Abstract

Modified nucleotides are ubiquitous and important to tRNA structure and function. To understand their effect on tRNA conformation, we performed a series of molecular dynamics simulations on yeast tRNAPhe and tRNAinit, E. coli tRNAinit and HIV tRNALys. Simulations were performed with the wild type modified nucleotides, using the recently developed CHARMM compatible force field parameter set for modified nucleotides [Xu, Y., Vanommeslaeghe, K., Aleksandrov, A., Mackerell AD, Nilsson, L., J. Comp. Chem., 2016], or with the corresponding unmodified nucleotides, and in the presence or absence of Mg2+. Results showed a stabilizing effect associated with the presence of the modifications and Mg2+ for some important positions, such as modified guanosine in position 37 and dihydrouridines in 16/17 including both structural properties and base interactions. Some other modifications were also found to make subtle contributions to the structural properties of local domains. While we were not able to investigate the effect of Adenosine 37 in tRNAinit and limitations were observed in the conformation of E. coli tRNAinit, the presence of the modified nucleotides and of Mg2+ better maintained the structural features and base interactions of the tRNA systems than in their absence indicating the utility of incorporating the modified nucleotides in simulations of tRNA and other RNAs.

Keywords: nucleic acids, modified nucleotide, transfer RNA, structure, magnesium, molecular dynamics, simulation, dynamics, divalent ion

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules, which exist in all domains of life, play a central role in protein synthesis. One tRNA brings a specific amino acid and binds to a ribosome, where it is discriminated by matching its anticodon nucleotide triplet with the codon triplet on the messenger RNA (mRNA). If there is a match, the amino acid is incorporated in the nascent peptide chain and the tRNA is released from the ribosome, and the cycle can start over. During the whole process the tRNA interacts with many proteins and RNAs, and both its sequence and conformation are important for proper recognition and function. Furthermore, tRNA molecules are post-transcriptionally modified in several nucleotide positions, some of which are common to all tRNAs, whereas other modifications are specific for a given tRNA species.[1,2,3]

A tRNA consists of 76-96 nucleotides (nt), with modifications occurring in more than 30 positions.[4,5] At least 93 different kinds of modification are identified in tRNA, with marked differences in the types of modifications occurring in archea, bacteria and eukarya.[2,6,7] While the biochemical effects of RNA modifications and the relationship between them and diseases are very elusive, there is strong evidence that the lack of modifications is linked to a number of human diseases.[2,8,9] Generally modifications induce well-defined conformations, which are related to various biological phenomena ranging from regulation of cellular processes while sensing the cell’s metabolic state [1,2] to the numerous interactions between tRNA and other partners in the translational machinery, such as synthetases, ribosomes, mRNA codons, and initiation and elongation factors.[1,5,9,10,11] It is also well established that Mg2+ ions have a crucial role in maintaining the folding of all RNAs, which is necessary for their correct biological function.[12,13,14]

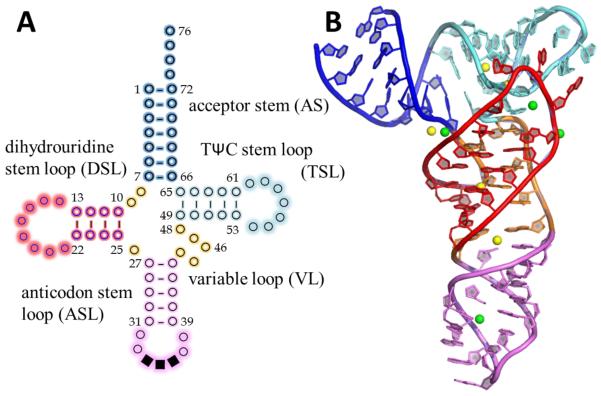

The tRNA secondary structure is cloverleaf shaped (Figure 1A), with five subdomains (Table 1) including the amino acid acceptor stem (AS), the dihydrouridine stem loop (DSL), the anticodon stem loop (ASL), the variable loop (VL) and the TΨC stem loop (TSL). In the L-shaped tertiary structure interactions between DSL and TSL/VL in the “elbow” are stabilized by a cluster of conserved base pairs/triplet layers.[4,10] Some modifications in the anticodon loop (AL) are believed to be responsible for code degeneracy and anticodon-codon conformational stabilization[1,9,11,15,16,17,18] The modifications in other positions are indicated to impact local structural flexibility,[10,12,19] but in most cases their function is still unknown.

Figure 1.

Secondary and tertiary structure of tRNA. A) The secondary clover leaf structure of type 1 tRNAs (shorter VL). Each circle represents a nucleotide, and the anticodon nucleotides are solid squares. Dashes in the stems indicate WC base pairs. Each subdomain is colored differently and labeled. B) The average structure from one simulation of tRNAPhe with modified nucleotides and Mg2+ ions present, showing each subdomain using the same color scheme. Note that nucleotides 73-76 were removed in the simulations. The spheres are Mg2+ ions, where the green ones were in stable positions and the yellow ones were mobile in the simulations.

Table 1.

The notation of nucleotide and tRNA subdomain names

| Nucleotide names | ||

|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Common name | CHARMM name |

| A | Adenosine | ADE |

| +A | Protonated adenosine | ADEP |

| m1A | 1-methyladenosine | 1MA |

| t6A | N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine | T6A |

| ms2t6A | 2-methylthio-N6-threonyl carbamoyladenosine |

12A |

| C | cytidine | CYT |

| m5C | 5-methylcytidine | 5MC |

| Cm | 2'-O-methylcytidine | OMC |

| G | guanosine | GUA |

| m1G | 1-methylguanosine | 1MG |

| m2G | N2-methylguanosine | 2MG |

| m7G | 7-methylguanosine | 7MG |

| Gm | 2'-O-methylguanosine | OMG |

| m22G | N2,N2-dimethylguanosine | M2G |

| yW | wybutosine | YYG |

| U | uridine | URA |

| Ψ | pseudouridine | PSU |

| D | dihydrouridine | H2U |

| m5U , T | 5-methyluridine | 5MU |

| s4U | 4-thiouridine | 4SU |

| mcm5s2 | 5-methoxycarbonylmethyl-2-thiouridine | 70U |

| U | ||

| R | any purine | |

| Y | any pyrimidine | |

| N | Any nucleotide/base | |

| nt | nucleotide | |

| Subdomain names | ||

| ASL | Anticodon stem loop (nt 27-43) | |

| AL | Anticodon loop (nt 32-38) | |

| DSL | Dihydrouridine stem loop (nt 10-25) | |

| DL | Dihydrouridine loop (nt 14-21) | |

| TSL | TΨC stem loop (nt 49-66) | |

| TL | TΨC loop (nt 54-60) | |

| VL | Variable loop (nt 44-48) | |

| AS | Acceptor stem (nt 1-7 & 66-72) | |

From crystallographic studies the spatial arrangement of several tRNA modifications have been elucidated,[20,21,22,23] but their impact on the dynamics is more elusive. Alternatively molecular dynamics (MD) simulation and modeling methods[24,25,26] may be used to obtain a detailed picture of the structural and energetic effects of modified nucleotides. Classsical MD simulations model the interactions between all atoms in the system (macromolecule + solvent) with an empirical approximation (a force field) to the true quantum-mechanical energy surfce, which is used to solve Newton’s equations of motion for all the atoms. The trajectory thus obtained is with today’s computers typically 0.1 – 1.0 μs long, and from this Bolztmann weighted sample of accessible conformations in the vicinity of the native structure a variety of structural properties are readily computed. The high charge density of nucleic acids was initially a problem and the method was mainly applied to proteins, but advances in computing power and simulation protocols over the last two decades now allows the study of both DNA and RNA systems.[27]

Previous simulation studies of tRNAs have focused on the ASL and codon-anticodon interactions.[28,29,30,31] In the present manuscript we report MD simulations of select tRNAs using the CHARMM36 force field[32] that was recently extended to included modified nucleotides. The simulations are designed to investigate the influence of the nucleotide modifications on tRNA structure and dynamics as well as the impact of Mg2+. Simulations were performed on yeast tRNAPhe and tRNAinitMet, E. coli tRNAinitfMet, and HIV tRNALys. All systems were studied in the presence and absence of the modified nucleotides, and in the presence and absence of Mg2+. We compared the structures with respect to overall conformation, local structural deviations, base stacking, and hydrogen bonding patterns. The modifications in important subdomains like the A and D loops are confirmed to contribute maintaining the conformational features, and the direct stabilizing effect of several Mg2+ ions is also demonstrated.

2. Methods

2.1. Structure preparation

The crystal structures of yeast tRNAPhe (1EHZ)[21], yeast tRNAinit (1YFG)[20], E. coli tRNAinit (3CW5)[33] and HIV tRNALys (1FIR)[23] were obtained from the PDB. Together these four structures contain 19 different modified nucleotides, of which 17 are discussed in this manuscript (Table 1). Each tRNA was simulated either as the wild type structure with all modifications present (WT), or as a modeled structure with all modified nucleotides replaced by their canonical counterparts (CAN). Crystal ions and crystal water were not included in these systems, except for 1EHZ, which has two extra systems: the wild type and canonical structures with crystal divalent ions and water, respectively (WTMG and CNMG). For lack of parameters, two manganese ions in 1EHZ were replaced by magnesium (Mg2+) and the updated parameters for Mg2+ were used.[34] Each system was subjected to two independent runs, each with duration of 300 ns. Since the amino acid binding site is not related to the nucleotide modifications, to reduce the system dimension, the terminal unpaired nucleotides were removed from the starting structures (i.e. nt 73-76 in 1EHZ, 1YFG and 1FIR; nt 1 and nt 72-76 in 3CW5).

2.2. Molecular dynamics simulations

All calculation and simulations were performed with the program CHARMM[24] with the CHARMM/OpenMM GPU interface,[35] allowing production runs of ~25 ns/day for the ~76000-atom systems. The CHARMM36 force field for nucleic acids,[36,37] including the recent extension for modified nucleotides[32] and the CHARMM General Force Field[38,39] were used.

After adding hydrogen atoms on the crystal structures, 100 steps of steepest descent (SD) energy minimizations were performed with all non-hydrogen atoms restrained with a harmonic force constant of 80 kcal/mol/Å2. This was followed by 200 steps of adopted basis Newton Raphson (ABNR) minimizations with 40 kcal/mol/Å2 restraints on backbone non-hydrogen atoms, and then two 300-step ABNR minimizations with backbone restraints of 10 and 5 kcal/mol/Å2, respectively. For WTMG and CNWG, to avoid Mg2+ structural deviations during the minimizations, only two minimizations were done: 1) 100 steps SD with 104 kcal/mol/Å2 harmonic restraints on non-hydrogen atoms and 2) 300 steps ABNR with 103 kcal/mol/Å2 restraints on backbone non-hydrogen atoms along with 100 kcal/mol/Å2 restraints on non-hydrogen atoms of all crystal waters, Mg2+ and bases.

All structures then were solvated using the TIP3P water model[40] in a cubic box of 90 Å side length, with periodic boundary conditions applied. Na+ ions to neutralize the negative phosphate charges of the RNAs, and another 65 pairs of Na+ and Cl− ions were added to attain a 0.15 M concentration of NaCl. The particle mesh Ewald method[41] was applied for long range electrostatic interactions, with a direct space cutoff of 10 Å, and a switch function (vfswitch) over the range 8.5-10 Å was used for van der Waals interactions.[42] Following solvent overlay a 150-step SD and a subsequent 800-step ABNR minimization were performed, with 80 kcal/mol/Å2 harmonic restraints on non-hydrogen tRNA atoms. For WTMG and CNMG, the same minimization procedure was performed but with a 103 kcal/mol/Å2 harmonic restraint on the tRNA and 20 kcal/mol/Å2 on Mg2+.

The systems were gradually heated from 48K to 298K within 70 ps in the NPT ensemble. For WTMG and CNMG no heating was applied; instead, the systems were equilibrated with four 200 ps runs with 103 kcal/mol/Å2 harmonic restraints applied to tRNA non-hydrogen atoms, and Mg2+ restraints of 20, 10, 5 and 0 kcal/mol/Å2, respectively in the four runs. This was followed by 1 ns equilibrium simulation with all tRNA non-hydrogen restrained by 5 kcal/mol/Å2. The production simulations were performed in the NVT ensemble using Langevin dynamics with a friction coefficient of 5 ps−1. The leap-frog integrator was used with a 2 fs timestep. Bonds involving hydrogen atom were constrained using the SHAKE algorithm[43]. All other restraints were removed except the 5 kcal/mol/Å2 distance restraints on N1-N3 of WC basepair R1:Y72 (1EHZ, 1YFG and 1FIR) or R2:Y21 (3CW5), to avoid edge effects due to the truncation of the terminal bases. The trajectories were written out every 10 ps.

2.3. Conformational definitions and analysis

The root mean square deviation (RMSD) of coordinates was calculated by superimposing non-hydrogen atoms of each snapshot on the starting structure, as follows: for ASL the ASL atoms (Table 1) were superimposed, and for DSL and TSL the atoms of the D stem (nt 10-13, 22-25) and T stem (nt 49-53 and 61-66) were superimposed. The glycosidic torsion (χ), which is about the base-ribose linkage, was defined by the dihedral O4′-C1′-N1-C2 (pyrimidine), O4′-C1′-N9-C4 (purine) or O4′-C1′-C5-C4 (pseudouridine), and its conformation is denoted as anti for 170° < χ < 300° (where χ < 220° is low anti and > 270° is high anti) and as syn for 30° < χ < 90°. The ribose pucker was defined by the pseudorotation phase angle P,[44] and in this paper it was simply denoted as north (−90° < P ≤ 90°) and south ( 90° < P ≤ 270°). The criteria of base stacking are similar as previously published[32]: 1) the distance between two glycosidic nitrogen atoms R ≤ 5 Å; 2) the pseudo dihedral formed by two base-axis atoms, i.e. N1-C4 of Y or N9-C6 of R, (Φ0 – 40°) ≤ Φ ≤ (Φ0 + 40°); and 3) the angle between normal vectors of the two bases, Θ ≤ 40° or Θ ≥ 140°, where Φ0 is the value when two bases are stacking in the ideal A-RNA geometry (Φ0 ≈ 20° for 5′-R-R-3′ or 5′-Y-Y-3′, Φ0 ≈ 40° for 5′-R-Y-3′ and Φ0 ≈ 0° for 5′-Y-R-3′ context). We monitored the existence of base pairs through the presence of N1-N3 (WC base pairs) or N7-N3 (Hoogsteen base pairs) hydrogen bonds, using the criterion r(acceptor-donor) < 3.5Å. The existence of other base pairs was identified if the distance between one pair of original acceptor and donor atoms is less than 3.5Å.

3. Results

Four tRNAs were selected to investigate the impact of the presence of the modified nucleotides and of Mg2+ on their structural properties as well as to validate the recently published CHARMM parameters for modified nucleotides.[32] The four tRNAs have the same sequence length in ASL, TSL and AS. The only length difference is in the DSL where 1EHZ and 1FIR have the standard 8 nucleotides in the loop, whereas 1YFG and 3CW5 have 7 and 9 nucleotides, respectively. There are 11, 14, 5 and 15 modified nucleotides in 1YFG, 1EHZ, 3CW5, and 1FIR, respectively. Together the four tRNAs cover 19 RNA modifications (m1G, s4U, m2G, D, m22G, Ψ, Cm, Gm, mcm5s2U, t6A, ms2t6A, +A, yW, m5C, m7G, T, Tm, m1A and r(p)A). We note that the present simulations are performed in solution, such that the lack of crystal packing effects present in the experimentally determined structures may impact the obtained results.

3.1. Overall structural stability of all tRNAs

All structures reached equilibrium within 50 ns and the coordinate RMSDs from their respective crystal structure were stable around 3-5 Å for the entire structures (Table 2, Figure S1). In the four 1EHZ systems RMSDs were similar whereas the RMSDs in 1YFG, 3CW5 and 1FIR were typically lower for WT than for CAN. The overall RMSD being less for WT than for CAN is consistent with the expected stabilization of the modifications in the tRNA structures.

Table 2.

The average coordinate RMSD (Å) over the last 250 ns of each system.

| System and run | All | ASL | DSL | TSL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1EHZ | WT | r.1 | 3.9 | 1.8 | 3.4 | 2.5 |

| r.2 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 1.8 | ||

| CAN | r.1 | 3.9 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 2.7 | |

| r.2 | 4.2 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 2.6 | ||

| WTMG | r.1 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 2.2 | |

| r.2 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.9 | ||

| CNMG | r.1 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.9 | |

| r.2 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 2.2 | ||

|

| ||||||

| 1YFG | WT | r.1 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 1.5 |

| r.2 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 1.7 | ||

| CAN | r.1 | 4.6 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 2.1 | |

| r.2 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 2.3 | ||

|

| ||||||

| 3CW5 | WT | r.1 | 3.8 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 1.8 |

| r.2 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 1.6 | ||

| CAN | r.1 | 5.3 | 1.9 | 6.8 | 3.6 | |

| r.2 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 3.8 | 1.7 | ||

|

| ||||||

| 1FIR | WT | r.1 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 2.5 | 1.2 |

| r.2 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 2.6 | 1.3 | ||

| CAN | r.1 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 1.4 | |

| r.2 | 5.0 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 2.0 | ||

3.2. Conformation and base stacking of the anticodon

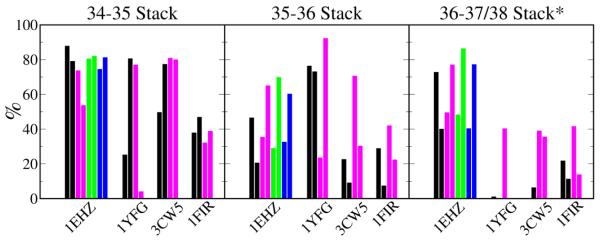

In the folded 3D structures, the DSL, TSL and VL form the elbow, while the AS and ASL form the arms of the L shaped tRNA. When we superimpose only the ASL atoms (nt 27-43) the RMSDs are as low as 3 Å except 1FIR (Table 2), which suggests only a moderate change in the ASL conformation. Thus, the relative orientation of the ASL with respect to the AS is what leads to the higher RMSD for the whole structure. The RMSD of the ASL is similar between WT and CAN, except in 1EHZ where WT and WTMG are more stable than CAN and CNMG after 200 ns (Figure S1). The bending of ASL is assumed to be required for ribosomal tRNA recognition, where the tRNA bends into the A/T state to contact the A-site of the small subunit[45]. The conformation of the loop in the ASL (nt 33-37) was monitored in the simulations. With the exception of A37 in 1YFG, 3CW5 and 1FIR, χ and P of all nucleotides remained in the crystal conformation (Figure S2), i.e. strictly low-anti and north, which is a standard A-helix conformation and present in codon:anticodon interaction on ribosomes. The purines at positions 37 are different in each case and will be discussed below. However, even though the conformation of all the anticodon loops was relatively rigid, their interactions were different. Figure 2 shows the fraction of base stacking between the anticodons and their 3′-purines. For 1EHZ stacking in WT was similar to that in CAN, with WTMG showing a small increase over WT. In 1FIR, WT had better 34-35 stacking than CAN, and no obvious difference for the other two base steps. On the other hand, the replicates in 1YFG and 3CW5 were less consistent, especially for the CAN simulations. A common feature in 1YFG and 3CW5 is the lack of 36-37 stacking, which is consistent with the crystal structures in which A37 is not in the base stack of the A loop. Instead U36 in 3CW5 stacks with A38. The present simulations show such stacking in CAN (A38) but not in WT (+A38), whereas in 1YFG A37 in one of the CAN simulations moved into the base stack of the A loop and stacked with U36.

Figure 2.

The percentage of base stacking in the anticodon of each run. Color scheme is black (WT), magenta (CAN), green (WTMG) and blue (CNMG).*36-37 stack for 1EHZ, 1YFG and 1FIR; 36-38 stack for 3CW5.

3.3. Conformation of the D loop

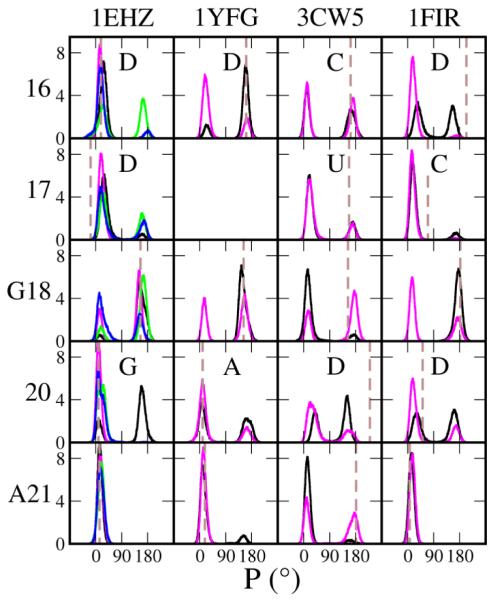

To keep the correct folding of the tRNA tertiary structure, DSL participates in tight and essential interactions with TSL and VL. For this reason, we analyzed the RMSDs of DSL and TSL together by superimposing both D and T stem atoms. For DSL the systems that included Mg2+ has slightly lower RMSDs in 1EHZ, and WT consistently was more stable than CAN for 1YFG and 1FIR (Table 2). While TSL has the lowest RMSDs for all the subdomains in all four tRNAs, the RMSD was larger in CAN than in WT. The main difference between WT and CAN in DSL is the presence of D which is highly conserved in this subdomain, where D is found in positions 16, 17 and/or 20, and whose bases are unpaired and oriented towards the solvent. In contrast, the neighbors of D (i.e. nt 15, 18, 19 and 21), are all interacting with bases in TSL and VL in various ways to maintain the tRNA architecture. In 1EHZ D16 and D17 are not in their usual south conformation but north. This conformation was present in both WT and CAN simulations, but in the MG simulations the ribose pucker also samples south to some extent (Figure 3). D16 in 1YFG and 1FIR, and D20 in 3CW5 all sample mostly the south pucker, consistent with that observed in the crystal structures, whereas their counterpart Us in CAN sampled primarily the north pucker. With the exception of 3CW5, the modified D16/17 nucleotide rather than U16/U17 leads to sampling of south for G18, which is a conserved guanosine that hydrogen-bonds with Ψ/U55 and stacks between 57 and 58 in the T loop. The exception in 3CW5 is because of the unstable local structure of WT where G18 lost both the hydrogen bonding and stacking interactions.

Figure 3.

The sugar pucker distributions of nucleotides in the D loop from the simulations. The columns from left to right show 1EHZ, 1YFG, 3CW5 and 1FIR, respectively; rows from top to bottom show nucleotides 16, 17, G18, 20 and A21 respectively. The WT nucleotides in positions 16, 17 and 20 are shown in the individual panels. The combined distributions from two independent runs of each system are shown in the graphs. Color scheme is black (WT), magenta (CAN), green (WTMG) and blue (CNMG). The conformation in the crystal structure is shown as a vertical brown dashed line in each panel.

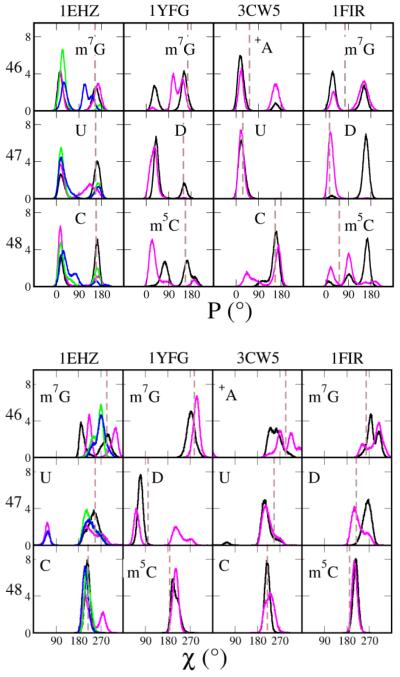

3.4. Conformation of the V loop

All tRNAs in this study have a short variable loop comprised of 3 nucleotides. As with the D loop, this loop is a small bulge where D/U47 is solvent exposed, while R46 and Y48 participate in the elbow fold. In 1EHZ the three nucleotides in this subdomain have south puckers, which we also observed in WT (Figure 4, upper panel). South conformations are sampled in 1YFG, but here both WT and CAN sample predominately north at nt 47, while for 46 and 48 WT sampled more south, consistent with the crystal structure. Similarly in 1FIR the population of south for the three nucleotides was higher in WT than in CAN. Note that in 1FIR, apparently due to the resolution of the crystal structure, intermediate pucker values between north and south are present, which are not observed in the other tRNAs. In terms of χ, the four structures were similar. Because of base pair formation, both 46 and 48 need to be anti and this was observed in all simulations (Figure 4, lower panel). In 1YFG D47 in WT better reproduced syn than CAN indicating the importance of that modification.

Figure 4.

The sugar pucker (top) and glycosidic torsion (bottom) distributions of nucleotides in the V loop from the simulations. Within each graph, the columns from left to right show 1EHZ, 1YFG, 3CW5 and 1FIR, respectively; rows from top to bottom show nucleotides 46, 47 and 48, respectively. The WT nucleotides are shown in the individual panels. The combined distributions from two independent runs of each system are shown in the graphs. Color scheme is black (WT), magenta (CAN), green (WTMG) and blue (CNMG). The conformation in the crystal structure is shown as a vertical brown dashed line in each panel.

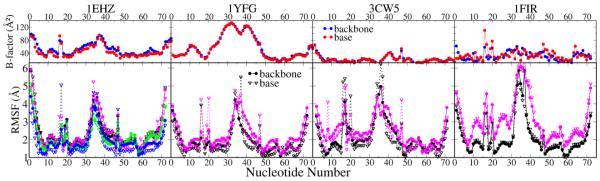

3.5. Structural fluctuations

The patterns of the RMS fluctuations are quite similar in the four tRNAs (Figure 5), with larger fluctuations occurring in the terminal residues than for residues in the central regions. As expected the fluctuations were larger in the loops than in the stems, with the AL having larger fluctuation than the other loops. The experimental B-factors provide a proxy for structural “rigidity”, and the observed fluctuation patterns are generally consistent with the B-factors for 1EHZ and 1YFG (Figure 5), but to a lesser extent for 3CW5 and 1FIR. This is potentially due to their B-factor distributions being significantly impacted by crystal packing contacts. In 1EHZ WT and CAN were quite similar, while in other systems, the average fluctuations in WT were smaller than in CAN (Table S2), especially for bases in the loops. Generally, in the stems the base fluctuations were smaller while in loops the backbone atoms fluctuated less. Several bulge positions, like 16/17/17a, 20 and 47, had significant base fluctuations, nevertheless their neighbor nucleotides still kept low fluctuations. This suggests that the local region surrounding those bulges were stable in the simulations. Particularly A37 in 1YFG, 3CW5 and 1FIR had large fluctuations as it is not participating in base stacking.

Figure 5.

The root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) as a function of the nucleotide sequence (bottom) compared with the average experimental B-factors (top). The columns from left to right show 1EHZ, 1YFG, 3CW5 and 1FIR respectively. The graphs show averages from two independent runs of each system. Color scheme for B-factor is blue (backbone) and red (base); for RMSF it is black (WT), magenta (CAN), green (WTMG) and blue (CNMG); solid circles and lines, and open triangles and dashed lines, are used for backbone and base atoms, respectively.

4. Discussion

Based on the observed coordinate deviations, nucleotide conformations, anticodon stacking and atomic positional fluctuations, the major outcomes of the present simulations may be summarized as follows: 1) 1EHZ was the most stable structure in all simulations, possibly as a result of its higher structural resolution (1EHZ: 1.93 Å; 1YFG: 3 Å; 3CW5: 3.1 Å and 1FIR: 3.3 Å); 2) the 3CW5 structure differs from the other three, thus in the simulations several features which are common to 1EHZ, 1YFG and 1FIR are missing in 3CW5; 3) overall, as well as for most local domains, WT simulations show lower RMSDs than CAN simulations indicating the importance of the modified nucleotides in maintaining the overall conformations of the tRNAs. The presence of Mg2+ ions also lead to the simulations yielding smaller RMSDs.

4.1. Stability of the A loop

The presence of the modified nucleotides shows differences in the ASL. 1EHZ and 1FIR have modified nucleotides in the anticodon wobble position, Gm34 and mcm5s2U34, respectively. Although Gm34 in one WT simulation changed from anti to syn, its pucker still remained north compared to CAN (Figure 2S), and the 34-35 stacking is also more persistent than for G34 (Figure 2). In the force field stabilization of north pucker and stacking by the 2′O-Me is not significant.[32] This is consistent with the experimental thermal stability and codon binding affinity of ASLPhe being comparable for Gm34 and G, but Gm34 does enhance the binding between ASLPhe and ribosomal 16S rRNA.[46,47] In 1FIR mcm5s2U34 sampled predominantly anti/north as compared to U34 (Figure 2S) and it also stacked slightly better (Figure 2). The pronounced enhancement of north and stacking by s2U derivatives has been demonstrated in several experimental studies.[48,49,50,51]

R37 is an interesting anticodon nucleotide concerning modifications, many of which are considered to order the anticodon triplet, and help keeping the correct reading frame.[11] In simulations of 1EHZ, yW37 was less mobile than the canonical G37 (Figure S3, Table S2). A restricted mobility of yW37 was observed in 13C-NMR experiments [52], where it has the least mobile methyl groups as compared with m7G46, T54 and m1A58. Here we observed two conformations of ASLPhe in equilibrium. The dominant one is similar to that in the crystal structure where nucleotides 34, 35, 36 and 37 are stacked while in the other conformation A36 bulged out and lost its stacking with 35 and 37. In the first case the side chain carbonyl O of yW37 formed a hydrogen bond with A36 or A35, and enhanced the stacking for nucleotides 34 to 37 more than G37 in CAN/CNMG. In the second case yW37 was hydrogen bonded only with A35, and the latter stacked with Gm34, thus except for A36 the other nucleotides were still less mobile. A36 also bulged out in CAN/CNMG, but without the modification the induced motions of A35 and G37 were very large and it took longer for them to return to their original positions (Figure S3, Table S2).

Nucleotide 37 in 1YFG and 1FIR is t6A37 and ms2t6A37, respectively, and both have the same modification on N6 of the base. In the crystal structure, while t6A37 in 1YFG is outside the base stack, possibly because of crystal packing. ms2t6A37 of 1FIR is inside and the base stacking of nucleotides 34-37 is regular. However, both these ASLs did not form a stable regular base stack, with or without the modification. In 1YFG, ASL was ordered during part of the simulation, but the dominant state was with the base bulged out. Because of the high base mobility, the stacking behavior varied between base steps and between replicate runs. In 1FIR, ms2t6A37 improved the stacking with A38 rather than with U36, and there was no interaction between the ms2t6A37 side chain and U36/U35. Hence, although mcm5s2U34 slightly improved the stability of the A loop, stacking of 35-36 and 36-37 was better in the CAN simulations. Experimentally (ms2)t6A37 has been found to order the AL to bind a cognate codon in the ribosomal A-site, but to increase the flexibility by not allowing the hydrogen bond between U33 and A37[53,54]. This difference in behavior between A37 and U33 was also observed between the corresponding nucleotides in the WT and CAN simulations of both 1YFG and 1FIR, which suggests that the flexibility of ASL is not unphysical. Furthermore the experimental conformation of (ms2)t6A37-ASL is not unique. Different from 1FIR, (ms2)t6A in other free tRNAs is in a tri-cyclic conformation, with an intra-residue hydrogen bond formed between N1 and H11, and it does not stack with U36 and A38 simultaneously, often accompanied by a bulged-out U36.[53,55,56]. In contrast, all (ms2)t6A37-ASL in ribosome-bound tRNAs are well ordered and disposed to interact with the mRNA, where (ms2)t6A37 is stacking with the U36:A1(codon) base pair, and an extra hydrogen bond becomes possible between (ms2)t6A37 and A1.[57,58]

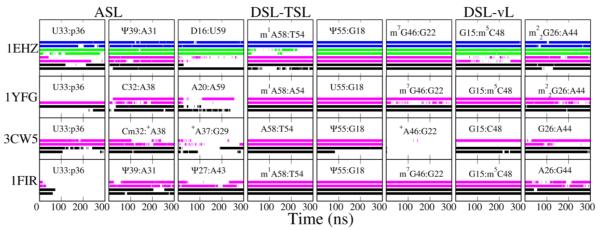

A37 and A38 are supposed to be protonated in 3CW5 at the experimental pH,[33] and involved in a special ASL structure where +A37 binds to the Hoogsteen side of G29, and +A38 forms a WC-like base pair with Cm32. This ASL conformation is flexible in the present simulations. The interaction of A37:G29 fluctuates in both protonated (WT) and neutral (CAN) cases (Figure 6, 3rd col.), such that A37 can also interact with G30. Protonation makes this interaction more stable. However, the WC-like base pair of A38:Cm32/C32 is not stable in either WT or CAN. Instead this base pair changed to the so-called bifurcated geometry as most tRNAs usually have[59], with a stable hydrogen bond from N6 of A38 to N3/O2 of Cm32. The bifurcated A-C pair also exists in 1YFG and was maintained in the simulation (Figure 6, 2nd col.). Both 1YFG and 3CW5 are initiator tRNAs, and the bulged-out R37 is also observed in another non-ribosomal tRNAinit[60].

Figure 6.

Hydrogen bonds for base pairs in each trajectory vs simulation time. The rows from top to bottom show 1EHZ, 1YFG, 3CW5 and 1FIR, respectively. The colored strip indicates that the hydrogen bonds in the base pair are present. The first two columns show base pairs in ASL, the middle three columns (except 3rd col. in 3CW5 and 1FIR) are base pairs in TSL or between DSL and TSL, and the last three columns are base pairs between DSL and VL. Color scheme: black (WT), magenta (CAN), green (WTMG) and blue (CNMG).

An important aspect of AL stability is the uridine turn led by U33, which is an essential feature to maintain an ordered anticodon conformation.[61]. There is a conserved hydrogen bond between the U33 base and the N36 phosphate; if N35 is a purine then an extra hydrogen bond is also present between the U33 sugar and the N35 base. Among the four structures, 1EHZ sampled the U-turn conformation in all simulations except CAN (Figure 6, 1st col.), while for 1YFG it was intermittent in both systems; in 3CW5 CAN was better than WT, and in 1FIR the U-turn was lost in both WT and CAN. This is consistent with the observations of anticodon stacking and nucleotide mobility in the above context.

1EHZ, 1YFG and 1FIR have a hypermodified R37, but only yW37 in 1EHZ evidently contributed to ASL structural stability. One reason is that the three anticodon nucleotides in 1EHZ (GAA) are purines, which support batter stacking than pyrimidines and form one more hydrogen bond in the U-turn; this advantage is clear when comparing the CAN simulations between 1EHZ and 1FIR (UUU anticodon). The second reason is that yW37 directly interacts with A35/A36 that contributes to stability. While there is no interaction between U36 and (ms2)t6A37, (ms2)t6A37 participates in stabilizing interactions only when the base pair U36:A1 is formed on the ribosome. Thus the function of R37 is to maintain the stacking with the first anticodon:codon base pair. The chemical variations of R37 might depend on nucleotide 36. Importantly there are several crystal packing contacts present in ASL and DSL in 1YFG, 1FIR and, especially, 3CW5. This may induce conformations that are not significantly sampled in solution, and therefore not reproduced in the MD simulations.

4.2. The effect of dihydrouridine

Dihydrouridine is the only modification that is present in all four tRNAs, and its flexibility and south pucker in an RNA context are well documented.[62,63] D is always found in positions 16, 17, 20 (in the D loop), and 47 (in the V loop), etc. In this report a consistent effect of D16/D17 in 1EHZ, 1YFG and 1FIR is inducing sampling of south in G18, even though D16/17 in 1EHZ sampled predominately north (Figure 3). Contrary to the conventional notion that D destabilizes the RNA A-helical conformation, the south conformation is probably necessary in some non-canonical motifs. Considering that G18/G19 are predominantly south in crystal structures, that base pairs G18:U55 and G19:C56 are highly conserved[10], and that dihydrouridines 16/17 and 20 are positioned at kinks before and after which nucleotides 10-15 and 21-25 are in canonical A-helices, the role of D in those two positions may be to decrease the entropic cost of distorting the D loop to allow binding to the T loop. This is supported by experiments in which D16 is required for stable hairpin formation in DSL-mimicking oligonucleotides, whereas with U16 there is much conformational interconversion.[64] In contrast, G18 in WT of 3CW5 sampled north more than in CAN, and an unexpected loss of a hydrogen bond in G18:Ψ55 happened in one run (Figure 6, 5th col.) and caused local destabilization. It is not clear whether the absence of D in position 16/17 is related to some special function of E. coli tRNAinit. It has recently been shown that E. coli dihydrouridine synthase C can modify both U16 and U20 based on different sets of binding identifications.[65] Probably E. coli tRNAinit (3CW5) avoids modification by synthase C by not using U in position 16 so that it can fold into a unique architecture, which is different from elongator tRNAs and yeast tRNAinit.

In all four tRNAs, while nucleotide 20 displayed different north/south ratios in WT and CAN, A21 was always in north. We are not sure that the south pucker of A21 observed in the crystal structure (3CW5) is structurally specific or just due to low resolution; since A21 is stacking with the D stem, north would be a reasonable conformation. As a consequence, even though D20 is present in 3CW5 and 1FIR, A21 is in the standard north conformation, which is opposite to what we observe for nucleotides 16-18. Thus the preference for south induced by D for nucleotides on its 3′ side is not absolute; it is more that D softens the local conformation of the RNA strand to allow favorable loop interactions.

4.3. The effect of pseudouridine

Ψ increases the rigidity of A-type helices.[66,67,68,69] Concerning the four simulated tRNAs, all Ψs exist in rigid subdomains, in positions 39 (A stem) and 55 (T loop), and all stay in the low-anti and north conformations during the simulations. The loss of the hydrogen bond Ψ55:G18 in 3CW5 is mainly because of the destabilization of the D loop as discussed above. Nevertheless most of their canonical counterparts also have the same conformation and maintain the corresponding hydrogen bonds (Figure 6, 2nd and 5th col.). The only obvious stabilization advantage of Ψ over U is in Ψ27:A43, the first A stem pair of 1FIR (Figure 6, 3rd col), And correspondingly the upper base pair of junction A26:G44 was also less stable in CAN (Figure 6, 8th col.). Admittedly this is located in the junction where the conformation is relatively flexible, and the motion of nearby base pairs might also affect A26:G44.

4.4. Effect of base methylation

Methylation is the most abundant modification in RNA. It primarily changes the molecular size and hydrophobicity and also influences the base aromaticity. The accumulation of methylations lowers the biomolecular rigidity and activation energy in aqueous phase, thus methylation has been hypothesized to be a promoter of an evolutionary path where the information storage and catalytic functions of RNA eventually are transferred to methyl-abundant DNAs and proteins, respectively.[70] Specifically a large number of experiments have studied the activities of methylation enzymes of tRNA,[71,72,73,74] as well as the methylation influence on tRNA function.[52,75] However it is difficult to attribute structural changes to methylation directly using current models, because some effects of methylation are not straightforward. Indeed several methylated base pairs in WT performed better than CAN, for example, m5C48 in 1EHZ, m7G46 and m22G26 in 1YFG (Figure 6, 6-8th col.). A direct benefit of a methylated base is the improved stacking; also charged bases like m7G have stronger hydrogen bonding ability[76]. Those effects together may have positive contribution to WT structures. However, as other systems, e.g. m7G46 in 1EHZ, m5C48 in 1YFG and 1FIR, were fairly stable in both WT and CAN, the significance of methylation cannot be fully elucidated.

An unexpected destabilization happened in base pair m1A58:T54 in 1EHZ (Figure 6, 4th col.). The base pair also exists in 1FIR, and although it was more stable compared with 1EHZ, small fluctuations were still present in WT rather than in CAN (data not shown). However m1A58:A54 in 1YFG was consistently stable in both WT and CAN. As with m7G, the charged base enhances the hydrogen bonds with another base.[76] Thus the destabilization in WT likely suggests a limitation of the force field. This might be from the underestimated T54-Ψ55 stacking and/or m1A58:T54 hydrogen bonding.

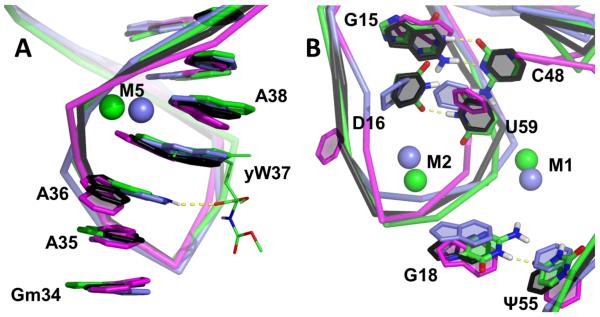

4.5. Effects of Mg2+

The contribution from Mg2+ to the stabilization of the AL and DL is clear. There are 9 divalent metal ions in the crystal structure 1EHZ (numbered M1-M9). In simulations only the four ions which directly bind to phosphate remained in their original positions, while the other five, hexa-coordinated to water, were mobile and diffused around the structure (Figure 1B). The four stable ions (M1, M2, M5 and M7) are located at G20/A21, G19, yW37 and U7/A14. They stabilized not only the contacted nucleotides in direct contact but also the backbone in the DSL and ASL (Figure 7). One example of stabilization by Mg2+ is M5 in the A loop (Figure 7A). It anchors to the phosphate of yW37 and follows the backbone motion. As a consequence the WTMG simulation shows the most rigid anticodon conformation (Figure S2), the smallest RMSD (Table S2) and the most base stacking when A36 was not bulged out. The stability improvement is larger when both the Mg2+ and nucleotide modifications are present, which suggests that the effects of modification and Mg2+ are combined. This agrees with experiments of binding affinity showing that yW37 stabilizes the AL together with Mg2+.[77] This position of divalent ions is rather conserved and has been reported in free tRNAPhe [78,79]. Another highly conserved ion site is M2 between G19 and D16, which keeps the latter interacting with U59 (Figure 7B). Five confirmed divalent ions are present in DSL that help to maintain the tRNA tertiary structure. The interactions between D/T loops are complicated, and in addition to the conserved base pairs G18:U55 and G19:C59, there are also non-standard interactions, such as D16:U59 in tRNAPhe. This is a non-planar and weak base pair. The hydrogen bond occupancy shows that in the presence of Mg2+ both D/U16:U59 were kept, while without Mg2 the base pair was less stable (Figure 6, 3rd col.).

Figure 7.

The local structure of tRNAPhe (1EHZ) showing some modifications involving base pairs and magnesium ions. Each average structure of (A) A loop and (B) D loop was superimposed on the crystal structure. Color scheme is black (WT), magenta (CAN), green (WTMG) and slate (crystal); CNMG is not shown. The Mg2+ ions (spheres) have the same color as the tRNA. Some bases in WTMG are shown in atomic detail for visualization of hydrogen bonds (yellow dashed line).

5. Conclusion

We performed a total of 6 μs of MD simulations on four tRNAs, with or without nucleotide modifications, and in one case also with Mg2+ ions. The results showed that yW37 combined with a Mg2+ in the anticodon loop contributes to the stabilization and rigidity of the anticodon in tRNAPhe, and Gm34 and Cm32 may also contribute to the stabilization. D16/D17 enabled the D loop backbone to fold into the necessary conformation to order the base stack and base pair which are necessary for interactions between the D arm and the T/V loops. In addition, at least one Mg2+ contributed to stabilizing the D loop. Some base-methylated nucleotides like m5C, m7G and m22G exhibited slightly improved hydrogen bonding compared to the corresponding unmodified nucleotides. The strong stabilization of Ψ was not observed, since the U-counterparts had similar structural properties. The (ms2)t6A modifications in 1YFG and 1FIR were not found to improve the stability of the anticodon in free tRNA. It may however be that the modification contributes to the stabilization of the anticodon:codon mini-helix formed on the ribosome. We did not observe any impact on the tRNA structure of the adenosine protonation in E. coli tRNAinit.

Overall, the present simulations indicate a role for many of the modifications in maintaining the structure of tRNAs and impacting their dynamic properties. In addition, Mg2+ is again indicated to be important for stabilization of tRNA, including specific ion-RNA interactions. The results also act as a validation of the recent extension of the CHARMM36 force field to modified nucleotides.[32] However, in some cases differences between the simulated and experimental local conformations in the regions of the modifications were observed. Such differences may indicate limitations in the force field although the impact of the limited duration of the simulations as well as the influence of crystal packing effects cannot be excluded.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Financial support for this work was provided by NIH grants GM070855 and GM051501 (to A.D.M.), the Swedish Research Council (to L.N.), and the China Scholarship Council and the Karolinska Institutet Board of Doctoral Education (to Y.X.).

References

- [1].Helm M, Alfonzo JD. Posttranscriptional RNA Modifications: Playing Metabolic Games in a Cell's Chemical Legoland. Chemistry & Biology. 2014;21:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Carell T, Brandmayr C, Hienzsch A, Muller M, Pearson D, Reiter V, Thoma I, Thumbs P, Wagner M. Structure and function of noncanonical nucleobases. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:7110–7131. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cantara WA, Crain PF, Rozenski J, McCloskey JA, Harris KA, Zhang XN, Vendeix FAP, Fabris D, Agris PF. The RNA modification database, RNAMDB: 2011 update. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:D195–D201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Giege R, Juhling F, Putz J, Stadler P, Sauter C, Florentz C. Structure of transfer RNAs: similarity and variability. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Rna. 2012;3:37–61. doi: 10.1002/wrna.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jackman JE, Alfonzo JD. Transfer RNA modifications: nature's combinatorial chemistry playground. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Rna. 2013;4:35–48. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Halgren TA, Damm W. Polarizable force fields. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2001;11:236–242. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Thole BT. Molecular Polarizabilities Calculated with a Modified Dipole Interaction. Chemical Physics. 1981;59:341–350. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Torres AG, Batlle E, de Pouplana LR. Role of tRNA modifications in human diseases. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2014;20:306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yacoubi B. El, Bailly M, de Crecy-Lagard V. Biosynthesis and Function of Posttranscriptional Modifications of Transfer RNAs. Annual Review of Genetics. 2012;46:69–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Helm M. Post-transcriptional nucleotide modification and alternative folding of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:721–733. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Agris PF. Bringing order to translation: the contributions of transfer RNA anticodon-domain modifications. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:629–635. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nobles KN, Yarian CS, Liu G, Guenther RH, Agris PF. Highly conserved modified nucleosides influence Mg2+-dependent tRNA folding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4751–4760. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kim HD, Puglisi JD, Chu S. Fluctuations of transfer RNAs between classical and hybrid states. Biophysical Journal. 2007;93:3575–3582. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.109884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Draper DE. RNA folding: thermodynamic and molecular descriptions of the roles of ions. Biophys J. 2008;95:5489–5495. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.131813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Agris PF, Vendeix FA, Graham WD. tRNA's wobble decoding of the genome: 40 years of modification. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nasvall SJ, Chen P, Bjork GR. The wobble hypothesis revisited: Uridine-5-oxyacetic acid is critical for reading of G-ending codons. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 2007;13:2151–2164. doi: 10.1261/rna.731007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nasvall SJ, Chen P, Bjork GR. The modified wobble nucleoside uridine-5-oxyacetic acid in tRNA(cmo5UGG)(Pro) promotes reading of all four proline codons in vivo. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 2004;10:1662–1673. doi: 10.1261/rna.7106404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Stuart JW, Koshlap KM, Guenther R, Agris PF. Naturally-occurring modification restricts the anticodon domain conformational space of tRNA(Phe) Journal of Molecular Biology. 2003;334:901–918. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dalluge JJ, Hamamoto T, Horikoshi K, Morita RY, Stetter KO, McCloskey JA. Posttranscriptional modification of tRNA in psychrophilic bacteria. Journal of Bacteriology. 1997;179:1918–1923. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1918-1923.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Basavappa R, Sigler PB. The 3 A crystal structure of yeast initiator tRNA: functional implications in initiator/elongator discrimination. EMBO J. 1991;10:3105–3111. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07864.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shi H, Moore PB. The crystal structure of yeast phenylalanine tRNA at 1.93 A resolution: a classic structure revisited. RNA. 2000;6:1091–1105. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Weixlbaumer A, Murphy FV, Dziergowska A, Malkiewicz A, Vendeix FAP, Agris PF, Ramakrishnan V. Mechanism for expanding the decoding capacity of transfer RNAs by modification of uridines. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2007;14:498–502. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Benas P, Bec G, Keith G, Marquet R, Ehresmann C, Ehresmann B, Dumas P. The crystal structure of HIV reverse-transcription primer tRNA(Lys,3) shows a canonical anticodon loop. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 2000;6:1347–1355. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Brooks BR, Brooks CL, 3rd, Mackerell AD, Jr., Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, Won Y, Archontis G, Bartels C, Boresch S, Caflisch A, Caves L, Cui Q, Dinner AR, Feig M, Fischer S, Gao J, Hodoscek M, Im W, Kuczera K, Lazaridis T, Ma J, Ovchinnikov V, Paci E, Pastor RW, Post CB, Pu JZ, Schaefer M, Tidor B, Venable RM, Woodcock HL, Wu X, Yang W, York DM, Karplus M. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Karplus M, Lavery R. Significance of Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Life Sciences. Israel Journal of Chemistry. 2014;54:1042–1051. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Karplus M. Development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems: from H+H(2) to biomolecules (Nobel Lecture) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:9992–10005. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cheatham TE, Case DA. Twenty-five years of nucleic acid simulations. Biopolymers. 2013;99:969–977. doi: 10.1002/bip.22331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].McCrate NE, Varner ME, Kim KI, Nagan MC. Molecular dynamics simulations of human tRNA (Lys,3)(UUU) : the role of modified bases in mRNA recognition. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:5361–5368. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Allner O, Nilsson L. Nucleotide modifications and tRNA anticodon-mRNA codon interactions on the ribosome. RNA. 2011;17:2177–2188. doi: 10.1261/rna.029231.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Witts RN, Hopson EC, Koballa DE, Van Boening TA, Hopkins NH, Patterson EV, Nagan MC. Backbone-Base Interactions Critical to Quantum Stabilization of Transfer RNA Anticodon Structure. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2013;117:7489–7497. doi: 10.1021/jp400084p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhang XJ, Walker RC, Phizicky EM, Mathews DH. Influence of Sequence and Covalent Modifications on Yeast tRNA Dynamics. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2014;10:3473–3483. doi: 10.1021/ct500107y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Xu Y, Vanommeslaeghe K, Aleksandrov A, MacKerell AD, Jr., Nilsson L. Additive CHARMM force field for naturally occurring modified ribonucleotides. J Comput Chem. 2016;37:896–912. doi: 10.1002/jcc.24307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Barraud P, Schmitt E, Mechulam Y, Dardel F, Tisne C. A unique conformation of the anticodon stem-loop is associated with the capacity of tRNAfMet to initiate protein synthesis. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36:4894–4901. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Allner O, Nilsson L, Villa A. Magnesium Ion-Water Coordination and Exchange in Biomolecular Simulations. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2012;8:1493–1502. doi: 10.1021/ct3000734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Friedrichs MS, Eastman P, Vaidyanathan V, Houston M, Legrand S, Beberg AL, Ensign DL, Bruns CM, Pande VS. Accelerating Molecular Dynamic Simulation on Graphics Processing Units. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2009;30:864–872. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Foloppe N, MacKerell AD. All-atom empirical force field for nucleic acids: I. Parameter optimization based on small molecule and condensed phase macromolecular target data. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2000;21:86–104. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Denning EJ, Priyakumar UD, Nilsson L, Mackerell AD. Impact of 2'-Hydroxyl Sampling on the Conformational Properties of RNA: Update of the CHARMM All-Atom Additive Force Field for RNA. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2011;32:1929–1943. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Vanommeslaeghe K, Hatcher E, Acharya C, Kundu S, Zhong S, Shim J, Darian E, Guvench O, Lopes P, Vorobyov I, Mackerell AD., Jr. CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:671–690. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Yu WB, He XB, Vanommeslaeghe K, MacKerell AD. Extension of the CHARMM general force field to sulfonyl-containing compounds and its utility in biomolecular simulations. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2012;33:2451–2468. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of Simple Potential Functions for Simulating Liquid Water. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle Mesh Ewald - an N.Log(N) Method for Ewald Sums in Large Systems. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Steinbach PJ, Brooks BR. New Spherical-Cutoff Methods for Long-Range Forces in Macromolecular Simulation. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 1994;15:667–683. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. Numerical-Integration of Cartesian Equations of Motion of a System with Constraints - Molecular-Dynamics of N-Alkanes. Journal of Computational Physics. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Altona C, Sundaralingam M. Conformational analysis of the sugar ring in nucleosides and nucleotides. A new description using the concept of pseudorotation. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:8205–8212. doi: 10.1021/ja00778a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Valle M, Sengupta J, Swami NK, Grassucci RA, Burkhardt N, Nierhaus KH, Agrawal RK, Frank J. Cryo-EM reveals an active role for aminoacyl-tRNA in the accommodation process. EMBO J. 2002;21:3557–3567. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ashraf SS, Sochacka E, Cain R, Guenther R, Malkiewicz A, Agris PF. Single atom modification (O - > S) of tRNA confers ribosome binding. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 1999;5:188–194. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299981529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ashraf SS, Guenther RH, Ansari G, Malkiewicz A, Sochacka E, Agris PF. Role of modified nucleosides of yeast tRNA(Phe) in ribosomal binding. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2000;33:241–252. doi: 10.1385/cbb:33:3:241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bajji AC, Davis DR. Synthesis and biophysical characterization of tRNA(LyS,3) anticodon stem-loop RNAs containing the mcm(5)s(2)U nucleoside. Organic Letters. 2000;2:3865–3868. doi: 10.1021/ol006605h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Rodriguez-Hernandez A, Spears JL, Gaston KW, Limbach PA, Gamper H, Hou YM, Kaiser R, Agris PF, Perona JJ. Structural and Mechanistic Basis for Enhanced Translational Efficiency by 2-Thiouridine at the tRNA Anticodon Wobble Position. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2013;425:3888–3906. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Larsen AT, Fahrenbach AC, Sheng J, Pian JL, Szostak JW. Thermodynamic insights into 2-thiouridine-enhanced RNA hybridization. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43:7675–7687. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Agris PF, Sierzputowskagracz H, Smith W, Malkiewicz A, Sochacka E, Nawrot B. Thiolation of Uridine Carbon-2 Restricts the Motional Dynamics of the Transfer-Rna Wobble Position Nucleoside. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1992;114:2652–2656. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Schmidt PG, Sierzputowskagracz H, Agris PF. Internal Motions in Yeast Phenylalanine Transfer-Rna from C-13 Nmr Relaxation Rates of Modified Base Methyl-Groups - a Model-Free Approach. Biochemistry. 1987;26:8529–8534. doi: 10.1021/bi00400a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Stuart JW, Gdaniec Z, Guenther R, Marszalek M, Sochacka E, Malkiewicz A, Agris PF. Functional anticodon architecture of human tRNALys3 includes disruption of intraloop hydrogen bonding by the naturally occurring amino acid modification, t6A. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13396–13404. doi: 10.1021/bi0013039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Yarian C, Townsend H, Czestkowski W, Sochacka E, Malkiewicz AJ, Guenther R, Miskiewicz A, Agris PF. Accurate translation of the genetic code depends on tRNA modified nucleosides. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:16391–16395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Lescrinier E, Nauwelaerts K, Zanier K, Poesen K, Sattler M, Herdewijn P. The naturally occurring N6-threonyl adenine in anticodon loop of Schizosaccharomyces pombe tRNAi causes formation of a unique U-turn motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2878–2886. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Durant PC, Bajji AC, Sundaram M, Kumar RK, Davis DR. Structural effects of hypermodified nucleosides in the Escherichia coli and human tRNA(Lys) anticodon loop: The effect of nucleosides s(2)U, mcm(5)U, mcm(5)s(2)U, mnm(5)s(2)U, t(6)A, and ms(2)t(6)A. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8078–8089. doi: 10.1021/bi050343f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Murphy F.V.t., Ramakrishnan V, Malkiewicz A, Agris PF. The role of modifications in codon discrimination by tRNA(Lys)UUU. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1186–1191. doi: 10.1038/nsmb861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Vendeix FA, Murphy F.V.t., Cantara WA, Leszczynska G, Gustilo EM, Sproat B, Malkiewicz A, Agris PF. Human tRNA(Lys3)(UUU) is pre-structured by natural modifications for cognate and wobble codon binding through keto-enol tautomerism. J Mol Biol. 2012;416:467–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Auffinger P, Westhof E. Singly and bifurcated hydrogen-bonded base-pairs in tRNA anticodon hairpins and ribozymes. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1999;292:467–483. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Schmitt E, Panvert M, Blanquet S, Mechulam Y. Crystal structure of methionyl-tRNAfMet transformylase complexed with the initiator formyl-methionyl-tRNAfMet. EMBO J. 1998;17:6819–6826. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.6819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Ashraf SS, Ansari G, Guenther R, Sochacka E, Malkiewicz A, Agris PF. The uridine in "U-turn": Contributions to tRNA-ribosomal binding. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 1999;5:503–511. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299981931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Dalluge JJ, Hashizume T, Sopchik AE, McCloskey JA, Davis DR. Conformational flexibility in RNA: The role of dihydrouridine. Nucleic Acids Research. 1996;24:1073–1079. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.6.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Sipa K, Sochacka E, Kazmierczak-Baranska J, Maszewska M, Janicka M, Nowak G, Nawrot B. Effect of base modifications on structure, thermodynamic stability, and gene silencing activity of short interfering RNA. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 2007;13:1301–1316. doi: 10.1261/rna.538907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Dyubankova N, Sochacka E, Kraszewska K, Nawrot B, Herdewijn P, Lescrinier E. Contribution of dihydrouridine in folding of the D-arm in tRNA. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 2015;13:4960–4966. doi: 10.1039/c5ob00164a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Byrne RT, Jenkins HT, Peters DT, Whelan F, Stowell J, Aziz N, Kasatsky P, Rodnina MV, Koonin EV, Konevega AL, Antson AA. Major reorientation of tRNA substrates defines specificity of dihydrouridine synthases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:6033–6037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500161112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Davis DR. Stabilization of RNA stacking by pseudouridine. Nucleic Acids Research. 1995;23:5020–5026. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.24.5020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Davis DR, Veltri CA, Nielsen L. An RNA model system for investigation of pseudouridine stabilization of the codon-anticodon interaction in tRNALys, tRNAHis and tRNATyr. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 1998;15:1121–1132. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1998.10509006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Durant PC, Davis DR. Stabilization of the anticodon stem-loop of tRNA(LyS,3) by an A(+)-C base-pair and by pseudouridine. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1999;285:115–131. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Kierzek E, Malgowska M, Lisowiec J, Turner DH, Gdaniec Z, Kierzek R. The contribution of pseudouridine to stabilities and structure of RNAs. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;42:3492–3501. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Nickels JD, Curtis JE, O'Neill H, Sokolov AP. Role of methyl groups in dynamics and evolution of biomolecules. Journal of Biological Physics. 2012;38:497–505. doi: 10.1007/s10867-012-9268-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Hori H, Kubota S, Watanabe K, Kim JM, Ogasawara T, Sawasaki T, Endo Y. Aquifex aeolicus tRNA (Gm18) methyltransferase has unique substrate specificity - tRNA recognition mechanism of the enzyme. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:25081–25090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Awai T, Kimura S, Tomikawa C, Ochi A, Ihsanawati, Bessho Y, Yokoyama S, Ohno S, Nishikawa K, Yokogawa T, Suzuki T, Hori H. Aquifex aeolicus tRNA (N-2, N-2-Guanine)-dimethyltransferase (Trm1) Catalyzes Transfer of Methyl Groups Not Only to Guanine 26 but Also to Guanine 27 in tRNA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:20467–20478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.020024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Finer-Moore J, Czudnochowski N, O'Connell JD, Wang AL, Stroud RM. Crystal Structure of the Human tRNA m(1) A58 Methyltransferase-tRNA(3)(LYs) Complex: Refolding of Substrate tRNA Allows Access to the Methylation Target. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2015;427:3862–3876. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Urbonavicius J, Armengaud J, Grosjean H. Identity elements required for enzymatic formation of N-2, N-2-dimethylguanosine from N-2-monomethylated derivative and its possible role in avoiding alternative conformations in archaeal tRNA. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2006;357:387–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Satoh A, Takai K, Ouchi R, Yokoyama S, Takaku H. Effects of anticodon 2 '-O-methylations on tRNA codon recognition in an Escherichia coli cell-free translation. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 2000;6:680–686. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Chawla M, Oliva R, Bujnicki JM, Cavallo L. An atlas of RNA base pairs involving modified nucleobases with optimal geometries and accurate energies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Konevega AL, Soboleva NG, Makhno VI, Semenkov YP, Wintermeyer W, Rodina MV, Katunin VI. Purine bases at position 37 of tRNA stabilize codon-anticodon interaction in the ribosomal A site by stacking and Mg2+-dependent interactions. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 2004;10:90–101. doi: 10.1261/rna.5142404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Sussman JL, Holbrook SR, Warrant RW, Church GM, Kim SH. Crystal-Structure of Yeast Phenylalanine Transfer-Rna .1. Crystallographic Refinement. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1978;123:607–630. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Westhof E, Dumas P, Moras D. Restrained Refinement of 2 Crystalline Forms of Yeast Aspartic-Acid and Phenylalanine Transfer-Rna Crystals. Acta Crystallographica Section A. 1988;44:112–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.