Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To improve patient safety in our NICU by decreasing the incidence of intubation-associated adverse events (AEs).

METHODS:

We sequentially implemented and tested 3 interventions: standardized checklist for intubation, premedication algorithm, and computerized provider order entry set for intubation. We compared baseline data collected over 10 months (period 1) with data collected over a 10-month intervention and sustainment period (period 2). Outcomes were the percentage of intubations containing any prospectively defined AE and intubations with bradycardia or hypoxemia. We followed process measures for each intervention. We used risk ratios (RRs) and statistical process control methods in a times series design to assess differences between the 2 periods.

RESULTS:

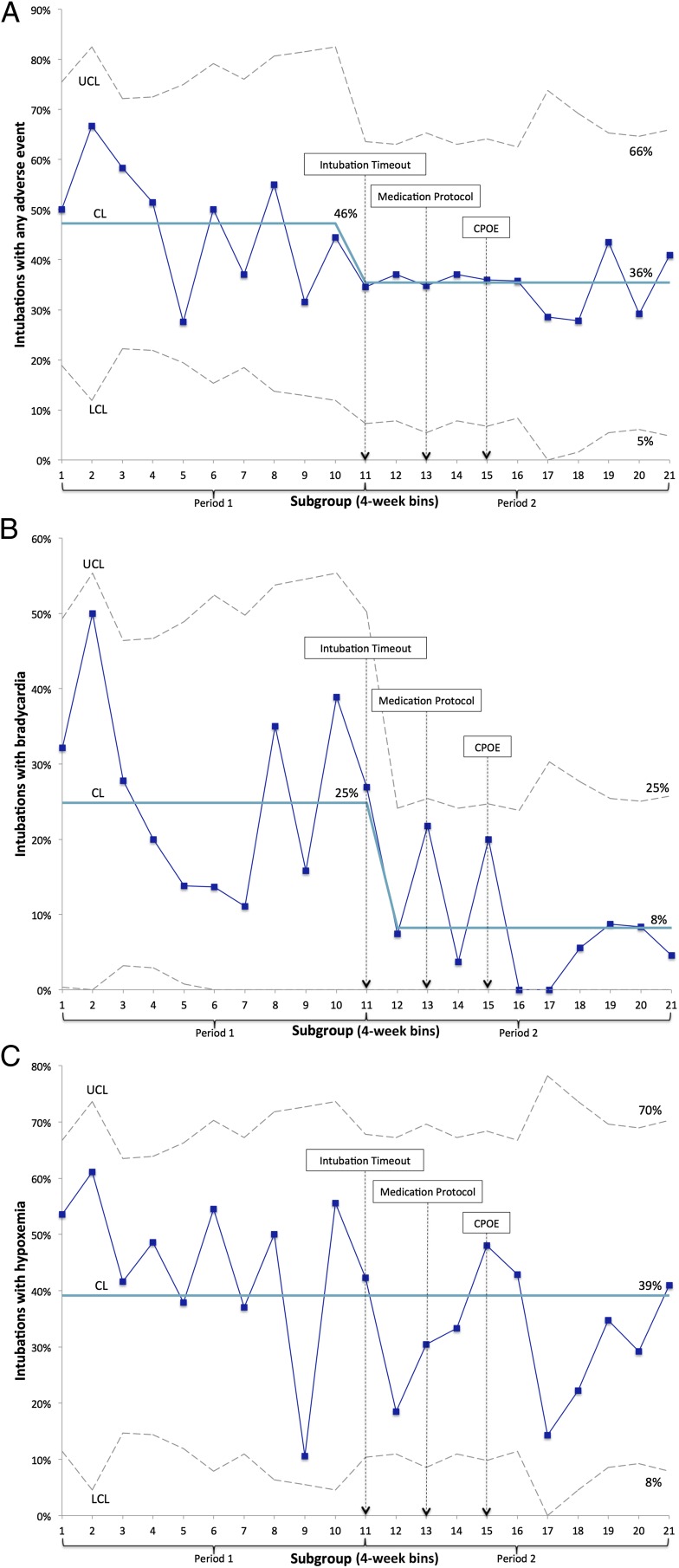

AEs occurred in 126/273 (46%) intubations during period 1 and 85/236 (36%) intubations during period 2 (RR = 0.78; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.63–0.97). Significantly fewer intubations with bradycardia (24.2% vs 9.3%, RR = 0.39; 95% CI, 0.25–0.61) and hypoxemia (44.3% vs 33.1%, RR = 0.75, 95% CI 0.6–0.93) occurred during period 2. Using statistical process control methods, we identified 2 cases of special cause variation with a sustained decrease in AEs and bradycardia after implementation of our checklist. All process measures increased reflecting sustained improvement throughout data collection.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our interventions resulted in a 10% absolute reduction in AEs that was sustained. Implementation of a standardized checklist for intubation made the greatest impact, with reductions in both AEs and bradycardia.

Infants in the NICU are one of the highest-risk groups for adverse events (AEs) in the hospital setting.1 Although high rates of medication errors and adverse drug events are well documented,2 observational studies suggest that airway-related events are also common.3–5

Reports from the National Emergency Airway Registry for Children have shown that intubation-associated AEs occur in ∼20% of intubations in children beyond the newborn period.6,7 In 2 observational studies, we and others have documented intubation-associated AEs in 22% and 39% of intubations in the NICU.3,4 Factors associated with AEs in these studies included the experience of the intubating clinician (resident, fellow, attending), use of muscle relaxants for intubation, intubation urgency (emergent versus nonemergent), and number of intubation attempts necessary to secure the airway. However, the effectiveness of interventions to decrease these AEs has not been reported.

During our observational study of endotracheal intubation in the NICU, the AE rate of 39% was higher than anticipated.4 In addition, we found substantial variability in the use of many evidence-based practices related to intubation, including premedication use and effective team communication. These findings prompted our team to develop and test quality improvement measures in an effort to improve airway safety. The aim of this quality improvement project was to improve the safety of endotracheal intubation by decreasing the incidence of intubation-associated AEs in our NICU. We hypothesized that decreasing practice variability and improving adherence to evidence-based interventions would decrease the incidence of intubation-related AEs.

Methods

Setting

We performed this project in the 100-bed, academic level IV (regional) NICU of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center. More than 1400 infants per year are admitted to the NICU from the affiliated delivery service or transferred from other hospitals. Endotracheal intubations are performed by pediatric residents, neonatal–perinatal medicine fellows, attending neonatologists, neonatal nurse practitioners or hospitalists, and subspecialty physicians. Trainees attempt intubation in approximately half of cases. Before this project, some form of premedication was used in approximately three-quarters of intubations, but no formal practice guidelines existed, and medication choices were at the discretion of the intubating clinician. The most commonly used premedication regimen was administration of a narcotic (fentanyl or morphine) and a benzodiazepine (midazolam). Vagolytics and muscle relaxants were rarely used.

Planning and Implementing the Intervention

We formed a multidisciplinary team made up of nurses, respiratory therapists, neonatal and other subspecialty physicians, and NICU leaders. By using process flow diagrams, results from root cause analyses, qualitative feedback, and baseline data, we developed a 3-stage intervention to target modifiable key drivers of AEs (Supplemental Fig 3). These key drivers were preprocedural preparation, equipment and medication availability, patient-specific situational awareness, team communication, and adequate sedation and neuromuscular blockade for intubation. Our interventions were sequentially implemented and refined according to the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Model for Improvement in a series of plan–do–study–act cycles,8 as follows:

Intervention 1: Intubation Timeout. Before our intervention, high-quality preprocedural timeouts and briefings were not routinely performed before intubation. Using principles of crew resource management,9 we developed an Intubation Timeout tool (Supplemental Fig 4) to standardize preprocedural preparation and equipment availability and improve team communication language and patient-specific situational awareness among members of the health care team. It consisted of a checklist and a prebrief script. The checklist was a do–confirm style checklist,10 where team members completed their respective assignments and then confirmed that each was done as part of the prebrief. The prebrief script consisted of a series of questions to be answered verbally at the bedside, immediately before the procedure, by the clinician performing or supervising the intubation. This prebrief took ∼30 seconds to complete. The Intubation Timeout tool was kept on a clipboard with the intubation supplies and crash carts in the NICU. This tool was designed and refined through literature review, focus groups with neonatal providers, and small trials in the NICU.

Intervention 2: Premedication for Endotracheal Intubation Algorithm. Our baseline observations identified substantial variability in premedication practices. In many cases, premedications were not used, or the regimens used were not supported by available evidence. Given these findings, we developed a premedication algorithm based on an American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical Report on premedication for nonemergency neonatal intubation.11 This algorithm (Supplemental Information 1) advocated the use of fentanyl in all infants, addition of atropine in preterm infants, use of a muscle relaxant for appropriate intubations, and limited use of midazolam. In addition, we modified our pharmacy processes to include medications on the algorithm in the bedside medication dispensing system, thus improving nursing access to these medications and subsequent workflow.

Intervention 3: Intubation Computerized Provider Order Entry (CPOE) Set. We developed a standardized order set for our CPOE system that contained both pharmacy and nursing elements. This CPOE contained the premedication algorithm and nursing reminders to use the Intubation Timeout tool, bring neonatal crash carts to the bedside before the procedure, and monitor more frequent vital signs after intubation.

Before and during each intervention period, the project team provided education about each intervention to all members of the health care team through presentations at staff meetings, e-mail reminders, and face-to-face instruction. In addition, we refined all 3 interventions through multiple iterative plan–do–study–act cycles based on provider feedback and ongoing data collection.

Measures and Study of the Intervention

We included all intubations performed in the NICU. We excluded intubations performed in the delivery room, in the operating rooms, and during transport because we were unable to reliably collect data in these locations. We used previously described data collection procedures to monitor for AEs.4 Briefly, the intubating clinician and the bedside nurse completed 2 data collection instruments during and after an intubation. These documents were used in conjunction with standardized medical record review to record outcome, process, and balancing measures. Our primary outcome measure was the percentage of intubations with ≥1 AEs. AEs were defined and classified a priori as procedural, nonsevere, or severe, and strict operational definitions were used (Supplemental Information 2). Our previous work reported only nonsevere and severe AEs.4 In this project, we also tracked a group of procedural events that did not cause identifiable harm but led to longer procedural times and more attempts at intubation (Supplemental Information 2). We tracked bradycardia (defined as heart rate <60 beats per minute for ≥5 seconds) during intubation and severe hypoxemia (defined as oxygen saturation <60%) during intubation as secondary outcomes. Process and balancing measures were defined a priori and tracked for each intervention (Supplemental Information 2). In addition, members of the project team performed direct observation of intubations and semistructured provider interviews to qualitatively understand how our interventions were being used.

We used data from our previously published observational study as our baseline.4 These data were collected over a 10-month period (period 1) from September 2013 to June 2014. Data were then collected over a 10-month period (period 2) from July 2014 to April 2015, during which we implemented our 3 interventions (4 months) and monitored for sustainment (6 months). Each individual intervention was tested and refined (through plan–do–study–act cycles) over 4 to 6 weeks. The Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board approved both the quality improvement interventions and the monitoring process with a waiver of consent for both the infants and providers.

Analysis

We used a pre–post cohort design to assess for differences between our 2 periods. Clinical variables, outcomes, process, and balancing measures were compared during period 1 and period 2 via Student’s t tests for continuous parametric data or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous nonparametric data and χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests for dichotomous data depending on the sample size. We calculated risk ratios (RRs) for our primary and secondary outcomes between the 2 periods. We excluded intubations that did not have complete AE data from the analysis.

Because our 3 interventions were sequentially implemented, we also used a time series design to evaluate our interventions.12 We tracked our primary outcomes, secondary outcomes, and process measures in real time by using statistical process control charts. We evaluated the percentage of intubations with an AE, the percentage of intubations with bradycardia, and the percentage of intubations with severe hypoxemia by using p-charts. Based on historical data, we anticipated an average of 1 intubation per day in our NICU. Using an anticipated AE rate of 30%, we used 4-week subgroup sizes for the p-charts to allow a positive lower control limit.13 We used the Western Electric rules to identify special cause variation,13 and the center line and control limits were adjusted when special cause variation was identified. Successive data points were added to the charts, with recalculation of center line and control limits with each data point. Trial limits were not used. Analyses were performed in Stata/IC 13.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX), and statistical process control charts were constructed with QI Macros for Excel v. 2014.1 (KnowWare International Inc, Denver, CO). Data were housed in the Research Electronic Data Capture program hosted at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center.14

Results

Patient Characteristics

During the 2 periods, clinicians performed 584 intubations in the NICU. Outcome data were available for 273/304 (89.8%) intubations during period 1 and 236/280 (84.3%) intubations during period 2. Patient, provider, and practice characteristics between the 2 periods are shown in Table 1. Infants intubated in period 2 were younger, more likely to be on continuous positive airway pressure/noninvasive positive pressure ventilation versus high-flow nasal cannula, more likely to be intubated by a less experienced provider, and more likely to be nonemergently intubated. Some of these differences may be explained by an ongoing project in our NICU to increase the use of continuous positive airway pressure in preterm infants.

TABLE 1.

Clinical Variables of Intubations by Study Period

| Variable | Period 1 (n = 273 Intubations) | Period 2 (n = 236 Intubations) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postnatal age, median d [IQR] | 14 [1–45] | 2 [1–20.5] | <.001 |

| Postmenstrual age, median wk [IQR] | 32 [29–38] | 32 [28–38] | .46 |

| Wt, median g [IQR] | 1560 [1010–2870] | 1758 [1010–2995] | .67 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 170 (62.3) | 130 (55.1) | .1 |

| Craniofacial anomaly,a n (%) | 10 (4) | 16 (7) | .11 |

| Fio2 before intubation, median [IQR] | 46 [32–68] | 43 [30–60] | .06 |

| Respiratory support immediately before intubation, n (%) | |||

| Mechanical ventilator | 71 (26) | 57 (24) | .01* |

| CPAP/NIPPV | 85 (31) | 111 (47) | |

| High-flow nasal cannula | 97 (36) | 58 (25) | |

| Nasal cannula | 6 (2) | 5 (2) | |

| Room air | 10 (4) | 4 (2) | |

| Headbox | 4 (1) | 1 | |

| Any premedication use, n (%) | 201 (73.6) | 204 (86.4) | <.001 |

| Opiate use | 192 (70.3) | 200 (84.8) | <.001 |

| Benzodiazepine use | 123 (45.1) | 50 (21.2) | <.001 |

| Muscle relaxant use | 16 (5.9) | 31 (13.1) | .005 |

| Intubation attempts, median [IQR] | 2 [1–3] | 2 [1–3] | .49 |

| Proceduralist on first attempt, n (%) | |||

| Resident | 36 (13.2) | 45 (19.2) | .33* |

| Neonatology fellow | 122 (44.7) | 97 (41.3) | |

| NNP/hospitalist | 104 (38.1) | 83 (35.3) | |

| Otherb | 11 (4) | 10 (4.3) | |

| Self-reported experience level of first attempt proceduralists, n (%) | |||

| <10 attempts | 41 (15.1) | 60 (25.5) | .001* |

| 10–40 attempts | 104 (38.2) | 60 (25.5) | |

| >40 attempts | 127 (46.7) | 115 (49) | |

| Intubation urgency, n (%) | |||

| Elective | 72 (26.6) | 77 (32.8) | .04* |

| Urgent | 170 (62.7) | 146 (62.1) | |

| Emergent | 29 (10.7) | 12 (5.1) | |

CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; Fio2, fraction of inspired oxygen; NIPPV, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation; NNP, neonatal nurse practitioner.

Craniofacial anomalies include cleft lip, cleft palate, choanal atresia or stenosis, and Pierre Robin syndrome.

Other proceduralists include attending neonatologists, respiratory therapists, anesthesiologists, otolaryngologists, and NNP students.

P value for the entire covariate.

Outcome Measures

One or more AEs occurred in 126/273 (46%) intubations during period 1 and 85/236 (36%) intubations during period 2, a statistically significant reduction (RR = 0.78; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.63–0.97). Secondary outcomes of bradycardia and hypoxemia during intubation were also significantly lower during period 2 (Table 2). Bradycardia during intubation declined from 66/273 (24.2%) in period 1 to 22/236 (9.3%) in period 2 (RR = 0.39; 95% CI, 0.25–0.61). Hypoxemia during intubation declined from 121/273 (44.3%) in period 1 to 78/236 (33.1%) in period 2 (RR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.6–0.93).

TABLE 2.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes by Study Period

| Period 1 (n = 273 Intubations) | Period 2 (n = 236 Intubations) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any AE | 126 (46.2) | 85 (36) | .02 |

| Nonsevere or severe event | 107 (39.2) | 72 (30.5) | .04 |

| Any severe event | 24 (8.8) | 15 (6.4) | .3 |

| Hypotension receiving intervention | 10 (3.7) | 3 (1.3) | .09 |

| Transition to emergent | 9 (3.3) | 8 (3.4) | .95 |

| Chest compressions | 8 (2.9) | 4 (1.7) | .36 |

| Code medications | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.9) | 1 |

| Direct airway trauma | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 |

| Pneumothorax | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 |

| Deatha | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 |

| Esophageal intubation with delayed recognition | 0 | 0 | — |

| Any nonsevere event | 96 (35.2) | 66 (27.9) | .08 |

| Esophageal intubation with immediate recognition | 58 (21.3) | 34 (14.4) | .05 |

| Oral or airway bleeding | 26 (9.5) | 17 (7.2) | .35 |

| Difficult bag-mask ventilation | 20 (7.3) | 10 (4.2) | .14 |

| Mainstem bronchial intubation | 19 (7) | 13 (5.5) | .5 |

| Emesis | 6 (2.2) | 4 (1.7) | .76 |

| Chest wall rigidity | 3 (1.1) | 4 (1.7) | .7 |

| Any procedural event | 42 (15.4) | 27 (11.4) | .2 |

| Pain or agitation necessitating additional medications | 23 (8.4) | 20 (8.4) | .98 |

| Equipment failure | 9 (3.3) | 2 (0.85) | .06 |

| Needed equipment not at bedside during intubation | 15 (5.5) | 6 (2.5) | .1 |

| Bradycardia | 66 (24.2) | 22 (9.3) | <.001 |

| Hypoxemia | 121 (44.3) | 78 (33.1) | .006 |

All data are displayed as n (%).

Infant with unilateral pulmonary interstitial emphysema who had bradycardic arrest during elective endotracheal tube exchange.

Using statistical process control methods, we identified special cause variation in the percentage of intubations with an AE with a shift of 8 subgroups below the center line starting in subgroup 11 (Fig 1). This corresponded to the beginning of intervention 1, use of our Intubation Timeout tool. We also observed special cause variation in the percentage of infants who had bradycardia during intubation (Fig 1). Although we noted a significant decrease in hypoxemia in period 2 by using classic statistical methods, we detected no special cause variation by using a p-chart (Fig 1).

FIGURE 1.

P-charts showing (A) percentage of intubations with a documented AE, (B) percentage of intubations with documented bradycardia, and (C) percentage of intubations with documented hypoxemia. CL, center line; LCL, lower control limit; UCL, upper control limit.

Process Measures

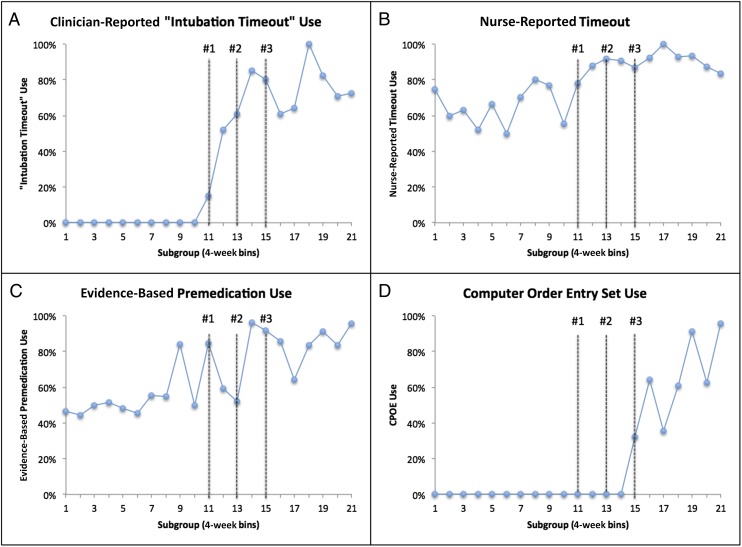

Process measures for our 3 interventions are shown in Table 3. The use of each of our interventions increased throughout period 2 (Fig 2). Although overall compliance with the use of our Intubation Timeout tool during period 2 was 73%, our bedside nurses reported a substantial increase in the number of intubations during period 2 when the team performed a formal timeout (with or without the Intubation Timeout tool). We noted a qualitative shift in the way the Intubation Timeout tool was used during intervention and sustainment. We created the tool to be used as a do–confirm checklist10 led by the intubating clinician immediately before intubation. During the sustainment period, through our direct observations and semistructured interviews, we noted an increase in the use of the checklist as a read–do checklist,10 when a bedside nurse read aloud the components of the Intubation Timeout tool and members of the team either completed the tasks or answered the questions.

TABLE 3.

Process and Balancing Measures for the Interventions

| Period 1 | Period 2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process measures | |||

| Clinician reported use of Intubation Timeout tool, n (%)a | N/A | 161/221 (73) | — |

| Nurse-reported team timeout, n (%)a | 128/191 (67) | 148/165 (90) | <.001 |

| Use of evidence-based premedication, n (%) | 150/273 (55) | 191/236 (81) | <.001 |

| Use of CPOE order set, n (%) | N/A | 100/166 (60) | — |

| Balancing measures | |||

| Time from decision to intubate to tube secured, median min [IQR] | 27 [18–45] | 33 [22–51] | .01 |

| Infants decompensating while awaiting premedications from pharmacy, n (%) | 1/273 (0.4) | 1/236 (0.4) | 1 |

| Medication errors, n (%) | 1/273 (0.4) | 2/236 (0.9) | .6 |

| Potential medication side effects | |||

| Hypotension, n (%) | 10/273 (3.7) | 3/236 (1.3) | .1 |

| Chest wall rigidity (associated with opiate administration), n (%) | 3/273 (1.1) | 4/236 (1.7) | .7 |

| Inability to extubate after INSURE procedure, n (%) | Not measured | 1/17 (6) | — |

N/A, not applicable.

Measures not reported for all eligible intubations.

FIGURE 2.

P-charts of all process measures. A, Clinician-reported use of the Intubation Timeout before intubations. B, Nurse-reported use of any timeout with the full team present before the intubation. C, Evidence-based premedication regimen used before intubation. D, Computerized intubation order set used.

Balancing Measures

As anticipated, our interventions were associated with an increase in the amount of time from the decision to intubate to the time the endotracheal tube was secured (median 27, interquartile range [IQR] [18–45] vs 33 minutes IQR [22–51]; P = .01) (Supplemental Fig 5). However, we did not see an increase in the number of infants who had clinical decompensation while awaiting intubation. Shortly after implementation of our premedication algorithm, we observed 2 episodes of atropine overdose. Upon investigation, we found that our CPOE system contained a feature that recommended a 0.1-mg minimum dose of atropine, higher than recommended for most infants in the NICU.15 After making changes to our CPOE system, we observed no more medication errors. During the project, clinicians expressed concern that premedication in preterm infants before the intubation–surfactant–extubation (INSURE) procedure might delay extubation. We therefore followed this procedure as a balancing measure in our last 97 intubations during the sustainment period. Of these intubations, 17 were performed for surfactant administration. Only 1 of these infants could not be extubated immediately after surfactant administration but was extubated 5 hours later. The medical team could not identify a specific reason for the delayed extubation. Additional balancing measures can be seen in Table 3.

Discussion

We have shown that our quality improvement interventions significantly improved the safety of neonatal endotracheal intubation by decreasing the incidence of intubation-associated AEs. Use of our Intubation Timeout tool, consisting of a standardized checklist and prebrief script, was temporally associated with a 10% absolute reduction in AEs that was sustained over the observation period. In addition, improving the quality of premedication for intubation by implementation of a premedication algorithm and computerized order entry set was associated with a significant decrease in the incidence of bradycardia.

The immediate and sustained decrease in the incidence of AEs after implementation of our Intubation Timeout occurred despite the fact that we achieved only a 73% clinician-reported compliance rate with our tool. Although compliance was lower than anticipated, the increased percentage of nurses who reported performing a timeout as a team during period 2 suggested improved team communication before intubations. We also noted a qualitative shift in how our Intubation Timeout was used over the course of the project, from a clinician-led do–confirm checklist to a nurse-led read–do format. Checklists in health care are often complex social interventions consisting of items to promote communication, teamwork, situational awareness, and straightforward equipment checks.16 Our Intubation Timeout is typical of these checklists, with simultaneous implementation of multiple interventions (equipment checklist, procedural briefing to improve team communications, pause-point to ensure that all personnel are ready). Because of our project design and the pragmatic process measures we used, we are unable to explain definitively the mechanism for the improvement seen. It is possible that the act of performing the checklist as a team before intubation was more important than the specific items on the tool, or who led its use. Future studies are needed to understand the mechanisms for improvement with our tool and its applicability in other NICUs.

Although implementation of our premedication algorithm increased the frequency of use of evidence-based premedication, we did not observe temporal improvement in our AEs. One explanation for this finding may be our NICU’s infrequent use of muscle relaxants. Although our algorithm advocated the use of muscle relaxants in appropriate infants, this step was not mandated. In an observational study, use of muscle relaxants was associated with reduction in the rate of intubation-associated AEs.3 In addition, randomized trials have shown that muscle relaxants used for intubation decreased both the number of attempts and total procedure time.17–19 We previously showed that the incidence of AEs was directly related to the number of attempts.4 Although we found that infants were more likely to receive muscle relaxants during period 2 than previously, probably as a result of our algorithm and CPOE (Table 1, from 5.9% to 13.1%), use still remained low. As in most US NICUs, our center’s premedication regimen has not historically included muscle relaxants.20 We anticipate that future interventions to increase the appropriate use of muscle relaxants will improve the safety of neonatal intubation by decreasing the overall number of attempts.

An important part of any quality improvement project is the sustainability of the interventions and measurements.21 We noted a steady increase in the use of our interventions throughout period 2, even after each intervention and the cessation of the associated staff education (Fig 2). We think that our effort to understand the workflow in our unit as we designed our interventions, including process flow mapping and provider interviews, were valuable in ensuring that our interventions were integrated into the workflow of the unit and would be sustained. After the formal project period, all 3 interventions remain in use. However, our data collection, which depends on documentation by clinicians, decreased slightly during period 2 (from 89.8% to 84.3%), indicating that this process is probably not sustainable. We are exploring methods to integrate data acquisition into the electronic medical record, thereby ensuring data collection for ongoing monitoring and improvement.

Our project has some limitations. First, we relied on provider report for many of our measures. Although we attempted to validate these measures where possible, our reliance on self-report may have led to information bias and subsequent misclassification. Second, given our project design, we are not able to definitively conclude that our interventions resulted in the reductions in AEs. However, our use of a time series design strengthens the case that our Intubation Timeout tool led to the reductions seen. Third, we were able to collect data on only 89.8% and 84.3% of intubations during periods 1 and 2, respectively. Finally, the improvement we observed in our NICU may not be generalizable to all NICUs.

Conclusions

We have shown that specific quality improvement interventions reduced the rate of AEs associated with endotracheal intubation in the NICU, substantially improving patient safety. Implementation of our Intubation Timeout tool resulted in the largest reduction in AEs, an absolute reduction of 10%. Future work is needed to better understand mechanisms for the observed improvements and to demonstrate the reproducibility of our findings in other NICU settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the respiratory therapists, bedside nurses, nurse practitioners, and physicians who collected data, generated the ideas for improvement, and took part in the improvement initiatives.

Glossary

- AE

adverse event

- CI

confidence interval

- CPOE

computerized provider order entry

- INSURE

intubation–surfactant–extubation

- IQR

interquartile range

- IV

intravenously

- RR

risk ratio

Footnotes

Dr Hatch conceptualized and designed the project, designed and assisted in implementing the interventions, supervised the data collection process, analyzed the data, and drafted the initial manuscript; Drs Grubb, Walsh, Markham, Maynord, Whitney, and Stark assisted with project design and data collection instruments, assisted in designing the intervention, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms Lea assisted with the design of the data collection instruments and interventions, assisted in the data collection process, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Ely assisted with the project design and data collection instruments, assisted with the design of the data analysis, assisted in designing the intervention, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Dr Hatch was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant 5T32HD068256-02 and the John and Leslie Hooper Neonatal–Perinatal Endowment Fund. Use of the Research Electronic Data Capture program was supported by grant UL1 TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Snijders C, van Lingen RA, Molendijk A, Fetter WP. Incidents and errors in neonatal intensive care: a review of the literature. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92(5):F391–F398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, et al. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2114–2120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foglia EE, Ades A, Napolitano N, Leffelman J, Nadkarni V, Nishisaki A. Factors associated with adverse events during tracheal intubation in the NICU. Neonatology. 2015;108(1):23–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatch LD, Grubb PH, Lea AS, et al. Endotracheal intubation in neonates: a prospective study of adverse safety events in 162 infants. J Pediatr. 2016;168:62–66.e66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharek PJ, Horbar JD, Mason W, et al. Adverse events in the neonatal intensive care unit: development, testing, and findings of an NICU-focused trigger tool to identify harm in North American NICUs. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1332–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishisaki A, Turner DA, Brown CA III, Walls RM, Nadkarni VM; National Emergency Airway Registry for Children (NEAR4KIDS); Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network . A National Emergency Airway Registry for children: landscape of tracheal intubation in 15 PICUs. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(3):874–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nett S, Emeriaud G, Jarvis JD, Montgomery V, Nadkarni VM, Nishisaki A; NEAR4KIDS Investigators and Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network . Site-level variance for adverse tracheal intubation–associated events across 15 North American PICUs: a report from the National Emergency Airway Registry for Children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(4):306–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langley GJ, Moen RD, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flin R, Maran N. Basic concepts for crew resource management and non-technical skills. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2015;29(1):27–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gawande A. The Checklist Manifesto. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar P, Denson SE, Mancuso TJ; Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine . Premedication for nonemergency endotracheal intubation in the neonate. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):608–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Speroff T, O’Connor GT. Study designs for PDSA quality improvement research. Qual Manag Health Care. 2004;13(1):17–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montgomery DC. Introduction to Statistical Quality Control. 7th ed New York, NY: Wiley; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrington KJ. The myth of a minimum dose for atropine. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):783–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catchpole K, Russ S. The problem with checklists. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(9):545–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrington KJ, Finer NN, Etches PC. Succinylcholine and atropine for premedication of the newborn infant before nasotracheal intubation: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 1989;17(12):1293–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dempsey EM, Al Hazzani F, Faucher D, Barrington KJ. Facilitation of neonatal endotracheal intubation with mivacurium and fentanyl in the neonatal intensive care unit. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006;91(4):F279–F282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feltman DM, Weiss MG, Nicoski P, Sinacore J. Rocuronium for nonemergent intubation of term and preterm infants. J Perinatol. 2011;31(1):38–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muniraman HK, Yaari J, Hand I. Premedication use before nonemergent intubation in the newborn infant. Am J Perinatol. 2015;32(9):821–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(6):543–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]