Abstract

Objectives:

To study medicine prescribing pattern for chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients on maintenance hemodialysis.

Materials and Methods:

This prospective observational study was conducted in hemodialysis unit of a teaching hospital with adult CKD patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Patients’ clinical profile, drug-use pattern, and medication-related problem data were captured in a structured case report form and the data were analyzed descriptively. Adherence level was assessed by Morisky Medication-Taking Adherence Scale 4-item.

Results:

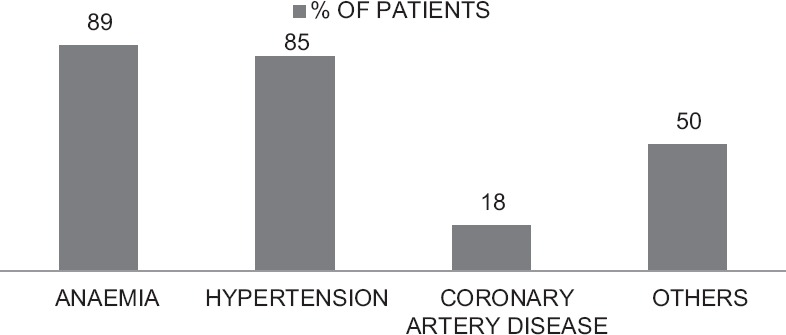

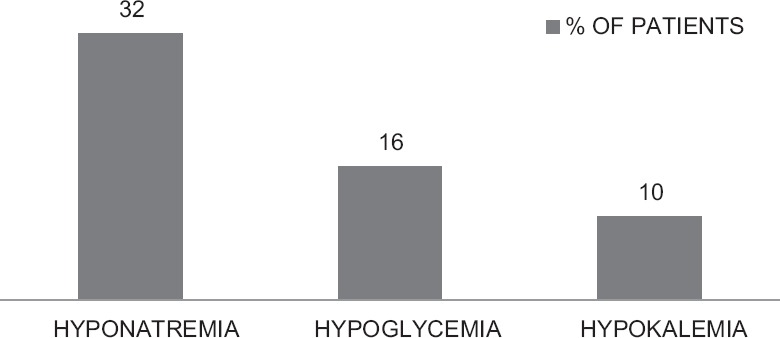

Data from 100 patients recruited over 6 months have been analyzed. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) age was 51 (42–57) years; 57% were male, mean [standard deviation (SD)] urea level was 160.11 (70.32) mg/dL, mean (SD) creatinine level was 8.73 (5.29) mg/dL. A large number (46%) were suffering from diabetic nephropathy. The common comorbidities were anemia (89%) followed by hypertension (85%). The median (IQR) number of drugs per prescription was 10 (9–13), with the bulk being cardiovascular drugs (23.41%) followed by gastrointestinal drugs (15.76%) and vitamins (12.29%). The median (IQR) number of potential drug-drug interaction per prescription was 2 (2–3). The incidence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) was 46% with hyponatremia being most common (32%), followed by hypoglycemia (16%) and hypokalemia (10%). Adherence level was low in the majority (64%) of patients.

Conclusions:

There is a high incidence of polypharmacy along with significant medication-related problems such as high drug-drug interactions/prescription, high incidence of ADRs, and low adherence.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, diabetic nephropathy, hemodialysis, medication adherence, prescribing patterns

Chronic kidney disease (CKD), characterized by progressive decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), is a major public health issue worldwide and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.[1] India, with its huge diabetic and hypertensive population, is becoming a major reservoir of CKD. The therapy of CKD and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is very expensive and out of the reach of more than 90% of patients in India.[2]

Chronic hemodialysis patients have multiple complications requiring pharmacologic therapy, and ESRD may heighten the risk of unfavorable drug effects. The administration of multiple medications as well as poor compliance with drug regimens and drug interactions may contribute to drug-related problems. Despite the frequent use of multiple medications and the high potential of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), the current information on the types and numbers of drugs prescribed for Asian hemodialysis patients is sparse.[3]

Noncompliance with drug regimens may increase the risk of severe complications and represents a potential problem in hemodialysis patients who are on multiple medicines. Although the number of prescribed medications in hemodialysis patients may be associated with mortality, this relationship has not yet been examined.[3]

Appropriate drug selection for patients with CKD is important to avoid unwanted drug effects and to ensure optimal patient outcomes. Rational drug prescription is difficult in CKD patients due to a higher risk of drug-related problems since they need complex therapeutic regimens requiring frequent monitoring and dosage adjustments. The presence of other comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and infections make the situation more complicated. Inappropriate medication use can increase adverse drug effects as reflected in prolonged hospital stays, increased health care utilization and costs.[4]

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a microvascular complication of both insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. It is characterized by persistent proteinuria, decline in GFR, and increased morbidity and mortality. Studies have suggested that the prevalence of DN is approximately 40% in diabetic patients, and DN is the most common cause of ESRD. It is very difficult to select, initiate, and individualize appropriate drug therapy for DN patients. Prescribing patterns are often studied to monitor and evaluate prescribing practices to recommend necessary modifications toward the achievement of rational drug use.[5]

The management of DN includes good glycemic control, tight control of blood pressure, and reduction of proteinuria, along with cessation of smoking, lipid control, and salt and protein restriction. Therapeutic intervention is intended to prevent or retard the progression of the diabetic renal disease as well as to reduce cardiovascular complications.[6]

Drug utilization studies are conducted frequently all over the world; however, in India, there is no clear picture of overall medication profile in CKD patients. With constraints of a limited health budget, it becomes meaningful to prescribe drugs rationally. In this context, the current study was planned to assess the situation and detect the areas for improvement. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies in this aspect in the past 5 years from Eastern India.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional observational study was conducted at the Hemodialysis Unit of R. G. Kar Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, from September 2014 to February 2015. The Institutional Ethics Committee approval was obtained for data collection.

Over a period of 6 months, 100 CKD patients of either sex and aged over 18 years, on maintenance hemodialysis, who had given written informed consent were included in the study. Terminally ill patients who were not in a position to be interviewed were excluded from the study. Sampling was purposive.

Patients’ clinical profile, drug usage patterns, and medication-related problem data were captured in a structured case report form. Where necessary, the information was cross-checked with the help of recent medical records. Suspected ADRs were recorded in the format recommended by the Pharmacovigilance Programme of India. Adherence level was assessed by Morisky Medication-Taking Adherence Scale 4-item[7] scale administered through a face-to-face interview. Drug-drug interactions (DDIs) were checked with MedScape multidrug interaction checker (http://reference.medscape.com/drug-interactionchecker).

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 5 (2007, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, California, USA) software. Summary statistics were expressed using mean and standard deviation (SD) for numerical variables (median and interquartile ranges [IQRs] when skewed) and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Numerical variables were compared between subgroups by Mann–Whitney U-test. Fisher's exact test was employed for intergroup comparison of categorical variables. The median number of DDIs with increasing number of drugs per prescription categories was assessed for statistical significance by Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA. Comparisons were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Totally, 100 individuals agreed to participate in the study out of 131 approached, giving a nonresponder rate of 23.66%.

Of the 100 respondents, 57% were male. The median age was 51 with IQR 42–57 years. The number of hemodialysis sessions per patient was 4.5 (IQR 3–8). The incidence of DN was 46%. The average urea level was 160.11 (SD 70.32) mg/dL and creatinine level was 8.73 (SD 5.29) mg/dL.

The major comorbidities are summarized in Figure 1. The most common comorbidity was anemia (89%) followed by hypertension (85%).

Figure 1.

Frequency of comorbidities

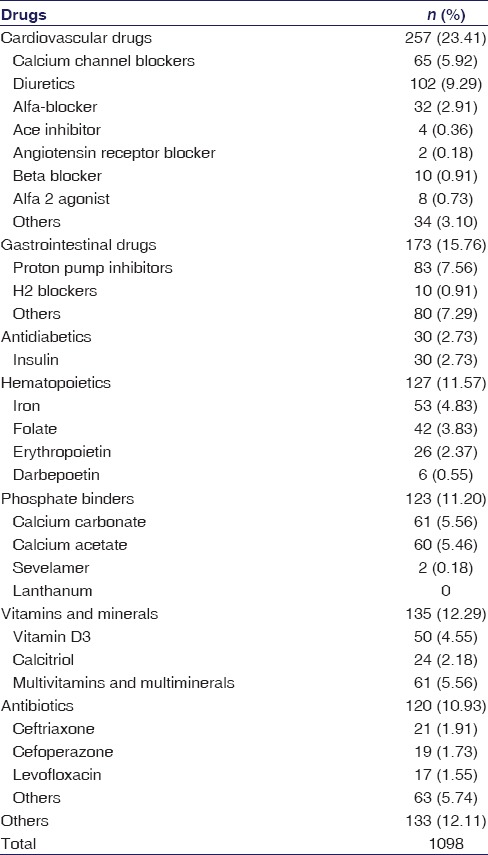

A total of 1098 drugs were prescribed for these 100 patients. The drugs prescribed are summarized in Table 1. The median number of drugs per prescription was 10 (IQR 9–13). The number of drugs per prescription was higher in diabetic patients (11 [IQR 9–13.75]) than in nondiabetic patients (10 [IQR 9–12.75]) on hemodialysis. However, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.118). Cardiovascular drugs were most commonly used (23.41%), followed by gastrointestinal system drugs (15.76%), vitamins and minerals (12.29%). The five most commonly used drugs/drug classes were diuretics (9.29%), proton pump inhibitors (7.56%), calcium channel blockers (CCBs) (5.92%), multivitamins and calcium carbonate (5.56), and calcium acetate (5.46%).

Table 1.

Drug usage pattern in 100 chronic kidney disease patients on maintenance hemodialysis

Antibiotics were administered to 78% of these patients. There was no statistically significant difference in antibiotic usage in diabetics (86.96%) versus nondiabetics (70.37%) (P = 0.055). We were unable to decipher a clear clinical indication for antibiotic usage in 64 (82.05%) cases.

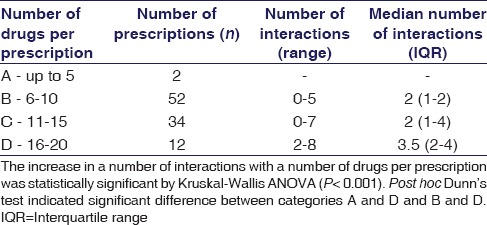

The prevalence of potential DDIs was 82%. The median number of potential DDIs per prescriptions was 2 (IQR 2–3) and the number of interactions increased with increasing number of drugs per prescription as depicted in Table 2. This difference was highly statistically significant (P < 0.001). Some of the potentially interacting combinations were levofloxacin–insulin, levofloxacin–ondansetron, escitalopram–ondansetron, and metronidazole–theophylline.

Table 2.

Potential drug-drug interactions per prescription among 100 chronic kidney disease patients on maintenance hemodialysis

The incidence of ADRs was 46%, hyponatremia being most common (32%), followed by hypoglycemia (16%) and hypokalemia (10%) [Figure 2]. In this count, we included only events that were potentially related to drugs required for managing CKD and excluded those related to drugs for comorbidities not related to kidney disease, for example, osteoarthritis of knees. The causality relationship was assessed by the World Health Organization-Uppsala Monitoring Centre criteria, excluding those events that could be related to the comorbidity rather than prescribed drugs. Severe symptomatic hyponatremia (12 [37.5%]) was treated with diuretic dose modification and/hypertonic saline; however, others (20 [62.5%]) were treated by recommending extra salt in the diet. Hypokalemia was moderate in nature, treated by diuretic dose reduction. Hypoglycemia was treated with intravenous 25% dextrose and dose adjustment or omission of insulin.

Figure 2.

Frequency of adverse drug reactions

Adherence level was high in 9%, medium in 27% but low in the majority (64%) of patients.

Discussion

The results of the study revealed male predominance (57%) and average age to be more than 50 years which is similar to the previous study.[8] The median (IQR) number of drugs per prescription was 10 (9–13) which indicates polypharmacy. Polypharmacy has been defined as the use of 5 or more medications to one patient at a time.[8] However, in view of the complex nature and coexisting comorbidities of CKD, some researchers suggest the use of more than 9 drugs at a time to be considered polypharmacy.[8] Inappropriate polypharmacy can lead to significant morbidities and mortality.[9]

Diuretics were most commonly prescribed cardiovascular drugs followed by CCBs. These results are similar to a previous study by Bajait et al., where diuretics were more commonly prescribed than CCBs;[8] however, in other studies, CCBs were most commonly prescribed cardiovascular drugs.[5,10]

In spite of high prevalence of anemia (89%), erythropoietin-stimulating agents (ESA) such as erythropoietin and darbepoetin were used to a limited extent (32%). The use of ESAs in anemic CKD patients subsequently reduces blood transfusion requirements.[11]

Among 46 DN patients, only 30 (65.22%) received antidiabetic medication; 16 (34.78%) of them were not on any antidiabetic medication. These observations support the hypothesis that in CKD, the requirement of insulin falls leading to a subsequent reduction in antidiabetic drug prescription. Insulin was the only prescribed antidiabetic drug. Oral antidiabetic drugs were not used. They can precipitate serious hypoglycemia or metabolic acidosis in CKD patients. These findings were similar to previous studies.[5]

Of all prescribed drugs, 11.20% were phosphate binders (PB). Calcium carbonate was the most frequently prescribed PB, followed by calcium acetate and sevelamer. These findings were similar to the previous study.[8] Sevelamer, being a nonabsorbable calcium-free PB, is associated with reduced cardiovascular calcification compared to calcium-based PBs.[12] A recent meta-analysis showed 22% reduction in all-cause mortality in CKD patients, who are on calcium-free PBs, compared to calcium-based PBs.[13] However, its high cost may be the reason for its low utilization compared to calcium-based PBs. Lanthanum was not encountered in this series.

Antibiotics may well be required in CKD patients for reasons such as urinary or respiratory tract infections. However, since many antibiotics are renally eliminated and some may be nephrotoxic in nature, careful antibiotic drug and dose selection are necessary. The lack of a clear indication for antibiotic therapy in 82.05% cases is, therefore, a matter of concern.

The number of prescriptions with potential DDIs in our study was high at 82%. This is comparable to earlier studies.[14,15] However, the median number of DDIs per prescription was also high and increased progressively with an increasing number of drugs per prescription. Polypharmacy is a likely contributor to the high number of potential DDIs per prescription.

We have captured events while the patient was observed as the part of study and those recorded in medical records or hospital bed-head tickets for 2 weeks before admission or OPD visit; therefore, it is more appropriate to refer to incidence rate rather than prevalence rate of ADRs, considering events occurring within last 14 days as recent rather than old events.

Hyponatremia was the most common ADR documented in our series, followed by hypoglycemia and hypokalemia. We excluded events such as nausea, constipation, lethargy, and muscle weakness as these could have resulted from underlying morbidities rather than prescribed drugs and cannot be documented clearly through laboratory testing. The incidence of hyponatremia was 32%. Although CKD itself can precipitate hyponatremia due to impaired water homeostasis,[16] it is more likely to be the result of the injudicious use of diuretics. In a US population-based study, the point prevalence of hyponatremia was 13.5% and it was similar in ESRD patients.[17] Hyponatremia increases mortality in nondialysis-dependent,[17] hemodialysis-dependent, and peritoneal dialysis-dependent[18] CKD patients. The high incidence emphasizes the importance of judicious selection of diuretic dose and regular monitoring.

The incidence of hypoglycemia was 16%. In a previous American study, the incidence was 10.72%.[19] Hypoglycemia in CKD is more likely to be a complication of insulin use rather than resulting from the renal disease per se. Hypoglycemia also increases mortality in CKD patients[19,20] and, therefore, plasma glucose levels require strict monitoring.

Hypokalemia affected 10% of the patients and is likely to be an ADR to diuretic therapy. Hyperkalemia is much more implicated in arrhythmias and their associated mortality than hypokalemia in CKD patients.[21] However, hypokalemia has also been implicated as a strong risk factor for precipitating arrhythmias, including lethal ones.[22,23] Hence, careful attention to monitoring serum potassium levels is vital.

Adherence level was low in our study which conflicts with the seriousness of the disease. However, other authors have also reported a similar experience. An American study by Chiu et al. indicated the prevalence of nonadherence to be 62%.[24] However, Cukor et al. suggested that 39% were perfectly adherent, followed by 25% nearly perfect and 37% less than perfect adherence by medication therapy adherence scale.[25] The likely factors contributing to poor adherence could be frequent dosing, lack of motivation, lack of family and social support, poor socioeconomic status, poor patient–physician communication, and younger age. Poor adherence in CKD patients is associated with treatment failure, additional investigations, unnecessary dose adjustments, change in treatment modalities, and avoidable hospitalizations, all of which add to cost and the risk of mortality. It is a general experience that adherence can be improved by simplifying treatment regimens, increasing awareness through education and feedback, and establishing partnership with the patients.[26]

Our study is limited by its sample size, unicentric nature, and hospital-based evaluation. However, it has generated a profile of drug use in Indian CKD patients on hemodialysis that can serve as the basis for future comparisons. It has also identified some areas of concern such as polypharmacy, underuse of ESAs, use of antibiotics without clear indication, high incidence of potential DDIs and ADRs, and poor adherence in general. There is a need for exploring these issues in detail through future drug-use surveys in CKD patients.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jha V, Wang AY, Wang H. The impact of CKD identification in large countries: The burden of illness. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(Suppl 3):iii32–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajapurkar M, Dabhi M. Burden of disease – Prevalence and incidence of renal disease in India. Clin Nephrol. 2010;74(Suppl 1):S9–12. doi: 10.5414/cnp74s009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tozawa M, Iseki K, Iseki C, Oshiro S, Higashiuesato Y, Yamazato M, et al. Analysis of drug prescription in chronic haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:1819–24. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.10.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Ramahi R. Medication prescribing patterns among chronic kidney disease patients in a hospital in Malaysia. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2012;23:403–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devi DP, George J. Diabetic nephropathy: Prescription trends in tertiary care. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2008;70:374–8. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.43007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gross JL, de Azevedo MJ, Silveiro SP, Canani LH, Caramori ML, Zelmanovitz T. Diabetic nephropathy: Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:164–76. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morisky DE, DiMatteo MR. Improving the measurement of self-reported medication nonadherence: Response to authors. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:255–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bajait CS, Pimpalkhute SA, Sontakke SD, Jaiswal KM, Dawri AV. Prescribing pattern of medicines in chronic kidney disease with emphasis on phosphate binders. Indian J Pharmacol. 2014;46:35–9. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.125163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bushardt RL, Massey EB, Simpson TW, Ariail JC, Simpson KN. Polypharmacy: Misleading, but manageable. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:383–9. doi: 10.2147/cia.s2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailie GR, Eisele G, Liu L, Roys E, Kiser M, Finkelstein F, et al. Patterns of medication use in the RRI-CKD study: Focus on medications with cardiovascular effects. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1110–5. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joshi AD, Holdford DA, Brophy DF, Harpe SE, Mays D, Gehr TW. Utilization Patterns of IV Iron and erythropoiesis stimulating agents in anemic chronic kidney disease patients: A multihospital study. Anemia 2012. 2012:248430. doi: 10.1155/2012/248430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Negri AL, Ureña Torres PA. Iron-based phosphate binders: Do they offer advantages over currently available phosphate binders? Clin Kidney J. 2015;8:161–7. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfu139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamal SA, Vandermeer B, Raggi P, Mendelssohn DC, Chatterley T, Dorgan M, et al. Effect of calcium-based versus non-calcium-based phosphate binders on mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382:1268–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rama M, Viswanathan G, Acharya LD, Attur RP, Reddy PN, Raghavan SV. Assessment of drug-drug interactions among renal failure patients of nephrology ward in a South Indian tertiary care hospital. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2012;74:63–8. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.102545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marquito AB, Fernandes NM, Colugnati FA, de Paula RB. Identifying potential drug interactions in chronic kidney disease patients. J Bras Nefrol. 2014;36:26–34. doi: 10.5935/0101-2800.20140006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovesdy CP. Significance of hypo-and hypernatremia in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:891–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovesdy CP, Lott EH, Lu JL, Malakauskas SM, Ma JZ, Molnar MZ, et al. Hyponatremia, hypernatremia, and mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease with and without congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2012;125:677–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.065391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang TI, Kim YL, Kim H, Ryu GW, Kang EW, Park JT, et al. Hyponatremia as a predictor of mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moen MF, Zhan M, Hsu VD, Walker LD, Einhorn LM, Seliger SL, et al. Frequency of hypoglycemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1121–7. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00800209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kong AP, Yang X, Luk A, Cheung KK, Ma RC, So WY, et al. Hypoglycaemia, chronic kidney disease and death in type 2 diabetes: The Hong Kong diabetes registry. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14:48. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-14-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korgaonkar S, Tilea A, Gillespie BW, Kiser M, Eisele G, Finkelstein F, et al. Serum potassium and outcomes in CKD: Insights from the RRI-CKD cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:762–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05850809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Checherita IA, David C, Diaconu V, Ciocâlteu A, Lascar I. Potassium level changes – Arrhythmia contributing factor in chronic kidney disease patients. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2011;52(3 Suppl):1047–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayes J, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Lu JL, Turban S, Anderson JE, Kovesdy CP. Association of hypo-and hyperkalemia with disease progression and mortality in males with chronic kidney disease: The role of race. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120:c8–16. doi: 10.1159/000329511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiu YW, Teitelbaum I, Misra M, de Leon EM, Adzize T, Mehrotra R. Pill burden, adherence, hyperphosphatemia, and quality of life in maintenance dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1089–96. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00290109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cukor D, Rosenthal DS, Jindal RM, Brown CD, Kimmel PL. Depression is an important contributor to low medication adherence in hemodialyzed patients and transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 2009;75:1223–9. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loghman-Adham M. Medication noncompliance in patients with chronic disease: Issues in dialysis and renal transplantation. Am J Manag Care. 2003;9:155–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]