Abstract

Antiviral therapeutics with existing clinical safety profiles would be highly desirable in an outbreak situation, such as the 2013–2016 emergence of Ebola virus (EBOV) in West Africa. Although, the World Health Organization declared the end of the outbreak early 2016, sporadic cases of EBOV infection have since been reported. Alisporivir is the most clinically advanced broad-spectrum antiviral that functions by targeting a host protein, cyclophilin A (CypA). A modest antiviral effect of alisporivir against contemporary (Makona) but not historical (Mayinga) EBOV strains was observed in tissue culture. However, this effect was not comparable to observations for an alisporivir-susceptible virus, the flavivirus tick-borne encephalitis virus. Thus, EBOV does not depend on (CypA) for replication, in contrast to many other viruses pathogenic to humans.

Keywords: alisporivir, Ebola virus, cyclophilin A, antivirals, flavivirus

The 2013–2016 emergence of Ebola virus (EBOV) in West Africa is a prime example of the need for antivirals that can be used in an outbreak situation and before the development of specific vaccines is possible. Ideally, these therapeutics would already have Food and Drug Administration approval or be in advanced experimental use in humans and therefore have an accepted safety profile. One example of a broadly acting therapeutic is ribavirin with or without treatment with type I interferon [1]. Ribavirin, a guanosine analog, is used in the combination treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and beneficial effects have been shown in infection models of viral hemorrhagic fever, including those involving EBOV, Lassa virus, and Junin virus [1–3]. However, the effects of ribavirin in animal models of EBOV infection have been modest, particularly in nonhuman primates [4], and although novel nucleoside analogs (BCX4430 and GS-5734) have shown efficacy against filoviruses in cynomolgus macaques [4, 5], a search for additional therapeutic candidates is warranted.

Another class of antivirals with demonstrated efficacy against HCV targets the host protein cyclophilin A (CypA) [6]. CypA and other cyclophilins are peptidyl-prolyl isomerases that facilitate the folding of specific host and viral proteins. Accordingly, CypA is required for replication of diverse viruses, including coronaviruses, flaviviruses, retroviruses, and influenza viruses [6]. The CypA inhibitor cyclosporine A (CspA) is immunosuppressive and has been used to treat transplant rejection. However, second-generation CspA analogues exist that are nonimmunosuppressive, the most clinically advanced of which is called alisporivir [7–9]. In addition to targeting multiple viruses, therapeutics that target host proteins, termed host-targeting antivirals, are thought to represent a higher barrier to the emergence of viral resistance as compared to directly acting antivirals [10]. Mutations associated with escape in the presence of CypA inhibitors are complex and often associated with reduced viral fitness [11, 12]. Therefore, a host-targeting antiviral like alisporivir may have advantages when used in combinations with other directly acting antivirals, such as nucleoside analogs. However, nothing is known regarding the role of cyclophilins in the replication cycle of EBOV. Hence, to determine whether EBOV requires cyclophilins for replication and therefore whether EBOV can potentially be targeted by CypA inhibitors, we examined the susceptibility of EBOV to inhibition with alisporivir in vitro, using a current EBOV strain from Guinea (Makona-GC07) and the 1976 EBOV-Mayinga prototype strain.

METHODS

Cell Culture and Reagents

A549, Vero cells (ATCC) and human hepatoma 7 (Huh7) cells (provided by Prof Micheal Gale Jr) were cultured in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (inactivated by heating at 56°C for 30 minutes; Life technologies), 1% L-glutamine (2 mM; Life technologies), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL; Life technologies) in 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator at 37°C. Cell culture–grade alisporivir and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were obtained from Novartis and Sigma, respectively.

Viruses

EBOVs and flaviviruses were propagated on Vero cells as previously described [13, 14]. For virus titrations, EBOVs and flaviviruses were titrated in serial 10-fold dilutions in triplicate across Vero E6 cell monolayers in 96-well and 24-well tissue culture plates (Corning), respectively. Following 1-hour incubation at 37°C, cells were overlayed with 1.5% carboxymethyl cellulose (Sigma) in modified Eagle's medium containing 3% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Four days after infection, cells were washed 5 times with phosphate-buffered saline and fixed with 10% formalin for 48 hours. EBOV infectivity titers were determined using an indirect immunofluorescence assay. In case of EBOV, formalin-fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) and blocked with 1% bovine serum antigen (Sigma), followed by incubation with primary antibody (poly-clonal rabbit anti-VP40 [1:500]) and then secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to FITC [1:200; Sigma]). In case of flaviviruses, formalin-fixed cells were stained with crystal violet (Sigma). For each dilution, immunofluorescent foci or plaques were counted and averaged before calculating focus-forming units (FFU) or plaque-forming units (PFU) per milliliter, respectively.

Biosafety Statement

All infections with West Nile virus (WNV) and Powassan virus (POWV) were performed under biosafety level 3 conditions; procedures with EBOV-Mayinga (1976), EBOV-Makona (GCO7 2014), tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) strain Sofjin, and Kyasanur Forest disease virus (KFDV) were performed under biosafety level 4 conditions at the Rocky Mountain Laboratories Integrated Research Facility (Hamilton, Montana). Standard operating protocols were approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee.

Cell Viability Assay

A549 and Huh7 cells were seeded in 96-well plates, and 24 hours later cells were treated with DMSO or alisporivir (0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, or 40 μM) in DMSO. Cell viability was determined using the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Assay (Promega) as per the manufacturer's protocol.

Virus Infections and Alisporivir Treatment

A549 and Huh7 cells were seeded in 12 or 24 wells plates, and 24 hours later cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 for 1 hour. Virus inoculum was replaced with complete medium containing DMSO or alisporivir (0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM) for 48 hours (for Huh7 cells infected with EBOV or TBEV and A549 cells infected with flaviviruses) or 6 days (for A549 cells infected with EBOV) prior to harvest of supernatants to quantify infectious virus.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in viral titer in the presence of DMSO and alisporivir were analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance with the Dunn multiple comparison post hoc test, using Prism 6.0. Half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50 values) were also determined using Prism.

RESULTS

We examined the antiviral activity of alisporivir against either EBOV-Mayinga (1976) or EBOV-Makona (Guinea CO7) in A549 and Huh7 cells. Replication of WNV has been shown previously to be susceptible to inhibition by cyclosporine treatment [15], and therefore we included a panel of pathogenic flaviviruses (WNV, TBEV, KFDV, and POWV) as controls. A549 and Huh7 cells were chosen because they support replication of both filoviruses and flaviviruses, and cyclosporine has been shown to suppress replication of influenza virus (a negative-strand virus), and HCV (a positive-strand virus) in these cells [16]. We performed an adenosine triphosphate (ATP)–based CellTiter-Glo Luminescent assay to test the cytotoxicity of alisporivir. No considerable changes in cytotoxicity (≤80% cell viability) were observed when A549 and Huh7 cells were incubated with alisporivir at ≤5 μM for 2 days (Figure 1A and 3A) or 6 days (Figure 1B), and cell growth occurred in this time frame in the presence of ≤10 μM alisporivir.

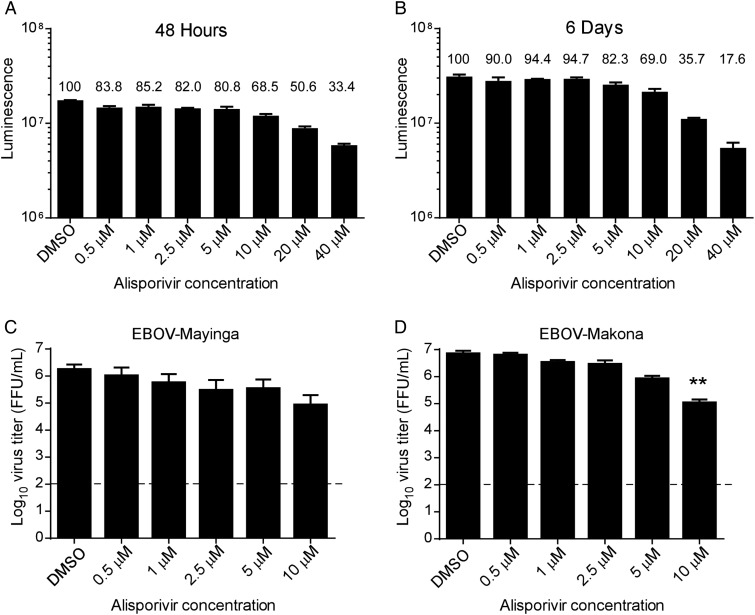

Figure 1.

Adenosine triphosphate assay assessing the viability of A549 cells following treatment with alisporivir for 48 hours (A) or 6 days (B). The luminescence values are shown with the percentage viability indicated above each bar as compared to treatment with vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) alone. C and D, Virus titers 6 days after infection in Vero cells infected with Ebola virus (EBOV)–Mayinga (C) or EBOV-Makona (D). Cells were infected with virus for 1 hour, followed by treatment with vehicle alone (DMSO) or alisporivir at the indicated concentrations. Supernatants were harvested at 6 days after infection for titration. Error bars represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. The dashed line indicates the limit of detection. **P < .01. Abbreviation: FFU, focus-forming units.

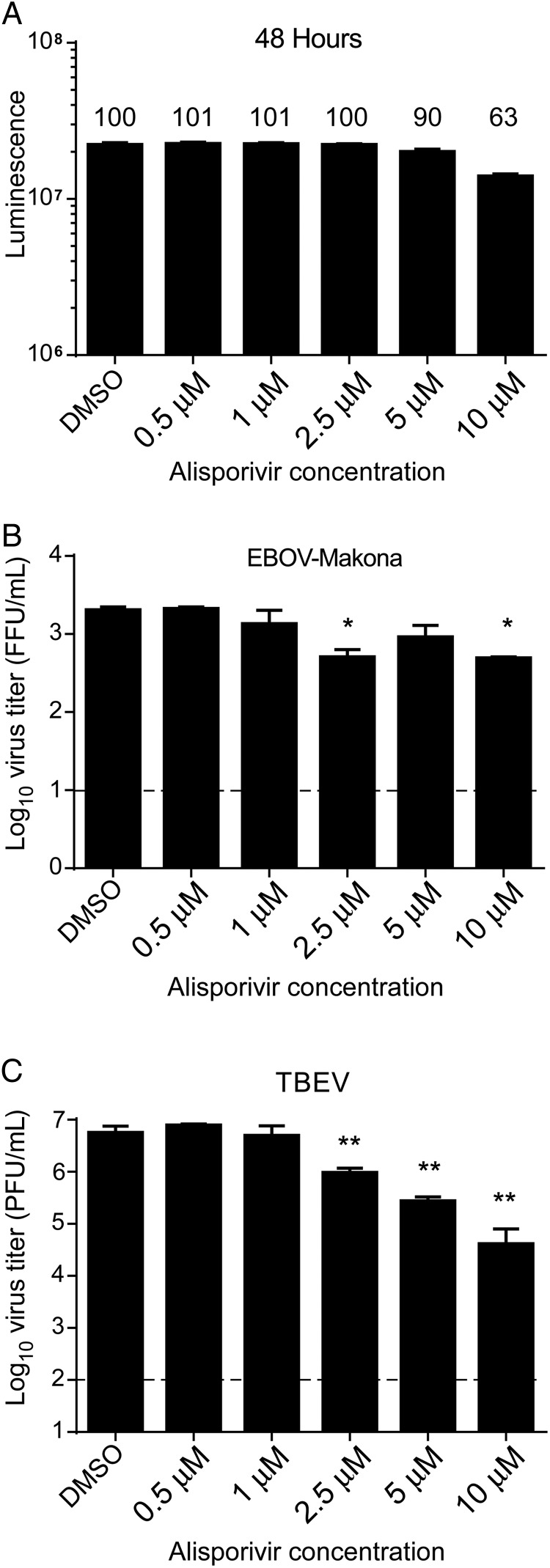

Figure 3.

Cell viability and virus titers at 48 hours in Huh7 cells. A, Adenosine triphosphate assay in Huh7 cells following treatment with alisporivir for 48 hours. The luminescence values are shown with the percentage viability indicated above each bar as compared to treatment with vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) alone. Virus titers 48 hours after infection in Huh7 cells infected with Ebola virus (EBOV)–Makona (B) or tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) strain Sofjin (C) and treated with alisporivir beginning 1 hour after infection. Error bars represent mean ± SD from triplicates from a single experiment. The dashed line indicates the limit of detection. *P < .05 and **P < .01. Abbreviations: FFU, focus-forming units; PFU, plaque-forming units.

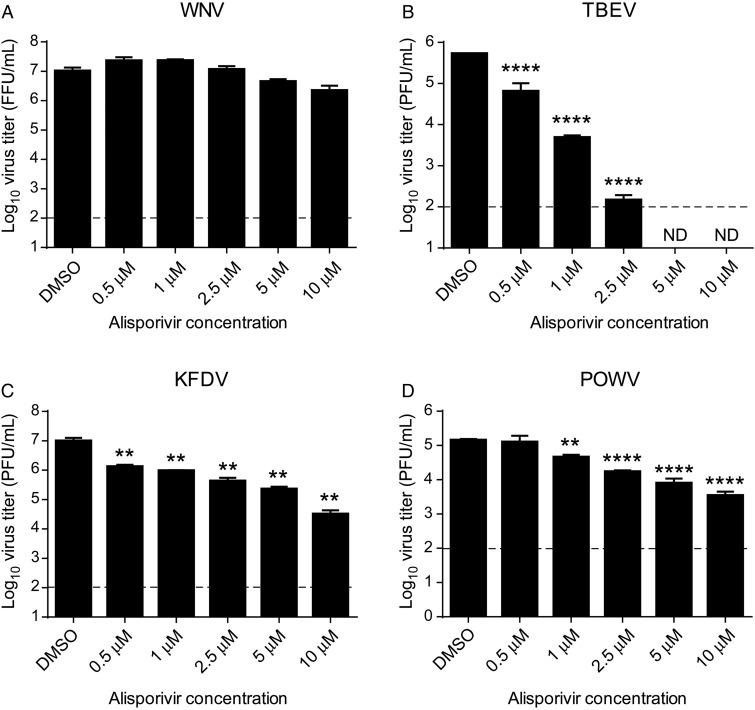

A549 cells were infected with EBOV or flaviviruses at a MOI of 0.01 and treated with alisporivir (0.5–10 μM). Virus titers from supernatants were determined at peak virus replication, which was 6 days after infection with EBOV-Makona or EBOV-Mayinga (Figure 1C and 1D) or 48 hours after infection with WNV, TBEV, KFDV and POWV (Figure 2). Significant inhibition of replication of EBOV-Makona but not EBOV-Mayinga was observed with 10 μM alisporivir. Similar results were observed if alisporivir was replenished in the medium every 48 hours for up to 9 days of infection (data not shown). This degree of susceptibility was greater than that for WNV, which only exhibited slightly reduced replication in the presence of 10 μM alisporivir, suggesting that reduced cell viability at 10 μM did not significantly influence virus replication. In contrast, the tick-borne flaviviruses, TBEV, KFDV, and POWV, all demonstrated considerable susceptibility to alisporivir treatment, with TBEV reduced by approximately 1 log10 in the presence of 0.5 μM alisporivir and by >3 log10 in the presence of 2.5 μM. To rule out cell type–specific effects, we further validated the antiviral properties of alisporivir in Huh7 cells, which can support both filovirus and flavivirus replication. Huh7 cells were infected with EBOV-Makona and TBEV at a MOI of 0.01 and treated with alisporivir (0.5–10 μM) for 48 hours after infection. Upon determining virus titers from supernatants, we observed a modest antiviral effect on EBOV-Makona at 2.5 or 10 μM alisporivir (Figure 3B). However, alisporivir elicited a potent and dose-dependent inhibition of TBEV replication beginning at 2.5 μM (Figure 3C). Taken together, these results suggest that replication of EBOV is only inhibited in the presence of relatively high concentrations of alisporivir and is demonstrably less susceptible than other viruses, particularly the tick-borne flaviviruses.

Figure 2.

Virus titers at 48 hours after infection in Vero cells infected with West Nile virus (WNV; A), tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) strain Sofjin (B), Kyasanur Forest disease virus (KFDV; C), or Powassan virus (POWV; D) and treated with alisporivir beginning 1 hour after infection. Error bars represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. The dashed line indicates the limit of detection. **P < .01 and ****P < .0001. Abbreviations: DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; FFU, focus-forming units; ND, not detected; PFU, plaque-forming units.

DISCUSSION

CypA has important roles in the replication cycles of a broad range of viruses, including influenza virus, severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronaviruses, human immunodeficiency virus, and HCV [6]. Here we examined the potential for CypA involvement in EBOV replication by treatment of EBOV-Makona– or EBOV-Mayinga–infected cells with the most clinically advanced inhibitor of CypA, alisporivir [9]. Alisporivir significantly reduced the replication of EBOV-Makona at the highest concentration tested. Although cells treated with 10 μM alisporivir exhibited some cytotoxicity as measured by cellular ATP levels, cells continued to proliferate under this concentration, and differences in the susceptibility of EBOV-Makona and EBOV-Mayinga were observed. Thus, cyclophilin inhibition has modest effects on the replication of EBOV strains. The susceptibility of EBOV-Mayinga to alisporivir was greater than that of a flavivirus previously reported to require CypA for replication, WNV [15], with IC50 values of 0.65 μM and 2.529 μM, respectively. The clinical dosing of humans who have HCV infection with alisporivir at 1000 mg/day leads to a bioavailability of approximately 1000–5000 μg/L in the serum (approximately 0.8–4 μM) [9]. Thus, inhibitory concentrations of alisporivir required to suppress EBOV replication may be achievable in a therapeutic setting. Moreover, addition of alisporivir to other promising antiviral compounds may have some benefit. However, the replication of EBOV-Makona was only reduced by a maximum of 1 log10 at 10 μM in tissue culture, which is approaching overt cellular cytotoxic levels (observed at 20 μM), and the susceptibility of EBOV strains to alisporivir was far less than that of a number of flaviviruses tested here or of HCV, which has IC50 values in the low nanomolar range [17]. Hence, these results are modest and suggest that alisporivir is not a promising therapeutic for EBOV infection.

In contrast to the findings with EBOV, alisporivir treatment resulted in a significant reduction in replication of multiple tick-borne flaviviruses, with TBEV (strain Sofjin) exhibiting the highest susceptibility. In addition, TBEV remained susceptible if alisporivir was added to cultures at 24 hours after infection, well after virus replication is established (data not shown). This work demonstrates that cyclophilins are likely important host factors for TBEV replication, whereas our data do not support a dominant role for cyclophilins in EBOV replication. It was surprising that we did not observe a greater effect of alisporivir on WNV, given previous findings. However, the previous studies used Huh-7.5 cells and required 20 μM alisporivir to observe reductions in virus titer of >10-fold [15]. The cell type used could affect the findings as the importance of CypA in virus replication can be cell-type specific, or the general resistance of the cell line to cytotoxic effects of alisporivir may be lower for A549 cells. Nevertheless, this work suggests that testing of alisporivir in the mouse model of TBEV-induced neurological disease is warranted as a potential therapeutic against this group of emerging viruses.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Novartis Pharma (Basel, Switzerland) for providing alisporivir.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Westover JB, Sefing EJ, Bailey KW et al. Low-dose ribavirin potentiates the antiviral activity of favipiravir against hemorrhagic fever viruses. Antiviral Res 2016; 126:62–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfson KJ, Worwa G, Carrion R Jr., Griffiths A. Determination and therapeutic exploitation of ebola virus spontaneous mutation frequency. J Virol 2015; 90:2345–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olschlager S, Neyts J, Gunther S. Depletion of GTP pool is not the predominant mechanism by which ribavirin exerts its antiviral effect on Lassa virus. Antiviral Res 2011; 91:89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warren TK, Wells J, Panchal RG et al. Protection against filovirus diseases by a novel broad-spectrum nucleoside analogue BCX4430. Nature 2014; 508:402–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warren TK, Jordan R, Lo MK et al. Therapeutic efficacy of the small molecule GS-5734 against Ebola virus in rhesus monkeys. Nature 2016; 531:381–5doi:10.1038/nature17180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frausto SD, Lee E, Tang H. Cyclophilins as modulators of viral replication. Viruses 2013; 5:1684–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sweeney ZK, Fu J, Wiedmann B. From chemical tools to clinical medicines: nonimmunosuppressive cyclophilin inhibitors derived from the cyclosporin and sanglifehrin scaffolds. J Med Chem 2014; 57:7145–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guedj J, Yu J, Levi M et al. Modeling viral kinetics and treatment outcome during alisporivir interferon-free treatment in hepatitis C virus genotype 2 and 3 patients. Hepatology 2014; 59:1706–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen TH, Mentre F, Levi M, Yu J, Guedj J. A pharmacokinetic-viral kinetic model describes the effect of alisporivir as monotherapy or in combination with peg-IFN on hepatitis C virologic response. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2014; 96:599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bekerman E, Einav S. Infectious disease. Combating emerging viral threats. Science 2015; 348:282–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qing J, Wang Y, Sun Y et al. Cyclophilin A associates with enterovirus-71 virus capsid and plays an essential role in viral infection as an uncoating regulator. PLoS Pathog 2014; 10:e1004422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ylinen LM, Schaller T, Price A et al. Cyclophilin A levels dictate infection efficiency of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid escape mutants A92E and G94D. J Virol 2009; 83:2044–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marzi A, Robertson SJ, Haddock E et al. EBOLA VACCINE. VSV-EBOV rapidly protects macaques against infection with the 2014/15 Ebola virus outbreak strain. Science 2015; 349:739–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor RT, Lubick KJ, Robertson SJ et al. TRIM79alpha, an interferon-stimulated gene product, restricts tick-borne encephalitis virus replication by degrading the viral RNA polymerase. Cell Host Microbe 2011; 10:185–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qing M, Yang F, Zhang B et al. Cyclosporine inhibits flavivirus replication through blocking the interaction between host cyclophilins and viral NS5 protein. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53:3226–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamamoto I, Harazaki K, Inase N, Takaku H, Tashiro M, Yamamoto N. Cyclosporin A inhibits the propagation of influenza virus by interfering with a late event in the virus life cycle. Jpn J Infect Dis 2013; 66:276–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chatterji U, Garcia-Rivera JA, Baugh J et al. The combination of alisporivir plus an NS5A inhibitor provides additive to synergistic anti-hepatitis C virus activity without detectable cross-resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:3327–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]