SAD typically precede depression, but GAD’s association with depression is different. GAD and MDD cross-predict one another more strongly than either disorder predicts itself over time. [3] That is, GAD more strongly predicts MDD over time than it predicts GAD, and MDD more strongly predicts later GAD than it does a diagnosis of MDD. Patterns of GAD-MDD cross prediction have been inconsistently observed across developmental stages, and some have argued that associations may be due to common causes or are an artifact of the diagnostic system given symptom overlap. [7] In general, the evidence supports GAD and MDD as distinct but highly related disorders, [3] consistent with Pathway 2.

Much of the research investigating pathways to disorders have been conducted in non-treated samples. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is efficacious for childhood anxiety disorders [8] and has secondary benefits on comorbid depressive symptoms. [9] Although reported follow-ups are informative, most existing follow-up durations did not follow youth through to the time in adulthood when secondary depressive disorders are most likely to emerge. The present study is the first to examine the anxiety and depressive disorders that emerge over time from specific childhood anxiety disorders in a sample of youth treated 7 to 19 years earlier with individual CBT treatment for child anxiety. Specifically, we examine SoP, GAD, and depressive disorders (i.e., MDD and Dysthymic Disorder) over time following CBT treatment in childhood for SAD, SoP, or GAD. We hypothesized that youth with SoP and GAD would evidence increased risk for later depressive disorders compared to youth with SAD, consistent with the multiple pathways model. We also examined anxiety disorders longitudinally, as this is particularly relevant to Pathway 2 of the multiple pathways model (e.g., evidence suggests GAD predicts MDD more strongly than it predicts ongoing GAD over time). We hypothesized that childhood primary anxiety disorder would confer increased risk for the same disorder over time but that for GAD this relationship would be weaker than the association between childhood GAD and depression over time.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by and conducted in compliance with the Institutional Review Board. The sample consisted of individuals (N = 66) who participated in two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating CBT for child anxiety reported by Kendall and colleagues. [9; 10] Participants in both RCTs were randomized to therapist and to treatment condition (i.e., Coping Cat program for child anxiety). Previous research has compared participants from the two RCTs on baseline characteristics and found few meaningful differences. [11] Successful treatment outcome in childhood in both samples was defined as the primary anxiety disorder at pretreatment no longer present at posttreatment. Independent evaluators (IEs) were blind to participant’s initial study treatment response.

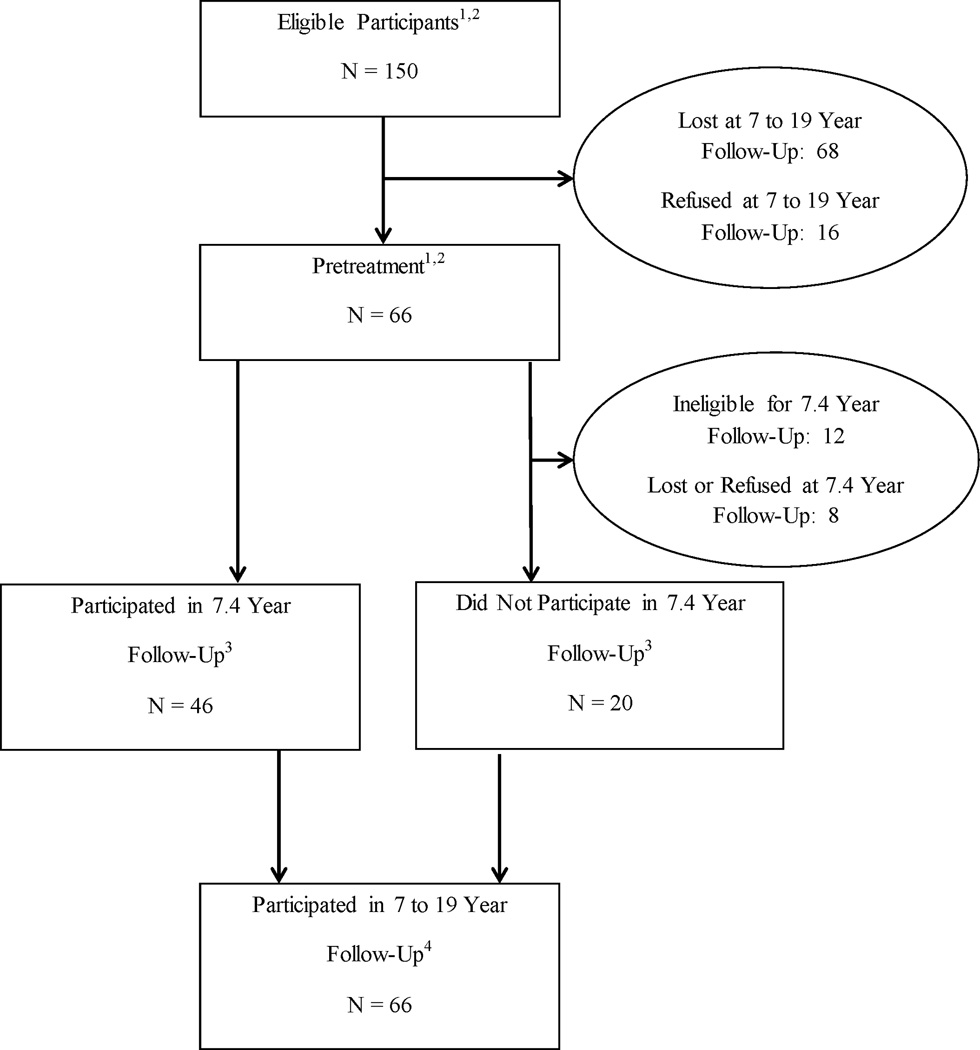

At the time of initial treatment intake for both studies, participants were aged 7 to 14. All received CBT for anxiety in childhood and completed assessments at pre- and post-treatment. At posttreatment (i.e., at the conclusion of initial study treatment in childhood), 60.6% no longer met criteria for their primary pretreatment diagnosis and were considered treatment responders. A subset of individuals (n = 46) also completed follow-up assessments an average of 7.4 years following initial treatment. [12] At the most recent 7 to 19 year follow-up (N = 66), participants had received treatment, on average, 16.24 (SD = 3.56, Range = 6.72-19.17) years prior, were a mean age of 27.23 years (SD = 3.54), 51.5% female and predominantly Caucasian (84.8%). Figure 1 illustrates how participants from the two RCTs contributed to the present sample. Of eligible participants who were located (N = 85), 77.6% participated in the 7 to 19 year follow-up.

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart illustrating participation rates at each time point.

1 Kendall PC, Flannery-Schroeder E, Panicelli-Mindel SM, Southam-Gerow MA, Henin A, Warman M. Therapy for youths with anxiety disorders: A second randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997; 65: 366-380.

2 Kendall PC, Hudson JL, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, Suveg C. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008; 76: 282-297.

3 Kendall PC, Safford S, Flannery-Schroeder E, Webb A. Child anxiety treatment: Outcomes in adolescence and impact on substance use and depression at 7.4-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004; 72: 276-287.

4 Benjamin CL, Harrison JP, Settipani CA, Brodman DM, Kendall PC. Anxiety and related outcomes in young adults 7 to 19 years after receiving treatment for child anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013; 81(5): 865-876.

Note: Participants from Kendall et al. (1997) included 94 participants who completed the initial randomized clinical trial as well as 24 additional participants who were in the intent-to-treat sample. Participants from Kendall et al. (2004), also referred to as the 7.4 year follow-up time point, were recruited from the sample of treatment completers from Kendall et al. (1997). For the most recent 7 to 19 year follow-up (i.e., Benjamin et al., 2013), participants were recruited from the entire Kendall et al. (1997) intent-to-treat sample as well as participants from Kendall et al. (2008) who (a) had been randomized to receive individual CBT and (b) were over 18 years of age at the time of recruitment for the 7 to 19 year follow-up. This resulted in an N at the 7 to 19 year follow-up of 66.

Recruitment and interview procedures, response rates, and participant demographic data from the 7 to 19 year follow-up are presented in Benjamin et al. [13] Written informed consent was obtained after participants received a complete description of the study and prior to engagement in study procedures. At 7 to 19 year follow-up, [13] fifteen (22.7%) participants reported being prescribed one or more antidepressant medication in the past 12-months and 93.9% (n = 62) of participants endorsed receiving at least some additional services (i.e., therapy or medication) since initial study treatment.

Assessment Instruments (See Table 1 for administration schedule)

Table 1.

Assessment measures by time point.

| ADIS | WHO- CIDI |

CDI | RCMAS | BDI-II | BAI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment | ● | |||||

| Posttreatment | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 7.4 Year Follow-Up |

● | |||||

| 7 to 19 Year Follow-Up |

● | ● | ● |

Note ADIS= Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule; WHO-CIDI= World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; RCMAS = Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory.

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule

At the time of initial treatment and at 7.4 year follow-up, diagnoses were determined using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children and Parents (ADIS-C/P [14]; or, in the case of the Kendall et al., 1997 trial, the previous version, the Anxiety Disorders Interview for Children [15]). The ADIS-C/P is a semi-structured interview administered separately to parents and children and queries about the symptoms, course, etiology, and severity of anxiety, mood, and externalizing disorders in youth. Diagnosticians provided a Clinical Severity Rating (CSR) on a continuous scale.1 The ADIS-C/P has demonstrated favorable psychometric properties (e.g., κ = .52 to .99) and is considered the gold-standard semistructured interview for anxiety disorders in youth. [16; 17] Consensus diagnoses, which take into account both parent and child report, were used.

For participants ages 18 and older at the time of the 7.4 year follow-up (n = 32), the Anxiety Disorders Schedule for DSM-IV, Lifetime (ADIS-IV-L [18]) adult interview was administered in lieu of the ADIS-C/P, to be consistent with participant developmental level. IEs were required to reach reliability of κ = .85 and maintained this level for both the ADIS-C/P and ADIS IV-L.

World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). [19, 20]

Diagnoses at 7 to 19 year follow-up were determined using the CIDI, a fully structured lifetime interview. Information was obtained on mood disorders, anxiety disorders, other relevant disorders, and demographic information. Diagnoses are related to independent clinical diagnoses. Retest reliability is high. [19] IEs completed a group didactic training session and independently reviewed study materials.

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI). [21]

Administered at the time of initial study treatment, the CDI is a 27-item child self-report questionnaire that assesses symptoms of depression in youth ages 7–17. Reliability and validity are acceptable. [22–24]

Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS): “What I Think and Feel”. [25]

The RCMAS, administered at the time of initial study treatment, is a 37-item self-report measure of children’s trait anxiety. Three factors are computed: Physiological Symptoms, Worry and Oversensitivity, and Social Concern-Concentration. The RCMAS has demonstrated acceptable validity and reliability. [26]

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II). [27]

Collected at 7 to 19 year follow-up, the BDI-II is a 21-item self-report measure of depressive symptoms during the past two weeks. Each item has four statements (rated from 0 to 3) with higher scores indicating greater symptomology. The psychometric properties of the BDI-II, including internal consistency, factorial validity, criterion validity, and convergent and discriminant validity are established in diverse samples. [28, 29]

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). [30]

Also collected at 7 to 19 year follow-up, the BAI is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the frequency and severity of anxiety symptoms over the past week. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale from 0 to 3 with higher scores indicating greater symptomology. The BAI has evidenced good internal consistency, retest reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity. [30, 31]

Statistical Analyses

Preliminary analyses compared 7 to 19 year follow-up participants with those unable to be contacted or unwilling to participate. Differences in initial demographic variables (i.e., age, gender) and pre- and post-treatment dependent variables (i.e., primary diagnosis, treatment response) were examined via chi-square and one-way analysis of variance tests.

Diagnostic Analyses

Given the longitudinal nature of our diagnostic data (i.e., assessments at pretreatment, posttreatment, 7.4 year follow-up, and 7 to 19 year follow-up), Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) was used to analyze diagnostic data to account for nesting of time within person. Because the outcome variables are dichotomous, a series of hierarchical generalized linear models (HGLMs) were constructed to evaluate whether specific primary anxiety and secondary depressive disorder diagnoses at pretreatment predicted anxiety and depressive disorder diagnoses over the follow-up period. Models were conducted separately for each outcome variable using full maximum likelihood with Laplace approximation procedures in HLM 7. Prior to evaluating the models that include all level-1 and level-2 predictors, we constructed unconditional growth models (i.e., outcome and level-1 variables only) to examine whether there was significant variability in the intercept (likelihood of meeting criteria for a given disorder at posttreatment) and slope (likelihood of meeting criteria for a given disorder for each year increase in age).

The level 1 equations used in these models were:

Where OutcomeDiag represents the outcome diagnosis of interest (GAD, SoP, Depressive Disorder [i.e., MDD or dysthymia] at posttreatment, 7.4-year follow-up, and 7 to 19-year follow-up)2 and Age represents participants’ age in years. The age variable was centered so that the intercept represented participants’ age at posttreatment.

The level 2 equations used in these models were:

Where Female is a dummy-coded variable representing whether a participant was female (1) or male (0); PreGADj is a dummy-coded variable representing whether participant j met criteria for GAD at pretreatment (1) or not (0); PreSADj is a dummy-coded variable representing whether participant j met criteria for SAD at pretreatment (1) or not (0); PreSoPj is a dummy-coded variable representing whether participant j met criteria for SoP at pretreatment (1) or not (0); PreDepj is a dummy-coded variable representing whether participant j met criteria for a depressive (MDD or Dysthymia) disorder at pretreatment (1) or not (0); and Responsej is a dummy-coded variable representing whether participant j responded (primary pretreatment anxiety disorder diagnosis no longer present at posttreatment) to CBT treatment (1) or not (0). All level-2 predictors were grand-mean centered to evaluate the unique contributions of each of these variables to the likelihood of meeting diagnostic criteria for a particular diagnosis over time.

Dimensional Analyses

No single measure assessing anxiety or depressive symptom severity was administered at all time-points due to changes in participant age. Thus, we were unable to use HLM and dimensional analyses were conducted using hierarchical linear regression. To determine whether severity of depressive or anxious symptoms in childhood predicted severity of depressive or anxious symptoms at 7 to 19 year follow-up, several hierarchical regressions were conducted. Age was entered into step 1. Step 2 included posttreatment CDI and one of the following variables assessing anxiety severity at posttreatment: total RCMAS scores, RCMAS worry scores, RCMAS social scores, RCMAS physical symptom scores, GAD CSR, SAD CSR, SoP CSR. The outcome variables were scores on the BDI-II and BAI at 7 to 19 year follow-up.

Results

Participation in the 7 to 19 year follow-up was not significantly associated with pretreatment primary diagnosis (χ2 (2) = 1.15, p = .56) or gender (χ2 (1) = 2.45, p = .12). Chi-square analysis comparing treatment response amongst participants versus nonparticipants in the 7 to 19 year follow-up was non-significant (χ2 (1) = 1.75, p = .19). One-way ANOVA tests comparing participants versus nonparticipants on child age was also not significant, F (1, 151) = 1.05, p = .31.

Diagnostic Analyses

The percentage of participants meeting diagnostic criteria for each disorder at each time point is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Frequencies and percentages of diagnoses at each time point.

| Diagnosis | Pretreatment n (%) |

Posttreatment n (%) |

7.4 Year Follow-Up n (%) |

7–19 Year Follow-Up N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAD | 55 (83.3%) | 21 (31.8%) | 13 (28.2%) | 6 (9.1%) |

| SAD | 28 (42.4%) | 8 (12.1%) | 1 (2.2%) | 1 (1.5%) |

| SoP | 24 (36.4%) | 19 (28.8%) | 19 (41.3%) | 8 (12.1%) |

| MDD | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (1.5%) | 6 (13.0%) | 7 (10.6%) |

| Dysthymia | 4 (6.1%) | 2 (3.0%) | 4 (8.7%) | 2 (3.0%) |

| Any Depressive | 5 (7.6%) | 3 (4.5%) | 10 (21.7%) | 9 (13.6%) |

Note GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder; SAD = Separation Anxiety Disorder; SoP = Social Phobia; MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; Any Depressive = MDD or Dysthymia

Results of the HGLM analyses are presented below and summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of HGLM models predicting specific diagnoses over time.

| GAD Diagnosis Over Time |

SoP Diagnosis Over Time |

Depressive Disorder Diagnosis Over Time |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Intercept (Posttreatment) | ||||||

| Constant | 0.36 | 0.09–1.45 | 0.27t | 0.07–1.02 | 0.02* | 0.00-0.98 |

| Female | 0.42 | 0.08–2.19 | 0.71 | 0.06–8.63 | 0.42 | 0.00–162.18 |

| Response | 0.04*** | 0.01–0.21 | 0.02** | 0.00–0.39 | 0.32 | 0.00–82.12 |

| Pre-tx GAD | 6.77 | 0.33–137.51 | 2.41 | 0.06–92.56 | 4.43 | 0.02–917.77 |

| Pre-tx SAD | 4.75 | 0.64–35.04 | 1.75 | 0.21–14.85 | 0.29 | 0.00–810.86 |

| Pre-tx SoP | 2.74 | 0.35–21.26 | 31.51* | 1.16–856.58 | 3.48 | 0.09–141.63 |

| Pre Depressive Disorder | 0.22 | 0.00– 509442.99 |

2.04 | 0.05–83.51 | 0.60 | 0.00– 1378.17 |

| Slope (Change per 1 year) | ||||||

| Constant | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 1.01 | 0.98–1.03 |

| Response | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 1.02t | 1.00–1.04 | 1.00 | 0.97–1.04 |

| Female | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 | 1.01 | 0.98–1.04 |

| Pre-tx GAD | 0.99 | 0.96–1.03 | 0.99 | 0.96–1.02 | 0.99 | 0.96–1.02 |

| Pre-tx SAD | 1.00 | 0.98–1.01 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.02 | 1.00 | 0.95–1.07 |

| Pre-tx SoP | 0.99 | 0.96–1.02 | 0.98 | 0.96–1.01 | 1.00 | 0.97–1.02 |

| Pre Depressive Disorder | 1.01 | 0.88–1.15 | 1.00 | 0.98–1.03 | 1.01 | 0.97–1.06 |

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ 0.001

Note OR = Odds Ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval for odds ratio; GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder; SAD = Separation Anxiety Disorder; SoP = Social Phobia (Social Anxiety Disorder); Depressive Disorder = Major Depressive Disorder or Dysthymia; Response = Treatment response (i.e., primary pretreatment anxiety disorder diagnosis no longer present at posttreatment) ; Pre-tx = pretreatment.

Likelihood of meeting diagnostic criteria for a depressive disorder over time following treatment

In the model predicting the likelihood of a depressive disorder over time, there were no significant predictors of the intercept or the slope.

Likelihood of meeting diagnostic criteria for GAD over time following treatment

In the model predicting the likelihood of GAD over time, individuals who responded to treatment were less likely to meet criteria for GAD at posttreatment compared to those who did not respond to treatment and regardless of individuals’ pretreatment diagnoses, OR = 0.04, p < 0.001. There were no other significant predictors of the intercept or the slope.

Likelihood of meeting diagnostic criteria for SoP over time following treatment

In the model predicting the likelihood of SoP over time, the intercept was marginally significant (OR = 0.27, p = 0.053), suggesting individuals were less likely to meet criteria for SoP at posttreatment, regardless of pretreatment diagnoses, response to CBT treatment, and gender. Additionally, individuals who responded to treatment were less likely to meet criteria for SoP at posttreatment compared to those who did not respond to treatment and regardless of the individuals’ pretreatment diagnoses, OR = 0.02, p ≤ 0.01. Individuals with a pretreatment diagnosis of SoP were significantly more likely to meet criteria for SoP at posttreatment compared to those without a pretreatment SoP diagnosis and regardless of other pretreatment diagnoses, response to CBT treatment, and gender, OR = 31.51, p < 0.05. Finally, response to treatment was marginally associated with the slope of the HGLM, suggesting individuals who responded to CBT treatment were more likely to meet criteria for SoP over time, regardless of pretreatment diagnoses and gender, OR = 1.02, p = 0.07. There were no other significant predictors of the intercept or the slope.

Dimensional Analyses

Means and standard deviations of variables used in dimensional analyses are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Means, standard deviations, and ranges of variables used in dimensional analyses.

| Variable | M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | ||

| Age (in months) | 136.54 (17.44) | 108 – 171 |

| CDI | 5.35 (6.18) | 0 – 28 |

| RCMAS total | 7.27 (6.41) | 0 – 28 |

| RCMAS social | 1.54 (1.77) | 0 – 7 |

| RCMAS worry | 3.35 (3.28) | 0 – 11 |

| RCMAS physical | 2.38 (2.29) | 0 – 10 |

| GAD CSR | 0.89 (1.39) | 0 – 4 |

| SAD CSR | 0.30 (0.84) | 0 – 3 |

| SoP CSR | 0.80 (1.36) | 0 – 4 |

| Dependent Variables | ||

| BDI-II | 10.70 (11.81) | 1 – 44 |

| BAI | 9.82 (9.78) | 0 – 31 |

Note CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; RCMAS = Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale; GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder; SAD = Separation Anxiety Disorder; SoP = Social Phobia; CSR = Clinician Severity Rating from the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory. All independent variables were collected at posttreatment. All dependent variables were collected at 7 to 19 year follow-up.

The regression predicting adult state anxiety (i.e., BAI) scores at 7 to 19 year follow-up from posttreatment childhood depression symptom (i.e., CDI) scores and posttreatment GAD severity (i.e., ADIS CSR scores) was significant, F(3, 47) = 2.69, p ≤ 0.05. Posttreatment childhood depression symptom scores were a significant predictor of adult state anxiety scores such that individuals with higher childhood depression symptom scores at posttreatment had higher adult state anxiety scores at 7 to 19 year follow-up, β = 0.38, t = 2.64, p ≤ 0.01.

Similarly, the regression predicting adult state anxiety scores from posttreatment childhood depression symptom scores and posttreatment SoP severity was significant, F(3, 47) = 2.77, p ≤ 0.05. Posttreatment childhood depression symptom scores were a significant predictor of adult state anxiety scores such that individuals with higher childhood depression symptom scores at posttreatment had higher adult state anxiety scores at 7 to 19 year follow-up, β = 0.34, t = 2.47, p < 0.05. All other regressions predicting anxiety or depression symptom severity at 7 to 19 year follow-up were non-significant.

Discussion

Following youth 7 to 19 years after they completed treatment for a child anxiety disorder allowed for a preliminary evaluation of Pathway 1 of the multiple pathways model [3] of the link between anxiety and depression. We hypothesized that youth with SoP and GAD would evidence increased risk for later depressive disorders compared to youth with SAD. These hypotheses were not supported. Evidence of pathways from SoP, GAD, and SAD to later depressive disorders, following treatment, was not observed in this sample, contrary to our predictions and previous research. [3] We also hypothesized that childhood primary disorders would confer increased risk for the same disorder(s) over time, as it is relevant to Pathway 2 if anxiety disorders predict themselves more or less strongly than they predict depressive disorders over time. Results indicated that treatment responders evidenced reduced GAD and SoP over time, although SoP was observed to have a more chronic and enduring pattern.

Evidence of pathways from SoP and SAD to later depressive disorders (i.e., MDD, dysthymia) was not observed. Similarly, GAD did not predict later depressive disorders. As Pathway 2 of the multiple pathways model [3] delineates that GAD and MDD cross predict one another over time, these results were surprising. This was contrary to our predictions and previous research. Specifically, patterns did not emerge between pretreatment anxiety disorders and later depressive disorders and this was especially of interest for SoP given its frequently documented association with later depression. [3; 32–35] The absence of an untreated comparison group precludes our ability to infer a causal effect of treatment. However, our results suggest the importance of prospective research investigating the role of CBT treatment response as a potential disruptor of commonly observed pathways.

Several significant findings emerged with respect to pathways to later anxiety disorders, particularly GAD and SoP, from childhood anxiety disorders. Regardless of pretreatment diagnosis, individuals were less likely to meet criteria for GAD as they aged, and a similar non-significant trend was observed for SoP. Treatment responders in particular were significantly less likely to exhibit GAD and SoP at posttreatment, regardless of pretreatment diagnosis. Due to the small number of youth with pretreatment SAD, we were unable to examine trends over time for youth with pretreatment SAD. One possible interpretation of these results is that treatment gains may have extended beyond reduction in symptoms related to the primary disorder that was the focus of treatment. However, the present findings are not independent evidence of treatment effects because we cannot rule out sources of internal invalidity (e.g., maturation, co-occurring outside events). If future studies replicate the present finding of a negative association between some primary childhood disorders and the same disorder in adulthood, it would be interesting to examine if that relationship can be explained by treatment factors such as magnitude of treatment response.

Individuals with pretreatment SoP were significantly more likely to meet criteria for SoP at posttreatment compared to those without SoP. Additionally, a non-significant trend suggested that treatment responders were more likely to meet criteria for SoP over time than treatment non-responders. These findings are consistent with literature suggesting SoP is more chronic and enduring. [36, 37]

Posttreatment depression symptoms scores, assessed via the CDI, predicted increased BAI anxiety symptom scores at 7 to 19 year follow-up. Models predicting BAI scores at follow-up from CDI scores at posttreatment were significant when controlling for SoP and GAD severity. This suggests that youth with more severe clinical profiles in childhood, evidenced by comorbid depression symptoms following CBT for anxiety, may remain at heightened risk for anxiety over time.

This study is strengthened by its long follow-up interval and use of gold-standard assessments. Several limitations exist. A limitation which precludes our ability to make causal inferences is the lack of comparison group. Second, the sample was primarily Caucasian and moderate to high SES. Third, the small sample size and low base rate of anxiety and mood disorders at certain time points likely limited our ability to detect significant effects, particularly if these effects were of a small to medium magnitude, and contributed to high standard errors and large confidence intervals. We believe these limitations are outweighed by the long follow up duration. Replication in larger samples is warranted before more firm conclusions can be made. Fourth, due to the sample size, we were only able to test for linear growth over the three follow-up time points. However, it is possible that the growth curves of meeting diagnostic criteria for GAD, SAD, SoP, and a depressive disorder are not linear. Future research should examine the effects of pretreatment diagnoses on diagnostic status over time using a nonlinear specification of time. Fifth, we cannot rule out the possibility that rates of comorbidity were inflated due to referral bias. Finally, because participants all had primary anxiety disorders, we did not fully test Pathway 2 or examine Pathway 3 of the multiple pathways model. [3] Future studies with large and diverse samples are needed as are studies that directly compare the multiple pathways model with other competing models such as the tripartite model [1] and the behavioral inhibition/behavioral activation systems. [2]

Conclusion

The present results have potential implications for the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders, suggesting important avenues for future research. First, evidence of pathways from SoP, GAD, and SAD to later depressive disorders was not observed in this sample, contrary to our predictions and previous research. Future research should prospectively examine if CBT treatment response disrupts commonly observed pathways. Second, youth who responded to treatment were less likely to meet criteria for GAD and SoP over time. Third, there was evidence that SoP may be chronic and enduring. Given the dearth of longitudinal research, additional studies that have the capacity to investigate the multiple pathways that may emerge from childhood anxiety disorders are needed.

Acknowledgments

PCK has received royalties from the sale of materials regarding the treatment of anxiety in youth, and his spouse has received payment from and has an interest in the publisher of these materials. SCM has received grant support from Alkermes, Forrest, Ortho-McNeil Janssen, Shire, and Sunovion. RSB has received royalties from Oxford University Press and has served as a consultant for Kinark Child and Family Services.

The initial RCTs from which participants were drawn for the present follow-up study were supported by NIMH grants to PCK (MH44042; MH64484). The design, conduct of the study, data collection and management were supported by an NIMH grant to CBW (MH086954). CBW (MH103955), MMC (MH105104), TMO (MH092603), PCK (MH86438; MH63747), and RSB (MH099179) were supported by NIMH grants during the analysis, interpretation, and preparation of the present manuscript.

Footnotes

CBW, MMC, and TMO report no competing interests.

CSRs of anxiety for participants from Kendall et al. (1997) were based on the scale of that time (0 to 4 scale). Participants from Kendall et al. (2008) were based on a 0 to 8 scale. The first author reviewed participant posttreatment diagnostic reports for participants in Kendall et al. (2008) and assigned 0 to 4 ratings for consistency.

We did not evaluate SAD as an outcome diagnosis due to a prohibitively small number of cases that met criteria for SAD at the 7.4 year follow-up (n =1) and 16-year follow-up (n = 1) assessments.

References

- 1.Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(3):316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray JA. The psychology of fear and stress. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cummings CM, Caporino NE, Kendall PC. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: 20 years after. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140(3):816–845. doi: 10.1037/a0034733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewinsohn PM, Zinbarg R, Seeley JR, et al. Lifetime comorbidity among anxiety disorders and between anxiety disorders and other mental disorders in adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1997;11(4):377–394. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(97)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epkins CC, Heckler DR. Integrating etiological models of social anxiety and depression in youth: evidence for a cumulative interpersonal risk model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Rev. 2011;14(4):329–376. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aschenbrand SG, Kendall PC, Webb A, et al. Is childhood separation anxiety disorder a predictor of adult panic disorder and agoraphobia? A seven-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(12):1478–1485. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200312000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler RC, Gruber M, Hettema JM, et al. Co-morbid major depression and generalized anxiety disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey follow-up. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(3):365–374. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverman WK, Pina AA, Viswesvaran C. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for phobic and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):105–130. doi: 10.1080/15374410701817907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kendall PC, Hudson JL, Gosch E, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: a randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(2):282–297. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kendall PC, Flannery-Schroeder E, Panichelli-Mindel SM, et al. Therapy for youths with anxiety disorders: a second randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(3):366–380. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caporino NE, Herres J, Kendall PC, Wolk CB. Dysregulation in Youth with Anxiety Disorders: Relationship to Acute and 7- to 19- Year Follow-Up Outcomes of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10578-015-0587-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kendall PC, Safford S, Flannery-Schroeder E, Webb A. Child anxiety treatment: outcomes in adolescence and impact on substance use and depression at 7.4-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(2):276–287. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benjamin CL, Harrison JP, Settipani CA, et al. Anxiety and related outcomes in young adults 7 to 19 years after receiving treatment for child anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(5):865–876. doi: 10.1037/a0033048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverman WK, Albano AM. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and Parent Versions. Boulder, CO: Graywind Publications Incorporated; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silverman WK. Anxiety Disorders Inverview for Children (ADIC) State University of New York at Albany: Graywind Publications; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silverman WK, Saavedra LM, Pina AA. Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: child and parent versions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(8):937–944. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood JJ, Piacentini JC, Bergman RL, et al. Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: child and parent versions. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31(3):335–342. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiNardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime Version (ADIS-IV-L) Albany, NY: Graywind; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(2):93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, et al. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview. An epidemiologic Instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45(12):1069–1077. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360017003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovacs M. The Children's Depression Inventory (CDI) manual. North Tonawanda, New York: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Craighead WE, Smucker MR, Craighead LW, Ilardi S. Factor analysis if the Children's Depression Inventory in a community sample. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:156–165. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timbremont B, Braet C, Dreessen L. Assessing depression in youth: relation between the Children's Depression Inventory and a structured interview. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(1):149–157. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hodges K. Depression and anxiety in children: A comparison of self-report questionnaires to clinical interview. Psychological Assessment. 1990;2(4) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. A revised measure of Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978;6:271–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00919131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynolds CR, Paget K. National normative and reliability data for Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: National Association of School Psychologists; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown G. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weeks JW, Heimberg RG. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory in a non-elderly adult sample of patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2005;22(1):41–44. doi: 10.1002/da.20068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carmody DP. Psychometric characteristics of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with college students of diverse ethnicity. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2005;9(1):22–28. doi: 10.1080/13651500510014800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck AT, Brown G, Epstein N, Steer RA. An Inventory for Measuring Clinical Anxiety - Psychometric Properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(6):893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hewitt PL, Norton GR. The Beck Anxiety Inventory: A psychometric analysis. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:408–412. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chavira DA, Stein MB, Bailey K, Stein MT. Child anxiety in primary care: Prevalent but untreated. Depression and Anxiety. 2004;20(4):155–164. doi: 10.1002/da.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Neil KA, Podell JL, Benjamin CL, Kendall PC. Comorbid Depressive Disorders in Anxiety-disordered Youth: Demographic, Clinical, and Family Characteristics. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2010;41(3):330–341. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ranta K, Kaltiala-Heino R, Pelkonen M, Marttunen M. Associations between peer victimization, self-reported depression and social phobia among adolescents: The role of comorbidity. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32(1):77–93. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tillfors M, Bassam EK, Stein MB, Trost K. Relationships between social anxiety, depressive symptoms, and antisocial behaviors: Evidence from a prospective study of adolescent boys. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23(5):718–724. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crawley SA, Beidas RS, Benjamin CL, et al. Treating Socially Phobic Youth with CBT: Differential Outcomes and Treatment Considerations. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2008;36(4):379–389. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ginsberg GS, Kendall PC, Sakolsky D, et al. Remission after acute treatment in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders: Findings from the CAMS. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychological. 2011:79806–79813. doi: 10.1037/a0025933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]