Abstract

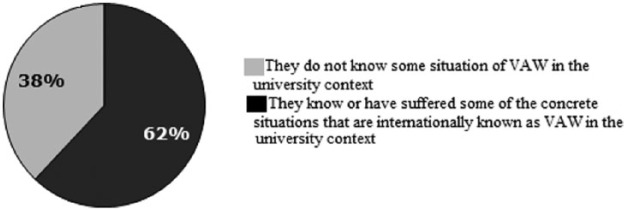

The first research conducted on violence against women in the university context in Spain reveals that 62% of the students know of or have experienced situations of this kind within the university institutions, but only 13% identify these situations in the first place. Two main interrelated aspects arise from the data analysis: not identifying and acknowledging violent situations, and the lack of reporting them. Policies and actions developed by Spanish universities need to be grounded in two goals: intransigence toward any kind of violence against women, and bystander intervention, support, and solidarity with the victims and with the people supporting the victims.

Keywords: violence against women, campuses, Spanish universities

Introduction

This article presents quantitative data on violence against women in Spanish universities. In particular, the results of the research project “Gender-Based Violence in Spanish Universities” (Valls, 2005-2008), which was funded by the government-run Spanish Women’s Institute, are reported. Although previous studies have explored the occurrence of violence against women in couples with university degrees and analyzed experiences of being victims of crime among university students, such as being the victim of thefts (Benítez & Rechea, 2008; Castellano, García, Lago, & Ramírez de Arellano, 1999), no research on violence against women conducted in the Spanish context has specifically addressed violence against women in Spanish universities.

The data presented here elucidate this reality as a first crucial step in taking action against, responding to, and preventing violence against women in the Spanish context. In doing so, first, we review several studies on this topic in different countries to provide a broader understanding of the phenomena and our study. We specifically investigate the circumstances and causes of violence against women in the university context and review current research in Spain related to this topic. Second, we present the methodology of the quantitative research project “Gender-Based Violence in Spanish Universities” (Valls, 2005-2008). We then present the main quantitative results, which is followed by a discussion. A section describing the study’s implications is also included to offer recommendations emerging from our findings. Finally, drawing from the results of our own investigation, we offer some final remarks and future research prospects related to this topic in Spain.

Violence Against Women in Universities

The literature review of international research on violence against women in universities has been organized into two sections: (a) an analysis of the different realities and causes of violence against women in universities worldwide, which primarily relies on literature from the United States because of its strong tradition of studying violence against women on college campuses, and (b) an analysis of research on violence against women in Spanish universities.

Realities and Causes of Violence Against Women in Universities Worldwide

Numerous incidents of aggression, rape, and abuse of authority occur in student dating experiences and in the diverse spaces of coexistence on college campuses (e.g., parties, fraternities, dorms). Studies of these issues are abundant, particularly in the United States, showing that violence against women on university campuses is common (Fisher, Daigle, & Cullen, 2010). Furthermore, such violence may take many different forms: abuse of authority, physical aggression, and unwanted sexual advances, among others. Gross, Winslett, Roberts, and Gohm (2006) reported that 27% of university women in their study (n = 935) had suffered some type of abuse or unwanted sexual situation since their enrollment in university, and more recent U.S. studies estimated that 20-25% of undergraduate women have suffered attempted or actual rape during their time at a university (Krebs et al., 2009; Vladutiu, Martin, & Macy, 2011). In the United Kingdom, an online survey conducted by the National Union of Students (2010) involving 2,058 female students showed that 68% had experienced some type of verbal or non-verbal harassment in or near their institution, 12% of respondents had been the victim of stalking, and 16% had experienced unwanted kissing, touching, or molestation.

As with various types of violence and violence against women in general, the aggressor in the university context is often a person whom the victim knows (Banyard et al., 2005; Bondurant, 2001; Forbes, Jobe, White, Bloesch, & Adams-Curtis, 2005). For instance, in a study of sexual aggression experienced by 109 university women, Bondurant (2001) found that only 6% of the perpetrators were strangers. In addition, violence against women in universities is perpetrated by not only peers (i.e., students) but also university professors (Garlick, 1994; Lee, Pomeroy, Yoo, & Rheinboldt, 2005). More alarming is that in some cases, the very institution has been identified as a perpetrator or accomplice of violence (Dziech & Weiner, 1990; Eyre, 2000; Fitzgerald et al., 1988; Grauerholz, Gottfried, Stohl, & Gabin, 1999). In this regard, perpetrators use institutional behaviors and practices to exercise different types of social control over women through physical force, coercion, abuse, or silencing. Moreover, sexual harassment and misogyny can be openly manifested in various forms of sexism that are present in academic curricula or in class discussions and debates. Meanwhile, women’s resistance to accepting patriarchal structures or subordination to men in universities has triggered adverse and even hostile reactions.

Research has already identified a variety of reasons for the existence and perpetuation of violence against women in the university context. However, we have identified four particular causes of violence against women that are specifically relevant in this context: the existence of power structures placing men over women, the presence of hostility toward victims, the naturalization and tolerance of violence, and the presence of sexist stereotypes.

The existence of power structures placing men over women and the power of professors over students has fostered violence against women for many years and has increased the vulnerability of women (Dziech & Weiner, 1990; Eyre, 2000; Grauerholz et al., 1999; Mahlstedt & Welsh, 2005; Reilly, Lott, & Gallogly, 1986). In her analysis of campus institutional responses to peer sexual violence, Cantalupo (2012) identified nine types of institutional responses that reflect deliberate indifference to reports of sexual violence, including taking no action at all; recommending that the victim not report the incident to anyone else, including her parents and the police; and waiting to investigate the report or investigating the report so slowly that it takes months or years for the survivor to receive any redress. Because of institutional responses such as these, many victims often remain silent for fear of not being taken seriously or not receiving any support from the university institution (Choate, 2003); thus, many victims tell only their friends or classmates about the violent situations that they experience and do not report the incident further (Orchowski & Gidycz, 2012; Paul et al., 2013).

Permissive dynamics with respect to violence contribute to the creation of a context of hostility, which has led some victims to even blame themselves for having provoked such situations (Gross et al., 2006; Schwartz & Leggett, 1999) or has made them feel isolated and marginalized by their peers (Stombler, 1994).

Some women can contribute to perpetuating violence by supporting the discourse of victim blaming. In Cowan’s (2000) study of rape, participants in the sample of 155 university women provided the following responses: “the victims provoke the situation,” “rape is only performed by men with mental pathologies,” and “men who rape cannot avoid it because of their sexual needs.” The author analyzed the rejection, lack of solidarity, and mistrust among the women and concluded that such attitudes are not isolated. She further noted that these attitudes must be understood in the context in which this set of social beliefs prevails. These social beliefs result from socialization fostering tolerance of violence and sexual harassment, legitimating the creation of a hostile atmosphere toward women.

Other explanations for the presence of violence on college campuses are related to the naturalization of violence in relationships and the characterization of violence as only involving physical aggression. For example, to constitute rape, the perpetrator must have completed a sexual act with penetration, and the victim must have suffered physical violence at the hands of the perpetrator (Gross et al., 2006). Furthermore, some beliefs related to sexual stereotypes contribute to the prevalence of misconceptions regarding violence against women, victim blaming, and sexist and racist values within society (Burt, 1980; Fonow, Richardson, & Wemmerus, 1992).

Research has shown that sexist dynamics created in some U.S. fraternities and British colleges substantially influence beliefs and attitudes among some university men toward women. Thus, a correlation exists between the acceptance of rape myths by men and violence against women. Simultaneously, membership in one of these male organizations can foster sexist behavior, as extreme models of traditional masculinity or hyper-masculinity related to the normalization and permissiveness of violent behaviors and sexual aggression toward women (Boeringer, 1999) are promoted in many fraternities (Robinson, Gibson-Beverly, & Schwartz, 2004). By contrast, other researchers have noted that not all men who belong to fraternities develop negative attitudes toward women and that pejorative behavior toward women is not promoted in many fraternities (Banyard et al., 2005; Boswell & Spade, 1996). Thus, the development of sexist and violent attitudes toward women is not directly related to fraternities themselves but is related to the existence of certain behavioral patterns and regulative norms regarding social relations between men and women that favor an atmosphere of violence and sexual aggression (Choate, 2003; DeKeseredy, Schwartz, & Alvi, 2000; Eyre, 2000; Flecha, Puigvert, & Ríos, 2013; Gómez, Munté, & Sordé, 2014).

All these elements affect responses to violence from both victims and the overall community, particularly with regard to the identification and reporting of violence. Nevertheless, awareness and knowledge of incidents that constitute violence vary widely. For instance, not all members of university communities consider incidents such as unwanted kissing and touching or sexual relations without consent to be perpetrations of violence (Belknap, Fisher, & Cullen, 1999; Kalof, Eby, Matheson, & Kroska, 2001; Reilly, Lott, Caldwell, & DeLuca, 1992; Shepela & Levesque, 1998). Similarly, research has presented cases in which girls have been forced to enter into sexual relations without their awareness. Regarding stalking, Fisher et al. (2010) reported that 83.1% of the incidents identified in their study were not reported to the police or campus authorities. Often, victims who do not recognize that they have suffered violence are more reluctant to report their experiences. Victims’ failure to report violence in the university context is nevertheless correlated with not only a lack of recognition of violence against women in universities but also the causes of violence against women described above, such as a hostile atmosphere against women.

Violence against women in universities has also been found to have damaging effects on victims. These effects range from declining academic performance to the need to modify or even abandon previous academic and professional choices (Bondurant, 2001; Dziech & Weiner, 1990; Fitzgerald et al., 1988; Marks & Nelson, 1993). For instance, some women stop attending classes to avoid their aggressors, change colleges or universities, or change residences (Fisher et al., 2010).

Research on Violence Against Women in Spanish Universities

The results of research conducted in Spain are consistent with many of the findings reviewed above. The lack of support for victims and the difficulty of identifying violent situations present challenges in both the international and Spanish contexts. However, important differences between Spanish university campuses and university campuses in other countries exacerbate the problem of violence against women in Spanish universities. For instance, unlike universities in the United States and other European countries, Spanish universities provide little university housing for students. Students may continue living with their families when they enter university, and emancipated students may live in different parts of a city rather than one specific area. In addition, although student associations similarly represent different governing bodies of universities, fraternities or sororities do not exist.

Furthermore, because of the different settings for student interaction in Spanish universities, on-campus parties are less frequent on Spanish campuses than on U.S. campuses. On some occasions, students organize parties for fundraising, but these events are usually held in discotheques rather than on campus. In addition, these parties are usually open to everyone—both the university community and outsiders.

Regarding university positioning on violence against women, we also find important differences between Spain and countries with stronger traditions of research and action related to violence against women. In these countries, the myth that violence against women does not occur in universities was refuted back in the 1990s, and consequently, laws preventing violence against women were passed (Renzetti & Edleson, 2008). However, similar action did not occur simultaneously in Spain. In Spain, social awareness of violence against women has nevertheless steadily increased (Roggeband, 2012), reaching an important point in 2004, when the issue became an item on the political agenda with passage of the Organic Law on Integral Protection Measures Against Gender Violence (Spanish Government, 2004), the first law pertaining to violence against women in Europe. Nonetheless, unlike similar laws in other countries, such as the United States, the Organic Law did not specifically mention universities as spaces where violence against women can occur.

Although the Organic Law did not mention this possibility, some scholars in Spain were committed to reporting complaints of university students and professors regarding violence against women in universities, with the ultimate goal to end this type of violence. For example, in 2004, a conference titled “Violence Against Women: Who, for What and How to Overcome It” was held in Barcelona and was attended by one of the members of the Spanish parliament who had previously been part of the commission in charge of elaborating the project of the above-mentioned Organic Law. This conference showed how violence against women in universities had been ignored in Spain and how there had been a “law of silence” that both contributed to and legitimized the perpetuation of violence against women. The main discussion pertained to the need to create specific offices with protocols against sexual harassment based on the practices of universities that were considered the most effective in this regard worldwide. This discussion truly surprised the attending member of Spanish parliament, who committed to ensuring that future legislation includes the creation of equality units and protocols against sexual harassment as a mandatory requirement for Spanish universities to address and prevent violence against women in the university context. Three years later, the Law for the Effective Equality Between Women and Men was passed (Spanish Government, 2007). This law covers aspects related to gender inequality and finally addresses the issue of violence against women, recommending actions to not only overcome violence against women but also prevent it in public institutions (including state universities). Article 48 of the law requires companies to create specific measures to prevent sexual harassment in the workplace, stipulating the establishment of procedures to facilitate reporting of harassment by victims and an obligation of worker representatives to report to the head of a company any harassment of which they are aware. In addition, Article 62 of the law requires the development of protocols to prevent sexual harassment by companies, which must stipulate the need to investigate complaints and must clearly identify the person who is responsible for assisting victims. Despite the concrete progress that this law envisaged in terms of measures designed to act on and prevent sexual harassment, Spanish universities have largely ignored the law because of their continued lack of acknowledgment for the existence of violence against women in their institutions. Hence, the measures established by the Law for the Effective Equality Between Women and Men, such as the development of specific protocols against sexual harassment by commissions of equality, have not been implemented in most Spanish universities (García-Lastra, & Díaz-Díaz, 2013). In 2010, among the 45 universities that participated in a study conducted by the Isonomia Foundation (2010), 36 universities had a unit or office of equality, and four universities were in the process of creating such a unit or office. Among the 36 universities with a unit or office of equality, only 11 considered violence against women among their strategic axes in general or, more specifically, considered issues related to sexual harassment, sexist attitudes, and perceptions of discrimination. Hence, 3 years after the Law for the Effective Equality Between Women and Men was passed, 34 of 45 universities had not complied with the law with regard to addressing violence against women. More recent research has analyzed whether Spanish universities comply with all the legal requirements within the Organic Law on Integral Protection Measures Against Gender Violence (Spanish Government, 2004) and, more specifically, Article 7, which mandates that all universities include specific units on gender equality in their teacher education programs (including professional education). In this regard, Puigvert (2007-2010) reported that universities have not been successfully integrating such units and that they have therefore not been meeting the legal standards imposed by the Organic Law on Integral Protection Measures Against Gender Violence.

Method

Participants

The sample was drawn from an infinite population and comprised 1,083 university students from six universities from different regions in Spain (Andalusia, Castile and León, Catalonia, Valencia, Murcia, and the Basque Country). To select the participants, we used a multistage sampling technique. During the first stage, we selected six Spanish universities to account for the diverse characteristics of Spanish universities, which differed in size in terms of number of students enrolled (with three large universities having 50,000-60,000 students and three small universities with fewer than 30,000 registered students) and in geographic setting. The quantitative fieldwork consisted of a survey distributed among a representative sample of 1,083 university students, calculated with a margin of error of ±2.97% and a 95% confidence interval. The sample was stratified according to gender, knowledge area (humanities, experimental sciences, social and juridical sciences, technical studies, and health sciences), and type of degree (3-year associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, and doctorate degree). Among the total respondents, 67% were women, 33% were men, and the mean age was 23 years. Undergraduate students accounted for 94% of the interviewees, and 6% were graduate students (master’s and PhD candidates).

The quantitative fieldwork aimed to provide insight into existing incidents of violence against women in Spanish universities and reactions to such violence from the perspective of victims and the broader university community. The quantitative data were complemented with qualitative fieldwork to explore university community members’ interpretations of incidents of violence against women in their universities and institutional responses to such violence. The present article focuses on the quantitative results of the study.

Instrument

The survey included 85 questions organized into five themes (see the appendix). The variables and questions were designed based on an extensive review of the literature and previous surveys of violence against women in universities (Banyard et al., 2005; Fisher, Cullen, & Turner, 1999; Gross et al., 2006; Kalof et al., 2001). The questions in the survey pertained to eight types of violence that were identified based on the above-mentioned investigations. These types of violence centered on a more concrete definition of violence against women, which was more detailed than the definition1 given in the Organic Law on Integral Protection Measures Against Gender Violence (Spanish Government, 2004). Nonetheless, as this study is the first research on violence against women in Spain, we did not focus on one specific type of violence or one particular circumstance; rather, we sought to provide an overview of the general reality of violence against students in Spanish universities.

Procedure

The following strategies were used to select students for the study sample. The researchers visited the different universities and stayed in a room for 2-4 hr. Prior to these visits, signs informing students about the study and offering them the opportunity to participate by visiting a specific location where the survey was being administered were distributed in classrooms, cafeterias, and residence halls. In some cases, we sought assistance from the administration offices to distribute the questionnaire. Personnel in these administration offices sent an email to all professors informing them about the research and the day and hour when the surveys would be conducted. In some cases, we also sought assistance from professors who were not linked to the project and from student associations in distributing the questionnaire. After the universities were selected, a quota of survey respondents was established according to gender, knowledge area, and type of degree.

An information sheet for participants and a protocol for the survey process were designed. The information sheet informed participants of the research objectives and the commitment of the researchers to maintaining the anonymity of the participants and to using the data gathered to prevent violence against women in Spanish universities. Presenting the research objectives, which were also recalled by the researcher when responding to the survey, was particularly important to ensure that the participants were considering only violence against women rather than other types of violence and only violence occurring in the university context. The information sheet also specified the voluntary nature of participation, and the participating students were asked to be honest in their responses to the questions and to consider the social responsibility attached to the research results. The document also provided a contact address so that the students could request more information about the research and the topic in general. These aspects made the entire process of study participation transformative for some students, as it required them to reflect on the situations that they were in and that they knew about and even to search for ways to address these situations.

The protocol for the researchers who were responsible for collecting the data aimed to ensure that the survey was administered in optimal conditions following criteria that guaranteed scientific rigor and confidentiality. Specifically, the protocol ensured that (a) the survey was distributed to groups of 30 or fewer students, (b) only the participants completing the survey and one member of the research team were present in the room, and (c) every survey was distributed and collected in an envelope to ensure anonymity. Furthermore, the protocol urged the researchers to guarantee confidentiality verbally and to ask students to be honest in responding to the questions and to focus on the topic of violence against women in the university context.

Data Analysis

We conducted a descriptive univariate analysis of the quantitative data collected from the surveys. The analysis aimed to identify the existence and types of violence against women in Spanish universities, with a focus on five aspects: data on socio-demographic characteristics, the acknowledgment of violence against women, situations of violence against women in the Spanish university context, reactions of victims, and the existing resources and measures implemented to prevent and overcome violence against women in universities. In view of the scientific knowledge that we contribute here, which primarily aims to elucidate the reality of violence against women in Spanish universities, future research should take one step further and determine how to address situations of violence against women in Spanish universities and how to overcome barriers to preventing and overcoming such violence.

Results

Violence Against Women: A Hidden Reality in Spanish Universities

The study participants associated violence involving physical and/or sexual aggression with violence against women; however, behaviors involving control, domination, and humiliation were not associated with violence against women. For instance, 23% of the students did not regard the act of preventing girls from talking with other people to be a form of violence, and 26% of the students did not consider unpleasant comments regarding women’s physical appearance to constitute violence.

Table 1 presents the list of potentially violent situations together with the corresponding percentage of students participating in the survey who did not consider these situations to constitute violence toward women.

Table 1.

Situations of Violence Against Women That Spanish University Students Did Not Recognize as Violence.

| Situations that can occur in a relationship (whether stable or sporadic) | Percentage of students who did not view the situation as violence against women |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 1,083) | Women (n = 726) | Men (n = 357) | |

| 1. Insults you | 14 | 13 | 16 |

| 2. Prevents you from talking to other people | 23 | 18 | 32 |

| 3. Criticizes or discredits what you do | 27 | 21 | 39 |

| 4. Makes unpleasant remarks about your physical appearance | 26 | 21 | 36 |

| 5. Demands a way of dressing, styling, and behaving in public | 21 | 16 | 32 |

| 6. Demands to know whom you are with and where | 33 | 29 | 42 |

| 7. Throws things at you, grabs you, or pushes you violently | 4 | 3 | 6 |

| 8. Hits you or commits other physical brutalities on you | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| 9. Uses force to have sexual relations with you | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| 10. Systematically despises you | 14 | 12 | 18 |

| 11. Intimidates and threatens you | 5 | 4 | 8 |

| 12. Touches you or places his hands on you in different intimate parts of your body against your will or corners you to touch or kiss you | 6 | 5 | 9 |

| 13. Follows you persistently | 20 | 18 | 24 |

| 14. Makes spiteful calls, emails, letters, or notes insisting on having a relationship with you | 25 | 22 | 31 |

The analysis of the results by gender showed that women were able to identify situations of violence against women more often than men. Approximately 56% of the women considered all the situations listed in this table to constitute violence against women, whereas only 42% of the men did so. In addition, the difference between the number of women and the number of men who viewed Situations 2-6 (Table 1) to constitute violence against women was greater than 10%, with a greater number of women than men identifying such situations as violence against women.

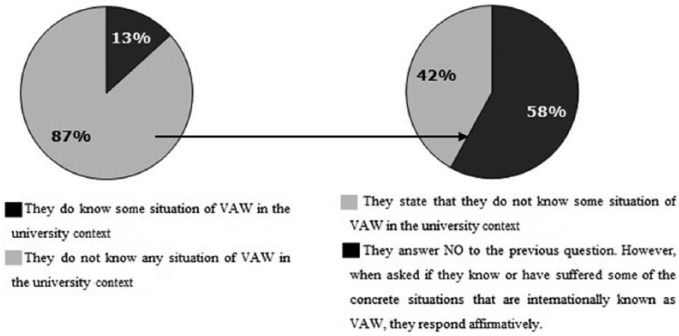

This difficulty in identifying situations of violence against women was clearly observed in the contradicting answers provided by more than half of the students surveyed when they were asked to recount instances of violence against women in their university. First, the researchers asked whether the students knew of any situation of violence against women that had occurred at their university or between people from the university community; only 13% (n = 142) provided an affirmative answer. However, when the students were provided with a particular list of situations—physical aggression; psychological violence; sexual aggression; pressure to a have sexual or emotional relationships; non-consensual kissing or touching; discomfort or fear of remarks, looks, emails, phone calls, persecution, or surveillance; dissemination of rumors about one’s sexual life; sexist remarks on the intellectual capacity of women or their role in society or remarks with hateful or humiliating sexual connotations—58% (n = 531) of the students who had answered “no” to this question later affirmed that they had experienced or knew someone who had experienced at least one of these situations in the university context (see Figure 1). Thus, combining the results of these two questions, the percentage of our study participants who had experienced situations of violence against women at their universities or between people belonging to the university community increased from 13-62% (n = 673) when the question provided descriptions of specific situations (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Students who do not recognize violence against women the first time they are asked.

Note. VAW = violence against women.

Figure 2.

Students who are aware of or who have experienced violence against women in Spanish universities.

Note. VAW = violence against women.

Table 2 shows the percentage of students who recognize that they have suffered or who know someone who has suffered some of the given situations involving violence against women. Among the students (n = 673) who have experienced or who know someone in the university context who has experienced some of the situations listed in Table 2, 24% of these students had been at the university for less than 2 years. Forty-nine percent of the respondents indicated that they have experienced or that they know persons who have suffered more than one type of violence against women in the university domain. In the great majority of the cases (84%) known by the students, the victim (who could be either a female or male student or university professor) was a female student (92%). Regarding the aggressors, the most common profile was a man (84%) and a student (65%). In addition, remarkably, 25% of the persons who had known about or witnessed violence against women stated that the aggressor was a professor. Furthermore, only 16% of the participants stated that the aggressor was unknown to the victim.

Table 2.

Violence Against Women in the Spanish University Context.

| Have you or anyone you know from the university ever suffered from these situations (in the university context)? | |

|---|---|

| 1. Physical aggression | 7% |

| 2. Psychological violence | 20% |

| 3. Sexual aggression | 2% |

| 4. Pressure to have a sexual or emotional relationship | 6% |

| 5. Kissing and/or touching without consent | 7% |

| 6. Discomfort or fear of remarks, looks, emails, notes, or phone calls, persecution or surveillance | 15% |

| 7. Dissemination of rumors about one’s sexual life | 16% |

| 8. Sexist remarks on the intellectual capacity of women or their role in society or remarks with hateful or humiliating sexual connotations | 42% |

How Do Victims and Universities React to Cases of Violence?

Regarding the reactions of victims to situations of violence, 91% of victims decided not to report the incident, but among these students, 66% did tell someone about the incident. One of the possible reasons that victims do not report incidents of violence is that victims generally do not regard themselves as victims of violence against women (64%), reflecting this study’s finding that many situations of violence against women are not recognized as violence against women. Nonetheless, other reasons exist for not reporting violence against women. In the survey, 92% of the students stated that they did not know whether a service existed for victims at the university. Moreover, 85% of the students stated that universities should provide services for people who suffer any type of violence against women. Students regard such services as crucial for determining how to respond when facing violence against women in the university. Feeling unsupported by the institution constituted an additional reason explaining the lack of reporting of violence against women. Among people who dared to report a situation of violence against women in the university context, 27% did not feel that the institution supported them, and 69% of the respondents felt uncertain as to whether victims would be supported by the university.

Discussion

The results provide evidence that violence against women occurs within Spanish universities, as in other universities and other institutional contexts around the world. This violence does follow certain patterns that are similar to those described in the studies reviewed above; for instance, in most cases, the victims are women and students, and most aggressors are men. Two main interrelated aspects arise from our data analysis: the failure to identify and acknowledge violent situations and the failure to report them.

Thus, our study elucidates the reality that students often do not recognize particular situations as violent, even when they are generally or legally recognized as such. This finding is important, as our results are consistent with other studies warning about the possible imbalances that can occur from differences between the definition of violence assumed by victims and legally established definition of violence. In Amar’s (2007) research, 32% of the victims identified themselves as having experienced stalking, but this number decreased to 26% when a legal definition was used. In our case, other elements were identified to limit the identification and reporting of violence against women in universities and other social spheres. One of those limitations relates to the definition (see Note 1) of violence adopted in 2004 by the law on Integral Protection Measures Against Gender Violence (Spanish Government, 2004), which limits the profile of perpetrators exclusively to individuals who are or have been the victim’s spouse or boyfriend. This limited definition, which has been widely criticized, was subsequently corrected in other separate legislation on this matter, but it remains in force at the national level. Other limitations of the same Spanish law include a failure to specify the actions that constitute violence against women and the domains in which they can occur. Specifying such aspects would help both facilitate the identification of cases and inform policies and, ultimately, specific measures (Banyard, Plante, & Moynihan, 2004; Bondurant, 2001; Fisher et al., 2010).

In addition, the qualitative data collected in this study (via in-depth interviews and communicative daily life stories) corroborate some of the reasons underlying the failure to recognize violent situations: the permissive dynamics with respect to violence, the naturalization of violence, and the high level of tolerance of violence. The results of the study are consistent with various cases reported in the media, perceptions expressed by members of the university community in various forums (such as the final conference for this research project), and the open answers written by the students themselves in the surveys, in which the students reported specific cases of violence occurring in their institution. Thus, as expressed in their comments, the students were grateful for the research being conducted on this topic to have an opportunity to address the numerous cases of violence against women occurring in their daily lives at their universities.

The specific structure of Spanish universities must be considered when analyzing the reasons for the failure to report violence against women (a level that reached 91% in our investigation). Our finding that the affected individuals did not regard themselves as victims of violence is only one of the reasons for the failure to report such cases. As other studies have shown, reporting violent situations in universities may be futile without appropriate follow-up action and clear institutional positioning on violence against women (Vidu, Schubert, Muñoz, & Duque, 2014). Universities oftentimes do not want to recognize violence against women as a problem and tend to remain silent about it, creating an environment that supports those in authority rather than victims and/or individuals who decide to report such incidents (Puigvert, 2008). Such an environment creates an atmosphere that is hostile toward victims and permissive of violence. As previous investigations have shown, in addition to the lack of knowledge about violence, institutions’ public stance on violence also plays an important role. In our investigation, the lack of support experienced by 27% of the victims who reported their case to their university was clearly a barrier to the creation of conditions in which victims can denounce such actions or encourage other students to report cases of violence to the university.

Thus, according to our analysis, the first step in overcoming violence against women in Spanish universities is convincing college women of the necessity of reporting stalking, sexual harassment, and other manifestations of violence against women either to campus authorities or to trusted friends. However, such efforts must also account for other reasons that cases of violence against women are not reported, such as the structure of Spanish universities and the hostile environment toward victims that has been created.

This recommendation is logical given the current context of Spanish universities. With regard to violence against women, Spanish higher education is regulated by various general laws, such as the Spanish criminal code and the Organic Law on Integral Protection Measures Against Gender Violence (Spanish Government, 2004); however, in contrast to most universities in other countries, Spanish universities are not regulated by laws specific to the university context. Despite some recent changes that have been introduced in this regard, we still found cases in which institutions have acted with deliberate indifference toward reports of violence against women among the few universities in Spain that now have protocols of action and response, as Cantalupo (2012) noted in the U.S. context. This finding was a major result emerging from the survey when the issue of violence was specifically made visible and discussed.

Notably, the results of our study served as the basis for a protocol designed by one of the project’s researchers,2 who was a member of the Equality Committee of the School of Economy and Business at the University of Barcelona. The first protocol for the prevention of and response to violence against women was approved on November 4, 2011. Subsequently, different Spanish universities’ equality units have begun to implement similar institutional processes with the support and advice offered by this research team.

Further Implications of the Study

Drawing on our analysis and other research, we have found that Spanish universities face an urgent need to develop policies and actions to address violence against women. From our findings, we have identified two goals—based on the lines of action already identified by the scientific community—in which policies and actions should be grounded: (a) absolute intolerance toward any type of violence against women, and (b) bystander intervention and support for and solidarity with victims and people supporting victims. These measures will help eradicate the permissive attitude toward violence, better identify different violent situations, and facilitate complaints and action in cases of violence against women, whether on the part of the victims or on their behalf by others in their environment.

Absolute Intolerance Toward Any Type of Violence Against Women

Overcoming violence against women within the university context requires institutions to publicly commit to maintaining zero tolerance for any type of aggression. Such a commitment requires the people in a university and the university as an institution to actively work together within the university community to encourage the reporting and rejection of all types of violence (Bryant & Spencer, 2003; Nicholson et al., 1998). To achieve this goal, among other actions that have already been performed, the following must also be implemented: training programs; disciplinary codes and programs for the prevention and awareness of on-campus violence against women; discussion of the topic of violence against women within all spaces where misogyny may appear, such as academic curricula or debates in the classroom; measures for handling situations in which a member of a university community who perpetrates violence or harassment against women or against people provides false testimony.

Bystander Intervention and Support for and Solidarity With Victims and People Supporting Victims

The perception of the university as an unfavorable environment for women characterized by victim blaming and little solidarity with women fosters passivity among students and discourages victims and other persons from reporting cases of violence and seeking assistance. To overcome the problem of violence against women, spaces for support, assistance, and solidarity must be created within universities to help victims. Furthermore, recent programs, such as Green Dot (Coker et al., 2011), highlight the importance of not only supporting a victim when she decides to report an incident but also promoting bystander intervention (Banyard et al., 2004; McMahon & Banyard, 2012; Moynihan, Banyard, Arnold, Eckstein, & Stapleton, 2011; Oliver, Soler, & Flecha, 2009; Shorey et al., 2012).

Conclusion

The results of this investigation present scientific evidence regarding the violence that occurs in Spanish universities. Overall, the results indicate that violence against women in Spanish universities shares several characteristics with the violence that occurs in universities in other countries. Although the investigation provides data showing that violence against women occurs in Spanish universities, the results also indicate that students have difficulty identifying situations as constituting violence. Moreover, barriers exist that hinder the reporting of violence, and future investigations should study these barriers in depth. University students generally lack knowledge of the resources and measures related to violence against women that universities offer, and in the majority of Spanish universities, these resources are either poor or non-existent. Unfortunately, when victims approach a university institution to report their case, few students feel welcome to do so by their institution.

Universities are encouraged to respond to violence in every country, including Spain, where this problem has only recently been acknowledged. Regarding violence against women, Spanish universities should follow the indications provided in various general laws, such as the Spanish criminal code, the Organic Law on Integral Protection Measures Against Gender Violence (Spanish Government, 2004), and the Law for the Effective Equality Between Women and Men (Spanish Government, 2007). The results of our investigation and subsequent studies (Vidu et al., 2014) confirm that Spanish universities tend not to intervene in situations of violence against women and that they simply delegate the responsibility to take actions to other institutions, such as the police. However, such a response is insufficient to address the problem of violence against women in universities. Research shows that the universities that are most effectively addressing violence against women have implemented policies and measures that are specifically designed to address this problem and that the governments in these countries have approved specific laws addressing violence against women at universities. Such policies promote greater identification of violence by victims in universities, facilitate reporting by the affected women, dissuade aggressors from perpetrating violence, and foster greater involvement of the community in helping the victims. Because of these achievements, these institutions are reducing violence against women on their campuses and making their universities safer places.

In view of the results presented here, future research should thoroughly explore the causes of violence against women, particularly those related to the particularities of the Spanish context (i.e., the Spanish university structure and the dynamics of university life in Spain). These characteristics of Spanish universities should shape policies and measures for the prevention of and response to violence against women in Spanish universities. Moreover, future investigations should more thoroughly analyze the different types of violence against women in Spanish universities. A research study that exclusively focuses on one type of violence against women could elucidate the circumstances in which this violence occurs and the particular characteristics of victims and aggressors, among other aspects. For instance, in the case of stalking, research could determine the definition that Spanish students apply to stalking in order to clarify whether they view stalking as a repeated behavior, as unwanted by the victim, and as an action that produces fear or emotional discomfort or that implies a credible threat, among other perceptions (Renzetti & Edleson, 2008). The results of the present research also suggest that many students have difficulty identifying incidents of aggression as incidents of violence against women. Thus, future studies could analyze the extent to which the dynamics promoted by Spanish universities facilitate access to knowledge about violent situations, enhancing students’ ability to identify violence against women, or promote a permissive attitude toward violence against women (in which case, the universities could be considered accomplices).

The recent open debate on violence against women in Spanish universities, the media attention on the present study, and the theoretical framework have allowed us to reveal situations of violence against women in Spanish universities. Moreover, based on these findings, we have been able to identify evidence-based actions that can be used to address the issue of violence against women in Spanish universities and to open a new era fostering the development of prevention and response measures. For Spain, the knowledge that is shared here and that can be gained from future research is fundamental to ensure that more women in the university community take action to eradicate violence against women in universities and find themselves in a context that supports them in denouncing such violence. Thus, advances can be made to protect the right of every woman to have academic experiences free of violence in universities.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Jesús Gómez and Ramón Flecha for initiating the struggle against gender violence at Spanish universities and for never giving up despite the harassment and attacks they received.

Author Biographies

Rosa Valls, PhD, is professor in social pedagogy at the University of Barcelona, and member of CREA (Community of Research on Excellence for All) Women’s Group Sappho. She was the main researcher of the first study about violence against women in Spanish universities, funded by the Spanish Women’s Institute. For more than 30 years, she has been involved in feminist struggles for overcoming gender inequalities in Spain. She is also a member of Roma Association of Women Drom Kotar Mestipen.

Lídia Puigvert, PhD, is Marie Curie Fellow, Institute of Criminology, University of Cambridge; and professor of sociology at the University of Barcelona, and member of CREA (Community of Research on Excellence for All) Women’s Group Sappho. Her work has focused on the development of dialogic feminism and the preventive socialization of gender violence. In 2008, she was a member of the Advisory Board to the European Policy Action Centre on Violence Against Women at the European Women’s Lobby.

Patricia Melgar, PhD, is tenure-track lecturer in education at the University of Girona, and member of CREA (Community of Research on Excellence for All) Women’s Group Sappho. She has been involved in several studies on overcoming violence against women. Her doctoral thesis explored how female victims of violence overcome abusive affective–sexual relationships. She is the secretary of the Catalan Platform Against Gender Violence that includes 110 institutions and nongovernmental organizations.

Carme Garcia-Yeste, PhD, is professor in education at the University Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, and member of CREA (Community of Research on Excellence for All) Women’s Group Sappho. Her work has focused on the study of Schools as Learning Communities, which has been recommended by the European Parliament to prevent early school leaving. Her research analyzes how these schools constitute an effective model for engaging the grassroots community of women in the processes of preventing and combating gender violence in education.

Appendix

Topic Sections of the Survey

Socio-demographic questions: These questions aimed to record participants’ age, place of birth, marital status, cohabitation status, employment status, and university where they study.

Recognition of violence against women: These questions aimed to determine participants’ level of recognition of violence against women through the introduction of various situations, such as insults; offensiveness; humiliating references to physical appearance; demands regarding one’s way of dressing, hairstyle, and behavior in public; and requests to know whom you are with and where you are.

Situations of violence against women: In this section, the questions pertained to the identification of the victim and the perpetrator as well as the place where an act of violence against women has occurred. Regarding each of the different situations identified as violence against women by the international research, we asked for the gender of the victim and the perpetrator as well as their position within the university.

Victim’s reaction: In this section, the questions pertained to the identification of situations of violence against women by the victim and their reaction after having such an experience. In this section, we also asked two more questions: whether the victim felt supported by the university in reporting the situation and whether she or he explained what had occurred to anyone else, followed by the profile of the person (e.g., a friend, a family member, a university staff member).

Resources and measures available at the universities: This final section asked the participants about available resources at the universities, both to assist victims of violence against women and to perform preventive actions.

Article 1.3 states that “the gender violence to which this Act refers encompasses all acts of physical and psychological violence, including offenses against sexual liberty, threats, coercion and the arbitrary deprivation of liberty” (Spanish Government, 2004).

Marta Soler Gallart, professor of Sociology at the University of Barcelona and director of Center of Research in Theories and Practices that Overcome Inequalities.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This article is an elaboration of one part of the research Gender-Based Violence in Spanish Universities (Valls, 2005-2008) funded by the Spanish Women’s Institute—Ministry of Work and Social Affairs, Spanish Government. Rosa Valls was principal investigator.

References

- Amar A. F. (2007). Behaviors that college women label as stalking or harassment. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 13, 210-220. [Google Scholar]

- Banyard V. L., Plante E. G., Cohn E. S., Moorhead C., Ward S., Walsh W. (2005). Revisiting unwanted sexual experiences on campus: A 12-year follow-up. Violence Against Women, 11, 426-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard V. L., Plante E. G., Moynihan M. M. (2004). Bystander education: Bringing a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention. Journal of Community Psychology, 32, 61-79. [Google Scholar]

- Belknap J., Fisher B. S., Cullen F. T. (1999). The development of a comprehensive measure of the sexual victimization of college women. Violence Against Women, 5, 185-214. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez M. J., Rechea C. (2008). Encuesta de victimación a estudiantes de Castilla-La Mancha: Un estudio piloto [Victimization survey to students from Castilla-La Mancha: A pilot study]. In. Rechea C., Bartolomé R., Benítez M. J. (Eds.), Estudios de criminología III (Colección estudios nº 119). Cuenca, Ecuador: Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha. [Google Scholar]

- Boeringer S. B. (1999). Associations of rape-supportive attitudes with fraternal and athletic participation. Violence Against Women, 5, 81-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondurant B. (2001). University women’s acknowledgment of rape: Individual, situational, and social factors. Violence Against Women, 7, 294-314. [Google Scholar]

- Boswell A. A., Spade J. Z. (1996). Fraternities and collegiate rape culture: Why are some fraternities more dangerous places for women? Gender & Society, 10, 133-147. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant S. A., Spencer G. A. (2003). University students’ attitudes about attributing blame in domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence, 18, 369-376. [Google Scholar]

- Burt M. R. (1980). Cultural myths and supports for rape. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 217-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantalupo N. C. (2012). “Decriminalizing” campus response to sexual assault. Journal of College and University Law, 38, 483-526. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano I., García M. J., Lago M. J., Ramírez de Arellano L. (1999). La violencia en las parejas universitarias [Violence in couples belonging to the university community]. Boletín Criminológico, 42, 1-4. [Google Scholar]

- Choate L. H. (2003). Sexual assault prevention programs for college men: An exploratory evaluation of the men against violence model. Journal of College Counseling, 6, 166-176. [Google Scholar]

- Coker A. L., Cook-Craig P. G., Williams C. M., Fisher B. S., Clear E. R., Garcia L. S., Hegge L. M. (2011). Evaluation of Green Dot: An active bystander intervention to reduce sexual violence on college campuses. Violence Against Women, 17, 777-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan G. (2000). Women’s hostility toward women and rape and sexual harassment myths. Violence Against Women, 6, 238-246. [Google Scholar]

- DeKeseredy W. S., Schwartz M. D., Alvi S. (2000). The role of profeminist men in dealing with woman abuse on the Canadian college campus. Violence Against Women, 6, 918-935. [Google Scholar]

- Dziech B., Weiner L. (1990). The lecherous professor: Sexual harassment on campus. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eyre L. (2000). The discursive framing of sexual harassment in a university community. Gender and Education, 12, 293-307. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B. S., Cullen F. T., Turner M. G. (1999). Extent and nature of the sexual victimization of college women: A national-level analysis (final report). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B. S., Daigle L. E., Cullen F. T. (2010). Unsafe in the ivory tower: The sexual victimization of college women. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald L. F., Shullman S. L., Bailey N., Richards M., Swecker J., Gold Y., et al. (1988). The incidence and dimensions of sexual harassment in academia and the workplace. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 32, 152-175. [Google Scholar]

- Flecha R., Puigvert L., Ríos O. (2013). The new masculinities and the overcoming of gender violence. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences, 2, 88-113. [Google Scholar]

- Fonow M. M., Richardson L., Wemmerus V. A. (1992). Feminist rape education: Does it work? Gender & Society, 6, 108-121. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes G. B., Jobe R. L., White K. B., Bloesch E., Adams-Curtis L. E. (2005). Perceptions of dating violence following a sexual and nonsexual betrayal of trust: Effects of gender, sexism, acceptance of rape myths and vengeance motivation. Sex Roles, 52, 165-173. [Google Scholar]

- García-Lastra M., Díaz-Díaz B. (2013). Equality of opportunities at Spanish universities? Learning from the experience. Multidisciplinary Journal of Gender Studies, 2, 255-283. [Google Scholar]

- Garlick R. (1994). Male and female responses to ambiguous instructor behaviors. Sex Roles, 30, 135-158. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez A., Munté A., Sordé T. (2014). Transforming schools through minority males’ participation: Overcoming cultural stereotypes and preventing violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 3, 2002-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grauerholz L., Gottfried H., Stohl C., Gabin N. (1999). There’s safety in numbers: Creating a campus advisers’ network to help complainants of sexual harassment and complaint receivers. Violence Against Women, 5, 950-977. [Google Scholar]

- Gross A. M., Winslett A., Roberts M., Gohm C. L. (2006). An examination of sexual violence against college women. Violence Against Women, 12, 288-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isonomia Foundation. (2010). El proceso de incorporación de la igualdad efectiva de mujeres y hombres en las universidades españolas. Análisis comparativo entre Universidades: planes de igualdad y unidades de igualdad universitarias [The process of incorporation of the effective equality of women and men in Spanish universities. Comparative analysis among universities: Equality Plans and Equality Committees in universities]. Castellón, Spain: Fundación Isonomía. [Google Scholar]

- Kalof L., Eby K. K., Matheson J. L., Kroska R. J. (2001). The influence of race and gender on student self-reports of sexual harassment by college professors. Gender & Society, 15, 282-302. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs C. P., Lindquist C. H., Warner T. D., Fisher B. S., Martin S. L. (2009). College women’s experiences with physically forced, alcohol or drug-enabled, and drug-facilitated sexual assault before and since entering college. Journal of American College Health, 57, 639-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Pomeroy E. C., Yoo S. K., Rheinboldt K. T. (2005). Attitudes toward rape: A comparison between Asian and Caucasian college students. Violence Against Women, 11, 177-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahlstedt D. L., Welsh L. A. (2005). Perceived causes of physical assault in heterosexual dating relationships. Violence Against Women, 11, 447-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks M. A., Nelson E. S. (1993). Sexual harassment on campus: Effects of professor gender on perception of sexually harassing behaviors. Sex Roles, 28, 207-217. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon S., Banyard V. L. (2012). When can I help? A conceptual framework for the prevention of sexual violence through bystander intervention. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 13, 3-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan M. M., Banyard V. L., Arnold J. S., Eckstein R. P., Stapleton J. G. (2011). Sisterhood May be powerful for reducing sexual and intimate partner violence: An evaluation of the bringing in the bystander in-person program with sorority members. Violence Against Women, 17, 703-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Union of Students. (2010). Hidden marks: A study of women students’ experiences of harassment, stalking, violence and sexual assault. London, England: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson M. E., Maney D. W., Blair K., Wamboldt P. M., Mahoney B. S., Yuan J. P. (1998). Trends in alcohol-related campus violence: Implications for prevention. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 43(3), 34-52. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver E., Soler M., Flecha R. (2009). Opening schools to all (women): Efforts to overcome gender violence in Spain. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 30, 207-218. [Google Scholar]

- Orchowski L. M., Gidycz C. A. (2012). To whom do college women confide following sexual assault? A prospective study of predictors of sexual assault disclosure and social reactions. Violence Against Women, 18, 264-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul L. A., Walsh K., McCauley J. L., Ruggiero K. J., Resnick H. S., Kilpatrick D. G. (2013). College women’s experiences with rape disclosure: A national study. Violence Against Women, 19, 486-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puigvert L. (2007-2010). Incidencia de la Ley Integral contra la Violencia de Género en la formación inicial del profesorado [Impact of the Organic Law on Integral Protection Measures Against Gender Violence in initial teacher’s training education]. Madrid: RTD Project, Ministry of Work and Social Affairs, Spanish Government. [Google Scholar]

- Puigvert L. (2008). Breaking the silence: The struggle against gender violence in universities. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 1(1), 1-6. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly M. E., Lott B. E., Caldwell D., DeLuca L. (1992). Tolerance for sexual harassment related to self-reported sexual victimization. Gender & Society, 6, 122-138. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly M. E., Lott B., Gallogly S. M. (1986). Sexual harassment of university students. Sex Roles, 15, 333-358. [Google Scholar]

- Renzetti C. M., Edleson J. L. (Eds.). (2008). Encyclopedia of interpersonal violence (Vols. 1-2). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D. T., Gibson-Beverly G., Schwartz J. P. (2004). Sorority and fraternity membership and religious behaviors: Relation to gender attitudes. Sex Roles, 50, 871-877. [Google Scholar]

- Roggeband C. (2012). Shifting policy responses to domestic violence in the Netherlands and Spain (1980-2009). Violence Against Women, 18, 784-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M. D., Leggett M. S. (1999). Bad dates or emotional trauma? The aftermath of campus sexual assault. Violence Against Women, 5, 251-271. [Google Scholar]

- Shepela S. T., Levesque L. L. (1998). Poisoned waters: Sexual harassment and the college climate. Sex Roles, 38, 589-611. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Zucosky H., Brasfield H., Febres J., Cornelius T. L., Sage C., Stuart G. L. (2012). Dating violence prevention programming: Directions for future interventions. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17, 289-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanish Government. (2004). Ley Orgánica 1/2004, De 28 de diciembre, de Medidas de Protección Integral contra la Violencia de Género [Organic Law on Integral Protection Measures Against Gender Violence]. Madrid, Spain: Boletín Oficial del Estado núm; 313. [Google Scholar]

- Spanish Government. (2007). La Ley Orgánica 3/2007, De 22 de marzo, para la Igualdad Efectiva de Mujeres y Hombres [Law for the Effective Equality between Women and Men]. Madrid, Spain: Boletín Oficial del Estado. [Google Scholar]

- Stombler M. (1994). “Buddies” or “Slutties”: The collective sexual reputation of fraternity little sisters. Gender & Society, 8, 297-323. [Google Scholar]

- Valls R. (2005-2008). Violencia de Género en las Universidades Españolas [Gender-based Violence in Spanish Universities]. Madrid: RTD Project, Ministry of Work and Social Affairs, Spanish Government. [Google Scholar]

- Vidu A., Schubert T., Muñoz B, Duque E. (2014). What students say about gender violence within universities: Rising voices from the communicative methodology of research. Qualitative Inquiry, 20, 883-888. [Google Scholar]

- Vladutiu C. J., Martin S. L., Macy R. J. (2011). College- or university-based sexual assault prevention programs: A review of program outcomes, characteristics, and recommendations. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 12, 67-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]