Abstract

Context:

The vasoactive intestinal peptide-secreting neuroendocrine tumor (VIPoma) is a very rare pancreatic tumor. We report the first case of a patient with VIPoma that co-secreted dopamine and had pulmonary emboli.

Case Description:

A 67-year-old woman presented with 2 months of watery diarrhea, severe generalized weakness,6.8 kg of weight loss, a facial rash, and hypokalemia. Colonoscopy did not reveal the cause of the chronic diarrhea. Initial biochemical testing showed markedly elevated serum vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pancreatic polypeptide. Computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a 5.4-cm distal pancreatic mass. Octreoscan showed an intense uptake in the area of the pancreatic mass. Incidental pulmonary emboli were found and treated. Additional biochemical testing revealed a markedly elevated urinary dopamine level. The patient received preoperative α-blockade and octreotide. She underwent a successful laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. Postoperative urinary dopamine and pancreatic polypeptide were within normal limits. Serum VIP decreased by half but remained elevated. Pathology confirmed a grade 1 pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor without lymph node metastasis. The patient's symptoms resolved and no longer required octreotide. Metastatic workup including computed tomography, F18-fluorodeoxglucose positron emission tomography, and Ga68-DOTATATE scans were negative during 4 years of follow-up.

Conclusions:

VIPoma is a rare subtype of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor that can secrete dopamine and can be associated with thromboembolism.

We reported a unique case of a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor and pulmonary emboli with histologic and biochemical evidence of vasoactive intestinal peptide and dopamine secretion.

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are rare neoplasms of the pancreas. The annual incidence in the United States was estimated to be three to five cases per 100 000 individuals (1). Although > 85% of PNETs are nonfunctioning, patients with functioning PNETs typically present with clinical syndromes associated with excessive hormonal secretion. The vasoactive intestinal peptide-secreting neuroendocrine tumor (VIPoma), also known as Verner-Morrison syndrome, is a very rare tumor with an annual incidence of one in 10 million individuals (2). However, none of the previously reported cases of VIPoma exhibited catecholamine co-secretion. We report a unique case of a PNET that secreted both vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and dopamine and highlight a unique clinical presentation as well as a thromboembolic event.

Case Presentation

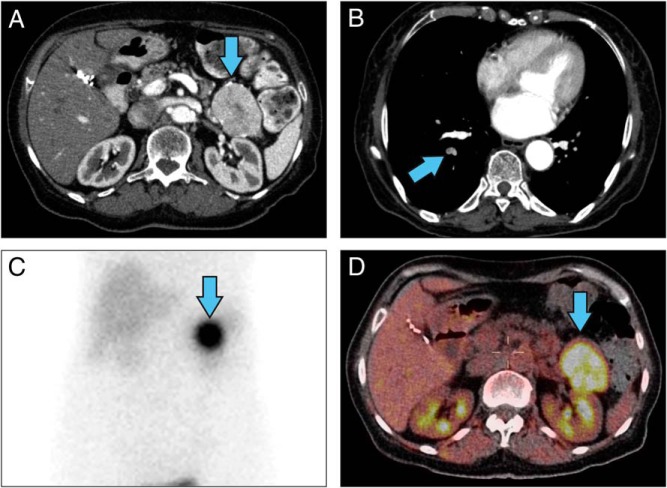

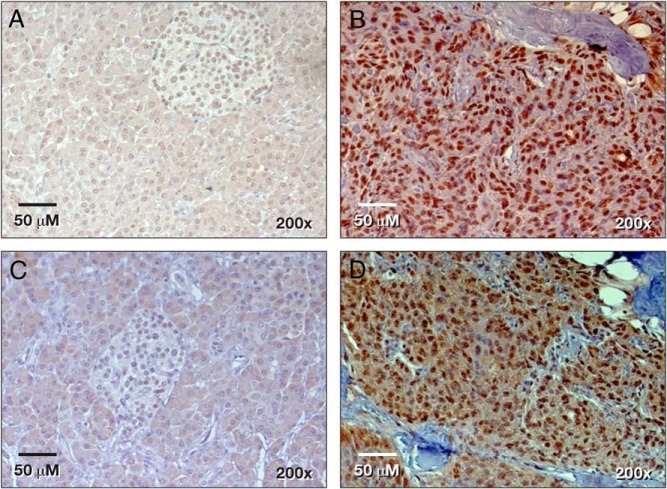

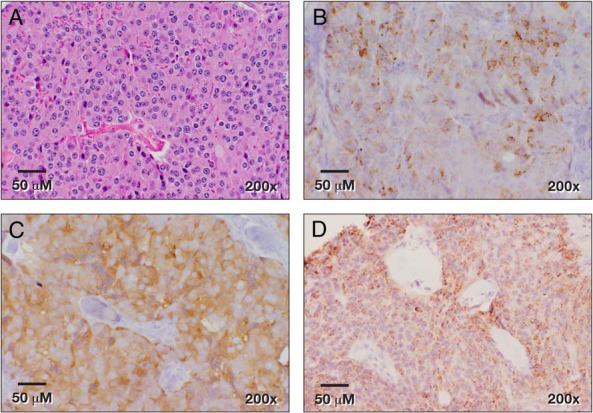

A 67-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypothyroidism, and gastroesophageal reflux disease presented with watery diarrhea several times a day for 2 months, severe generalized weakness, and 6.8 kg of weight loss. She was initially admitted and treated for dehydration and hypokalemia. A colonoscopy showed an ulcerative lesion in the ascending colon and colitis. The patient came to the National Institutes of Health because a computed tomography (CT) scan of her abdomen demonstrated a 5.4 × 3.8-cm solid mass with a focal calcification at the tail of the pancreas (Figure 1A), and her serum VIP level was markedly elevated. Octreotide treatment (50 μg sc daily) dramatically improved her diarrhea. Her social and family histories were unremarkable. The patient presented without distress and had normal vital signs and oxygenation on room air. She had a facial erythematous maculopapular rash. She had no palpable abdominal mass or organomegaly. Her significant laboratory values included low hemoglobin at 10.2 g/dL (11.2–15.7 g/dL), elevated VIP at 3750 pg/mL (<75 pg/mL), pancreatic polypeptide at 106 000 pg/mL (<312 pg/mL), and 24-hour urine dopamine at 1592 μg/24 hours (65–400 μg/24 hours). Urinary norepinephrine, epinephrine, and total metanephrines were within normal limits. In addition to a solid mass in the tail of the pancreas, we found incidental pulmonary emboli in the right lower-lobe arteries (Figure 1B), which were treated with enoxaparin. A venous duplex study of the lower extremities revealed no thrombus. An octreoscan showed intense uptake in the area of the pancreatic tail mass (Figure 1C), which had increased uptake on F18-fluorodeoxglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT with a standardized uptake value of 7.9 (Figure 1D). Because of the elevated dopamine level, phenoxybenzamine was given preoperatively. The patient provided an informed written consent for surgery and research. She underwent an uncomplicated laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy. An intraoperative ultrasound of the liver and pancreas revealed no additional lesions. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 5 with a drain for a self-limited, grade 1 pancreatic fistula. Pathology showed a 5.5-cm grade 1 PNET with a 1% Ki67 index and negative margins (Figure 2A). All 13 of her lymph nodes were negative for metastasis. The tumor cells stained positive for synaptophysin, chromogranin, pancreatic polypeptide, VIP, and DOPA-decarboxylase (Figure 2, B–D, and Figure 3, B and D) and stained negative for glucagon, somatostatin, and insulin. Her pancreatic polypeptide and urine dopamine levels were normalized postoperatively. The patient's VIP level decreased but remained elevated at 1510 pg/mL (<75 pg/mL) and did not increase significantly over 4 years of follow-up. Annual radiographic surveillance with octreoscans, F18-FDG PET/CT scans, Ga-68 DOTATATE PET/CT scans, and contrast-enhanced CT scans showed that the patient had no evidence of disease during 4 years of follow-up after surgery. The patient remained asymptomatic without any treatment. Genetic testing for MEN1, VHL, and NF1 germline mutations was negative.

Figure 1.

Radiographic imaging of a patient with VIPoma. A, Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen showed pancreatic tail mass (blue arrow). B, A pulmonary CT angiography showed right segmental pulmonary artery-filling defects. C, Octreoscan. D, F18-FDG PET/CT scan showed an intense uptake in the pancreatic tail mass.

Figure 2.

Histology of PNET secreting VIP and dopamine. A, Hematoxylin and eosin staining; B, synaptophysin; C, chromogranin; and D, pancreatic polypeptide immunohistochemistry.

Figure 3.

VIP expression in the adjacent normal pancreas (A) and in the PNET (B). DOPA-decarboxylase expression in the adjacent normal pancreas (C) and in the PNET (D).

Discussion

Neuroendocrine tumors are a heterogeneous group of tumors originating from various types of specialized cells that express markers for neurons and frequently secrete peptides or amines, resulting in diverse clinical presentations and biological behaviors. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of a VIPoma co-secreting dopamine. We found strong nuclear expression of VIP and DOPA-decarboxylase in the patient's tumor sample. Few reports of patients with VIPoma demonstrated that VIP can express in nuclei and cytoplasm (3, 4). Elevated catecholamines and metabolites have been reported in 8% (n = 9 of 115) of patients with neuroendocrine tumors (5). Immunohistochemistry suggested that neuroendocrine cells can express tyrosine hydroxylase and DOPA-decarboxylase, which convert tyrosine to L-DOPA and L-dopa to dopamine, respectively (6). In addition to the typical symptoms of profuse watery diarrhea, hypokalemia, and dehydration universally found in patients with VIPomas (2), our patient had incidentally found pulmonary emboli. Thromboembolisms in patients with VIPomas have rarely been reported. Interestingly, the first case of VIPoma was described in 1957 in a patient who presented with severe diarrhea, hypokalemia, and a pancreatic tail mass with liver metastasis. Her clinical course was complicated by popliteal artery thrombosis that required leg amputation (7). The mean age of patients at presentation of VIPomas is between 50 and 60 years (2, 8). The tumor location in our patient was consistent with previous reports demonstrating that 72% of VIPomas were in the body or tail of the pancreas. However, unlike two-thirds of patients with VIPomas who present with metastatic disease (2), there was no radiographic evidence of metastasis at the time of diagnosis and during follow-up. It is possible that our patient has microscopic metastasis because her VIP levels remain elevated. However, occult VIPoma has been reported in a patient with a clinical syndrome consistent with VIPoma, and primary and metastatic lesions were discovered 3 years later (9). This suggests that the clinical course of VIPoma can be indolent, similar to other PNETs. Because PNETs can secrete multiple hormones and peptides, VIPomas have been reported to secrete several other hormones such as pancreatic polypeptide, calcitonin, gastrin, neurotensin, gastric inhibitory peptide, serotonin, glucagon, insulin, and somatostatin (10). To our knowledge, our patient is the first whose VIPoma secreted dopamine. There have been reports of pheochromocytoma that secreted dopamine and VIP (11, 12). This suggests that neuroendocrine cells can secrete both catecholamines and pancreatic peptides. Because most patients with VIPomas have tumors larger than 3 cm, a contrast-enhanced CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging has > 80% sensitivity in detecting the primary and metastatic sites (2, 13). Functional imaging studies, such as octreoscan and Ga-68 DOTATATE PET/CT, can be useful in detecting primary tumors and metastasis because most VIPomas express somatostatin receptors. F18-FDG PET/CT can be more sensitive than somatostatin receptor imaging in patients with poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. However, it is common for well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors to be F18-FDG PET/CT avid (14). Initial treatment of patients with VIPomas includes hydration and correction of electrolyte abnormalities. A somatostatin analog, such as octreotide, can be used to control symptoms. Surgical resection with lymphadenectomy is the treatment of choice in patients with localized or regionalized disease. U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments for progressive or advanced PNETs include sunitinib and everolimus. Various modalities, such as chemoembolization and radiofrequency ablation, have been used to control the progression of liver metastasis. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy has emerged as a promising modality in patients with avid tumors, as determined by Ga-68 DOTA peptide PET/CT imaging. The 5-year survival for patients with localized and metastatic pancreatic VIPomas is 94% and 60%, respectively (8).

Conclusions

VIPoma is a rare subtype of PNETs that can secrete dopamine and can be associated with thromboembolism.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

- CT

- computed tomography

- FDG

- fluorodeoxglucose

- PET

- positron emission tomography

- PNET

- pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor

- VIP

- vasoactive intestinal peptide

- VIPoma

- VIP-secreting neuroendocrine tumor.

References

- 1. Halfdanarson TR, Rubin J, Farnell MB, Grant CS, Petersen GM. Pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: epidemiology and prognosis of pancreatic endocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:409–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ghaferi AA, Chojnacki KA, Long WD, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ. Pancreatic VIPomas: subject review and one institutional experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:382–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bani Sacchi T, Bani D, Biliotti G. Are pancreatic VIPomas paraneuron neoplasms? A clue to the neuroectodermal origin of these tumors. Pancreas. 1992;7:87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen YF, Liu TH, Chen SP, et al. Watery diarrhea syndrome caused by multihormonal malignant pancreatic islet cell tumor secreting somatostatin, vasoactive intestinal peptide, serotonin, and prostaglandin E–a clinicopathological, biochemical, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study. Pancreas. 1986;1:80–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ciofu A, Baudin E, Chanson P, et al. Catecholamine production in patients with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Eur J Endocrinol. 1999;140:434–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goedert M, Otten U, Suda K, et al. Dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin production by an intestinal carcinoid tumor. Cancer. 1980;45:104–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Priest WM, Alexander MK. Isletcell tumour of the pancreas with peptic ulceration, diarrhoea, and hypokalaemia. Lancet. 1957;273:1145–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Soga J, Yakuwa Y. Vipoma/diarrheogenic syndrome: a statistical evaluation of 241 reported cases. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 1998;17:389–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brunani A, Crespi C, De Martin M, Dubini A, Piolini M, Cavagnini F. Four year treatment with a long acting somatostatin analogue in a patient with Verner-Morrison syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 1991;14:685–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Perry RR, Vinik AI. Clinical review 72: diagnosis and management of functioning islet cell tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:2273–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smith SL, Slappy AL, Fox TP, Scolapio JS. Pheochromocytoma producing vasoactive intestinal peptide. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ikuta S, Yasui C, Kawanaka M, et al. Watery diarrhea, hypokalemia and achlorhydria syndrome due to an adrenal pheochromocytoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4649–4652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. King CM, Reznek RH, Dacie JE, Wass JA. Imaging islet cell tumours. Clin Radiol. 1994;49:295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Squires MH, 3rd, Volkan Adsay N, Schuster DM, et al. Octreoscan versus FDG-PET for neuroendocrine tumor staging: a biological approach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2295–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]