Abstract

Objectives

Lack of familiarity between teammates is linked to worsened safety in high-risk settings. The Emergency Department (ED) is a high-risk health care setting where unfamiliar teams are created by diversity in clinician shift schedules and flexibility in clinician movement across the department. We sought to characterize familiarity between clinician teammates in one urban teaching hospital Emergency Department (ED) over a 22-week study period.

Methods

We used a retrospective study design of shift-scheduling data to calculate the mean weekly hours of familiarity between teammates at the dyadic level, and the proportion of clinicians with a minimum of 2-hours, 5-hours, 10-hours, and 20-hours of familiarity at any given hour during the study period.

Results

Mean weekly hours of familiarity between ED clinician dyads was 2 hours (SD 1.5). At any given hour over the study period, the proportion of clinicians with a minimum of 2, 5, 10, or 20-hours of familiarity was 80%, 51%, 27%, and 0.8%, respectively.

Conclusions

In our study, few clinicians could be described as having a high level of familiarity with teammates. The limited familiarity between ED clinicians identified in this study may be a natural feature of ED care delivery in academic settings. We provide a template for measurement of ED team familiarity.

Keywords: Teamwork, Familiarity, Safety

INTRODUCTION

Teams are ubiquitous in healthcare, and positive teamwork is important to optimizing patient and provider safety. Teamwork refers to “behaviors of teammates that engender sharing of information and coordination of activities”.1 Leadership, adaptability, shared mental models, and mutual trust are several key components of teamwork.2 Poor teamwork can result from incompatible team design or incompatible team configuration, contributing to negative outcomes for patients and providers in the healthcare settings.3–6

The Emergency Department (ED) is a higher-risk setting because of the unpredictable patient volume and needs, and the associated wide range of skills required to manage individual patients.7–9 Risks may vary between EDs based on variability in the design of physical space and the care teams. A common feature of all EDs is that various combinations of physicians, nurses, technicians, and others gather quickly to form care teams.10 A subset of clinicians may be assigned to trauma or cardiac arrest care teams. Outside of these specific teams, the structure and size of other ED teams is often unspecified or haphazardly left to geographic assignments. In many cases, the formation of an ED may be comparable to a pick-up basketball game or flag-football game where individual teammates have a shared understanding of the goals of the game, they know their individual roles and responsibilities, but they may be unacquainted/unfamiliar with each other.

Familiarity is the amount of time that an individual spends exposed to his or her teammate(s). Familiarity is affected by turnover, absenteeism, and change in team configuration.11–16 Previous research links limited or no familiarity to deficits in teamwork behaviors such as communication, trust, and providing assistance to teammates.17,18 Research led by the National Aeronautic Space Administration found that errors in the aviation teams were more common in crews with limited familiarity.12 Errors during takeoff and landing are more common when familiarity between the pilot and co-pilot is limited or non-existent.19 A report on commercial aviation accidents between 1978 and 1990 found that more than 70% of crashes were linked to lack of familiarity between pilots and co-pilots.11 In studies concerning other types of teams, a similar pattern emerges with limited familiarity associated with inferior performance or poor teamwork.13,14,16,20,21

There has been limited research on the level of familiarity between ED clinicians. We hypothesized that familiarity between clinicians varies within and across shifts. This variability may create a threat to teamwork and patient safety. As a first step in research on familiarity and patient safety, we sought to characterize clinician teammate familiarity in a large urban academic ED.

METHODS

Study Design, Data Source, and Setting

We used a retrospective study design and reviewed administrative shift schedules at one urban academic ED to quantify familiarity. The ED, which receives >56,000 visits annually, is part of a tertiary care, academic medical center. It employs approximately 185 clinicians including physicians, nurses, and other clinical staff. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Study Setting and Population

Our study sample includes shift-scheduling data for attending physicians, emergency medicine resident physicians, nurses (RNs), patient care technicians (PCTs), and health unit coordinators (HUCs). The role of a PCT is to act as an assistant to RNs and physicians with the delivery of care to patients. The role of HUCs is to monitor throughput of patients and facilitate movement of patients from the ED to needed services based on patient need (e.g., the intensive care unit). We excluded clinicians with primary employment responsibilities outside of emergency medicine because of limited access to accurate and complete shift scheduling data for clinicians not based in the ED. This exclusion involves clinicians that perform off-service short rotations or short service periods in the ED during the study period.

Study Protocol

We collated shift-scheduling data for all clinician groups (i.e., nurses, physicians, technicians) scheduled for shifts from September 2010 to February 2011 (22 total weeks). We selected this time period based on the availability of shift scheduling data for all clinicians and labor and time involved in aggregating data from multiple diverse databases. We placed all schedule data into matrices to permit analysis of all possible dyadic pairings using Social Network Analysis (SNA) techniques.15 We used multiple software packages to analyze these data including Stata (College Station, TX: StataCorp LP), UCINET (Analytic Technologies, Lexington, KY), MATLAB (The MathWorks Inc.), and GraphPad Prism Version 4.0 (La Jolla, CA).

Measurements and Statistical Analysis

We used the 22-weeks of shift-scheduling data to calculate two measures of familiarity: 1) weekly mean familiarity; and 2) the proportion of clinicians with a minimum of 2, 5, 10, or 20-hours of familiarity at any given hour over the study period. We began by constructing total mean familiarity, defined as the mean number of hours that a particular type of clinician (e.g., attending physician) accumulated with another clinician (e.g., nurse) in the ED. For example, if an RN worked one 12-hour shift each week and an attending physician worked at the same time but only for 8-hours; the dyad would accumulate 176 total hours over a 22-week period. If another RN-attending physician dyad accumulated 125 total hours over the same period, and these four clinicians represented our study sample, the total mean familiarity for two RN-attending physician dyads would be (176+125/2 dyads = 150.5 hours). Based on a 40-hour workweek, the maximum amount of total mean familiarity that any two clinicians (dyad) can accumulate over a 22-week study period is 880 hours. We calculated weekly mean familiarity by dividing the total mean familiarity by the number of weeks in the study period. With our example above, weekly mean familiarity for RN-attending physician dyads would be (150.5/22 = 6.8 hours per week). The maximum weekly mean familiarity that any two clinicians can accumulate over the 22-week study period is 40-hours per week.

We calculated mean values and standard deviations to describe weekly mean familiarity by differing role-based dyads. We performed one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc comparison using GraphPad Prism Version 4.0 (La Jolla, CA) to evaluate differences in mean familiarity across clinician role categories (e.g., RN-RN dyads vs. RN-Attending MD dyads).

We then calculated a measure of familiarity based on the question: “At any given moment, what proportion of clinician dyads are familiar with each other?” We calculated this measure by stratifying shift data into one-hour time blocks. We identified all persons working in the ED for each and every one-hour segment over the 22-week study period. For each of these segments, we calculated the total number of possible clinician dyads as [((n × n)−n)/2]. If 19 clinicians were working during hour 200 into the study period, this would equal to 171 possible dyads [((19 × 19)−19)/2=171]. Next, we calculated the weekly mean familiarity over the entire study period for each possible clinician dyadic combination. Finally, we calculated the proportion of clinician dyads working in each one-hour increment that met the weekly mean familiarity threshold of 2-hours, 5-hours, 10-hours, or 20-hours. For example, we may determine that 19 clinicians were working at hour 200 into the study period and that 50% of the 171 possible dyads were “familiar” using the 2-hours of weekly mean familiarity as our threshold. We would arrive at this proportion by assigning a flag to each dyad that met a 2-hours/week threshold, and divide this number by all possible dyads for this hour (e.g., 86/171=50%).

RESULTS

Study Sample

We collected 22 total weeks of shift-scheduling data for 185 clinicians. We obtained the hours of scheduled shifts for 78 RNs, 23 PCTs, 7 HUCs, 30 attending physicians, and 47 resident physicians.

Familiarity

Weekly mean familiarity across all possible clinician dyads over 22-weeks was 2-hours (SD 1.5; Table 1). Weekly mean familiarity was lowest for resident-resident dyads (0.4-hours, SD 0.2) and highest for RN-HUC dyads (5.8-hours, SD 2.5).

Table 1.

Weekly mean familiarity between clinician dyads stratified by role

| Clinician Role | RN Mean(SD) |

PCT Mean(SD) |

HUC Mean(SD) |

Attending Mean(SD) |

Resident Mean(SD) |

All Mean(SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RN (n=78) | 4.2 (1.8) | |||||

| PCT (n=23) | 4.1 (2.3) | 3.0 (1.7) | ||||

| HUC (n=7) | 5.8 (0.8) | 5.3 (0.7) | 3.8 (1.0) | |||

| Attending (n=30) | 2.2 (1.1) | 2.1 (1.0) | 3.0 (1.5) | 0.8 (0.4) | ||

| Resident (n=47 | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.9 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.2) | |

| All (n=185) | 2.0 (1.5) | |||||

Global p-value for one-way ANOVA = p<0.0001 when comparing weekly mean familiarity of RN-RN dyads to RN-PCT, RN-HUC, RN-Attending, and so on.

Measures of familiarity may be affected by (skewed) if we include shift data from clinicians that worked a limited number of hours due to turnover or transfer to other departments during the study period. We evaluated the stability of this measure by excluding individuals from the dataset who worked less than 40 cumulative hours over the 22-week study period, considering that these employees were unlikely to have remained employed for the duration of the study period (sensitivity analysis). Using the 40-hour threshold, five clinicians were removed and we compared the summary familiarity measures with and without these clinicians. The analysis revealed no meaningful impact on total mean familiarity (53.2 vs. 54.6) and weekly mean familiarity (2.41 vs. 2.48).

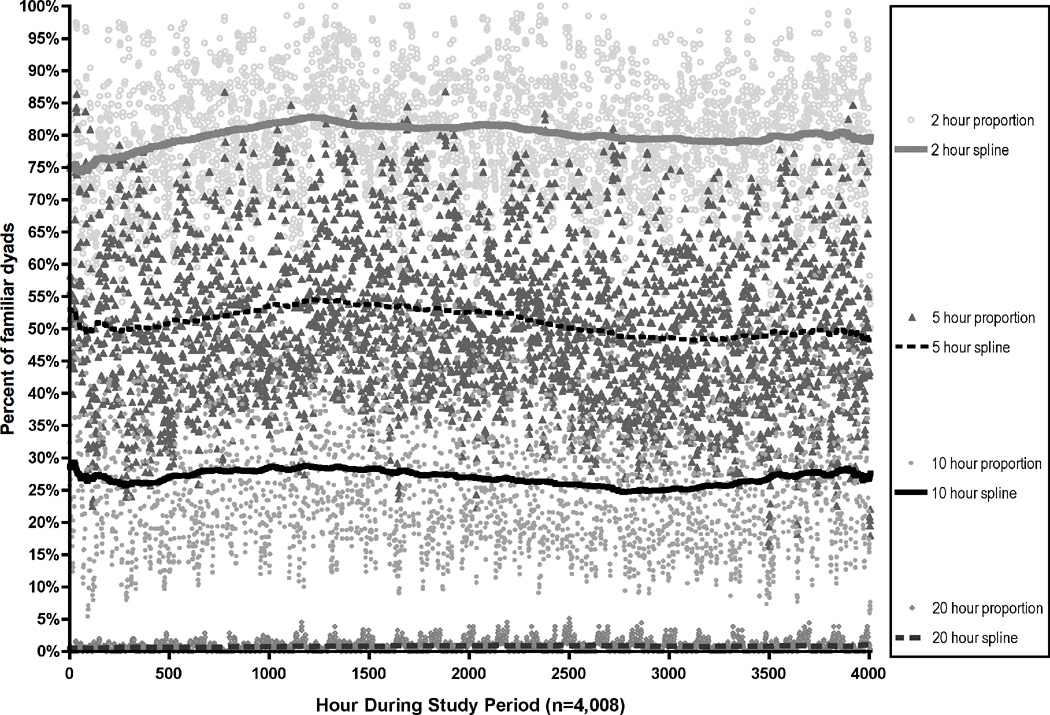

At any given hour of the study period, the mean proportion of clinician dyads that had at least 2-hours of familiarity with each other was 80.2% (SD=9.0, Min=48.6%, Max=100%; Figure 1). This proportion decreased with increases in the minimum threshold hours of familiarity between clinicians: 5-hours (mean=51.0%, SD=12.6, Min=16%, Max=86.8%); 10-hours (mean=26.8%, SD=10.8, Min=5.4%, Max=68.6%); and 20-hours (mean=0.8%, SD=0.8, Min=0.0%, Max=5.1%).

Figure 1.

For each hour of the study period, the proportion of clinicians familiar at four thresholds of familiarity (2-hours, 5-hours, 10-hours, and 20-hours).

This figure illustrates the proportion of unique dyads working in the ED at each hour of the study period that could be considered familiar according to four different thresholds. Each point is a proportion for that 1-hour increment. The lines were fit using a LOWESS procedure in GraphPad Prism Version 4 for Mac.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found limited familiarity between clinicians that work in the same academic ED. Health Unit Coordinators were found to have more mean weekly hours of familiarity with other clinician teammates than other clinicians while resident physician had the least. While resident physicians in this ED system rotate shifts between multiple sites, we were surprised that this led to their having very few hours of weekly familiarity with other clinicians. We were also surprised to learn that only 26% of clinician dyads had an average of 10-hours of familiarity per week over the study period.

We pointed out earlier that familiarity was associated with safety in many settings.11–14,16,20,21 Familiarity is also associated with efficiency. For example, in a study of 3-person teams, Harrison and colleagues showed that familiar teams completed assigned tasks faster than unfamiliar teams in a matter of a one or two meetings.13 In a study of 754 surgical procedures, familiarity between the attending surgeon and assisting surgeon was shown to impact total surgical time.20 The dyadic surgical team with more than 10 collaborative surgeries completed procedures was 34-minutes shorter than teams with no prior collaborations, and 13-minutes less than teams with 1–5 prior surgical collaborations.20 A separate study of air-traffic control teams (2–6 in size) determined that teammates with greater experience working together (mean=25 months, range 3–95 months) engaged in more positive teamwork behaviors than did unfamiliar teammates.16 Since this is the first study of familiarity among clinicians in an ED, we cannot compare our findings to those of other studies. However, familiarity is important in other high-risk fields, and we believe it will be important emergency medicine.

Questions emerging from our research include: How much familiarity is needed to ensure safe working conditions for patients and providers in the ED setting? How much familiarity is needed to achieve efficient outcomes? Answers may depend on numerous team and work factors including team size and design of the ED. We know that the design of some EDs creates a large, open layout with a single workstation where the demarcation of teams and grouping of teammates may not be clear and inhibit team formation.22 Lessons learned from implementation of teamwork in one large and open ED shows that implementation of positive teamwork principles is feasible, yet difficult to maintain due in part to the nature of ED shift work with different clinicians on different shift schedules and difficulty in maintaining a cohesive set of teammates.22 The ideal configuration and sizing of ED teams based on scheduling, familiarity, and optimization of care outcomes is unknown.

Current approaches to scheduling and staffing EDs may give little to no consideration to familiarity between clinicians. EDs may give precedence to achieving full staffing based on standards set by the hospital or department, or based on other criteria. Our findings indicate familiarity between clinicians in the ED is limited; given the data on familiarity and safety in other settings, we do not believe that familiarity should be ignored. Historical data from aviation would suggest that a large proportion of aviation accidents (>70% according to one historical report) could be linked to unfamiliar pilot/co-pilot teams. These data may have many passengers wanting to query the pilots of their plane prior to boarding with a simple question: “Is this your first day flying together?” We do not present data that links familiarity to ED outcomes, nor do we know of any such data published to date. However, the ED is a higher-risk setting than many other health care settings, making this topic a key health care and safety concern.

There is no single solution or “one-size fits all” answer to the problem of poor safety resulting from poorly performing teams. Familiarity between teammates is one factor (among many) that is largely a function of policies and procedures created by the organization. It is therefore an organizational factor, which according to experts, accounts for a large percentage of positive and negative outcomes of teams.23 Familiarity can be modified with multiple strategies. Greater familiarity may be achieved by assigning clinicians to dedicated teams (pods) that regularly work together in small rather than large groups. Greater familiarity may be realized if team-size is limited to 3–4 teammates – a number recommended in the team/groups literature as optimal for team performance improvement.24,25 Alternatively, clinicians may be rotated in and out of dedicated teams.

Valentine and Edmondson propose a version of pod creation in the ED setting that encourages competition between pods/teams.26 The insertion of competition appears to remove the threat of limited familiarity by creating cohesion amongst clinicians assigned to the pod. Analogous to a pick up sports game (e.g., basketball), the clinicians assigned to the pod share a common goal and come to the team with baseline knowledge of their role and assignment. Valentine and Edmondson refer to this approach as ‘team scaffolding.’26 Team scaffolding involves the setting of parameters for team size and structure, teammates are then assigned to a team or pod, and competition is stimulated to promote positive teamwork and high performance.

Another option is to incorporate familiarity into automated shift scheduling programs. Familiarity may be considered secondary to clinician preference. For example, after a clinician submits his/her shift requests, a scheduling program could be designed to use familiarity data and warn administrators of team configurations/partnerships where familiarity was at a level linked to higher rates of poor safety outcomes. Senior clinicians and administrators of the ED may also decide to use daily meetings of clinicians scheduled together or team training programs such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) TeamSTEPPS program.

LIMITATIONS

We are limited by data from one urban academic ED and the scheduling practices customary to this institution. Familiarity identified in this study sample may be characteristic of other academic institutions where familiarity between any two clinicians may be limited due in part to a large number of trainees. Familiarity is inherently higher in organizations or departments with fewer people. Non-academic, community-based or small facilities may employ fewer clinicians or adhere to scheduling practices that force a certain level of familiarity between select groups of clinicians. Even though the structure and scheduling practices of the study ED differs from that of other EDs, we believe that it is representative of many current EDs.

We do not account for clinician tenure or individual selection of scheduling preference. Both tenure and preference in schedule may play a role in the cumulative familiarity over time between any pair of clinicians. While we had access to historical shift records for the analysis, we did not have access to employment status. We used weekly mean familiarity based on the study period to determine the number of “familiar” clinician dyads at any given hour. Use of a period prior to start of our study may have resulted in a different weekly mean familiarity and affected the proportions of dyads deemed familiar across the different thresholds. Finally, we are limited to 22-weeks of archival shift data, which may not represent levels of familiarity calculated from shorter or longer study periods.

CONCLUSIONS

Our approach to measurement provides a template for inquiries into team structure, configuration, teamwork, and safety in the ED setting. We saw limited familiarity between ED clinicians in our study sample and posit that limited teammate familiarity is a potential threat to safety of patients and providers in EDs.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS.

Section 1: What is already known on this subject?

Evidence from aviation research and other high-risk settings

Suggests that lack of familiarity between teammates is associated with worse outcomes. Few studies have explored familiarity between doctors, nurses and ancillary staff in the Emergency Department.

Section 2: What do we know as a result of this study that we did not know before?

Analyzing one emergency department’s shift schedules using social analysis techniques, the authors found that on average, team members had only two hours of overlap per week.

Although outcome differences were not explored in this study, examination of work scheduling and patterns that impact familiarity among ED staff may be worthwhile.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources/Disclosures:

This work was supported by grants from the Emergency Medicine Patient Safety Foundation and Pittsburgh Emergency Medicine Foundation (www.pemf.net). Dr. Patterson is supported by a career-training award (Grant Number KL2 RR024154) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Dickinson TL, McIntyre RM. A Conceptual Framework for Teamwork Measurement. In: Brannick MT, Salas E, Prince C, editors. Team Performance Assessment and Measurement. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1997. pp. 19–43. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salas E, Sims DE, Burke CS. Is there a "Big Five" in teamwork? Small Group Research. 2005;36:555–599. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morey JC, Simon R, Jay GD, et al. Error reduction and performance improvement in the emergency department through formal teamwork training: evaluation results of the MedTeams project. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1553–1581. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazzocco K, Petitti DB, Fong KT, et al. Surgical team behaviors and patient outcomes. Am J Surg. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas EJ, Williams AL, Reichman EF, et al. Team training in neonatal resuscitation program for interns: teamwork and quality of resuscitations. Pediatrics. 2010 doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabol LI, Andersen ML, Osterbaard D, et al. Descriptions of verbal communication errors between staff. An analysis of 84 root cause analysis-reports from Danish hospitals. Qual Saf Health Care. 2011 doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.040238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chisholm CD, Dornfeld AM, Nelson DR, et al. Work interrupted: a comparison of workplace interruptions in emergency departments and primary care offices. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:6. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.115440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chisholm CD, Collison EK, Nelson DR, et al. Emergency department workplace interruptions: are emergency physicians "interrupt-driven" and "multi-tasking"? Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:5. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biros MH, Adams JG, Wears RL. Errors in emergency medicine: a call to action. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1173–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandez R, Kozlowski SW, Shapiro MJ, et al. Toward a definition of teamwork in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:1104–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NTSB. Washington, D.C.: National Transportation Safety Board; 1994. A Review of Flightcrew-Involved Major Accidents of U.S. Air Carriers, 1978 through 1990. Report No.: PB94-917001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foushee HC, Lauber JK, Baetge MM, et al. The Operational Significance of Exposure to Short-Haul Air Transport Operations. Moffett Field, California: National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 1986. Crew Factors in Flight Operations: III. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison DA, Mohammed S, McGrath JE, et al. Time matters in team performance: effects of member familiarity, entrainment, and task discontinuity on speed and quality. Personnel Psychology. 2003;56:633–669. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huckman RS, Staats BR, Upton DM. Team familiarity, role experience, and performance: Evidence from Indian software services. Manage Sci. 2009;55:85–100. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patterson PD, Arnold RM, Abebe K, et al. Variation in Emergency Medical Technician partner familiarity. Health Serv Res. 2011;46:1319–1331. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith-Jentsch KA, Kraiger K, Cannon-Bowers JA, et al. Do familiar teammates request and accept more backup? Transactive memory in air traffic control. Hum Factors. 2009;51:181–192. doi: 10.1177/0018720809335367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burt CD, Chmiel N, Hayes P. Implications of turnover and trust for safety attitudes and behavior in work teams. Saf Sci. 2009;47:1002–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burt CD, Stevenson RJ. The relationship between recruitment processes, familiarity, trust, perceived risk and safety. J Safety Res. 2009;40:365–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas MJ, Petrilli RM. Crew familiarity: operational experience, non-technical performance, and error management. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2006;77:41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu R, Carty MJ, Orgill DP, et al. The Teaming Curve: A longitudinal study of the influence of surgical team familiarity on operative time. Ann Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182864ffe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reagans R, Argote L, Brooks D. Individual experience and experience working together: Predicting learning rates from knowing who knows what and knowing how to work together. Manage Sci. 2005;51:869–881. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perry SJ, Wears RL, McDonald SS. Implementing Team Training in the Emergency Department: The Good, The Unexpected, and The Problematic. In: Salas E, Frush K, Baker DP, Battles JB, King HB, Wears RL, editors. Improving Patient Safety Through Teamwork and Team Training. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salisbury ML. Implementation. In: Salas E, Frush K, Baker DP, Battles JB, King HB, Wears RL, editors. Improving Patient Safety Through Teamwork and Team Training. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 177–187. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salas E, DiazGranados D, Klein C, et al. Does team training improve team performance? A meta analysis. Hum Factors. 2008;50:903–933. doi: 10.1518/001872008X375009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hackman JR, Vidmar N. Effects of size and task type on group performance and member reactions. Sociometry. 1970;33:17. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valentine MA, Edmondson AC. Team Scaffolds: How Minimal Team Structures Enable Role-Based Coordination. Harvard University Business School: Harvard University; 2013. [Google Scholar]