Short abstract

Examines the health care system in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, with an emphasis on primary care, and discusses what strategies can be pursued to move toward a more effective and higher-quality health care system.

Abstract

At the request of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), RAND researchers undertook a yearlong analysis of the health care system in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, with a focus on primary care. RAND staff reviewed available literature on the Kurdistan Region and information relevant to primary care; interviewed a wide range of policy leaders, health practitioners, patients, and government officials to gather information and understand their priorities; collected and studied all available data related to health resources, services, and conditions; and projected future supply and demand for health services in the Kurdistan Region; and laid out the health financing challenges and questions. In this volume, the authors describe the strengths of the health care system in the Kurdistan Region as well as the challenges it faces. The authors suggest that a primary care–oriented health care system could help the KRG address many of these challenges. The authors discuss how such a system might be implemented and financed, and they make recommendations for better utilizing resources to improve the quality, access, effectiveness, and efficiency of primary care.

This article describes the results of a yearlong effort conducted at the request of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) to analyze the current health care system in the Kurdistan Region—Iraq; to make recommendations for better utilizing resources to improve the quality, access, effectiveness, and efficiency of primary care; and to define the issues entailed in revising the existing health care financing system.

Approach

To conduct this work, RAND staff reviewed available literature on the Kurdistan Region as well as information relevant to primary care. We interviewed a wide range of policy leaders, health practitioners, patients, and government officials to gather information and understand their priorities, and we collected and studied all available data related to health resources, services, and conditions.

Using the available information, we described current service utilization, projected demand for services five and ten years into the future, and calculated the additional resources (beds, physicians, nurses, etc.) needed to meet future demand. We used this information and the articulated needs of the Kurdistan Region to develop an array of options for improving primary care organization and management, the health workforce, and information systems, and to address issues in health financing. We developed an extensive list of policy options and discussed them with key policy leaders in the Kurdistan Region and among the research team to rate them by importance and feasibility. We then used these criteria to identify a subset of policy changes as potentially the most important for implementation over the next two years.

Current Health System in the Kurdistan Region

The health system in the Kurdistan Region has many strengths:

Access to care is excellent. The majority of people live within 30 minutes of some type of primary health care center (PHC); in remote regions, hospital and emergency services are increasingly accessible.

The total number of health facilities is adequate. All governorates have public general, emergency, and pediatric hospitals, and most PHCs provide most of the basic primary care services.

Health care providers are knowledgeable and strongly committed to patient health. Some of the better physicians in Iraq have migrated to the Kurdistan Region.

The commitment of health system leaders is strong, and they have set appropriate strategic goals and priorities for improvement.

The primary health care system in the region also faces challenges:

The number of physician-staffed PHCs and the distribution of PHCs and medical staff are not optimal. The number of main PHCs (staffed by at least one physician) per capita falls short of international standards. Slightly fewer than 30 percent (249 of 847) of PHCs have at least one physician; the remaining 598 branch facilities do not. Services offered at each type of facility and reporting requirements are not standardized. Facilities are not systematically networked, and referrals are not well organized.

Primary care is of variable quality and availability. Quality is not systematically measured, and most personnel lack training in quality improvement methods. Many health authorities indicate that the quality of PHC services could be improved.

Physicians are poorly distributed and overworked, and nurses are underutilized and lack appropriate training. The number and distribution of medical staff are not optimal, especially in rural areas. Many general practitioners in PHCs are neither supervised nor mentored, and most physicians work only in the morning, devoting the rest of the day to private practice. Job descriptions and staff performance standards are lacking, and few health care managers are trained.

Health information systems are not systematically used to support policymaking, regulation, or system management. Data collection and analysis are not standardized, and computer technologies are not fully utilized. Data systems are inefficient, and data are not readily available; available data are not routinely used at all relevant levels. Patient record-keeping at ambulatory centers is virtually nonexistent.

Health care is generally financed by government budgets, and the financing system provides no incentives to promote efficiency. There is very little private insurance.

A primary care–oriented health care system could help the KRG address many of these challenges. An ideal model is an integrated health care system that offers services at the appropriate level of care; creates incentives for patients to seek urgent and other care in the community, when appropriate; and integrates health information across levels of care. Systems that integrate health care delivery produce consistently higher-quality care and better clinical outcomes, with associated lower costs.

Projecting Future Health Care Supply and Utilization for the Kurdistan Region

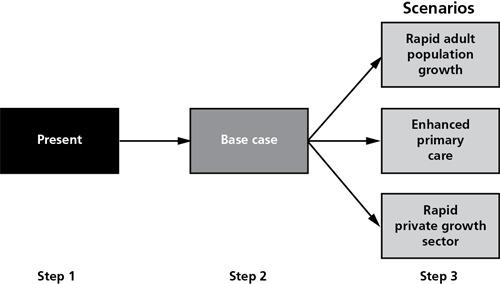

To estimate future resource needs, the RAND team projected future supply and demand for health services in the Kurdistan Region in a base case; this model assumed that the current health services provided and current patterns of health service utilization remained unchanged through 2020. We then changed the assumptions in the model to compare the gap between supply and needs under different scenarios (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of Modeling Plan

Estimating Demand for Health Care: Base Case

We first projected health care supply and utilization for 2015 and 2020, assuming moderate population growth consistent with the levels of growth the Kurdistan Region has experienced recently (3 percent annual growth between 2010 and 2020) and unchanged patterns of health service delivery and utilization. Table 1 shows the additional resource needs under these conditions.

Table 1.

Projected Workforce and Hospital Bed Needs—Base Case

| Health Care Resources | 2015 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital beds | +1,343 | +2,574 |

| Physicians | +1,070 | +2,097 |

| Nurses | +1,681 | +3,325 |

| Dentists | +126 | +246 |

| Pharmacists | +82 | +151 |

Estimating Demand for Health Care: Three Future Scenarios

We then estimated how the additional resources needed would change under different assumptions (see Table 2), focusing on three indicators of future health service utilization for each governorate:

Table 2.

Summary of Projected Changes in Resource Requirements in 2020 for Each Scenario, Compared with the Base Case (% difference)

| Scenario | Hospitalizations | ED Visits | Outpatient Visits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid population growth | 28.2% | 74.2% | 7.9% |

| Improved primary care (lower-bound estimate) | −1% | −20% | 20% |

| Growth in private sector health care (lower-bound estimate) | 2.0% | 0% | 5.0% |

| Growth in private sector health care (upper-bound estimate) | 10.0% | 0% | 20.0% |

Total hospital admissions

Total emergency department (ED) visits

Total number of outpatient visits.

Scenario 1 assumes rapid population growth due to expansion of the oil economy, with an approximate 2.4-percent yearly influx of foreign workers, primarily young male adults. The increase in net migration will result in an average annual population growth rate of 4.8 percent between 2010 and 2020 and a total projected population of about 8.75 million by 2020. These foreign workers will have higher rates of hospitalization and ED use, and lower rates of outpatient care utilization. Under this scenario, hospitalizations could increase by as much as 28 percent over the base case by 2020, ED use by as much as 74 percent, and outpatient visits by as much as 8 percent.

Scenario 2 assumes enhanced primary care, meaning fewer hospitalizations for care that could be provided in ambulatory facilities, increased outpatient utilization, and decreased ED utilization. These assumptions will result in a 20-percent reduction in hospitalizations for chronic disease, a 20-percent increase in outpatient visits, and a 20-percent decrease in ED utilization.

Scenario 3 assumes expansion of the private health care sector. This assumption will result in broad increases in utilization (2- to 10-percent increase in inpatient utilization, a 5- to 20-percent increase in outpatient utilization, and no change in use of emergency care).

We draw the following conclusions from our modeling effort:

Population is the main driver of future health care use.

Significant investment in health care (physicians, hospitals, and PHCs) will be needed to meet the projected demand for care.

Better primary care could reduce hospitalizations and emergency room use.

The growth in private sector health care will increase systemwide utilization in most areas.

Health Care Financing System

The KRG's Minister of Planning asked RAND to review the basic tenets of health care financing and to develop a road map to help guide KRG policy development in this area. We (1) provided an overview of health care financing and its basic tenets, (2) examined how other countries have dealt with financing issues, (3) developed a general profile of the Kurdistan Region's present health care financing system, and (4) defined the questions the KRG will need to address as it considers its future financing system.

Health care financing is the process of mobilizing, accumulating, and allocating money to cover the health needs of the population, individually and collectively. The purpose of health financing is to make funding available and to give providers the right incentives so that everyone has access to effective public and personal health.

No two countries finance health care exactly the same way, because each country has its own objectives, cultural context, and health status. But every health financing system must answer the following questions:

Who is eligible for health care coverage?

Which services are covered?

What is the source of funds to pay for services?

How are funds pooled?

How is payment made for services provided?

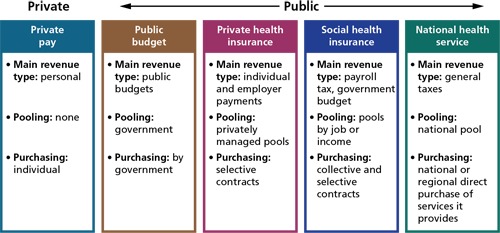

Most financing systems fall into one of the five general types of health financing systems shown in Figure 2. The type of system a country has depends on a range of factors, including data systems, ability to collect taxes, the public workforce, number of physicians, education of the population, and the sophistication of the banking and insurance systems. Almost all countries have mixed systems.

Figure 2.

Common Health Care Financing Systems

A country's health care financing system is a critically important component of its health care system that enables all other parts. The financing system enables equitable collection of sufficient resources in order to offer efficient, quality care to all segments of society. The financing system defines the compensation that providers will receive and embodies incentives that help determine efficiency and quality of care. The system also reflects a country's basic cultural and economic values.

Kurdistan's current health care financing system is primarily a public budget system. All Iraqis are covered under the system, and a wide range of primary, hospital, and other medical care is offered in the public facilities, where most health care is provided. Some services are provided by private hospitals and physicians in private practice.

Most services are paid for out of public budgets (KRG, governorates, or Baghdad); private physician and hospital services are paid for by individuals. In theory, the government regulates both the public and private health care sectors. Private insurance is almost nonexistent. Co-pays are very low. Costs are rising quickly, as are payments for care abroad. The system provides few incentives for efficiency, quality, or cost control.

The Kurdistan Region currently lacks the sophisticated data, information technology (IT) systems, and managerial skills required to successfully operate more management-intensive systems such as social insurance or national health plans. These requirements must be in place before the KRG can successfully embark on reform. However, the Kurdistan Region is rapidly developing. In the near future, it can likely take the next step in establishing health financing systems that are not primarily budget driven. Careful planning and wise choices can help the Kurdistan Region achieve the health outcomes of much richer countries at a greatly reduced cost.

To examine other finance system options, the KRG will need to address multiple dimensions of the five key questions described above. These dimensions are given below.

Who is eligible for health care coverage?

Will non-Kurdistan, non-Iraqi citizens receive the same health care benefits that Kurdistan citizens receive, and if so, will they pay the same amount?

Will/can the KRG and Iraq have different financing plans with different benefits? If so, how will benefits be coordinated?

How will the KRG administer and verify eligibility (for example, issue an insurance identification card)?

Which services are covered?

Which services will and will not be covered?

What process will the KRG use to decide coverage?

How will the list of covered services be updated for new technologies?

How will treatment for services not available in the Kurdistan Region be financed?

What is the source of funds to pay for services?

What share of national income will be allocated to health care?

Who will bear the burden of providing resources: the government (the KRG or governorate), individuals, and/or companies?

What will be the size of co-payments and deductibles, and will they vary by type of service?

How will care for the poor be financed?

How much will non-Kurdistan residents pay for treatment?

How are funds pooled?

Will the KRG continue to utilize the national budget to pool resources or will it move toward some form of insurance?

If the KRG pursues an insurance system, will it be public or private, voluntary or compulsory?

How will the KRG and Baghdad rationalize and coordinate systems?

How is payment made?

What mechanism(s) will be set up to process and pay for services and staff?

Will there be incentives in the system to encourage efficiency and productivity?

What will the payment rates for services be?

Will a prospective payment system be used to encourage efficiency?

Should payment be linked to performance or level of effort for providers, hospitals, PHCs, and so forth?

As part of the process of assessing which health financing system might be best for the Kurdistan Region, it is worth noting that spending a great deal on health care does not guarantee good health outcomes. For instance, the United States spends more than $7,000 per capita on health care—more than any other country. However, in Korea, which spends about $1,500 per capita on health care, life expectancy is higher than in the United States; higher life expectancy and lower per capita spending is also the case for Cuba, Japan, Spain, France, Switzerland, Canada, Norway, Denmark, and the United Kingdom. Many factors besides expenditures on health care contribute to life expectancy, but the way in which countries organize and spend their limited health care dollars can have a profound influence.

Deciding on and establishing a health financing system is a complex and demanding undertaking. To make good policy decisions, the KRG should review all policy options and choices, with special attention to the following key questions:

What data are required to manage any system?

What actions can be taken now to improve efficiency and control costs?

What incentives should be embedded in the system to ensure quality health care for all residents of the Kurdistan Region?

It will also be necessary to develop a strategic health care financing plan and define a research agenda to fulfill it. The financing system will be key to the effective functioning of the health care system in the Kurdistan Region as well as to the region's development and the health of its people.

Improving Primary Care

Primary care is key to the success of a modern health care system. Primary care anchors the organization of health services by providing an ongoing patient-clinician connection for delivery of most care and a pathway to and from other sources of care. Since improving primary care services is essential to ensuring access to care for all people living in the Kurdistan Region, it is not surprising that the Minister of Health and other KRG authorities have highlighted it as a high priority.

To address this priority, we examined the organization and management of primary care, and associated needs related to the health workforce and health information systems. Improvements in these areas underpin the entire health care system in the Kurdistan Region, now and into the future. Improvements can build on Kurdistan's tradition of medical excellence while expanding, upgrading, and modernizing health services.

Based on an analysis of the current system, discussions with health care leaders and managers throughout the region, and the guiding principles of primary care in the Twenty-First Century endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM), the RAND team made recommendations for improving Kurdistan's primary care system in three areas: (1) organization and management of primary care facilities and services, (2) the health care workforce, and (3) health information systems.

Organization and Management of Primary Care Facilities and Services

The present organization and management of the KRG primary health care system has important strengths on which to build. At the same time, it also presents challenges that must be addressed in order to improve the efficiency, continuity, and quality of primary care service delivery. Below we discuss three major initiatives designed to improve the organization and management of primary care facilities and services:

Distribute facilities and services efficiently

Develop and implement a system for referrals and continuity of care

Develop and implement a program for continuous quality improvement (CQI).

Distribute Facilities and Services Efficiently. The types, sizes, and locations of hospitals are relatively standardized across the Kurdistan Region. However, primary health care centers (PHCs) are much less standardized, and the number of main PHCs (those staffed by a physician) on a per capita basis falls short of international and Iraqi standards. Iraqi law defines different types of health centers (labeled as Types A–G) and establishes criteria for the population covered, physical infrastructure, and staffing at each type of facility; however, it is clear that these criteria have not been applied in a systematic and consistent fashion across the region.

Functionally, the primary care system in the Kurdistan Region is based on two levels of PHCs:

PHC Main Center (Types A, B, C)—In general a main PHC serves a population of 5,000–10,000 and is staffed by at least one physician. A main PHC has the capacity to deliver all primary care services. Type B centers also serve as medical and paramedical training centers; Type C centers provide uncomplicated obstetric deliveries and simple medical and surgical emergency care.

PHC Subcenter/Branch (Type D)—In general a branch PHC serves a population of up to 5,000 and is staffed by a male nurse, a female nurse, and a paramedical assistant. It provides simple maternal and child health services, immunizations, and simple curative services.

Health authorities have suggested that PHCs are not necessarily distributed appropriately, nor are they systematically standardized or monitored by such criteria as type, size of population served, staffing level, and services offered. Many of the basic or “traditional” primary care services are already provided in the Kurdistan Region, but not consistently. Experts have also persuasively argued that chronic disease management now be included in the package of primary care services, since nearly three-fourths of avoidable mortality—including a significant proportion of deaths in the Kurdistan Region—can be attributed to behavioral and environmental factors, such as diet, exercise, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption. Experience shows that each of these can be significantly reduced through public education and other prevention-oriented interventions.

A key aim in the Kurdistan Region should be to make primary care services more comprehensive and more uniformly and universally accessible at appropriate levels of care. The absence of functional KRG standards for catchment areas, staffing, and services hampers efficiency and systematic improvement. The goals of universal access and high-quality care cannot be achieved without systematic application of such standards. Making the scope of services more uniform at each level of care is also a prerequisite to improving service quality, efficiency, and staff productivity. Therefore, we recommend that immediate attention be given to (a) aligning services with appropriate levels of care, (b) ensuring that facilities are properly equipped and staffed and can provide all appropriate services, and (c) ensuring the quality of those services.

The distribution of primary care facilities and services is intended to achieve primary care–oriented health care delivery that is accessible, patient-centered, integrated, efficient and meets the Twenty-First-Century needs of the Kurdistan population. With these objectives in mind, we recommend six strategies to improve the efficient distribution of facilities and services while maintaining sufficient flexibility to reflect different local conditions:

Define the appropriate scope of services to be provided at public sector clinics

Organize the system of existing and new PHCs based on a core three-tiered networked system and specified access standards

Develop a plan to provide services based on standards appropriate for each type of facility

Extend the reach and quality of health services through telemedicine

Expand health education activities in clinics and schools

Develop and implement health education campaigns for the public to promote safe and healthy behaviors of greatest relevance to the region.

All of these recommendations are important. However, the first two appear to be the most important and feasible for the near term.

Develop and Implement a System for Referrals and Continuity of Care. As a key report from WHO clarifies, patients should have a regular point of entry into the health system and an ongoing relationship with their primary care team (WHO, 2008). The resulting continuity of care means that patient care is not simply episodic—neither patients nor providers should have to start from the beginning with every primary care or specialist visit. Ideally, there would be no gaps in care due to lost information or failed communication between providers. Effective care depends on continuity, not only in general primary care, but also in chronic disease management, reproductive health, mental health, and healthy child development. Continuity of care also requires that the system be as easy to use as possible for patients.

Currently, the Kurdistan Region has no system in place to give patients a consistent point of contact with the health care system—for example, a designated primary care provider or team. Likewise, there is no established method for communication between a referring provider and a consultant specialist. These two components of continuity of care are critical contributors to more cost-effective care and better health outcomes.

A system for referrals and continuity of care aims to ensure that patients receive services at the most appropriate time and in the most appropriate setting and that care is well coordinated across care levels and providers. Patients referred to specialists and hospitals should be able to return to their home clinic and primary care provider for follow-up or ongoing management. Ideally, this means that a patient should see the same primary care provider, or at least the same team of providers, at each visit, and that referrals out to and back from specialty care entail smooth transitions in both directions.

Such a system is built on a foundation of quality services at each level of care. Also, at a minimum, all providers should have access to the patient's health care record so that they are aware of important test or examination results and do not waste resources duplicating efforts. Electronic health records greatly facilitate effective systems for referrals and continuity of care, but they are not the only way to achieve this goal. In this report we offer four recommendations for improving referrals and continuity of care:

Develop and implement a patient referral system

Explore the feasibility of designating population catchment areas and a “home clinic” and “primary care provider” for all population members

Take initial steps in a transition to electronic health records at all levels across the region to facilitate referrals and continuity of care

Promote local awareness of available services, appropriate use, and referrals within and beyond the local catchment area.

All of these recommendations are important, but they are challenging to address collectively in the near term. The first recommendation appears to be most important and at least moderately feasible.

Develop and Implement a Program for Continuous Quality Improvement. IOM (2005) has identified six desired attributes of quality health care, and WHO (2008) has persuasively argued for a seventh:

Safety: Avoiding injuries to patients from the care that is intended to help them

Effectiveness: Providing services based on scientific knowledge (evidence-based) to all who could benefit, and refraining from providing services to those not likely to benefit (minimizing underuse and overuse, respectively)

Patient-centeredness: Providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values are considered in making clinical decisions

Timeliness: Avoiding waits and sometimes harmful delays for both those who receive care and those who give care

Efficiency: Avoiding waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy

Equity: Providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic status

Access: Health care is available to everyone in the region. Facilities are appropriately located and provide an appropriate scope of services; residents are aware of available services and are physically and financially able to access them.

So far, there is no consistent program to assess the current quality of health care delivery in the Kurdistan Region, draw lessons from any issues found, or institute appropriate changes or incentives within the system to encourage quality. These activities are the heart of continuous quality improvement (CQI), an essential component of effective care.

The goal of CQI is to help health systems and professionals consistently improve the quality of health care delivery and outcomes through access to effective knowledge and tools. An essential requirement for CQI is establishing clinical practice standards that are uniform and based on best evidence. In this report we offer six specific interventions related to CQI:

Develop and implement evidence-based clinical management protocols for common conditions seen at ambulatory (and hospital) facilities

Define and expand the safe scope of practice for nurses in ambulatory settings

Consider standardized patient encounter forms (e.g., checklists) to facilitate use of clinical management protocols at PHC facilities at all levels

Identify and test efficiency measures to enhance patient flow

Develop and implement carefully focused surveys of client and staff satisfaction on a routine basis at PHC facilities

Begin to explore the feasibility of a regional and, ultimately, international accreditation process for ambulatory and hospital inpatient services.

Continuous quality improvement is a process needed at all levels of a health care system, but addressing the full range of interventions to establish such a system in the Kurdistan Region will take time. In the near term, the first two interventions listed above appear to be the most important and are at least moderately feasible. Thus, they might be the appropriate priorities in the near term.

The Health Workforce

Many studies have demonstrated that the size and qualifications of a country's health workforce are associated with health outcomes. Preparing the workforce—including doctors, nurses, midlevel health workers, and others—requires both careful planning and strategic investments in education that are designed to address the country's key health system priorities. Once trained, the workforce needs to be properly managed (i.e., clinical skills monitored, maintained, and updated). Policies and incentives are needed to achieve these objectives.

Iraq has a long tradition of excellence in medical services and training. Some of Iraq's best physicians have recently migrated to the Kurdistan Region. Although the KRG health system experienced significant erosion during Saddam Hussein's regime, since 1991 the situation has begun to stabilize. The current health care workforce has notable strengths, but important areas for improvement remain in terms of size and qualifications. For example, the Kurdistan Region has fewer physicians per capita than many other countries in the region. Physician shortages involve training/competencies as well as numbers, distribution (shortages are especially pronounced in rural areas), and hours worked.

In the Kurdistan Region, public sector ambulatory care relies almost exclusively on the obligatory one-year service of junior general-practice physicians after they have completed one or two years of post-graduate clinical (residency) training. This year of obligatory clinic service is not itself treated as a year of formal clinical training. During this year, these physicians receive no mentorship, supervision, or other professional development support, and they have limited access to professional resources, such as the Internet or professional journals. Virtually all of them provide clinic services in the morning and see private patients in the afternoon. All physicians who complete their clinical training have guaranteed government jobs (and pensions), but they receive relatively meager government salaries for public sector work and derive much more substantial income from seeing private patients.

According to KRG health authorities and our own observations, problems with the nursing profession are especially critical. The Kurdistan Region has more nurses per capita than some countries in the region but fewer than other countries. However, the Minister of Health has indicated that the number of nurses in Kurdistan may not be quite as critical a problem as the distribution, qualifications, and competencies of nurses across all levels. The Minister of Health and most other health authorities we consulted are particularly concerned about an absence of defined nursing competencies, an absence of defined responsibilities and duties, and the resulting inefficient use of nurses in clinical care.

Below we discuss two strategies for improving the health workforce in Kurdistan:

Enhance professional qualifications through education and training

Improve the distribution and performance of the health workforce through specific human resource management interventions.

Enhance Professional Qualifications Through Education and Training. A trained workforce forms the core of every health care system. Both the number and the quality of health workers demonstrably affect all health outcomes, and the decisions the health workers make determine whether resources are used efficiently and effectively. Research shows that a workforce makes best use of available resources if its members are properly trained and motivated. IOM (2005) recommends education that includes practical experience that allows clinicians to master five core competencies: (1) patient-centered care, (2) ability to work in interdisciplinary teams, (3) utilization of evidence-based practice, (4) application of quality improvement, and (5) utilization of informatics.

In this article, we offer eleven specific interventions for improving professional education and training:

Establish an executive professional committee to develop and oversee new professional education, training, licensing and recertification standards, recruitment of students across the medical professions, and management of the supply of medical personnel to meet forecasted demand

Preferentially recruit medical and nursing students from rural areas as a means to attract professionals to more permanent rural service

Include primary care in the curricula of medical and nursing schools

Improve the experience of general practice physicians during their year of obligatory medical service in primary care centers by providing preferential incentives for rural service and professional development opportunities

Enhance the profile of family medicine as a foundation for modern medical care and medical education

Include primary care in the clinical rotations of medical and nursing schools

Enhance training in practical clinical skills during medical and nursing school training, internship, rural rotation year, and all post-graduate training

Complete redesign of and implement new nursing curriculum and training at each of the KRG's three levels of nurse training (university, college, institute)

Develop and implement a mandatory continuing education system for medical, nursing, dental, and pharmacy professionals

Develop and implement a system for licensing and revalidation for medical professionals

Enhance training and create a strong career track for preventive medicine specialists.

All of these interventions are all potentially valuable ways to improve professional qualifications. However, the first four might be the most appropriate near-term priorities because of their importance and feasibility.

Improve the Distribution and Performance of the Health Workforce Through Specific Human Resource Management Interventions. Recruiting and retaining health care workers, especially in remote/rural areas, is a problem not unique to Kurdistan. It is a worldwide phenomenon that has been a focus of considerable research effort. WHO has documented several factors that influence the choices of doctors, nurses, and midwives to work in rural areas. Some factors attract workers (for example, better employment opportunities or career prospects, better income and allowances, better living and working conditions, better supervision, and a more stimulating environment for worker and family). Other factors repel health care workers from rural assignments (for example, poor job security, poor socioeconomic environment, poor working and living conditions, poor access to education for the worker's children, inadequate availability of employment for the worker's spouse, and work overload).

In this report we offer six specific interventions to help improve health workforce management:

Develop, implement, and monitor required qualifications and job descriptions for professional staff at all relevant levels

Develop a plan to distribute staff based on standards defined in law for each type of facility

Define and implement systematic and supportive supervision for physicians, nurses, and other health professionals serving in PHCs, especially in rural/remote areas

Institute appropriate incentives to attract medical and nursing staff to serve (and remain) in rural/remote areas

Increase the use of online human resource management forms, including applications for study, training, placement, licensure, continuing education, and related documentation

Develop and implement strategies to reduce fraudulent private medical practice by unauthorized personnel (e.g., medical assistants advertising themselves as and providing services of physicians).

All of these interventions could help improve management of the health workforce. However, the first is very important and appears feasible in the near term.

Health Information Systems

Modern health information systems are essential to improving quality and efficiency. A health care system depends on data to inform wise investments in policies and programs and to monitor their implementation. Ideally, data are processed into information of sufficient scope, detail, quality, and timeliness to confidently manage health care services at all levels. Management information systems (MISs) make it possible to monitor health resources, services, and clinic utilization. Surveillance and response systems support the monitoring of mortality, morbidity, and health risk factors. Implementing such systems requires trained personnel and standardized data collection, processing, analysis, and presentation. Patient record-keeping is a key element in the management of primary care facilities and underpins efficient referrals and continuity of care.

It is clear that KRG policymakers wish to have such data. However, a “culture of data for action”—where data collection, processing, analysis, presentation, and use are routine and relatively easy—remains elusive. Below we discuss two broad strategies, corresponding to two broad types of health information systems:

Develop and implement health management information systems

Enhance surveillance and response systems.

Both of these types of systems serve managers at the regional, governorate, and district levels and are critical; improvements are highly feasible in the near term because the important foundations are already in place.

A third type of data system—patient clinical record-keeping—primarily serves clinical providers and patients and is also critically important to primary care. However, the foundations are not yet in place for such a system. Efforts to lay these foundations should be a near-term priority.

Develop and Implement Health Management Information Systems. Health MISs include data on health resources (e.g., facilities, staffing, equipment, supplies, and medications) and services provided, as well as health service utilization (number of clients served by each service provided). MISs support management of health resources and can help ensure service coverage, performance, and efficiency. For example, these systems can be used to help managers and policymakers track the distribution of health facilities/services to ensure adequate coverage; the services delivered at specified health facilities; the number and qualifications of health workers providing these services; the equipment and supplies at health facilities providing preventive, diagnostic, and treatment services; the utilization of health services; the percentage of the target population covered by each type of service; the efficient use of health facility staff; the proportion of the intended population that receives preventive services; and patient referrals and continuity of care across different levels and providers of health services.

In this article we offer two main recommendations for developing and implementing health MISs, each with numerous subcomponents:

Monitor clinic resources and services

Monitor clinic utilization.

The first recommendation appears to be most important and feasible to pursue in the near term. Monitoring of clinic utilization also seems very important and only slightly more difficult. Both would significantly enhance management and, ultimately, the efficiency and effectiveness of primary health care services.

Enhance Surveillance and Response Systems. Public health surveillance is the ongoing, systematic collection and dissemination of health-related data to be used for public health action and ongoing management. These data include mortality, morbidity, and risk factors for communicable diseases, noncommunicable diseases, and injuries. Desirable attributes of any surveillance system include broad and representative coverage, high-quality data, and timeliness. Such systems enable effective monitoring of trends in health outcomes and risk factors, timely detection of unusual health events, and appropriate action to respond to anomalous events or trends. Taking responsible action based on surveillance requires information collection designed to be actionable, adequate workforce size and analytic capabilities (particularly in the areas of applied epidemiology and statistics), and established response mechanisms and procedures (especially for epidemiological investigation of outbreaks, implementation of appropriate control measures, and/or design of further research).

This article offers eleven strategies to improve KRG surveillance and response systems:

Standardize the diseases and conditions to be included in routine surveillance

Standardize data collection forms (for indicator-based surveillance)

Hire and/or train personnel who will be responsible for specific surveillance functions

Conduct a systematic assessment of current surveillance systems across the Kurdistan Region, from the local level to the regional level

Standardize the sources of surveillance information

Standardize reporting processes, from the local level to the regional level

Streamline data processing at the governorate and regional levels

Develop and disseminate standardized analyses for surveillance information at all appropriate levels (district, governorate, region)

Develop and implement a system for immediate alerts (event-based surveillance)

Develop and implement standardized protocols for responding to events warranting timely investigation

Monitor health risk factors.

These strategies largely represent a logical progression for improving surveillance and response and are all valuable for achieving that overall goal. However, near-term priorities might focus on the first three strategies, which we judged to be the most important and the most feasible.

Looking to the Future

The KRG has made significant progress in improving the region's health care services and the health of its people. However, more can be done, especially with respect to improving the health care system's quality, efficiency, organization, management, workforce, and data systems. Such initiatives will be increasingly important as Kurdistan continues its trajectory of modernization and integrates more closely with the rest of the world.

Footnotes

The research described in this article was sponsored by the Kurdistan Regional Government and was conducted in RAND Health, a division of the RAND Corporation.

References

- Institute of Medicine, Quality Through Collaboration—The Future of Rural Health, Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- IOM—See Institute of Medicine. [DOI] [PubMed]

- WHO—See World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization, The World Health Report 2008: Primary Health Care: Now More Than Ever, Geneva, 2008.