Abstract

Introduction

Poor dietary intake during pregnancy can have negative repercussions on the mother and fetus. This study therefore aims to explore the dietary diversity (DD) of pregnant women and its associations with pregnancy outcomes among women in Northern Ghana. The main outcome variables to be measured are gestational weight gain and birth weight.

Methods and analysis

A prospective cohort study design will be used and 600 pregnant women in their first trimester will be systematically recruited at health facilities and followed until delivery. In three follow-up visits after recruitment, information on sociodemographic and general characteristics, physical activity (International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) short form, dietary intake (24-hour food recall), anthropometry and pregnancy outcomes will be collected. DD will be measured three times using the minimum DD-women (MDD-W) indicator and the mean of the three values overall will be used to determine low (<5 food groups) and high (≥5 food groups) DD. Data will be analysed using SPSS. Comparisons between groups (categorical data) will be made using the χ2 test for proportions, and t-tests and ANOVA will be performed on continuous variables. Regression analysis will be used to identify independent outcome predictors while controlling for possible confounding factors. The results may help to identify differences in DD between healthy and unhealthy pregnancy outcomes.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol has been approved by the ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences and the ethical review committee of the Tamale Teaching Hospital. Written informed consent will be obtained from all subjects. The results will be published in due course.

Keywords: minimum dietary diversity-women, 24-hour food recall, pregnancy outcome, IPAQ-short form, Northern Ghana

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Study subjects will be easily recruited at the antenatal care units of the selected health facilities.

Some study participants may be lost to follow-up.

Random and systematic errors may occur in the dietary assessment as some pregnant women may not be able to remember all foods consumed during the recall period.

Some respondents may try to impress the researcher by mentioning foods that they have or have not consumed.

To control for the limitations mentioned above, study subjects will be introduced to the researchers and the importance of the information and study will be emphasised.

Introduction

Physiological changes in pregnant women can lead to poor dietary behaviour which may have negative repercussions on the mother and developing fetus.

Policymakers, development partners and healthcare service providers have sought to reduce maternal and infant mortality and child birth complications, both of which are major public health concerns in most developing countries.1 Adequate nutrition is essential during pregnancy as nutrition is an important factor in the health of the mother and the health, growth and development of the fetus.2–4

Weight gain is expected in pregnancy, with Mahan et al5 reporting that healthy weight gain impacts positively on pregnancy outcomes. It has also been reported elsewhere2 that suitable prenatal weight gain is associated with a lower risk of complications during pregnancy and birth. However, further research is required as data on the association between prenatal dietary patterns and birth weight are scanty and findings are inconsistent.6

The usual dietary intake of pregnant women is a key determinant of nutritional status and of nutrient depletion during pregnancy, which is a risk factor for reduced fetal growth and poor pregnancy outcome. Nevertheless, how maternal dietary diversity (DD) during pregnancy impacts on birth weight is unclear and data on the DD of pregnant women in Ghana are limited.

A number of studies in developed countries have linked DD to nutrient intake, particularly among adults. The Dietary Diversity Score (DDS) is a simple and inexpensive tool for assessing diet quality,7 and recent focus on nutritional epidemiology has shifted from examining the effect of single nutrients to assessing overall diet quality.8 Nevertheless, few studies have investigated the association between DD and pregnancy outcomes, although Saaka9 found that maternal DD was an independent predictor of birth weight in Ghana. However, his study used a cross-sectional design which has the inherent weakness of inability to measure order of exposure and subject outcome. DD has also been shown to be strongly associated with household socioeconomic status, and associations between socioeconomic status and child nutrition and health outcomes have long been recognized.9 Understanding the associations between DD and pregnancy outcomes is therefore complicated by household socioeconomic factors.

This study therefore aims investigate the role of DD in determining pregnancy outcomes among women in a low socioeconomic environment.

Objectives

The main aim of this study is to compare ?pregnancy outcomes in women with low and high DD in Northern Ghana.

The study shall also compare:

The demographic and socioeconomic characteristics (age, educational status, occupation, marital status, household size and household assets) of pregnant women in the two groups at the beginning of the study

Maternal history (parity, gravida, still birth, abortion) of pregnant women in the two groups at the beginning of the study

(iii) The physical activity level, energy and nutrient intake of the two groups at the beginning and end of the study

The weight, height, body mass index (BMI), mid upper arm circumference (MUAC),and systolic and diastolic pressure of the two groups at the beginning and end of the study

Pregnancy outcomes including gestational weight gain, birth weight, low birthweight (LBW) rate, pregnancy complications, birth complications (Apgar scores), preterm delivery and type of delivery, of the two groups at the end of the study.

Methods and design

Study design

A prospective cohort study design will be used. Study participants will be recruited during the first trimester (10–12 weeks) of their pregnancies and followed until delivery so that the incidence of outcomes and associations between exposure and outcome variables among the study participants can be measured.

Study subjects

The study subjects will be pregnant women attending an antenatal care (ANC) clinic in health facilities in Northern Ghana from the first trimester of their pregnancies.

Inclusion criteria

Pregnant women aged 20–49 years

Pregnant women in the first trimester (10–12 weeks)

Willingness of the mother to be delivered in a health facility

Willingness to participate in the study

Resident in the study area for at least 1 year.

Exclusion criteria

Women with high risk pregnancies or special needs who require specialist care or with a history of high-risk pregnancies

Women with recurrent miscarriages or treated for infertility

Women with a history of spontaneous or therapeutic abortion due to neural tube defects (NTD)

Women with known diseases (HIV, diabetes type II, renal disease, cardiovascular disease, confirmed malaria and other chronic disease) or on regular medication

Women still experiencing persistent severe nausea with vomiting by the 12th week of pregnancy

Women with an ultrasound scan results showing more than one fetus.

Sample size determination

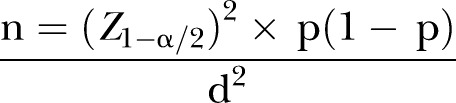

A single population proportion sample estimation formula was used to calculate the sample size for this study as follows:

|

n, Required minimum sample size; z, degree of confidence with which it is desired to be able to conclude that an observed change of size; a, margin of error (level of statistical significance); p, prevalence (proportion) of outcome variable of measure; d, precision of detecting change.

This formula was used because this is a population-based cohort study where a defined population is usually selected first, some of whose participants will be exposed (DDS) while others will not.

Main study population

Using the formula and based on an estimated prevalence of LBW of 17% (0.17) according to a study in Northern Ghana,9 an α error (level of statistical significance, 0.05) of 5%, and 18% precision) of LBW of 0.031, the estimated sample size is 579 with a 95% confidence level. To allow for 5% attrition or loss to follow-up, the final estimated sample size is 600. As we anticipate that approximately 30–40% of the 600 women will have low DDS, we will compare the outcomes of 240 women with low DDS with those of 360 women with high DDS.

Sampling

The three main hospitals (one teaching hospital and two district hospital) in the Northern Region of Ghana together with three primary health centres in Tamale, the capital of the region, will be used for recruitment and data collection. The number of subjects to be recruited from each health facility will be in proportion to the size of the centre.

A systematic random sampling technique will be used to select study participants. The first study subject will be selected randomly using a random number table, with following subjects selected according to a predetermined sampling interval until the required sample is completed.

Recruitment

Pregnant women in their first trimester (10–12 weeks) will be systematically recruited at the reproductive and child health units (where antenatal clinics are held) of the health facilities using the ANC register of the facility. The gestational age of the fetus will be determined by ultrasound in conjunction with the date the woman gives for her last menstrual period (LMP). Only those who meet the inclusion criteria will be enrolled.

Data collection

Both primary and secondary data will be gathered in this study. The general information of subjects together with predictors, outcome variables and potential confounding variables will be collected.

General information

Sociodemographic and general data will be collected using a structured questionnaire. Secondary data including maternal health history and delivery records will be obtained from Maternal Health Record Book (MHRB) and the delivery records of the study participants using a checklist.

Physical activity measurements

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-2005, short form) will be used to assess the physical activity of study subjects across different domains including leisure time and domestic, work and transport-related physical activity.10

Dietary intake assessment

A 24-hour food recall will be conducted to measure the nutrient adequacy of study subjects. Participants will be asked for a complete list of all items used in the preparation of meals. Estimates of the quantity of foods consumed will be recorded. Dietary information will be collected three times and the mean computed for nutrient estimations. The information on individual food items and portion sizes will then analysed to estimate nutrient adequacy. The 24-hour recall data will be collected with the help of a research assistant.

Minimum DD-women indicator

DD for this study will be calculated using the minimum DD-women (MDD-W) indicator which is an improved version of the Women's Dietary Diversity (WDD) score and has 10 food groups, consumption of at least 5 of which indicates high DD.11 DD will be measured three times using a 24-hour food recall and the overall mean of the three scores for all women will be used to define low and high DD.

Anthropometric measurements

At each visit participants will be weighed without shoes and with minimal or light clothing using a Seca scale. Readings will be taken to the nearest 100 g.

The height of participants will be measured only once (at recruitment) using a Seca Microtoise. Subjects will be measured to the nearest 0.1 cm while standing without shoes.

MUAC will be measured at each visit to assess wasting among study subjects using an adult MUAC non-stretchable measuring tape. The reading will be taken to the nearest 0.1 cm while the left arm relaxes along the body trunk. MUAC measurements below 23 cm will be classified as wasting and those above 23 cm as normal.12

BMI will be computed and used to assess nutritional status and the gestational weight gain of the women. Subjects with a BMI of <18.5 kg/m2, 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, 25–29.9 kg/m2 or ≥30 kg/m2 will be classified as underweight, normal, overweight or obese, respectively.13 The Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommended guidelines14 will be used to estimate gestational weight gain. Women who are underweight, normal, overweight and obese are expected to gain 12.7–18.2 kg, 11.4–15.9 kg, 6.8–11.4 kg and 5–9.1 kg gestational weight, respectively, before delivery.

Blood pressure measurements

Blood pressure of subjects will be measured to the nearest 0.5 mm Hg using a digital arm sphygmomanometer after a 10 min rest while in a supine position. Measurements will be performed at each visit.

Measurement of pregnancy outcomes

Pregnancy outcome records will be obtained from physician's notes on the MHRB after delivery and/or the woman herself using a simple checklist.

Follow-up

There will be three follow-up visits after recruitment. Two (at 22–24 weeks and 36–37 weeks of gestation) will be during the pregnancy and the third after delivery. Sociodemographic and general information will be collected at recruitment. Dietary intake and physical activity will be measured at recruitment and the first two follow-up visits (at 22–24 and 36–37 weeks). Weight, MUAC, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure will be measured at recruitment and at each visit, while height will only be measured once at recruitment.

Variable and potential confounders

The primary outcomes variables that will be measured in this study are pregnancy weight gain before delivery and birth weight. The secondary outcomes variables will include pregnancy complications (pre-eclampsia), birth complications (asphyxia/Apgar scores), preterm delivery and type of delivery. DDS and amount of nutrient intake will be measured as the anticipated predictor variables of the primary and secondary outcome variables. The potential confounding variables that will be measured include age, educational status, marital status, occupation, household size, socioeconomic status (household wealth index), maternal history (eg, parity, G6PD status, still birth, abortion and gravida), smoking, alcohol intake, pica, dietary supplementation, craving for certain foods, cultural practices, BMI and physical activity.

Data analysis

Data will be cleaned, entered into a computer database and analysed using SPSS V.22 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Univariate, bivariate and multivariate analyses will be performed on the variables and 95% confidence levels will be set to test for significance. The data will first be analysed using descriptive statistics. Frequency tables will be produced for different variables and cross tabulations will be performed accordingly. Comparison between groups (categorical data) will be done using χ2 tests for proportions, and t-tests and ANOVA will be used on continuous variables. Regression analysis will be performed to identify independent outcome predictors while controlling for possible confounding factors. Relative risks at 96% CI will be computed to ascertain the presence and degree of association between independent and dependent variables.

The nutritional intake of each food item will be converted into g/day. Information from the 24-hour food recall will be converted into quantities (quantitative data) of nutrient intakes using Ghana's food composition table and food processor software. The recommended nutrient intake (RNI) will be used to assess the nutrient adequacy of diets.

Ethical issues and informed consent process

The study protocol has received approval from the ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.REC.1394.495) and Tamale Teaching Hospital (TTH/10/11/15/01). The investigators will provide study subjects with all the information they need to participate in the study through an informed consent form, which will be read to those not able to read in English by the interviewer in the presence of a witness. The consent form will be signed or marked with the thumb print of the subject and signed by the interviewer and investigator. Only those who give their consent will be included in the study.

Discussion

Maternal diet during pregnancy may influence pregnancy and childhood outcomes, such as length of gestation, fetal growth, birth defects, pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes and the offspring's cognitive development, blood pressure, adiposity and atopic disease.15–25 Bodnar and Siega-Riz26 observed that diet quality can be measured by assessing dietary intake and determining whether it reflects the recommendations for pregnancy established by the United States Department of Agriculture and the IOM. An increase in DD has therefore been advocated as a way to improve micronutrient status in populations because it offers some benefits not provided by supplements during pregnancy.27 28 The available literature29–31 suggests that diet quality before and during pregnancy can affect pregnancy outcome. An observational study in India showed that rural mothers who consumed foods rich in micronutrients (green leafy vegetables, fruit, and milk) gave birth to infants who were heavier and larger than the children of mothers who did not.32 Other studies suggested that diet quality in pregnant women should be examined.33 34

The results of the literature search revealed that little is known about DD and pregnancy outcomes, particularly in low socioeconomic environments.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Kudaani, Vice Dean of Research of the School of Nutritional Sciences and Dietetics, for helping to design the study and obtain approval for the study protocol.

Footnotes

Contributors: SMO, GS, MS, and PY conceived and designed the study. SMO was involved in drafting the manuscript. GS critically revised the manuscript and approved the final submitted version. MS and FS revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. MQ and ID made substantial contributions to statistical design. PY edited the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the International Campus of Tehran University of Medical Sciences under grant number 9323475001.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences and the Ethical Review Committee of Tamale Teaching Hospital approved this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Findings will be submitted as a PhD thesis and as manuscripts for publication. Data will be shared only with those involved in the study.

References

- 1.Zakaria H, Laribick DB. Socio-economic determinants of dietary diversity among women of child bearing ages in northern Ghana. Food Sci Qual Manag 2014;34(2014):12–25. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser L, Allen LH, American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: nutrition and lifestyle for a healthy pregnancy outcome. J Am Diet Assoc 2008;108:553–61. 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blumfield ML, Hure AJ, Macdonald-Wicks L et al. . Micronutrient intakes during pregnancy in developed countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev 2012;71:118–32. 10.1111/nure.12003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenseke B, Prater MR, Bahamonde J et al. . Current thoughts on maternal nutrition and fetal programming of the metabolic syndrome. J Pregnancy 2013;(2013):1–13. 10.1155/2013/368461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahan LK, Escott-Stump S, Raymond JL. Krause's food and the nutrition care process. 13th edn. USA: Elsevier, 2012:342–64. ISBN:978-1-4377-2233-8 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sánchez-Villegas A, Brito N, Doreste-Alonso J et al. . Methodological aspects of the study of dietary patterns during pregnancy and maternal and infant health outcomes. A systematic review. Matern Child Nutr 2010;6:100–11. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2010.00263.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.FAO. Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity. Rome, Italy, 2013. ISBN:978-92-5-106749-9 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poon AK, Yeung E, Boghossian N et al. . Maternal dietary patterns during third trimester in association with birthweight characteristics and early infant growth. Scientifica (Cairo) 2013;2013:786409 10.1155/2013/786409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saaka M. Maternal dietary diversity and infant outcome of pregnant women in Northern Ghana. Int J Child Health Nutr 2012;1:148–56. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M et al. . International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:1381–95. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.FAO/FANTA. Introducing the minimum dietary diversity—women (MDD-W) global dietary diversity indicator for women. Washington, DC, 15–16 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Food Programme. Emergency food security assessment handbook. 2nd edn. Rome, Italy: UN/WFP, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organization Tech Rep Ser. 854 Geneva: WHO, 1995:1–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Institute of Medicine (IOM). Nutrition during pregnancy. Washington DC: National Academies Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute of Medicine (IOM). Nutrition during pregnancy. Washington DC: National Academies Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olsen SF, Sørensen JD, Secher NJ et al. . Randomised controlled trial of effect of fish-oil supplementation on pregnancy duration. Lancet 1992;339:1003–7. 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90533-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobson SW, Jacobson JL, Sokol RJ et al. . Prenatal alcohol exposure and infant information processing ability. Child Dev 1993;64:1706–21. 10.2307/1131464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dietz WH. Critical periods in childhood for the development of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 1994;59:955–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldenberg RL, Tamura T, Neggers Y et al. . The effect of zinc supplementation on pregnancy outcome. JAMA 1995;274:463–8. 10.1001/jama.1995.03530060037030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurley L, Swenerton H. Congenital malformations resulting from zinc deficiency in rats. Proc Soc Exper Biol Med 1996;123:692–6. 10.3181/00379727-123-31578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Cook RJ et al. . Effect of calcium supplementation on pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 1996;275:1113–17. 10.1001/jama.1996.03530380055031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grandjean P, Weihe P, White RF et al. . Cognitive deficit in 7-year-old children with prenatal exposure to methylmercury. Neurotoxicol Teratol 1997;19:417–28. 10.1016/S0892-0362(97)00097-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Botto LD, Moore CA, Khoury MJ et al. . Neural-tube defects. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1509–19. 10.1056/NEJM199911113412006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barker DJ, Eriksson JG, Forsén T et al. . Fetal origins of adult disease: strength of effects and biological basis. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:1235–9. 10.1093/ije/31.6.1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mihrshahi S, Peat JK, Marks GB et al. . Childhood Asthma Prevention Study. Eighteen-month outcomes of house dust mite avoidance and dietary fatty acid modification in the Childhood Asthma Prevention Study (CAPS). J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;111:162–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bodnar L, Siega-Riz A. A Diet Quality Index for Pregnancy detects variation in diet and differences by sociodemographic factors. Pub Health Nutr 2002;5:801–9. 10.1079/PHN2002348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nantel G, Tontisirin K. Policy and sustainability issues. J Nutr 2002;132(Suppl 4):839S–44S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibson RS. Strategies for preventing multi-micronutrient deficiencies: a review of experiences with food based approaches in developing countries. In: Thompson B, Amoroso L, eds. Combating micronutrient deficiencies: food-based approaches. Wallingford, UK: CAB International; Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2011:7–27. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith GC. First trimester origins of fetal growth impairment. Semin Perinatol 2004;28:41–50. 10.1053/j.semperi.2003.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brodsky D, Christou H. Current concepts in intrauterine growth restriction. J Intensive Care Med 2004;19:307–19. 10.1177/0885066604269663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King JC, Cousins RJ, Zinc. In: Shils ME, Shike M, Ross AC et al.. eds Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 10th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2006;271–85. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao S, Yajnik CS, Kanade A et al. . Intake of micronutrient-rich foods in rural Indian mothers is associated with the size of their babies at birth: the Pune Maternal Nutrition Study. J Nutr 2001;131:1217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Messina M, Lampe JW, Birt DF et al. . Reductionism and the narrowing nutrition perspective: time for reevaluation and emphasis on food synergy. J Am Diet Assoc 2001;101:1416–9. 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00342-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watts V, Rockett H, Baer H et al. . Assessing diet quality in a population of low-income pregnant women: a comparison between Native Americans and whites. Maternal Child Health J 2007;11:127–36. 10.1007/s10995-006-0155-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]