Short abstract

This article distills a longer report, Hidden Heroes: America's Military Caregivers. It describes the magnitude of military caregiving in the United States, identifies gaps in support services, and offers recommendations.

Abstract

While much has been written about the role of caregiving for the elderly and chronically ill and for children with special needs, little is known about “military caregivers”—the population of those who care for wounded, ill, and injured military personnel and veterans. These caregivers play an essential role in caring for injured or wounded service members and veterans. This enables those for whom they are caring to live better quality lives, and can result in faster and improved rehabilitation and recovery. Yet playing this role can impose a substantial physical, emotional, and financial toll on caregivers. This article distills a longer report, Hidden Heroes: America's Military Caregivers, which describes the results of a study designed to describe the magnitude of military caregiving in the United States today, as well as to identify gaps in the array of programs, policies, and initiatives designed to support military caregivers. Improving military caregivers' well-being and ensuring their continued ability to provide care will require multifaceted approaches to reducing the current burdens caregiving may impose, and bolstering their ability to serve as caregivers more effectively. Given the systematic differences among military caregiver groups, it is also important that tailored approaches meet the unique needs and characteristics of post-9/11 caregivers.

Many wounded, injured, or disabled veterans rely for their day to day care on informal caregivers: family members, friends, or acquaintances who devote substantial amounts of time and effort to caring for them. These informal caregivers, who we term military caregivers, play a vital role in facilitating the recovery, rehabilitation, and reintegration of wounded, ill, and injured veterans. The assistance provided by caregivers saves the United States millions of dollars each year in health care costs and allows millions of veterans to live at home rather than in institutions.

Yet the toll of providing this care can be high. A preliminary phase of our research commissioned by Caring for Military Families: the Elizabeth Dole Foundation (Military Caregivers: Cornerstones of Support for Our Nation's Wounded, Ill, and Injured Veterans, Tanielian et al., 2013) found that time spent caregiving can lead to the loss of income, jobs, or health care and can exact a substantial physical and emotional toll. To the extent that caregivers' well-being is compromised, they may become unable to fulfill their caregiving role, leaving the responsibilities to be borne by other parts of society. Most of this prior research focused on caregivers in general, with little evidence about the impact of caregiving on military caregivers specifically. In recognition of their growing number, particularly in the wake of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, it has become paramount to understand the support needs of military caregivers and the extent to which available resources align with those needs.

This article presents results from the second phase of our analysis, which represents the most comprehensive examination to date of military caregivers. It examines the characteristics of caregivers, the burden of care that they shoulder, the array of services available to support them, and the gaps in those services.

What We Did: Study Purpose and Approach

To inform an understanding of military caregivers and efforts to better support them, the goals of our analysis are threefold:

Describe the magnitude of military caregiving in the United States, including how caregiving affects individuals, their families, and society. We describe the number and characteristics of military caregivers and their role in ensuring the well-being of their care recipient. We employed a social-ecological framework to assess the effects of caregiving on military caregivers, their families, and society more broadly. We also examine how these effects differ across cohorts of veterans.

Describe current policies, programs, and other initiatives designed to support military caregivers, and identify how these efforts align with the needs of military caregivers. We review the existing policies and programs and assess how these initiatives address specific caregiver needs.

Identify specific recommendations for filling gaps and ensuring the well-being of military caregivers.

To address these goals, the study team performed two tasks: a nationally representative survey of military caregivers and an environmental scan of programs and other support resources relevant to the needs of military caregivers.

Caregiver Survey

We conducted the largest and most comprehensive probability-based survey to date of military caregivers. One respondent from each of the 41,163 households that participate in the KnowledgePanel (an online panel of households designed to represent the U.S. general population of non-institutionalized adults) was invited to complete a screener to determine eligibility for the survey across one of four groups: military care recipients, military caregivers, civilian caregivers, and non-caregivers. Of these 41,163 households, 28,164 (68 percent) completed the screener. We also drew upon a supplementary sample of post-9/11 family caregivers from the Wounded Warrior Project (WWP) to ensure an adequate number of these military caregivers in the final sample, which was blended into the KnowledgePanel sample using a statistical algorithm to create weights to account for systematic and observed differences between the groups. From these samples, we interviewed 1,129 military caregivers (including 414 post-9/11 caregivers).

In addition, we interviewed samples from two other groups for comparison: 1,828 civilian caregivers and 1,163 non-caregivers. These comparison samples provided information about the extent to which outcomes among military caregivers are unique and shed light on whether the policies and programs that exist for caregivers more broadly can be similarly marketed and offered to military caregivers, or if they need to be adapted to cater to this group.

Environmental Scan

Prior environmental scans have offered some insight into caregiver services in specific areas, sectors, or populations—for example, respite services available at a state level—but no studies have examined the full spectrum of services available for military caregivers within the United States on a national level. We used a multipronged search strategy that included web searches, sorting through the National Resource Directory, consultations with nonprofit staff and subject matter experts, attendance at relevant meetings and events, and snowball sampling among service organizations (i.e., asking organizations about other organizations they knew of that offer programs and services to military caregivers). We also conducted interviews with the organizations that offered services involving direct or intensive interaction with caregivers (see the “Common Caregiving Services” section for a listing of these types of services). A total of 120 distinct organizational entities were identified. Using a structured abstraction tool, we gathered information to document the publicly available information about programs that support caregivers. We added to this information using a semistructured interview tool to gain additional insights and information from 81 of the organizations. We asked questions to understand the history, origin, funding source, and objective of the programs. We also asked detailed questions about eligibility criteria, types of services offered, mode/mechanism of delivery, and whether any data had been gathered to assess the impact of the program on caregivers.

Common Caregiving Services

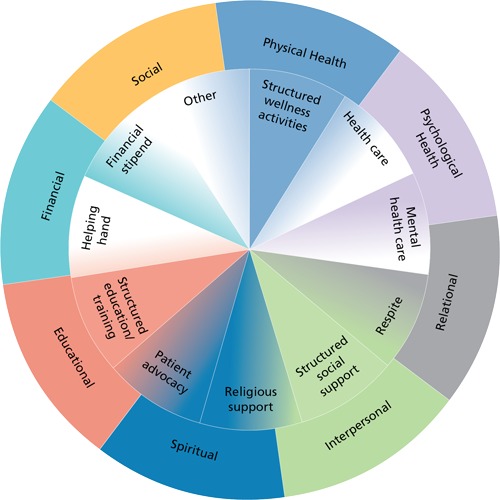

These are some of the most common services offered by programs that assist military caregivers (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Caregiving Needs and Services

The outer ring represents the multiple dimensions of caregiver needs; the inner wheel represents the different types of services that programs offer. This is portrayed as a wheel because different types of programs might address different dimensions of need.

Respite care: Care provided to the service member or veteran by someone other than the caregiver in order to give the caregiver a short-term, temporary break

Patient advocate or case manager: An individual who acts as a liaison between the service member or veteran and his or her care providers, or who coordinates care for the service member or veteran

A helping hand: Direct support, such as loans, donations, legal guidance, housing support, or transportation assistance

Financial stipend: Compensation for a caregiver's time devoted to caregiving activities and/or for loss of wages due to one's caregiving commitment

Structured social support: Online or in-person support groups for caregivers or military family members (which may incidentally include caregivers) that are likely to assist with caregiving-specific stresses or challenges

Religious support: Religious- or spiritual-based guidance or counseling

Structured wellness activities: Organized activities, such as fitness classes or stress relief lessons, that focus on improving mental or physical well-being

Structured education or training: In-person or online classes, modules, webinars, manuals, or workbooks that involve a formalized curriculum (rather than ad hoc information) related to caregiving activities.

Nonstandard clinical care:

Health care: Health care that is (1) offered outside of routine or traditional channel such as common government or private-sector payment and delivery systems, or (2) offered specially to caregivers

Mental health care: Mental health care that is (1) offered outside of routine or traditional channels such as common government or private-sector payment and delivery systems, or (2) offered specially to caregivers.

What We Found: The Study Results

Post–9/11 Military Caregivers Differ from Other Caregivers

We estimate that there are 5.5 million military caregivers in the United States. Of these, 19.6 percent (1.1 million) are caring for someone who served in the military after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. In comparing military caregivers with their civilian counterparts, we found that military caregivers helping veterans from earlier eras tend to resemble civilian caregivers in many ways; by contrast, post-9/11 military caregivers differ systematically from the other two groups. In sum, post-9/11 caregivers are more likely to be

younger (more than 40 percent are between ages 18 and 30)

caring for a younger individual with a mental health or substance use condition

nonwhite

a veteran of military service

employed

not connected to a support network (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Key Differences in Caregiver Populations

| Characteristics | Post-9/11 Military | Pre-9/11 Military | Civilian |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most common caregiver relationship to person being cared for | Spouse (33%) | Child (37%) | Child: (36%) |

| Percentage of caregivers age 30 or younger | 37 | 11 | 16 |

| Percentage of caregivers between ages 31–55 | 49 | 43 | 44 |

| Percentage of caregivers with nonwhite racial/ethnic background | 43 | 25 | 36 |

| Percentage of caregivers who are employed | 76 | 55 | 60 |

| Percentage of caregivers who have support network | 47 | 71 | 69 |

| Percentage of caregivers who have health insurance | 68 | 82 | 77 |

| Percentage of caregivers who have regular source of health care | 72 | 88 | 86 |

| Care Recipients | |||

| Percentage of care recipients with mental health or substance use disorder | 64 | 36 | 33 |

| Percentage of care recipients with VA disability rating | 58 | 30 | N/A |

Post-9/11 Caregivers Use a Different Mix of Services

We found that 53 percent of post-9/11 military caregivers have no caregiving network—an individual or group that regularly provides help with caregiving—to support them. Perhaps because they lack such a network, post-9/11 caregivers are more likely than other caregivers to use mental health resources and to use such resources more frequently. Similarly, they use other types of support services more frequently, such as helping hand services, structured social support, and structured education and training on caregiving (see the “Common Caregiving Services” section for a description of common support services).

Military Caregivers Perform a Variety of Caregiving Tasks

Post-9/11 military caregivers also differ from other caregivers in that they typically assist with fewer basic functional tasks, but more often assist care recipients in coping with stressful situations or other emotional and behavioral challenges. Tasks that all caregivers perform are sometimes grouped into two categories: activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). ADLs describe basic functions, including bathing and dressing. IADLs are tasks required for noninstitutional community living, such as housework, meal preparation, transportation to medical appointments and community services, and health management and maintenance.

Post-9/11 military caregivers perform fewer ADLs and IADLs than pre-9/11 and civilian caregivers, largely because their care recipients require less assistance with these types of tasks. When such help is required, most post-9/11 military caregivers help with these tasks. Nonetheless, civilian and post-9/11 military caregivers report spending roughly the same amount of time per week on caregiving, regardless of their era of service; however, those who serve as caregivers to a spouse spend the most time caregiving per week. Post-9/11 caregivers were more likely to report that they had to help care recipients cope with stressful situations or avoid triggers of anxiety or antisocial behavior.

How much time does caregiving demand? For all caregivers, this demand is substantial. In general, civilian caregivers tended to spend more time each week performing these duties than pre-9/11 military caregivers, though the time was comparable for post-9/11 military caregivers. Seventeen percent of civilian caregivers reported spending more than 40 hours per week providing care (8 percent reported spending more than 80 hours per week); for post-9/11 military caregivers and pre-9/11 military caregivers, 12 and 10 percent, respectively, spent more than 40 hours per week.

Caregiving Imposes a Heavy Burden

Caring for a loved one is a demanding and difficult task, often doubly so for caregivers who are juggling care duties with family life and work. The result is often that caregivers pay a price for their devotion. Military caregivers consistently experience worse health outcomes, greater strains in family relationships, and more workplace problems than non-caregivers, and post-9/11 military caregivers fare worst in these areas.

Military caregivers consistently experience poorer levels of physical health than non-caregivers. In addition, military caregivers face elevated risk for depression. We found that key aspects of caregiving contribute to depression, including time spent giving care and helping the care recipient cope with behavioral problems. Perhaps of even greater concern, between 12 percent (of pre-9/11 military caregivers) and 33 percent (of post-9/11 military caregivers) lack health care coverage, suggesting that they face added barriers to getting help in mitigating the potentially negative effects of caregiving.

The impacts of caregiving on families are more pronounced among post-9/11 military caregivers, largely because of their age. Of all caregivers caring for a spouse, post-9/11 military caregivers report the lowest levels of relationship quality with the care recipient. This difference is largely accounted for by the younger age of post-9/11 military caregivers, but it still places these newer romantic partnerships at greater risk of separation or divorce.

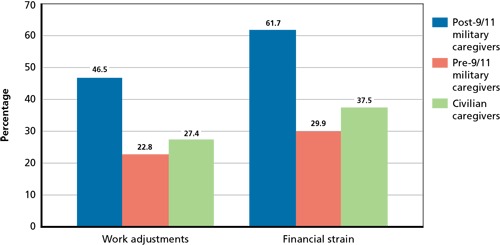

As noted earlier, the majority of military caregivers are in the labor force. Caregiving also has an effect on absenteeism. Civilian caregivers reported missing 9 hours of work on average, or approximately 1 day of work per month. By comparison, post-9/11 military caregivers report missing 3.5 days of work per month on average. The lost wages from work, in addition to costs incurred associated with providing medical care, result in financial strain for these caregivers (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Work and Financial Strain as a Result of Caregiving

NOTE: Percentage of caregivers who report making work adjustments and experiencing financial strain as a result of caregiving.

Most Relevant Programs and Policies Serve Caregivers Only Incidentally

Our environmental scan identified more than 100 programs that offer services to military caregivers (see the “Common Caregiving Services” section). However, most serve caregivers incidentally (i.e., caregivers are not a stated or substantial part of the organization's reason for existence, as evidenced by its mission, goals, and activities).

Figure 3 categorizes these programs according to the types of services (as described earlier in the “Common Caregiving Services” section) that each offers to caregivers. We found that 80 percent of these programs are offered by private, nonprofit organizations; 8 percent by private, for-profit organizations; and 12 percent by government entities.

Figure 3.

Number of Programs Supporting Military Caregivers Across Ten Areas

These programs tend to be targeted toward the care recipient, with his or her family invited to participate, or toward military and/or veteran families, of whom caregivers are a subset. These programs either make services available for family caregivers or they serve military families and within that group offer services for the caregiver subset. There are two primary reasons for this: First, most programs limit eligibility to primary family members. This limitation excludes caregivers who are either in the care recipient's extended family or are not related to the care recipient. Second, many of these programs are geared toward caregivers for older populations, and thus typically limit eligibility to those caring for someone age 60 or older. Post-9/11 caregivers—more than 80 percent of whom are under age 60—are hit particularly hard by this focus on older caregivers.

Of services targeted to caregivers, we examined the goals of the services provided, grouped them into four categories, and assessed their alignment with caregiver service use and needs, noting programmatic gaps in some areas.

Services helping caregivers to provide better care (patient advocacy or case management and structured education or training). More than 34 percent of post-9/11 caregivers reported difficulties because of medical uncertainty about the care recipient's condition; half that share of pre-9/11 and civilian caregivers reported such difficulties. We also found that post-9/11 caregivers reported greater challenges obtaining necessary medical and other services for their care recipients as compared with other caregivers. While many programs offered patient advocacy and case management support, only 20 to 30 percent of all caregivers were using this type of program. Among those who did, post-9/11 military caregivers rated them as significantly more helpful than did other caregivers.

Services addressing caregiver health and well-being (respite care, health and mental health care, structured social support, and structured wellness activities). We found that caregivers have consistently worse health outcomes than non-caregivers, and post-9/11 military caregivers' outcomes are consistently the worst among caregivers. Close to half of all post-9/11 military caregivers do not have such coverage, and only four programs specifically target caregivers in this area (12 offer some form of mental health care). Respite care is offered by only nine organizations, though notably fewer post-9/11 military caregivers (20 percent) have used respite care than civilian caregivers (29 percent). In contrast, more programs promote caregiver wellness via structured wellness activities (e.g., fitness classes, stress relief lessons, or outdoor physical activities) for caregivers and their families.

Services addressing caregiver and family well-being (structured wellness activities and a religious support network, and a “helping hand” [direct support, such as loans, donations, legal guidance, housing support, or transportation assistance]). To address the issue of lower-quality family relationships, religious programming and structured wellness activities are often geared toward families.

Services addressing income loss (financial stipend). Finally, only three stipend programs (primarily for post-9/11 caregivers or those who care for the elderly) exist to help offset income loss that results from caregiving. This seemingly important service helps address the financial challenges that caregivers report having and that may result from, among post-9/11 military caregivers, a largely employed group of caregivers who miss, on average, 3.5 days of work per month. However, among those who received a monthly stipend or caregiver payment from the VA, pre-9/11 caregivers rated it as significantly more helpful than did post-9/11 caregivers.

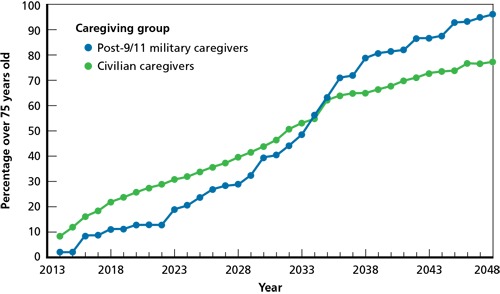

Caregivers Need Help with Future Planning

As younger caregivers age, the demographic composition of caregivers and the dynamic relationship between caregivers and care recipients will change, signaling the need for long-term planning. This need is likely more pronounced for post-9/11 military care recipients, who are younger and may be more vulnerable than pre-9/11 and civilian care recipients, particularly those relying on parents and aging spouses (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Projected Proportion of Post-9/11 Military and Civilian Caregivers Who Are Parents Over the Age of 75, 2013–2048

NOTE: One quarter of caregivers to post-9/11 veterans are parents. We project that in 15 years (in 2028), the proportion of these caregivers over the age of 75 will begin to increase substantially, resulting in the need to find alternative care for the veteran.

Critical aspects of planning include financial, legal, residential, and vocational/educational planning. Lack of knowledge about services available for aging care recipients, or being ill-informed about how to access such services, may hinder some caregivers from making future plans for their loved one, while the emotional toll that such planning takes may also affect caregivers' ability to make concrete future plans.

Few of the military caregiver–specific programs we identified offered specific long-term planning assistance to military caregivers. Beyond the usual advice for planning legal issues for the care recipient (powers of attorney, living wills, estates and trusts), there is little guidance to help military caregivers address long-term needs for themselves. Planning for the caregiver's own future can provide security for the care recipient's future as well, particularly if the caregiver becomes incapacitated by poor health or dies.

The Burden of Caregiving Affects Society

While the value of caregiving may be high for the care recipient and helpful for defraying medical care and institutionalization costs, the burden of caregiving exacts a more significant toll on the economy. As a consequence of the impact in the employment setting, as well as excess health care costs to tend to their own increased health needs, caregivers confer costs to society. Using literature from the civilian caregiving setting, as well as from studies on the effects of mental health problems on society, we estimate that the costs of lost productivity are $5.9 billion (in 2011 dollars) among post-9/11 caregivers.

To mitigate these costs over time, efforts to address the negative consequences and increased costs of caregiving can potentially increase the value that military caregiving confers on society. Future studies that gather more detailed information and data about the effectiveness of various caregiver support interventions and their impact on the costs of lost productivity (at both the individual and societal levels) might inform the business case for increasing support for this vulnerable population.

What Can Be Done: Recommendations

Ensuring the long-term well-being of military caregivers will require concerted and coordinated efforts to address the needs of military caregivers and to fill the gaps we have identified. To address these concerns, we make recommendations in four strategic areas.

Recommendations at a Glance

Empower caregivers

Create caregiver-friendly environments

Fill gaps in programs

Plan for future caregiving needs

Empower Caregivers

Efforts are needed to help empower military caregivers. These should include ways to build their skills and confidences in caregiving, mitigate the potential stress and strain of caregiving, and raise public awareness of the caregivers' value.

Provide high-quality education and training to help military caregivers understand their roles and teach them necessary skills. Training caregivers can help them play their roles more effectively and enhance the well-being of the wounded, ill, or injured veterans they are caring for.

Help caregivers get health care coverage and use existing structured social support. Ensuring that caregivers have health care coverage is critical to their continued health and well-being. Likewise, peer-based social support programs to address feelings of isolation are vital to improve caregiver connectedness and build supportive networks.

Increase public awareness of the role, value, and consequences of military caregiving. Public awareness or education will raise the profile of military caregivers and help ensure that their needs are addressed and their value recognized. This step may also help additional members of this group self-identify and seek support.

Create Caregiver-Friendly Environments

Creating contexts that acknowledge caregivers' special needs and status will help them play their roles more effectively and balance the potentially competing demands of caregiving and their own work lives.

Promote work environments that support caregivers. Provide protection from discrimination and promote workplace adaptations. While federal law offers protection from discrimination against caregivers in the workplace, practices and policies for accommodating caregivers' needs and improving support for caregivers in the workplace can reduce absenteeism and improve productivity. One example includes employee assistance programs, which can provide counseling support and referrals for additional resources.

Health care environments catering to military and veteran recipients should make efforts to acknowledge caregivers as part of the health care team. Military caregivers assume responsibilities to help maintain and manage the health of their care recipients. Performing these tasks effectively requires that they interact regularly with health care providers: physicians, nurses, and case managers. Health care providers can facilitate caregiver interaction with the health care system by acknowledging caregivers' key role in helping veterans navigate the system and providing necessary supplemental care.

Fill Gaps in Programs

As we noted, programs relevant to the needs of military caregivers are typically focused on the service member or veteran, and only incidentally related to the caregiver's role. In addition, we observed specific gaps in needed programs. Therefore, eligibility issues and specific programmatic needs should be addressed.

Ensure that caregivers are supported based on the tasks and duties they perform, rather than their relationship to the care recipient. Programs should extend eligibility to all caregivers who might benefit from them, including extended family and friends. Organizations that serve wounded, ill, or injured service members and veterans and who serve caregivers who are family members, or those that serve military and veteran families and serve caregivers who have also served, will need to consider how to expand eligibility to include extended and nonfamily caregivers. In addition, the most notable gaps in programmatic support were resources that connected caregivers with health care coverage (nearly one-third of post-9/11 caregivers lacked coverage) and financial support to compensate caregivers for income loss and other expenses.

Respite care should be made more widely available to military caregivers, and alternative respite strategies should be considered. To the extent that adverse outcomes associated with caregiving (e.g., depression) are influenced by time spent caregiving, finding temporary relief from caregiving appears critical. Respite for military caregivers should be considered carefully, and existing programs for patients with cancer, the frail/elderly, care recipients with dementia, or the physically disabled may need adaptation to better serve military care recipients.

Plan for the Future

Ensuring the long-term well-being of caregivers and the agencies that aim to support them may each require efforts to plan strategically for the future, not only to serve the dynamic and evolving needs of current military caregivers, but also to anticipate the needs of future military caregivers in a changing political and fiscal environment. Planning for the future will require that efforts to support caregivers address the following:

Encourage caregivers to create financial and legal plans to ensure caregiving continuity for care recipients. Organizations that serve military caregivers can fill a gap in services by creating and sharing guidance about long-term financial and legal planning. Programs that are available in these areas typically address the needs of those caring for the elderly or for persons with dementia and Alzheimer's, focusing expectedly on retirement and estate planning. Planning for post-9/11 care recipients needs to be different. These plans need to address financial stability for caregivers and their families and may include strategies to make up for lost wages and retirement and pension benefits. These plans also need to factor in the financial stability of the care recipient, who may need resources to buy caregiver support if the current caregiver is unable to continue in that role. Legal plans need to prepare powers of attorney and executors for estates or trusts, and may also require that new guardians and caregivers be appointed in the event that the current primary caregivers are no longer available.

Enable sustainability of programs by integrating and coordinating services across sectors and organizations through formal partnership arrangements. The large number of current organizations raises two sustainability issues. First, if services are not coordinated, they can become a “maze” of organizations, services, and resources in which caregivers can become overwhelmed (Tanielian et al., 2013). Second, attention and commitment for supporting veterans and their families is currently high, but public interest may fade in future years, potentially translating into decreases in the level of private and philanthropic support for the many nongovernment programs (Carter, 2013; McDonough, 2013). One way to address both issues is to create formal partnerships across organizations. Effective partnerships will require exploring opportunities for true coordination, including the creation of coalitions.

Foster caregiver health and well-being through access to high-quality services. High-quality support services are needed to boost caregiver effectiveness and reduce the negative effects of caregiving. The Institute of Medicine (National Research Council, 2001) has defined high-quality medical care as care that is effective, safe, caregiver-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. This definition applies to support programs as well. At present, however, little is known about the quality or effectiveness of available military caregiver programs. High-quality programs are important because research has shown that quality care can improve outcomes. Understanding the quality of services requires measuring and assessing the structure, process, and outcomes associated with these services. Evaluating all of the identified programs in our scan was beyond our scope. But we also did not hear of caregiver support programs conducting rigorous evaluations or studies to document their effectiveness, or that they had implemented continuous quality improvement initiatives. Currently, the Family Caregiver Alliance and Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving maintain databases on evidence-based programs, and the Family Caregiver Alliance resource includes information about model programs and emerging practices. In addition, the VA is funding research projects to assess the effectiveness of caregiver services and interventions. Organizations that implement military caregiver programs could benefit from using these resources to inform their own service delivery. Over the long term, demonstrating program value may require that organizations also evaluate the extent to which their services are improving outcomes for participants.

Invest in research to document the evolving need for caregiving assistance among veterans and the long-term impact of caregiving on the caregivers. This study provides a snapshot of the needs and burdens of military caregiving. While we can provide a glimpse into the future of military caregiving by looking at the characteristics of post-9/11 caregivers and the factors that might affect their caregiving demands, we can only make projections. Similarly, while the needs of pre-9/11 veterans may be what post-9/11 veterans will eventually require, there are differences in the make-up and expectations of the pre-9/11 and post-9/11 generations. In the future, additional rigorous, cross-sectional research like ours can shed light on the needs of caregivers and how their needs compare to those presented here. In addition, longitudinal studies and evaluations are needed to document changing needs over time and the effectiveness of programs and services intended to meet those needs.

The Bottom Line

Military caregivers play an essential role in caring for injured or wounded service members and veterans. This enables those for whom they are caring to live better quality lives and can result in faster and improved rehabilitation and recovery. Yet playing this role can impose a substantial physical, emotional, and financial toll on caregivers. Improving military caregivers' well-being and ensuring their continued ability to provide care will require multifaceted approaches to reduce the current burdens caregiving may create and to bolster their ability to serve as caregivers more effectively. Given the systematic differences among military caregiver groups, it is also important that tailored approaches meet the unique needs and characteristics of post-9/11 caregivers.

Footnotes

This summary was prepared as part of a research study funded by Caring for Military Families: The Elizabeth Dole Foundation. The research was conducted within RAND Health in coordination with the RAND National Security Research Division, divisions of the RAND Corporation.

References

- Carter, P., Expanding the Net: Building Mental Health Care Capacity for Veterans, Washington, D.C.: Center for a New American Security, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, J., “Strengthening and Transforming Local Partnerships to Serve Veteran Families,” in VAntage Point: Dispatches from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2013. As of January 5, 2014: http://www.blogs.va.gov/VAntage/11496/serve-veteran-families/

- National Research Council, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramchand, Rajeev, Tanielian Terri, Fisher Michael P., Anne Vaughan Christine, Trail Thomas E., Epley Caroline, Voorhies Phoenix, Robbins Michael William, Robinson Eric, Ghosh-Dastidar Bonnie, Hidden Heroes: America's Military Caregivers, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, RR-499-TEDF, 2013. As of January 5, 2014: http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR499.html [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanielian, T., Ramchand R., Fisher M. P., Sims C. S., Harris R., and Harrell M. C., Military Caregivers: Cornerstones of Support for Our Nation's Wounded, Ill, and Injured Veterans, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, RR-244-TEDF, 2013. As of January 5, 2014: http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR244.html [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]