Abstract

Objectives

To systematically assess registration details of ongoing randomised controlled trials (RCTs) targeting 10 common chronic conditions and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov and to determine the prevalence of (1) trial records excluding patients with concomitant chronic condition(s) and (2) those specifically targeting patients with concomitant chronic conditions.

Design

Systematic review of trial registration records.

Data sources

ClinicalTrials.gov register.

Study selection

All ongoing RCTs registered from 1 January 2014 to 31 January 2015 that assessed an intervention targeting adults with coronary heart disease (CHD), hypertension, heart failure, stroke/transient ischaemic attack, atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, painful condition, depression and dementia with a target sample size ≥100.

Data extraction

From the trial registration records, 2 researchers independently recorded the trial characteristics and the number of exclusion criteria and determined whether patients with concomitant chronic conditions were excluded or specifically targeted.

Results

Among 319 ongoing RCTs, despite the high prevalence of the concomitant chronic conditions, patients with these conditions were excluded in 251 trials (79%). For example, although 91% of patients with CHD had a concomitant chronic condition, 69% of trials targeting such patients excluded patients with concomitant chronic condition(s). When considering the co-occurrence of 2 chronic conditions, 31% of patients with chronic pain also had depression, but 58% of the trials targeting patients with chronic pain excluded patients with depression. Only 37 trials (12%) assessed interventions specifically targeting patients with concomitant chronic conditions; 31 (84%) excluded patients with concomitant chronic condition(s).

Conclusions

Despite widespread multimorbidity, more than three-quarters of ongoing trials assessing interventions for patients with chronic conditions excluded patients with concomitant chronic conditions.

Keywords: multimorbidity, PRIMARY CARE, randomized controlled trials, external validity, chronic condition

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study assessing the exclusion of patients with concomitant chronic conditions from ongoing randomised controlled trials (RCTs) registered in ClinicalTrials.gov and assessing interventions for patients with common chronic conditions.

We systematically assessed exclusion criteria reported in trial registration records of RCTs assessing interventions for patients with common chronic conditions and registered in ClinicalTrials.gov according to the prevalence of the co-occurrence of chronic conditions.

Results may not be completely consistent with the exclusion criteria reported in the trial protocol and may underestimate the prevalence of excluding patients with concomitant chronic conditions in trials.

The characteristics of patients actually included in these trials were not assessed. Some patients with concomitant chronic conditions may be excluded by investigators even if no exclusion criterion was listed in the protocol.

Background

Non-communicable chronic conditions are major public health challenges.1 Multimorbidity, defined as the coexistence of chronic conditions, is becoming the norm in primary care settings.2 3 Its prevalence is increasing and represents 23% in the general population; that is, one in four adults is affected.4 Overall, more than half of patients with a chronic condition have multimorbidity5 and have an average of three chronic conditions.6 In the primary care setting, only 2.8–25.4% patients with a common chronic condition have no other chronic conditions.5

Despite this high prevalence of multimorbidity, clinical practice guidelines mainly focus on single chronic conditions and are not relevant for people with multiple chronic conditions.7–10 Indeed, polypharmacy (ie, the chronic coprescription of several drugs) is often the consequence of applying disease-specific guidelines to patients with concomitant chronic conditions. One consequence of polypharmacy is the high rate of adverse drug reactions, mainly from drug–drug interactions, which increase with the number of coexisting diseases and number of drugs prescribed.10 To develop appropriate guidelines for these patients, researchers need high-quality evidence for patients with concomitant chronic conditions, particularly from randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Although we can never have good evidence for every possible combination of conditions,11 RCTs assessing treatment for a specific chronic condition should not exclude patients with concomitant chronic conditions.

This study examined ongoing RCTs targeting 10 common chronic conditions and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov. We assessed the prevalence of trial records excluding patients with concomitant chronic condition(s) and those specifically targeting patients with concomitant chronic conditions.

Methods

We performed a systematic review of records of trials registered at ClinicalTrials.gov and assessing an intervention targeting patients with chronic conditions.

Selection of chronic conditions

We focused on 10 common chronic conditions frequently involved in multimorbidity in primary care settings:5 coronary heart disease (CHD), hypertension, heart failure, stroke/transient ischaemic attack (TIA), atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), painful condition, depression and dementia. We chose these 10 conditions because they are frequent and are frequently associated with concomitant chronic conditions. For instance, only 8.8% of the patients with CHD do not have an associated comorbid condition, 21.9% of those with hypertension, 2.8% with heart failure, 6.0% with stroke/TIA, 6.5% with atrial fibrillation, 17.6% with diabetes, 14.3% with COPD, 12.7% with painful condition, 25.4% with depression and 5.3% with dementia.5 For each of the selected conditions, we used the prevalence of their co-occurrence obtained from UK primary-care electronic health records from a study of the prevalence of multimorbidity in 1.75 million people.5 6

Identification of ongoing RCTs

We identified all ongoing RCTs registered at ClinicalTrials.gov from 1 January 2014 to 31 January 2015 and assessing an intervention targeting patients with 1 of the 10 selected chronic conditions.

Search strategy

We searched ClinicalTrials.gov on 4 March 2015, using the key words ‘coronary heart disease’, ‘hypertension’, ‘heart failure’, ‘stroke’, ‘transient ischemic attack’, ‘atrial fibrillation’, ‘diabetes’, ‘chronic obstructive pulmonary disease’, ‘chronic pain’, ‘depression’ and ‘dementia’ in the Conditions field; ‘recruiting’ in the Recruitment field; ‘Interventional studies’ for Study types; ‘adult (18–65)’ and ‘senior (66+)’ for the Age group; with no restriction on country; and ‘from 1 January 2014 to 31 January 2015’ in the First received field (ie, the date that summary clinical study protocol information was first submitted to the ClinicalTrials.gov registry). We exported all xml records from ClinicalTrials.gov and managed them by using R V.3.0.1 (Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2012) with the XML package.

Study selection

Two independent researchers systematically screened the retrieved records to include all trials assessing an intervention for patients with 1 of the 10 chronic health conditions as a stable chronic condition. Exclusion criteria were phase 0, I and II studies and a target sample size <100 to limit the number of exploratory studies that usually have narrow eligibility criteria. Records were also screened to exclude cost-effectiveness studies, pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic studies, diagnostic studies, development of prediction rules and studies including a specific population (ie, palliative, peripartum and postpartum care).

Data collection

Some data were exported from ClinicalTrials.gov (ie, expected sample size, type of intervention, number of arms); type of outcome and eligibility criteria were recorded and classified by two independent researchers. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion to reach consensus or by arbitration with a third researcher.

General characteristics of the studies

From the records downloaded, we obtained the type of intervention (ie, drugs, device, surgery, behaviour, other), funding source, number of arms and target sample size. The primary outcomes were collected from the Primary Outcome Measures section of ClinicalTrials.gov and were classified as patient-important, surrogate and physiological or laboratory outcomes according to Gandhi et al.12 A patient-important outcome was defined as ‘a characteristic or variable that reflects how a patient feels, functions, or survives’ (ie, all outcomes leading to important changes for patient life).13

Exclusion criteria

For each trial record, the two researchers independently screened the ‘Eligibility’ section. We recorded the number of exclusion criteria and determined whether the trial excluded patients with any concomitant chronic condition(s) (ie, 1 of the 10 chronic conditions selected or any other concomitant chronic condition). Chronic conditions that were not 1 of the 10 chronic conditions considered were classified as ‘any other concomitant chronic condition’. When the chronic condition listed in the exclusion criteria was not clearly defined and could include one of the chronic conditions selected, we considered that the selected chronic condition was listed and that the study excluded patients with these chronic conditions. For example, when psychiatric disorder was listed among the exclusion criteria, we considered that patients with depression were excluded. When an acute stage of the selected chronic conditions was listed in the exclusion criteria, we did not consider that patients with this chronic condition were excluded.

Trials specifically dedicated to patients with concomitant chronic conditions

Researchers screened and recorded the chronic conditions targeted and determined whether the studies specifically included patients with ≥2 chronic conditions.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data are presented as number (percentage) or median (range) for categorical variables and mean (SD) for continuous variables. All analyses involved use of R V.3.0.1 (Team RC. R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2012).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

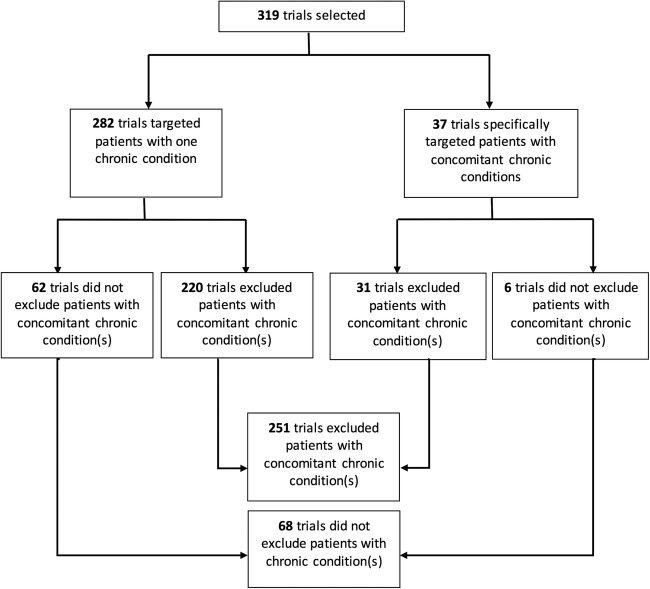

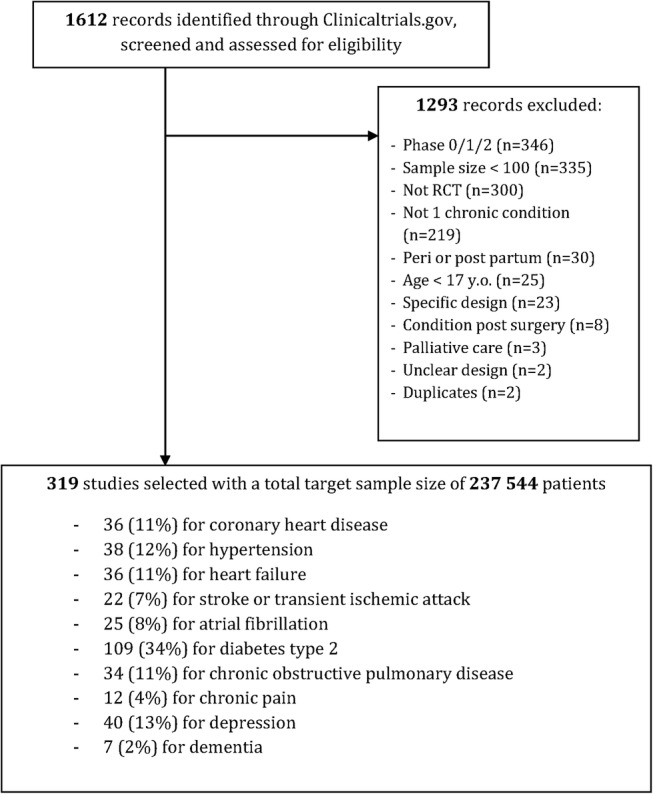

Among the 1612 records retrieved from ClinicalTrials.gov, 319 for ongoing RCTs were selected (figure 1). These trials represented a total target sample size of 237 544 patients. The RCTs targeted CHD in 36 (11%) trials, hypertension in 38 (12%), heart failure in 36 (11%), stroke/TIA in 22 (7%), atrial fibrillation in 25 (8%), diabetes in 109 (34%), COPD in 34 (11%), chronic pain in 12 (4%), depression in 40 (13%) and dementia in 7 (2%) (table 1). Interventions assessed were pharmacological in 147 trials (46.1), and 107 (34%) were funded by industry. Outcomes were classified as patient-important outcomes in 199 (62%) trials.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the selection process.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the 319 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) identified and their focus

| All | CHD | Hypertension | Heart failure | Stroke/TIA | Atrial fibrillation | Diabetes | COPD | Chronic pain | Depression | Dementia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n=319 | n=36 | n=38 | n=36 | n=22 | n=25 | n=109 | n=34 | n=12 | n=40 | n=7 |

| Type of intervention | |||||||||||

| Pharmacological | 147 (46.1) | 11 (30.6) | 21 (55.3) | 11 (30.6) | 4 (18.2) | 9 (36.0) | 62 (56.9) | 24 (70.6) | 3 (25.0) | 13 (32.5) | 4 (57.1) |

| Behavioural | 57 (17.9) | 2 (5.6) | 4 (10.5) | 6 (16.7) | 8 (36.4) | 1 (4.0) | 21 (19.3) | 1 (2.9) | 4 (33.3) | 15 (37.5) | 1 (14.3) |

| Device | 30 (9.4) | 7 (19.4) | 1 (2.6) | 8 (22.2) | 3 (13.6) | 3 (12.0) | 5 (4.6) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Procedure | 18 (5.6) | 9 (25.0) | 1 (2.6) | 3 (8.3) | 1 (4.5) | 8 (32.0) | 2 (1.8) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 40 (12.5) | 4 (11.1) | 5 (13.2) | 5 (13.9) | 5 (22.7) | 1 (4.0) | 10 (9.2) | 6 (17.6) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (20.0) | 2 (28.6) |

| Mixed | 27 (8.5) | 3 (8.3) | 6 (15.8) | 3 (8.3) | 1 (4.5) | 3 (12.0) | 9 (8.3) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (8.3) | 4 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Funding sources | |||||||||||

| Industry profit | 107 (34) | 6 (17) | 14 (37) | 13 (36) | 7 (32) | 5 (20) | 45 (41) | 16 (47) | 3 (25) | 10 (25) | 2 (29) |

| Non-profit | 212 (66) | 30 (83) | 24 (63) | 23 (64) | 15 (68) | 20 (80) | 64 (59) | 18 (53) | 9 (75) | 30 (75) | 5 (71) |

| No. of arms | |||||||||||

| 2 | 249 (78) | 32 (89) | 29 (76) | 32 (89) | 15 (68) | 24 (96) | 83 (76) | 25 (74) | 8 (67) | 32 (80) | 5 (71) |

| 3 | 57 (18) | 4 (11) | 6 (16) | 3 (8) | 5 (23) | 1 (4) | 24 (22) | 8 (23) | 3 (25) | 6 (15) | 0 (0) |

| ≥4 | 13 (4) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (8) | 2 (5) | 2 (29) |

| Targeted sample size | |||||||||||

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 242 (150–483) | 300 (143–559) | 212 (150–351) | 220 (173–442) | 200 (122–540) | 200 (132–420) | 280 (160–480) | 330 (158–983) | 120 (106–296) | 250 (155–375) | 200 (190–527) |

| Type of outcome | |||||||||||

| Patient-important | 199 (62) | 22 (61) | 11 (29) | 29 (81) | 20 (91) | 19 (76) | 40 (37) | 28 (82) | 11 (92) | 39 (98) | 7 (100) |

| Surrogate | 102 (32) | 12 (33) | 25 (66) | 7 (19) | 2 (9) | 3 (12) | 60 (55) | 5 (15) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Laboratory/physiological | 18 (6) | 2 (6) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (12) | 9 (8) | 1 (3) | 1 (8) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

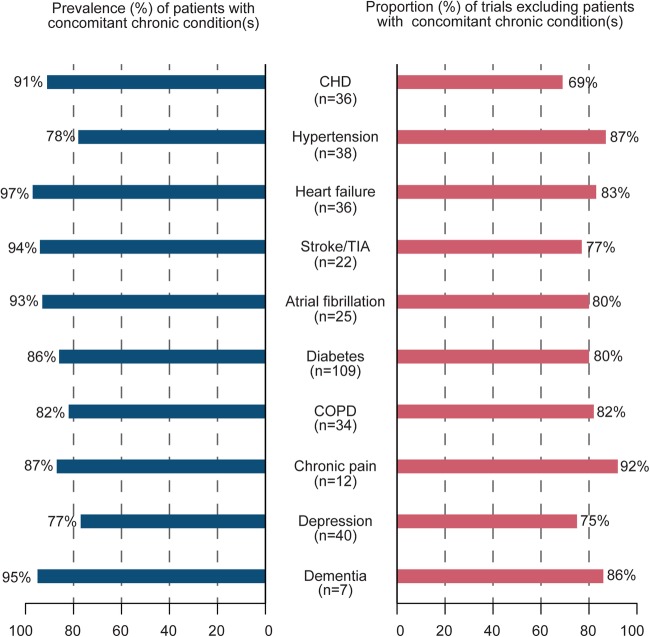

Exclusion criteria

Overall, 251 RCTs (79%) excluded patients with concomitant chronic condition(s) (table 2 and figure 2), with a median of 9 (range 6–14) excluded chronic conditions per trial. Figure 3 shows, for each chronic condition, the proportion of trials excluding patients with concomitant chronic condition(s) by the prevalence of concomitant chronic conditions. For example, although 91% of patients with CHD had a concomitant chronic condition, 69% of trials targeting patients with CHD excluded patients with concomitant chronic condition(s). Similarly, 97% of patients with heart failure had a concomitant chronic condition, but 81% of trials targeting patients with heart failure excluded patients with concomitant chronic condition(s).

Table 2.

Exclusion of patients with concomitant chronic condition(s) in randomised controlled trials

| Characteristics | All | CHD | Hypertension | Heart failure | Stroke/TIA | Atrial fibrillation | Diabetes | COPD | Chronic pain | Depression | Dementia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=319 | n=36 | n=38 | n=36 | n=22 | n=25 | n=109 | n=34 | n=12 | n=40 | n=7 | |

| Trials excluding at least one chronic condition | 251 (79) | 25 (69) | 33 (87) | 30 (83) | 17 (77) | 20 (80) | 87 (80) | 28 (82) | 11 (92) | 30 (75) | 6 (86) |

| Excluded conditions | |||||||||||

| CHD | 47 (15) | – | 10 (26) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 16 (15) | 13 (38) | 0 (0) | 5 (13) | 4 (57) |

| Hypertension | 44 (14) | 4 (11) | – | 3 (8) | 2 (9) | 4 (16) | 18 (17) | 10 (29) | 0 (0) | 4 (10) | 3 (43) |

| Heart failure | 92 (29) | 8 (22) | 15 (40) | – | 0 (0) | 4 (16) | 44 (40) | 20 (59) | 0 (0) | 4 (10) | 3 (43) |

| Stroke/TIA | 37 (12) | 1 (3) | 9 (24) | 1 (3) | – | 1 (4) | 11 (10) | 7 (21) | 1 (8) | 4 (10) | 4 (57) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 34 (11) | 1 (3) | 9 (24) | 2 (6) | 1 (5) | – | 10 (9) | 10 (30) | 0 (0) | 4 (10) | 2 (29) |

| Diabetes | 23 (7) | 1 (3) | 9 (24) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | – | 7 (21) | 1 (8) | 4 (10) | 0 (0) |

| COPD | 6 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 1 (1) | – | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Chronic pain | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | – | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Depression | 53 (17) | 3 (8) | 7 (18) | 3 (8) | 6 (27) | 3 (12) | 14 (13) | 9 (27) | 7 (58) | – | 3 (43) |

| Dementia | 24 (8) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 3 (8) | 4 (18) | 0 (0) | 10 (9) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 5 (13) | – |

| Other(s) | 86 (27) | 12 (33) | 11 (29) | 17 (47) | 6 (27) | 9 (36) | 25 (23) | 4 (12) | 4 (33) | 19 (48) | 1 (14) |

| No. of excluded conditions, median (Q1–Q3) | 9 (6–14) | 11 (7–12) | 12 (6–21) | 10 (6–13) | 8 (5–9) | 9 (7–13) | 8 (6–13) | 13 (7–21) | 10 (6–13) | 8 (4–13) | 10 (8–14) |

| Trials targeting patients with multiple chronic conditions | 37 (12) | 11 (31) | 12 (32) | 7 (19) | 1 (5) | 8 (32) | 14 (13) | 1 (3) | 1 (8) | 7 (18) | 1 (14) |

Data are no. (%) unless indicated.

CHD, coronary heart disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of trial records' eligibility criteria.

Figure 3.

Proportion of trials excluding patients with concomitant chronic condition(s) by prevalence of concomitant chronic conditions. For example, 91% of patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) had a concomitant chronic condition, but 25 trials (69%) targeting patients with CHD excluded patients with concomitant chronic condition(s).

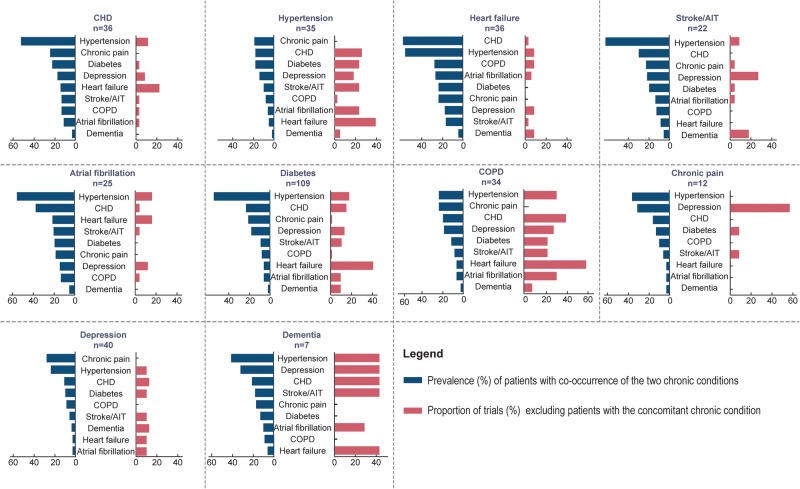

Figure 4 reports the results when considering the prevalence of the co-occurrence of 2 chronic conditions among the 10 selected and shows variation according to the chronic conditions selected. For example, 31% of patients with chronic pain also had depression, but 58% of trials targeting patients with chronic pain excluded patients with depression. Overall, 41% and 32% of patients with dementia had hypertension or depression, respectively, but 43% of trials targeting dementia excluded patients with hypertension or depression.

Figure 4.

For each chronic condition targeted, the proportion of trials excluding patients with 1 of the 10 common chronic conditions selected according to the prevalence of the associations. For example, 61% of patients with stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) also had hypertension, but 9% of the trials targeting patients with stroke/TIA excluded patients with hypertension.

Trials specifically focused on patients with concomitant chronic conditions

Only 37 trials (12%) specifically assessed interventions for patients with ≥2 chronic conditions (figure 2): 34 targeted patients with 2 chronic conditions; 2 targeted patients with 3 chronic conditions and 1 targeted patients with 4 chronic conditions. These 37 trials represent a total target sample size of 17 708 (8%) patients. Patients with diabetes mellitus were included in 14 trials (38%), hypertension in 12 (32%), CHD in 11 (30%), heart failure in 7 (19%), atrial fibrillation in 8 (22%), depression in 7 (19%) and stroke/TIA, chronic pain, dementia and COPD in 1 trial (see online supplementary appendix 1). However, among the 37 trials, 31 (84%) excluded patients with concomitant chronic conditions. Furthermore, the trials did not target several prevalent associations of chronic conditions.

bmjopen-2016-012265supp_appendix.pdf (111.8KB, pdf)

Discussion

This study reports how patients with concomitant chronic conditions are excluded from ongoing RCTs targeting patients with 1 of the 10 chronic conditions frequently involved in multimorbidity. Among 319 ongoing RCTs identified, 251 (79%) excluded patients with concomitant chronic conditions, and the exclusion varied according to the chronic condition targeted. Only 37 trials (12%) assessed interventions specifically targeted to patients with concomitant chronic conditions, and 31 (84%) excluded patients with concomitant chronic condition(s).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing how patients with concomitant chronic conditions are excluded from ongoing RCTs assessing interventions for patients with common chronic conditions. Other studies evaluated exclusion criteria in published RCTs. Van Spall et al14 reviewed published RCTs to determine the nature and extent of exclusion criteria: medical comorbidities (acute and chronic conditions) were excluded in 81% of published RCTs. Jadad et al15 analysed reports of RCTs assessing interventions for patients with chronic conditions published from 1995 to 2010 and found patients with multimorbidity excluded in 65% of published trials. Our results agree with Smith et al,16 who performed a systematic review of all interventional studies assessing interventions specifically directed towards patients defined as multimorbid. The authors retrieved only 10 trials assessing a range of complex interventions.

Our study shows that primary research used to develop guidelines for chronic conditions frequently excludes patients with concomitant chronic conditions,14 so the external validity or generalisability of much of the current evidence is relatively weak.17 Every individual recommendation included in a guideline may be rational and evidence-based, but the sum of all recommendations for patients with multimorbidity may not be.11 Indeed, the inappropriate generalisation of trials results may lead to unintended harm. Research is particularly needed on the clustering of conditions in patients with multimorbidity.18 Few trials are specifically targeting patients with concomitant chronic conditions.

Our study has some limitations. First, we focused on only ongoing trials registered at ClinicalTrials.gov. Although ClinicalTrials.gov is the most commonly used register,19 these records may be not representative of all ongoing trial records. Second, our results relied on exclusion criteria listed in trial records at ClinicalTrials.gov, which may not be complete or may have changed. However, protocols are poorly accessible20 and trial registries are frequently used to assess the trial information.21 Thus, our results may underestimate the prevalence of excluding patients with multiple chronic conditions22 from trial results with protocols. Third, we did not assess the characteristics of the patients actually included in these trials. Some patients with concomitant chronic conditions may be excluded by the investigators even if no exclusion criterion was listed in the protocol. Fourth, the UK prevalence estimates we used to balance our results may not be relevant for all ongoing trial records included.

Chronic conditions and multimorbidity are becoming the greatest epidemic in high-income countries. Management of multimorbid patients is challenging, particularly because clinical practice guidelines are developed in silo for a single disease.23 Physicians are supposed to combine these recommendations when caring for patients with multimorbidity, which can be harmful and burdensome for patients.7 10 Some researchers have called for new forms of clinical practice guidelines and evidence summaries for the management of multimorbidity.11

Our study highlights the need for research of patients with multimorbidity. Assessing the impact of interventions for all associations may not be realistic. However, a clear research agenda on prevalent associations of chronic conditions to produce evidence for caring for these patients is needed. Researchers should also pay attention to eligibility criteria when designing a trial: they should try not to exclude concomitant chronic conditions, so as to be more representative of the real-world population. Finally, our findings may raise a conceptual issue related to the funding of trials: as for guidelines, funding resources are also obtained in silo, condition by condition. Thus, finding resources to finance a trial assessing an intervention for patients with multiple chronic conditions may be difficult.

Conclusion

Despite the high prevalence of multimorbidity, more than three-quarters of ongoing research registered at ClinicalTrials.gov and assessing interventions for patients with chronic health conditions excluded patients with concomitant chronic conditions. This finding could lead to a questionable generalisability of these results to the real-world population. Primary care research should be conducted according to the prevalence of multimorbidity in the real world. The research agenda should be revised to better account for the prevalence of concomitant chronic conditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elise Diard for the graphs and Laura Smales for critical reading and English correction of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors participated in the conception and design of the study. CBdV and CB performed the search, selected the trials and extracted data. CBdV performed the statistical analysis. All authors interpreted the results. CBdV drafted the manuscript and all authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Bauer UE, Briss PA, Goodman RA et al. Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. Lancet 2014;384:45–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60648-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alwan A. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salisbury C, Johnson L, Purdy S et al. Epidemiology and impact of multimorbidity in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e12–21. 10.3399/bjgp11X548929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward BW, Schiller JS, Goodman RA. Multiple chronic conditions among US adults: a 2012 update. Prev Chronic Dis 2014;11:4–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guthrie B, Payne K, Alderson P et al. Adapting clinical guidelines to take account of multimorbidity. BMJ 2012;345:e6341 10.1136/bmj.e6341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lugtenberg M, Burgers JS, Clancy C et al. Current guidelines have limited applicability to patients with comorbid conditions: a systematic analysis of evidence-based guidelines. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e25987 10.1371/journal.pone.0025987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tinetti ME, McAvay G, Trentalange M et al. Association between guideline recommended drugs and death in older adults with multiple chronic conditions: population based cohort study. BMJ 2015;35:h4984 10.1136/bmj.h4984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guthrie B, Makubate B, Hernandez-Santiago V et al. The rising tide of polypharmacy and drug–drug interactions: population database analysis 1995–2010. BMC Med 2015;13:74 10.1186/s12916-015-0322-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dumbreck S, Flynn A, Nairn M et al. Drug-disease and drug–drug interactions: systematic examination of recommendations in 12 UK national clinical guidelines. BMJ 2015;350:h949 10.1136/bmj.h949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace E, Salisbury C, Guthrie B et al. Managing patients with multimorbidity in primary care. BMJ 2015;350:h176 10.1136/bmj.h176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gandhi GY, Murad MH, Fujiyoshi A et al. Patient-important outcomes in registered diabetes trials. JAMA 2008;299:2543–9. 10.1001/jama.299.21.2543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pino C, Boutron I, Ravaud P. Outcomes in registered, ongoing randomized controlled trials of patient education. PLoS ONE 2012;7:8–11. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Spall HGC, Toren A, Kiss A et al. Eligibility criteria of randomized controlled trials published in high-impact general medical journals: a systematic sampling review. JAMA 2007;297:1233–40. 10.1001/jama.297.11.1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jadad AR, To MJ, Emara M et al. Consideration of multiple chronic diseases in randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2011;306:2670–2. 10.1001/jama.2011.1886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith SM, Wallace E, O'Dowd T et al. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;3:CD006560 10.1002/14651858.CD006560.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rothwell PM. Factors that can affect the external validity of randomised controlled trials. PLoS Clin Trials 2006;1:e9 10.1371/journal.pctr.0010009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Violan C, Foguet-Boreu Q, Flores-Mateo G et al. Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of observational studies. PLoS ONE 2014;9: 3–11. 10.1371/journal.pone.0102149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickersin K, Rennie D. The evolution of trial registries and their use to assess the clinical trial enterprise. JAMA 2012;307:1861–4. 10.1001/jama.2012.4230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odutayo A, Altman DG, Hopewell S et al. Reporting of a publicly accessible protocol and its association with positive study findings in cardiovascular trials (from the Epidemiological Study of Randomized Trials [ESORT]). Am J Cardiol 2015;116:1280–3. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.07.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldacre B, Drysdale H, Powell-Smith A et al. The COMPare Trials Project 2016.

- 22.Blümle A, Meerpohl JJ, Rucker G et al. Reporting of eligibility criteria of randomised trials: cohort study comparing trial protocols with subsequent articles. BMJ 2011;342:d1828 10.1136/bmj.d1828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients. JAMA 2005;294:716–24. 10.1001/jama.294.6.716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012265supp_appendix.pdf (111.8KB, pdf)