Abstract

Wrist pain due to repetitive motion or overuse is a common presentation in primary care. This case reports the rare condition of intersection syndrome as the cause of the wrist pain in an amateur tennis player. This is a non-infectious, inflammatory process that occurs where tendons in the first extensor compartment intersect the tendons in the second extensor compartment. Suitable history and examination provided the diagnosis, which was confirmed by MRI. Management consisted of early involvement of the multidisciplinary team, patient education, workplace and sporting adaptations, rest, analgesia, reduction of load, protection and immobilisation of the affected joint followed by a period of rehabilitation.

Background

Wrist pain secondary to overuse or repetitive motion is a very common presentation seen in the primary care setting.1 Practitioners often find it daunting to diagnose and manage such conditions inside 10 min. This case report aims to educate general practitioners (GPs) on one particular cause of this type of wrist pain.

Case presentation

Presenting complaint

A 44-year-old right-hand dominant male businessman presented with a 3-month history of right forearm pain. Initially, the pain only affected him when he played tennis, but lately he was also in pain when writing and typing on his computer, which consequently was affecting his performance at work. He said that the pain was just a ‘nuisance’ at first, but the persistent nature of it was worrying him now.

History of presenting complaint

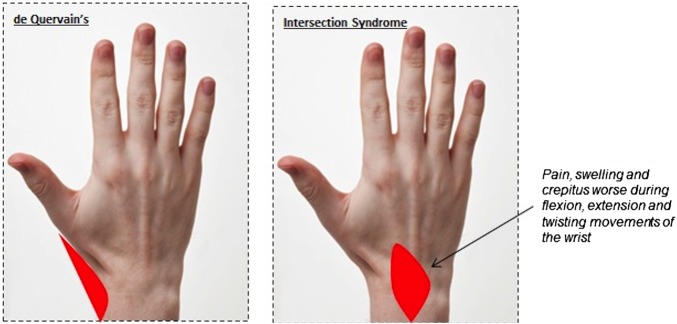

This ‘sharp’ pain started gradually 3 months ago, in the absence of any trauma. It occurred on the dorsal aspect of the radial side of the distal forearm. Initially, it occurred intermittently only during the serve and backhand shots in tennis, but after 6 weeks it occurred continuously whether he was playing tennis or not. Any action that required moving his wrist such as turning a key, writing and typing exacerbated the pain and caused swelling with associated audible crepitus. As the patient would increasingly use his wrist as the day went on, pain was often worse at the end of the day (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diurnal variation graph to show how VAS Score changed throughout the day. VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Sport-specific aspects

He had been playing tennis twice weekly for over 10 years. He had changed his racquet a month prior to the initiation of symptoms and had also started to practice more often in the last 6 months as he was entering a competition at work.

Medical history

He had a greenstick fracture, which was treated non-operatively, in his right forearm as a child after falling off a trampoline and was currently suffering with gout, which was diet controlled.

Medication history

He was not on any regular medications but was using paracetamol, ibuprofen and ice for temporary relief of pain and swelling to his forearm. He did not have any known drug allergies.

Family history

His mother had postmenopausal osteoporosis and osteoarthritis (OA), and his father suffered with gout and OA from a young age.

Social history

He smoked 5–10 cigarettes per day for the last 25 years and was an occasional drinker.

Examination findings

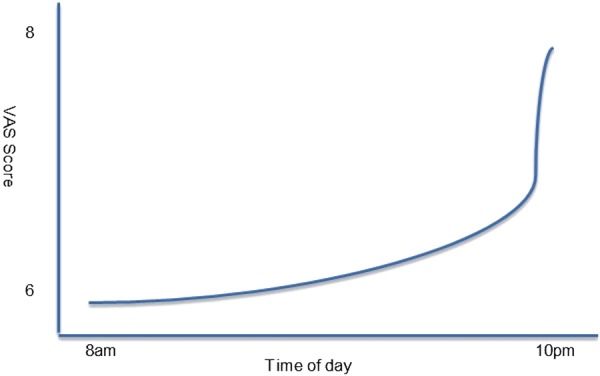

Table 1 lists the findings that were found on examination. These included tenderness, swelling and crepitus proximal to the radial styloid. Pain was worse with movement (figure 2).

Table 1.

Examination findings

| Observation | Area of swelling ∼4 cm proximal to the radial styloid on the dorsum of the forearm. No overlying erythema, scars, contractures, masses, deformities or obvious muscle atrophy. The patient able to point to area of pain with one finger. |

| Palpation | Localised tenderness and audible crepitus at affected area worsened by active more than passive ulnar deviation of wrist. Painful area also mildly warm to touch. No pain at level of neck and upper extremities of arm. |

| Neurological examination | Normal sensation in whole upper limb on cotton wool and pinprick touch. Mild decrease in strength in right wrist due to pain. Nil areas of numbness or paraesthesia. |

| Cardiovascular examination | Radial and ulnar pulses unremarkable. Capillary refill time <2 s. |

| Special orthopaedic tests | Finkelstein's test negative, Eichoff's test positive, Tinel's test negative |

Figure 2.

VAS chart to show pain at rest and during flexion, extension or twisting motion of affected wrist. VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Investigations

No significant findings were ascertained from a simple blood test and plain radiograph that were ordered in the primary care setting. The diagnosis was determined by MRI, which was later performed by the SEM department after referral from the primary care practitioner. The following is a list of investigations that may be suitable in the diagnosis of wrist pain after repetitive movement.

MRI

This is the investigation of choice in this clinical scenario. The anatomy of the first and second extensor compartment crossover has been well demonstrated with short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences being particularly helpful in identifying intersection syndrome.2 3 Peritendinous oedema or fluid surrounding the first and second extensor compartments is seen.3 Other findings may include tendinosis, tendon thickening or muscle oedema.4 On a practical note, it is important to order a forearm examination or clearly describe the region to be investigated as the intersection zone is outside of the area covered by a standard wrist MRI.3 4

Ultrasonography

This can demonstrate findings similar to MRI. As this is an interactive procedure, the probe can be directed specifically to where the pain is, thus allowing dynamic manoeuvres to be performed.3 This is a potential advantage over MRI. It is however heavily operator dependent.

Plain X-ray

This is a suitable initial investigation in a primary care setting if MRI and ultrasonography are not readily available. Posterior–anterior and lateral views are essential. Signs of OA and fracture as well as other bony pathology can be ruled out with X-ray.

Blood tests

Vitamin D, corrected calcium, uric acid and parathyroid levels together with inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein) can help with narrowing down the differential diagnoses but no more, as ultimately a scan will be needed for confirmation of the cause of pain and swelling. Though tophaceous gouty deposits in the wrist are rare, a normal urate level can exclude that unlikely possibility.

Differential diagnosis

The disorder was diagnosed based simply on the history and examination obtained from the patient. MRI confirmed the suspicions of the clinician. Below is a list of differentials that were considered in this case in order of most to least likely.

Intersection syndrome

Intersection syndrome was first described by Velpeau in 1842 as a pain in the dorsal aspect of the forearm 4–8 cm proximal to Lister's tubercle.5 6

Wrist extensor muscles are organised in six compartments over the dorsal aspect of the wrist.7 The most lateral is the first extensor compartment that contains the tendons of the abductor pollicis longus (APL) and extensor pollicis brevis (EPB) muscles.7 Medial to that is the second extensor compartment that contains the tendons of the extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) and extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB).7

There are two theories behind the pathophysiology of intersection syndrome. The first is that pain is caused by friction between the muscle bellies of the APL and EPB with the tendon sheath housing the ECRL and ECRB.8 The other theory is that pain occurs due to entrapment of muscles in the second dorsal compartment due to stenosis.9

Both these aetiologies occur because of overuse of the wrist.10 Pain, crepitus and swelling of the dorsal forearm, 4–8 cm proximal to radial styloid (Lister's tubercle), are the most common presentation, as this is the site of tendon crossover.11

It is known to occur in the occupational setting when there is repeated extension and flexion of the wrist such as one who types or writes a great deal and also in sporting activity where there is repetitive resisted extension of the upper limb such as in tennis.12 13

Level 3 evidence suggests that an incorrect grip of the tennis racquet is related to the anatomical site of lesions in wrist injuries, with non-professionals being more at risk of sustaining injury due to repetition of the unsuitable wrist action.14

Finkelstein's (ulnar deviation of the hand, performed by the examiner, while the thumb is flexed) and Eichoff's (ulnar deviation performed by the patient) tests are tests for de Quervain's tenosynovitis. Finkelstein's is commonly negative in intersection syndrome, though Eichoff's test may produce false positives.9 15

Intersection syndrome has a low prevalence between 0.2% and 0.37% depending on the studies.7 12 Although the reported incidence of intersection syndrome as a cause of distal forearm pain is low, the actual incidence is likely under-reported due to episodes being self-limited, responding quickly to conservative therapy or going unrecognised.16

Though it is commonly unilateral, bilateral cases have been reported.17

De Quervain's tenosynovitis

This is a stenosing tenosynovitis of the first dorsal compartment, which manifests as pain specifically on the radial side of the wrist.18 It is much more common than intersection syndrome.9 Repetitive movement of the affected wrist can also cause it.9 On examination the patient may be swollen and tender over the radial tubercle and sometimes around the anatomic snuff box.18 There is no neurovascular compromise.19 Finkelstein's test is confirmatory because it has good specificity and sensitivity.20 Though Eichoff's test is also positive in de Quervain's, it often produces a false-positive result.15 It is more common in women aged between 30 and 50 years and has been widely reported in new mothers carrying their children.19 21 Figure 3 demonstrates how the location of pain in this case makes intersection syndrome more likely than de Quervain's.

Figure 3.

Illustration to show location of pain in de Quervain's vs intersection syndrome.

Osteoarthritis

This patient may have had OA of the carpometacarpal (CMC) joint or the first dorsal compartment. Clinically, OA is commonly unilateral and can present with pain and swelling similar to this case.22 Often the individual is unable to move their wrist at all as a result of joint stiffness.22 Repetitive motion of the wrist, smoking and a family history of OA may also increase the likelihood of this being the diagnosis.23 However, it occurs more frequently in women over 50 years old and is linked to obesity, joint hyperlaxity and bone and mineralisation factors.23

Wartenberg's syndrome

This is compression of the superficial branch of the radius causing symptoms of a mononeuropathy such as numbness, paraesthesia and weakness of the dorsoradial aspect of the forearm.24 The superficial branch is vulnerable to irritation, trauma and compression, and indeed there have been reports of Wartenberg's occurring in the presence of de Quervain's tenosynovitis.25 Intraneural lipomas and fibrolipomas have been reported to compress the nerve.26 Clinically, they could present as a tender swelling at the wrist joint with a positive Tinel's test.

Treatment

The patient first presented to his GP who advised him to stop playing tennis for a period of 4 weeks. He also advised paracetamol and a topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) for pain relief. As the patient's symptoms persisted, he was then referred to see a specialist in a tertiary care setting.

The primary treatment offered at this point was patient education. The ideas, concerns and expectations of the patient were explored. It transpired that he had not actually rested his wrist joint. As his GP had only advised a cessation to playing tennis, no workplace modifications had been made and so he was still overusing the affected joint on a daily basis. A splint was offered to the patient in order to immobilise the joint. It was stressed to the individual that evidence indicated that absolute immobilisation of the wrist joint and the thumb with splinting in 20° of extension for 3 weeks offered the best chance of early recovery.9 27 As with any overuse injury, intersection syndrome is initially treated using the POLICE principle, that is Protection of the joint, Off-Loading the joint, Immobilise, Compress and Elevate. The wrist splint offered protection, immobilisation and compression of the joint. Off-loading of the joint involved reducing pressure and activity on the joint. The patient was educated as to what daily activities needed to be modified at his workplace, home and social life to achieve this. He was advised to liaise with the occupational health and human resources teams at his workplace to allow him to modify his mode of work. He was advised to elevate the joint by placing it on a pillow during sleep. Although the inflammatory response is an important part of the healing process, early treatment involves limitation of its intensity and duration, as reduced inflammation results in reduced pain which in turn leads to improved physical and psychological well-being of the patient.7 Oral NSAIDs were given to reduce inflammation. Ice therapy applied to the wrist was recommended for the first 72 hours after an acute episode of pain followed by heat therapy after that. The ice therapy results in a reduction in velocity of blood flow to the area applied, which causes reduced pain and swelling. Heat causes localised vasodilatation, which results in increased blood flow and therefore increased oxygen, nutrients and natural anti-inflammatories to the area of pain. Heat was only advised for the chronic pain as it may increase inflammation in an acute setting. Similarly ice was not recommended in a chronic setting as it may exacerbate sensations of stiffness.28 Although there is limited evidence regarding its efficacy, these therapies are non-invasive, cheap, readily available and have relatively few side effects.29 Topical capsaicin and the weak opioid co-dydramol were also prescribed to optimise analgesia. The Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) Score was used to objectify pain levels before and after treatment. On follow-up 3 weeks later, it was found that the VAS Score had only reduced by 1 and so a corticosteroid and a local anaesthetic were injected under ultrasound guidance into the affected area. This was performed, as there is evidence that symptoms may resolve within 10 days of administration.7 9

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was then further followed up 2 weeks later. His symptoms had resolved, and so further injections were not needed. At this point, a physiotherapist was consulted and the frequency, intensity, time and type (FITT) principle was used to formulate a rehabilitation programme that was acceptable to the patient. A 12-week programme of progressive stretching and mobilisation of the joint was devised using the 10% rule (increase in load, sets and repetitions by 10% per week).7 27 Aerobic exercise was encouraged from the start of the rehabilitation process in the form of using a stationary bike with vertical handles to avoid using the wrist. The patient was advised to obtain advise from a tennis coach to understand how to grip and swing the racket appropriately to avoid a similar injury in the future. He was further followed up 6 months later, where VAS Score was now 1 at rest and movement.

Discussion

Wrist injuries secondary to overuse is a common presentation in primary care. Intersection syndrome is one of the less common causes of this. It is an inflammatory condition that occurs at the point of intersection of the first dorsal compartment muscles (APL and EPB) and the radial wrist extensors (ECRL and ECRB).7 27 The condition can be diagnosed simply by history and examination, but ultrasonography and MRI are the imagings of choice to confirm the diagnosis. The mainstay of management is conservative treatment with rest being the most important component. Though GPs have a working knowledge of musculoskeletal medicine, the many nuances in the different pathologies causing this symptom mean that definitive management often is not achieved promptly in a primary care setting. Early involvement of the multidisciplinary team, patient education and formulation of a patient-centred specific rehabilitation programme are key in providing effective management of intersection syndrome.

Learning points.

Intersection syndrome is a rare but important cause of wrist pain due to repetitive motion or overuse.

It is diagnosed clinically but MRI and ultrasonography may be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Conservative therapies including patient education, rest, analgesia, reduction of load and immobilisation of the affected wrist joint and workplace adaptations form the cornerstone of management.

Footnotes

Contributors: JV initially saw the patient at his GP practice. He referred the patient to RC who runs a sports & exercise medicine clinic at Charing Cross Hospital. RC diagnosed, managed and provided rehab for the patient. JV was consulted regarding the outcome. RC wrote the case report with the aid of JV.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Walker-Bone K, Palmer KT, Reading I et al. Prevalence and impact of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb in the general population. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51:642–51. 10.1002/art.20535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Lima JE, Kim HJ, Albertotti F et al. Intersection syndrome: MR imaging with anatomic comparison of the distal forearm. Skeletal Radiol 2004;33:627–31. 10.1007/s00256-004-0832-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiraj S, Winalski CS, Delzell P et al. Radiologic case study. Intersection syndrome of the wrist. Orthopedics 2013;36:165, 225–7 10.3928/01477447-20130222-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee RP, Hatem SF, Recht MP. Extended MRI findings of intersection syndrome. Skeletal Radiol 2009;38:157–63. 10.1007/s00256-008-0587-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grundberg AB, Reagen DS. Pathologic anatomy of the forearm: intersection syndrome. J Hand Surg Am 1985;10:299–302. 10.1016/S0363-5023(85)80129-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Idler RS, Strickland JW, Creighton JJ Jr. Intersection syndrome. Indiana Med 1990;83:658–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jean Yonnet G. Intersection syndrome in a handcyclist: case report and literature review. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2013;19:236–43. 10.1310/sci1903-236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Browne J, Helms CA. Intersection syndrome of the forearm. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2038 10.1002/art.21825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanlon DP, Luellen JR. Intersection syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med 1999;17:969–71. 10.1016/S0736-4679(99)00125-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Servi JT. Wrist pain from overuse: detecting and relieving intersection syndrome. Phys Sportmed 1997;25:41–4. 10.3810/psm.1997.12.1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa CR, Morrison WB, Carrino JA. MRI features of intersection syndrome of the forearm. Am J Roentgenol 2003;181:1245–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Descatha A, Leproust H, Roure P et al. Is the intersection syndrome an occupational disease? Joint Bone Spine 2008;75:329–31. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaneko S, Takasaki H. Forearm pain, diagnosed as intersection syndrome, managed by taping: a case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2011;41:514–19. 10.2519/jospt.2011.3569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tagliafico AS, Ameri P, Michaud J et al. Wrist injuries in nonprofessional tennis players: relationships with different grips. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:760–7. 10.1177/0363546508328112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goubau JF, Goubau L, Van Tongel A et al. The wrist hyperflexion and abduction of the thumb (WHAT) test: a more specific and sensitive test to diagnose de Quervain tenosynovitis than the Eichhoff's test. J Hand Surg Eur 2014;39:286–92. 10.1177/1753193412475043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pantukosit S, Petchkrua W, Stiens SA. Intersection syndrome in Buriram Hospital: a 4-yr prospective study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2001;80:656–61. 10.1097/00002060-200109000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mellick GA, Mellick LB. Bilateral intersection syndrome. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2012;112:98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore JS. De Quervain's tenosynovitis. Stenosing tenosynovitis of the first dorsal compartment. J Occup Environ Med 1997;39:990–1002. 10.1097/00043764-199710000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolf JM, Sturdivant RX, Owens BD. Incidence of de Quervain's tenosynovitis in a young, active population. J Hand Surg Am 2009;34:112–15. 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dawson C, Mudgal CS. Staged description of the Finkelstein test. J Hand Surg Am 2010;35:1513–15. 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson SE, Steinbach LS, De Monaco D et al. “Baby wrist”: MRI of an overuse syndrome in mothers. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004;182:719–24. 10.2214/ajr.182.3.1820719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shehab R, Mirabelli MH. Evaluation and diagnosis of wrist pain: a case-based approach. Am Fam Physician 2013;87:568–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalichman L, Hernández-Molina G. Hand osteoarthritis: an epidemiological perspective. Semin Arthiritis Rheum 2010;39:465–76. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanzetta M, Foucher G. Entrapment of the superficial branch of the radial nerve (Wartenberg's syndrome). A report of 52 cases. Int Orthop 1993;17:342–5. 10.1007/BF00180450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tosun N, Tuncay I, Akpinar F. Entrapment of the sensory branch of the radial nerve (Wartenberg's syndrome): an unusual cause. Tohoku J Exp Med 2001;193:251–4. 10.1620/tjem.193.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balakrishnan C, Bachusz RC, Balakrishnan A et al. Intraneural lipoma of the radial nerve presenting as Wartenberg syndrome: a case report and review of literature. Can J Plast Surg 2009;17:e39–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fulcher SM, Kiefhaber TR, Stern PJ. Upper-extremity tendinitis and overuse syndromes in the athlete. Clin Sports Med 1998;17:433–48. 10.1016/S0278-5919(05)70095-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collins NC. Is ice right? Does cryotherapy improve outcome for acute soft tissue injury? Emerg Med J 2008;25:65–8. 10.1136/emj.2007.051664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malanga GA, Yan N, Stark J. Mechanisms and efficacy of heat and cold therapies for musculoskeletal injury. Postgrad Med 2015;127:57–65. 10.1080/00325481.2015.992719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]