Abstract

Objectives

To explore how a medical textbook app (‘iDoc’) supports newly qualified doctors in providing high-quality patient care.

Design

The iDoc project, funded by the Wales Deanery, provides new doctors with an app which gives access to key medical textbooks. Participants’ submitted case reports describing self-reported accounts of specific instances of app use. The size of the data set enabled analysis of a subsample of ‘complex’ case reports. Of the 568 case reports submitted by Foundation Year 1s (F1s)/Year 2s (F2s), 142 (25%) detailed instances of diagnostic decision-making and were identified as ‘complex’. We analysed these data against the Quality Improvement (QI) Framework using thematic content analysis.

Setting

Clinical settings across Wales, UK.

Participants

Newly qualified doctors (2012–2014; n=114), F1 and F2.

Interventions

The iDoc app, powered by Dr Companion software, provided newly qualified doctors in Wales with a selection of key medical textbooks via individuals’ personal smartphone.

Results

Doctors’ use of the iDoc app supported 5 of the 6 QI elements: efficiency, timeliness, effectiveness, safety and patient-centredness. None of the case reports were coded to the equity element. Efficiency was the element which attracted the highest number of case report references. We propose that the QI Framework should be expanding to include ‘learning’ as a 7th element.

Conclusions

Access to key medical textbooks via an app provides trusted and valuable support to newly qualified doctors during a period of transition. On the basis of these doctors’ self-reported accounts, our evidence indicates that the use of the app enhances efficiency, effectiveness and timeliness of patient-care in addition consolidating a safe, patient-centred approach. We propose that there is scope to extend the QI Framework by incorporating ‘learning’ as a 7th element in recognition of the relationship between providing high-quality care through educational engagement.

Keywords: technology enhanced learning, quality improvement framework, newly-qualified doctors, smartphones, workplace learning, physicians

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The size of data set enabled analysis of subsample of ‘complex’ case reports.

Novel analysis of data against a well-used Quality Improvement (QI) Framework which facilitates comparison with other QI studies.

Multisites, across Wales.

Not all newly qualified doctors participated.

We did not gather participant feedback regarding findings from this analysis.

Background

The health service and those who work within it face challenges from fiscal budgets, demographic changes which increase the complexity of patient care and an explosion of information about different treatments and care pathways. Notwithstanding these demands, alongside enhanced efficiency, the health service is expected to improve the quality of patient care. The Institute of Medicine's1 Quality Improvement (QI) Framework defines high-quality healthcare as that which is safe, effective, efficient, timely, patient-centred and equitable. Yet, the evidence is clear that healthcare is not always good and can lead to poor patient experience and outcomes.2 Levels of harm have been reported as equivalent to 1 in 48 consultations.3

One established contributory risk factor is the transition period in August when newly qualified doctors start work, a period renowned for higher patient death rates as more experienced doctors move to different departments.4–6 Dubbed by the UK press as the ‘killing season’ or ‘black Wednesday’, the support needs of new doctors is a widely recognised, pressing issue. This paper focuses on one strategy—a mobile app—which has been used to assist junior doctors. This smartphone app provides immediate electronic access to books which allow the user to access accurate information in the workplace. While studies have explored how smartphones can improve communication within education and training, there is a paucity of literature considering how smartphones are used within hospital settings as a point of reference.7 8 The main emphasis in research to date has been on attitudes and perspectives on the potential benefits and challenges of smartphone use.9–11 Knowledge about how mobile technology is actually used by newly qualified doctors in practice is sparse. Concern about doctors using unregulated apps containing out-of- date content has been recognised as challenge with implications for patient safety.12 13 Our study provides a significant contribution to the field by looking at how access to key medical texts can directly benefit newly qualified doctors' professional and personal development as well as support patient care priorities. In this paper, we take the novel approach of using the QI Framework to explore how having access to a mobile library of medical textbooks on an app supports the quality of patient care.

Methods

The intervention

From 2012, newly qualified doctors in Wales were offered access to an app that could be downloaded on to their own personal smartphone.14 The iDoc app, powered by Dr Companion© software, provides internet-free access to a library of cross-searchable medical texts used routinely in hospital departments in the UK. They are updated regularly and pushed to the app within days of national release when users enter a wi-fi zone, thereby avoiding the dangerous pitfalls encountered by doctors using apps that house unregulated or out-of-date content. Data reported here were collected from a 24-month period from August 2012. Medical texts available on the iDoc app were: the British National Formulary (BNF), the BNF for Children, the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine, the Oxford Handbook of Emergency Medicine, the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialities and the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Surgery.

The iDoc project participants are newly qualified doctors on the UK Foundation Training Programme which bridges the gap between medical school and specialist training. The number of Foundation Year 1 (F1) trainee doctors in Wales in 2012/2013 was 322, increasing to 374 in 2013/2014. On entry to F1, all new trainee doctors received an email invitation to take part in the iDoc project. Participation was voluntary and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. In order to access the resource, participants were required to complete a baseline questionnaire, and encouraged to submit two case reports (see below). However, the resource remained active even if participants failed to comply with requests for case reports. Research ethics approval for the iDoc evaluation was obtained from Cardiff University (2 December 2010).

Case reports

Case reports were electronic forms completed by participants describing specific events or times when they used the iDoc app. Participants were sent an email with a hyperlink to the online form held on Bristol Online Survey (BOS) software. The structured case report asked respondents to complete sections describing the setting or context, problem or issue addressed, what happened, books that were useful, what would have happened if they had no access to iDoc, any obstacles to use, and reflections. All sections were optional. Case reports were confidential but not anonymous.

Data analysis

Exported data from BOS were imported into Nvivo-10, a qualitative data analysis computer software package. In total, 295 case reports were submitted in the period August 2012–July 2013 by F1s and F2s (cohort C2012/2013) and 273 the following 12-month period (cohort C2013/2014). Case reports were classified as ‘simple’ or ‘complex’ and the complex case reports were subjected to thematic analysis using an adapted Framework approach.15 This entailed using a coding frame based on a priori themes derived from the QI Framework (table 1), and were further supplemented by emergent themes identified through discussion within the research team. The classification of case reports into ‘simple’ and ‘complex’ and the subsequent coding of the complex case reports was undertaken by KW and AB and disagreement discussed with the medically qualified member of the team (MS). KW and AB have substantial experience in qualitative research and analysis.

Table 1.

| Safe | Timely |

|---|---|

| Avoiding harm to staff and patients from care that is intended to help them | Reducing waits and sometimes harmful delays |

| Effective | Efficient |

| Providing services based on evidence and which produce a clear benefit | Avoiding waste |

| Person-centred | Equitable |

| Establishing a partnership between practitioners and patients to ensure care respects patients' needs and preferences | Providing care that does not vary in quality because of a person's characteristics |

Results

In total, 568 case reports were submitted by 269 F1/F2s. Of these, 142 (25%) were ‘complex’ case reports submitted by 114 different F1/F2s. The remaining 426 (75%) case reports, submitted by 242 different F1/F2s, were classified as ‘simple’.

These ‘simple’ cases represented diverse use of the iDoc app and included routine checks of which drugs or dosage to use, treatment or management information and general learning or revision. Simple dosages checks were frequent. An example of a simple of drugs check is a trainee reporting: ‘I used the app to look up alcohol withdrawal finding out which drug was recommended to help settle the patient’ (C2013/2014). A treatment or management information example is a trainee reporting: “I remembered the mnemonic but could not remember all the relevant parts of it. I used the iDoc app to assist me with gaps in my knowledge. This enabled me to score the patient appropriately and allowed me to remind myself of the management based on the different scoring system” (C2013/2014). Trainees also reported simple use of the app to further knowledge: “The app … allows me to revise and learn when out and not at work.… It is helping me to continue improving my knowledge base” (C2012/2013).

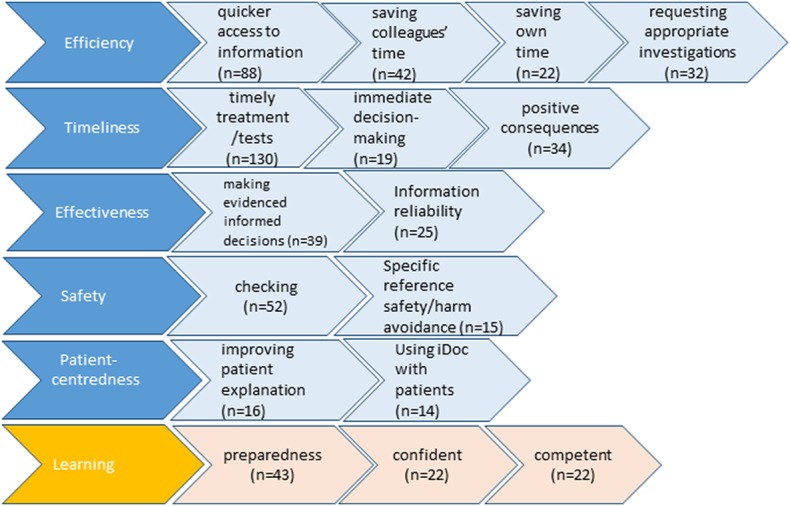

The ‘complex’ case reports detailed instances where iDoc was used in diagnostic decision-making. Although sometimes, including simple checks, these cases were not limited to such checks. We begin by presenting an overview of the themes and associated subthemes and the number of passages receiving a code under each of these (figure 1). Ninety-eight per cent (n=139) of ‘complex’ case reports attracted a theme related to ‘efficiency’. Of these, a total of 184 passages of text were coded to ‘efficiency’. Comparatively fewer passages were coded to ‘safety’ (n=67), ‘timeliness’ (n=66), ‘effectiveness’ (n=64) or ‘patient-centredness’ (n=30) across case reports. We added a new theme, ‘learning’, to the QI Framework and this was coded 87 times. We note that none of the case reports were coded to the ‘equitable’ theme.

Figure 1.

Overview of results.

Efficiency

Within the QI Framework, ‘efficient’ is defined as ‘avoiding waste, of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy’.1 The four subthemes (quicker access to information, saving own time and colleague's time and requesting investigations) that were included under ‘efficient’ mainly concerned avoiding wasted energy, for example, by providing information faster than PCs or hard copy books.

Quicker access to information (n=88)

iDoc was reported to provide speedy access to information: “it is always there on my phone with just a click away” (C2012/2013:3.14). This was juxtaposed against other information sources in the workplace which were found to be slower or unavailable. Participants frequently stated that medical textbooks were difficult to locate, access or were unavailable.

Whilst the hospital library may have a copy of the latest Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine, this would be extremely difficult to access during a ‘normal’ clinical day let alone an out-of-hours shift. (C2012/2013:3.15)

Nurses went to find a BNF…slower than the app. (C2013/2014:4.33)

The iDoc app was also favoured over PCs and the internet. Participants experienced difficulties obtaining information via PCs or the internet: ‘obtaining information from good medical websites is notoriously difficult as the trust has blocked access to nearly all of them’ (C2012/2013:3.20). Issues around intranet systems not working, internet speeds, as well as limited or no wi-fi access were also cited:

3G reception in the [hospital name] mostly requires you hanging out of a window to get a single bar. (C2012/2013:3.60)

Physical access to PCs was also an issue. Trainees needed both to know where to find a PC and for it to be available at the time of need.

Saving own time and colleagues' time (n=64)

Coded under the theme of ‘efficient’ were descriptions of iDoc saving trainees' ‘own’ time (n=22) by facilitating swifter movement onto the next case or job. For instance:

It enabled my clerking to be performed in a more timely fashion to a high standard enabling me to move onto other patients quickly during this time pressure shift. (C2012/2013:3.21)

We also coded reference to the use of iDoc saving the time of colleagues (n=42). Participants described how iDoc gave them confidence not to disturb colleagues unnecessarily or too early:

I don't think it would have been very appropriate to involve a senior … but if I didn't have the app and had no other source of information the only other option would have been to ask for senior advice. (C2013/2014:4.46)

In addition, efficient access to information served to maximise the time of the medical team to the benefit of trainees: “the team would have had to delay the ward round in order to use textbooks to base our management upon, and as juniors, we may have had to miss several patients on the ward round to collect information for our seniors from several sources” (C2012/2013:3.61).

Participants frequently cited information from iDoc as facilitating communication with seniors. For example, one described how it “enabled me to speak confidently with the on-call Cardiologist, referencing evidence-based guidelines to support my decision to seek support” (C2012/2013:3.1). Having the information to hand helped prime newly qualified doctors for conversation with others and could provide reassurance to senior colleagues on management decisions:

I explained that I had checked the scoring system on my phone using the iDoc app. They were reassured by this. (C2012/2013:3.14)

This made the specialist more confident in my assessment. (C2013/2014:4.32)

Requesting appropriate investigations (n=32)

Avoiding waste from inappropriate investigations was another way in which iDoc aided efficiency:

We were not requesting irrelevant tests or receiving too many confusing or conflicting test results all at the same time. (C2012/2013:3.61)

It's saved the patient unnecessary examinations and a lot of coming and going in a busy unit. (C2012/2013:3.25)

Timeliness

The framework describes ‘timely’ as reducing waits and harmful delays for those who receive and those who give care.1 Three subthemes included under this theme are timely treatment/tests, immediate decision-making and positive consequences.

Timely treatments/tests (n=13)

Participants frequently spoke of information retrieval facilitating a timely intervention:

I needed the information so that I could clerk the patient and have them suitably treated in a timely fashion. (C2012/2013:3.50)

Delays “in patient care and management” (C2012/2013:3.26) were noted to have been avoided by access to timely information.

Immediate decision-making (n=19)

Having iDoc and the ability to ascertain information at point-of-care was described as facilitating immediate decision-making: for example, it helped to “make a quick decision on whether or not to send her for a compression ultrasound” (C2013/2014:4.15).

Some included positive references to the use of iDoc in emergency or acute situations, where information was required in an instant:

I needed to ascertain if I needed help immediately or if I could wait until my SHO [senior house officer] and registrar finished in theatre. (C2012/2013:3.14)

Information on-the-spot aided emergency treatment:

This helped to speedily treat the patient for their condition and effectively prevent a catastrophe. (C2012/2013:3.66)

iDoc was quick to use and easily accessible in the emergency situation giving the information required in an easy manner. (C2013/2014:4.53)

Positive consequences (n=34)

Within descriptions about timely access to information, there were references to this having the effect of alleviating patient distress:

I was able to find the information straight away. It meant the patient could receive the right treatment in a timely fashion, alleviating their distress. (C2012/2013:3.54)

The patient therefore got a more thorough assessment and were disturbed for less time (it was 2am) than she would have done if I wasn't sure about the things I wanted to exclude. (C2013/2014:4.52)

Specific delays to treatment had iDoc not been available were also mentioned:

If I did not have the iDoc app it would have taken me longer to research differential diagnosis and therefore prolong time to the correct treatment. (C2012/2013:3.64)

This would have necessitated that I leave the ward and delayed ordering of serum samples which would ultimately affect patient care. (C2013/2014:4.7)

There were 28 specific references to reduced delays, with notable impact on patient care:

I probably would have advised the nurse to withhold the medication until the morning, which although sensibly cautious, may have had an adverse reaction on the patient. (C2013/2014:4.55)

Effectiveness

In the QI Framework, ‘effective’ describes care based on robust evidence.1 This theme included two subthemes: making evidenced informed decisions and information reliability.

Making evidenced informed decisions (n=39)

Although all case reports in this analysis were deemed complex, they nonetheless sometimes included simple checking as part of the report. Thus, we coded under this theme where the app was used for checking dosages or correct treatments, “effectively use it as a checklist to ensure I had carried out all the necessary investigations and initiated the necessary treatment” (C2012/2013:3.6), reminding themselves of knowledge they had learnt but could not bring to mind—“in order to refresh my knowledge of this subject area an ensure that I have not missed any key factors” (C2012/2013:3.1), or checking their clinical judgement was appropriate, “to ensure I had the correct management in place” (C2013/2014:4.3).

In this theme, we also coded occasions where participants used iDoc to systematically think through diagnosis, events or procedures: “Myself and the registrar were confused about the situation and it [iDoc] helped us to clarify our thoughts and work systematically” (C2012/2013:3.42). In difficult cases, iDoc was said to afford the newly qualified doctor a wider perspective on rare presentations:

I used the app to correctly identify that a patient was demonstrating symptoms consistent with Churg Strauss. The rare and complicated disorder can have many subtle symptoms and this app proved invaluable at the time in providing this information. (C2012/2013:3.30)

Knowledge accessed via the iDoc app was reported to influence decision-making. The following extract describes how the information led to a change in the patient's course of treatment:

I used information to quickly recap on Carcinoid syndrome and carcinoid crisis. This led to the consultant using a journal search to find guidelines of management of carcinoid syndrome and anaesthesia and the risks.…We also identified heart valve problems in carcinoid syndrome and a quick auscultation of the patient's heart identified murmurs (although we were unsure exactly what at the time). The patient's surgery was cancelled until an ECHO was performed. (C2013/2014:4.27)

Information reliability (n=25)

Participants referred to the reliability of information provided within the app: “I knew by using iDoc I would be getting accurate information” (C2013/2014:4.2).

Safety

Safety is described within the QI Framework as avoiding harm to staff and patients from care that is intended to help them.1 We coded two subthemes: checking and specific reference to safety/harm avoidance.

Checking (n=52)

Although our focus was on more complex case reports, as a component of those, reference was also sometimes made to simple checking. Within our sample of submitted case reports, participants described instances where the use of the iDoc app supported harm avoidance for patients through checking:

It allowed me to quickly search for bradycardia to determine causes I may not think of but more importantly for the use of the BNF for the exact dose of atropine. (C2012/2013:3.67)

Ready access to information in-the-moment provided harm avoidance for new doctors in stressful situations where critical information retrieval was at risk of being impaired:

This was my first on-call shift and faced with a patient who looked so unwell, I struggled to organize my thoughts and tried to remember all the necessary investigations that needed to be carried out. I used the iDoc application…to ensure I hadn't missed anything out before calling my senior. (C2012/2013:3.6)

Specific reference to safety/patient harm avoidance (n=15)

Participants made specific reference to safety and patient harm. These were in terms of how retrieval of information could avoid harm to patients and support live-saving decisions:

He was being treated with Prednisolone, so it was important to stop this and I knew (from what I read in the app) that would exacerbate the diverticulitis. I switched his antibiotic to cefuroxime and metronidazole IV. Also I used the BNF to find the doses of antimuscarinics to help the patient with the spasms he was suffering and the analgesia I was not familiar prescribing. (C2012/2013:3.68)

I accessed the BNF via the app which described that in these cases, a short acting small dose of a benzodiazepine medication is appropriate—other types were likely to precipitate a coma in this patient! (C2013/14:4.17)

Patient-centredness

In the QI Framework, patient-centred care is respectful of and responsive to individual patient values through, for example, involving patients in decision-making.1 Subthemes identified included improving patient explanation and using iDoc with patients.

Improving patient explanation (n=16)

iDoc facilitated a patient-centred approach by supporting explanations to patients: “this positively impacted patient treatment as I was able to explain to child's parents what had caused the rash” (C2012/2013:3.26). Trainees reported feeling better able to answer patient queries and provide more information on investigations and next steps:

I was able to answer the patient's questions regarding the disease process and required investigations to rule out underlying malignancy. (C2012/2013:3.4)

Patient was reassured that I was able to give her accurate information from a known medical book. … My patient felt reassurance and was grateful since she felt I had given her more information than she had received from previous doctors. (C2013/2014:4.22)

Using iDoc with patients (n=14)

Occasionally, iDoc was used to involve patients in decision-making. By being better informed, doctors and patients were better able to make a collaborative decision:

Improved the information I was able to give to the patient for us to make an informed decision with the consultant, during the post take ward round […] the patient wouldn't have received such detail information and wouldn't have felt as involved in the decision making as a consequence. (C2013/2014:4.11)

Learning

This theme looks at the learning aspect of using iDoc and is in addition to the existing six elements of the QI Framework. This theme includes practical aspects of learning and also emotional references associated with learning, for example, feeling happier, being more confident. We identified three subthemes: confident, competent and preparedness.

Preparedness (n=43)

Case reports included references to being prepared for practice. For instance, access to the app aided doctors' preparedness for management of critical events intellectually and emotionally:

When I got to the ward the nurses and I managed to calm and reorientate the patient by talking to him. However, the additional knowledge prepared me for a worsening of the situation and gave me confidence. (C2013/2014:4.58)

The newly qualified doctors also reported that consulting the app resulted in sustained knowledge. For example, one commented ‘I will not forget this information as it was useful to cross reference sources so easily’ (C2013/2014:4.55).

Confident (n=22)

The acquisition and learning of information through the use of the app was associated with reference to ‘being’ or ‘feeling’ confident. The app provided a scaffold which supported trainee doctors' learning: “now this information is something I have learned and now feel more confident in dealing with paracetamol overdoses” (C2013/2014:4.36).

Competent (n=22)

Others made reference to their competence, “This meant that I could manage the patient far more competently overnight and could explain the procedure to the patient, placing her at ease” (C2013/2014:4.3). The use of iDoc helped to solidify learning, reinforcing knowledge and linking experience:

I am less likely to forget this as I had to look it up, whereas if I had asked a colleague I may have been likely to forget it at a later date. (C2013/2014:4.25)

Discussion

These case reports provide valuable insight to what the newly qualified doctors in our sample experienced within the first 2 years as a practising physician and how, at the time of an event, access to the app provided by the Wales Deanery supported them in making decisions about patient care. Within this paper, we have focused our attention on case reports which described more complex scenarios. Specific focus on complex case reports provide greater understanding of how and in what ways iDoc, as a mobile application, provides support to newly qualified doctors during critical periods where other options were unavailable. Although we recognise that simple checking using the iDoc app, particularly around dosages, remains a critically important component of safe patient care, our focus on complex scenarios has enabled us to document and classify the diverse ways in which the smartphone apps seems to contribute to the quality of care provide by new doctors.

A limitation of our study is that we did not collect comparative data from trainees who did not have the app. This limitation is ameliorated by data from a question on the case report proforma that asked ‘what would you have done had you not had the app’. Responses included searching for a hard copy textbook (which may not be the latest edition), waiting for a member of staff to become available, trying to find an unoccupied ward computer and access the internet to ‘Google it’. These data provide some insight into what non-users might be doing. The use of iDoc prevents the risk of doctors' needing to access potentially unregulated medical content.

Another limitation of our data is recall bias; we do not know the time interval between the experience as presented by the newly qualified doctors and the submission of their case report. Furthermore, these accounts are newly qualified doctors' perceptions of how using the app improves care quality rather than observed practice. However, these accounts were salient to these doctors and as such are worthy of consideration. Of all those submitting case reports, six trainees provided examples of obstacles to using the app these included using the app in front of patients, not having localised guidelines and the BNF being initially difficult to navigate. Improving quality of healthcare is a continual challenge and methods by which QI can be implemented are varied.16 The QI Framework is an attempt to identify criteria which can focus attention on what to improve and measure.17 Here, we have sought to demonstrate the value of the iDoc by analysing case reports against the QI Framework. By applying these six elements to newly qualified doctors' descriptions of using the app in the workplace, we reveal how its function extends beyond simple information retrieval to enhance patient experience and outcomes. Using the app, often during a critical event, evidences five of the six dimensions of high-quality care: safe, timely, effective, efficient and patient-centred.

Evidence from this case report analysis led to our proposal to extend the QI Framework by including ‘learning’ as a seventh element. This recognises the relationship between educational engagement and high-quality care. The importance of continued learning, through access to ready information, helps consolidate knowledge by making concrete links between on-the-job medical experience and scientific underpinnings of practise. This supports the value that the General Medical Council's puts on education and training for postgraduate trainees.18

At a time of intense fiscal pressure, a central purpose of QI is to maximise health service outcomes. The Health Foundation draw on the definition proffered by Øvretveit19 that QI is a process designed to achieve better outcomes through the combination of a ‘change’ (improvement) and a ‘method’ (an approach with appropriate tools) where particular attention is paid to context.3 Our findings fit with the purposes of QI. App usage, for instance, had the effect of maximising the time of medical teams and increasing productive communication for the benefit of trainees, senior colleagues and patients. The absence of such a mobile information resource could result in wasted time, of the trainee and the senior colleagues, as well as an increased risk of negative outcomes for patients.

Our analysis provides examples of how the use of iDoc within the workplace directly supports domains within the NHS outcomes framework 2015/2016. Domains 4 (ensuring that people have a positive experience of care) and 5 (treating and caring for people in a safe environment and protecting them from avoidable harm) are particularly relevant.20

The last 20 years has seen an important shift to evidence-based medicine (EBM).21 Sackett et al22 described EBM as a combination of clinical judgement, patient values and preference, and relevant scientific evidence. The iDoc app supports EBM by providing ready access to credible and BMA-endorsed key medical texts, and our data demonstrate how trainees use this to support their clinical judgements. Patient values and preferences align with patient-centeredness in the QI Framework and we have demonstrated that iDoc app usage support this.

EBM is not without its critics. Concerns of reliance on experimental findings undermining clinical knowledge acquired through experience have been raised, along with whether such averaged findings could realistically inform decisions about real patients.23 Greenhalgh et al point to the huge amount of evidence and challenge the effectiveness of evidence-based management in a landscape of increasingly complex patient needs.24 25 They suggest a refocussing of EBM towards what they coin as ‘real’ EBM, where care is patient-centred and evidence is subjected to clinical judgement and better understood in relation to patient needs and context.24 We argue that the iDoc app fits with the QI Framework and real EBM. Put simply, evidence-based care is supported through immediate access to regularly updated key medical textbooks which supports trainees' decision-making and engagement with colleagues and facilitates patient involvement.

Conclusion

On the basis of doctors' self-reported accounts of more complex cases which we have analysed against the QI Framework, we have shown that the iDoc app supports QI in healthcare services in multiple ways. We have evidenced how the app enhances the safety, efficiency, effectiveness and timeliness of patient care, and how some doctors also using it to consolidate their patient-centred approach. We propose that there is scope for the QI Framework to incorporate a seventh element, ‘learning’, which would give recognition to high-quality care being characterised by practitioners engaged in ongoing learning.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Wales Deanery in commissioning and funding this evaluation of the iDoc project. Without the award, they would have been unable to undertake this important study. The authors would also like to express their appreciation to all those newly qualified doctors who have taken the time to participate. In addition, the authors would like to express thanks to Elaine Russ for providing first-rate project administration support for which they are ceaselessly grateful.

Footnotes

Contributors: AB, KW, RD and MS were involved in the conception and design of the study; AB and KW conducted analysis of the data, and all authors contributed to data interpretation; the article was drafted by KW and AB and revised by the other authors. The final submission has been approved by all.

Funding: This work was supported by the Wales Deanery.

Competing interests: The authors declare they have no personal competing interests. We note that the last named author has a role in Wales Deanery as lead for New Initiatives.

Ethics approval: Postgraduate School of Medical and Dental Education Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. National Academies Press, 2001:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Francis R. The Mid-Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust: public inquiry 2013. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20150407084003/http://www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/report (accessed 2 Jan 2016).

- 3.Health Foundation. Quality improvement made simple 2nd edn 2013. http://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/QualityImprovementMadeSimple.pdf

- 4.Johnson S. ‘Black Wednesday’: share your stories of the day junior doctors start work [online] The Guardian 4 August 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/healthcare-network/2015/aug/04/black-wednesday-share-stories-day-junior-doctors-start-work (accessed 2 Dec 2015).

- 5.Jen MH, Bottle A, Majeed A et al. Early in-hospital mortality following trainee doctors’ first day at work. PLoS ONE 2009;23:e7103 10.1371/journal.pone.0007103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gould M. The killing season [online]. The Guardian 12 May 2004. http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2004/may/12/nhsstaff.health (accessed 2 Dec 2015).

- 7.Bullock A, Dimond R, Webb K et al. How a mobile app supports the learning and practice of newly qualified doctors in the UK: an intervention study. BMC Med Educ 2015;15:71 10.1186/s12909-015-0356-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozdalga E, Ozdalga A, Ahuja N. The smartphone in medicine: a review of current and potential use among physicians and students. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e128 10.2196/jmir.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Connor P, Byrne D, Butt M et al. Interns and their smartphones: use for clinical practice. Postgrad Med J 2014;90:75–9. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-131930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellaway RH, Fink P, Graves L et al. Left to their own devices: medical learners’ use of mobile technologies. Med Teach 2014;36:130–8. 10.3109/0142159X.2013.849800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace S, Clark M, White J. ‘It's on my iPhone’: attitudes to the use of mobile computing devices in medical education, a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001099 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boulos MN, Brewer AC, Karimkhani C et al. Mobile medical and health apps: state of the art. Concerns, regulatory control and certification. Online J Public Health Inform 2014;5(3):229 10.5210/ojphi.v5i3.4814 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3959919/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franzen C. Side effects may vary: the growing problem of unregulated medical apps [online]. The Verge 3 June 2013. http://www.theverge.com/2013/6/3/4380244/how-should-medical-apps-be-regulated (accessed 30 May 2016).

- 14.Bullock AD, Fox F, Barnes R. et al. Transitions in medicine: trainee doctor stress and support mechanisms. J Workplace Learn 2013;25:368–82. 10.1108/JWL-Jul-2012-0052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Bulman M, eds. Analyzing qualitative data. London: Routledge, 1994:305–30. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boaden R. Quality improvement: theory and practice. Br J Healthc Manag 2009;15:12–6. 10.12968/bjhc.2009.15.1.37892 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Health Foundation. Evidence scan: levels of harm 2011. http://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/LevelsOfHarm_0.pdf (accessed 2 Dec 2015).

- 18.GMC. Recognising and approving trainers: the Implementation Plan 2012. http://www.gmc-uk.org/Approving_trainers_implementation_plan_Aug_12.pdf_56452109.pdf

- 19.Øvretveit J. Does improving quality save money? A review of the evidence of which improvements to quality reduce costs to health service providers. London: Health Foundation, 2009:8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department for Health. The NHS outcomes framework 2015/16 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/385749/NHS_Outcomes_Framework.pdf (accessed 2 Dec 2015).

- 21.Karthikeyan G, Pais P. Clinical judgement & evidence-based medicine: time for reconciliation. Indian J Med Res 2010;132:623–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ 1996;312:71–2. 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timmermans S, Berg M. The gold standard: the challenge of evidence-based medicine and standardisation in health care. Temple University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ 2014;348:g3725 10.1136/bmj.g3725 http://www.bmj.com/content/348/bmj.g3725.full.pdf+html [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen D, Harkins KJ. Too much guidance? Lancet 2005;365:1768 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66578-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]