Abstract

Calotropis procera is a medicinal plant of immense importance due to its pharmaceutical active components, especially cardiac glycosides (CG). As genomic resources for this plant are limited, the genes involved in CG biosynthetic pathway remain largely unknown till date. Our study on stage and tissue specific metabolite accumulation showed that CG’s were maximally accumulated in stems of 3 month old seedlings. De novo transcriptome sequencing of same was done using high throughput Illumina HiSeq platform generating 44074 unigenes with average mean length of 1785 base pair. Around 66.6% of unigenes were annotated by using various public databases and 5324 unigenes showed significant match in the KEGG database involved in 133 different pathways of plant metabolism. Further KEGG analysis resulted in identification of 336 unigenes involved in cardenolide biosynthesis. Tissue specific expression analysis of 30 putative transcripts involved in terpenoid, steroid and cardenolide pathways showed a positive correlation between metabolite and transcript accumulation. Wound stress elevated CG levels as well the levels of the putative transcripts involved in its biosynthetic pathways. This result further validated the involvement of identified transcripts in CGs biosynthesis. The identified transcripts will lay a substantial foundation for further research on metabolic engineering and regulation of cardiac glycosides biosynthesis pathway genes.

Calotropis procera (Aiton) Dryand is a wild, flowering perennial shrub of family Apocynaceae1. It is indigenous to Africa and Asia and naturalized in Australia, Central and Southern America, and the Caribbean island2. In traditional Indian medicinal system, Calotropis is known to cure diseases like leprosy3, ulcers4, piles5, malaria6, snake bite7 and several other ailments of spleen and liver8. Aqueous extract of flower has analgesic9, antipyretic10, anti-inflammatory activity11, spermicidal activities12,13 and anti-fungal properties14. Recently, these have been rediscovered for their anti-cancer activities in different cancer types15. Aqueous extract of Calotropis procera latex showed protective effects against hepatocarcinogenesis without any harmful effects in treated animals16. Van Quaquebeke reported that a hemi-synthetic derivative (2-Oxovorucharin) isolated from root barks of C. procera had a strong in vitro cytotoxic effect on several human cancer cell lines17. Likewise root extracts of C. procera has been shown to inhibit proliferation of Hep-G2 cells through apoptosis and cell cycle disruption based mechanism18. Both in vitro and in vivo growth inhibition of human cancer cell lines by latex proteins from Calotropis procera have been studied by Oliveria group19. C. procera biological activities are attributed to a diverse class of compounds predominately present in form of cardiac glycosides20,21,22, terpenes23, flavonoids24 and tannin25 etc. Many cardiac glycosides have been isolated from Calotropis procera like Calactin, Ascelpin, Calotropin, Uscharin, Calotoxin, Uscharidin, Frugoside, Voruscharin26,27,28,29. These are known to specifically inhibit the plasma membrane Na+/K+ ATPase30 and have been used in congestive heart failure diseases for decades31,32.

Cardiac glycosides are characterized by the presence of core steroidal rings with its rings connected cis-trans-cis, possessing a 14β-hydroxyl group, and substituted at C-17β with a lactone ring that constitute aglycone or genin part of cardiac glycosides. At position 3β, a sugar side chain with up to five carbohydrates units is attached which forms glycone part33,34. The functional groups and sugars attached to the genin unit impart structural diversity of these compounds35. These compounds are present in different plant groups and have been well characterized for its chemical structures, but biosynthesis of these compounds have not been studied well till date36,37. A putative but partial pathway has been derived from precursor feeding studies in Digitalis lantana indicating that steroidal framework of cardiac glycosides is derivative of terpenoids, which is supposed to be formed from either mevalonic acid or 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate. Incorporation of 14C-mevalonic acid into steroid part of Digitoxin suggests that it might be the preferred route for formation of genin unit38. But contradictory studies do exist postulating that pregnane condensation with acetyl CoA or malonyl CoA, yields cardenolide genin unit39. It is suggested that several phytosterols like cholesterol, sitosterol, and stigmasterol can also be metabolized to Pregnenolone, which are thought to be first dedicated step towards cardiac glycosides synthesis. However, evidences regarding involvement of one particular phytosterol (either cholesterol, sitosterol, stigmasterol) and related steroid-backbone biosynthetic genes are still a puzzle to solve40,41.

Once pregeneolone is formed, it is reduced to Progesterone by action of Hydroxy steroid dehydrogenase (HSD) enzyme42. Reduction of Progesterone to Pregnanolone is then catalyzed by Progesterone beta reductase (PBR)43. Since cardiac glycosides structures are composed of several hydroxyl groups, it is thought to be the result of direct hydroxylation reaction catalyzed by different Monoxygenases. Enzymes involved in the Pregnane hydroxylation during formation of cardiac glycosides have not yet been identified/characterised44,45. Apart from this linear pathway described above, Maier et al. described an alternative “norcholanic acid pathway” for cardiac glycoside biosynthesis in Digitalis46. Kreis et al. suggested norcholanic acid pathway as precursor funnelling system at final stages of cardenolide biosynthesis47. 5β-POR and 3β-HSD which have a well-established role in pregnane pathway were also able to catalyse norcholanic acid and their intermediates48,49.

As cardiac glycosides compounds have limited natural abundance and there is no successful scheme for their total chemical synthesis50, an alternative method for CGs biosynthesis and enrichment is required to meet the raising global demand. Calotropis procera have more structurally diverse cardiac glycosides when compared to Digitalis, so it’s important to elucidate the biosynthetic pathway from C. procera to gain better insight of the process. For the first time, we have studied the accumulation of different CGs in stage and tissue specific manner and identified the putative genes involved in its biosynthesis. Based on the present information and taking leads from the data obtained from KEGG analysis we postulated a putative CG biosynthesis pathway in Calotropis. Information regarding the genes or enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of CGs will be very useful for establishing alternate strategies for its increased production.

Results

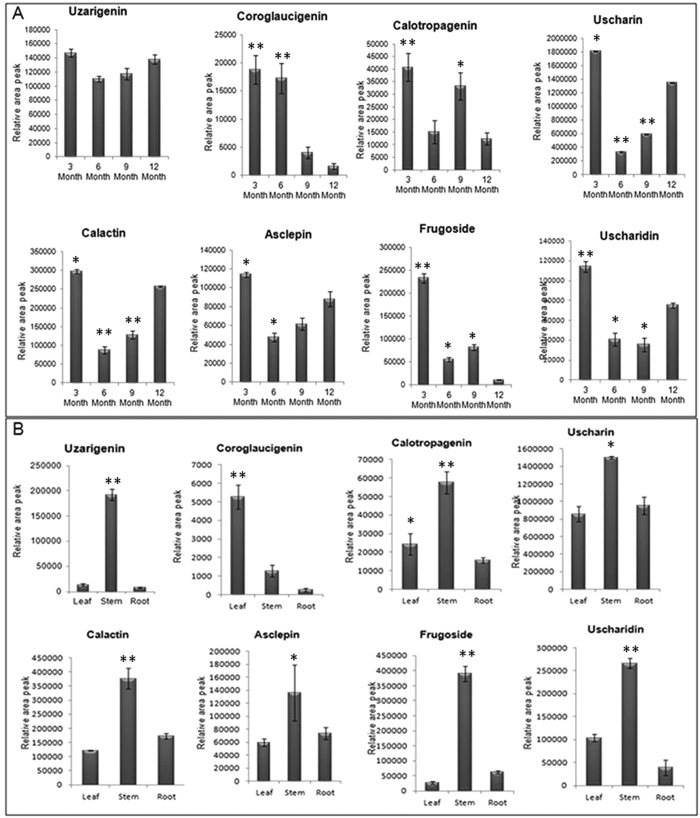

Cardiac Glycoside profiling at different developmental stages

CG identification and analysis in 3 month old C. procera seedlings was carried out using previously established LC-MS/MS method51,52. Five CGs and three genins viz. Uscharidin (530), Calactin (532), Frugoside (536), Uscharin (586), Asclepin (574), Uzarigenin (374), Coroglaucigenin (390) and Calotropagenin (404) were relatively quantified based on their area peaks in 3, 6, 9, 12 month of plant (Supplementary Table 1). Genin units showed different accumulation patterns as Uzarigenin was almost equally accumulated throughout in all development stages, while maximum accumulation of Calotropagenin and Coroglaucigenin was observed in 3 month old plant seedlings (Fig. 1A). All the five CGs showed maximum accumulation in 3 month old seedlings followed by 12- month plant except for Frugoside whose accumulation was more in 9 month old plants (Fig. 1A). To further explore the metabolite accumulation pattern, tissue specific CG profiling was done in 3 month old seedling. All the CGs and their respective genin units were accumulated more in the stem tissue when compared to root and leaf tissues (Fig. 1B). However, a considerable amount of CGs were observed in the root and leaf tissues (Fig. 1B). Based on CG profiling data, 3 month old whole seedlings were selected for transcriptome sequencing and analysis.

Figure 1.

(A) Accumulation of CGs and genin units at different stage of C. procera plant measured with LC-MS/MS. (B) Tissue-specific Accumulation profiling of CGs and genin units in C. procera plant measured with LC-MS/MS. Each value is the mean of three replicates, and error bars indicate SDs. Asteriks *(P < 0.05) and **(P < 0.001) indicate significant differences as determined by Student’s t test. (M + H)+ denote parent ions of different CGs as Uzarigenin (375), Coroglaucigenin (391) Calotropagenin (405), Uscharidin (531), Calactin (533), Uscharin (586), Frugoside (537) and Ascelpin (575).

Transcript sequencing and its de novo assembly

Transcriptome sequencing of 3 month old C. procera whole seedling was carried out and a total of 93609100 raw reads having average length of 100 nucleotides were obtained. After stringent quality assessment and data filtering, 90598670 high quality reads with base quality greater than 30 were selected for further analysis. A comparative summary statistics of the transcriptome sequencing and assembly is shown in Table 1. De novo assembly of the raw reads was done using Velvet and Oases-0.2.08 assembler programs at various k-mers and it was concluded that hash length “59” (k-mer) showed better assembly in terms of total number of contigs generated, maximum contig length, total contig length and less number of N’s. Using Velvet assembler, reads were mapped into contigs set through fragmented assembly. A total of 75530165 (83.4%) of high quality reads (Hash length = 59, N50 value = 1402) were assembled by using Velvet, and 84423412 (93.2%) raw reads (Hash length = 59, N50 value = 2574) were assembled by using Oases-0.2.08. A total of 41549 contigs with average length 730.4 base pair was obtained using Velvet (Table 1), whereas Oases-0.2.08 assembled 53256 contigs with an average length of 1903.2 (Table 1). The number of contigs and their average length was more in case of Oases-0.2.08 assembler when compared to Velvet assembler. Final contigs were clustered via CD-HIT- EST to obtain 44074 singletons (unigenes) (Hash length = 59, N50 value = 2457). The majority of unigenes ranged from 1001 to 2000 base pair (Supplementary Figure S1) with an average length of 1785 base pairs. Sequences generated from the library have been deposited in National Centre for Biotechnology Information Short Read Archive (SRA) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/) with accession no. SRR1554320.

Table 1. Transcriptome de novo Assembly Statistics of Calotropis procera.

| Sample Name | C. procera | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tool used | Velvet | Oases | Cd-hit-est |

| Hash length | 59 | ||

| Contigs Generated | 41549 | 53256 | 44074 |

| Maximum Contig Length | 13530 | 15838 | 15838 |

| Minimum Contig Length | 117 | 200 | 200 |

| Average Contig Length | 730.4 | 1903.2 | 1785 |

| Total Contigs Length | 30348668 | 101357782 | 78672233 |

| Total Number of Non-ATGC Characters | 33422 | 87231 | 72447 |

| Percentage of Non-ATGC Characters | 0.11 | 0.086 | 0.092 |

| Contigs > 100 b | 41549 | 53256 | 44074 |

| Contigs > 200 b | 29565 | 53256 | 44074 |

| Contigs > 500 b | 17854 | 45454 | 36672 |

| Contigs > 1 Kb | 10033 | 37786 | 29917 |

| Contigs > 10 Kb | 7 | 73 | 45 |

| N50 value | 1402 | 2574 | 2457 |

| No. of Reads Used | 75530165 | 84423412 | 84423412 |

| Total no. Of reads | 90598670 | 90598670 | 90598670 |

| % of reads assembled | 83.36785 | 93.18 | 93.18 |

Transcriptome annotation and Functional classification

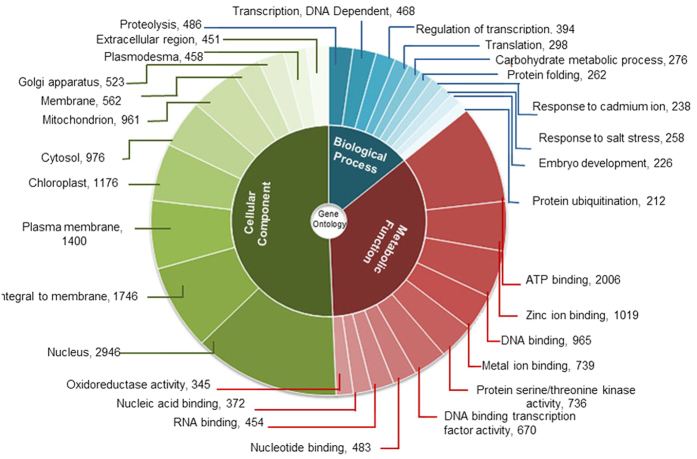

For the functional annotation of the assembled unigenes, sequence similarity search against known protein sequence datasets (NCBI non redundant (nr), UniPROT protein database and Pfam databases) was done using BLASTx program. The result indicated that 29356 (66.6%) unigenes had significant matches in public databases. Maximum annotation was resulted from UniPROT database while COG has annotated least number of unigenes. To further analyse the BLAST results, the E-value and similarity distribution were calculated. Statistical analysis showed that 57% of mapped sequences had significant homology (<1.0E-49) and the remaining unigenes showed homology with E-value < 1E-150 (Supplementary Figure S2A). It was observed that about 18% of annotated transcripts had a similarity higher than 80% while 47% unigenes showed similarity between 60–80% (Supplementary Figure S2B). The total 65% of transcripts showing higher identity along with high quality e-value supported reliability of de novo assembly performed in the study. The assembled unigenes showed maximum hits to sequences of Arabidopsis (49%). The next closest plant was Thellungiella with 37% resemblance followed by 10% with Oryza (Supplementary Figure S2C). Annotated unigenes of C. procera were functionally categorized based on Gene Ontology (GO) classification system and each unigene was allotted at least one GO term. GO annotations were further classified into three major functional ontologies as biological process, cellular component and molecular functions. Top 10 categories of each class are represented in Fig. 2. Within the Biological process category, 2490 GO terms were assigned to 31,323 unigenes. “Proteolysis” (486 unigenes), “transcription” (468 unigenes) and “regulation of transcription” (394 unigenes) were among the top three represented groups respectively. Total 21878 unigenes categorized to Molecular function category with 1513 GO terms, top three abundant groups as “ATP binding” (2006 unigenes). “Zinc ion Binding” (1019 unigenes) and “DNA binding” (965 unigenes). Cellular components category included a total of 294 GO terms with 16358 unigenes. Top three categories in Cellular components were “nuclear”, “integral to membrane” and “plasma membrane” with 2946, 1746 and 1400 unigenes respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Gene ontology analysis of C. procera unigenes.

The results are summarized in three main categories as Biological process, Molecular function and Cellular component. Slices show top ten most represented GO terms from each domain.

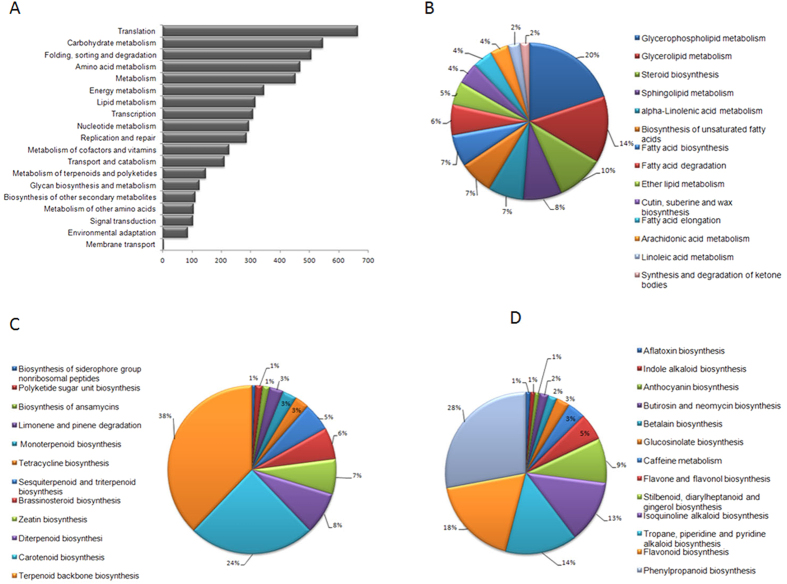

Metabolic pathway analysis by Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes pathway database helped us in identifying unigenes involved in metabolic pathways and their biological functions53. All the unigenes were analysed in the KEGG pathway database with an E-value cutoff of less than 10−5. A total of 5324 (12.6%) annotated unigenes showed significant matches in KEGG database and were categorized in 19 pathway functions involving 133 KEGG pathways of plant metabolism (Fig. 3A). Highest numbers of unigenes were clustered into “Translation pathway (665 unigenes)” followed by “Carbohydrate metabolism (546 unigenes)”, “Folding, sorting and degradation (506 unigenes)”, “Amino acid metabolism (468 unigenes)” and others. To further explore the function of the unigenes in relation to secondary metabolism “Metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides (148 unigenes)”, “Biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites (111 unigenes)” and “Lipid metabolism (316 unigenes)”, were further assigned to 14, 13, 12 subcategories respectively. Terpenoids backbone biosynthesis (56), Carotenoid biosynthesis (36), and Diterpenoid biosynthesis (12) were the top categories of “Metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides” (Fig. 3B). “Biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites” had Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (31), Flavonoid biosynthesis (20) and Tropane, piperidine and pyridine alkaloid biosynthesis (16) as the top categories (Fig. 3C). Top three representatives of “Lipid metabolism” included Glycerophospholipid metabolism (63), Glycerolipid metabolism (43) and Steroid biosynthesis (31) (Fig. 3D). Unigenes involved in terpenoids, steroid and other secondary metabolite biosynthesis were well represented in the data. This information was used for the identification of genes involved in cardiac glycoside biosynthesis in C. procera.

Figure 3. KEGG analysis of C. procera unigenes.

(A) Percentage of C. procera unigenes in 19 sub-categories of metabolic pathway category. (B) 13 sub-sub categories of metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides. (C) 12 sub-sub categories of biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites. (D) 14 sub-sub category of Lipid metabolism.

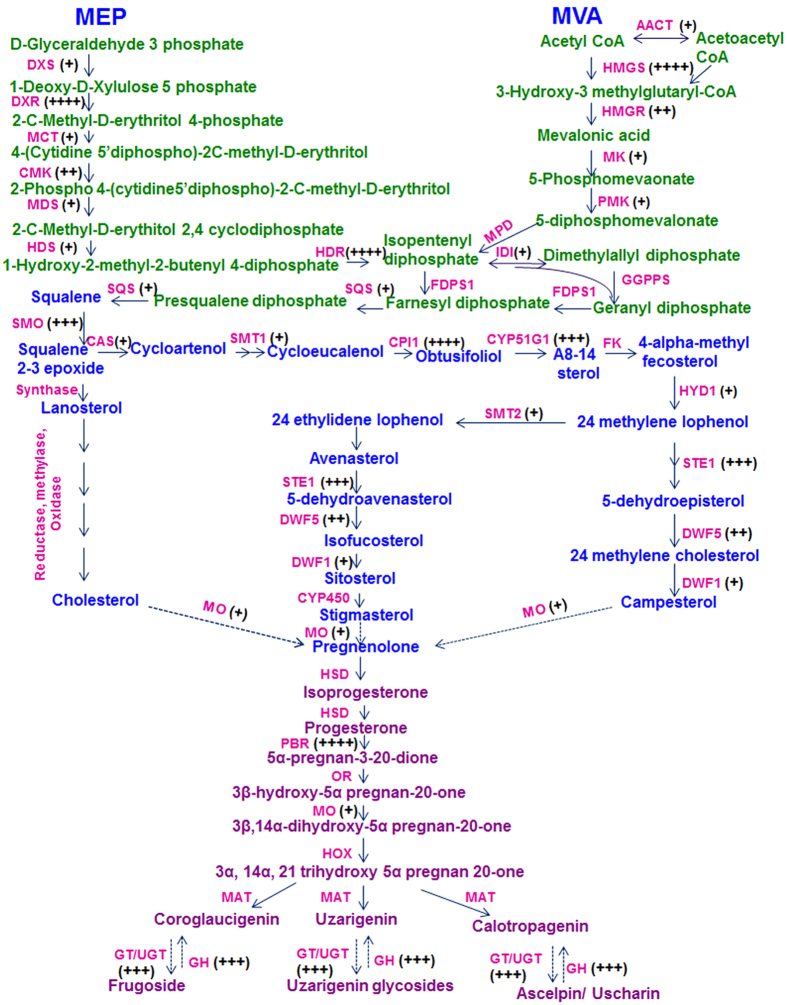

Identification of transcripts involved in cardiac glycoside biosynthesis

Previous studies suggest that CGs are synthesized in plants via intermediate Pregnanes54. Formation of this intermediate molecule is supposed to be derived from mevalonic acid via triterpenoid and phytosterols intermediate. Predominance of either terpenoid pathway precursors (MVA or MEP pathway) in synthesis of cardenolide intermediate is not clear yet55,56. Total 47 unigenes related to terpenoid backbone biosynthesis were annotated from the transcriptome data. Together these unigenes represent 16 gene families of terpenoid backbone biosynthesis57. Identification of transcripts related to enzymes of both terpenoid sub-pathways suggest that precursor from both pathways are utilized in synthesis of various intermediates in C. procera (Fig. 4). Formation of Squalene embraces the beginning of steroid backbone which through formation of several intermediates ends up in Pregneolone58. These steps are catalysed by 13 steroid biosynthesis-associated gene families, mainly including reductase, oxidases and methylases, out of all 12 homologues were identified from our transcriptome data. These 12 gene families were represented by 53 unigenes in the datasets (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Putative cardenolide biosynthetic in C. procera.

The pathway has been divided into three subgroups as terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, steroid biosynthesis and cardenolide biosynthesis. The enzymes with corresponding unigenes are mapped. Fold induction is represented by + sign; 0–2(+), 2–4(++), 4–10(+++), >10(++++) Full names of genes are mentioned in Supplementary Table 4.

Formation of Pregnelone is the branch point for cardiac glycoside backbone biosynthesis. Total 11 gene families are assumed to be involved in conversion of Pregenolone to cardiac glycoside out of which, only five gene families were identified in the study. Conversion of Pregnenolone to Progesterone is catalysed by 3β-HSD enzyme59. In our study, 15 transcripts were showing homology to 3β-HSD, but all were partial sequences none coding for full ORF. Once the progesterone is synthesized it is immediately reduced to one of intermediates Pregnane-dione with the enzyme 5βPOR60,61. Full length gene coding for 5βPOR was annotated from two transcripts. Four transcripts showing similarities with glucohydrolase enzymes were identified which may have cardenolide 16-O-glucohydrolase enzymes like activity. Till date only one gene, i.e. 5βPOR, progesterone 5β-reductase have been characterised from this plant and our transcript annotating to 5βPOR showed 100% homology to this gene sequence62.

Cytochrome P450 monoxygenase are mediators of oxidation reaction involved in the synthesis of large variety of secondary metabolites in plants63. Total 90 transcripts were annotated to different monoxygenase which may be involved in various steps of cardiac glycosides biosynthesis. Similarly 125 transcripts were annotated to GT/UGT (glycosyl transferase/glucuronosyl transferase/UDP-glycosyl transferase/glucuronosyl transferase) which may be involved in the last steps of cardiac glycosides biosynthesis. They catalyse glycosylation of genin units to glycosides. Identification of the specific GT/UGT, Mono-oxygenase and Glucohydrolase involved in biosynthesis and inter-conversion of genin and glycoside will impart a new direction towards the study of the cardiac glycoside biosynthetic pathway and its related genes. (Fig. 4)

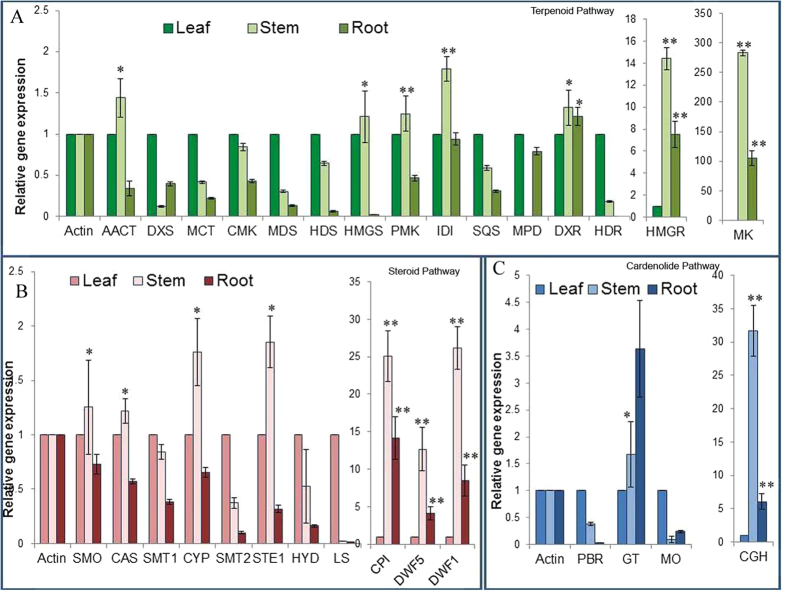

Tissue specific expression profiling of transcripts involved in cardiac glycoside biosynthesis

To lay down the biosynthetic pathway and correlation of the CGs accumulation with the putative transcripts which were identified in the study, tissue specific expression of thirty transcripts representing different gene families involved in CG biosynthesis were studied (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

(A) Tissue specific expression of genes involved in terpenoid backbone biosynthesis by qRT-PCR. (B) Tissue specific expression of genes involved in steroid backbone biosynthesis by qRT-PCR. (C) Tissue specific expression of genes involved in cardenolide biosynthesis by qRT-PCR. The stem and root group compared with leaf group. The data represents three independent biological and experimental repeats with standard deviations. Asterisk *(P < 0.05) and **(P < 0.001) indicate significant differences as determined by Student’s t test. Full names of genes are mentioned in Supplementary Table 4.

Almost all the transcripts were accumulated in the aerial part (leaf and stem) of the seedling. Most transcripts of terpenoidal pathway were showing accumulation in aerial parts (leaf and stem). Out of 15 putative genes studied, 07 were significantly up-regulated in the stem when compared with the leaf tissue. Maximum accumulation was observed for Mevalonate Kinase (MK) and hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR) in stem (Fig. 5A). Similarly majority of transcripts, i.e. 07 out of 11, coding genes for steroid backbone were significantly up-regulated in the stem when compared with leaf and root tissue. Maximum accumulation was observed for transcripts of Cyclopropyl isomerase (CPI), Delta 24-sterol reductase (DWF1) and Sterol delta 7 reductase (DWF5) (Fig. 5B). Among five studied transcripts of cardiac glycosides pathway studied, maximum accumulation of about 31.7 fold in stem was observed for Cardenolide glucohydrolase (CGH) (Fig. 5C).

Tissue specific expression of transcripts involved in CG biosynthesis was in accordance with the CG accumulation in different tissues where most of cardiac glycosides were observed in the aerial parts of the seedlings particularly stem tissue.

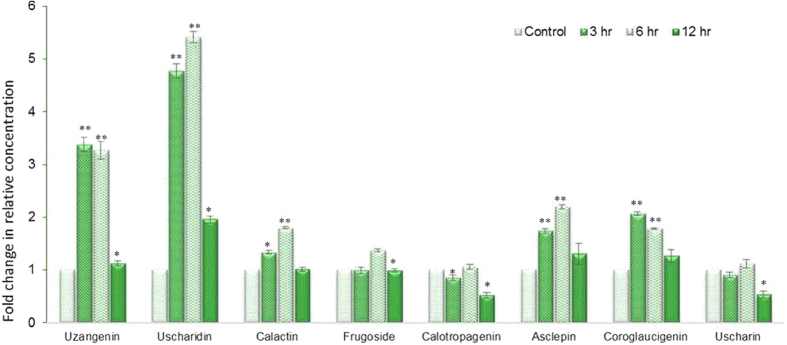

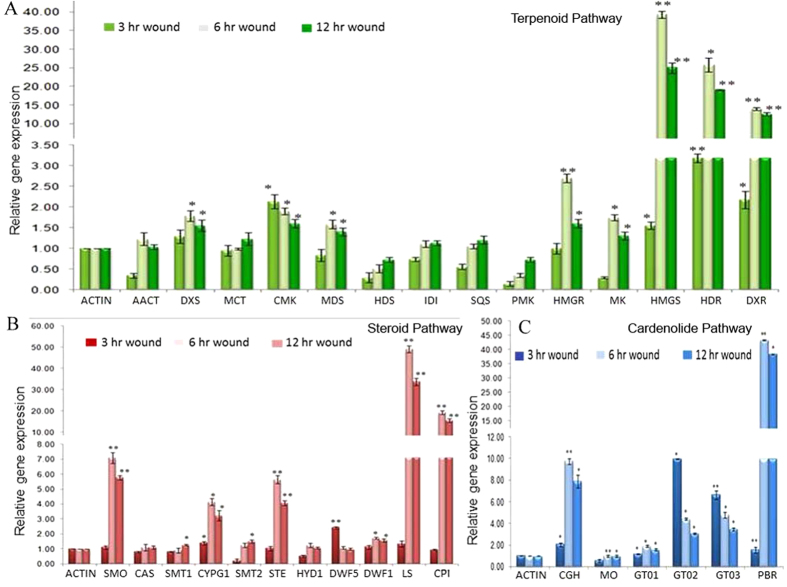

Effect of wound treatment on cardiac glycoside accumulation and their related biosynthetic genes

Many secondary metabolites found in plants have a role in defence against herbivores, pest and pathogens64. Several classes of these secondary products are induced by infection, wounding or herbivore65. To study the effect of wounding on accumulation of cardiac glycosides we subjected 3 month whole seedlings to mechanical wounding for 3, 6 and 12 hours and estimated cardiac glycosides using LC/MS-MS. Five out of seven metabolites showed significant accumulation in response to wound stress. Genin units were accumulated maximally in response to 3 hr of wounding and maintained higher concentration till 6 hr and reverted to their basal level within 12 hours of stress (Fig. 6). Uzarigenin showed more than 3-fold induction in 3 and 6 hr of wounding, two-fold accumulation in Coroglaucigenin concentrations were observed in response to 3 hr of wounding. Level of Calotropagenin remained unaltered after wounding (Fig. 6). Cardiac glycosides showed different accumulation patterns as their level increased up to 6 hr of wounding and then returned to the basal level. Highest accumulation was observed for Uscharidin which was up to 4.8 and 5.4 folds higher in comparison to control after 3 and 6 hr of wounding respectively (Fig. 6). Similarly, Calactin and Asclepin also showed 1.8 and 2.2-fold accumulation after 6 hr of wounding when compared with control whereas a significant increase of 1.4 fold was observed in Frugoside concentration after 6 hr of wounding (Fig. 6). There was no increase in level of Uscharin concentration up to 6 hr of wounding and after 12 hr of wound stress the level of Uscharin decreased significantly as compare to control (Fig. 6). To correlate the accumulation pattern of cardiac glycosides with 32-putative genes of biosynthetic pathway, a relative expression analysis was done after 3, 6, 12 hr of wound treatment. Like metabolites almost three-fourth of putative genes were also significantly accumulated in response to wound stress. Among 15 transcripts of terpenoid pathway, 8 showed induction in the range of 1.5–40 folds. Majority of them showed gradual increase in the transcript level at 3 hr of wounding which reached maximum at 6 hr followed by decrease in the accumulation of transcripts after 12 hr of wounding. Three transcripts viz hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA (HMGS), 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase (HDR) and 1-Deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR) showed high accumulation of 40, 25 and 15 folds respectively after 6 hr of wound stress (Fig. 7A). There was no significant effect of wounding on transcripts of Acetyl-Co-AC-acetyltransferse (AACT), 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase (MCT), 4-hydroxy-3-methyl-2-en-1-yldiphophate synthase (HDS), Isopentenyl-diphosphate delta-isomerase (IDI), Squalene synthase (SQS) and Phosphomevalonate Kinase (PMK).

Figure 6. Accumulation of CGs and genin units after 3, 6, 12 hr of wounding in C. procera whole plant measured with LC-MS/MS.

Each value is the mean of three replicates, and error bars indicate SDs. Asterisk *(P < 0.05) and **(P < 0.001) indicate significant differences as determined by Student’s t test.

Figure 7. Relative expression level of genes involved in cardenolide biosynthesis after wound treatment.

(A) Effect of wound on expression of genes involved in terpenoid backbone biosynthesis by qRT-PCR. (B) Effect of wound on expression of genes involved in steroid backbone biosynthesis by qRT-PCR. (C) Effect of wound on expression of genes involved in cardenolide biosynthesis by qRT-PCR. Actin was used as internal reference gene and relative abundance of each gene was compared after 3, 6 and 12 hr of wounding. The data represents three independent biological and experimental repeats with standard deviations. *(P < 0.05) and **(P < 0.001) indicate significant difference in gene expression (control vs wound). Full names of genes are mentioned in Supplementary Table 4.

Similarly, transcripts identified in steroid biosynthesis were also found to be wound responsive except for SMT1, SMT2, CAS and HYD1. All induced transcripts uniformly showed highest accumulation at 6 hr of wounding except for Sterol reductase (DWF5). Lupeol synthase (LS) showed maximum accumulation of 49-fold followed by 19-fold induction of CPI after 6 hr wounding. Squalene monoxygenase (SMO), Sterol desaturatses (STE1), CYP51G1 and Sterol reductase (DWF1) were also significantly up-regulated in the range of 1.7–7 folds after 6 hr of wound stress (Fig. 7B). Among the genes of the cardenolide pathway most of the transcripts were significantly induced upon wound treatment. Highest accumulation of >43-fold was observed for Progesterone 5β-reductase (5βPOR), a key enzyme of CG biosynthesis followed by >9-fold induction of Cardenolide glucohydrolase (CGH) another important enzyme of the pathway (Fig. 7C). Last steps of the cardiac glycosides biosynthesis include glycosylation of respective genin units to their glycoside which are catalysed by Glycosyltransferases (GT). All the three GT transcripts studied were wound responsive, but the maximum accumulation of >10 fold was observed for GT02 in response to 3 hr of wounding, There was no alternation in the expression of selected mono-oxygenase transcript in response to wounding.

Discussion

With establishment of economic importance of C. procera, in the last five years this plant has been explored for the identification of genes involved in stress biology66,67, genes related to fibre development68 and profiling of Cysteine Protease from this plant69 through de novo sequencing. Despite of immense medicinal importance of Cardiac glycosides of this plant, putative genes involved in biosynthesis of CG have not been studied well. De novo transcriptome sequencing proves a promising tool for gene identification, especially for those plants whose genome sequences are unavailable70,71. Using similar approach putative biosynthetic pathways have been identified from important medicinal plants72,73. One such approach was utilized in case of Digitalis purpurea for identification and elucidation of putative CG biosynthetic pathway74.

Stage specific CGs accumulation suggested that young plants (3 month old) are better candidate for transcriptome analysis as they accumulate more CGs in comparison to mature plants. These findings were in agreement with pervious finding for CG accumulation in different plant75. Secondary metabolites are synthesized as per specific requirements of plants in response to the nature, the probable cause of more CGs biosynthesis in young plants (3 month old) may be due to defence against wounding or herbivore as young plants are more prone to it76. From tissue specific metabolic profiling it was concluded that although, maximum accumulation was in the stem, but the considerable amount of CGs was detected in the other tissues also. So, three month whole seedlings were selected for the transcriptome sequencing to elucidate the cardiac glycoside biosynthetic pathway.

De novo assembly of C. procera resulted in 44074 unigenes with an average length of 1785 base pairs. More than 66% assembled sequenced were annotated, out of which 75% of the annotated sequences showed high sequence similarities (>60%) with the known protein from different databases further validating the sequence assembly. The annotation and similarity percentage was in accordance with the previous findings77,78. A total of 4297 GO terms were categorised under ‘biological processes’, ‘molecular function’ and ‘cellular component’. The rest of the sequences probably remained unannotated due to the un-translated regions/non coding RNA or short sequences not having any conserved protein domain, as well assembly mistakes cannot be ruled out. Mapping of unigenes onto the KEGG pathways helped in the identification of a large number of unigenes involved in biosynthesis of various metabolites in C. procera.

Cardiac glycosides are synthesized in plants via Pregnanes, which utilise a number of intermediate from terpenoidal and steroidal pathways79. About 100 unigenes, representing 29 gene families from both these sub-pathways were identified from the data set. Pregnane undergoes various modifications to yield final products as cardiac glycosides which involve 11 gene families. 236 unigenes, representing transcripts of Δ5-3, β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases/3-KSI, 5-3-ketosteroid isomerase (in total as 3β-HSD), progesterone 5β-reductases (5β-POR), mono-oxygenases, cardenolide 16′-O glucohydrolases (CGH), and glycosyltransferases (GT) were identified. 5β-POR is the only enzyme characterized from C.procera. It catalyse the transformation of progesterone to 5β-pregnane-3, 20-dione.

Fifth most abundant transcript of the data set belongs to Mono-oxygenase with 90 transcripts representing 40 loci; shedding light on the active steroid biosynthesis within the plant. Glycosylation is the last step in cardiac glycosides biosynthesis which is catalysed by a super large gene family in plants UGTs80. These are key modifying enzymes in the CG biosynthesis and are largely responsible for its diversity within plant Calotropis. Large numbers of GT/UGTs are required for the synthesis of diverse type of CGs within plant as represented by the large number of unigenes with the same function81. Also 04 loci of Cardenolide glucohydrolases enzymes involved in hydrolysis of primary CGs have been identified from the data set. The representative transcripts associated with biosynthesis were accumulated more in stem tissues followed by leaf and roots in 3 month old plants, explaining that probably in young plants, green stem and leaves are site of CG biosynthesis and its accumulation. Our results showed parallel accumulation of cardiac glycosides and transcripts related to CG biosynthesis in a tissue specific manner.

Cardiac glycosides have been evolved as a means of the general defence system82 and are widely distributed among different genera of Apocynaceae83,84,85. Various elicitations and mechanical wounding (mimicking herbivory) have been shown to enhance these chemical defence of plants. These finding paved the way to study the effect of wounding on accumulation of CGs and we observed that CGs get accumulated in response to wound stress. Similar induction in level of CGs were recorded after mechanical damage over a short period of time in Asclepias86. Enhanced cardenolide accumulation after application of mechanical wounding has also been reported in Calotropis gigantea hairy root culture87. In our study a similar induction in level of cardiac glycosides was observed after wound treatment. Genin units which are storage forms of cardiac glycosides showed early response to wounding. Wound treatment might be inducing their secretion from vacuoles so that they may be readily available in free form to get converted into their respective glycosides. Respective glycosides like Uscharidin, Asclepin, Calactin were also wound responsive but a late induction pattern (at 6 hrs) was observed for them. Wound may also be stimulating translocation of already synthesised cardiac glycosides from their site of synthesis to site of action which explains their late induction at 6 hrs.

It has been observed that terpenoid88 and cardiac glycosides gets accumulated on wounding stress89, therefore, identified transcript were studied for their accumulation in response to wound stress and it was observed that most of the transcript were wound responsive and were accumulated in different patterns. HMGR and DXS are rate limiting steps of isoprenoid pathway and their transcript level increases upon wounding90, the same was observed in our study. It was observed that increased expression of 5β–POR was consistent with higher accumulation of CGs in Digitalis plant91. In our study we also observed the same co-relation between higher accumulation of CGs and 5β–POR. Early increase in transcript level of GT may be explained by the fact that upon wounding genin gets rapidly glycosylated and convert into glycosides for immediate defence response. 64 unigenes were annotated as GT and only three were studied for wound response. There exists possibility of more wound responsive GT which may be playing an active and specific role in cardiac glycosides biosynthesis. Identification of such genes will further elaborate the facts on biosynthetic pathway in Calotropis procera. Increased expression of most of the transcripts in response to wounding suggested that CGs are probably synthesized upon wounding and it may have some role in wound response or wound mediated signal transduction within plants. The present study has helped in identification of novel cardiac glycosides related transcripts involved in CG’s biosynthetic pathway. Such approach of wound treatment to induce and identify metabolic pathway genes has been used in number of plants like Catahranthus92, Nicotiana93 and Opium94. The characterization of these gene transcripts in either homologous or heterologous system will further lay down the progress towards metabolic engineering of CG’s. However, such metabolic engineering requires complete knowledge of wound response of a particular metabolite as well as associated biosynthetic genes.

Method

Plant Material and Wound treatment

Seeds of C. procera were planted and grown in pots filled with a mixture of soilrite and vermiculite (1:3, v/v) for 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. The plants were watered every alternate day. Whole plant was harvested at respective months and dried in oven for LC/MS analysis. Root, stem and leaf were also harvested at 3 month old plant. For gene expression analysis, whole seedling was washed with DEPC treated water, dried, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for further analysis. For wound treatment, 3 months old seedling was pricked with sterile needle uniformly and harvested after 3 and 6 and 12 hr respectively.

cDNA library construction for de novo Sequencing

Tissues from 10 seedlings (3 month old whole seedling) were pooled together and RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) and subsequently used to construct library with TruSeq RNA Sample preparation kit V2 (Illumina, Cat RS-122-2002) following manufactures protocol. 1 μg of total RNA by Qubit was enriched for Poly A using RNA Purification Beads. Enriched Poly-A RNA was fragmented for 4 minutes at 94 °C in the presence of divalent cations. First strand cDNA was made by Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA) using random hexamers followed by synthesis of second strand cDNA in the presence of DNA polymerase I and RNaseH. The cDNA was cleaned using Agencourt Ampure XP SPRI beads (Beckman Coulter, USA). SPRI cleaned cDNA was ligated with “Illumina Adapters” after end repair and addition of “A”- base. For the enrichment of adapter ligated fragments, library was amplified using 8 cycles of PCR. The prepared library was quantified using nanodrop. Quality validation of the library was done by running an aliquot on a High Sensitivity Bioanalyzer Chip (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA).

Sequencing and de novo assembly

Illumina HiSeq was used to generate 2x Paired end (101 bp max) raw reads. Quality control of Illumina Hi Seq paired raw reads was done using SeqQC V2.1. In-house script was used for low quality bases trimming towards 3′-end. Adapter sequences and empty reads were also trimmed before assembly of reads. de-novo assembly of Illumina HiSeq data was performed using velvet-1.2.1095 for various k-mers and it was concluded that the hash length (k-mer) 59 was better than others considering various parameters like total number of contigs generated, maximum contig length, total contig length and less number of N’s.

Using Velvet assemblies as input, transcriptome assembly was done by Oases 0.2.08 with hash length 59, under default parameters with minimum transcript length cutoff of 20 bp96. These Velvet assemblies were grouped into loci which were later used for construction of transcript isoform. Transcripts with at least 200 bases were considered for further analysis. Unigenes were further processed to remove redundant sequences. Using CD-HIT v4.5.4, clustering of unigenes was done and non-redundant unigenes were acquired97.

Sequence annotation and Functional classification

Annotation of unigenes was done using the BlastX algorithm98. Various protein databases like NCBI non-redundant protein database99, UniProt100, Pfam101 were searched for homologs. The Blast algorithm was used to identify homologous sequences with a cut-off value less than 10−5. Gene name were assigned to each sequence based on best Blast hit. GO annotation was assigned to the all the annotated unigenes using Blast2GO program102. GO terms were mainly divided into biological processes, molecular functions and cellular components. Assembled sequences were assigned (KEGG) pathways using online KAAS (KEGG Automatic Annotation Server). KEGG-orthology (KO id) was procured through bi-directional best hit method103.

Sample preparation and analysis of CGs by Liquid chromatography/ Mass spectrometry

Plant parts harvested was dried in oven at 37 °C. These samples were grinded to fine powder with the help of mortar and pestles. 500 mg of each sample was extracted with 10 ml absolute ethanol and kept on shaker for 48 hr, after which extract were filtered by Whatmann No. 1 filter paper and filter sterile through 0.25 micron filters. The LC-MS and LC-MS/MS were performed on a Waters TQD triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (USA). It was equipped with waters, H-Class Acquity UPLC system and electrospray ionization source. The UPLC column used was water BEH C-18 100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm and dual mode (±) LC-ESI-MS experiments performed after injecting 1 μl samples by the autosampler. Similarly, LC-ESI-HRMS analysis was performed on Agilent 6500 Q-Tof Mass Spectrometer (USA). It was equipped with electrospray ionization (ESI) interface using the following operation parameters: capillary voltage 3.5 kV, nebuliser 40 psi, drying gas (nitrogen) flow rate 11.0 L/min, drying gas temperature 300 °C, fragmentor 150 V, skimmer voltage 65 V. Mass spectra were recorded across the range m/z 150–1000 Th. The accurate masses of selected metabolites were observed and compared with their exact mass (theoretical mass) values manually. Analyses were performed as per our previously established method. m/z values and retention time of different compounds identified are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Identification of cardiac glycosides by their characteristic fragment ions.

| S. No. | RT | M.W. | Identified | m/z (Characteristic fragment ions of genin) | Genin unit | Sugar unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 5.34 | 404 | Calotropagenin | 387,369,351,341,333,323,305 | A | — |

| 02 | 6.78 | 536 | Frugoside | 391,373,355,339,337,325,293 | C | 146 |

| 03 | 6.89 | 390 | Coroglaucigenin | 373,355,339,337,325,293 | C | — |

| 04 | 7.85 | 532 | Calotropin | 387,369,359,351,341,333,323 | A | 146 |

| 05 | 9.04 | 374 | Uzarigenin | 357,339,321,293 | B | — |

| 06 | 9.46 | 574 | Asclepin | 387,369,351,341,333,323 | A | 188 |

| 07 | 9.47 | 530 | Uscharidin | 387,369,351,333,323 | A | 144 |

| 08 | 9.90 | 586 | Uscharin | 323,333,341,351 | A | 201 |

A = Calotropagenin, B = Uzaigenin, C = Coroglaucigenin [Structure characterization of all above cardiac glycosides were based on their mass spectrometry based evidence (molecular weights, accurate mass measurement/chemical formula, characteristic MS/MS fragmentation of genin unit) and literature support].

Quantitative Real-Time PCR analysis

For qRT-PCR RNA from 3- month old seedlings isolated using Trizol reagent and quantified using Nanodrop. 5 μg total RNA from the samples was taken for making single-stranded cDNA using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA). cDNA was diluted 10 times with de-ionised water. Primers used in the study are given in supplementary table 3. The reaction was performed on 7500 FAST Real Time PCR system using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara). Melting curve analysis was done to verify the reaction specificity. Following thermal cycling parameters were used: initial denaturation (95 °C for 5 min); 40 amplification cycles (95 °C for 20 sec, 58 °C for 30 sec, 72 °C for 20 sec). Internal reference gene Actin was used to normalise expression levels of unigenes. Relative expression level of unigenes in tissues was calculated using the delta-delta Ct (2−ΔΔCt) method104. All the experiments were expressed as mean ± SD after normalization.

Conclusion

With critical observation and the best of our knowledge, we found that 3 months old seedlings had maximum CGs accumulation which was validated through Cardiac Glycoside profiling at different developmental stages of C. procera. For the first time Illumina HiSeq 2x Paired end method was used for the transcriptome assembly and characterization of C. procera (3 months old seedling was used). This work represents the de novo transcriptome sequencing analysis of tissues of 10 whole plant seedling RNAs. Total 44074 unigenes were generated, and 5324 unigenes were matched with KEGG database, which are involved in 133 different pathways of plant metabolism. Out of 5324 unigenes, 336 unigenes were classified in 33 gene families, which were involved in CGs biosynthesis. There are a broad class of enzymes such as Mono-oxygenases, Oxidoreductases, Transferases, Hydrolases etc. Through GO annotation and expression profiling validation, we were succeeded in sorting of the unigenes which may lead to CGs biosynthesis. Additionally, this study generated raw data which can be used for the advancement in the field of molecular markers (through Expressed sequence tag simple sequence repeats “EST-SSRs”). MIcroSAtellite identification (MISA) was the tool which can be used to identify EST-SSR repeats. This study sets a platform of valuable gene sequences for the de novo gene discoveries and further exploration of the CGs pathway of C. procera.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Pandey, A. et al. Transcriptome and Metabolite analysis reveal candidate genes of the cardiac glycoside biosynthetic pathway from Calotropis procera. Sci. Rep. 6, 34464; doi: 10.1038/srep34464 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge Director CSIR-CDRI for providing the necessary facilities. Authors acknowledge CSIR network project BSC0106 for providing financial assistance and SAIF, CSIR-CDRI for LC-MS/MS analysis and Genotypic Technology Pvt. Ltd. for providing SeqQC V2.1 tool for quality check of reads. VT acknowledges GAP0180 for funding. AP, VS and TP are grateful to UGC for providing fellowships. The manuscript represents CSIR-CDRI communication no. 9328.

Footnotes

Author Contributions A.P. performed experiments, bioinformatics analysis and drafted manuscript. V.S., T.P. and P.S. assisted in data analysis. D.K.M. authenticated plant and contributed in finalizing manuscript. S.K. LC-MS/MS data acquisition and analysis. V.T. designed the experiments, coordinated the study and finalizes the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscripts.

References

- Rahman M. A. & Wilcock C. C. A taxonomic revision of Calotropis (Asclepiadaceae). Nordic J. Bot. 1, 301–308 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Mueen A. K. K., Rana A. C. & Dixit V. K. Calotropis species (Ascelpediaceae)-a comprehensive review. Pharmacog Mag. 1, 48–52 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. K., Raghubanshi A. S. & Singh J. S. Medical ethnobotany of the tribals of Sonaghati of Sonbhadra district, Uttar Pradesh, India. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 81, 31–41 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti S., Wahane V. D. & Kumar V. L. Protective effect of Calotropis procera latex extracts on experimentally induced gastric ulcers in rat. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 127, 440–444 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V. L. & Arya S. Medicinal uses and pharmacological properties of Calotropis procera. Vol. 11. Recent Progress in Medicinal Plants. Texas, Unites State, Stadium Press (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P. & Sharma J. D. In-vitro schizonticidal screening of Calotropis procera. Fitoterapia. 71, 77–79 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A., Katewa S. S., Sharma S. K., Galav P. & Jain V. Snakelore and indigenous snakebite remedies practised by some tribals of Rajasthan. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge. 10(2), 258–268 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Setty S. R. et al. Hepatoprotective activity of Calotropis procera flowers against paracetamol-induced hepatic injury in rats. Fitoterapia. 78, 451–454 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A. & Chaudhuri A. K. Nag. Preliminary studies on the anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of Calotropis procera root extract. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 30(3), 319–324 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priya S. & Jennifer S. Antipyretic activity of methanolic extract of leaves of Calotropis procera. 5(2) (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Mascolo N., Sharma R., Jain S. C. & Capasso F. Ethnopharmacology of Calotropis procera flowers. J. Ethnopharmacol. 22, 211–221 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi M. A., Qureshi N. M., Arshad R. & Begum R. A study on the anti-sperm activity in extracts from different parts of C. procera. Pak. J. Zool. 23, 161–166 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Kishore N., Chopra A. K. & Khan O. Antimicrobial properties of C. procera Ait. in different seasons: a study in vitro. Biol. Mem. 23, 53–57 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Kuta F. A. Anti-fungal effect of C. procera stems bark on Epidermophyton flocosum and Trichphyton gypseum. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 7, 2116–2118 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Newman R. A., Yang P., Pawlus A. D. & Block K. I. Cardiac glycosides as novel cancer therapeutic agents. Mol Interv. 8, 36–49 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choedon T., Mathan G., Arya S., Kumar V. L. & Kumar V. Anticancer and cytotoxic properties of the latex of Calotropis procera in a transgenic mouse model of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 12(16), 2517–2522 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaquebeke E. V. et al. Identification of a novel cardenolide (2″-oxovoruscharin) from Calotropis procera and the hemi-synthesis of novel derivatives displaying potent in vitro anti-tumor activities and high in vivo tolerance: structure activity relationship analyses. J Med Chem. 48, 849–885 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur R., Gupta, , Mathur S. R. & Velpandian T. Anti-tumor studies with extracts of Calotropis procera (Ait.) R. Br. root employing Hep2 cells and their possible mechanism of action. Indian J Exp Biol. 47, 343–348 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira J. S. et al. In vitro cytotoxicity against different human cancer cell lines of laticifer proteins of Calotropis procera (Ait.) R. Br. Toxicol in vitro. 21, 1563–1573 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiber J. N., Nelson C. J. & Lee S. M. Cardenolides in latex and leaves of seven Asclepias species and Calotropis procera. Phytochemistry 21, 2343–2348 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Khan Q. & Malik A. A steroid from Calotropis procera. Phytochemistry 28, 2859–2861 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Shaker K. H., Morsy N., Zinecker H., Imhoff J. F. & Schneider B. Secondary metabolites from Calotropis procera (Aiton). Phytochem Lett. 3, 212–216 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Bhutani K. K., Gupta D. K. & Kapil R. S. Occurrence of D/E trans stereochemistry isomeric to ursane (cis) series in a new pentacyclic triterpene from Calotropis procera. Tetrahedron Lett. 33, 7593–7596 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Nenaah G. Antimicrobial activity of Calotropis procera Ait. (Asclepiadaceae) and isolation of four flavonoid glycosides as the active constituents. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 29(7), 1255–1262 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossa J. S. et al. Pharmacological studies on aerial part of Calotropis procera. American journal medicine of Chinese medicine. XIX(3–4), 223–231 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse G. & Lettenbauer G. A. 2nd sulfur-containing compound from the milky-juice of Calotropis procera. Angew Chem. 69, 392 (1957). [Google Scholar]

- Hassal K. & Reyle K. Cardenolides. Part III. The constitution of calotropagenin. J Chem Soc. 85–89 (1959). [Google Scholar]

- Hesse G. & Ludwing G. African arrow poisons XIV. Voruscharine, a second sulfur-containing heart poison from Calotropis procera L. Justus Lieb. Ann Chem. 632, 158–171 (1960). [Google Scholar]

- Elgamal M. H. A. et al. Complete 1H and 13C signal assignments of 5α-cardenolides isolated from Calotropis procera R. Br. J. Mol. Struct. 477, 201–208 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz A. A., Allen J. C. & Harigaya S. Possible involvement of cardiac Na/K-adenosine triphosphatase in the mechanism of action of cardiac glycosides. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 168, 31–41 (1969). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. W. The fundamental mechanism of inotropic action of Digitalis. Therapie. 44, 431–435 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen P. L., Hakansson K. O. & Karlish S. J. Structure and mechanism of Na, K-ATPase: functional sites and their interactions. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 65, 817–849 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R. et al. Therapeutic Potential of Calotropis procera: A giant milkweed. IOSR Journal of Pharmacy and Biological Sciences. 4, 42–57 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Prassas I. & Diamandis E. P. Novel therapeutic applications of cardiac glycosides. Nature Rev. Drug Discov. 7, 926–935 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki H., Nagase H. & Urakawa N. Sugar moiety of cardiac glycosides is essential for the inhibitory action on the palytoxin-induced K+ release from red blood cells. FEBS Lett . 173(1), 196–19 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreis W., Hensel A. & Stuhlemmer U. Cardenolide biosynthesis in foxglove. Planta Med. 64, 491–499 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Kreis W. & Müller-Uri F. Biochemistry of sterols, cardiac glycosides, brassinosteroids, phytoecdysteroids, and steroid saponins. Biochemistry of Plant Secondary Metabolism. 40, 304–363 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Ramstad E. & Beal J. L. Mevalonic acid as a precursor in the biogenesis of digitoxigenin. J Pharm Pharmacol 12, 552–556 (1960). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros E. G. & Leete E. Biosynthesis of plant steroids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 87, 3479–3484 (1965). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmbold H., Voelter W. & Reinhard E. Sterols in cell cultures of Digitalis lanata. Planta Med. 33, 185–187 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- Milek F., Reinhard E. & Kreis W. Influence of precursors and inhibitors of the sterol pathway on sterol and cardenolide metabolism in Digitalis lanata Ehrh. Plant Physiol Biochem. 35, 111–121 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M., Padua R. M., Herl V., Müller-Uri F. & Kreis W. Expression of 3β‐HSD and P5βR, Genes Respectively Coding for Δ5-3β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase and Progesterone 5β‐Reductase, in Leaves and Cell Cultures of Digitalis lanata EHRH. Planta Med 76(9), 923–927 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner D. E. & Seitz H. U. A stereospecific enzyme of the putative biosynthetic pathway of cardenolides. Characterization of progesterone 5β-reductase from leaves of Digitalis purpurea L. FEBS Lett. 271, 239–242 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aberhart D. J., Lloyd-Jones J. G. & Caspi E. Biosynthesis of cardenolides in Digitalis lanata. Phytochemistry. 12, 1065–1071 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- Deluca M. E., Seldes A. M. & Gros E. G. The 14b –hydroxylation in the biosynthesis of cardenolides in Digitalis purpurea - The role of 3b -hydroxy-5b -pregn-8(14)-en- 20-one. Z Naturforsch. 42c, 77–78 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Maier M. S., Seldes A. M. & Gros E. G. Biosynthesis of the butenolide ring of cardenolides in Digitalis purpurea. Phytochemistry. 25, 1327–1329 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Haussmann W., Kreis W., Stuhlemmer U. & Reinhard E. Effects of various pregnanes and two 23-nor-5-cholenic acid on cardenolide accumulation in cell and organ culture of Digitalis lanata. Planta Medica. 63, 446–453 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deluca M. E., Seldes A. M. & Gros E. G. Biosynthesis of digitoxin in Digitalis purpurea. Phytochemistry. 28, 109–111 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Schebitz P., Hensel N. A., Müller-Uri F. & Kreis W. Norcholanic acids as substrates for recombinant 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and progesterone 5β-reductase, enzymes of the 5β-cardenolide biosynthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 51, 367–370 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Heasley B. Chemical synthesis of the cardiotonic steroid glycosides and related natural products. Chemistry. 18, 3092–3120 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi P. K., Awasthi S., Kanojiya S., Tripathi V. & Mishra D. K. Callus culture and in vitro biosynthesis of cardiac glycosides from Calotropis gigantea (L.) Ait. In Vitro Cell DevBiol-Plant. 49(4), 455–460 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Kanojiya S. & Madhusudanan K. P. Rapid identification of calotropagenin glycosides using high-performance liquid chromatography electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometry. Phytochem Anal. 23, 117–125 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya Y., Itoh M., Okuda S., Yoshizawa A. & Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W182–W185 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuhlemmer U. & Kreis W. Cardenolide formation and activity of pregnane-modifying enzymes in cell suspension culture, shoot cultures and leaves of Digitalis lanata. Plant Physiol Biochem. 34, 85–91 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Faust T., Theurer C., Eger K. & Kreis W. Studies on cardiac glycosides. Fucosyltransferase activity in leaves of Digitalis lanata. Planta Med. 58, 672 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Uri F. & Kreis W. Recent advances in cardenolide research. Journal of Academy of sciences of Moldova life science. 2(311), 45–52 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey D. J. & Croteau R. Terpenoid metabolism. Plant Cell. 7(7), 1015–1026 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste P. Sterol metabolism. Vol 1 (eds. Somerville C. R., Meyerowitz E. M.) The Arabidopsis Book American Society of Plant Biologists, Rockville, MD (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herl V., Frankenstein J., Meitinger N., Müller-Uri F. & Kreis W. 2007. Δ5-3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β HSD) from Digitalis lanata. Heterologous expression and characterisation of the recombinant enzyme. PlantaMed. 73, 704–710 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herl V., Fischer G., Müller-Uri F. & Kreis W. Molecular cloning and heterologous expression of progesterone 5β-reductase (P5βR) from Digitalis lanata EHRH. Phytochem. 67, 225–223 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herl V., Fischer G., Bötsch R., Müller-Uri F. & Kreis W. Molecular cloning and epression of progesterone 5β-reductase (P5βR) from Isoplexis canariensis. Planta Med. 72, 1163–1165 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer P. et al. Highly conserved progesterone 5β-reductase genes (P5β R) from 5β-cardenolide-free and 5β-cardenolide-producingangiosperms. Phytochemistry. 71, 1495–1505 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger B. & Bak S. Plant P450s as versatile drivers for evolution of species-specific chemical diversity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 368(1612), 20120426 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett R. N. & Wallsgrove R. M. Secondary metabolites in plant defence mechanisms. New Phytologist. 127(4), 617–633 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi J. L. & Felton G. W. Foliar oxidative stress and insect herbivory: Primary compounds, secondary metabolites, and reactive oxygen species as components of induced resistance. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 21(10), 1511–1530 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan A. et al. Metabolomic response of Calotropis procera growing in the desert to changes in water availability. Plos One 9(2), e87895 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shokry A. M. et al. Detection of a Usp-like gene in Calotropis procera plant from the de novo assembled genome contigs of the high-throughput sequencing dataset. C R Biol. 337(2), 86–94 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheema H. M. N. et al. Molecular characterization and transcriptome profiling of expansin genes isolated from Calotropis procera fibres. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 13(6) (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Kwon C. W. et al. Cysteine Protease Profiles of the Medicinal Plant Calotropis procera R. Br. Revealed by de novo Transcriptome Analysis. Plos One 10(3), e0119328 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui C. et al. Transcriptome analysis of Bupleurum chinense focusing on genes involved in the biosynthesis of saikosaponins. BMC Genomics. 12, 539 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals ginsenosides biosynthetic genes, microRNAs and simple sequence repeats in Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer. BMC Genomics 14, 245 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay S., Phukan U. J., Mishra S. & Shukla R. K. De novo leaf and root transcriptome analysis identified novel genes involved in Steroidal sapogenin biosynthesis in Asparagus racemosus. BMC Genomics 15, 746 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie F. et al. De novo sequencing and a comprehensive analysis of purple sweet potato (Impomoea batatas L.) transcriptome. Planta. 236, 101–113 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B. et al. Comprehensive transcriptome analysis reveals novel genes involved in cardiac glycoside biosynthesis and mlncRNAs associated with secondary metabolism and stress response in Digitalis purpurea. BMC Genomics. 13, 15 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga F. C., Kreis W., Almeida R., Récio A. & Braga de O. Variation of cardenolides with growth in a Digitalis lanata Brazilian cultivar. Phytochemistry. 45, 473–476 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. D., Tokuhisa J. G., Reichel T. M. & Gershenzon J. Variation of glucosinolate accumulation among different organs and developmental stages of Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry. 62(3), 471–481 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annadurai R. S., Jayakumar V., Mugasimangalam R. C., Katta M. & Anand S. Next generation sequencing and de novo transcriptome analysis of Costus pictus D. Don, a non-model plant with potent anti-diabetic properties. BMC Genomics 13, 663 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanase K. et al. Transcriptome analysis of carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus L.) based on next-generation sequencing technology. BMC Genomics. 13, 292 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melero C. P., Medarde M. & San Feliciano A. A short review on cardiotonic steroids and their aminoguanidine analogues. Molecules, 5, 51–81 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Theurer C., Treumann H. J., Faust T., May U. & Kreis W. Glycosylation in cardenolide biosynthesis. Plant Cell, Tissue and organ culture. 38, 327–335 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Kreis W. & May U. Cardenolide glucosyl transferases and glucohydrolases in leaves and and cell cultures of 3 Digitalis (Scrophulariaceae) species. Journal of Plant Physiology. 136, 247–252 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Rasmann S. & Agrawal A. A. Latitudinal patterns in plant defence: evolution of cardenolides, their toxicity and induction following herbivory. Ecol. Lett. 14, 476–483 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hifnawy M. S. et al. Pergularia tomentosa cardiotonic activity of different extracts, fractions & isolated compounds. IOSR journal of pharmacy and biological sciences 9(1), 40–52 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim S. R. et al. Calotroposides H-N, new cytotoxic oxypregnane oligoglycosides from the root bark of Calotropis procera. Steroids. 96, 63–72 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamela. M. S. et al. Cardiac glycosides from Cryptostegia grandiflora. Phyto chemistry. 58, 537–542 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmann S., Agrawal A. A., Cook S. C. & Erwin A. C. Cardenolides, induced responses, and interactions between above- and belowground herbivores of milkweed (Asclepias spp.). Ecology. 90(9), 2393–2404 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Xiao J., Wang X., Yuan X. & Zhao B. Improved cardenolide production in Calotropis gigantea hairy roots using mechanical wounding and elicitation. Biotechnol Lett. 34(3), 563–569 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele C. L., Katoh S., Bohlmann J. & Croteau R. Regulation of oleoresinosis in grand fir (Abies grandis): differential transcriptional control of monoterpene, sesquiterpene, and diterpenesynthase genes in response to wounding. Plant Physiol. 116, 1497–1504 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A. A., Petschenka G., Bingham R. A., Weber M. G. & Rasmann S. Toxic cardenolides: chemical ecology and coevolution of specialized plant-herbivore interactions. New Phytol. 194, 28–45 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alex D., Bach T. J. & Chye M. L. Expression of Brassica juncea 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthase is developmentally regulated and stress-responsive. The Plant Journal. 22, 415–426 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca-Pérez L., Boluda R., Gavidia I. & Pérez-Bermúdez P. Seasonal cardenolide production and Dop5βr gene expression in natural populations of Digitalis obscura. Phytochemistry. 65, 1869–1878 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Flota F., Carrillo-Pech M., Minero-García Y. & Miranda-Ham M. L. Alkaloid metabolism in wounded Catharanthus roseus seedlings. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 42, 623–628 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin I. T. et al. Quantification, correlations and manipulations of wound-induced changes in jasmonic acid and nicotine In Nicotiana sylvestris. Planta. 201(4), 397–404 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Gurkok T., Turktas M., Parmaksiz I. & Unver T. Transcriptome Profiling of Alkaloid Biosynthesis in Elicitor Induced Opium Poppy. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 33, 673–688 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Zerbino D. R. & Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 18, 821–829 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz M. H., Zerbino D. R., Vingron M. & Birney E. Oases: robust de novo RNA-seq assembly across the dynamic range of expression levels. Bioinformatics 28, 1086–1092 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L., Niu B., Zhu Z., Wu S. & Li W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 28, 3150–3152 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. & Lipman D. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology. 215(3), 403–410 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt K. D., Tatusova T. & Maglott D. R. NCBI Reference Sequence (RefSeq): A curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 501–504 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The UniProt Consortium. The universal protein resource (UniProt). Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 190–195 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D. et al. Pfam: the protein families’ database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 222–230 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Gene Ontology Consortium. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature Genet. 25, 25–29 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M. & Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopaedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J. & Schmittgen T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2[-Delta Delta C(T)] Method Methods. 25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.