Abstract

Aim

Medulloblastoma is the most frequent malignant pediatric brain tumor. While survival rates have improved due to multimodal treatment including cisplatin-based chemotherapy, there are few prognostic factors for adverse treatment outcomes. Notably, genes involved in the nucleotide excision repair pathway, including ERCC2, have been implicated in cisplatin sensitivity in other cancers. Therefore, this study evaluated the role of ERCC2 DNA methylation profiles on pediatric medulloblastoma survival.

Methods

The study population included 71 medulloblastoma patients (age <18 years at diagnosis) and recruited from Texas Children’s Cancer Center between 2004 and 2009. DNA methylation profiles were generated from peripheral blood samples using the Illumina Infinium Human Methylation 450 Beadchip. Sixteen ERCC2-associated CpG sites were evaluated in this analysis. Multivariable regression models were used to determine the adjusted association between DNA methylation and survival. Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier curves were used to compare 5-year overall survival between hyper- and hypo-methylation at each CpG site.

Results

In total, 12.7% (n=9) of the patient population died within five years of diagnosis. In our population, methylation of the cg02257300 probe (Hazard Ratio = 9.33; 95% Confidence Interval: 1.17–74.64) was associated with death (log-rank p=0.01). This association remained suggestive after correcting for multiple comparisons (FDR p<0.2). No other ERCC2-associated CpG site was associated with survival in this population of pediatric medulloblastoma patients.

Conclusion

These findings provide the first evidence that DNA methylation within the promoter region of the ERCC2 gene may be associated with survival in pediatric medulloblastoma. If confirmed in future studies, this information may lead to improved risk stratification or promote the development of novel, targeted therapeutics.

Keywords: methylation, medulloblastoma, survival

1. Introduction

Medulloblastoma is the most common malignant brain tumor among those less than 15 years of age, affecting approximately 500 children in the United States (US) annually.1 Treatment advances and the use of multimodal therapy, often consisting of surgical resection, craniospinal radiotherapy, and cisplatin-based chemotherapy, have led to significant improvements in pediatric medulloblastoma survival over the past several decades. As a result, upwards of 70% of patients now live beyond five years of diagnosis.2 Clinical risk stratification is based on a combination of patient age at diagnosis, extent of surgical resection, and presence of metastatic disease. Patients at least three years of age, without metastatic disease, who undergo near gross-total resection (i.e., <1.5 cm2 residual tumor) are classified as average risk, while all other patients are classified as high risk. Even after accounting for clinical risk stratification, there is still significant heterogeneity in treatment outcomes for those with pediatric medulloblastoma.3 Recent advances in characterizing tumor molecular profiles have identified prognostic subgroups of medulloblastoma.4, 5 However, additional work is needed to better understand the heterogeneity that exists in treatment responses and long-term outcomes among pediatric medulloblastoma patients.

The platinum-based agent cisplatin is an important component of treatment regimens for a variety of solid tumors, including pediatric medulloblastoma. The antineoplastic activity of cisplatin is attributed to its action against cellular DNA. Cisplatin binds irreversibly to DNA through the formation of crosslinks between adjacent guanine bases, thereby disrupting mitosis and triggering apoptosis if not recognized and corrected by the cellular nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway.6, 7 Within the NER pathway is excision repair cross-complementation group 2 (ERCC2), one of nine genes involved in recognizing and repairing DNA lesions. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in ERCC2 have been associated with response to cisplatin chemotherapy or radiotherapy in osteosarcoma8, 9 and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).10–12 A recent meta-analysis further identified SNPs which conferred cisplatin resistance in lymphoblastoid cell lines through the increased expression of ERCC2.13 An increased expression of ERCC2 has been associated with platinum chemotherapy resistance in NSCLC, colon, and glioma cell lines14–16, while somatic mutations resulting in deficient ERCC2 expression have been associated with enhanced cisplatin sensitivity in urothelial carcinoma.17 Additional studies have identified associations between ERCC2 SNPs and adverse reactions to radiation therapy and cisplatin-induced toxicity in normal tissue,18, 19 suggesting ERCC2 may influence the systemic response to therapy. Based on this evidence, we hypothesized that epigenetic mechanisms likely involved in ERCC2 expression may impact treatment response and ultimately survival in pediatric medullobastoma patients.

Methylation of cytosine guanine dinucleotides (CpG sites) has emerged as an important epigenetic regulator of gene activity. Epigenetic factors, including DNA methylation, can alter the effectiveness of anti-cancer agents through their regulation of downstream gene expression.20 While there is a growing body of evidence evaluating CpG methylation using tumor-derived DNA, very little work has been done using constitutional DNA from pediatric medulloblastoma patients, which may be equally important to host treatment response.21, 22 Because recent studies suggest that peripheral tissues may serve as informative surrogates for epigenetic signatures present in complex neurologic phenotypes,23, 24 the aim of this study was to determine whether ERCC2 CpG methylation determined using peripheral blood samples was associated with 5-year overall survival among pediatric medulloblastoma patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Population

Medulloblastoma patients (N=71) who were under 18 years of age at diagnosis and had a peripheral blood sample collected at Texas Children’s Cancer Center between 2004 and 2009 were included in this study. Medical record abstraction was conducted to obtain the following demographic and clinical information: 1) date of birth; 2) date of diagnosis; 3) sex; 4) race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, or other); 5) clinical risk stratification (high or average/standard risk); 6) treatment protocol (cooperative group, multi-institutional or other);2, 25 and 7) date of death or last follow up.

2.2 Laboratory Methods

Peripheral blood samples were collected from all participants after completion of primary chemotherapy, and DNA was extracted using the Gentra blood kit (Quigen, Valencia, CA). Bisulfite treatment of extracted DNA was completed with the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). DNA methylation at CpG sites was assessed using the Illumina Infinium Human Methylation450 Beadchip array, following the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA). Preprocessing and quality control of the raw Illumina intensity files were conducted using the R Bioconductor packages ChAMP and Methylumi prior to analysis.26, 27

CpG probes with a detection p-value >0.01 in ≥ 1% of the samples or a bead count less than three in ≥ 5% of the samples were excluded. Additional filtering of probes resulted in the removal of cross-reactive probes and probes located at common polymorphic sites identified by Chen et al.28 Background correction and control normalization were performed, followed by Beta-mixture quantile normalization to further reduce Infinium type I and type II probe bias among the probes which passed the initial filtering criteria.29, 30 Possible batch effects were investigated with single value decomposition methods.31 Although evidence of batch effects was minimal, batch effect correction was accomplished using the ComBat option in ChAMP.32 Finally, cellular composition was estimated using the Houseman algorithm to permit downstream adjustment for potential differential cellular heterogeneity in blood samples (e.g., proportion of B-cells, lymphocytes, monocytes).33 The normalized, batch-corrected β-values, which measure methylation levels by calculating the ratio of methylated probe intensity to total probe intensity, for ERCC2 promoter-associated probes that passed quality control were retained for further analyses (n=16, Table 1).34

Table 1.

Location and characteristics of ERCC2 CpG sites (chromosome 19q) included in this study

| Position | Gene Feature | Relation to CpG Island | |

|---|---|---|---|

| cg07617866 | 45873294 | Body | North Shore |

| cg06245154 | 45873313 | Body | North Shore |

| cg02257300 | 45873380 | Body | Island |

| cg19995800 | 45873596 | Body | Island |

| cg03658294 | 45873700 | Body | Island |

| cg02422689 | 45873808 | 5′ UTR | Island |

| cg18475036 | 45873826 | 5′ UTR | Island |

| cg09783209 | 45873853 | TSS200 | Island |

| cg14580081 | 45873861 | TSS200 | Island |

| cg01550963 | 45873902 | TSS200 | Island |

| cg12041467 | 45873960 | TSS200 | Island |

| cg07950158 | 45874032 | TSS200 | Island |

| cg01587190 | 45874071 | TSS1500 | South Shore |

| cg27517897 | 45874080 | TSS1500 | South Shore |

| cg04878842 | 45874111 | TSS1500 | South Shore |

| cg14570121 | 45874153 | TSS1500 | South Shore |

Abbreviations: Untranslated Region, UTR; within 200 bases of transcription start site, TSS200; within 1500 bases of transcription start site, TSS1500

2.3 Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population. Specifically, the mean and standard deviation were calculated for continuous variables (e.g., age at diagnosis, survival time). Counts and percent of the total population were also determined for categorical variables (e.g., sex, race/ethnicity, risk, disease type, treatment regimen). To assess the association between methylated probes (n=16) and 5-year survival, methylation levels were assessed both as continuous and categorical variables. Linear regression models were used to evaluate the association between methylation β-values and overall survival while adjusting for covariates including age at diagnosis, sex, and race/ethnicity. Specifically, a linear regression model was generated for each ERCC2 probe where the dependent variable represented the β-value of that particular probe.34 The independent variable of interest was 5-year survival (yes or no). Therefore the delta β represents the difference in β-values between those who did and did not survive (0=survived, 1=deceased) after adjusting for key covariates. For the categorical assessment, the overall sample median of the methylation β-values at each CpG site was used to categorized individuals into “hyper-methylation” (β-values ≥ median) and “hypo-methylation” (β-values < median) groups. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) were estimated using Cox proportional hazard models, while hyper- and hypo-methylation groups were graphically compared using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank test. Regression models were adjusted for covariates which resulted in a 10% change in the estimated regression coefficient for the methylation variable. Specifically, differences in 5-year survival between those with hyper- and hypo-methylation were independently evaluated for each probe. CpG sites that were associated with 5-year survival at a p-value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. As sixteen probes were evaluated for their association with survival, the false discovery rate (FDR) was applied to account for multiple comparisons and an FDR-corrected q-value <0.20 was considered suggestive of statistical significance.35 All analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

2.4 Human Subjects Approval

Approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board for Human Subject Research for Baylor College of Medicine and Affiliated Hospitals (BCM IRB). Further approval from the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston was obtained prior to analysis.

3. Results

After all exclusion criteria were applied, 16 eligible ERCC2 CpG sites located on chromosome 19q were included in this analysis (Table 1). Two probes were located on the north shore of a CpG island, ten probes were located within the island, and four probes were located on the south shore of the island.

Most participants included in this analysis were male (73.2%, Table 2). Notably, 5-year survival in this population (88%) is consistent with previous studies of patients treated with contemporary protocols.2, 36 While there were no statistically significant differences in the demographic and treatment characteristics between survivors and deceased patients, the mean age at diagnosis was 7.2 years among survivors and 8.1 years among the deceased. Overall, 5-year survival was similar between race and ethnic groups (p-value=0.60). Among survivors, 46.8% were non-Hispanic white versus 33.3% among the deceased. Hispanics made up the largest proportion (44.5%) of the deceased population. Approximately half of the patients in both the deceased and survivor groups had standard risk tumors (55.7% and 50.0%, respectively) and most were treated according to the SJMB96/03 or CCG-9961 protocols (63.7% and 66.7%, respectively).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the Texas Children’s Hospital pediatric medulloblastoma population (N=71).

| 5-Year Survivors (N=62) | Deceased (N=9) | P-val | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at diagnosis, year(SD) | 7.2 (4.0) | 8.1 (5.3) | 0.54 |

| Sex, n(%) | 0.55 | ||

| Male | 45 (72.6) | 7 (77.8) | |

| Female | 17 (27.4) | 2 (22.2) | |

| Race/Ethnicity, n(%) | 0.60 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 29 (46.8) | 3 (33.3) | |

| Hispanic | 18 (29.0) | 4 (44.5) | |

| Other | 15 (24.2) | 2 (22.2) | |

| Risk, n(%) | 0.76 | ||

| Average/Standard | 34 (55.7) | 4 (50.0) | |

| High | 18 (29.5) | 2 (25.0) | |

| Age <3 years | 9 (14.8) | 2 (25.0) | |

| Chemotherapy Regimen, n(%) | 0.55 | ||

| SJMB96/03 or CCG-9961 | 44 (72.1) | 5 (62.5) | |

| VCR, CDDP, CTX or CCNU +/− VP-16 | 13 (21.3) | 2 (25.0) | |

| Other without these agents | 4 (6.6) | 1 (12.5) | |

| Craniospinal Radiation Dose, n(%) | 0.63 | ||

| Low (<24 Gy) | 37 (63.8) | 4 (66.7) | |

| High (≥36 Gy) | 21 (36.2) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Mean Cellular Composition, %(SD) | |||

| CD8 T cell | 8.5 (6.2) | 6.0 (4.8) | 0.24 |

| CD4 T cell | 9.4 (6.1) | 7.2 (7.4) | 0.33 |

| Natural Killer | 5.5 (5.1) | 4.1 (5.5) | 0.45 |

| B cell | 8.3 (5.0) | 6.6 (6.2) | 0.34 |

| Monocyte | 12.7 (5.4) | 13.6 (4.1) | 0.64 |

| Granulocyte | 57.3 (12.3) | 63.3 (16.8) | 0.20 |

Abbreviations: Standard Deviation, SD; P-value from t-test or Fisher’s exact test, P-val; Vincristine, VCR; Cisplatin, CDDP; Cyclophosphamide, CTX; Lomustine, CCNU; Etoposide, VP-16

Missing or incomplete information on risk (n=2), chemotherapy regimen (n=2), craniospinal radiation dose (n=7)

When comparing β values between the survivor and deceased groups, 50% (n=8) of the sixteen probes had positive delta values while the other 50% had negative values (Table 3). In this case, positive delta β values indicate that the deceased group had greater average methylation at a given probe when compared to the survivor group. Analysis of the sixteen ERCC2 probes using linear regression revealed a single significant association between 5-year survival and methylation at cg02257300 (delta β = 0.19; 95% CI: 0.02–0.35), after adjusting for age at diagnosis, gender, and race/ethnicity. The inclusion of other covariates, including clinical risk group and estimated cellular heterogeneity, did not notably impact the observed association (change in estimate <10%); therefore, these variables were not included in the multivariable models.

Table 3.

Regression results for all association between ERCC2 CpG methylation and 5-year survival among Texas Children’s Hospital pediatric medulloblastoma (N=71)

| Median β Value (%) | Delta β Value1 Mean (95% CI) | 5-Year Survival2 HR (95% CI) | FDR3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg07617866 | 11.92 | 0.39 (−2.21–2.99) | 1.23 (0.32–4.58) | 0.81 |

| cg06245154 | 3.58 | 0.13 (−0.60–0.86) | 1.24 (0.34–4.65) | 0.81 |

| cg02257300 | 1.76 | 0.19 (0.02–0.35) | 9.33 (1.17–74.64) | 0.16 |

| cg19995800 | 1.76 | 0.04 (−0.26–0.33) | 1.35 (0.36–5.02) | 0.81 |

| cg03658294 | 1.40 | 0.02 (−0.11–0.14) | 1.30 (0.35–4.84) | 0.81 |

| cg02422689 | 1.54 | −0.02 (−0.14–0.11) | 0.85 (0.23–3.18) | 0.81 |

| cg18475036 | 2.39 | −0.19 (−0.42–0.04) | 0.52 (0.13–2.06) | 0.81 |

| cg09783209 | 1.10 | −0.01 (−0.08–0.06) | 0.83 (0.22–3.09) | 0.81 |

| cg14580081 | 11.41 | 0.88 (−0.57–2.33) | 2.04 (0.51–8.19) | 0.81 |

| cg01550963 | 0.90 | −0.01 (−0.08–0.07) | 0.48 (0.12–1.92) | 0.81 |

| cg12041467 | 1.40 | −0.06 (−0.18–0.07) | 0.78 (0.21–2.92) | 0.81 |

| cg07950158 | 1.91 | 0.03 (−0.14–0.21) | 0.82 (0.22–3.05) | 0.81 |

| cg01587190 | 3.77 | −0.24 (−0.72–0.24) | 0.51 (0.13–2.04) | 0.81 |

| cg27517897 | 9.96 | 0.60 (−1.85–3.26) | 1.43 (0.38–5.32) | 0.81 |

| cg04878842 | 4.03 | −0.82 (−2.85–1.20) | 0.53 (0.13–2.10) | 0.81 |

| cg14570121 | 2.06 | −0.38 (−0.87–0.11) | 0.28 (0.06–1.36) | 0.74 |

Abbreviations: Confidence Interval, CI; Hazard Ratio, HR, False Discover Rate, FDR

Delta Beta (expected beta affected - expected beta unaffected) calculated from linear regression models adjusted for age at diagnosis, gender, and race/ethnicity

Unadjusted estimates from Cox proportional hazards models

False Discovery Rate corrected p-value from log-rank test

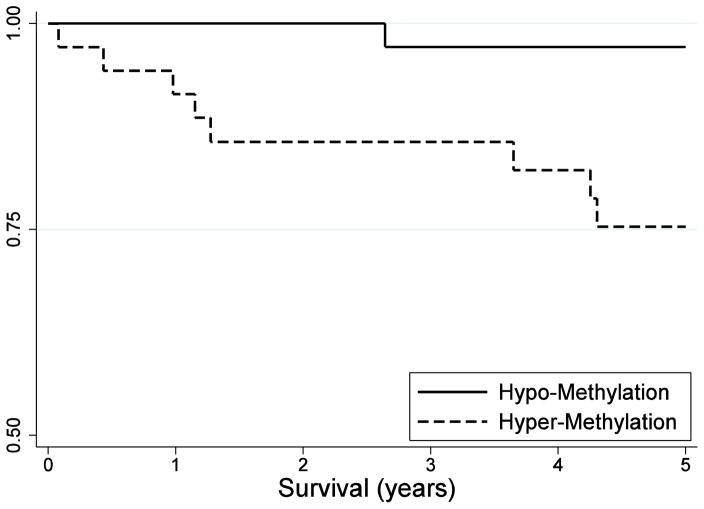

Cox proportional hazard regression was used to further evaluate differences in 5-year survival between subjects in the hyper- and hypo-methylation groups. Although possible confounders were evaluated, no variables resulted in a notable change (i.e., >10%) in the estimated methylation regression coefficient. Because the adjusted estimates were similar and the sample size was limited for this study, only unadjusted hazard ratios are presented. This analysis supported a statistically significant association between methylation at cg02257300 and 5-year survival, with the survival of the hyper-methylation group being higher than that of the hypo-methylation group (HR = 9.33; 95% CI: 1.17–74.64). No violations of the proportional hazards modeling assumptions were detected.

Log-rank comparisons of the Kaplan-Meier survival curves were consistent with previous analyses (Figure 1), with poorer overall survival associated with hyper-methylation of cg02257300 (p-value = 0.01). The observed association remained suggestive of statistical significance after accounting for multiple comparisons (FDR adjusted q-value = 0.16, Table 3). Analysis of all other probes showed no statistically significant or suggestive differences in 5-year survival between the hyper- and hypo-methylation groups (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier 5-year survival curve for hypo- (cg02257300 β <1.76%) and hyper-(cg02257300 β ≥ 1.76%) methylation at cg02257300 among Texas Children’s Hospital medulloblastoma patients (N=71)

4. Discussion

The goal of this study was to determine whether differentially methylated loci in constitutional ERCC2, a nucleotide excision repair gene, were associated with survival among pediatric medulloblastoma patients. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the relationship between ERCC2 methylation and medulloblastoma survival. Multiple analyses indicated that hyper-methylation at the cg02257300 CpG site was significantly associated with poorer survival. This relationship remained suggestive after adjusting for multiple comparisons. No other associations between methylation and survival were observed in the remaining CpG sites.

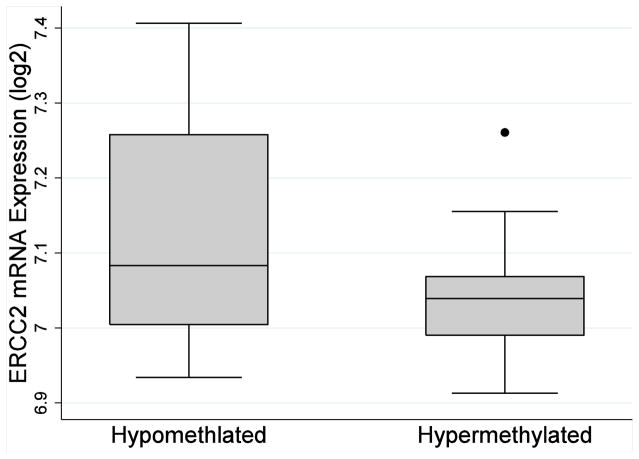

For most patients, chemotherapy using platinum-based agents is the final step in the standard course of treatment for pediatric medulloblastoma. The antineoplastic activity of platinum chemotherapy is attributed to its action against DNA, causing structural changes in the DNA helix and subsequent problems in replication and transcription. Nucleotide excision repair (NER) involves removal of these damaged DNA segments, which are usually 25–30 nucleotides in length. One essential gene in the NER pathway is the excision repair cross-complementation group 2 (ERCC2), found on the q arm of chromosome 19 and codes for the xeroderma pigmentosum group D (XPD) protein. Previous studies have identified a link between ERCC2 genetic variation and cancer risk, including breast, prostate, gastric, lung, head and neck, and esophageal cancer,37–43 as well as survival among cancers treated with platinum-based regimens.8–12 At least a portion of the association between ERCC2 and the response to platinum chemotherapy appears to be explained by differences in the expression of XPD.13 XPD expression, for example, has been associated with platinum sensitivity in NSCLC, colon, glioma, and urothelial carcinoma cell lines.14–17 Considered collectively, this evidence suggests additional factors, including epigenetics, which regulate XPD expression may also contribute to individual responses to cisplatin therapy. Consistent with this hypothesis, the results of this study showed that ERCC2 hyper-methylation is associated with reduced 5-year survival. While XPD expression data was unavailable for the patients included in this analysis, we evaluated the impact of cg02257300 methylation on ERCC2 mRNA expression using publically available Gene Expression Omnibus data (GEO accession number: GSE49065). Although not statistically significant, hypermethylation of cg02257300 was associated with reduced ERCC2 gene transcription among this sample of 20 healthy adults (Figure 2). The biologic consequence of differential methylation may be more pronounced among subjects exposed to highly genotoxic agents, such as platinum-based chemotherapy. Although additional research is needed to elucidate the mechanism by which DNA methylation may influences patient outcomes, this study provides some evidence that differential expression of genes involved in the nucleotide excision repair pathway may help to predict survival in medulloblastoma.

Figure 2.

Observed ERCC2 mRNA expression for hypomethylation (<sample median, N=10) and hypermethylation (≥ sample median, N=10) at cg02257300 among healthy adults with publically available Gene Expression Omnibus data (GEO accession number: GSE49065)

There is little evidence as to why survival varies among children diagnosed with medulloblastoma, even within clinical risk stratification groups. Currently, one of the best predictors of survival is tumor molecular subgroups, of which there are four (WNT, SHH, Group 3, and Group 4 tumors).4, 5 Wingless (WNT) tumors are characterized by abnormalities in the WNT signaling pathway and are primarily observed in older children and adults and are associated with a very good outcome.44 Sonic hedgehog (SHH) tumors are characterized by abnormalities in the sonic hedgehog signaling pathway and are most often observed in children younger than three years, adolescents, and adults and outcome is generally favorable.44 Group 3 tumors are characterized by a variety of mutations, most commonly, amplification of MYCC. These tumors, which most frequently occur in infants and children, typically have the least favorable outcome. Group 4 tumors are often associated with CDK6 amplification, MYCN amplification, and may also have an abnormality in isochrome 17q. Outcomes in this subgroup are better than those of Group 3, but relatively poor compared to WNT and SHH tumors.44

Our study must be considered in light of certain limitations. As peripheral blood samples were collected after the completion of primary chemotherapy, we cannot establish if differences in methylation existed prior to the initiation of therapy. Another limitation is that were not able to characterize the epigenetic profiles of tumor samples from patients included in this study. Although previous research suggests ERCC2 mRNA expression is highly correlated between blood and certain tumor tissue,45 direct comparison of blood and medulloblastoma methylation and gene expression profiles was not feasible in this study. Still, DNA methylation patterns appear to be highly correlated across tissues, including blood and neurologic tissue, supporting the use of peripheral tissues in epigenetic studies of neurologic phenotypes.23, 24 Also a limitation of this study, the primary event in this study (death within 5-years of medulloblastoma diagnosis) was relatively rare, limiting the statistical power of the current analysis. Future studies are needed to independently replicate the findings of this study and pair CpG methylation with gene expression among patients undergoing treatment. Finally, tumor molecular subtypes, the strongest predictors of medulloblastoma prognosis, were not analyzed in this study because they were not routinely collected on patients treated during the study recruitment period. If the ERCC2 methylation profiles identified in this study were associated with tumor subtype, it is possible that molecular subtype represents an important source of uncontrolled confounding in this analysis. Strengths of this study include the use of a relatively large, well-characterized cohort of patients exposed to largely homogeneous, contemporary treatment regimens.

5. Conclusion

In summary, this study found that hyper-methylation of the cg02257300 probe is significantly associated with decreased 5-year survival in pediatric medulloblastoma patients. Future studies using this population include conducting functional experiments to evaluate the impact of CpG methylation on gene expression and expanding the methods used in this study to other genes in the nucleotide excision repair pathway. Given the possible association between use of platinum-based agents in chemotherapy and subsequent changes in methylation,20 serial collection of peripheral blood samples, including prior to therapy, and comparing blood and tumor sample methylation profiles might yield prognostic biomarkers of survival or inform directed therapy to improve outcomes among pediatric medulloblastoma patients.

Highlights.

We evaluated the role of ERCC2 DNA methylation profiles on pediatric medulloblastoma survival

Sixteen ERCC2-associated CpG sites were evaluated 71 patients with medulloblastoma

Methylation of ERCC2 cg02257300 was associated with a poor prognosis in this population

These findings provide evidence that ERCC2 DNA methylation may impact medulloblastoma survival

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R25CA160078) and Wipe Out Kids Cancer (PI: Murray).

Abbreviations

- ERCC2

excision repair cross-complementation group 2

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- FDR

false discovery rate

Footnotes

Authorship contribution

EB, PL, and AB conceived this study. AB, SR and EP performed data collection and quality control. EB and AB produced all tables and figures. EB, PL, and AB analyzed data. EB, PL, AB, MS, SR, MC and LM interpreted findings and identified discussion points. EB drafted the manuscript, which was reviewed and modified with input from all authors over various versions. All authors saw and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors report any conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, et al. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2014;64(2):83–103. doi: 10.3322/caac.21219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gajjar A, Chintagumpala M, Ashley D, et al. Risk-adapted craniospinal radiotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy and stem-cell rescue in children with newly diagnosed medulloblastoma (St Jude Medulloblastoma-96): long-term results from a prospective, multicentre trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2006;7(10):813–820. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70867-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellison DW, Kocak M, Dalton J, et al. Definition of disease-risk stratification groups in childhood medulloblastoma using combined clinical, pathologic, and molecular variables. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(11):1400–1407. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kool M, Korshunov A, Remke M, et al. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: an international meta-analysis of transcriptome, genetic aberrations, and clinical data of WNT, SHH, Group 3, and Group 4 medulloblastomas. Acta neuropathologica. 2012;123(4):473–484. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0958-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Northcott PA, Korshunov A, Pfister SM, et al. The clinical implications of medulloblastoma subgroups. Nature reviews Neurology. 2012;8(6):340–351. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Earley JN, Turchi JJ. Interrogation of nucleotide excision repair capacity: impact on platinum-based cancer therapy. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;14(12):2465–2477. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reed E. Platinum-DNA adduct, nucleotide excision repair and platinum based anti-cancer chemotherapy. Cancer treatment reviews. 1998;24(5):331–344. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(98)90056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goricar K, Kovac V, Jazbec J, et al. Genetic variability of DNA repair mechanisms and glutathione-S-transferase genes influences treatment outcome in osteosarcoma. Cancer epidemiology. 2015;39(2):182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu ZF, Asila AL, Aikenmu K, et al. Influence of ERCC2 gene polymorphisms on the treatment outcome of osteosarcoma. Genetics and molecular research : GMR. 2015;14(4):12967–12972. doi: 10.4238/2015.October.21.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SH, Lee GW, Lee MJ, et al. Clinical significance of ERCC2 haplotype-tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms in patients with unresectable non-small cell lung cancer treated with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2012;77(3):578–584. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SY, Kang HG, Yoo SS, et al. Polymorphisms in DNA repair and apoptosis-related genes and clinical outcomes of patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with first-line paclitaxel-cisplatin chemotherapy. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2013;82(2):330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan I, Salazar J, Majem M, et al. Pharmacogenetics of the DNA repair pathways in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Cancer letters. 2014;353(2):160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wheeler HE, Gamazon ER, Stark AL, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies variants associated with platinating agent susceptibility across populations. The pharmacogenomics journal. 2013;13(1):35–43. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2011.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aloyz R, Xu ZY, Bello V, et al. Regulation of cisplatin resistance and homologous recombinational repair by the TFIIH subunit XPD. Cancer research. 2002;62(19):5457–5462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plasencia C, Martinez-Balibrea E, Martinez-Cardus A, et al. Expression analysis of genes involved in oxaliplatin response and development of oxaliplatin-resistant HT29 colon cancer cells. International journal of oncology. 2006;29(1):225–235. doi: 10.3892/ijo.29.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weaver DA, Crawford EL, Warner KA, et al. ABCC5, ERCC2, XPA and XRCC1 transcript abundance levels correlate with cisplatin chemoresistance in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Molecular cancer. 2005;4(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Allen EM, Mouw KW, Kim P, et al. Somatic ERCC2 mutations correlate with cisplatin sensitivity in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. Cancer discovery. 2014;4(10):1140–1153. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song YZ, Duan MN, Zhang YY, et al. ERCC2 polymorphisms and radiation-induced adverse effects on normal tissue: systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Radiation oncology (London, England) 2015;10:247. doi: 10.1186/s13014-015-0558-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu W, Zhang W, Qiao R, et al. Association of XPD polymorphisms with severe toxicity in non-small cell lung cancer patients in a Chinese population. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2009;15(11):3889–3895. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker EK, Johnstone RW, Zalcberg JR, et al. Epigenetic changes to the MDR1 locus in response to chemotherapeutic drugs. Oncogene. 2005;24(54):8061–8075. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heyn H, Esteller M. DNA methylation profiling in the clinic: applications and challenges. Nature reviews Genetics. 2012;13(10):679–692. doi: 10.1038/nrg3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuo T, Tycko B, Liu TM, et al. Methods in DNA methylation profiling. Epigenomics. 2009;1(2):331–345. doi: 10.2217/epi.09.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davies MN, Volta M, Pidsley R, et al. Functional annotation of the human brain methylome identifies tissue-specific epigenetic variation across brain and blood. Genome biology. 2012;13(6):R43. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith AK, Kilaru V, Kocak M, et al. Methylation quantitative trait loci (meQTLs) are consistently detected across ancestry, developmental stage, and tissue type. BMC genomics. 2014;15:145. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Packer RJ, Gajjar A, Vezina G, et al. Phase III study of craniospinal radiation therapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed average-risk medulloblastoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(25):4202–4208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris TJ, Butcher LM, Feber A, et al. ChAMP: 450k Chip Analysis Methylation Pipeline. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2014;30(3):428–430. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis S, Du P, Bilke S, et al. R package version 2.16.0. 2015. Methylumi: handle Illumina methylation data. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen YA, Lemire M, Choufani S, et al. Discovery of cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs in the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 microarray. Epigenetics. 2013;8(2):203–209. doi: 10.4161/epi.23470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Triche TJ, Jr, Weisenberger DJ, Van Den Berg D, et al. Low-level processing of Illumina Infinium DNA Methylation BeadArrays. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41(7):e90. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teschendorff AE, Marabita F, Lechner M, et al. A beta-mixture quantile normalization method for correcting probe design bias in Illumina Infinium 450 k DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2013;29(2):189–196. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teschendorff AE, Zhuang J, Widschwendter M. Independent surrogate variable analysis to deconvolve confounding factors in large-scale microarray profiling studies. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2011;27(11):1496–1505. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson WE, Li C, Rabinovic A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics (Oxford, England) 2007;8(1):118–127. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Houseman EA, Accomando WP, Koestler DC, et al. DNA methylation arrays as surrogate measures of cell mixture distribution. BMC bioinformatics. 2012;13:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siegmund KD. Statistical approaches for the analysis of DNA methylation microarray data. Human genetics. 2011;129(6):585–595. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-0993-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glickman ME, Rao SR, Schultz MR. False discovery rate control is a recommended alternative to Bonferroni-type adjustments in health studies. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2014;67(8):850–857. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rednam S, Scheurer ME, Adesina A, et al. Glutathione S-transferase P1 single nucleotide polymorphism predicts permanent ototoxicity in children with medulloblastoma. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2013;60(4):593–598. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Du H, Guo N, Shi B, et al. The effect of XPD polymorphisms on digestive tract cancers risk: a meta-analysis. PloS one. 2014;9(5):e96301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo XF, Wang J, Lei XF, et al. XPD Lys751Gln polymorphisms and the risk of esophageal cancer: an updated meta-analysis. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan) 2015;54(3):251–259. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.3256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma Q, Qi C, Tie C, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of xeroderma pigmentosum group D gene Asp312Asn and Lys751Gln and susceptibility to prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gene. 2013;530(2):309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ye W, Kumar R, Bacova G, et al. The XPD 751Gln allele is associated with an increased risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma: a population-based case-control study in Sweden. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(9):1835–1841. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yin QH, Liu C, Hu JB, et al. XPD Lys751Gln and Asp312Asn polymorphisms and gastric cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP. 2013;14(1):231–236. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.1.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J, Gu SY, Zhang P, et al. ERCC2 Lys751Gln polymorphism is associated with lung cancer among Caucasians. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 2010;46(13):2479–2484. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pabalan N, Francisco-Pabalan O, Sung L, et al. Meta-analysis of two ERCC2 (XPD) polymorphisms, Asp312Asn and Lys751Gln, in breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2010;124(2):531–541. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0863-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bowden NA. Nucleotide excision repair: why is it not used to predict response to platinum-based chemotherapy? Cancer letters. 2014;346(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schena M, Guarrera S, Buffoni L, et al. DNA repair gene expression level in peripheral blood and tumour tissue from non-small cell lung cancer and head and neck squamous cell cancer patients. DNA repair. 2012;11(4):374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]