Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy, as well as potential moderators and mediators, of a revised acceptance-based behavioral treatment (ABT) for obesity, relative to standard behavioral treatment (SBT).

Design and Methods

Participants with overweight and obesity (n=190) were randomized to 25 sessions of ABT or SBT over 1 year. Primary outcome (weight), mediator and moderator measurements were taken at baseline, 6 months and/or 12 months, and weight was also measured every session.

Results

Participants assigned to ABT attained a significantly greater 12-month weight loss (13.3% ± 0.83) than did those assigned to SBT (9.8% ± 0.87; p=.005). A condition by quadratic time effect on session-by-session weights (p=.01) indicated that SBT had a shallower trajectory of weight loss followed by an upward deflection. ABT participants were also more likely to maintain a 10% weight loss at 12 months (64.0% vs 48.9%; p=.04). No evidence of moderation was found. Results supported the mediating role of autonomous motivation and psychological acceptance of food-related urges.

Conclusion

Behavioral weight loss outcomes can be improved by integrating self-regulation skills that are reflected in acceptance-based treatment, i.e., tolerating discomfort and reduction in pleasure, enacting commitment to valued behavior, and being mindfully aware during moments of decision making.

Keywords: Weight Loss, Treatment, Obesity, Clinical Trials, Behavior Modification

Introduction

Behavioral weight loss interventions produce weight losses averaging about 5–8% at the end of a 12-month intervention [1]. While these outcomes are robust, a substantial proportion of participants do not achieve clinically significant benefits, and participants lose considerably less weight than individuals whose adherence to dietary prescriptions is ensured via a controlled environment [2–4]. The suboptimal outcomes of behavioral weight control programs are primarily attributable to an inability to meet and/or maintain prescribed dietary intake and physical activity goals, i.e., to inadherence [5, 6].

Adherence to healthy eating and physical activity goals depends on the ability to self-regulate in the face of biological predispositions (e.g., a drive to consume high-calorie food) and the pervasive cues (e.g., the presence of food, television, cravings, anxiety, boredom) that facilitate overeating and sedentary behavior [7]. Standard behavioral interventions for weight loss do not intensively focus on developing skills that teach individuals how to override drives and urges for pleasure or comfort, which may help explain why most individuals lose less weight than desired. Given the pervasive obesogenic food environment, urges and desires to consume calorie-dense, palatable food likely persist for most individuals seeking weight loss.

Acceptance-based behavioral interventions infuse behavioral treatment with strategically chosen self-regulation skills that are adapted primarily from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy [8] but also from Dialectical Behavior Therapy [9] and Relapse Prevention for Substance Abuse [10] These self-regulation skills include an ability to tolerate uncomfortable internal states (e.g., urges, cravings, and negative emotions) and a reduction of pleasure (e.g., choosing to exercise instead of watch TV), behavioral commitment to clearly-defined values (which is posited to increase motivation to persist in difficult weight control behaviors), and metacognitive awareness of decision-making processes [7, 11]. This collection of skills is meant to facilitate adherence to behavioral recommendations for weight loss despite the challenges posed by biological predispositions and cues that push individuals to engage in unhealthy behaviors (or non-behaviors) that impede weight control.

Treatments based on acceptance-based principles have shown promise in analog studies (e.g., abstaining from craved, high calorie foods; [12–14]) and uncontrolled trials [15–18]. Several randomized controlled trials also provide support. In one study, individuals completing a self-selected weight loss program who were randomized to an ACT-based one-day workshop intervention continued to lose weight in the months that followed, whereas those randomized to a waitlist control experienced weight regain [19]. In another trial, women randomized to ACT-based workshops lost more weight than participants assigned to a control condition [20]. In addition, university students at risk for weight gain assigned to eight hours of acceptance-based behavioral intervention experienced weight loss, but those assigned to a control exhibited weight gain [21].

Only one published trial to date has compared acceptance-based behavioral treatment (ABT) of obesity to a gold-standard behavioral weight loss intervention. The Mind Your Health project [22] randomized 128 participants with overweight or obesity to receive thirty sessions of group-based ABT or standard behavioral treatment (SBT) over the course of 40 weeks. Both interventions included the core components of behavioral treatment, e.g., prescriptions for calorie intake and physical activity, self-monitoring of food intake, stimulus control, and problem solving. At post-treatment and at a 6-month follow-up, the advantage of ABT was only statistically significant for participants who received the treatment from weight loss experts (versus student trainees) and for participants with particular vulnerabilities to internal and external cues for overeating, i.e., mood disturbance, elevated responsivity to food cues, and high disinhibition. For example, in the expert-led groups, mean ABT weight loss at follow-up was 11% versus 4.8% for SBT. Participants with greater baseline depressive symptomology lost 11.2% of body weight in ABT versus 4.6% in SBT.

Despite the promise demonstrated in early studies of ABT for weight control, a number of questions remain unanswered. First, virtually all of the evidence supporting ABT for weight control comes from analog studies, open trials or trials with a weak control; only one randomized controlled trial comparing ABT to a gold standard treatment exists at this time. Moreover, the original Mind Your Health trial obtained reliable evidence for the superiority for ABT over SBT only under certain conditions. Additional investigation is needed to establish whether ABT confers a benefit over SBT when delivered by experienced clinicians, and to ensure that the previous effect was not attributable to idiosyncratic effects of clinicians in the Mind Your Health trial. Furthermore, the findings that the benefit of ABT is more pronounced among those with specific vulnerabilities requires replication in a sample that receives the treatment from experienced clinicians. In addition, clinician and supervisor feedback indicated that the ABT treatment protocol was problematic in certain regards (e.g., a missing unifying framework, sometimes lacking integration of acceptance and behavioral skills, overemphasis on tolerating discomfort and not enough on tolerating reduction of pleasure), thus raising the possibility that a revised protocol would produce better results. Finally, initial evidence suggested that the ability to accept psychological experiences of reduced pleasure and discomfort related to food choices mediated the effect of ABT. However, no previous study has examined whether the values component of ABT also mediates the effect of ABT for weight control. Thus, it is necessary to test whether these postulated unique mechanisms of action underlie ABT.

In order to investigate the questions posed above, the current study randomized 190 participants with overweight or obesity to either a standard behavioral or an acceptance-based behavioral weight loss intervention. Both interventions were delivered in 25 group sessions over one year, and were delivered by experienced weight control clinicians. We hypothesized that ABT would produce greater weight loss at 12 months compared to SBT, and, consistent with previous findings, the effect of ABT would be most pronounced for those with the particular vulnerabilities described above (i.e., mood disturbance, responsivity to food cues, and disinhibited eating). Lastly, we hypothesized that food-related psychological acceptance and autonomous motivation would mediate the effect of ABT given that these are posited to be two of the central mechanisms of action of the treatment.

Methods

Participants

Participants (n=190) had a body mass index [BMI] between 27–50 kg/m2 and were between 18–70 years of age. Participants were excluded if they had a medical or psychiatric condition that limited their ability to comply with the behavioral recommendations of the program or posed a risk to the participant during weight loss, were unable to engage in the program’s exercise plan, changed the dosage of weight-affecting medication within the past three months, were pregnant or planned to become pregnant during the study period, had lost more than 5% of their weight in the past 6 months,, or met criteria for binge eating disorder.

Procedure

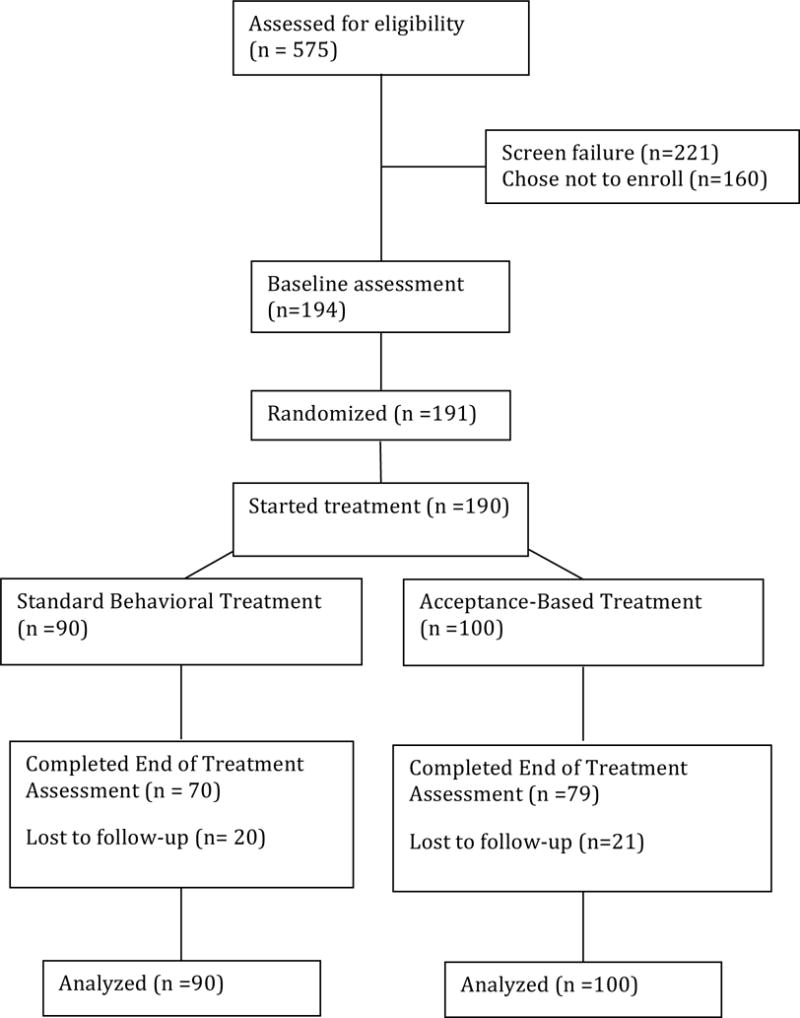

Recruitment for the current study was conducted in four waves of 38 – 45 participants (making up approximately four treatment groups). Potential participants were recruited through referrals from local primary care physicians and advertisements in newspapers and radio stations. Initial screens for eligibility were conducted via telephone. Participants who appeared eligible were invited for two in-person appointments to complete screening and baseline assessment procedures. All participants provided informed consent. Once enrolled, participants were randomly assigned to SBT (n=90) or ABT (n=100). Randomization was stratified by gender and ethnicity. Assessments were completed at months 0 (baseline), 6 (midpoint) and 12 (post-treatment). See Figure 1 for a CONSORT diagram. The study protocol was approved by the Drexel University Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

Intervention

Participants attended 25 treatment groups in total. Treatments were manualized and groups were held weekly for 16 sessions, biweekly for 5 sessions, monthly for 2 sessions, and bi-monthly for 2 sessions. Treatment was delivered in 75-minute, small (10–14 participants), closed-group sessions. Groups typically consisted of brief individual check-ins (35 minutes), skill presentation, and a skill building exercise. If a participant was absent from group, a 20-minute individual make-up session was scheduled to cover material that was missed. Interventionists were doctoral-level clinicians with an average of 4.8 years of experience delivering behavioral weight loss treatment. All interventionists delivered an equal number of SBT and ABT groups. Trainees functioned as group co-leaders.

Treatment

Shared treatment components

Behavioral components of both treatments (e.g., daily self-monitoring of calorie intake, prescriptions for a balanced-deficit diet and physical activity, stimulus control, problem solving) were similar to those used in Look AHEAD and the Diabetes Prevention Program protocols [23, 24]. See Table 1 for a description of components for all treatments.

Table 1.

Components of standard behavioral and acceptance-based behavioral treatments

| Shared components of SBT and ABT | Included only in SBT | Included only in ABT |

|---|---|---|

| Nutritional education, 1200–1800 calorie goal (depending on weight and personal preferences), | Distraction and confrontation | Values clarification; ongoing commitment |

|

| ||

| Physical activity education, gradual increases up to 250 minutes per week of aerobic activity | Identification of cognitive distortions | Mindful decision making training |

| Setting specific, reasonable, actionable, and time-limited goals related to eating or activity behavior | Cognitive restructuring | Psychological acceptance of, and willingness to experience less pleasurable or comfortable states |

| Self-monitoring of caloric intake and physical activity | ||

| Stimulus control (e.g., removal of problematic foods from home/work) | ||

| Behavior analysis (e.g., reviewing factors leading to a lapse in eating or activity goals) | ||

| Relapse prevention (e.g., identifying triggers for overeating/sedentary behavior, creating plan for small weight gains) | ||

| Problem solving (e.g., identifying barriers to healthy eating and activity and developing solutions to overcome) | ||

| Social support (e.g., communicating needs, building positive support) | ||

SBT-only components

Components of SBT not included in ABT were introduction of the traditional cognitive-behavioral model, which indicates that changing the content of one’s thoughts can produce behavior change; cognitive restructuring; building self-efficacy and positive self-esteem; and learning to cope with food cravings through distraction.

Acceptance-based Treatment components

The ABT materials were adapted from those used in the first Mind Your Health study (MYH I), which themselves represented a synthesis of traditional behavioral weight loss treatment and several acceptance-based treatments, i.e., Dialectical Behavior Therapy [9], Marlatt’s Relapse Prevention Model [10] and especially Acceptance and Commitment Therapy [25]. The ABT sessions used for the current study largely emphasized the following principles: (1) participants must choose goals that emanate from freely-chosen, personal life values (e.g. living a long and healthy life; being a present, loving, active grandmother); (2) participants must recognize that, in the context of the obesogenic environment, weight control behaviors will inevitably produce discomfort (urges to eat, hunger, cravings, feelings of deprivation, fatigue) and a reduction of pleasure (choosing an apple instead of ice cream, choosing a walk instead of watching TV); and (3) participants will benefit from increased awareness of the how cues impact their eating and activity-related decision-making.

Based on feedback from clinicians and clinicians’ supervisors, the MYH I manual was adapted in several ways. For example, a “Control What You Can and Accept What You Can’t” framework was used to orient participants to the aspects of their experience that can and should be directly modified (their personal food environment and their behaviors) and those aspects of their experience which are not under voluntary control (e.g., thoughts, emotions, urges) and towards which direct attempts to control will result in wasted effort or even paradoxical magnification. Acceptance-based skills were also more tightly integrated within behavioral weight loss principles by framing behavioral skills and challenges within the context of ABT. For example, participants who avoided self-weighing were taught to be willing to accept difficult thoughts (“I am never going to lose this weight”) and emotions (shame) while simultaneously stepping on the scale. (In contrast, the SBT condition would help participants recognize the maladaptive thinking style producing the thought, and utilize cognitive restructuring to reduce shame and produce a more adaptive behavioral choice.) Additionally, acceptance of loss of pleasure (the ability to make the less hedonically-rewarding choice, like an apple instead of ice cream after dinner) and willingness to choose a behavior despite internal experience were emphasized while acceptance of aversive experience (e.g., the ability to accept the experience of a craving for ice cream) was deemphasized.

Treatment Fidelity

Group sessions were audio recorded and four psychologists (including EF and MLB) independently rated 25% of sessions on a scale of 1 (poor) to 10 (perfect) adherence to each section of the specific session manual. Likewise, avoidance of treatment contamination was rated from 1 (total) to 10 [9] contamination. Neither rating differed by condition (ps=.83,.79). Any adherence issues noted were immediately addressed in ongoing supervision.

Measurement

Outcomes

Weight loss (taken at each session and all assessment points) was measured with the participant in street clothes (without shoes) using a standardized Seca® scale accurate to 0.1 kg. Height was measured with a stadiometer to establish BMI (kg/m2).

Mediators (measured at baseline and mid-point)

Autonomous regulation of health behaviors was measured with the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire (TSRQ). The 15-item TSRQ has adequate reliability (α=.76–.93; current sample α=.71–.74) and predicts health behaviors such as fruit and vegetable intake, exercise, and smoking cessation [26].[26] Psychological acceptance of food cravings was measured using the 10-item Food Craving Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (FAAQ), which has adequate reliability (α=.93; current sample α=.58–77) and validity [27].

Moderators (measured at baseline)

Mood disturbance was assessed via the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), a 21-item self-report measure with excellent internal consistency and validity (current sample α=.88) [28]. Susceptibility to food cues was measured using the 15-item Power of Food Scale (PFS). The PFS has adequate reliability (α=.81–.91; current sample α=.93) and predictive validity [29, 30]. The 20-item Disinhibition subscale of the Eating Inventory (EI-D), which has good reliability (α=.91; current sample α=.79) and validity [31–33], was used to measure disinhibited eating.

Statistical Analyses

Treatment groups were compared on demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline using a chi-squared test for categorical variables and independent sample t tests for continuous measures. The primary and secondary outcomes were percent of initial body weight lost at post-treatment (12 months), and reaching ≥ 10% weight loss at post-treatment, a well-established marker of success in behavioral weight loss interventions [34]. Means and effects are reported ± standard error (not standard deviation) of the mean.

All outcome analyses were based on an intention-to-treat [23, 24] approach, and were conducted in SPSS version 23. Missing data were imputed using maximum likelihood estimation to account for the dependencies of missingness on other variables in the dataset. We repeated analyses using only data from those who completed assessments; results were equivalent, and so are not reported. Treatments were compared using a general linear mixed model, which included an autocorrelation term to account for serial dependency among within-person observations based on a first-order autoregressive component. Two time points (mid- and post-treatment) were included in the model reflecting percent of baseline weight lost. The secondary outcome was evaluated using logistic regression. Moderators were examined in separate (grand-mean centered) models via the addition of a main effect for moderator and a moderator × treatment condition interaction term. We also compared treatment groups on the trajectories of session-by-session weight, with time (i.e., week) as the independent variable, using a mixed-effects model with linear, quadratic, and cubic effects.

Hayes boostrapping simple mediation analyses (PROCESS macro for SPSS [35]) evaluated whether changes from baseline to mid-treatment in psychological acceptance and autonomous motivation mediated the effect of treatment condition on 12-month weight loss. As a check, we repeated mediation analyses using residualized change scores from baseline to mid-treatment in psychological acceptance of food-related urges and cravings; results were equivalent, and so are not reported.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The sample was 82.1% female, and primarily Caucasian (70.5%; African American: 24.7%; Asian: 1.1%; Hispanic: 3.7%) with a mean age of 51.64 ± .73 years and mean starting BMI of 36.93 ± .42 kg/m2. The groups were equivalent in in gender (χ2=.002, df=1, p=.97) and ethnicity (χ2=1.05, df=3, p=.79), and on all outcome and process measures at baseline with the exception of higher FAAQ scores in ABT (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Baseline sample characteristics

| ABT | SBT | Group differences | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | df | p |

| Age | 51.61 | 9.97 | 51.67 | 10.16 | 0.04 | 188 | .97 |

| Body mass index | 36.50 | 5.41 | 37.40 | 6.21 | 1.06 | 188 | .29 |

| BDI | 7.10 | 6.07 | 8.07 | 6.77 | 1.04 | 188 | .30 |

| PFS | 41.06 | 12.41 | 41.67 | 13.76 | 0.32 | 184 | .75 |

| EI-DIs | 8.06 | 2.50 | 8.01 | 2.52 | −0.14 | 184 | .89 |

| FAAQ | 40.23 | 7.53 | 37.97 | 6.40 | −2.20 | 184 | .03 |

| TSRQ-AM | 6.46 | 0.73 | 6.55 | 0.53 | 0.92 | 184 | .36 |

Note: BDI=Beck Depression Inventory; PFS=Power of Food Scale; EI-Dis=Eating Inventory – Disinhibition Subscale; FAAQ=Food Acceptance and Action Questionnaire; TSRQ-AM=Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire Autonomous Motivation

Table 3.

Mediator variable descriptive statistics

| Baseline | Mid-treatment | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| ABT | SBT | ABT | SBT | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | df | t | p | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| FAAQ | 40.23 | 7.53 | 37.97 | 6.40 | 184 | −2.20 | .03 | 51.03 | 9.02 | 43.70 | 6.99 |

| TSRQ-AM | 6.46 | 0.73 | 6.55 | 0.53 | 184 | 0.92 | .36 | 6.77 | .35 | 6.59 | 0.53 |

Note: TSRQ-AM=Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire Autonomous Motivation

Attendance and attrition

Treatment attendance (with inclusion of make-up sessions) was in excess of 84% of expected sessions, and there were no differences between the two treatments in terms of the average number of sessions attended (MABT=21.26 ± 5.85, MSBT=20.88 ± 5.46; t(189)=−0.46, p=.65). Overall, 84.2% of the ABT participants and 85.6% of SBT participants attended the vast majority (i.e., 18 or more) of the 25 scheduled groups (χ2=.07, df=1, p=.79). A total of 142 participants (74%) completed the mid-treatment assessment and 149 participants (78%) completed the post-treatment assessment.

Weight loss

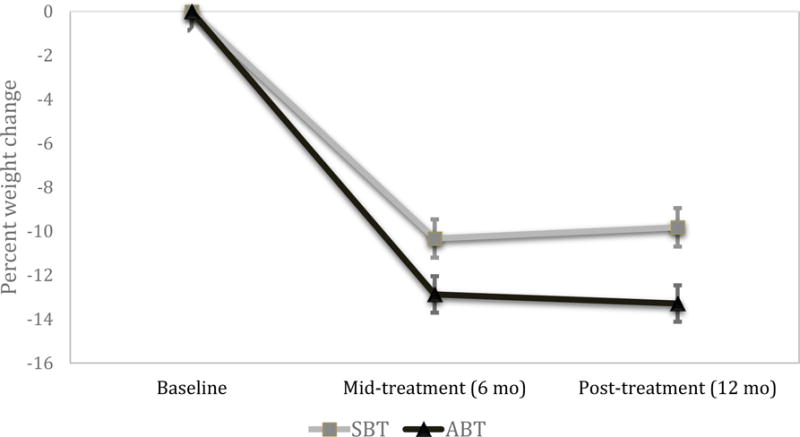

ABT yielded a significantly greater percent weight loss than did SBT across mid (MABT=12.9% ± .83, MSBT=10.3% ± .87) and post-treatment (MABT=13.3% ± .83, MSBT=9.8% ± .87; b=3.44 SE=1.21, p=.005; Figure 2). No time by treatment condition interaction was evident (b=−.92, SE=.71, p=.20). Additionally, ABT participants were more likely (64.0%) than SBT participants (48.9%) to reach 10% weight loss at 12 months (Wald χ2=4.37, df=1, p=.04, OR=1.86, 95%CI [1.04, .3.23]). Given differences in FAAQ between groups at baseline, we repeated outcome analyses with FAAQ as a covariate, and results were equivalent.

Figure 2.

Percent weight loss by treatment condition over time

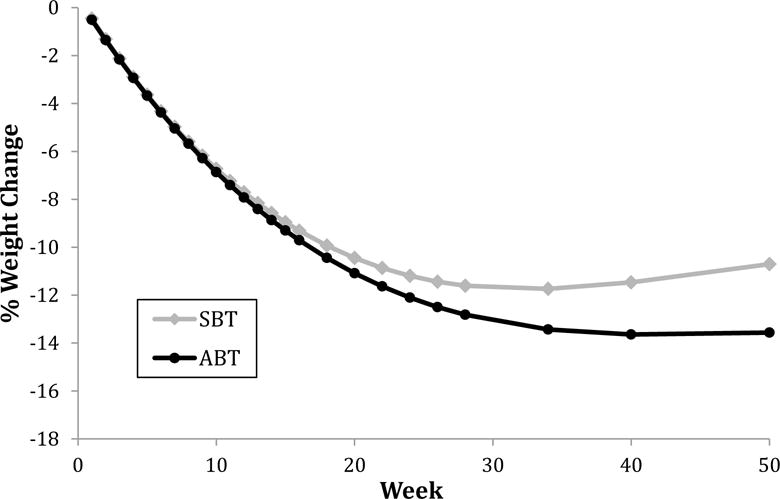

Session-by-session weight loss is depicted in Figure 3. Nonlinear analyses revealed a condition by time quadratic effect (b=0.003, SE=.001, p=.01). Specifically, SBT showed a shallower trajectory of weight loss compared to ABT with upward deflection (weight regain) by 12-months, while ABT maintained weight losses through 12 months.

Figure 3.

Session-by-session percent weight loss, with time modeled as the independent variable

Moderation

After adding a main effect for moderator and a moderator × treatment condition interaction term to the general linear model, no evidence was detected for the moderating effects of depressive symptoms (b=−.18, SE=.19, p=.28), susceptibility to food cues (b=−.02, SE=.09 p=.58), or disinhibited eating (t(215.79)=−.97, b=−.48, SE=.49 p=.69).

Mediation

The superior effect of ABT (relative to SBT) on 12-month weight loss was mediated by psychological acceptance of food-related urges and cravings (bindirect=1.55, SE=.55, 95%CI [2.65, 7.81]) and autonomous motivation (bindirect =.47, SE=.33, 95%CI [.03, 1.37]).

Discussion

During the 12-month treatment period, participants who were randomized to ABT demonstrated significantly greater weight loss than those who received SBT. In particular, SBT weight loss was 9.8%, whereas ABT weight losses were 13.3%, which represents a clinically significant 36% improvement. In addition, the likelihood of maintaining a 10% weight loss at 12 months was one-third greater for ABT, i.e., 64% vs 49% for SBT. A strength of the study is that the superiority of ABT cannot be credited to disappointing SBT results. In fact, SBT weight losses and weight loss maintenance through the reduced-contact 6-to-12-month period were better than is typically reported [36], perhaps due to differences in delivery of the intervention (e.g., continuous accountability around food records and the use of experienced Ph.D.-level clinicians). Thus, we can say with confidence that participants in ABT were able to achieve weight losses meaningfully greater than is typical with lifestyle modification [1, 4]. These findings are consistent with a large body of literature demonstrating that ABT can produce clinically significant weight losses [15, 16, 18, 20, 37, 38]. Moreover, this study, while one of the first of its kind, offers preliminary evidence that weight control outcomes can be improved by infusing behavioral treatments with skills related to acceptance of discomfort and reduced pleasure, clarification of and commitment to life values, mindful decision making.

The advantage of ABT over SBT was more pronounced in this study relative to the first Mind Your Health Trial. Several potential explanations exist for this difference including the use of experienced clinicians (who could perhaps better integrate behavioral and ABT-specific skills), and the fact that the revised ABT protocol focused more on general willingness and accepting a loss in pleasure, and less on coping with emotional distress, cravings, and hunger. These same changes to treatment focus may have been responsible for improving the efficacy of ABT treatment for all participants, such that the benefit of ABT was no longer limited to a subset of participants as it was in the previous trial [22].

This study replicated the results of the original Mind Your Health Study [22] that changes from baseline to 6 months in food-related psychological acceptance mediated the effect of condition on weight loss. Additionally, it extended this work by detecting a mediating role of autonomous motivation, which is consistent with other research demonstrating that higher amounts of autonomous motivation early in weight loss treatment are predictive of greater total weight loss [39, 40] These findings support the theory underlying acceptance-based behavioral treatment, which proposes that participants are better able to adopt and maintain changes in weight control behaviors (such as meeting a daily calorie goal) if they learn specialized self-regulation skills.

Our session-by-session analyses indicated that the advantage of ABT became increasingly evident starting about session 16 (also week 16; see Figure 3), i.e., when treatment frequency transitioned to bi-weekly (and eventually, monthly and bi-monthly). It is possible that ABT enhances skills or characteristics (e.g., autonomous motivation) that augment participants’ ability to better sustain weight control behaviors (and thus prevent weight regain) even when the frequency of group sessions lessens and external accountability diminishes. Future research should continue to investigate the ideal number of weekly sessions before transitioning to less frequent sessions.

This study has several limitations. Perhaps most importantly, assessments were not available after treatment contact ended. Generalizability is another concern given that treatment to motivated participants was delivered by expert clinicians who were trained and supervised by the treatment developers. Future studies could examine outcomes under conditions that more closely resemble typical clinical care, e.g., a community setting, with lower-intensity interventions delivered by non-psychologists. Outcomes might also have been affected by the choice of BMI ceiling, participant attrition, and variability in make-up sessions experienced. Finally, additional research must be conducted to better understand ABT mechanisms of action, for instance by using a more comprehensive battery (including behavioral measures). In conclusion, study results suggest that the efficacy of behavioral weight loss treatment can be improved by integrating self-regulation skills that are reflected in acceptance-based behavioral treatment models. Learning to tolerate discomfort or reduction in pleasure, enact commitment to valued behavior, and be mindfully aware during moments of decision making may position participants to adhere to recommendations for lifestyle modification in the face of powerful biological and environmental challenges. This is the first randomized clinical trial to demonstrate that acceptance-based behavioral treatment for obesity produced greater weight losses than the gold-standard, traditional form of behavioral treatment. Discovering ways to improve the efficacy of behavioral therapy is a key priority in the obesity treatment field; as such, the clinical and research impact of these findings is notable.

What is already known about this subject?

Behavioral treatments are the first line of weight loss interventions for obesity

Improvements can be made in the proportion of participants achieving a clinically significant weight loss, particularly over the long term

Acceptance-based behavioral treatment (ABT) is a promising alternative, but research on ABT for weight control is in its infancy

What does this study add?

This study is the largest randomized controlled trial comparing ABT to standard behavioral treatment for weight control to date

Evidence was obtained for superiority of ABT on percent weight lost at 12 months

Acknowledgments

Funding: The Mind Your Health project was funded by grant from the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (award # R01 DK095069) to Dr. Forman.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Forman reports grants from the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (award # R01 DK095069), during the conduct of the study. Dr. Crosby reports personal fees from Health Outcome Solutions, outside the submitted work. None of the remaining authors report a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Butryn ML, Webb V, Wadden TA. Behavioral treatment of obesity. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 2011;34(4):841–859. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klem ML, et al. A descriptive study of individuals successful at long-term maintenance of substantial weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66(2):239–246. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brownell KD, Jeffery R. Improving long-term weight loss: Pushing the limits of treatment. Behavior Therapy. 1987;18(4):353–374. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson G. Behavioral treatment of obesity: Thirty years and counting. Advances in Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1994;16(1):31–75. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinsier RL, et al. Do adaptive changes in metabolic rate favor weight regain in weight-reduced individuals? An examination of the set-point theory. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000;72(5):1088–1094. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.5.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowe MR. Self-Regulation of Energy Intake in the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity: Is It Feasible? Obesity research. 2003;11(S10):44S–59S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forman EM, Butryn ML. A new look at the science of weight control: How acceptance and commitment strategies can address the challenge of self-regulation. Appetite. 2015;84:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robins CJ, Ivanoff AM, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy. Handbook of personality disorders: Theory, research, and treatment. 2001:437–459. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marlatt GA, George WH. Relapse prevention: introduction and overview of the model. Br J Addict. 1984;79(3):261–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1984.tb00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forman EM, Butryn ML. Mindfulness and Acceptance Approaches to Treatment of Eating Disorders and Weight Concern, in. In: Haynos AF, Lillis J, Forman EM, Butryn ML, editors. Incorporating acceptance approaches into behavioral weight loss treatment. New Harbinger; Oakland, CA: In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forman EM, et al. A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. Behavior Modification. 2007;31(6):772–799. doi: 10.1177/0145445507302202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forman EM, et al. Comparison of acceptance-based and standard cognitive-based coping strategies for craving sweets in overweight and obese women. Eating behaviors. 2013;14(1):64–68. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hooper N, et al. Comparing thought suppression and acceptance as coping techniques for food cravings. Eat Behav. 2012;13(1):62–4. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niemeier HM, et al. An acceptance-based behavioral intervention for weight loss: a pilot study. Behav Ther. 2012;43(2):427–35. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forman EM, et al. An open trial of an acceptance-based behavioral treatment for weight loss. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2009;16:223–235. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butryn ML, et al. A pilot study of acceptance and commitment therapy for promotion of physical activity. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2009;8(4):516–522. doi: 10.1123/jpah.8.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodwin CL, et al. A pilot study examining the initial effectiveness of a brief acceptance-based behavior therapy for modifying diet and physical activity among cardiac patients. Behavior modification. 2011:119–217. doi: 10.1177/0145445511427770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lillis J, et al. Teaching acceptance and mindfulness to improve the lives of the obese: a preliminary test of a theoretical model. Annals of behavioral medicine: a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;37(1):58–69. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tapper K, et al. Exploratory randomised controlled trial of a mindfulness-based weight loss intervention for women. Appetite. 2009;52(2):396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katterman SN, et al. Efficacy of an acceptance-based behavioral intervention for weight gain prevention in young adult women. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2014;3(1):45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forman EM, et al. The mind your health project: a randomized controlled trial of an innovative behavioral treatment for obesity. Obesity. 2013;21(6):1119–1126. doi: 10.1002/oby.20169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Look AHEAD Research Group. The Look AHEAD study: a description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2006;14(5):737–752. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes care. 2002;25(12):2165–2171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levesque CS, et al. Validating the theoretical structure of the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire (TSRQ) across three different health behaviors. Health education research. 2007;22(5):691–702. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juarascio AS, et al. The development and validation of the food craving acceptance and action questionnaire (FAAQ) Eating Behaviors. 2011:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dozois DJA, Dobson KS, Ahnberg JL. A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory - II. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10(2):83–89. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cappelleri JC, et al. Evaluating the Power of Food Scale in obese subjects and a general sample of individuals: development and measurement properties. International Journal of Obesity. 2009;33(8):913–922. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowe MR, et al. The Power of Food Scale. A new measure of the psychological influence of the food environment. Appetite. 2009;53(1):114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shearin EN, et al. Construct validity of the three-factor eating questionnaire: Flexible and rigid control subscales. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16(2):187–198. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199409)16:2<187::aid-eat2260160210>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29(1):71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeomans MR, Leitch M, Mobini S. Impulsivity is associated with the disinhibition but not restraint factor from the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire. Appetite. 2008;50(2):469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jensen MD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;63(25):2985–3023. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayes AF. The PROCESS macro for SPSS and SAS. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franz MJ, et al. Weight-loss outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107(10):1755–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Butryn ML, et al. A pilot study of acceptance and commitment therapy for promotion of physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8(4):516–22. doi: 10.1123/jpah.8.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gregg JA, et al. Improving Diabetes Self-Management Through Acceptance, Mindfulness, and Values: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(2):336–343. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Webber KH, et al. Motivation and its relationship to adherence to self-monitoring and weight loss in a 16-week Internet behavioral weight loss intervention. Journal of nutrition education and behavior. 2010;42(3):161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams GC, et al. Motivational predictors of weight loss and weight-loss maintenance. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1996;70(1):115–126. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]