Abstract

Objective

To capture the clinical patterns, timing of key milestones and survival of patients presenting with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease (ALS/MND) within Australia.

Methods

Data were prospectively collected and were timed to normal clinical assessments. An initial registration clinical report form (CRF) and subsequent ongoing assessment CRFs were submitted with a completion CRF at the time of death.

Design

Prospective observational cohort study.

Participants

1834 patients with a diagnosis of ALS/MND were registered and followed in ALS/MND clinics between 2005 and 2015.

Results

5 major clinical phenotypes were determined and included ALS bulbar onset, ALS cervical onset and ALS lumbar onset, flail arm and leg and primary lateral sclerosis (PLS). Of the 1834 registered patients, 1677 (90%) could be allocated a clinical phenotype. ALS bulbar onset had a significantly lower length of survival when compared with all other clinical phenotypes (p<0.004). There were delays in the median time to diagnosis of up to 12 months for the ALS phenotypes, 18 months for the flail limb phenotypes and 19 months for PLS. Riluzole treatment was started in 78–85% of cases. The median delays in initiating riluzole therapy, from symptom onset, varied from 10 to 12 months in the ALS phenotypes and 15–18 months in the flail limb phenotypes. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy was implemented in 8–36% of ALS phenotypes and 2–9% of the flail phenotypes. Non-invasive ventilation was started in 16–22% of ALS phenotypes and 21–29% of flail phenotypes.

Conclusions

The establishment of a cohort registry for ALS/MND is able to determine clinical phenotypes, survival and monitor time to key milestones in disease progression. It is intended to expand the cohort to a more population-based registry using opt-out methodology and facilitate data linkage to other national registries.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Outcomes and time to key interventions were easily obtained and recorded using the national web-based data entry reducing issues of recall error.

Based on the site of disease onset and distribution of regional involvement, with respect to upper and lower motor neuron signs, patients could be assigned to clinical phenotypes.

Selection bias due to capture and follow-up of patients from specialised clinics could alter outcomes and survival compared with those not attending specialised clinics.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) has a heterogeneous clinical presentation, with consequent variability in disease progression and survival.1 The clinical categories and nosology of ALS have evolved over many years of observational studies resulting in a defined set of diagnostic criteria.2–5 The health service needs of ALS patients and their carers require integrated services across the allied health disciplines along with neurology, respiratory and palliative medicine specialists.6–8 A critical issue remains the timely diagnosis, clinical classification and prognostic stratification (staging) of patients that facilitate appropriate care plans. The primary objective of the Australian Motor Neurone Disease (MND) registry was to develop accurate clinical phenotyping and survival data, enabling early pathways to interventions and clinical trial enrolment.9–12

There have been advances in prognostic modelling for survival and staging of ALS/MND.11 13 In addition, the use of patient registries and cohort studies to monitor disease-specific patient care and outcomes has developed worldwide over the past decade. Evidence from the Irish Registry indicated that attendance at ALS multidisciplinary clinics itself conferred a survival advantage.14 Disease registries provide effective mechanism to further optimise and inform clinical care and actively recruit into clinical trials, bio-banking and research programmes for ALS/MND. International data linkage will be essential in furthering our understanding and delivering the promise of treatments and a cure for ALS (NETCALS, EURO-MOTOR, CARE). The Australian National MND registry represents the Australian experience and provides a potentially practical mechanism for clinical phenotyping, monitoring and benchmarking clinical practice at a national level.

The Australian MND registry is an observational cohort study initiated in 2004.15 16 This registry has collected a data set of, demographic, clinical profiles and disease progression data at a national level from 2005 to 2015.15 In Australia, this methodology was initially developed within a single comprehensive ALS clinic,17 and then expanded to a national level. The primary aim of the national registry was to help coordinate focused care and a foundation for case ascertainment for research in ALS/MND.

Methods

Consecutive patients in whom the treating neurologist felt had a likely diagnosis of ALS/MND were invited to participate in the national registry. ALS/MND care delivery in Australia is through 10 major clinics and the state-based motor neuron disease associations. These ALS/MND clinics provide comprehensive care with allied health teams. In most clinics, there is a link to the MND associations of each state. Ethics approval was obtained from appropriate institutional review committees across each state and prior to enrolment in the registry. Patients gave written informed consent for their participation. Non-English-speaking patients were required to have an English-speaking care provider/relative or an interpreter to provide informed consent before data collection. Patients incapable of providing written consent needed a witness to sign and acknowledge verbal consent. In 2013, opt-out consent was instituted as the method of registration in the State of Victoria. Patients registered who were later deemed not to have ALS were removed from the analysis after submission of a completion clinical report form (CRF).

Once registered, patient baseline details were entered using a registration CRF. Further CRFs were submitted at varying intervals as part of patient's ongoing clinical assessments. Information collected at registration and follow-up reviews related to the clinical history of disease and its progression, current clinical signs, medications, respiratory function, body weight, clinical interventions and health service utilisation. The findings on neurological examination were designed to identify specific clinical phenotypes. Further information in the domains of evolution of clinical signs, ALSFRS-r, diagnostic tests, body weight and respiratory function are gathered at subsequent clinical reviews. Timing of interventions, including percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), medications and non-invasive ventilation (NIV), along with health service utilisation are prospectively collected. The data set was analysed using R (http://www.r-project.org/). Patients included in the analysis all had a completed registration CRF, with date of birth, time and region of symptom onset, there were no missing data.

Patients were enrolled in the cohort registry using a web-based system which produced a unique patient identification number for each patient entered. The link between the patient's identity and the patient ID number was kept secure at each study site. Once registered, the patient ID number, study centre number and investigator number were required for all data entry.

Clinical phenotypes

A primary aim of this cohort study was to determine whether ALS/MND patients could be classified into clinical phenotypes at a national level across multiple ALS/MND clinics. The rationale for this was to facilitate clinical care and research based on an appropriate patient stratification and then benchmark between centres in relation to major interventions and survival.18

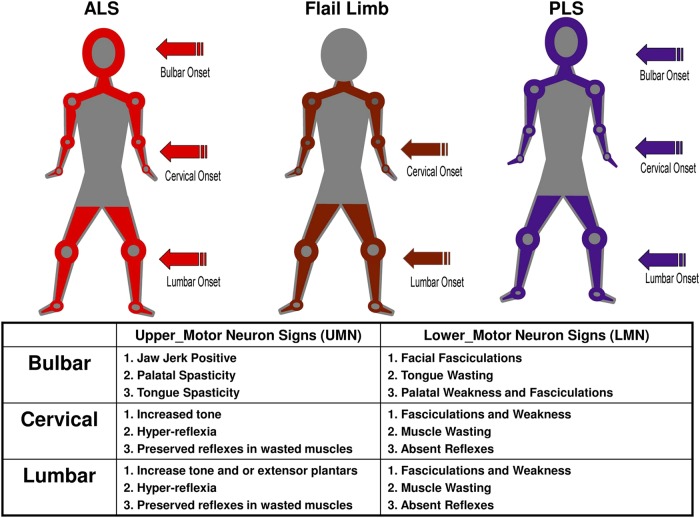

The methodology for determining the three major clinical phenotypes was adapted from an initial study undertaken in a large multidisciplinary ALS MND clinic and a previous studies analysis of flail phenotypes.17 19 The region of symptom onset is combined with the observed clinical UMN/LMN signs in the bulbar, cervical and lumbar regions (figure 1). Those patients without such clinical information in the CRF were defined as undifferentiated. Phenotyped patients were also given an El Escorial classification based on the clinical information in the most recent CRF.2 3 The three major clinical phenotypes, as adapted from El Escorial, are illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

The clinical phenotypes are detailed, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, flail and primary lateral sclerosis (PLS). Clinical phenotypes are allocated by identifying the region of symptom onset combined with the segmental distribution of upper and lower motor neuron signs. Patients with combined upper and lower motor neuron signs in one segment with at least one other segment involved with either upper motor neuron (UMN) and/or lower motor neuron (LMN) signs are classified into a clinical phenotype. Flail arm have the initial onset of LMN signs in the arms and absent arm reflexes. They have UMN and/or LMN signs in the legs and variable bulbar involvement and evolving neck weakness. Flail leg begin with LMN signs in the legs and areflexia, which extend to the arms with very late bulbar involvement. PLS is defined by having only UMN signs in all three segments; the onset can be in any region. Definitions for UMN and LMN signs for each region are listed. In order to maintain consistency, a region required the presence of at least one of the predefined clinical signs listed in the panel in order to be designated as having UMN, LMN or combined UMN/LMN signs.

Survival and clinical phenotypes interventions and outcomes

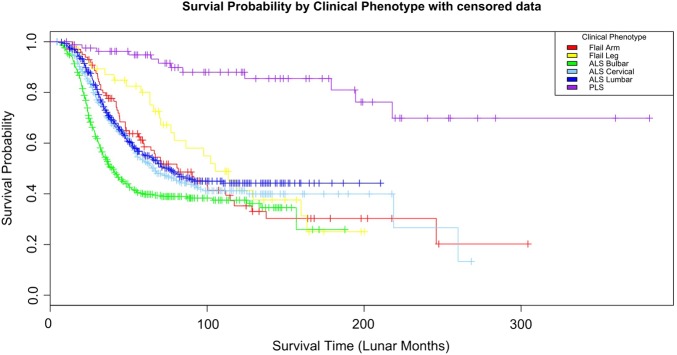

Patient survival was determined from the date of symptom onset to the date of death. Death was reported via submission of a completion CRF. For the Kaplan-Meier curves, patients were censored at the time of death according to the allocated clinical phenotype (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of patients censored at the time of death according to clinical phenotype. Survival according to the phenotypes with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis bulbar, onset having significantly different curves to flail arm and leg (p<0.003 and <0.004).

Results

Registrations

A total of 1834 patients were registered in the cohort study between 2005 and 2015. In 1677 (90%) patients, a registration CRF was available and these were included in the analysis. Ten major centres from around Australia accounted for 95% of all patient registrations. This study cohort overall had a gender ratio male to female of 1.5:1.0, with registration in AMNDR occurring at a median of 17 months from symptom onset. The number, gender, age at onset, time to registration and number of deaths for each site in the study cohort are detailed in table 1.

Table 1.

The number of registered patients (% percentage of) according to clinical phenotype, gender, median age of symptom onset and El Escorial classification

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cases | Bulbar onset | Cervical onset | Lumbar onset | Flail arm | Flail leg | Undifferentiated | PLS | |

| Total number | 1677 | 429 (26%) | 396 (24%) | 450 (27%) | 101 (6%) | 47 (3%) | 156 (9%) | 84 (5%) |

| Gender ratio | ||||||||

| M:F | 1 : 0.70 | 1 : 1 | 1 : 0.42 | 1 : 0.71 | 1 : 0.25 | 1 : 0.56 | 1 : 0.66 | 0.91 : 1 |

| Median age at onset (years) | 63 | 66 | 59 | 63 | 65 | 61 | 64 | 61 |

| El Escorial classification | ||||||||

| Definite | 364 | 191 (44%) | 81 (20%) | 81 (18%) | 0 | 0 | – | 0 |

| Probable | 693 | 149 (35%) | 222 (56%) | 310 (69%) | 10 (10%) | 2 (4%) | – | 0 |

| Possible | 281 | 77 (18%) | 86 (22%) | 57 (12%) | 35 (35%) | 10 (21%) | – | 18 (22%) |

| Suspected | 185 | 12 (3%) | 7 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 56 (55%) | 35 (75%) | – | 66 (78%) |

According to gender, the median age of symptom onset was similar for all centres (male 60 years; female 62 years). Each centre contributed a similar percentage of completion CRFs which provided the date of death and survival data. Assuming an incidence of 2/100 000 in Australia,20 there would have been ∼5000 incident cases of ALS during 2004–2014. As such, the present study cohort would represent ∼35% of incident ALS cases in Australia during the study period.

Clinical phenotyping

The ALS phenotype (bulbar, cervical and lumbar onset) was the most frequent phenotype, accounting for 1275 (76%) of the cohort cases (table 1). Within the ALS phenotypes, the subgroups were evenly distributed: bulbar onset 26%, cervical onset 24% and lumbar onset 27% (table 1). Flail limb subgroups represented 9%, undifferentiated group 9% and primary lateral sclerosis (PLS) 5% of all cases (table 1). Importantly, the major sites registered similar percentages of patients across each of the clinical phenotypes, providing some confidence that the methodology was broadly applicable. The undifferentiated entity provided a clinical ‘holding pattern’ for those cases where there was diagnostic uncertainty and an inability to allocate a clinical phenotype based on the entered data. As subsequent assessments were entered if patients fulfilled the classification criteria, their clinical phenotype was updated.

The gender ratios for the different clinical phenotypes indicated a clear male predominance for all phenotypes with the exception of ALS bulbar onset (table 1). As previously shown, this subgroup has a high proportion of females compared with other subgroups.17 The flail arm and leg phenotypes have a much higher proportion of males to females as has been established in other studies.19

Sixty-three per cent of the cohort were defined as definite or probable ALS using the El Escorial classification (table 1). The ALS phenotypes contributed 62% of all definite or probable El Escorial cases, ALS bulbar onset contributing 20%, ALS cervical onset 18% and ALS lumbar onset 23% (table 1). The flail groups contribute much less to the definite and probable El Escorial groups, 1% in total. The undifferentiated were not classified into a phenotypic group or given an El Escorial classification.

Survival

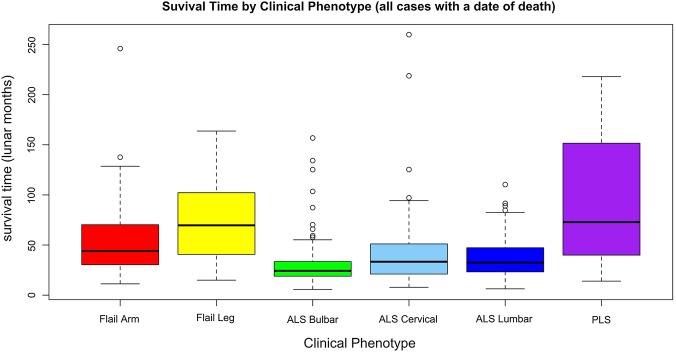

Of all 763 patients with a date of death from the present cohort, the ALS bulbar onset exhibited the shortest median survival of 24 months from symptom onset, while PLS had the longest, 73 months (figure 3). The survival of ALS bulbar onset was significantly different from all other phenotypes consistent with other reports on ALS survival.14 21 22 The Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves for clinical phenotypes are also similar to other reports (figure 2). The undifferentiated group had similar survival curves to ALS cervical/lumbar onset. It is conjecture whether the clinical phenotypes relate to variations in pathophysiology, but they do represent patients with similar survival times and clinical care requirements.

Figure 3.

All cases with a reported date of death, median (StdDev) survival in lunar months according to clinical phenotype.

Timelines to key milestones and clinical interventions according to clinical phenotype

The median time to diagnosis from symptom onset in the ALS phenotypes was 10–12 months. The flail group required 14–18 months and PLS the longest, at a median of 19 months (table 2).

Table 2.

Delay in diagnosis from symptom onset according to clinical phenotype (median; months) and time to key interventions from symptom onset (riluzole treatment, non-invasive ventilation and percutaneous gastrostomy), with the percentage of patients in the clinical phenotype who received the intervention

| Phenotype | Total in phenotype | Diagnosis from symptom onset median time, months | Riluzole treatment median time, months (n, % of phenotype) | Non-invasive ventilation median time, months (n, % of phenotype) | Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy median time, months (n, % of phenotype) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALS bulbar onset | 429 | 10 | 10 (333, 78) | 17 (68, 16) | 17 (156, 36) |

| ALS cervical onset | 396 | 11 | 11 (337, 85) | 18 (88, 22) | 21 (48, 12) |

| ALS lumbar onset | 450 | 12 | 12 (358, 80) | 23 (78, 17) | 24 (35, 8) |

| Flail_arm | 101 | 14 | 15 (83, 82) | 33 (29, 29) | 43 (9, 9) |

| Flail_leg | 47 | 18 | 18 (38, 81) | 37 (10, 21) | 34 (1, 2) |

| PLS | 84 | 23 | 16 (46, 55) | 23 (9, 11) | 15 (12, 14) |

Diagnostic delay reflects a multitude of variables which are related to health systems, referral patterns and the difficulty of establishing a diagnosis in ALS. These data provide a basis for analysis of any future intervention designed to impact on diagnostic delay (such as a diagnostic biomarker or health system change) at a national and individual clinic level.

The initiation of riluzole treatment closely followed diagnosis and had a consistent uptake across all ALS phenotypes being between 78% and 85% of cases with a median delay of 10–12 months from symptom onset (table 2). The time from symptom onset to NIV and PEG tube insertion are reflective of the natural progression of ALS (table 2). The percentage of cases getting PEG interventions is uniform across the clinical phenotypes with the exception of ALS bulbar onset which has the highest rate of insertion, 36% of cases with a median time to insertion of 17 months from symptom onset. Flail leg had only one case of PEG insertion which is consistent with the lack of bulbar involvement in this form of MND. The rates for PEG insertion and time to insertion are consistent with other reported studies, with bulbar onset disease is more likely to undergo PEG insertion.23–25 NIV appeared to be uniformly applied across the different phenotypes, with the flail limb phenotype having the longest interval from symptom onset to initiation of NIV (33–37 months). Overall, the rates of implementation NIV are similar to reported studies in North America and Europe.26 27 There were no patients reported in the registry who underwent tracheostomy. In the PLS group, it is interesting to note that riluzole treatment and PEG insertion preceded the confirmation of diagnosis (table 2).

Discussion

The primary objective of the present study was to determine whether clinical phenotypes could be identified in a national registry across multiple ALS/MND clinics. The present data provide a platform from which clinical phenotyping/staging of ALS patients with similar survival trajectories can be compared between treatment centres. This cohort is in line with previous studies evaluating clinical phenotypes and survival characteristics.19 26 28 29 Preliminary analysis demonstrated that the ALS phenotype was the predominate group in the clinically definite and probable El Escorial categories. The present categorisation of patients utilised a simple algorithm that is readily applied during routine clinic consultations. This approach has proven sustainable at a national level over the past 10 years and, as such, provides a foundation for delivery of care, benchmarking, quality and safety monitoring and potentially more detailed research on the effect of therapies and interventions.

The time to diagnosis remains lamentably long and any advances that shorten this period will deliver benefits to ALS patients and their carers. This is as much to do with provision of resources and referral patterns, as it is to do with the difficulty of making a diagnosis in ALS/MND. It would be interesting to determine what future interventions will reduce the delay in diagnosis at the individual centre and national level.

Some major issues regarding cohort data are the biases incurred from the opt-in consent methodology and patient enrolments from specialist centres which can skew the outcomes.30 31 The introduction of opt-out consent may enhance case ascertainment, making outcome analysis more representative of a population-based approach to data acquisition. As the functionality of patient registries evolve, especially in rare diseases, new methods of patient participation, data acquisition and methods of analysis will need to be explored.32 33

The refinement of staging disease progress will further enhance clinical management of ALS. Clinical phenotyping and staging should be designed to provide complementary information. This approach may assist in the discovery of biomarkers by providing analysis of patients with similar clinical patterns and stage of disease. The effort of developing and refining these investigative methodologies will prove to be valuable assets in trial design, recruitment and implementation.34 35 Clinical phenotyping and staging will inevitably permit better randomisation in clinical trials and facilitate more relevant outcome measures and an accurate assessment of disease progression. The Australian MND registry will now undergo revision and expansion of data-fields, incorporating metrics of disease progression and quality-of-life measures. Consent for de-identified data collection will be changed from opt-in to opt-out across Australia. Registries have the potential to be a single point for enrolling and phenotyping patients for proteomic/genomic analysis and therapeutic trials.

Conclusions

The Australian MND registry has proven to be a successful and sustainable method of registering, phenotyping and observing key interventions in ALS/MND treatment. It provides the ability to benchmark between centres and provides national averages for key interventions and disease progression. Further international data-linkage, opt-out methodology for registration and the addition of patient initiated information may further enhance data quality and clinical trial enrolment.

Acknowledgments

The Australian MND registry acknowledges the effort of the research associates and clinical nurse consultants who have contributed to the data acquisition and clinical care of patients. Patients and their carers are thankfully acknowledged for taking what is precious time to be part of the national registry.

Footnotes

Contributors: PT, SM, RH, DR, SV, DS, RE, MN, RM, PM and MK designed and established the Australian Motor Neurone Disease National registry. PT was responsible for governance and coordination of the registry. TD, SV and PT performed data cleaning and statistical analysis. All authors contributed to writing and critical editing the manuscript and approval for publication.

Funding: This registry was supported by an unrestricted education grant from sanofi aventis, the Motor Neurone Disease Association of Australia, Westfield and Pratt Foundations.

Disclaimer: The authors were solely responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This registry has ethics approval from: Barwon Health Medical Research Ethics committee EC00208: Calvary Health Care Medical Research Ethics committee EC00421: Sydney Local Health District Ethics committee EC00113 (RPAH Zone), through a National Ethics Application (NEAF). The NEAF (AU/1/8F2A110) was approved at participating site local ethics committees.

Data sharing statement: The data fields within the Australian MND Registry used in this analysis are available for data sharing as a CSV Excel file format. The data will be provided on application to the lead author (Associate Professor PT, Neurosciences Department University Hospital Geelong, PO Box 281 Geelong, VIC 3220, Australia. Email: pault@barwonhealth.org.au) with final approval on review of the application by the Australian MND Registry Steering Committee. Other unpublished data in the Australian MND Registry are not currently available for data sharing.

References

- 1.Kiernan MC, Vucic S, Cheah BC et al. . Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 2011;377:942–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61156-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks BR. El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria for the daignosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Subcommittee on Motor Neuron Disease/Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis of the World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Neuromuscular Diseases and the El Escorial ‘Clinical Limits of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis’ workshop contributors. J Neurol Sci 1994;124(Suppl):96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Neuromuscular Diseases Subcommittee on Motor Neuron Disease. Airlie House Guidelines. Therapeutic trials in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Airlie House ‘Therapeutic trials in ALS’ Workshop Contributors. J Neurol Sci 1995;129:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ludolph A, Drory V, Hardiman O et al. . A revision of the El Escorial criteria—2015. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2015;16:291–2. 10.3109/21678421.2015.1049183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Carvalho M, Dengler R, Eisen A et al. . The Awaji criteria for diagnosis of ALS. Muscle Nerve 2011;44:456–7. author reply 7 10.1002/mus.22175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corr B, Frost E, Traynor BJ et al. . Service provision for patients with ALS/MND: a cost-effective multidisciplinary approach. J Neurol Sci 1998;160(Suppl 1):S141–5. 10.1016/S0022-510X(98)00214-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swash M. Lithium time-to-event trial in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis stops early for futility. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:449–51. 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70085-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ng L, Talman P, Khan F. Motor neurone disease: disability profile and service needs in an Australian cohort. Int J Rehabil Res 2011;34:151–9. 10.1097/MRR.0b013e328344ae1f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardiman O, Corr B, Frost E et al. . Access to health services in Ireland for people with multiple sclerosis and motor neurone disease. Ir Med J 2003;96:200–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardiman O, Traynor BJ, Corr B et al. . Models of care for motor neuron disease: setting standards. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 2002;3:182–5. 10.1080/146608202760839002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roche JC, Rojas-Garcia R, Scott KM et al. . A proposed staging system for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2012;135(Pt 3):847–52. 10.1093/brain/awr351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Chalabi A. The multidisciplinary clinic, quality of life and survival in motor neuron disease. J Neurol 2007;254:1118 10.1007/s00415-006-0387-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scotton WJ, Scott KM, Moore DH et al. . Prognostic categories for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2012;13:502–8. 10.3109/17482968.2012.679281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Traynor BJ, Alexander M, Corr B et al. . Effect of a multidisciplinary amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) clinic on ALS survival: a population based study, 1996–2000. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:1258–61. 10.1136/jnnp.74.9.1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiernan MC, Talman P, Henderson RD et al. . AMNDR Steering Committee. Establishment of an Australian motor neurone disease registry. Med J Aust 2006;184:367–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talman P, Rowe D, Kiernan M. Australian Motor Neuon Disease Registry (AMNDR). J Neurol Sci 2005;238(Suppl 1):S214. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talman P, Forbes A, Mathers S. Clinical phenotypes and natural progression for motor neuron disease: analysis from an Australian database. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2009;10:79–84. 10.1080/17482960802195871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beghi E, Chiò A, Couratier P et al. . The epidemiology and treatment of ALS: focus on the heterogeneity of the disease and critical appraisal of therapeutic trials. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2011;12:1–10. 10.3109/17482968.2010.502940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wijesekera LC, Mathers S, Talman P et al. . Natural history and clinical features of the flail arm and flail leg ALS variants. Neurology 2009;72:1087–94. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000345041.83406.a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traynor BJ, Codd MB, Corr B et al. . Incidence and prevalence of ALS in Ireland, 1995–1997: a population-based study. Neurology 1999;52:504–9. 10.1212/WNL.52.3.504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiò A, Logroscino G, Hardiman O et al. . Prognostic factors in ALS: a critical review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2009;10:310–23. 10.3109/17482960802566824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rooney J, Byrne S, Heverin M et al. . Survival analysis of Irish amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients diagnosed from 1995–2010. Plos ONE 2013;8:e74733 10.1371/journal.pone.0074733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiò A, Silani V. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis care in Italy: a nationwide study in neurological centers. J Neurol Sci 2001;191:145–50. 10.1016/S0022-510X(01)00622-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marin B, Beghi E, Vial C et al. . Evaluation of the application of the European guidelines for the diagnosis and clinical care of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients in six French ALS centres. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:787–95. 10.1111/ene.12941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitsumoto H, Davidson M, Moore D et al. . Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) in patients with ALS and bulbar dysfunction. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 2003;4:177–85. 10.1080/14660820310011728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiò A, Calvo A, Moglia C et al. . Phenotypic heterogeneity of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82:740–6. 10.1136/jnnp.2010.235952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller RG, Anderson F, Brooks BR et al. . Outcomes research in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: lessons learned from the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis clinical assessment, research, and education database. Ann Neurol 2009;65(Suppl 1):S24–8. 10.1002/ana.21556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ganesalingam J, Stahl D, Wijesekera L et al. . Latent cluster analysis of ALS phenotypes identifies prognostically differing groups. Plos ONE 2009;4:e7107 10.1371/journal.pone.0007107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Statland JM, Barohn RJ, McVey AL et al. . Patterns of weakness, classification of motor neuron disease, and clinical diagnosis of sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurol Clin 2015;33:735–48. 10.1016/j.ncl.2015.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berry JG, Ryan P, Braunack-Mayer AJ et al. . A randomised controlled trial to compare opt-in and opt-out parental consent for childhood vaccine safety surveillance using data linkage: study protocol. Trials 2011;12:1 10.1186/1745-6215-12-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Junghans C, Feder G, Hemingway H et al. . Recruiting patients to medical research: double blind randomised trial of ‘opt-in’ versus ‘opt-out’ strategies. BMJ 2005;331:940 10.1136/bmj.38583.625613.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wicks P, Vaughan TE, Massagli MP et al. . Accelerated clinical discovery using self-reported patient data collected online and a patient-matching algorithm. Nat Biotechnol 2011;29:411–14. 10.1038/nbt.1837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bohensky MA, Jolley D, Sundararajan V et al. . Data linkage: a powerful research tool with potential problems. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:346 10.1186/1472-6963-10-346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leigh PN, Swash M, Iwasaki Y et al. . Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a consensus viewpoint on designing and implementing a clinical trial. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 2004;5:84–98. 10.1080/14660820410020187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chio A, Canosa A, Calvo A. Prospective epidemiological registers: a valuable tool for uncovering ALS pathogenesis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82:1066 10.1136/jnnp.2011.246876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]