Abstract

Objective

To investigate patients' values and preferences regarding aortic valve replacement therapy for aortic stenosis.

Setting

Studies published after transcatheter aortic valve insertion (TAVI) became available (2002).

Participants

Adults with aortic stenosis who are considering or have had valve replacement, either TAVI or via surgery (surgical aortic valve replacement, SAVR).

Outcome measures

We sought quantitative measurements, or qualitative descriptions, of values and preferences. When reported, we examined correlations between preferences and objective (eg, ejection fraction) or subjective (eg, health-related quality of life) measures of health.

Results

We reviewed 1348 unique citations, of which 2 studies proved eligible. One study of patients with severe aortic stenosis used a standard gamble study to ascertain that the median hypothetical mortality risk patients were willing to tolerate to achieve full health was 25% (IQR 25–50%). However, there was considerable variability; for mortality risk levels defined by current guidelines, 130 participants (30%) were willing to accept low-to-intermediate risk (≤8%), 224 (51%) high risk (>8–50%) and 85 (19%) a risk that guidelines would consider prohibitive (>50%). Study authors did not, however, assess participants' understanding of the exercise, resulting in a potential risk of bias. A second qualitative study of 15 patients identified the following factors that influence patients to undergo assessment for TAVI: symptom burden; expectations; information support; logistical barriers; facilitators; obligations and responsibilities. The study was limited by serious risk of bias due to authors' conflict of interest (5/9 authors industry-funded).

Conclusions

Current evidence on patient values and preferences of adults with aortic stenosis is very limited, and no studies have enrolled patients deciding between TAVI and SAVR. On the basis of the data available, there is evidence of variability in individual values and preferences, highlighting the importance of well-informed and shared decision-making with patients facing this decision.

Trial registration number

PROSPERO CRD42016041907.

Keywords: GRADE, Shared decision making, TAVI, aortic stenosis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review of patient values and preferences regarding aortic stenosis valve replacement therapy.

Our results informed the BMJ-RapidRecs guideline on transcatheter aortic valve insertion versus surgical aortic valve replacement for low-to-intermediate surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis.

The variability of our findings demonstrated the importance of shared decision-making.

There were only two studies on this topic, and both were among high-risk patients, which limited the generalisability of our findings.

Introduction

Severe symptomatic aortic stenosis is a relatively common condition among older populations, with serious consequences including heart failure and markedly increased mortality.1 The prevalence of aortic stenosis increases with age and is over 3% in those >75 years of age.2 3 With increasing severity of stenosis, patients often experience chest pain, syncope, heart failure and sudden death.4

Although medical management is an option in the care of patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, it is usually in the context of a palliative approach to management. Substantial amelioration of symptoms, and prolonged survival, requires aortic valve replacement (AVR). Options for valve replacement include open-heart surgery (surgical aortic valve replacement, SAVR), available since the 1960s, or a novel, less invasive procedure, in which a new valve is inserted without open-heart surgery (transcatheter aortic valve implantation, TAVI), first performed in 2002 but with limited availability outside of clinical trials until recently.5 TAVI has proved practice changing, because it is feasible in patients otherwise at high or extreme risk with SAVR, commonly defined as a risk score of 8% or higher on the Society of Thoracic Surgery predictive risk of mortality (STS-PROM).6–8 Following a recent trial of patients with severe aortic stenosis at low-to-intermediate risk for perioperative complications, two systematic reviews have demonstrated that transfemoral TAVI versus SAVR reduces mortality and stroke over the short term but increases the risk of heart failure in this population; its impact on long-term outcomes remains uncertain (R A Siemieniuk, T Agoritsas, V Manja, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in low and intermediate risk patients with severe aortic stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, co-submitted).9 10

Clinicians' appraisal and patients' appraisal of benefits and harms may differ, and values and preferences are likely to differ among patients with similar health states.11 Therefore, it is of high relevance to understand, with the best available evidence, patient's values and preferences in settings where real therapeutic choices exist. Particularly in patients with severe aortic stenosis between 65 and 85 at low-to-moderate perioperative risk, TAVI versus SAVR represents as such a value and preference sensitive choice (R A Siemieniuk et al. BMJ, co-submitted; P O Vandvik, C M Otto, R A Siemieniuk, et al. For those with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis is transcatheter or open surgical aortic valve replacement in those at low to intermediate risk surgical risk? A clinical practice guideline. BMJ, co-submission).

Making recommendations for clinicians and patients requires that guideline panels have an understanding of the determinants of patients' choices. Patient values and preferences are a key factor when moving from evidence to recommendations.12 We therefore conducted a systematic review of patients' values and preferences related to outcomes of TAVI and SAVR in the management of aortic stenosis. Our systematic review was initiated to inform the first BMJ-RapidRecs (P O Vandvik, C M Otto, R A Siemieniuk et al. Transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement for patients with severe, symptomatic, aortic stenosis at low to intermediate surgical risk: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ, co-submission), a new BMJ series of trustworthy recommendations published in response to potentially practice-changing evidence (R A Siemieniuk, T Agoritsas, H Macdonald, et al. Editorial: Introduction to BMJ Rapid Recommendations. BMJ, co-submission).

Methods

This study followed the MOOSE reporting guidelines (see online supplementary appendix 1). The registered study protocol is available online (PROSPERO: CRD42016041907).

bmjopen-2016-014327supp_appendix1.pdf (120.8KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

We included studies enrolling participants 18 years of age or older diagnosed with aortic stenosis that elicited values and preferences on outcomes related to treatment options for aortic stenosis, including SAVR or TAVI. We included studies reporting quantitative values and preferences regarding the decision of treatment, including studies on health state value, direct choice or forced choice, non-utility measurement of health states as well as qualitative studies that inform preferences, views, experiences, attitudes or perceptions. We considered patient values and preferences to be ‘the relative importance patients placed on the outcomes’ for the decision that they are considering. We excluded studies simultaneously addressing more than one disease if it did not provide information on aortic stenosis patients separately; studies reporting on treatment options for aortic stenosis before TAVI became available (2002); non-primary studies (eg, clinical practice guidelines, reviews, commentaries, communications, letters or viewpoints), case reports or case series; and studies reporting health-related quality of life of patients with severe aortic stenosis that did not elicit patients' values and preferences.

Search strategy

With the assistance of a research librarian, we searched MEDLINE, MEDLINE in-process, EMBASE and PsychINFO via Ovid, from 2002, using a combination of keywords and MeSH terms for ‘aortic stenosis’ AND ‘valve replacement’ and using the sensitive search filters on how stakeholders value health outcomes developed previously, which includes terms related to health utility, patient values, patient preferences and health-related quality of life (Selva-Olid A, Solà I, Zhang Y, et al. Development and use of a content search filter for studies on how patients and other stakeholders value health outcomes. Manuscript in progress 2016). We also searched for relevant abstracts from the Society of Medical Decision Making Annual Meetings (2005–2016) and Biennial Meetings (2011–2015), which were available online. The search strategy is available in the online supplementary appendix 2. For studies that were eligible, we reviewed their reference list to identify other potentially eligible citations. There were no language or publication status restrictions. We did not find any non-English studies, thus translators were not needed.

bmjopen-2016-014327supp_appendix2.pdf (124.9KB, pdf)

Study selection

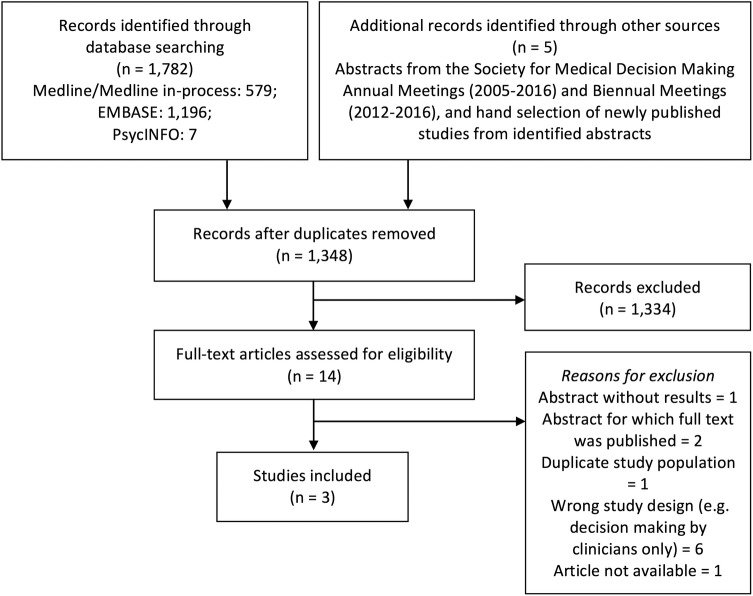

Three review authors (LL, RAS, VM) independently screened titles and abstracts using prespecified criteria, in pairs (figure 1). Two authors (LL, VM) independently reviewed full-text articles of potentially relevant studies. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and a third party was available when necessary (RAS, YZ).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Quality assessment

For observational studies addressing values and preferences that reported quantitative outcomes, we evaluated risk of bias using a novel instrument developed by Zhang et al, which includes the following domains: study population (sample selection, response rate), measurement accuracy (choice of the methodology, administration of the methodology, outcome presentation, understanding the methodology) and data analysis. We chose this instrument because there are no published tools for assessing risk of bias for values and preferences studies. For studies reporting qualitative outcomes, we used the CASP checklist to examine methodological limitations.13

Data collection and presentation

Two reviewers (LL, VM) independently extracted patient demographics (eg, age, sex), clinical characteristics (eg, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification), description of the methods used to elicit values and preferences and quantitative and qualitative results. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third party (RAS, YZ). We summarised results of quantitative and qualitative studies on values and preferences of outcomes of aortic stenosis management, with the focus on elucidating the relative importance associated with outcomes relevant to this condition. In addition, we reviewed the correlation between patients' values and preferences and their demographic (eg, age), clinical (eg, ejection fraction) or disease variables (eg, mental and physical health state, quality of life).

Incorporation into BMJ-RapidRecs

In the linked BMJ-RapidRecs project, a guideline panel of clinicians, researchers, methodologists and patient representatives (community panel members) create rapid and trustworthy recommendations, evidence summaries and decision aids for TAVI versus SAVR in low and intermediate risk patients (P O Vandvik et al. BMJ, co-submission). To provide the BMJ-RapidRecs guideline panel with best current evidence on treatment alternatives for all patient-important outcomes, three systematic reviews were conducted: on the relative effects of TAVI versus SAVR (R A Siemieniuk et al. BMJ, co-submitted), on prognosis (baseline risk from observational studies) (F Foroutan, G H Guyatt, K O'Brien, et al. Prognosis after surgical replacement with a bioprosthetic aortic valve in patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis: systematic review of observational studies. BMJ, co-submitted) and this review on values and preferences. Furthermore, the results of this review will be incorporated into the online consultation decision aids generated from the evidence summary supporting this BMJ-RapidRecs, available in an online authoring and publication platform MAGICapp (http://www.magicapp.org). The results will particularly inform the ‘practical issues’ section of the decision aids created for this guideline.14

Results

Of 1343 unique studies identified through database searching and 5 additional references through grey literature searching, 14 proceeded to full-text review, of which 2 full-text studies proved eligible15 16 (figure 1). One study published an additional article addressing the validity of the instrument they used (standard gamble), which we used to supplement the findings.17

Quantitative study

Using the standard gamble, Hussain et al15 17 evaluated the surgical mortality risk that patients were willing to accept if full health resulted from their surviving an AVR. The study was conducted in Norway from May 2010 to May 2015 and recruited consecutive patients with severe aortic stenosis referred to an outpatient clinic (Oslo University Hospital) for AVR. The 439 participating patients, of whom 40% were women (n=175), had a mean age of 75 years (SD 11). The median predicted mortality using the STS-PROM Score was 11.9% (IQR 7.5–17.1).

Regarding risk of bias, the authors enrolled a consecutive sample of patients, had a 98% response rate, used a verbal interview and visuals to represent the health state and instrument and analysed results appropriately. The authors did not, however, assess understanding of the standard gamble exercise by the participants. This raises the possibility that participants may not have understood the exercise, which could possibly explain what might be considered counterintuitive findings.

For the standard gamble, participants were given the hypothetical choice of continued life in their current health state or to undergo an intervention (SAVR) that either restores full health or results in sudden death. Participants were interviewed for ∼10 min and given a visual aid showing bars representing the risk of death. The interview began with patients being asked about symptoms of concern and to consider their physical and mental health, activity limitations, medications and treatment and any worries about their heath caused by aortic stenosis-related symptoms. Participants chose between continued life in their current health state and undergoing an intervention that either restores full health or results in sudden death. Full health was described as equal to that of an individual of similar age and sex without giving the number of years of life expectancy. The probability of death started at 95%. The probability of death was reduced by 5% intervals until the patient became indifferent between their continued health state and the gamble.

Risk willingness varied considerably among participants. The overall median risk willingness was 25% (IQR 25–50%); 130 participants (30%) were willing to accept low-to-intermediate mortality risk (≤8%), of whom 104 were unwilling to accept any risk of death; 224 (51%) high risk (>8–50%) and 85 (19%) a prohibitive risk (>50%), of whom 17 were willing to accept a probability of dying of 95–100%, which the authors attributed as placing an extremely low value on continued life in their current health. They used labels for risk categories of the AHA/ACC 2014 Guidelines, although almost 20% of the patients did not find a probability of over 50% prohibitive (ie, they were willing to accept this probability).7

The study also calculated correlations between demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as patient-reported measures of health, and risk willingness. Authors reported no relation between risk willingness and STS-PROM scores, age, sex, education level and medical history and depression symptoms. Patients with higher risk willingness had more severe echocardiographic valve findings, lower left ventricular ejection fraction, more severe functional impairment by NYHA functional classification (p<0.001), greater likelihood of having pulmonary disease (p=0.02), greater weekly restricting symptoms (p<0.001), worse Short Form-36 Item Health Survey Physical (p<0.001) and Mental Component function (p<0.01), worse EuroQoL 5-Dimensional health-related quality of life (p=0.001) and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) rated quality of life (p<0.001). In a multivariable logistic regression model examining risk willingness of >50% versus 50% or less, factors with a univariable p<0.25 were included; only the reported number of weekly restricting symptoms and EQ-VAS remained significantly associated with risk willingness over 50% (p<0.05).

Qualitative study

Lauck et al16 in a qualitative study conducted in a provincial cardiac TAVI centre in Vancouver, Canada, explored factors influencing the decision to be assessed for TAVI of 9 male and 6 female participants with a median age of 86 years (range 75–92) and a median perioperative risk by STS-PROM of 6.5% (range 2.6–16.3). The patients participated in interviews of ∼15–60 min; investigators transcribed and analysed the interviews for emerging themes. Six themes, each with three subcategories, emerged from their research: (1) symptom burden (shortness of breath, chest pain, increasing fatigue); (2) the ‘experienced’ patient (medical history, comparison with past significant medical experiences, ongoing medical management); (3) expectations (length of life, quality of life, risk and benefit analysis); (4) healthcare system and information support (source of experience, informal support system (family navigator), formal support system (physician navigator)); (5) logistical barriers and facilitators (financial resources, remote location and travel requirement, needing help) and (6) obligations and responsibilities (caregivers' responsibilities (for the patient and themselves), keeping house, being a partner).

Regarding the methodological limitations, the aim of the study was clear, the methodology chosen (exploratory qualitative approach) was useful to answer the research question and the data collection (semistructured interviews until informational redundancy) was appropriate. The authors conducted purposeful sampling and stopped data collection once they determined that informational redundancy was attained. Conflict of interest may have influenced that decision, as well as patient recruitment decisions: five of the nine authors are consultants for Edwards Lifesciences (a company that produces TAVI valves). The authors did not discuss the relationship between researcher and participant.

Discussion

Principal findings

Among patients referred for SAVR, patients manifested very wide variability in the probability of surgical mortality they were willing to accept to improve quality of life: substantial proportions of participants were willing to accept only low risk, intermediate risk or very high risk. High risk willingness was not associated with demographic characteristics but was significantly associated with greater functional and quality of life impairment. A number of such measures showed significance in univariable analyses, but for risk willingness of >50%, only the number of daily activities impaired, and the EQ5D-VAS remained significant in a multivariable model.

In 15 patients being considered for TAVI, investigators reported a number of factors that influenced their decision to have the assessment. Patients reported biomedical, functional, social and environmental considerations, including symptom burden, past experience, expectations of therapy, available support from the healthcare system and informal sources (eg, family), logistical barriers and facilitators and obligations and responsibilities.

Strengths and weaknesses

Our review has a number of strengths. First, we performed a comprehensive search of databases and grey literature and did not limit our findings to a particular study design. Second, we selected studies, extracted data and conducted risk of bias assessment independently and in duplicate. Third, for our risk of bias assessment, we used tools specific to each study design (CASP for qualitative studies and an instrument in the final stages of development for quantitative studies). Fourth, the study by Hussain et al met most criteria for low risk of bias. In particular, the quantitative study recruited consecutive patients and achieved a 98% response rate, enhancing the representativeness of the population. The qualitative study included patients of both sexes, with a relatively wide age range, and a wide range in risk scores.

There are several limitations, the most important of which is that we found only two full-text studies addressing the question of interest. Each study had inherent limitations regarding generalisability. The qualitative study recruited patients from a single tertiary care centre being assessed for TAVI only.16 The quantitative study recruited only surgical AVR patients from a tertiary care centre.15 Both studies included only high-risk patients.

Aside from issue of generalisability, limitations include Hussain et al’s use of only the standard gamble tool to address current perceptions of patients' quality of life. The instrument represents a specific, limited methodology that simplifies a complex decision process and raises questions of patients' understanding. Finally, the instrument used for assessment of risk of bias in the quantitative study is preliminary and still undergoing refinement and testing.

Context in relation to the body of literature

Findings of less risk aversion with progression of disease and poorer self-reported quality of life are consistent with studies of other conditions.18 19 For instance, in one study investigators found, using the standard gamble, that more severely affected patients ready for a transplant placed less value on their current health state than patients not ready for transplant.19 Similarly, another study reported lower standard gamble utility scores for patients with more debilitating health states, such as higher NYHA scores.18 Consistent with results from Hussain et al work, both studies highlighted important variation in individual values and preferences, regardless of health status measures and other correlates.

Our copublished and linked systematic review of treatment effects highlighted key trade-offs between risks and benefits with TAVI or SAVR (R A Siemieniuk et al. BMJ, co-submitted). Transfemoral TAVI reduces mortality, stroke, life-threatening bleeding, atrial fibrillation and recovery time at the cost of an increased risk of permanent pacemaker insertion, heart failure symptoms, short-term aortic valve re-intervention and serious uncertainty in long-term valve durability. The trade-off between risk and benefits needs to be considered in each individual circumstance.

Addressing the need for improved shared decision-making in surgery, investigators have developed an decision aid for high-risk surgeries.20 Consultation decision aids for patients at varying age and risk based on the evidence summary of the systematic review that informed the BMJ-RapidRecs are available online on the MAGICapp (http://www.magicapp.org), accessible through the BMJ-RapidRecs (P O Vandvik et al. BMJ, co-submission).

Unanswered questions and future research

There is a paucity of evidence addressing patient values and preferences on the management of severe aortic stenosis. Furthermore, based on the evidence available, variability in choice regardless of health state suggests that risk willingness is not always predicted by health status and disease burden, and thus when desirable and undesirable outcomes are closely balanced there is a need to engage in shared decision-making at the individual patient level. However, given the limited data available, the results of this review may not be generalisable.

Studies that follow-up patients throughout their actual decision process, optimally informed through shared decision-making, and in short term and long term after their intervention would provide additional useful information for clinicians and guideline developers. Investigators would usefully undertake research comparing values and preferences between all treatment options (SAVR, TAVI, medical treatment), using systematic and objective methods.

Conclusions

The finding of high variability in values and preferences suggests that guideline panels should issue strong recommendations only when benefits very clearly outweigh harms (or the reverse). When that is not the case, weak or conditional recommendations that mandate shared decision-making for the management of severe aortic stenosis are advisable. Further research addressing values and preferences of SAVR versus TAVI versus medical treatment would be useful to inform subsequent recommendations that are likely to be necessary in the face of evolving evidence of relative benefit and harm.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Amy Price for her review of the manuscript and valuable suggestions for improvement.

Footnotes

Contributors: LL led and coordinated the project. VM, RAS, YZ and POV involved in the conception and design of the review. LL, VM and RAS selected articles and extracted data. LL, VM, RAS, YZ, POV, TA and GHG involved in the interpretation and discussion of results. LL drafted the manuscript and all authors critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the article. LL is guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. YZ, GHG, TA, POV, LL and RAS are part of the GRADE working group. YZ is developing a risk of bias tool and GRADE evaluation for values and preferences studies.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Ross J, Braunwald E. Aortic stenosis. Circulation 1968;38(1 Suppl):61–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.38.1S5.V-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG et al. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: The Euro Heart Survey on Valvular Heart Disease. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1231–43. 10.1016/S0195-668X(03)00201-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osnabrugge RL, Mylotte D, Head SJ et al. Aortic stenosis in the elderly: disease prevalence and number of candidates for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a meta-analysis and modeling study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1002–12. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turina J, Hess O, Sepulcri F et al. Spontaneous course of aortic valve disease. Eur Heart J 1987;8:471–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Bash A et al. Percutaneous transcatheter implantation of an aortic valve prosthesis for calcific aortic stenosis first human case description. Circulation 2002;106:3006–8. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000047200.36165.B8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perera S, Wijesinghe N, Ly E et al. Outcomes of patients with untreated severe aortic stenosis in real-world practice. N Z Med J 2011;124:40.–. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:e57–e185. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2187–98. 10.1056/NEJMoa1103510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ et al. Transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1609–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa1514616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gargiulo G, Sannino A, Capodanno D et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation versus surgical aortic valve replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:334–44. 10.7326/M16-0060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alonso-Coello P, Montori VM, Díaz MG et al. Values and preferences for oral antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation: physician and patient perspectives. Health Expect 2015;18:2318–27. 10.1111/hex.12201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 2016;353:i2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.2014. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) CASP Checklists. Oxford: CASP. http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists.

- 14.Agoritsas T, Heen AF, Brandt L et al. Decision aids that really promote shared decision making: the pace quickens. BMJ 2015;350:g7624 10.1136/bmj.g7624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hussain AI, Garratt AM, Brunborg C et al. Eliciting patient risk willingness in clinical consultations as a means of improving decision-making of aortic valve replacement. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e002828 10.1161/JAHA.115.002828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lauck SB, Baumbusch J, Achtem L et al. Factors influencing the decision of older adults to be assessed for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: an exploratory study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs Published Online First: 23 Oct 2015. doi: 10.1177/1474515115612927 10.1177/1474515115612927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussain AI, Garratt AM, Beitnes JO et al. Validity of standard gamble utilities in patients referred for aortic valve replacement. Qual Life Res 2016;25:1703–12. 10.1007/s11136-015-1186-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis EF, Johnson PA, Johnson W et al. Preferences for quality of life or survival expressed by patients with heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 2001;20:1016–24. 10.1016/S1053-2498(01)00298-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singer LG, Theodore J, Gould MK. Validity of standard gamble utilities as measured by transplant readiness in lung transplant candidates. Med Decis Making 2003;23:435–40. 10.1177/0272989X03258421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steffens NM, Tucholka JL, Nabozny MJ et al. Engaging patients, health care professionals, and community members to improve preoperative decision making for older adults facing high-risk surgery. JAMA Surg Published Online First: 29 Jun 2016. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2016.1308 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014327supp_appendix1.pdf (120.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-014327supp_appendix2.pdf (124.9KB, pdf)