Abstract

Mutant superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) selectively associates with spinal cord mitochondria in rodent models of SOD1-mediated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. A portion of mutant SOD1 exists in a non-native/misfolded conformation that is selectively recognized by conformational antibodies. Misfolded SOD1 is common to all mutant SOD1 models, is uniquely found in areas affected by the disease and is considered to mediate toxicity. We report that misfolded SOD1 recognized by the antibody B8H10 is present in greater abundance in mitochondrial fractions of SOD1G93A rat spinal cords compared with oxidized SOD1, as recognized by the C4F6 antibody. Using a novel flow cytometric assay, we detect an age-dependent deposition of B8H10-reactive SOD1 on spinal cord mitochondria from both SOD1G93A rats and SOD1G37R mice. Mitochondrial damage, including increased mitochondrial volume, excess superoxide production and increased exposure of the toxic BH3 domain of Bcl-2, tracks positively with the presence of misfolded SOD1. Lastly, B8H10 reactive misfolded SOD1 is present in the lysates and mitochondrial fractions of lymphoblasts derived from ALS patients carrying SOD1 mutations, but not in controls. Together, these results highlight misfolded SOD1 as common to two ALS rodent animal models and familial ALS patient lymphoblasts with four different SOD1 mutations. Studies in the animal models point to a role for misfolded SOD1 in mitochondrial dysfunction in ALS pathogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a late onset neurodegenerative disease characterized by the loss of motor neurons (1). Twenty per cent of familial cases are due to mutations in superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) leading to the gain of an unknown toxicity. Mitochondria have long been considered a target of SOD1 toxicity due to reports of abnormal mitochondrial morphology in both patients (2) and animal models (3–5). Several aspects of mitochondrial function are reported as disturbed in ALS models including decreased electron transport activity (6,7), deregulated calcium handling (8,9), impaired protein import (10), increased exposure of the Bcl-2 BH3 domain (11) and diminished conductance of the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC1) (12). Whether such mitochondrial abnormalities actively contribute to the initiation or progression of ALS pathology, or rather are affected secondarily, remains unresolved.

SOD1 associates with mitochondria in an age-dependent and tissue-selective manner in multiple SOD1 rodent models and in ALS patient material harbouring SOD1 mutations (13–15). A portion of SOD1 does localize to the intermembrane space (IMS) (16), but forced localization of SOD1 to the IMS is inadequate to provoke sufficient mitochondrial damage so as to yield motor neuron loss or paralysis (17). While a proportion of the mutant SOD1 protein is tightly bound to the cytoplasmic face of the outer membrane of spinal cord mitochondria (15), whether such surface-bound mutant SOD1 contributes to disease pathogenesis remains an open question. To date, studies demonstrating mitochondrial dysfunction, whether in vivo or in vitro, report on the total mitochondrial population. However, only a portion of mitochondria have mutant SOD1 deposited on their outer membrane, leading to uncertainty as to which mitochondrial damage is linked to the association of mutant/misfolded SOD1.

A subset of SOD1 within spinal cord samples from ALS patients and SOD1 rodent models exists in an altered/non-normal conformation as demonstrated by a series of conformation restricted antibodies (15,18–23). Increasing evidence suggests that these alternative forms, collectively referred to as misfolded SOD1, underlie the inherent toxic nature of SOD1 mutations (20,24) as it is enriched in the motor neurons of both ALS rodent models and patient samples (19,20,22). We previously demonstrated that mitochondrial-associated SOD1 is misfolded (15) and localized within motor neurons in vivo (25). It remains undefined what type of mitochondrial damage is associated with this pool of mitochondrial-associated misfolded SOD1.

Using an antibody specifically detecting a misfolded form of SOD1, the clone B8H10, we provide evidence that B8H10-reactive misfolded SOD1 robustly associates with a subset of mitochondria isolated from SOD1 rodent models but not from wild-type controls. Moreover, this antibody identifies a subset of damaged spinal cord mitochondria in both SOD1G93A rats and LoxSOD1G37R mice. Mitochondrial defects appear prior to disease onset, clinical disease symptoms, gliosis and motor neuron loss. We also demonstrate for the first time that spinal cord mitochondria with surface-bound misfolded SOD1 have increased labelling for the toxic BH3 domain of Bcl-2, elevated production of mitochondrial superoxide and deregulated volume homeostasis. Lastly, we demonstrate B8H10-reactive misfolded SOD1 is present in lymphoblasts derived from ALS patients with SOD1 mutations and not in controls.

RESULTS

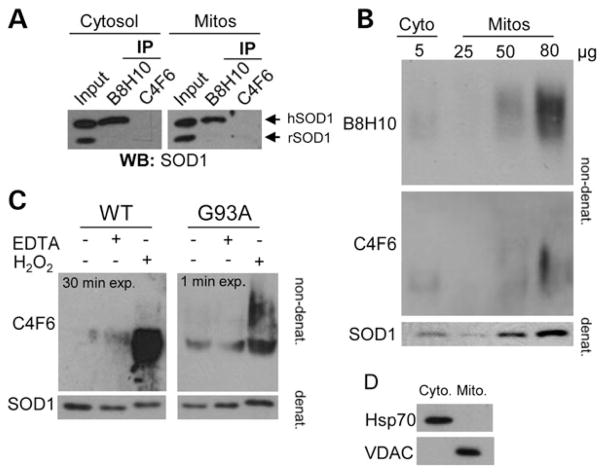

Differential detection of misfolded SOD1 on mitochondria by conformation-restricted antibodies

Recent progress in the field is marked by the development of a number of antibodies targeted to non-native conformations of SOD1, termed collectively as ‘misfolded SOD1’. One such antibody, the mouse monoclonal C4F6 antibody, has been shown to preferentially recognize H2O2-oxidized SOD1 (20), while the reactivity of other misfolded SOD1-specific monoclonal antibodies, such as A5C3, B8H10 and D3H5, to particular SOD1 subtypes, remains undefined. B8H10 has been used to effectively monitor misfolded SOD1 in a SOD1G93A mouse model following passive immunization with the D3H5 antibody, targeted to a different epitope of misfolded SOD1 (19). Importantly, decreased levels of B8H10-reactive misfolded SOD1 correlated positively with increased survival, increased motor neuron counts and attenuated gliosis in these D3H5-treated animals (19). Thus, we sought to determine if B8H10 and C4F6 were equally able to detect misfolded SOD1 in subcellular fractions enriched for spinal cord mitochondria isolated from symptomatic SOD1G93A rats. Interestingly, immunoprecipitation with B8H10, but not C4F6, robustly detected misfolded SOD1 in mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions from these animals (Fig. 1A). Since C4F6 has not been previously published in an immunoprecipitation assay, we considered that the antibody may not be well suited for this application and thus performed non-denaturing gel analysis for an independent evaluation of the mitochondrial association of misfolded SOD1 with these reagents. Specifically, we loaded a titration of purified mitochondria from the same animal on non-denaturing gels and blotted with B8H10 and C4F6. In this assay, densitometry determined that B8H10 immunoreactivity was detected 1.7 times more readily in mitochondrial fractions compared with C4F6 (Fig. 1B). Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were verified by immunoblotting with VDAC and Hsp70, respectively (Fig. 1D). To ensure that the C4F6 antibody was indeed able to recognize SOD1G93A and oxidized wild-type proteins as published, we treated recombinant mutant and wild-type SOD1 proteins with H2O2, as described previously (20). As a control, we also treated the recombinant proteins with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), another agent which has been previously published to provoke SOD1 misfolding, presumably via chelation of the zinc co-factor that is necessary for the structural integrity of SOD1 (19). Note, this method also likely chelates the copper which is required for dismutase activity, but is not considered essential for SOD1 toxicity (26). In agreement with previously published data, the C4F6 antibody robustly detects recombinant SOD1G93A and H2O2-treated wild-type proteins, albeit with much lower affinity to the latter. (Note the increased exposure time of immunoblots for recombinant SOD1WT compared with recombinant SOD1G93A protein.) C4F6 had only minor reactivity for untreated and EDTA-treated wild-type protein, confirming the published specificity of this antibody for SOD1G93A mutant and oxidized wild-type proteins (Fig. 1C). Collectively, these data suggest that these two antibodies recognize distinct SOD1 conformers with B8H10, but not C4F6, recognizing a conformer that demonstrates enhanced association with mitochondria.

Figure 1.

Preferential detection of B8H10 reactive misfolded SOD1 associated with mitochondria. The capacity of B8H10 and C4F6 antibodies to detect misfolded SOD1 was compared using mitochondrial and cytosolic protein fractions isolated from the spinal cord of symptomatic SOD1G93A rat or recombinant SOD1 using different conditions. (A) Immunoprecipitation of cytosolic or mitochondrial fractions from a symptomatic SOD1G93A rat with B8H10 or C4F6 misfolded SOD1-specific antibodies and blotted for SOD1. Input is 2 μg of each fraction. Upper and lower bands corresponds to human (hSOD1) and rat SOD1 (rSOD1), respectively. Experiment shown is representative of three independent trials. (B) Non-denaturing gel of cytosolic fraction (5 μg) or increasing amounts of the mitochondrial fraction (25, 50 and 80 μg) blotted with misfolded specific antibodies B8H10 and C4F6. Bottom: denaturing gel showing total amount of SOD1 present. Experiment shown is representative of three independent trials. (C) Non-denaturing gel of recombinant SOD1 proteins (6 μg) treated with EDTA or H2O2 to demonstrate specificity of the C4F6 antibody for SOD1G93A and oxidized SOD1WT proteins. Note the specificity of the C4F6 antibody for the SOD1G93A protein (1 min exposure) compared with the labelling of the SOD1WT protein (30 min exposure). Bottom: denaturing gel showing total SOD1present.(D) Immunoblotting of cellular fractions for VDAC andHsp70confirmed the identity of mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions, respectively.

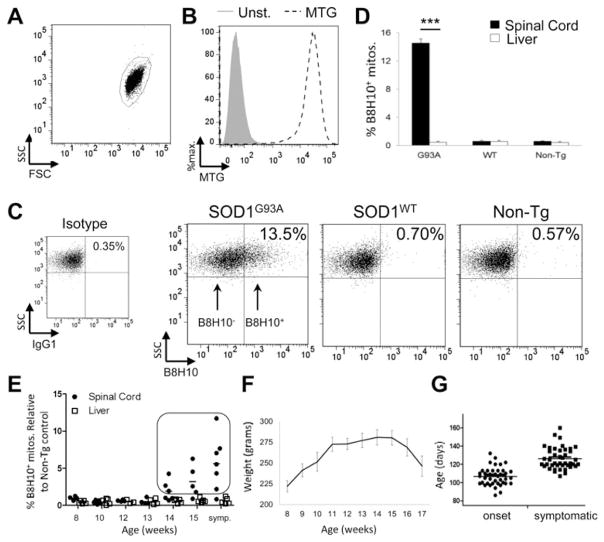

Immunodetection of mitochondrial-bound misfolded SOD1 by flow cytometry

Misfolded SOD1 associates with the mitochondrial surface of spinal cord mitochondria (12,15). We hypothesized that the presence of misfolded SOD1 may negatively affect key aspects of mitochondrial function. Given the prominence of a B8H10-reactive misfolded SOD1 species associated with SOD1G93A rat spinal cord mitochondria, we exploited this property to develop a quantitative flow cytometric assay whereby the function of mitochondria bearing misfolded SOD1 could be directly and selectively assessed using fluorescent immunodetection with B8H10 coupled with indicator dyes. In this assay, isolated mitochondria derived from the spinal cords of SOD1G93A rats are first selected/gated according to light scattering properties (Fig. 2A). Secondly, mitochondrial identity is confirmed via positive labelling with the mitochondria-specific, membrane potential independent fluorescent probe MitoTracker Green (MTG; Fig. 2B). These criteria demonstrate that 92.3±1.5% (n = 13) of collected events represent mitochondria. Of this mitochondrial population, selected based on MTG labelling, theB8H10 antibody selectively identifies a subset of spinal cord mitochondria with surface-bound misfolded SOD1 (B8H10+) in samples from symptomatic SOD1G93A rats but not age-matched transgenic SOD1WT rats which express comparable total levels of human SOD1WT protein or non-transgenic litter-mates (Fig. 2C). Analysis of multiple similarly-aged animals indicates that 14.5 ± 0.6% of SOD1G93A spinal cord mitochondria label positively for B8H10, while only 0.6 ± 0.1 and 0.5 ± 0.1% are detected in SOD1WT and non-transgenic rats, respectively (Fig. 2D). Importantly, preparations of liver mitochondria from the same SOD1G93A animals exhibited negligible levels of misfolded SOD1 labelling (0.5 ± 0.2%; P < 0.0001, n = 3 animals per genotype). Misfolded SOD1 was also minimal in liver mitochondria from SOD1WT (0.6 ± 0.2%) and non-transgenic rats (0.4 ± 0.1%; Fig. 2D). Collectively, these data establish a novel cytofluorometric assay to detect misfolded SOD1 and are in agreement with previous work documenting the association of misfolded SOD1 to be preferentially enriched on spinal cord mitochondria (12,15).

Figure 2.

Detection of mitochondrial-bound misfolded SOD1 by flow cytometry. Mitochondria were isolated from the spinal cord and liver of SOD1G93A, SOD1WT and non-transgenic rats and characterized by flow cytometry. (A) Isolated mitochondria are first gated by size (forward light scatter, FSC) and granularity (side scatter, SSC). (B) Mitochondria are then selected by staining with MTG (black, dashed) a mitochondrial-specific dye, compared with unstained control (grey, filled). (C) Mitochondria that label positive for B8H10 (B8H10+), compared with background labelling with isotype control (IgG1), are selected and mitochondrial function of the two subpopulations (B8H10+ versus B8H10−) can then be compared. (D) Quantification of B8H10+ mitochondria derived from the spinal cord (black) or liver (white) of symptomatic SOD1G93A rats (18.0 ± 1.1 weeks) and age-matched SOD1WT (17.6 ± 0.8 weeks) and non-transgenic rats (16.9 ± 0.9 weeks). Data are represented as the percentage of B8H10+ mitochondria (mean ± SEM), n = 3 animals per genotype and tissue, ***P < 0.0001. (E) By flow cytometry, the amount of mitochondria labelled with the B8H10 antibody increases over time in spinal cord (black circle), but not liver (white square), samples derived from SOD1G93A rats. Animals with greater than 1% of mitochondria labelling positive for B8H10 (boxed) were included in the functional analysis. n = 4–7 animals per time point. (F) Weight curve of SOD1G93A female rats were weighed and evaluated bi-weekly (n = 4–10 per time point). (G) Disease onset and symptomatic phase for all SOD1G93A rats used in this study. In our colony, the onset of disease, as defined by reaching peak body weight, corresponds to 15.2 weeks (107 ± 1.5 days, n = 43) and the appearance of symptoms, namely gait defects, occurred at 18.0 weeks (126 ± 1.8 days, n = 42). Based on these observations, the association of misfolded SOD1 with mitochondria begins prior to disease onset.

The deposition of misfolded SOD1 onto spinal cord mitochondria is age-dependent and occurs just prior to disease onset

Previous work using immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence demonstrated qualitatively that misfolded SOD1 is associated with mitochondria in late-staged/symptomatic ALS animals (12,15,25). In order to refine these observations, we used B8H10 detection via flow cytometry to quantitatively assess the amount and kinetics of misfolded SOD1 deposition on the surface of spinal cord mitochondria in the SOD1G93A rat model. We analyzed spinal cord and liver preparations from 36 animals spanning pre-symptomatic to symptomatic stages (8–18 weeks; Fig. 2E). In our cohort, misfolded SOD1 was appreciably detected on the surface of spinal cord mitochondria starting at 14 weeks, with a progressive age-dependent increase in the percentage of spinal cord mitochondria labelling for B8H10 over time (Fig. 2E). Misfolded SOD1 was not significantly detected on the surface of liver mitochondria from the same animals (Fig. 2E). Using a least-square regression model, age was determined to have a significant effect on the association of misfolded SOD1 with spinal cord mitochondria (P < 0.0001), but not liver mitochondria (P < 0.6227).

By monitoring our colony with the biweekly measurement of body weight and the observation of clinical/phenotypic disease behaviour, we determined that the deposition of misfolded SOD1 onto mitochondria occurs just prior to disease onset, as defined by peak body weight (Fig. 2F). This definition is objective and reliable, having been applied in other ALS animal models (27). At the time of disease onset, animals display a normal gait, normal hindlimb spread reflex and have full motility. In our SOD1G93A rat colony, onset was observed at 15.3 weeks (107 ± 1.5 days, n = 43), while the symptomatic stage, as determined by observation of gait defects, including limping or hopping, occurs at 18.0 weeks (126 ± 1.8 days, n = 42; Fig. 2G). These data demonstrate that misfolded SOD1 is associated with the surface of spinal cord mitochondria just prior to disease development in the SOD1G93A rat model. The timing of misfolded SOD1 association with mitochondria may suggest its involvement in disease onset.

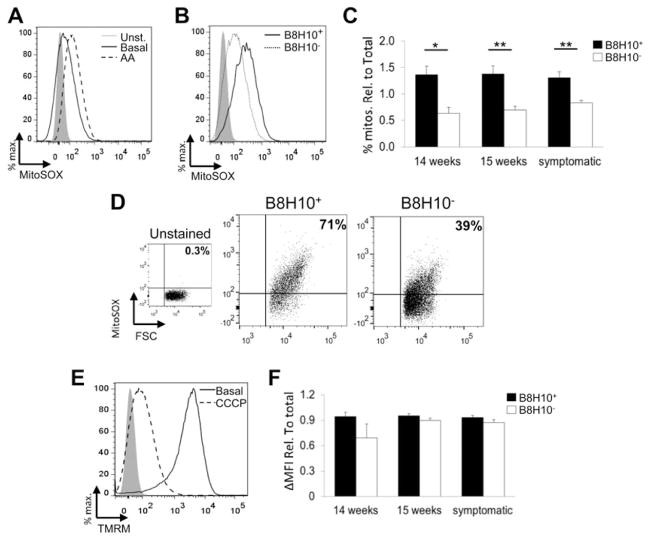

B8H10+ mitochondria have disrupted mitochondrial volume homeostasis

Animals displaying B8H10+ labelling of ≥1% of the total collected events, corresponding to a minimum of 1000 individual mitochondria, were included in subsequent functional analyses (Fig. 2E, boxed points). Specifically, subpopulations of mitochondria either coated with misfolded SOD1 (B8H10+) or not (B8H10−) were independently gated and compared for mitochondrial volume/size. Using flow cytometry, the intensity of light scattered at small angles from an incident laser beam, referred to as forward light scatter (FSC), is proportional to particle volume and thus can be used to estimate particle size (28,29). By this measurement, B8H10+ mitochondria demonstrate an increased volume/size compared with B8H10− mitochondria within the same preparation (Fig. 3A). Quantification of the geometric means of FSC revealed that the B8H10+ mitochondrial subpopulation was 1.5–2.0 times larger than B8H10− mitochondria. This observation was present at 14 weeks, the earliest time point where mitochondria labelled positive for B8H10-reactive misfolded SOD1 and persisted throughout the course of the disease (Fig. 3B; P < 0.0001). These data were confirmed with the mitochondrial-specific and potential-independent dye MTG where increased mean fluorescent intensity (ΔMFI) reflects an increased mitochondrial uptake of the dye which positively correlates with volume (30) (Fig. 3C). Starting at 14 weeks, B8H10+ mitochondria displayed ~3.0 × higher ΔMFI, a measure of the average fluorescent intensity of each mitochondrion, compared with B8H10− mitochondria (Fig. 3D; P < 0.0001). Overall, these results show that mitochondria bearing misfolded SOD1 have a greater mitochondrial volume compared with their counterparts not carrying such protein.

Figure 3.

Mitochondria with misfolded SOD1-associated have a greater mitochondrial volume. Mitochondria isolated from the spinal cords of SOD1G93A rats at different time points were characterized by flow cytometry. (A) Representative histogram of FSC of B8H10+ mitochondria (solid line) versus B8H10− mitochondria (dotted line) of a symptomatic SOD1G93A rat (B) Quantification of the geometric mean of FSC of B8H10+ mitochondria (black) and B8H10− mitochondria (white) relative to total population (mean ± SEM) at 14 and 15 weeks of age and symptomatic SOD1G93A rats. (C) Representative histogram of B8H10+ (solid line) and B8H10− (dotted line), mitochondria stained with MTG, compared with unstained control (grey, filled) of a symptomatic SOD1G93A rat. (D) ΔMFI of MTG staining of mitochondrial subpopulations relative to total population (mean ± SEM). ***P < 0.0001.

B8H10+ mitochondria produce excessive superoxide in the absence of depolarization

Our method of surface labelling isolated mitochondria does not include membrane permeabilization and thus preserves mitochondrial integrity. Thus, this methodology permits the use of membrane-permeable fluorescent indicator dyes to assess key features of mitochondrial function. Superoxide is a natural byproduct of normal mitochondrial respiration arising from complexes I and III of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, being released asymmetrically to both sides of the inner membrane (31). The superoxide released to the matrix side is essentially trapped due to the inherent impermeability of the inner membrane to superoxide and is efficiently detected by the fast-reacting membrane-permeable fluorescent indicator dye MitoSOX Red. MitoSOX Red becomes fluorescent following reaction with superoxide (31–33) as demonstrated by increased fluorescence following treatment with the complex III inhibitor Antimycin A (AA; Fig. 4A). To determine if mitochondrial superoxide levels are perturbed by the association of misfolded SOD1, we performed simultaneous B8H10 labelling and MitoSOX Red staining. A greater percentage of B8H10+ mitochondria labelled with MitoSOX Red compared with B8H10− mitochondria (Fig. 4B). Beginning at the earliest time point at which B8H10+ mitochondria were detected (14 weeks) and continuing to the symptomatic phase, an average of 1.9 times more B8H10+ mitochondria demonstrated elevated superoxide production, even when data were normalized for the increased size of B8H10+ mitochondria (Fig. 4C; P < 0.05 and P < 0.01). These data indicate that mitochondria coated with misfolded SOD1 produce excessive amounts of superoxide. Within the B8H10+ population, a positive correlation was noted between enlarged mitochondria (high FSC) and elevated superoxide levels (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Mitochondria with misfolded SOD1-associated exhibit an increased production of mitochondrial superoxide but retain a normal transmembrane potential. Mitochondria isolated from the spinal cord of SOD1G93A at different time points were characterized by flow cytometry for superoxide production and mitochondrial transmembrane potential. (A) Mitochondrial superoxide can be assayed with MitoSOX Red. Addition of the complex III inhibitor AA causes an increase in superoxide production (dashed line), compared with basal levels (solid line), and unstained control (grey, filled). (B) Representative histogram of mitochondrial superoxide production of B8H10+ (solid line) and B8H10−(dashed line) mitochondria from the spinal cord of a symptomatic SOD1G93A rat. (C) Quantification of the percentage of MitoSOX+ mitochondria in the B8H10+ (black) and B8H10− (white) populations, relative to MTG staining and the total mitochondrial population. (D) Representative dot plots demonstrating that the B8H10+ population has a higher percentage of larger mitochondria (as determined by FSC) that produce excessive mitochondrial superoxide (as measured by MitoSOX Red). (E) Histogram demonstrating that mitochondrial transmembrane potential can be assayed with TMRM. Under basal conditions, almost all mitochondria stain positive for TMRM (solid line), but transmembrane potential is dissipated with the addition of the protonophore CCCP (dashed lined). (F) Quantification of ΔMFI of TMRM staining of B8H10+ and B8H10− mitochondria relative to MTG staining and the total mitochondrial population. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ΔΨm) refers to the separation of charge across the inner mitochondrial membrane and is essential to drive ATP production via oxidative phosphorylation. Isolated spinal cord mitochondria were simultaneously labelled for misfolded SOD1 with the B8H10 antibody and stained with tetramethylrhodamine (TMRM). TMRM is a cationic dye that rapidly and reversibly equilibrates across the mitochondrial membrane in a voltage-dependent manner according to the Nernst equation (34). This can be demonstrated by treatment with the potent protonophore, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) which results in a significant dissipation of ΔΨm (Fig. 4E). While disturbances in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production are often linked to mitochondrial depolarization (35), we observed ΔΨm to be comparable between B8H10 subpopulations when data are normalized for size (Fig. 4F). These observations indicate that mitochondria carrying misfolded SOD1 have normal membrane potential. Conversely, superoxide production is increased suggesting that targeted mitochondrial damage tracks with the mitochondrial association of misfolded SOD1.

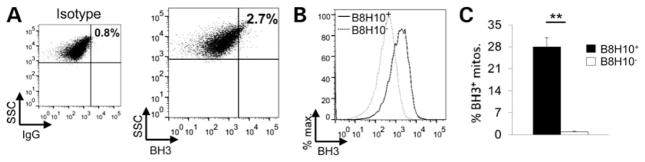

Increased exposure of the Bcl-2 BH3 domain in mitochondria coated with misfolded SOD1

It has recently been proposed that mutant SOD1 damages mitochondria by inducing a conformational change in the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 (11). Specifically, the binding of mutant SOD1 to Bcl-2 results in its conversion into a proapoptotic protein due to the exposure of the normally hidden BH3 domain. Using our flow cytometry assay, we performed simultaneous antibody labelling for misfolded SOD1 and the toxic BH3 domain of Bcl-2 on spinal cord mitochondria of SOD1G93A rats. Labelling for the BH3 domain of Bcl-2 was low in the total mitochondrial population as illustrated by a representative animal (Fig. 5A, 2.7±0.5%, n = 3). However, analysis of B8H10+ mitochondria demonstrated a 10-fold enrichment for the toxic BH3 domain of Bcl-2 (27.9 ± 3%) compared with B8H10− mitochondria which demonstrated negligible BH3 labelling (0.8 ± 0.3%; Fig. 5B and C; P < 0.01). Thus, spinal cord mitochondria coated with misfolded SOD1 are enriched for the Bcl-2 protein in a toxic conformation.

Figure 5.

Increased Bcl-2 BH3 domain exposure on mitochondria bearing misfolded SOD1. (A) Representative dot plot of spinal cord mitochondria from a symptomatic SOD1G93A rat labelled with a Bcl-2 antibody specific for the BH3 domain. The population labelling positive for the exposure of the BH3 domain (BH3+, 2.7 ± 0.5%, n = 3) was assessed in comparison with the isotype control (0.8 ± 0.01%) and represented as the mean ± SEM. (B) Mitochondria were also labelled with the B8H10 antibody. A representative histogram reveals that the B8H10+ (solid line) population has a higher amount of BH3+ mitochondria compared with the B8H10− (dashed line) population. (C) Quantification of BH3+ mitochondria from B8H10+ (black) and B8H10− (white) mitochondria (mean ± SEM, n = 3). **P < 0.01.

B8H10 labels misfolded SOD1 within motor neurons prior to gliosis and clinical disease

In an effort to determine the cellular origin of the mitochondria detected by our flow cytometric assay, we performed immunofluorescent labelling with B8H10 of lumbar spinal cord sections of a similar time course of SOD1G93A rats. Here, B8H10 extensively labels motor neurons identified by choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) staining starting at 14 weeks (Fig. 6A, top row), in agreement with previous work in mice (19). Moreover, B8H10 labelling was evident prior to astrogliosis and microglial activation, as marked by IbaI and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), respectively (Fig. 6B and C). Counts of lumbar motor neurons using cresyl violet staining (Fig. 6D) demonstrated a loss of 47% of motor neuron cell bodies at the symptomatic stage, corresponding to ~18.0 weeks (Fig. 6E; P = 0.0207) but not at 14 and 15 weeks, time points at which elevated B8H10 staining is observed. Taken together, B8H10 deposition on motor neuron mitochondria occurs prior to key pathological features of disease, including motor neuron loss and glial activation.

Figure 6.

Accumulation of misfolded SOD1 in motor neurons begins prior to gliosis and motor neuron loss. Immunohistochemical analysis of SOD1G93A and SOD1WT rat spinal cords at different time points. Transverse sections of the lumbar spinal cord were stained and analyzed accordingly. (A) Sections were stained with anti-B8H10 (green) and co-labelled with choline acetyltransferase (red) demonstrating the presence of misfolded SOD1 in motor neurons beginning at 14 weeks. (B) Sections were stained with anti-Iba-I (marker of macrophages/microglia) or (C) anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (astrocyte marker) to assess activation of microglia and astrocytes, respectively. (D) Representative image of spinal cord sections stained with Cresyl Violet. (E) Motor neurons in the anterior horn were counted and averaged per section (mean ± SEM, n = 3–5 per group). Scale bar = 100 μm. *P < 0.05.

Dysfunction of the B8H10+ mitochondrial subset in a second SOD1 model

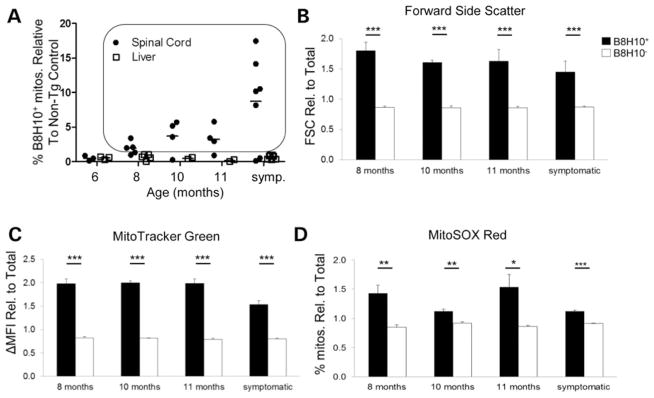

To demonstrate that the reported observations are common in ALS pathogenesis, and not confined to the SOD1G93A rat model, we also examined a time course of LoxSOD1G37R mice. These mice develop nearly identical muscle atrophy, motor neuron loss and gliosis but on an extended time span of ~12 months (36). Using these mice, we demonstrate a similar time-dependent deposition of misfolded SOD1, as detected by B8H10, on the surface of SOD1G37R spinal cord mitochondria (Fig. 7A). Moreover, B8H10+ labelling positively correlates with increased mitochondrial volume (Fig. 7B and C; P < 0.0001) and excess superoxide production (Fig. 7D) to similar degrees as observed in SOD1G93A rats (FSC: 1.8-fold, MTG ΔMFI: 2.2-fold and % of MitoSOX Red+ mitochondria: 1.5-fold), indicating that these are common features of mitochondrial damage in mutant SOD1 ALS models. Importantly, in Lox-SOD1G37R mice, these changes occurred as early as 8 months, a point at which animals are clearly pre-symptomatic and lack any overt pathogenic changes (36). Due to mouse sample limitations, we were unable to assess mitochondrial polarization status. B8H10-reactive misfolded SOD1, and its ability to identify dysfunctional mitochondria, are a common feature of two ALS rodent models.

Figure 7.

Mitochondrial-associated misfolded SOD1 tracks with mitochondrial damage in the SOD1G37R mouse model. (A) The number of spinal cord (black circle), but not liver (white square), mitochondria that label positive for B8H10 increases with age. Each dot represents an individual mouse. Animals with greater than 1% of mitochondria labelling positive for B8H10 (within black box) were included in the functional analysis. (B) Quantification of the geometric mean of FSC of B8H10+ mitochondria (black) and B8H10− mitochondria (white) relative to the total population. (C) Quantification of ΔMFI of MTG of B8H10+ mitochondria and B8H10− mitochondria relative to the total population. (D) Quantification of the percentage of MitoSOX+ mitochondria in each mitochondrial subpopulation relative to the total population. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001.

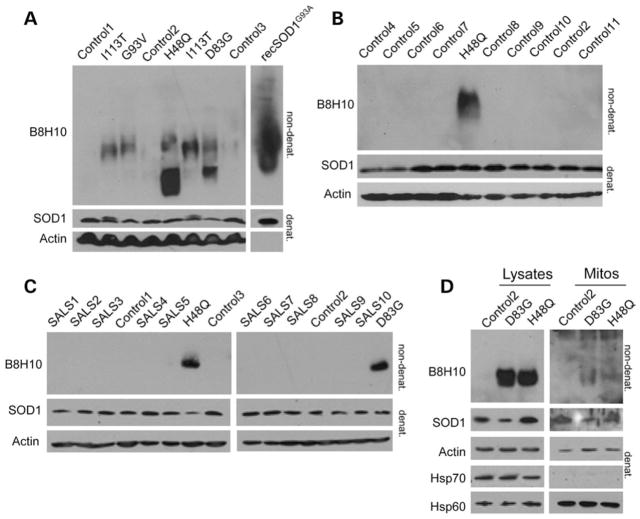

B8H10 immunoreactivity in ALS patient cells

Transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from five ALS patients expressing four different SOD1 mutations (H48Q, D83G, G93V and I113T) were analyzed on non-denaturing gels for the presence of misfolded SOD1. B8H10 positively identified misfolded SOD1 to differing extents in five patient cell lines, while no signal was detected in cells derived from three healthy controls (Fig. 8A). Eight additional controls were screened to verify that the B8H10 signal was in fact due to misfolded mutant SOD1, and indeed, no B8H10 reactivity was detected (Fig. 8B). We also analyzed 10 sporadic ALS (sALS) patient cells but, if B8H10-reactive misfolded SOD1 is present in these lines, it was below the level of detection (Fig. 8C). To assess if B8H10-reactive misfolded SOD1 was associated with mitochondria in this cell type, mitochondria were magnetically isolated and immunoblotted for the presence of misfolded SOD1 with B8H10. Magnetic bead isolation avoids any potential artefact from co-sedimenting aggregates. Indeed, mitochondria from patients with SOD1 mutations labelled modestly for B8H10, while mitochondria isolated from a healthy individual did not (Fig. 8D). However, the amount of misfolded SOD1 on mitochondria appeared to be insufficient to induce any appreciable elevation in superoxide production when measured on the whole population (data not shown). Regardless, these data highlight that the association of misfolded SOD1 with mitochondria is central to ALS as it is found in both rodent models and human patient material.

Figure 8.

Misfolded SOD1 detection in ALS patient cells. Cell lysates were prepared from lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from healthy controls, non-ALS disease controls, sporadic ALS patients or familial ALS patients identified with SOD1 mutations and screened for B8H10-reactive SOD1. (A) Non-denaturing gel of lysates from healthy controls (controls 1–3) and ALS patients identified with SOD1 mutations (H48Q, D83G, G93V and I113T) were tested for reactivity with the B8H10 antibody targeted against misfolded SOD1. Recombinant SOD1G93A protein (100 ng) served as a positive control to verify the detection of misfolded SOD1. Bottom: denaturing gel blotted for total SOD1 and Actin served as loading controls. (B) Healthy controls (2) and non-ALS diseased controls (one individual with insomnia, two individuals with obsessive compulsive disorder and four individuals with sleeping disorders) were screened for B8H10-reactive misfolded SOD1. Bottom: denaturing gel blotted for total SOD1 and Actin served as loading controls. (C) Sporadic ALS patients (SALS 1–10) were screened for B8H10-reactive misfolded SOD1. Mutant SOD1 patients (H48Q and D83G) and three controls are included as positive and negative controls, respectively, for the B8H10 antibody. Bottom: denaturing gel blotted for total SOD1 and Actin served as a loading control. (D) Isolated mitochondria from one healthy control and two ALS patients carrying SOD1 mutations (D83G and H48Q) were probed for B8H10 reactivity on non-denaturing gels. Bottom: denaturing gel blotted for total SOD1, Hsp70 and Hsp60 which serve as controls for the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial fractions, respectively. Actin serves as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

Our ex vivo analysis of SOD1G93A rat spinal cord mitochondria with surface bound misfolded SOD1 (B8H10+) reveal several aspects of mitochondrial dysfunction that correlates positively with disease. Using a novel quantitative approach, we report that B8H10+ mitochondria exhibit increased volume compared with their B8H10− counterparts, have elevated superoxide levels and enhanced exposure of the toxic BH3 domain of Bcl-2. Increased mitochondrial volume could arise from either mitochondrial swelling or increased mitochondrial fusion. Our findings that mutant/misfolded SOD1 associates with increased mitochondria volume are in line with histological examination of the spinal cords of ALS patients (37) and mutant SOD1 transgenic animals (3,25,38,39), where swollen and aggregated mitochondria have been observed. Similarly, neuron-like cell lines and primary motor neurons also exhibit swollen mitochondria following mutant SOD1 expression (8,40,41). In our previous studies, we found significant morphological changes of motor neuron mitochondria in both axons and cell bodies (25). The significance of this increased volume/size is unclear but could be due to defects in ionic homeostasis causing mitochondrial swelling, altered fission/fusion dynamics causing larger mitochondria or defective autophagy, resulting in the inability to clear large or swollen mitochondria.

In support of ionic homeostasis dysfunction, VDAC1 conductance is reportedly impaired by mutant SOD1, effectively disrupting normal ionic homeostasis (12). However, it has also been reported that mutant SOD1 is associated with spinal cord mitochondria even in the absence of VDAC1 (10). Also, given that the genetic deletion of VDAC1 in the LoxSOD1G37R background yielded an accelerated disease phenotype, it is unclear how VDAC1 is a required mediator of misfolded SOD1 toxicity (12). The model proposed by Israelson et al. (12) predicts that altered VDAC conductance will decrease metabolites entering the mitochondria, resulting in decreased ATP synthesis and a depolarization of mitochondrial transmembrane potential. However, we find mitochondrial transmembrane potential of isolated mitochondria to be unaffected by the presence of misfolded SOD1 (Fig. 4) and ATP synthesis is reported to be unchanged (10). While there is clearly some ambiguity about the importance of VDAC in disease pathogenesis, it is noteworthy that in liver mitochondria, increased mitochondrial superoxide can be triggered by VDAC closure (42). Moreover, VDAC has been shown to regulate the release of mitochondrial superoxide to the cytosol in certain cases (43,44). Additional experiments will be needed to resolve this issue.

A previous report using human neuroblastoma cells overexpressing various SOD1 mutations documented increased superoxide levels but the mechanisms involved were not identified (45). From our analysis of mitochondria isolated from mutant SOD1 animal models, we find that misfolded SOD1 bearing mitochondria specifically produce very high levels of superoxide weeks before disease onset (Figs 4 and 7). Mitochondria are the principle cellular generators of ROS and mitochondria are equipped with a mitochondrial SOD (SOD2) to detoxify superoxide generated by mitochondria. While SOD2 can attenuate toxicity in cell culture (45), the role of SOD2 in mutant SOD1 mouse models is less clear (46). However, the mitochondrial redox system has been strongly implicated in ALS. In cell culture, SOD1 mutant proteins were found to associate with mitochondria and cause a shift to an oxidizing redox environment (47). Recently, mutant SOD1 was shown to activate p66Shc, a protein involved in controlling mitochondrial redox in neuronal-like cells (48).

We also examined whether the presence of misfolded SOD1 on mitochondria correlated with the conversion of Bcl-2 to a toxic conformation. In our experiments, we demonstrate for the first time that a robust proportion of mitochondria bearing misfolded SOD1 exhibit positive labelling for the BH3 domain of Bcl-2. Although this is not a direct test of an interaction between Bcl-2 and misfolded SOD1, it is compatible with the view that the exposure of Bcl-2’s BH3 domain is deleterious to mitochondrial function (11), as we demonstrate that B8H10+ mitochondria are functionally impaired compared with their B8H10− counterparts. Interestingly, in vitro experiments have shown that glutathione interacts with Bcl-2 in the BH3 groove, as BH3 mimetics disrupt this interaction (49). BH3 mimetics also disrupt mitochondrial glutathione levels and decrease the ability of isolated mitochondria to import glutathione (49). That we find both increased levels of the toxic BH3-exposed Bcl-2 conformer and increased superoxide suggests that misfolded SOD1 may cause an alteration in mitochondrial redox causing increased levels of superoxide in vivo.

For the first time, we show in vivo that misfolded SOD1 association with mitochondria correlates positively with increased mitochondrial volume, superoxide production and the presence of a toxic conformer of Bcl-2. Although our methods are currently unable to differentiate if misfolded SOD1 directly causes the damage or is recruited to mitochondria following damage, both scenarios are possible, and are currently under evaluation in our lab. For misfolded SOD1 as the cause, overexpression of mutant SOD1 in cell culture has been shown to associate with mitochondria and cause increased ROS production (49).

We place the deposition of misfolded B8H10+ SOD1 onto the mitochondrial outer membrane as early as 14 weeks in the SOD1G93A rat and 8 months in SOD1G37R mice, which is prior to disease onset. Our analysis of pathological hallmarks in the rat model shows that misfolded SOD1 protein is robustly detected within the motor neurons of the ventral spinal cord at time points prior to gliosis and significant motor neuron loss. Levels of mitochondrially associated misfolded SOD1 peak at the symptomatic stage, despite the loss of motor neurons, and decreased B8H10 immunoreactivity in spinal cord sections. This is consistent with a previous report in SOD1G93A mice where misfolded SOD1, as detected by the misfolded SOD1-specific antibody D3H5, was increased in the spinal cord despite motor neuron loss (19). This apparent paradox could be explained if the levels of misfolded SOD1 present in each individual cell increases over time, and this subsequently provokes misfolded SOD1 enrichment at the mitochondria. In support of this, it has been reported that that the level of human mutant SOD1 in the spinal cords of SOD1G93A rats increases in an age-dependent manner, peaking at end-stage (50). Knowledge that mitochondrial damage occurs pre-symptomatically may be instrumental in deciding when misfolded SOD1 and/or mitochondrial-targeted therapeutics will be most efficacious. That diminution of B8H10-reactive SOD1 in the spinal cords of SOD1G93A mice following passive immunization with a misfolded SOD1 antibody, clone D3H5, correlated positively with survival, suggests that this form of misfolded SOD1 is intimately linked to the toxicity of mutant SOD1 (19). We theorize that therapies aimed at decreasing B8H10-reactive misfolded could prevent or decrease its association with spinal cord mitochondria and subsequent mitochondrial damage.

Accumulating evidence suggests that misfolded SOD1 mediates ALS pathogenesis (19,20). However, the field fails to completely understand which biological pathways are disrupted by the presence of these non-native SOD1 proteins. Our initial experiments guided us to select B8H10 for the mitochondrial function experiments, but also suggested that more than one form of misfolded SOD1 exists. This concept is supported by recent data from others (24,51). Here, using the SOD1G93A rat and SOD1G37R mouse model, we find that B8H10-reactive misfolded SOD1 is associated with spinal cord mitochondria. In contrast, little C4F6-reactive SOD1 was detected in these same samples. Within our cohort, one symptomatic rat and two symptomatic mice exhibited mitochondria-associated B8H10-reactive misfolded SOD1 that was below our threshold. These outliers raise the question: if mitochondrial damage is central to disease, how can these animals which lack appreciable levels of misfolded SOD1 associated with the mitochondria exhibit symptoms? We propose two possible hypotheses. First, mitochondrial damage may still be central to disease, if other conformers of misfolded SOD1 are also associated with mitochondria. Previous work has shown that at least three other misfolded SOD1 antibodies detect SOD1 at the mitochondria: SEDI (18), DSE2 (15) and A5C3 (25). Alternately, there may be non-mitochondrial mechanisms of misfolded SOD1 toxicity. It has been demonstrated that the C4F6 antibody recognizes recombinant wild-type SOD1 oxidized by H2O2 (20). In this same study, the addition of oxidized wild-type SOD1 or mutant SOD1 altered the axonal transport in a squid axoplasm model. Perfusion of the C4F6 antibody in this system corrected the axonal transport defect induced by oxidized/misfolded SOD1. Given this evidence, we feel it is likely that distinct SOD1 conformers may differentially influence cellular mechanisms. Specifically, B8H10-misfolded SOD1 links to mitochondrial-based modes of pathogenesis, while we propose that C4F6-misfolded SOD1 impacts axonal transport but not mitochondria.

Lastly, we detected B8H10-reactive misfolded SOD1 in patient-derived lymphoblasts, a cell type generally considered to be unaffected by disease. While the rationale of why misfolded SOD1 is detected in these cells is not readily apparent, it is consistent with work by others using the recently described MS785 antibody which demonstrates an altered SOD1 conformer (52) as well as another study indicating the presence of an over-oxidized SOD1 conformer (53) in these same cells. Combined with our data from ALS animal models, B8H10-reactive SOD1 is common to six different SOD1 mutations, emphasizing that this conformation of misfolded SOD1 may be especially relevant for SOD1-mediated toxicity. However, the amount of misfolded SOD1 detected on mitochondria from patient lymphoblasts was insufficient to induce any appreciable elevation in superoxide production when measured on the whole population raising the possibility that mitochondrial dysfunction and toxicity may be dependent on intrinsic cell type characteristics and/or the level of mitochondrial-associated misfolded SOD1. We speculate that long lived cells, such as motor neurons, may be predisposed to damage resulting from the association of misfolded SOD1 onto mitochondria, whereas rapidly turned over cells (e.g. cells in the liver) may not acquire sufficient levels of SOD1 association or are unaffected by such mitochondrial association (e.g. lymphoblast cells). Our data suggest that this is plausible, given that the number of mitochondria carrying B8H10-reactive SOD1 increased with age in the animal models. As a final thought, while lymphoblasts may not be the appropriate cell type for mechanistic studies probing mitochondrial dysfunction in relation to misfolded SOD1, these cells are easily accessible and thus may offer a potentially useful way by which to monitor misfolded SOD1 levels, disease progression, efficacy of therapeutics and/or a priori selection of patients for particular clinical trials.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

SOD1G93A and SOD1WT transgenic rats and LoxSOD1G37R mice have been described previously (36,50,54). In some experiments, non-transgenic littermates were used. SOD1G93A rats were monitored with biweekly weight measurements and observation. In order to limit the impact of genetic drift inherent to transgenic lines, all SOD1G93A rats used to breed the colony were maintained until end-stage in order to validate disease course and thus ensure that only progeny of animals which developed symptoms ‘on-time’ were selected for subsequent breeding. Rats presenting with forelimb paralysis were eliminated from the colony and the study. Animals of both sexes were used. LoxG37R mice were also similarly followed and monitored for disease. Animals were treated in strict adherence with approved protocols from the CRCHUM Institutional Committee for the Protection of Animals and the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC).

Antibodies

For western blot, human-specific rabbit anti-SOD1 (Cell Signalling), rabbit anti-Cu/Zn SOD (Stressgen), mouse anti-VDAC1 (Calbiochem), mouse anti-Hsp70 (Chemicon) and mouse anti-Hsp60 (BD Biosciences) were used. For immunoprecipitation and native gels, misfolded SOD1 monoclonal antibody B8H10 (Medimabs and JP Julien lab), and misfolded SOD1 monoclonal antibody C4F6 (Medimabs) were employed. For flow cytometry, misfolded SOD1 monoclonal antibody B8H10 (Medimabs), mouse anti-IgG1 (BD Biosciences), rabbit anti-BH3 Bcl-2 antibody (Abgent) and rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were purchased. For immunofluorescence, rabbit anti-IbaI (Wako) and rabbit anti-GFAP (Dako) were used.

Flow cytometry of isolated mitochondria

Spinal cord and liver mitochondria were isolated from mice and rats exactly as described previously (15). Mitochondria (25 μg) were re-suspended in M Buffer (220 mM sucrose, 68 mM mannitol, 10 mM KCl, 5 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM MgCl2, 500 μM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid, 5 mM succinate, 2 μM rotenone, 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, pH 7.2, 0.1% fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin [BSA]). For labelling with antibodies, mitochondria were first blocked with M buffer supplemented with 10% fatty acid-free BSA for 15 min at 4°C. Mitochondria were then incubated with primary antibody for 30 min at 4°C, washed once with M buffer and then incubated with allyphycocyanin-conjugated fluorescent secondary antibody for 30 min at 4°C. MTG (100 nM; Invitrogen) was used to confirm mitochondrial identity. TMRM Methyl Ester (100 nM; Invitrogen) was used to assess mitochondria membrane potential (ΔΨm) and MitoSOX Red (MitoSOX, 5 μM; Invitrogen) to quantify mitochondrial superoxide. The protonophore CCCP (100 μM; Sigma) was used as a control for ΔΨm measurements, and the complex III inhibitor, AA (100 μM; Sigma) was used as a control for mitochondrial superoxide production. 100 000 events were acquired on a LSR II flow cytometry (BD Biosciences). Mitochondria were gated according to light scatter, after doublets were excluded, then MTG staining and labelling with B8H10 were assessed. All flow cytometry data were analyzed with FlowJo (Treestar, Ashland, OR, USA). Dyes and anti-bodies selected exhibited distinct spectral properties with minimal to no overlap. Where necessary, compensation was applied according to single-colour control samples. CCCP- and AA-treated samples were included in every experiment to confirm that the dyes functioned as expected. An isotype control sample was also included in every experiment to ensure the specificity of the B8H10 antibody.

Immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting and native gel analysis

Isolated mitochondria were solubilized and immunoprecipitated as described previously (15). Samples for native gel analysis were prepared with 2× loading buffer (Invitrogen), separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 12% Tris-Glycine Gels (Invitrogen) in running buffer (Invitrogen) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (BioRad). Densitometry was performed with ImageJ. For denaturing gels, nitrocellulose was used.

Immunofluorescence

Animals were transcardially perfused with 4% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde (FD NeuroTechnologies). Tissues were subsequently dissected, post-fixed for 2 h, cryoprotected, and then embedded in OCT (TissueTek). 30 μm floating spinal cord sections were cut from the lumbar region (L4–L6; corresponding to the lumbar enlargement) to make sure that all animals are adequately compared and labelled with B8H10, Iba-I or GFAP, as previously described (19) or cresyl violet (55). Immunofluorescent images were captured by confocal microscope (Leica SP5; 20x objective, 1.7 NA) and processed with Leica LAS AF software and/or PhotoshopCS4 (Adobe). Images of cresyl violet stained sections were captured on a Leica DM600B light microscope. Motor neurons, determined by size and location in ventral horn from 20 lumbar sections per animal were counted, spaced at 90 μm intervals. Three to five animals per group were evaluated.

Patient cells

Lymphocytes were isolated from peripheral blood samples using standard protocols and then immortalized with Epstein–Barr virus (56). In all experiments, controls (four healthy donors, seven non-neurodegenerative donors; insomnia, sleeping disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder), 10 sporadic ALS and mutant SOD1-ALS (H48Q, D83G, G93V and two I113T) cells were thawed at the same time and cultured in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 300 IU/ml penicillin, 300 μg/ml streptomycin and 0.5% fungi-zone. Isolation of mitochondria from lymphoblasts was done using the Mitochondrial Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Protocols were approved by the ethics committee on human experimentation of the Center Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal. All patients gave written informed consent prior to the collection of patient information and blood.

Statistics

Student’s t-test was used to determine that B8H10 labelling of spinal cord mitochondria is significantly different from B8H10 labelling of liver mitochondria from SOD1G93A rats. A least-square regression model was used to determine that time (age of animal) had an effect on misfolded SOD1 association with spinal cord, but not liver, mitochondria in the SOD1G93A rat model. Analysis of variance was used to evaluate differences in B8H10+ and B8H10− mitochondria subpopulations in rat and mouse models and motor neuron counts in 8 weeks and symptomatic rats. Student’s t-test was also used to analyze differences in B8H10+ and B8H10− mitochondrial subpopulation for BH3 labelling (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.0001).

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Lobsiger, S. Boillée, P.A. Dion, H. McBride and J. St-Pierre for valuable discussions; L. Hayward for baculoviruses and A. Prat for access to the flow cytometer and confocal microscope.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Neuromuscular Research Partnership, Canadian Foundation for Innovation, ALS Society of Canada, the Frick Foundation for ALS Research, CHUM Foundation and Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (C.V.V.). N.A. obtained a Donald Paty Career Development Award from the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada, and both C.V.V. and N.A. are Research Scholars of the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec and CIHR New Investigators. S.P. is supported by the Tim Noël Studentship from the ALS Society of Canada.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Boillee S, Vande Velde C, Cleveland DW. ALS: a disease of motor neurons and their nonneuronal neighbors. Neuron. 2006;52:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sasaki S, Iwata M. Impairment of fast axonal transport in the proximal axons of anterior horn neurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 1996;47:535–540. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.2.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dal Canto MC, Gurney ME. Development of central nervous system pathology in a murine transgenic model of human amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:1271–1279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins CM, Jung C, Ding H, Xu Z. Mutant Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase that causes motoneuron degeneration is present in mitochondria in the CNS. J Neurosci. 2002;22:RC215. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-j0001.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kong J, Xu Z. Massive mitochondrial degeneration in motor neurons triggers the onset of amyotrophiclateral sclerosis in mice expressing a mutant SOD1. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3241–3250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03241.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Browne SE, Bowling AC, Baik MJ, Gurney M, Brown RH, Jr, Beal MF. Metabolic dysfunction in familial, but not sporadic, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurochem. 1998;71:281–287. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71010281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattiazzi M, D’Aurelio M, Gajewski CD, Martushova K, Kiaei M, Beal MF, Manfredi G. Mutated human SOD1 causes dysfunction of oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria of transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29626–29633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tradewell ML, Cooper LA, Minotti S, Durham HD. Calcium dysregulation, mitochondrial pathology and protein aggregation in a culture model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: mechanistic relationship and differential sensitivity to intervention. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;42:265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damiano M, Starkov AA, Petri S, Kipiani K, Kiaei M, Mattiazzi M, Flint BM, Manfredi G. Neural mitochondrial Ca2+ capacity impairment precedes the onset of motor symptoms in G93A Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase mutant mice. J Neurochem. 2006;96:1349–1361. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Q, Vande Velde C, Israelson A, Xie J, Bailey AO, Dong MQ, Chun SJ, Roy T, Winer L, Yates JR, et al. ALS-linked mutant superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) alters mitochondrial protein composition and decreases protein import. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21146–21151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014862107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pedrini S, Sau D, Guareschi S, Bogush M, Brown RH, Jr, Naniche N, Kia A, Trotti D, Pasinelli P. ALS-linked mutant SOD1 damages mitochondria by promoting conformational changes in Bcl-2. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2974–2986. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Israelson A, Arbel N, Da Cruz S, Ilieva H, Yamanaka K, Shoshan-Barmatz V, Cleveland DW. Misfolded mutant SOD1 directly inhibits VDAC1 conductance in a mouse model of inherited ALS. Neuron. 2010;67:575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J, Lillo C, Jonsson PA, Vande Velde C, Ward CM, Miller TM, Subramaniam JR, Rothstein JD, Marklund S, Andersen PM, et al. Toxicity of familial ALS-linked SOD1 mutants from selective recruitment to spinal mitochondria. Neuron. 2004;43:5–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pasinelli P, Belford ME, Lennon N, Bacskai BJ, Hyman BT, Trotti D, Brown RH., Jr Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated SOD1 mutant proteins bind and aggregate with Bcl-2 in spinal cord mitochondria. Neuron. 2004;43:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vande Velde C, Miller TM, Cashman NR, Cleveland DW. Selective association of misfolded ALS-linked mutant SOD1 with the cytoplasmic face of mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4022–4027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712209105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okado-Matsumoto A, Fridovich I. Subcellular distribution of superoxide dismutases (SOD) in rat liver: Cu,Zn-SOD in mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38388–38393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105395200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Igoudjil A, Magrane J, Fischer LR, Kim HJ, Hervias I, Dumont M, Cortez C, Glass JD, Starkov AA, Manfredi G. In vivo pathogenic role of mutant SOD1 localized in the mitochondrial intermembrane space. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15826–15837. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1965-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rakhit R, Robertson J, Vande Velde C, Horne P, Ruth DM, Griffin J, Cleveland DW, Cashman NR, Chakrabartty A. An immunological epitope selective for pathological monomer-misfolded SOD1 in ALS. Nat Med. 2007;13:754–759. doi: 10.1038/nm1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gros-Louis F, Soucy G, Lariviere R, Julien JP. Intracerebroventricular infusion of monoclonal antibody or its derived Fab fragment against misfolded forms of SOD1 mutant delays mortality in a mouse model of ALS. J Neurochem. 2010;113:1188–1199. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bosco DA, Morfini G, Karabacak NM, Song Y, Gros-Louis F, Pasinelli P, Goolsby H, Fontaine BA, Lemay N, McKenna-Yasek D, et al. Wild-type and mutant SOD1 share an aberrant conformation and a common pathogenic pathway in ALS. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1396–1403. doi: 10.1038/nn.2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerman A, Liu HN, Croul S, Bilbao J, Rogaeva E, Zinman L, Robertson J, Chakrabartty A. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is a non-amyloid disease in which extensive misfolding of SOD1 is unique to the familial form. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:335–344. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forsberg K, Jonsson PA, Andersen PM, Bergemalm D, Graffmo KS, Hultdin M, Jacobsson J, Rosquist R, Marklund SL, Brannstrom T. Novel antibodies reveal inclusions containing non-native SOD1 in sporadic ALS patients. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grad LI, Guest WC, Yanai A, Pokrishevsky E, O’Neill MA, Gibbs E, Semenchenko V, Yousefi M, Wishart DS, Plotkin SS, Cashman NR. Intermolecular transmission of superoxide dismutase 1 misfolding in living cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16398–16403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102645108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brotherton TE, Li Y, Cooper D, Gearing M, Julien JP, Rothstein JD, Boylan K, Glass JD. Localization of a toxic form of superoxide dismutase 1 protein to pathologically affected tissues in familial ALS. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:5505–5510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115009109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vande Velde C, McDonald KK, Boukhedimi Y, McAlonis-Downes M, Lobsiger CS, Bel Hadj S, Zandona A, Julien JP, Shah SB, Cleveland DW. Misfolded SOD1 associated with motor neuron mitochondria alters mitochondrial shape and distribution prior to clinical onset. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, Slunt H, Gonzales V, Fromholt D, Coonfield M, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Borchelt DR. Copper-binding-site-null SOD1 causes ALS in transgenic mice: aggregates of non-native SOD1 delineate a common feature. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2753–2764. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lobsiger CS, Boillee S, Cleveland DW. Toxicity from different SOD1 mutants dysregulates the complement system and the neuronal regenerative response in ALS motor neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7319–7326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702230104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mullaney PF, Van Dilla MA, Coulter JR, Dean PN. Cell sizing: a light scattering photometer for rapid volume determination. Rev Sci Instrum. 1969;40:1029–1032. doi: 10.1063/1.1684143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kowaltowski AJ, Cosso RG, Campos CB, Fiskum G. Effect of Bcl-2 overexpression on mitochondrial structure and function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42802–42807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207765200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Metivier D, Dallaporta B, Zamzami N, Larochette N, Susin SA, Marzo I, Kroemer G. Cytofluorometric detection of mitochondrial alterations in early CD95/Fas/APO-1-triggered apoptosis of Jurkat T lymphoma cells. Comparison of seven mitochondrion-specific fluorochromes. Immunol Lett. 1998;61:157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(98)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu X, Arriaga EA. Qualitative determination of superoxide release at both sides of the mitochondrial inner membrane by capillary electrophoretic analysis of the oxidation products of triphenylphosphonium hydroethidine. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:905–913. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson KM, Janes MS, Pehar M, Monette JS, Ross MF, Hagen TM, Murphy MP, Beckman JS. Selective fluorescent imaging of superoxide in vivo using ethidium-based probes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15038–15043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601945103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mukhopadhyay P, Rajesh M, Yoshihiro K, Hasko G, Pacher P. Simple quantitative detection of mitochondrial superoxide production in live cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loew LM, Tuft RA, Carrington W, Fay FS. Imaging in five dimensions: time-dependent membrane potentials in individual mitochondria. Biophys J. 1993;65:2396–2407. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81318-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carriedo SG, Sensi SL, Yin HZ, Weiss JH. AMPA exposures induce mitochondrial Ca(2+) overload and ROS generation in spinal motor neurons in vitro. J Neurosci. 2000;20:240–250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00240.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boillee S, Yamanaka K, Lobsiger CS, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Kassiotis G, Kollias G, Cleveland DW. Onset and progression in inherited ALS determined by motor neurons and microglia. Science. 2006;312:1389–1392. doi: 10.1126/science.1123511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sasaki S, Iwata M. Mitochondrial alterations in the spinal cord of patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:10–16. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31802c396b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins CM, Jung C, Xu Z. ALS-associated mutant SOD1G93A causes mitochondrial vacuolation by expansion of the intermembrane space and by involvement of SOD1 aggregation and peroxisomes. BMC Neurosci. 2003;4:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-4-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sasaki S, Warita H, Abe K, Iwata M. Impairment of axonal transport in the axon hillock and the initial segment of anterior horn neurons in transgenic mice with a G93A mutant SOD1 gene. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2005;110:48–56. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Menzies FM, Ince PG, Shaw PJ. Mitochondrial involvement in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurochem Int. 2002;40:543–551. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(01)00125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raimondi A, Mangolini A, Rizzardini M, Tartari S, Massari S, Bendotti C, Francolini M, Borgese N, Cantoni L, Pietrini G. Cell culture models to investigate the selective vulnerability of motoneuronal mitochondria to familial ALS-linked G93ASOD1. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:387–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tikunov A, Johnson CB, Pediaditakis P, Markevich N, Macdonald JM, Lemasters JJ, Holmuhamedov E. Closure of VDAC causes oxidative stress and accelerates the Ca(2+)-induced mitochondrial permeability transition in rat liver mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;495:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han D, Antunes F, Canali R, Rettori D, Cadenas E. Voltage-dependent anion channels control the release of the superoxide anion from mitochondria to cytosol. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5557–5563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lustgarten MS, Bhattacharya A, Muller FL, Jang YC, Shimizu T, Shirasawa T, Richardson A, Van RH. Complex I generated, mitochondrial matrix-directed superoxide is released from the mitochondria through voltage dependent anion channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;422:515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zimmerman MC, Oberley LW, Flanagan SW. Mutant SOD1-induced neuronal toxicity is mediated by increased mitochondrial superoxide levels. J Neurochem. 2007;102:609–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muller FL, Liu Y, Jernigan A, Borchelt D, Richardson A, Van RH. MnSOD deficiency has a differential effect on disease progression in two different ALS mutant mouse models. Muscle Nerve. 2008;38:1173–1183. doi: 10.1002/mus.21049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferri A, Cozzolino M, Crosio C, Nencini M, Casciati A, Gralla EB, Rotilio G, Valentine JS, Carri MT. Familial ALS-superoxide dismutases associate with mitochondria and shift their redox potentials. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13860–13865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605814103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pesaresi MG, Amori I, Giorgi C, Ferri A, Fiorenzo P, Gabanella F, Salvatore AM, Giorgio M, Pelicci PG, Pinton P, et al. Mitochondrial redox signalling by p66Shc mediates ALS-like disease through Rac1 inactivation. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:4196–4208. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zimmermann AK, Loucks FA, Schroeder EK, Bouchard RJ, Tyler KL, Linseman DA. Glutathione binding to the Bcl-2 homology-3 domain groove: a molecular basis for Bcl-2 antioxidant function at mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29296–29304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702853200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Howland DS, Liu J, She YJ, Goad B, Maragakis NJ, Kim B, Erickson J, Kulik J, DeVito L, Psaltis G, et al. Focal loss of the glutamate transporter EAAT2 in a transgenic rat model of SOD1 mutant-mediated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1604–1609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032539299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prudencio M, Borchelt DR. Superoxide dismutase 1 encoding mutations linked to ALS adopts a spectrum of misfolded states. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:77. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fujisawa T, Homma K, Yamaguchi N, Kadowaki H, Tsuburaya N, Naguro I, Matsuzawa A, Takeda K, Takahashi Y, Goto J, et al. A novel monoclonal antibody reveals a conformational alteration shared by amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked SOD1 mutants. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:739–749. doi: 10.1002/ana.23668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guareschi S, Cova E, Cereda C, Ceroni M, Donetti E, Bosco DA, Trotti D, Pasinelli P. An over-oxidized form of superoxide dismutase found in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with bulbar onset shares a toxic mechanism with mutant SOD1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:5074–5079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115402109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan PH, Kawase M, Murakami K, Chen SF, Li Y, Calagui B, Reola L, Carlson E, Epstein CJ. Overexpression of SOD1 in transgenic rats protects vulnerable neurons against ischemic damage after global cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8292–8299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08292.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vande Velde C, Garcia ML, Yin X, Trapp BD, Cleveland DW. The neuroprotective factor Wlds does not attenuate mutant SOD1-mediated motor neuron disease. Neuromol Med. 2004;5:193–203. doi: 10.1385/NMM:5:3:193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pramatarova A, Figlewicz DA, Krizus A, Han FY, Ceballos-Picot I, Nicole A, Dib M, Meininger V, Brown RH, Rouleau GA. Identification of new mutations in the Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene of patients with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:592–596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]