Abstract

Prowashonupana barley (PWB) is high in β-glucan with moderate content of resistant starch. PWB reduced intestinal fat deposition (IFD) in wild type Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans, N2), and in sir-2.1 or daf-16 null mutants, and sustained a surrogate marker of lifespan, pharyngeal pumping rate (PPR), in N2, sir-2.1, daf-16, or daf-16/daf-2 mutants. Hyperglycaemia (2% glucose) reversed or reduced the PWB effect on IFD in N2 or daf-16/daf-2 mutants with a sustained PPR. mRNA expression of cpt-1, cpt-2, ckr-1, and gcy-8 were dose-dependently reduced in N2 or daf-16 mutants, elevated in daf-16/daf-2 mutants with reduction in cpt-1, and unchanged in sir-2.1 mutants. mRNA expressions were increased by hyperglycaemia in N2 or daf-16/daf-2 mutants, while reduced in sir-2.1 or daf-16 mutants. The effects of PWB in the C. elegans model appeared to be primarily mediated via sir-2.1, daf-16, and daf-16/daf-2. These data suggest that PWB and β-glucans may benefit hyperglycaemia-impaired lipid metabolism.

Keywords: obesity, barley, animal models, insulin sensitivity, aging

1. Introduction

Obesity costs the US health care system over $100 billion a year and predisposes to diabetes which generates even higher costs (Ogden et al., 2006). Only limited medications are available to treat obesity, and surgical treatments are second-line obesity treatments. Diet intervention, exercise, and lifestyle modification have been promoted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and other government institutions, but sustainable weight loss has been elusive. In an intensive diet and behaviour modification program with meal replacements, adults lost 22.6–25.5+1% of their body weight temporarily, but maintained only a 5% weight loss after 3 years (Kress, Hartzell, Peterson, Williams, & Fagan, 2006; Wadden & Frey, 1997).

Daily consumption of non-digestible fibre may offer a strategy to increase energy expenditure and reduce body fat by stimulation of mitochondrial fat oxidation (Chandrasekara & Shahidi, 2011; John & Shahidi, 2010; Madhujith, Amarowicz, & Shahidi, 2004). Average daily consumption of dietary fibre in the United States is currently 3 to 10 g/day, 4 to 13 fold less than recommended (Anderson & Akanji, 1991; Goldring, 2004). Non-digestible carbohydrate, fermented to short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in the lower gastrointestinal tract, increases satiety hormone peptides YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). These hormones augment fat oxidation (lower respiratory quotient), elevate energy expenditure (Keenan et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2008), and inhibit body fat accretion in rodents (Keenan et al., 2006; Shen et al., 2009). The most efficient SCFA, butyrate, stimulates the production of PYY, GLP-1 (Zhou et al., 2006) and prevents diet-induced insulin resistance which is directly related to a shorter lifespan in mice, a reduced cell survival, and a decreased lifespan in the Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) model organism (Abate & Blackwell, 2009; Gao et al., 2009). A diet supplemented with β-glucans at 4g/day for 14 weeks in 7 healthy overweight and obese subjects increased fasting PYY, GLP-1, and increased post-meal satiety in humans (Greenway et al., 2007). We found that fermentable carbohydrate or resistant starch (RS), endogenous gut fermentation products of rodents fed RS, or the exogenous SCFA, butyrate, all reduce intestinal fat deposition (IFD) in the wild type C. elegans (N2) (Zheng et al., 2010). The lipid oxidation pathway including cluster differentiation transport protein (CD36), carnitine palmitoyltranferase-1 (CPT-1), acetyl co-enzyme A carboxylase (ACC), and acetyl CoA synthetase ACS have been identified using genetically manipulated C. elegans (see review (Zheng & Greenway, 2012)).

Barley is the fourth most important cultivated foodstuff, and contains 62–77% starch (w/w) which is composed of 25–35% atypical amylose starch with 3–5% RS type 3 (RS3) and β-glucan (Asare et al., 2011; Vasanthan & Bhatty, 1998), a mixture that provides a distinctive amylose-amylopectin interaction (Behall, Scholfield, & Hallfrisch, 2005; Dongowski, Huth, Gebhardt, & Flamme, 2002; Lifschitz, Grusak, & Butte, 2002; Rendell et al., 2005; Tang, Ando, Watanabe, Takeda, & Mitsunaga, 2001). Barley also contains high levels of functional lipids, such as, total phytosterols (1.2–9.6% of barley oil) and total tocotrienols (0.3–0.6% of barley oil) which are 6–12 fold higher than in palm oil (0.05%) and 4–8 fold higher than in rice bran oil (0.08%) (Moreau, Flores, & Hicks, 2007). The barley variety Prowashonupana (PWB) contains 17% β-glucan and 15% fermentable starch (Rendell et al., 2005). These carbohydrates delay or decrease the absorption of dietary fats and lower the postprandial glycaemic response (Lifschitz et al., 2002). Dietary fermentable fibre such as RS is present in a variety of cereals and offers the opportunity to reduce body fat and control body weight. We demonstrated that RS type 2 (RS2) from corn (Ingredion Incorporated, Westchester, IL, USA) induced a 23% reduction of intestinal fat deposition in wild type C. elegans (Zheng et al., 2010). The specific PWB used in the present study has a lower RS content compared to high amylose corn starch, but has significantly more soluble β-glucan than most other barleys, which are linked to half of the PWB fibre (Behall et al., 2005; Rendell et al., 2005). Retrograded amylose starch, RS type 3 (RS3), and β-glucan of PW barley provide distinctive amylose–amylopectin and amylopectin-β-glucan interactions that increase the viscosity and delay energy absorption in the GI tract (Asare et al., 2011; Moreau et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2001; Vasanthan & Bhatty, 1998) reducing the glycaemic peak by 50%, lowering low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in healthy humans, decreasing fat accumulation in humans and rodents (Wursch & Pi-Sunyer, 1997), augmenting immunity by activating the dectin-1 receptor and activating multiple genetic signalling pathways, including the DAF-2/insulin-like receptor (ILR) pathways. The details of the mechanism by which insulin-resistance is improved, however, are unclear (Engelmann & Pujol, 2011; Tsoni & Brown, 2008).

C. elegans is a small, free-living soil nematode, a multicellular eukaryotic organism, distributed widely around the world. C. elegans is the first animal to have its genome completely sequenced and conserves 65% of the genes associated with human disease (Zheng & Greenway, 2012). C. elegans dauer formation (daf) gene, daf-2, is a homolog of the insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor in humans and is the only gene encoding the insulin/IGF-1 like receptor in C. elegans (Zheng & Greenway, 2012). Decreased daf-2 signalling increases C. elegans lifespan (Koga, Take-uchi, Tameishi, & Ohshima, 1999; Kramer, Davidge, Lockyer, & Staveley, 2003) which fully depends upon daf-16 (Patel et al., 2008), since daf-16 null mutations completely suppress the extension of lifespan by daf-2 (e1370)III null mutant (Burks et al., 2000; Hertweck, Gobel, & Baumeister, 2004; Hunt et al., 2011; Tissenbaum & Ruvkun, 1998; Yu et al., 2010). Hyperglycaemia (2% glucose) causes insulin resistance in N2 and daf-2(e1370)III null mutants, and reduces pharyngeal movement, a surrogate marker directly related to lifespan (Abate & Blackwell, 2009). sir-2.1 overexpression prolongs C. elegans lifespan (Frojdo et al., 2011). In fact, doubling C. elegans sir-2.1 gene number induces a 50% increase in the lifespan that is DAF-16/FOXO dependent (Dorman, Albinder, Shroyer, & Kenyon, 1995; Tissenbaum & Guarente, 2001), and the null mutant of sir-2.1(ok434)IV has a shorter lifespan than the N2 (Gami & Wolkow, 2006), which recently became controversial, because RNA interference (RNAi) did not suppress the longevity (Burnett et al., 2011). The gcy-8 gene (thermotaxis) is a subtype of guanylyl cyclase (GCYs) which has been proven to promote fat storage and mediate satiety, as does cck.

Two thirds of the genes associated with human diseases have homologs in C. elegans, and the C. elegans intestine has similarities to the human gastrointestinal track (You, Kim, Raizen, & Avery, 2008). Over 300 genes have been shown to cause a reduction in body fat when inactivated, and inactivation of more than 100 genes has shown an increased fat storage (Ashrafi et al., 2003). The genes governing lipid metabolism do not necessarily overlap with genes governing the aging process (Zheng & Greenway, 2012). Not only does the C. elegans model organism offer reduced costs when screening for bioactive substances, the translucent bodies of the worms are convenient for analysis of intestinal fat deposition (IFD) by lipid—staining dyes. Nile red fluorescent dye has been validated through lipid-extraction, separation with thin layer chromatography, and quantification with gas chromatography (Ashrafi et al., 2003). Recently, Nile red staining in vitro has been recommended as being superior to coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) microscopy (Yen et al., 2010).

The goal of the current study was to determine the effects of PWB on IFD, insulin-resistance, and hyperglycaemia-impaired lipid metabolism using the C. elegans N2, and null mutants, sir-2.1(ok434)IV, daf-16(mgDf50)I, or daf-16(mgDf50)I;daf-2(m65) III. Pharyngeal pumping rate (PPR), a surrogate marker of C. elegans lifespan (Chow, Glenn, Johnston, Goldberg, & Wolkow, 2006; Finley et al., 2013), was also monitored to determine effect of PWB on lifespan.

2. Material and methods

C. elegans strains and their standard lab food source, Escherichia coli (E. coli, OP50, Uracil auxotroph), were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The C. elegans model is not regulated by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) nor does it require IACUC approval (Zheng et al., 2013).

2.1 Culture of E. coli (OP50)

OP50 were cultured by the standard method described elsewhere (Zheng et al., 2010). Briefly, 10µl± of stock E. coli solution was added to Luria Broth (LB) medium and the medium was incubated at 37°C for 48h. The OP50 were then sub-cultured in Petrifilm™ E.coli/Coliform Count Plates (3M Corporate, Minneapolis, MN, USA) at 37°C for 24h, and the colonies of OP50 were confirmed to be at a density of 5×108 – 5×1011cfu/ml at which time the C. elegans were allowed to eat ad libitum.

2.2 Culture of C. elegans

C. elegans N2, sir-2.1(ok434)IV, daf-16(mgDf50)I, and daf-16(mgDf50)I;daf-2(m65)III null mutants were used in this study. Each strain was age synchronized, grown on Nematode Growth Media (NGM) agar plates (Ø35 mm), transferred to a new dish every other day, and stored in a low temperature incubator (Revco Tech., Nashville, NC, USA) at 20°C or 15°C (daf-16(mgDf50)I;daf-2(m65)III) throughout the experiments. Mature gravid C. elegans were transferred individually onto the agar plates and treated with a lysis solution consisting of NaOH (1M, 500 µl, v/v) and sodium hypochlorite solution (5.25% , 200 µl, v/v) to dissolve the C. elegans body and to release the viable eggs. Stock solutions have been previously described in detail. One day prior to the experiment, 200µl of a feeding media containing E. coli was added to the agar dish.

2.3 Diet composition

Prowashonupana barley (Sustagrain®, Ardent Mills Corporate, Denver, CO, USA) were powdered using a centrifugal mill with a 0.75mm sieve (Retsch ZM 200; Haan, Germany), autoclaved at 121°C, and suspended in distilled deionized water (DDH2O; 5%, w/v). Detailed nutritional data of PWB by Ardent Mills Corporate is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Nutritional data of Prowashonupana barley (Sustagrain® Barley1), reported on a 100g basis.

| Content | Quantity (g) | Content | Quantity (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calories | 390 kCal | Vitamin A | 0 IU |

| Calories from Fat | 60 kCal | Vitamin C | 0 |

| Fat | 6.5 | Sodium | 12 |

| Saturated Fat | 1.8 | Calcium | 33 |

| Cholesterol | 0 | Iron | 3.6 |

| Carbohydrates | 64.3 | Vitamin B1 (Thiamin) | 0.6 |

| Total Dietary Fiber | 30 | Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) | 0.3 |

| Beta glucan | 15 | Vitamin B3 (Niacin) | 4.6 |

| Soluble Fiber | 12 | Potassium | 452 |

| Protein | 18 | Zinc | 2.8 |

Control animals were fed with OP50 only. The experimental groups larval stage 2 (L2) were fed supplementary Prowashonupana barley (PWB, 0.5, 1.0, or 3.0%) that had no additives. To create insulin resistance, two percent glucose was added to an additional group of each strain, with and without PWB (Table 2). The dietary nutrient composition is listed in Table 3 (Feijo Delgado et al., 2013). C. elegans were transferred to fresh dishes every other day receiving treatment (50µl).

Table 2.

Protocol of experiment

| Treatments (50µl) |

Dosage (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without glucose |

With glucose |

|||||||

| 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 3 | |

| OP50 (2×109 cfu/ml, µl) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| PWB (5%, µl) | 0 | 5 | 10 | 30 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 30 |

| Glucose (50%, µl) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Table 3.

Diet ingredient composition

| Nutrients | PWB diet (mg/ml) | OP50 (mg/ml) | PWB treatment (mg/plate) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.5% | 1% | 3% | |||

| Beta-glucan | 150 | - | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.023 | 0.069 |

| Total dietary fiber | 300 | - | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.037 | 0.110 |

| Carbohydrate | 643 | 7.5 | 0.375 | 1.983 | 3.590 | 10.020 |

| Protein | 180 | 37.5 | 1.875 | 2.325 | 2.775 | 4.575 |

| Fat | 65 | 5.0 | 0.250 | 0.413 | 0.575 | 1.225 |

2.4 Pharyngeal movement (pumping rate, PPR)

Animals were examined periodically using a stereomicroscope (Nikon SMZ1500, Melville, NY, USA) with transmitted light. The pharyngeal pumping rate (PPR) was recorded manually by independent observers and the animals were returned to the incubators.

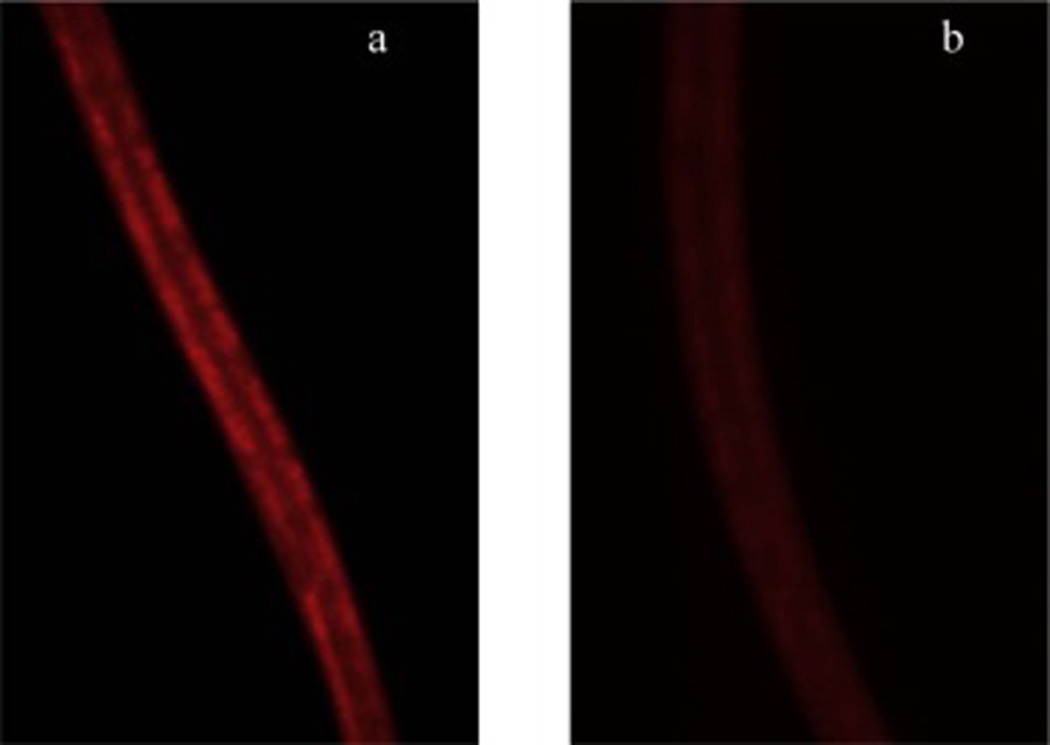

2.5 Fluorescence microscopy

The lipophilic dye, Nile red, was selected to stain the intestinal fat deposition. Prior to fixing the animals, an S-basal (see below) solution was added to the dish to wash the animals. The solution containing the animals was centrifuged for 20 seconds at 805G and this procedure was repeated twice. Animals were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde over 2h at 4°C and washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 5 min × 3. Nile red (50 µl) was applied to the specimens for 10 min. Ten microliters of Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotechnology Associates, AL, USA) was applied to a glass slide followed by 20µl of the medium containing Nile red stained animals. A cover glass was mounted on the glass slide. The slides were viewed with an epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse, Ti) equipped with a Texas Red filter. Fluorescent micrographs were taken with a digital camera (Andor, DU-885k, Concord, MA, USA). The micrographs were analyzed using NIS elements (Nikon). Line profiles of the optical densities (arbitrary units, % of control) of Nile red labelled IFD were determined for adult animals (larval stage 4 [L4]).

2.6 Quantitative RT-PCR

2.6.1 Reagents

The Trizol® reagent (T9424), chloroform (C2432), and isopropanol (I9516) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Taqman PCR core kit (N8080228), MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (N8080018), and RNase Inhibitor (N8080119) were obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA). RNase-free micro tubes and pipette tips were used in isolating RNA and in quantitative RT-PCR.

2.6.2 RNA isolation

Total RNA was extracted using the Trizol® reagent as described elsewhere (Ye, Gao, Yin, & He, 2007). C. elegans samples were homogenized in 1ml Trizol® Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) per 50–100 mg of tissue. The samples went through 5 freeze-thaw cycles in which they were frozen in liquid nitrogen and thawed in a 37°C water bath. The homogenized samples were vortexed at room temperature to allow the complete dissociation of nucleoprotein complexes. Two hundred microliters of cold pure chloroform per 1ml of Trizol® reagent were added and the samples were vortexed for 15s before being incubated at room temperature for 5min. The samples were centrifuged at 12,000g for 10 min at 4°C, and the top aqueous phase were transferred to a fresh tube. A 600µl aliquot of cold isopropanol per 1ml of Trizol® reagent was used for the initial homogenization. The samples were then incubated at room temperature for 10min, vortexed for 15s, and centrifuged at 12,000g for 10min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and the RNA pellet was washed once with 1ml cold 75% ethanol. The sample was vortexed and centrifuged at 7,500g for 5min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed completely and the RNA pellet was briefly air-dried. The RNA pellet was re-suspended in 0.1% diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water and stored at −80°C. The RNA concentration was analysed with a Nanodrop® ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Wilmington, DE, USA).

2.6.3 Quantitative RT-PCR

The mRNA levels of ckr-1, gcy-8, cpt-1, and cpt-2 were determined using Taqman® quantitative RT-PCR. The following components were added in one-step RT-PCR: 2.2µl H2O, 1µl 10× Taqman® buffer A, 2.2µl 25mM MgCl2 solution, 0.3µl 10mM dATP, 0.3µl 10mM dCTP, 0.3µl 10mM dGTP, 0.3µl 10mM dUTP, 0.05µl 20U/µl RNase inhibitor, 0.05µl 50U/µl MuLV reverse transcriptase, 0.05µl 5U/µl Amplitaq gold®, 0.25µl Taqman® probe and primers, and 3µl 5ng/µl RNA. The PCR reaction was conducted in triplicate using a Taqman® probe and primers set (Life Technologies) for ckr-1(Ce02408606_m1), gcy-8(Ce02456184_g1), cpt-I(Ce02440434_m1), and cpt-2(Ce02459919_g1). The mRNA signal was normalized over a eukaryotic 18S rRNA (Hs99999901-s1) internal control. The reaction was conducted using a 7900 HT Fast real-time PCR system (Life Technologies). Reverse transcription was done at 48°C for 30min, and AmpliTaq gold® activation (denaturation) was done at 95°C for 10min. Amplification of the DNA involved 40 cycles of 15s at 95°C and 1min at 60°C. Data was analyzed using the Sequence Detector Software (Life Technologies). The relative quantification of gene expression (2−ΔΔCt) was calculated.

2.7 Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean ± sem. Student t-test, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for IFD, analysis of co-variance (ANCOVA) was used to compare the slopes of PPR data, and principal component analyses (PCA) was conducted using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was set at P≤0.05.

3. Results

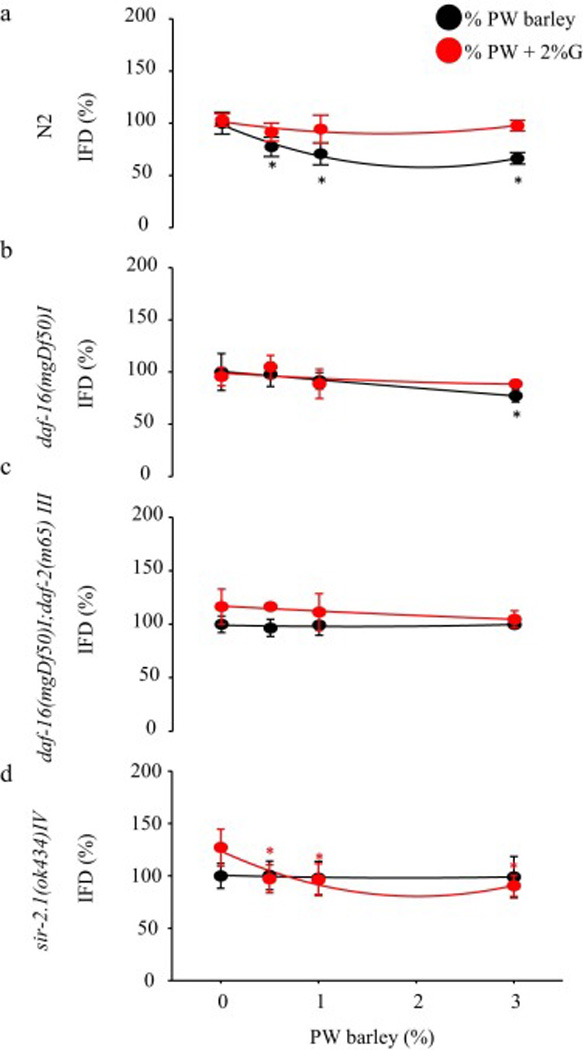

Changes of IFD indicated by fluorescent intensity of Nile red and alterations in lifespan suggested by reduced PPR indicating aging, with or without 2% glucose, were quantified in this study. The IFD was reduced in N2, and null mutants of sir-2.1(ok434)IV and daf-16(mgDf50)I. These reductions were reversed in the presence of 2% glucose. The PPRs declined in all groups as the animals aged. PWB treatment, however, increased the PPR in all groups compared to their control that did not receive PWB treatment. These responses were reversed in the presence of 2% glucose.

3.1 Intestinal fat deposition (IFD)

Post PWB treatment, the fluorescence intensity of Nile Red was dose-dependently reduced by 19 to 44% (0.5 or 3.0%, n=6, P<0.05) in N2 (Fig. 1), by 18 to 28% (0.5, 1.0, or 3.0%, n=9, P<0.01) in daf-16(mgDf50)I (Fig. 2b), or by 18 to 36% (0.5, 1.0, or 3.0%, n=9, P<0.01) in the sir-2.1(ok434)IV (Fig. 2d). The reduction in daf-16(mgDf50)I or sir-2.1(ok434)IV was reversed in presence of 2% glucose (Fig. 2b and 2d). In daf-16(mgDf50)I;daf-2(m65) III, only in presence of 2% glucose, PWB (0.5 or 3.0%) induced a 40–50% reduction of the fluorescence intensity in a dose-dependent manor (n=3, P<0.05) (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 1.

Intestinal fat deposition (IFD) was significantly reduced in the C. elegans (N2) that received the Prowashonupana barley (PWB, 0.5% or 3%) compared to a control group. a) IFD stained by Nile red in control animals. b) IFD stained by Nile red in animals that received the PWB (0.5% or 3%). c) Fluorescence intensity of Nile red was reduced in the PWB treated animals. d) The effect of PWB on fluorescence intensity of Nile red reduction was reversed in the presence of 2% glucose.

Fig. 2.

Intestinal fat deposition (IFD) was reduced in mutant C. elegans. a) N2 Fluorescence intensity of Nile red was reduced in the Prowashonupana barley (PWB, 0.5%, 1%, or 3%) treated animals. The fluorescence intensity of Nile red reduced by PWB treated animals was reversed in the presence of 2% glucose. b) daf-16(mgDf50)I: The fluorescence intensity of Nile red reduced by PWB treated animals was no different compared with control animals with or without glucose. c) daf-16(mgDf50)I;daf-2(m65)III: Fluorescence intensity of Nile red was not reduced in the PWB (0.5% or 3%) treated animals. PWB treatment reduced Nile red fluorescence intensity in the presence of 2% glucose. d) sir-2.1(ok434)IV: Fluorescence intensity of IFD stained by Nile red in animals that received the PWB (0.5%, 1%, or 3%).

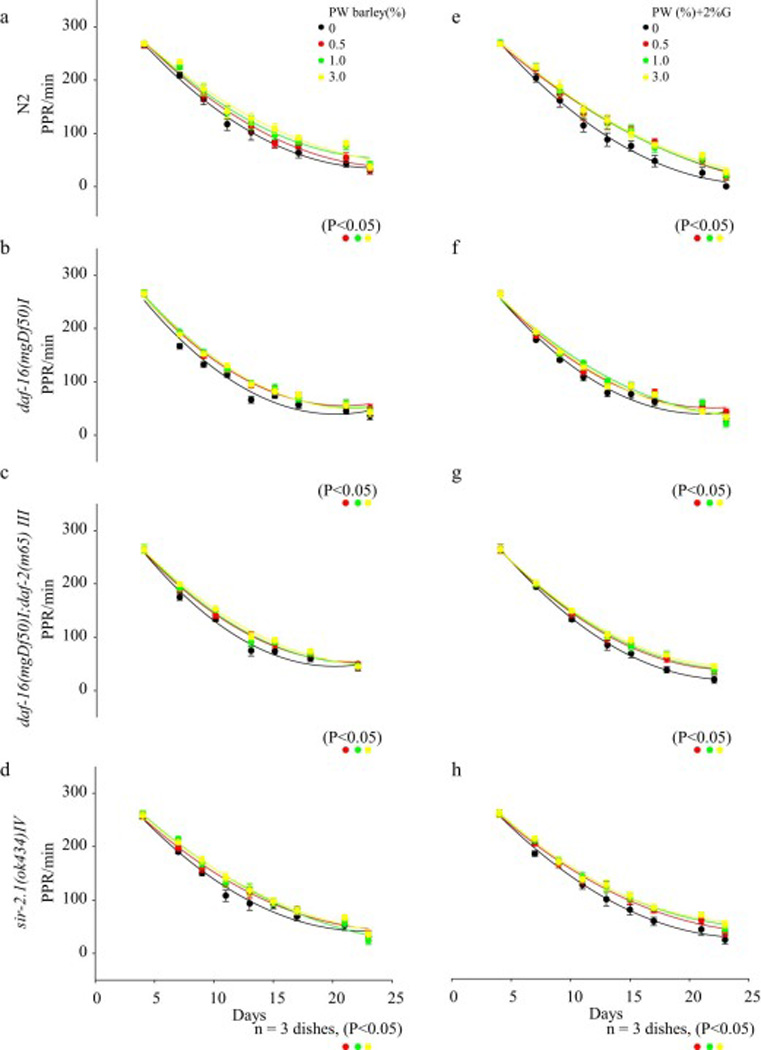

3.2 Pharyngeal pumping rate (PPR)

The PWB treatment dose-dependently elevated the PPR in N2 (0.5, 1.0, or 3.0%, P<0.05) (Fig. 3a, 3e), daf-16(mgDf50)I (Fig. 3b, 3f), daf-16(mgDf50)I;daf-2(m65)III (Fig. 3c, 3g), or sir-2.1(ok434)IV (Fig. 3d, 3h) (n=20animals/3 dishes, P<0.05) with or without additional 2% glucose.

Fig. 3.

Pharyngeal pumping rate (PPR) of C. elegans was reduced in all groups with aging. An elevation of the PPR was observed in animals that received the Prowashonupana barley (PWB) in a) N2 (P<0.05), b) daf-16(mgDf50)I groups (P<0.05), c) daf-16(mgDf50)I;daf-2(m65) III (P<0.05) or d) sir-2.1(ok434)IV (P<0.05). Similar results were observed in the presence of glucose in e) N2 (P<0.05), f) daf-16(mgDf50)I groups (P<0.05), g) daf-16(mgDf50)I;daf-2(m65) III (P<0.05) or h) sir-2.1(ok434)IV (P<0.05).

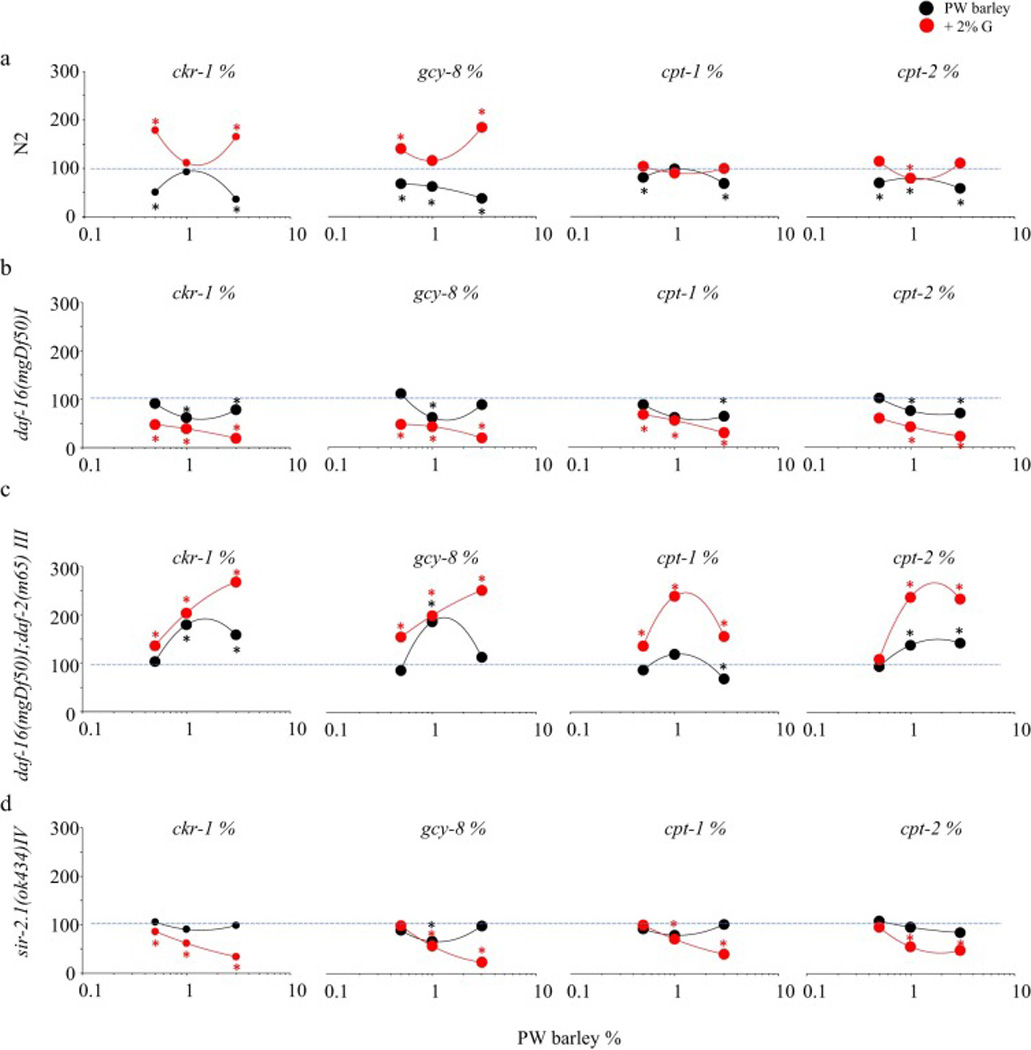

3.3 Lipid metabolism gene expression

PWB feeding (0.5, 1, and 3%) dose-dependently reduced mRNA expression of cpt-1 (20–30%), cpt-2 (30–40%), ckr-1 (30–40%), and gcy-8 (30–50%) in N2. The reduction was observed in daf-16 deficient mutant as cpt-1 (30%), cpt-2 20–30%, ckr-1 (40%), and gcy-8 (40%). In daf-16/daf-2 mutant, cpt-1 was reduced by 30% while other three mRNA expressions were elevated by cpt-2 (50%), ckr-1 (70–60%), and gcy-8 (80%). Although there was a 20% reduction in gcy-8, feeding did not change the other three mRNA expressions in the sir-2.1 mutant. In presence of glucose, however, these mRNA expressions were increased in N2 by 10% and in the mutant daf-16 by 40%, while mRNA expression was reduced in the mutant sir-2.1 by 50% after an initial increase of 30% and in the daf-16/daf-2 by 10–50% after an initial reduction of 40–60% (P<0.05, Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Prowashonupana barley (PWB) dose-dependently altered mRNA expressions of cpt-1, cpt-2, ckr-1, and gcy-8 in the C. elegans model. a) Reduced in N2 and was reversed by additional glucose; b) Elevated in daf-16 mutant with reduction on cpt-1 with further augmentation by glucose; and c) Decreased in daf-16/daf-2 mutant and further reduced by glucose with an initial increase except cpt-1; d) Did not change in sir-2.1 mutant while further reduced in presence of glucose.

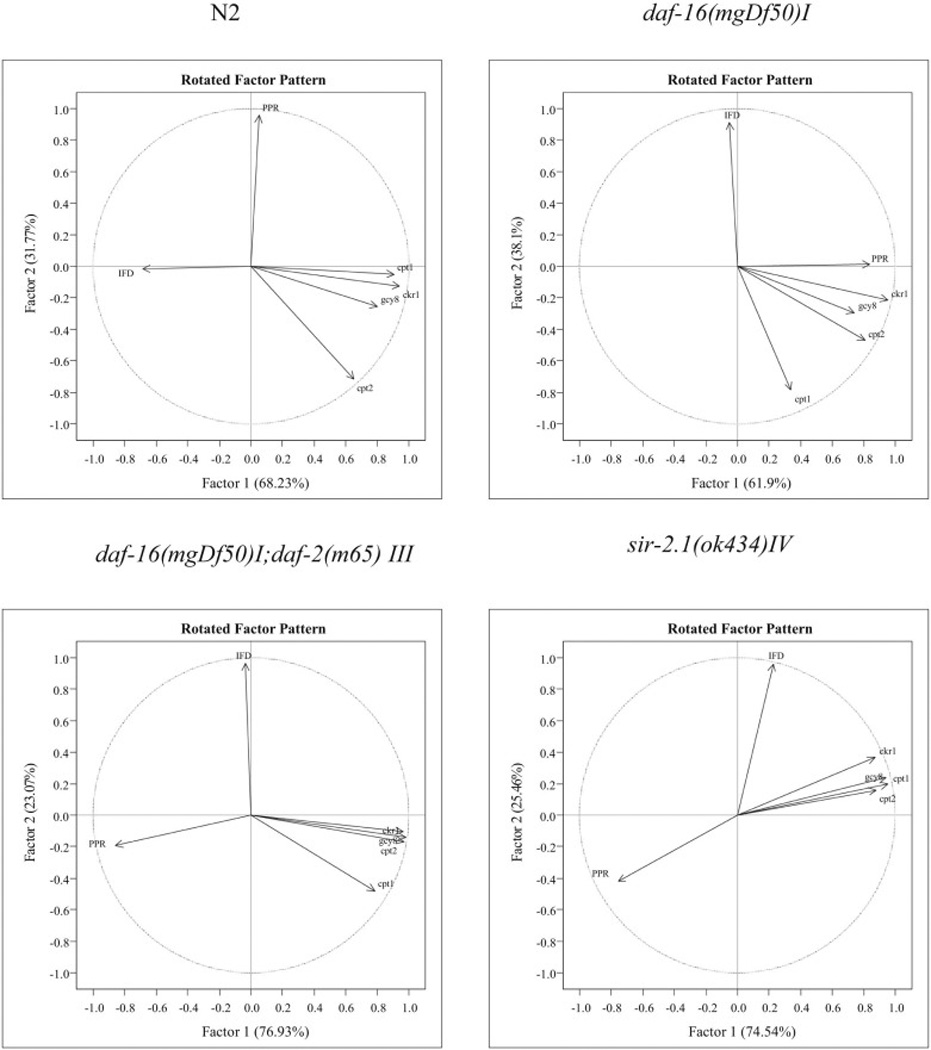

3.4 Principal component analyses (PCA)

Two factors explained the results of PCA. IFD has a strong negative effect with factor 1 in N2, while it has weak relationship with factor 1 in other strains. IFD has a strong positive relationship with factor 2 in daf-16, daf-16/daf-2, and sir-2.1 null mutants. PPR slope has a strong negative relationship with factor 2 in daf-16/daf-2, and sir-2.1 null mutants, but there was a strong positive relationship with factor 1 in daf-16 mutant. IFD and PPR have an inverse relationship in all strains. cpt-1, ckr-1, gcy-8, and cpt-2 have strong positive relationship with factor 1 but these 4 genes have an indirect relationship with factor 2 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Principal component analyses (PCA) showed the relationships of the lipid metabolic related mRNAs (ckr-1, cpt-1, cpt-2, and gcy-8), pharyngeal pumping rate (PPR) slope, and intestinal fat deposition (IFD) with two strong factors.

4. Discussion

PWB (3%) induced significant reductions of Nile Red fluorescent intensity representing intestinal fat deposition (IFD) in N2 (40%), sir-2.1(ok434)IV (30%) and daf-16(mgDf50)I (25%) deficient mutants, but not in the daf-16(mgDf50)I;daf-2(m65)III deficient mutant. The pharyngeal pumping rate (PPR) was elevated with all varieties of animals fed PWB. On the contrary, reduced fluorescence intensity and elevated PPR were detected in daf-16/daf-2(m65)III deficient mutant in the presence of an additional 2% glucose. PWB reduced cpt-1, cpt-2, ckr-1, and gcy-8, which was reversed in sir-2.1 deficient mutant suggesting that the major pathway of this effect is mediated by sir-2.1. It appeared that glucose reversed the effect of PWB in the N2. Dissimilarly, daf-16 deficient had only a reduction of cpt-1 with elevations on cpt-2, ckr-1, and gcy-8, all of which had an initial reduction. Additional glucose augmented the PWB effects to a greater degree than in N2. Thus, daf-16 seemed playing an inhibitory role on lipid and glucose metabolism. PWB had similar effects in daf-16/daf-2 mutant as in N2. Unlike N2, the effect of additional glucose in daf-16/daf-2 mutant was eliminated by an initial increase in cpt-2, ckr-1, and gcy-8 followed by further reduction. These findings indicated that daf-2 mediated the PWB effect but to a lesser degree than sir-2, and facilitated glucose metabolism.

Hyperlipidaemia is often co-existent with hyperglycaemia. Insulin-resistance induces hyperglycaemia in rodent diabetes due to an increased peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-α (PPARα) (Hostetler, Huang, Kier, & Schroeder, 2008). Deletion of nuclear hormone receptor-49 (nhr-49), a homologue of PPARα in C. elegans, prevents hyperlipidaemia and restores insulin-sensitivity comparable to that seen in PPARα null mice (Atherton, Jones, Malik, Miska, & Griffin, 2008). In the current study, the PWB (3.0%) induced more than a 40% reduction in the IFD, which was daf-16 or sir-2.1 dependent since the effect was not seen in the daf-16/daf-2 mutant. The effect of reducing or not reducing insulin sensitivity in the treatment groups described above was reversed when decreased insulin-sensitivity was created by excessive glucose, and produced IFD reduction in daf-16/daf-2 mutant insulin-resistance model. Since daf-16 has a central role in mediating the downstream insulin signalling pathways and is the major target of the daf-2 pathway which negatively regulates daf-16 (Kenyon, Chang, Gensch, Rudner, & Tabtiang, 1993; Lee, Murphy, & Kenyon, 2009), possibly, PWB/β-glucans indirectly affected insulin-sensitivity by affecting hyperglycaemia impaired lipid metabolism and served as a unique functional food in addition to providing a source of RS. daf-2 is the only gene that encodes the insulin/IGF-1 like receptor in C. elegans and the genes governing lipid metabolism do not necessarily overlap with genes governing the aging process (Zheng & Greenway, 2012). We found that neither sir-2.1 nor daf-16 was required for the PWB diet to reduce IFD. Due to increased fat oxidation (with decreased RQ) and increased energy expenditure (Keenan et al., 2006; Shen et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2008), rodents that received RS had significantly greater body fat reduction with continually elevated serum levels of the hormones PYY and GLP-1 rather than peaks of these hormones in serum only after food consumption to signal satiety (Keenan et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2008). In agreement with the rodent studies, the reduced IFD suggested an increased fat oxidation and increased energy expenditure rather than an augmented satiety or reduced food intake. Glucose appeared to increase gcy-8 gene expression which promotes fat storage. This effect is lost in the presence of the sir-2.1 deficient mutant or with the lack of daf-2/daf-16, which suggest that the additional glucose induced insulin resistance is dependent on daf-2 pathway and is suppressed by sir-2.1. The other genes do not seem to play much of a role, but the small increase in cpt-2 with glucose is reversed in sir-2.1 deficient mutant and the lack of both daf-2/daf-16. Since cpt-2 gene expression in the daf-16 deficient mutant did not change, the effect of glucose on cpt-2 was thought to be through daf-2 and that sir-2.1 inhibited that effect.

Extra glucose reduces C. elegans lifespan which may be independent of insulin-sensitivity and changes in body fat. As indicated by a surrogate marker of aging PPR, PWB sustained healthspan or lifespan. However, the PPR was not increased and was reduced with aging when an additional 2% glucose was added to all the strains tested except the daf-16/daf-2 deficient mutant. Like IFD, the effect of PWB on PPR was reversed in the daf-16/daf-2 deficient mutant with addition of glucose suggesting an independent mechanism which may involve a pathway outside of daf-2 or daf-2/daf-16 (Engelmann & Pujol, 2011; Zheng & Greenway, 2012), or that absence of the daf-2 promoted insulin sensitivity despite high levels of glucose. The PPR was dose-dependently elevated in all but the daf-2/daf-16 mutant indicating a dependency on daf-2 or daf-2/daf-16 as their absence eliminated the elevation of PPR. The sir-2.1 gene is related to the co-regulator/genes (Kyrylenko, Kyrylenko, Suuronen, & Salminen, 2003) and is partially responsible for aging in C. elegans (Houthoofd, Braeckman, Johnson, & Vanfleteren, 2003; Lakowski & Hekimi, 1998). Apparently, the effect of improved healthspan or lifespan was independent of sir-2.1 in the present study, which was more robust than in the daf-16 mutant. The daf-2/daf-16 mutant showed either no change or a minor change in PPR suggested the effect was insulin/IGF-1 like receptor pathway dependent, which was consistently absent in daf-16 mutant.

5. Conclusions

Our data demonstrated that PWB reduced IFD, decreased insulin-resistance, and improved healthspan or lifespan in the C. elegans model system which appeared to be primarily mediated via sir-2.1, daf-16, and daf-16/daf-2. C. elegans is an attractive in vivo animal model for initial studies of nutrition interventions prior to confirmation in higher animal species. The identified optimal functional food components may be incorporated in various ways into daily diet, because these are already known to have acceptability as food, and have been tested in clinical trials. A broader test of other sources of the functional components of PWB, such as, β-glucan, may provide more advantageous weight loss and obesity prevention. This could result in future improvements in public health.

Highlights.

Prowashonupana barley (PWB) is rich in β-glucan and dietary fermentable fiber.

PWB consumption reduced intestinal fat deposition in the C. elegans model organism.

PWB consumption improved healthspan in C. elegans.

PWB may help to reduce the world-wide obesity epidemic and the cost of health care.

Acknowledgments

The authors received a grant support from Louisiana Board of Regents Support Fund (LEQSF(2012-13-RD-B-09) and a matching grant from ConAgra Foods. The PWB used in this study was a gift donated by the ConAgra Mills® Inc. Supported in part (WDJ) by 1 U54 GM104940 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, which funds the Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Dr. Mark LeBlanc and Ms. Tammy Smith (Agricultural Chemistry Department, College of Agriculture, Louisiana State University) for their assistance on PWB sample preparation. The nematode strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (University of Minnesota, MN, USA), which is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). Louisiana State University Information Technology Service’s Wen-Chieh Fan improved the data mining in this project.

Abbreviations

- IFD

intestinal fat deposition

- PWB

Prowashonupana barley

- PPR

pharyngeal pumping rate

Footnotes

Chemical compounds studied in this article

Beta glucan (PubChem CID: 46173706)

Glucose (PubChem CID: 79025)

Vitamin B1 (Thiamin) (PubChem CID: 1130)

Vitamin B3 (Niacin) (PubChem CID: 938)

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Abate JP, Blackwell TK. Life is short, if sweet. Cell Metabolism. 2009;10(5):338–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JW, Akanji AO. Dietary fiber--an overview. Diabetes Care. 1991;14(12):1126–1131. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.12.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asare EK, Jaiswal S, Maley J, Baga M, Sammynaiken R, Rossnagel BG, Chibbar RN. Barley Grain Constituents, Starch Composition, and Structure Affect Starch in Vitro Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2011;59(9):4743–4754. doi: 10.1021/jf200054e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi K, Chang FY, Watts JL, Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Ruvkun G. Genome-wide RNAi analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans fat regulatory genes. Nature. 2003;421(6920):268–272. doi: 10.1038/nature01279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atherton HJ, Jones OA, Malik S, Miska EA, Griffin JL. A comparative metabolomic study of NHR-49 in Caenorhabditis elegans and PPAR-alpha in the mouse. FEBS Letters. 2008;582(12):1661–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behall KM, Scholfield DJ, Hallfrisch J. Comparison of hormone and glucose responses of overweight women to barley and oats. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2005;24(3):182–188. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2005.10719464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burks DJ, Font de MJ, Schubert M, Withers DJ, Myers MG, Towery HH, Altamuro SL, Flint CL, White MF. IRS-2 pathways integrate female reproduction and energy homeostasis. Nature. 2000;407(6802):377–382. doi: 10.1038/35030105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett C, Valentini S, Cabreiro F, Goss M, Somogyvari M, Piper MD, Hoddinott M, Sutphin GL, Leko V, McElwee JJ, Vazquez-Manrique RP, Orfila AM, Ackerman D, Au C, Vinti G, Riesen M, Howard K, Neri C, Bedalov A, Kaeberlein M, Soti C, Partridge L, Gems D. Absence of effects of Sir2 overexpression on lifespan in C. elegans and Drosophila. Nature. 2011;477(7365):482–485. doi: 10.1038/nature10296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekara A, Shahidi F. Determination of antioxidant activity in free and hydrolyzed fractions of millet grains and characterization of their phenolic profiles by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS n. Journal of Functional Foods. 2011;3(3):144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Chow DK, Glenn CF, Johnston JL, Goldberg IG, Wolkow CA. Sarcopenia in the Caenorhabditis elegans pharynx correlates with muscle contraction rate over lifespan. Experimental Gerontology. 2006;41(3):252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dongowski G, Huth M, Gebhardt E, Flamme W. Dietary fiber-rich barley products beneficially affect the intestinal tract of rats. Journal of Nutrition. 2002;132(12):3704–3714. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.12.3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman JB, Albinder B, Shroyer T, Kenyon C. The age-1 and daf-2 genes function in a common pathway to control the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1995;141(4):1399–1406. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.4.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann I, Pujol N. Innate Immunity in C. elegans. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2011;708:105–121. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8059-5_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feijo Delgado F, Cermak N, Hecht VC, Son S, Li Y, Knudsen SM, Olcum S, Higgins JM, Chen J, Grover WH, Manalis SR. Intracellular water exchange for measuring the dry mass, water mass and changes in chemical composition of iving cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e67590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley JW, Sandlin C, Holliday DL, Keenan MJ, Prinyawiwatkul W, Zheng J. Legumes reduced intestinal fat deposition in the Caenorhabditis elegans model system. Journal of Functional Foods. 2013;5(3):1487–1493. [Google Scholar]

- Frojdo S, Durand C, Molin L, Carey AL, El-Osta A, Kingwell BA, Febbraio MA, Solari F, Vidal H, Pirola L. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase as a novel functional target for the regulation of the insulin signaling pathway by SIRT1. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2011;335(2):166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gami MS, Wolkow CA. Studies of Caenorhabditis elegans DAF-2/insulin signaling reveal targets for pharmacological manipulation of lifespan. Aging Cell. 2006;5(1):31–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, Yin J, Zhang J, Ward RE, Martin RJ, Lefevre M, Cefalu WT, Ye J. Butyrate Improves Insulin Sensitivity and Increases Energy Expenditure in Mice. Diabetes. 2009;58(7):1509–1517. doi: 10.2337/db08-1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring JM. Resistant starch: safe intakes and legal status. Journal of AOAC International. 2004;87(3):733–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenway F, O’Neil CE, Stewart L, Rood J, Keenan M, Martin R. Fourteen weeks of treatment with Viscofiber increased fasting levels of glucagon-like peptide-1 and peptide-YY. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2007;10(4):720–724. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2007.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertweck M, Gobel C, Baumeister R. C. elegans SGK-1 is the critical component in the Akt/PKB kinase complex to control stress response and life span. Developmental Cell. 2004;6(4):577–588. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler HA, Huang H, Kier AB, Schroeder F. Glucose directly links to lipid metabolism through high affinity interaction with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(4):2246–2254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houthoofd K, Braeckman BP, Johnson TE, Vanfleteren JR. Life extension via dietary restriction is independent of the Ins/IGF-1 signalling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. Experimental Gerontology. 2003;38(9):947–954. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(03)00161-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt PR, Son TG, Wilson MA, Yu QS, Wood WH, Zhang Y, Becker KG, Greig NH, Mattson MP, Camandola S, Wolkow CA. Extension of lifespan in C. elegans by naphthoquinones that act through stress hormesis mechanisms. PLOS ONE. 2011;6(7):e21922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John J, Shahidi F. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) Journal of Functional Foods. 2010;2(3):196–209. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan MJ, Zhou J, McCutcheon KL, Raggio AM, Bateman HG, Todd E, Jones CK, Tulley RT, Melton S, Martin RJ, Hegsted M. Effects of resistant starch, a non-digestible fermentable fiber, on reducing body fat. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(9):1523–1534. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang R. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature. 1993;366(6454):461–464. doi: 10.1038/366461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga M, Take-uchi M, Tameishi T, Ohshima Y. Control of DAF-7 TGF-(alpha) expression and neuronal process development by a receptor tyrosine kinase KIN-8 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1999;126(23):5387–5398. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JM, Davidge JT, Lockyer JM, Staveley BE. Expression of Drosophila FOXO regulates growth and can phenocopy starvation. BMC Developmental Biology. 2003;3:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress AM, Hartzell MC, Peterson MR, Williams TV, Fagan NK. Status of U.S. military retirees and their spouses toward achieving Healthy People 2010 objectives. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2006;20(5):334–341. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-20.5.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrylenko S, Kyrylenko O, Suuronen T, Salminen A. Differential regulation of the Sir2 histone deacetylase gene family by inhibitors of class I and II histone deacetylases. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2003;60(9):1990–1997. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3090-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowski B, Hekimi S. The genetics of caloric restriction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(22):13091–13096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Murphy CT, Kenyon C. Glucose shortens the life span of C. elegans by downregulating DAF-16/FOXO activity and aquaporin gene expression. Cell Metabolism. 2009;10(5):379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifschitz CH, Grusak MA, Butte NF. Carbohydrate digestion in humans from a beta-glucan-enriched barley is reduced. Journal of Nutrition. 2002;132(9):2593–2596. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.9.2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhujith T, Amarowicz R, Shahidi F. Phenolic antioxidants in beans and their effects on inhibition of radical-induced DNA damage. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society. 2004;81(7):691–696. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau RA, Flores RA, Hicks KB. Composition of Functional Lipids in Hulled and Hulless Barley in Fractions Obtained by Scarification and in Barley Oil. Cereal Chemistry. 2007;84(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel DS, Garza-Garcia A, Nanji M, McElwee JJ, Ackerman D, Driscoll PC, Gems D. Clustering of genetically defined allele classes in the Caenorhabditis elegans DAF-2 insulin/IGF-1 receptor. Genetics. 2008;178(2):931–946. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.070813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendell M, Vanderhoof J, Venn M, Shehan MA, Arndt E, Rao CS, Gill G, Newman RK, Newman CW. Effect of a barley breakfast cereal on blood glucose and insulin response in normal and diabetic patients. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 2005;60(2):63–67. doi: 10.1007/s11130-005-5101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Keenan MJ, Martin RJ, Tulley RT, Raggio AM, McCutcheon KL, Zhou J. Dietary resistant starch increases hypothalamic POMC expression in rats. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17(1):40–45. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Ando H, Watanabe K, Takeda Y, Mitsunaga T. Physicochemical properties and structure of large, medium and small granule starches in fractions of normal barley endosperm. Carbohydrate Research. 2001;330(2):241–248. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)00292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissenbaum HA, Guarente L. Increased dosage of a sir-2 gene extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2001;410(6825):227–230. doi: 10.1038/35065638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissenbaum HA, Ruvkun G. An insulin-like signaling pathway affects both longevity and reproduction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1998;148(2):703–717. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.2.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoni SV, Brown GD. beta-Glucans and dectin-1. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1143:45–60. doi: 10.1196/annals.1443.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasanthan T, Bhatty RS. Enhancement of Resistant Starch (RS3) in Amylomaize, Barley, Field Pea and Lentil Starches. Starch - Stärke. 1998;50(Nr. 7. S.):286–291. [Google Scholar]

- Wadden TA, Frey DL. A multicenter evaluation of a proprietary weight loss program for the treatment of marked obesity: a five-year follow-up. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;22(2):203–212. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199709)22:2<203::aid-eat13>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wursch P, Pi-Sunyer FX. The role of viscous soluble fiber in the metabolic control of diabetes. A review with special emphasis on cereals rich in beta-glucan. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(11):1774–1780. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.11.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, Gao Z, Yin J, He Q. Hypoxia is a potential risk factor for chronic inflammation and adiponectin reduction in adipose tissue of ob/ob and dietary obese mice. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;293(4):E1118–E1128. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00435.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen K, Le TT, Bansal A, Narasimhan SD, Cheng JX, Tissenbaum HA. A comparative study of fat storage quantitation in nematode Caenorhabditis elegans using label and label-free methods. PLoS One. 2010;5(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You YJ, Kim J, Raizen DM, Avery L. Insulin, cGMP, and TGF-beta signals regulate food intake and quiescence in C. elegans: a model for satiety. Cell Metabolism. 2008;7(3):249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu YB, Dosanjh L, Lao L, Tan M, Shim BS, Luo Y. Cinnamomum cassia Bark in Two Herbal Formulas Increases Life Span in Caenorhabditis elegans via Insulin Signaling and Stress Response Pathways. PLOS ONE. 2010;5:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Barak N, Beck Y, Vasselli JR, King JF, King ML, We WQ, Fitzpatrick Z, Johnson WD, Finley JW, Martin RJ, Keenan MJ, Enright FM, Greenway FL. Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for obesity research. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Enright F, Keenan M, Finley J, Zhou J, Ye J, Greenway F, Senevirathne RN, Gissendanner CR, Manaois R, Prudente A, King JM, Martin R. Resistant starch, fermented resistant starch, and short-chain fatty acids reduce intestinal fat deposition in Caenorhabditis elegans. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010;58(8):4744–4748. doi: 10.1021/jf904583b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Greenway FL. Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for obesity research. International journal of obesity. 2012;36(2):186–194. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Hegsted M, McCutcheon KL, Keenan MJ, Xi X, Raggio AM, Martin RJ. Peptide YY and proglucagon mRNA expression patterns and regulation in the gut. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(4):683–689. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Martin RJ, Tulley RT, Raggio AM, McCutcheon KL, Shen L, Danna SC, Tripathy S, Hegested M, Keenan MJ. Dietary resistant starch up-regulates total GLP-1 and PYY in a sustained daylong manner through fermentation in rodents. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;295:E1160–E1166. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90637.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]