Abstract

Background

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (αIIb/β3) is involved in platelet adhesion, and triggers a series of intracellular signaling cascades, leading to platelet shape change, granule secretion, and clot retraction. In this study, we evaluated the effect of ginsenoside Ro (G-Ro) on the binding of fibrinogen to αIIb/β3.

Methods

We investigated the effect of G-Ro on regulation of signaling molecules affecting the binding of fibrinogen to αIIb/β3, and its final reaction, clot retraction.

Results

We found that G-Ro dose-dependently inhibited thrombin-induced platelet aggregation and attenuated the binding of fibrinogen to αIIb/β3 by phosphorylating cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-dependently vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP; Ser157). In addition, G-Ro strongly abrogated the clot retraction reflecting the intensification of thrombus.

Conclusion

We demonstrate that G-Ro is a beneficial novel compound inhibiting αIIb/β3-mediated fibrinogen binding, and may prevent platelet aggregation-mediated thrombotic disease.

Keywords: cAMP, clot retraction, ginsenoside Ro, fibrinogen binding, VASP (Ser157)

1. Introduction

Activation of platelets by various agonists (i.e., adenosine diphosphate, collagen, thrombin) causes shape change, granule secretion, and platelet aggregation. These signaling events are mediated by the activation of integrins such as glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (αIIb/β3). Activated αIIb/β3 interacts with its ligands (i.e., fibrinogen, fibronectin), then causes Ca2+ mobilization, granule secretion, and clot retraction [1], [2], [3], and subsequently augments the formation of thrombus.

Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) in platelets is associated with actin filament dynamics and focal adhesions, but its phosphorylated-forms (Ser157, Ser239) weaken the affinity of VASP for actin filaments to block the binding of adhesive proteins to αIIb/β3 [4], [5]. Accordingly, phosphorylation of VASP could be used to appreciate the binding of adhesive proteins to αIIb/β3, and contribute to estimating the antithrombotic effect of a certain compound. For instance, antiplatelet compounds such as p-terphenyl curtisian E and quercetin lead to VASP phosphorylation [6], [7]. In addition, abciximab, eptifibatide, tirofiban, and lamifiban are known to inhibit the activation of αIIb/β3 [8], [9].

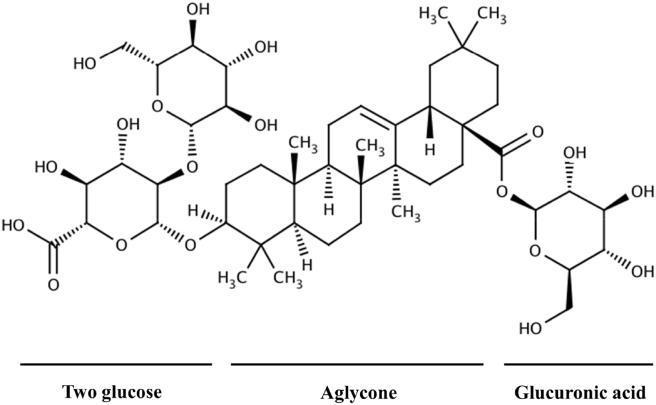

Ginseng, the root of Panax ginseng Meyer, has been used frequently in traditional Oriental medicine. Ginsenoside Ro (G-Ro; Fig. 1), an oleanane-type saponin, in P. ginseng Meyer [10], [11], is known to inhibit fibrin formation [12], [13], and has no inhibitory effect on collagen-elevated platelet aggregation [14]. Until now, there has been no report on the antiplatelet mechanism of G-Ro. In this study, we found that G-Ro stimulates VASP (Ser157) phosphorylation in a cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent manner, which attenuates the binding of fibrinogen to αIIb/β3, and clot retraction in thrombin-activated human platelets.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of ginsenoside Ro. Ginsenoside Ro (G-Ro), an oleanane-type saponin, is contained in Panax ginseng Meyer [10], [11], and is composed of oleanolic acid as aglycone, and two glucose and one glucuronic acid as sugar component [10].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

G-Ro was obtained from Ambo Institute (Daejon, Korea). Thrombin was obtained from Chrono-Log Corporation (Havertown, PA, USA). Anti-VASP, anti-phosphor-VASP (Ser157), anti-phosphor-VASP (Ser239), anti-rabbit IgG-HRP-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (HRP), and lysis buffer were purchased from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA, USA). The αIIb/β3 inhibitor eptifibatide, GR 144053, and anti-β-actin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Polyvinylidene difluoride membrane was purchased from GE Healthcare (Piseataway, NJ, USA). Enhanced chemiluminescence solution was purchased from GE Healthcare (Chalfont St. Giles, UK). cAMP and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) enzyme immunoassay kits were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). An A-kinase inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS, an A-kinase activator 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-cAMP (pCPT-cAMP), and a G-kinase activator 8-Br-cGMP were purchased from Sigma Chemical Corporation (St. Louis, MO, USA). Fibrinogen Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate was obtained from Invitrogen Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA).

2.2. Preparation of washed human platelets

Human platelet-rich plasma with acid-citrate-dextrose solution (0.8% citric acid, 2.2% sodium citrate, 2.45% glucose) was supplied from Korean Red Cross Blood Center (Changwon, Korea). To remove red blood cells and white blood cells, it was centrifuged for 10 min at 250g and 10 min at 1,300g. The platelets were washed twice using washing buffer (138mM NaCl, 2.7mM KCl, 12mM NaHCO3, 0.36mM NaH2PO4, 5.5mM glucose, and 1mM Na2EDTA, pH 6.5), then resuspended in suspension buffer (138mM NaCl, 2.7mM KCl, 12mM NaHCO3, 0.36mM NaH2PO4, 0.49mM MgCl2, 5.5mM glucose, 0.25% gelatin, pH 6.9) to a final concentration of 5 × 108/mL. All of the above procedures were performed at 25°C to maintain platelet activity. Approval (PIRB12-072) for these experiments was received from the National Institute for Bioethics Policy Public Institutional Review Board (Seoul, Korea).

2.3. Determination of platelet aggregation

Washed human platelets (108/mL) were preincubated with or without G-Ro in the reaction system containing 2mM of CaCl2 for 3 min at 37°C, then stimulated with thrombin (0.05 U/mL). The aggregation was performed for 5 min using an aggregometer (Chrono-Log Corporation, Havertown, PA, USA) at a constant stirring speed of 1,000 rpm. Each aggregation rate was determined as an increase in light transmission. G-Ro was dissolved in platelet suspension buffer (pH 6.9), and suspension buffer was used as the reference (transmission 0)

2.4. Western blot for analysis of VASP-phosphorylation

The platelet aggregation was terminated by adding an equal volume (250 μL) of lysis buffer (20mM Tris-HCl, 150mM NaCl, 1mM Na2EDTA, 1mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1mM serine/threonine phosphatase inhibitor β-glycerophosphate, 1mM ATPase, alkaline, and acid phosphatase, and protein phosphotyrosine phosphatase inhibitor Na3VO4, 1 μg/mL serine and cysteine protease inhibitor leupeptin, and 1mM serine protease and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, pH 7.5). Protein contents were measured using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). Proteins (15 μg) were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (6%, 1.5 mm), then polyvinylidene difluoride membrane was used for protein transfer from the gel. The dilutions for anti-VASP, anti-phosphor-VASP (Ser157), anti-phosphor-VASP (Ser239), and anti-rabbit IgG-HRP were 1:1,000, 1:1,000, 1:1,000, and 1:10,000, respectively. The membranes were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence solution. The degrees of protein phosphorylation were analyzed using the Quantity One, version 4.5 (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.5. Determination of fibrinogen binding to αIIb/β3

The platelet aggregation was conducted in the presence of Alexa Flour 488-human fibrinogen (30 μg/mL) for 5 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.5% paraformaldehyde in cold phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4), and the aforementioned procedures were implemented under dark conditions. The assay of fibrinogen binding was carried out using flow cytometry (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), and its degree was determined with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

2.6. Assay of platelet-mediated fibrin clot retraction

Human platelet-rich plasma, 250 μL, was preincubated with or without G-Ro (300μM) for 10 min at 37°C, and incubated with thrombin (0.05 U/mL) for 10 min and 20 min at 37°C. Photographs of the fibrin clot were taken by a digital camera, and its area (at 20 min) was measured by NIH Image J Software (version 1.46, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). Percentage of clot retraction was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

2.7. Measurement of cAMP and cGMP

After platelet aggregation, 80% ice cold ethanol was added to terminate the reaction, and cAMP and cGMP were extracted three times with 80% ice cold ethanol. The extracts tubes were dried by nitrogen gas, and subsequently dissolved with assay buffer (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The level of cAMP and cGMP was determined with Synergy HT Multi-Model Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Winoosku, VT, USA).

2.8. Statistical analysis

The experimental results are indicated as the mean ± standard deviation accompanied by the number of observations. Data were determined by analysis of variance. If this analysis showed significant differences among the group means, then each group was compared by the Newman-Keuls method. Statistical analysis was carried out according to the SPSS 21.0.0.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A p value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

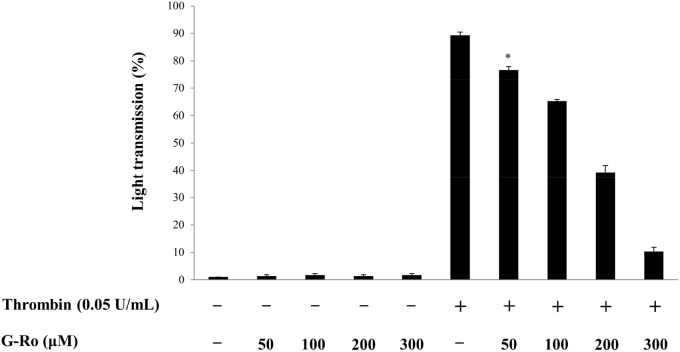

3.1. Effects of G-Ro on thrombin-induced human platelet aggregation

Because 0.05 U/mL of thrombin maximally aggregated human platelets [15], this concentration was used to investigate the antiplatelet effect of G-Ro (Fig. 1). In unstimulated platelets, the light transmission in response to various concentrations of G-Ro (50μM, 100μM, 200μM, 300μM) was 1.3 ± 0.6% (at 50μM of G-Ro), 1.7 ± 0.6% (at 100μM of G-Ro), 1.3 ± 0.6% (at 200μM of G-Ro), and 1.7 ± 0.6% (at 300μM of G-Ro), which were not significantly different from that (1.0 ± 0.0%) in resting platelets without G-Ro (Fig. 2). Thrombin increased light transmission and the aggregation rate was 90.7 ± 1.2% (Fig. 2). However, G-Ro dose-dependently (50μM, 100μM, 200μM, 300μM) reduced thrombin-elevated light transmission, meaning G-Ro inhibits thrombin-induced platelet aggregation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effects of ginsenoside Ro (G-Ro) on thrombin-induced human platelet aggregation. Measurement of platelet aggregation was carried out as described in the “Materials and methods” section. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4). * p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets.

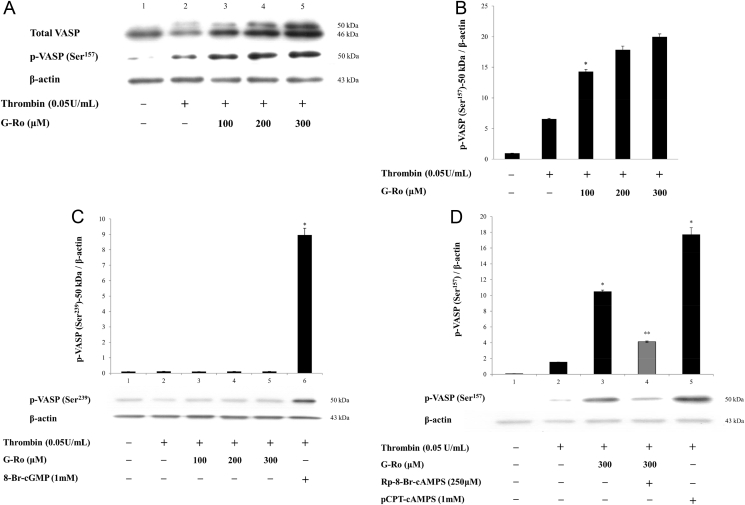

3.2. Effects of G-Ro on VASP phosphorylation

In intact platelets, 46 kDa dephosphoprotein only of VASP was observed (Fig. 3A, Lane 1). Thrombin weakly increased the phosphorylation of VASP (Ser157) at 50 kDa phosphoprotein of VASP (Fig. 3A, Lane 2), and the ratio of p-VASP (Ser157) to β-actin (Fig. 3B). This means that 46 kDa dephosphoprotein of VASP (46 kDa + 50 kDa) was weakly shifted to 50 kDa phosphoprotein by thrombin, and thrombin is involved in a feedback inhibition by elevating p-VASP (Ser157, Ser239) [16]. Because G-Ro dose (100, 200, 300 μM)-dependently inhibited up to 26.9 ± 0.6% (by 100 μM G-Ro), 56.0 ± 2.8% (by 200 μM G-Ro), and 88.4 ± 1.7% (by 300 μM G-Ro) in thrombin-induced platelet aggregation (Fig. 2), we investigated whether G-Ro has dose (100, 200, 300 μM)-dependent effects on VASP (Ser157 or Ser239) phosphorylation in thrombin-activated platelets. G-Ro dose-dependently increased p-VASP (Ser157; Fig. 3A, Lanes 3–5), and the ratio of p-VASP (Ser157)-50 kDa to β-actin in thrombin-activated platelets (Fig. 3B). However, G-Ro did not affect phosphorylation of VASP (Ser239; Fig. 3C), even though G-kinase activator 8-Br-cGMP, a positive control, phosphorylated VASP (Ser239; Fig. 3C, Lane 6). This reflects the result that G-Ro does not increase the cGMP level (Table 1), and subsequently involve in phosphorylation of VASP (Ser239) in thrombin-activated platelets. Because G-Ro increased the cAMP level (Table 1), it is thought that G-Ro-increased VASP (Ser157) phosphorylation would be decreased by the A-kinase inhibitor. Accordingly, to observe an apparent inhibitory mechanism of cAMP/A-kinase on G-Ro-phosphorylated VASP (Ser157), we examined the effect of the A-kinase inhibitor on VASP (Ser157) phosphorylation by 300μM of G-Ro that potently phosphorylated VASP (Ser157; Fig. 3B). The A-kinase inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (Fig. 3D, Lane 4) potently decreased G-Ro (300μM)-phosphorylated VASP (Ser157; Fig. 3D, Lane 3), and the A-kinase activator pCPT-cAMP, a positive control, also phosphorylated VASP (Ser157; Fig. 3D, Lane 5). The results mean that G-Ro increases cAMP level (Table 1), and subsequently phosphorylates VASP (Ser157) in thrombin-activated platelets.

Fig. 3.

Effects of ginsenoside Ro (G-Ro) on vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) phosphorylation. (A) Effects of G-Ro on VASP phosphorylation. Lane 1, intact platelets (base); Lane 2, thrombin (0.05 U/mL); Lane 3, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (100μM); Lane 4, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (200μM); and Lane 5, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (300μM). (B) The ratio of phosphorylation of VASP (Ser157)-50 kDa to β-actin by G-Ro. Its ratio is from Fig. 3A. (C) Effects of G-Ro on VASP (Ser239)-50 kDa phosphorylation. Lane 1, intact platelets (base); Lane 2, thrombin (0.05 U/mL); Lane 3, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (100 μM); Lane 4, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (200μM); Lane 5, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (300 μM); and Lane 6, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + 8-Br-cGMP (1mM). (D) Effects of G-Ro on VASP (Ser157)-50 kDa phosphorylation in the presence of an A-kinase inhibitor (Rp-8-Br-cAMPS). Lane 1, intact platelets (base); Lane 2, thrombin (0.05 U/mL); Lane 3, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (300μM); Lane 4, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (300μM) + Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (250 μM); and Lane 5, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + pCPT-cAMP (1mM). Western blotting was performed as described in the “Materials and methods” section. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4). * p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets. ** p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets in the presence of G-Ro (300μM).

Table 1.

Effects of ginsenoside Ro (G-Ro) on cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) production1)

| cAMP (pmol/108 platelets) |

cGMP (pmol/108 platelets) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Basal | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.1 |

| Thrombin (0.05 U/mL) | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.1 |

| Thrombin (0.05 U/mL) | 10.9 ± 0.6* | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| + | ||

| G-Ro (300μM) |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 4)

*p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets

Determination of cAMP and cGMP was carried out as described in the “Materials and methods” section

3.3. Effects of G-Ro on the production of cAMP and cGMP

Because it is well established that cAMP and cGMP stimulate VASP phosphorylation [17], [18], we investigated the effect of G-Ro on the production of cAMP and cGMP in thrombin-induced platelet aggregation. As shown in Table 1, G-Ro increased the cAMP level in thrombin-induced platelet aggregation, but did not increase the level of cGMP.

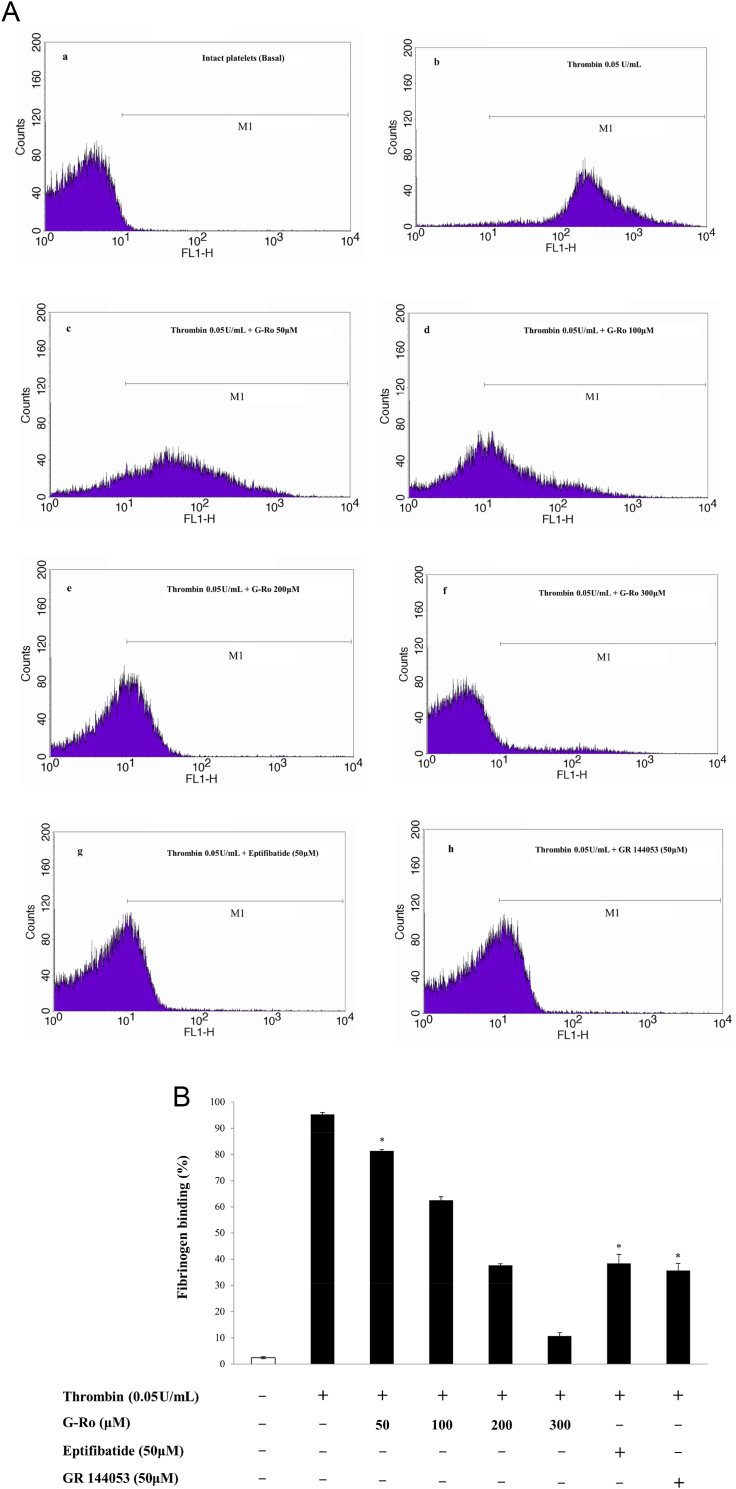

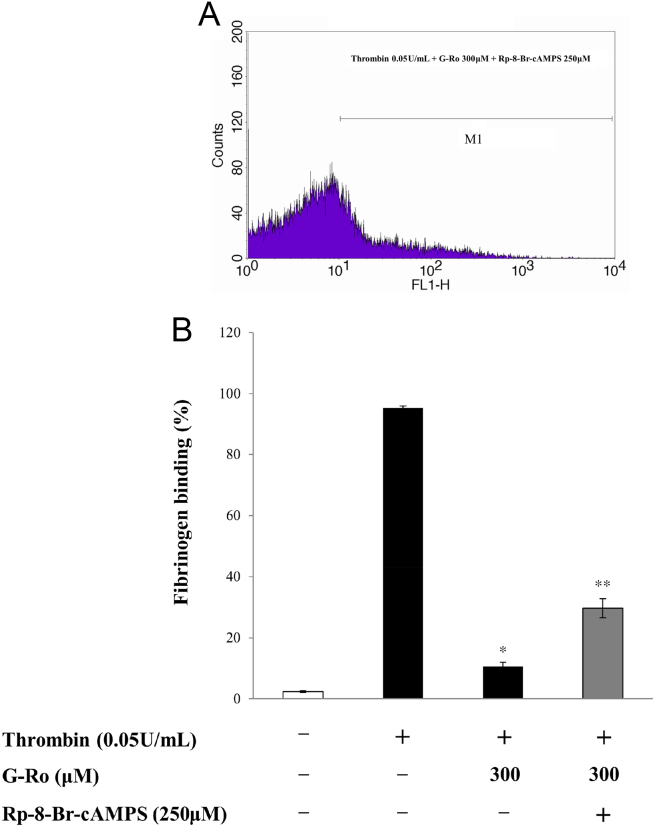

3.4. Effects of G-Ro on fibrinogen binding to αIIb/β3

Because VASP (Ser157) phosphorylation is involved in inhibition of fibrinogen binding, and G-Ro increased VASP (Ser157) phosphorylation (Fig. 3A), it is thought that G-Ro may decrease fibrinogen binding to αIIb/β3. G-Ro dose-dependently (100μM, 200μM, 300μM) activated the phosphorylation of VASP (Ser157) in thrombin-activated platelets (Fig. 3B). Therefore, we investigated whether G-Ro has dose-dependent (100μM, 200μM, 300μM) inhibitory effects on fibrinogen binding to αIIb/β3 in thrombin-activated platelets. Thrombin elevated fibrinogen binding to αIIb/β3 (Figs. 4A-b, 4B) and its degree was 95.3 ± 0.7% (Table 2). However, G-Ro attenuated the fibrinogen binding achieved by thrombin in dose-dependent manner (Figs. 4A-c–f, 4B), and the inhibitory degree by G-Ro (300μM) was 88.9% (Table 2) as compared with that (95.3 ± 0.7%) by thrombin. αIIb/β3 Inhibitors (eptifibatide, GR 144053), positive controls, inhibited thrombin-induced fibrinogen binding to αIIb/β3 (Figs. 4A-g, -h, 4B). Their inhibitory degrees were 38.4 ± 3.4% (at eptifibatide 50μM) and 35.7 ± 2.6% (at GR144053 50μM), which were almost equal to that (37.6 ± 0.6%) by G-Ro (200μM; Fig. 4B). As G-Ro increased the cAMP level (Table 1) and VASP (Ser157) phosphorylation (Fig. 3B), if the inhibition of fibrinogen binding by G-Ro (Fig. 4B) resulted from cAMP/A-kinase-mediated VASP (Ser157) phosphorylation (Fig. 3B), it is thought that G-Ro-decreased fibrinogen binding would be increased by the A-kinase inhibitor. To confirm that cAMP/A-kinase had an inhibitory effect on G-Ro-blocked fibrinogen binding, we examined the effect of the A-kinase inhibitor on inhibition of fibrinogen binding by 300μM of G-Ro (Fig. 4B) that potently inhibited fibrinogen binding. The A-kinase inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS increased G-Ro-inhibited fibrinogen binding to αIIb/β3 in thrombin-activated platelets (Figs. 5A, 5B), and its degree was increased to 179.2% as compared with that (10.6 ± 1.3%) by G-Ro (300μM) plus thrombin (Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Effects of ginsenoside Ro (G-Ro) on thrombin-induced fibrinogen binding. (A) The flow cytometry histograms on fibrinogen binding. a, intact platelets (base); b, thrombin (0.05 U/mL); c, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (50μM); d, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (100 μM); e, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (200μM); f, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (300 μM); g, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + eptifibatide (50μM); and h, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + GR 144053 (50μM). (B) Effects of G-Ro on thrombin-induced fibrinogen binding. Its binding degree (%) is from Fig. 4A. Determination of fibrinogen binding to glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (αIIb/β3) was carried out as described in the “Materials and methods” section. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). * p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets. FL1-H, fluorescent light-1 height.

Table 2.

Effects of ginsenoside Ro (G-Ro) on changes of fibrinogen binding1)

| Fibrinogen Binding (%) | Δ(%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intact platelets | 2.4 ± 0.4 | — |

| Thrombin (0.05 U/mL) | 95.3 ± 0.7 | — |

| G-Ro (300μM) | 10.6 ± 1.3 | −88.9 2) |

| + thrombin (0.05 U/mL) | ||

| G-Ro (300μM) | 29.6 ± 3.1 | +179.2 3) |

| + thrombin (0.05 U/mL) | ||

| + Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (250μM) |

Data presented are from Fig. 5B

Δ (%) = [(G-Ro + thrombin) − thrombin]/thrombin × 100

Δ (%) = [(G-Ro + thrombin + Rp-8-Br-cAMPS) − (G-Ro + thrombin)]/(G-Ro + thrombin)] × 100

Fig. 5.

Effects of ginsenoside Ro (G-Ro) on thrombin-induced fibrinogen binding in the presence of an A-kinase inhibitor (Rp-8-Br-cAMPS). (A) The flow cytometry histograms on fibrinogen binding. Thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (300μM) + Rp-8-Br-cAMP (250μM). (B) Effects of G-Ro on thrombin-induced fibrinogen binding in the presence of the A-kinase inhibitor (Rp-8-Br-cAMPS). Its binding degree (%) is from Fig. 4, Fig. 5A. Determination of fibrinogen binding to αIIb/β3 was carried out as described in the “Materials and methods” section. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4). * p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets. ** p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets in the presence of G-Ro (300μM). FL1-H, fluorescent light-1 height.

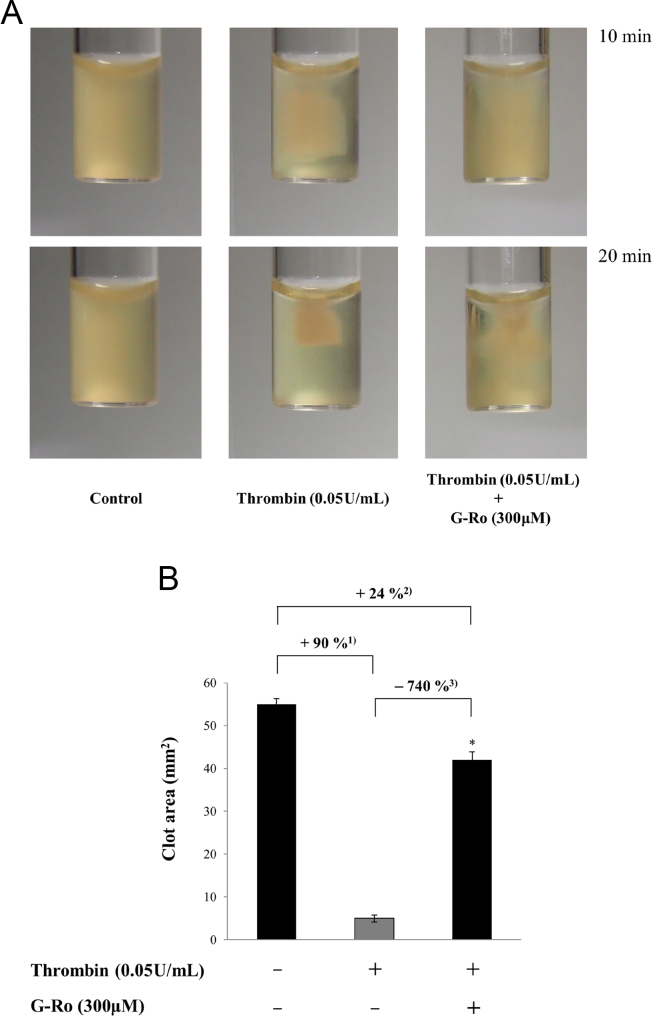

3.5. Effects of G-Ro on retraction of fibrin clot

The binding of fibrinogen is known to stimulate clot retraction to intensify the formation of thrombus [19], [20], [21]. Thus, we investigated whether G-Ro inhibits clot retraction. Thrombin reaction time-dependently (10 min and 20 min) accelerated the clot retraction (Fig. 6A), and its degree (at 20 min) was increased to 90% compared to that (55.4 ± 1.3 mm2) without thrombin, control (Fig. 6B). However, G-Ro very potently inhibited clot retraction by thrombin (Fig. 6A), which was attenuated up to 740% against that (5.5 ± 0.8 mm2) by thrombin (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Effects of ginsenoside Ro (G-Ro) on fibrin clot retraction. (A) Photographs of fibrin clot. (B) Effects of G-Ro on thrombin-retracted fibrin clot. Quantification of fibrin clot retraction was performed as described in the “Materials and methods” section. 1) (control − thrombin)/control × 100. 2) [control − (thrombin + G-Ro)]/control × 100. 3) [thrombin − (thrombin + G-Ro)]/thrombin × 100. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). * p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets.

4. Discussion

Intracellular cAMP and cGMP phosphorylate inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor type I (IP3RI) and VASP. The phosphorylation of IP3RI is connected to inhibition of [Ca2+]i mobilization by IP3, and the phosphorylation of VASP contributes to inhibition of fibrinogen binding to αIIb/β3. In a previous report, we found that G-Ro inhibits thrombin-elevated [Ca2+]i mobilization by phosphorylating IP3RI in a cAMP-dependent manner [22]. This means that G-Ro may be involved in inhibition of fibrinogen binding to αIIb/β3 by decreasing [Ca2+]i, and increasing cAMP. It is well established that intracellular Ca2+ activates αIIb/β3, and subsequently stimulates the binding of fibrinogen to αIIb/β3 [23]. If so, G-Ro that increases the level of the Ca2+-antagonistic molecule cAMP might be involved in inhibition of fibrinogen binding to αIIb/β3 via cAMP-dependent VASP phosphorylation. VASP (Ser157) is phosphorylated by cAMP/A-kinase, and VASP (Ser239) is phosphorylated by cGMP/G-kinase [17], [18]. In reality, G-Ro cAMP-dependently stimulated the phosphorylation of VASP (Ser157), but not phosphorylation of VASP (Ser239), which is evidenced as G-Ro increased the level of cAMP, but not cGMP. In addition, this is also supported from the results that the A-kinase inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS decreased G-Ro-increased VASP (Ser157) phosphorylation, and elevated G-Ro-attenuated fibrinogen binding to αIIb/β3.

The fibrinogen binding to αIIb/β3 intensifies the formation of thrombus [19] by stimulating the retraction of the fibrin clot, which accelerates the progression of atherosclerosis [24], [25]. Therefore, it is natural that G-Ro, inhibiting the fibrinogen binding, potently inhibits the retraction of the fibrin clot.

Platelet aggregation is connected to inflammation, a cause of atherosclerosis, and its associated proteins (platelet-derived growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, p-selectin, interleukin 1β, etc.) are secreted out of α-granules [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]. Even though G-Ro phosphorylates VASP (Ser157), it inhibits fibrinogen binding to attenuate thrombin-induced platelet aggregation, and fibrin clot retraction. If G-Ro dose not attenuate inflammation by leukocytes, antiplatelet effects by G-Ro would be doubtful. It is known that p-selectin is released by Ca2+, and subsequently interacts with monocyte to trigger inflammation [34]. G-Ro in a Ca2+-antagonistic action inhibited thrombin-induced expression of p-selectin [22], which means that the decrease of Ca2+ level by G-Ro might involve in inhibition of inflammation by suppressing thrombin-induced p-selectin secretion. This is also evidenced by results that G-Ro had anti-inflammatory activity in vivo and in vitro [35], [36]. These reports [35], [36] indicate that G-Ro may protect against thrombosis and atherosclerosis without inflammation.

The concentrations of G-Ro with antiplatelet effects (50–300 μM) are very low as compared with that 1mM of G-Ro attenuated arachidonic acid-induced platelet aggregation [12]. It is reported that G-Ro (10–50 mg/kg body weight-rat) administration activates fibrinolysis, an index of inhibition in fibrin thrombi [13]. Even though 300 μM (about 287 mg/kg) of G-Ro (MW. 957.1) has the anticlot retraction effect, it is unknown whether thrombin-induced clot retraction would also be inhibited in vivo through administration. However, because thrombin stimulates platelet aggregation and fibrin formation, it is thought that G-Ro 300μM (287 mg/kg) would be involved in attenuation of fibrin clot retraction.

In conclusion, we found inhibitory effects of G-Ro on fibrinogen binding to αIIb/β3, and clot retraction, which is mediated by cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of VASP (Ser157). From this study, we suggest that G-Ro is a novel compound of P. ginseng which inhibits fibrinogen binding to αIIb/β3.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant (NRF-2011-0012143 to H.J.P.) from the Basic Science Research Program via the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Korea.

References

- 1.van Willigen G., Akkerman J.W. Protein kinase C and cyclic AMP regulate reversible exposure of binding sites for fibrinogen on the glycoprotein IIB-IIIA complex of human platelets. Biochem J. 1991;273:115–120. doi: 10.1042/bj2730115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Payrastre B., Missy K., Trumel C., Bodin S., Plantavid M., Chap H. The integrin alpha IIb/beta 3 in human platelet signal transduction. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:1069–1074. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00417-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips D.R., Nannizzi-Alaimo L., Prasad K.S. Beta3 tyrosine phosphorylation in alphaIIbbeta3 (platelet membrane GP IIb-IIIa) outside-in integrin signaling. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:246–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laurent V., Loisel T.P., Harbeck B., Wehman A., Gröbe L., Jockusch B.M., Wehland J., Gertler F.B., Carlier M.F. Role of proteins of the Ena/VASP family in actin-based motility of Listeria monocytogenes. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:1245–1258. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sudo T., Ito H., Kimura Y. Phosphorylation of the vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) by the anti-platelet drug, cilostazol, in platelets. Platelets. 2003;14:381–390. doi: 10.1080/09537100310001598819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamruzzaman S.M., Yayeh T., Ji H.D., Park J.Y., Kwon Y.S., Lee I.K., Rhee M.H. p-Terphenyl curtisian E inhibits in vitro platelet aggregation via cAMP elevation and VASP phosphorylation. Vasc Pharmacol. 2013;59:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oh W.J., Endale M., Park S.C., Cho J.Y., Rhee M.H. Dual roles of quercetin in platelets: phosphoinositide-3-kinase and MAP kinases inhibition, and cAMP-dependent vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein stimulation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:485262. doi: 10.1155/2012/485262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lincoff A.M., Califf R.M., Topol E.J. Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade in coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1103–1115. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00554-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabatine M.S., Jang I.K. The use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 2000;109:224–237. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00474-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanada S., Kondo N., Shoji J., Tanaka O., Shibata S. Studies on the saponins of ginseng. I. Structures of ginsenoside-Ro, -Rb1, -Rb2, -Rc and -Rd. Chem Pharm Bull. 1974;22:421–428. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi K.T. Botanical characteristics, pharmacological effects and medicinal components of Korean Panax ginseng CA Meyer. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29:1109–1118. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuda H., Namba K., Fukuda S., Tani T., Kubo M. Pharmacological study on Panax ginseng CA Meyer. III. Effects of Red Ginseng on experimental disseminated intravascular coagulation. (2). Effects of ginsenosides on blood coagulative and fibrinolytic systems. Chem Pharm Bull. 1986;34:1153–1157. doi: 10.1248/cpb.34.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuda H., Namba K., Fukuda S., Tani T., Kubo M. Pharmacological study on Panax ginseng CA Meyer. IV. Effects of red ginseng on experimental disseminated intravascular coagulation. (3). Effect of ginsenoside-Ro on the blood coagulative and fibrinolytic system. Chem Pharm Bull. 1986;34:2100–2104. doi: 10.1248/cpb.34.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teng C.M., Kuo S.C., Ko F.N., Lee J.C., Lee L.G., Chen S.C., Huang T.F. Antiplatelet actions of panaxynol and ginsenosides isolated from ginseng. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;990:315–320. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(89)80051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin J.H., Kwon H.W., Cho H.J., Rhee M.H., Park H.J. Inhibitory effects of total saponin from Korean Red Ginseng on [Ca2+]i mobilization through phosphorylation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit and inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate receptor type I in human platelets. J Ginseng Res. 2015;39:354–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gambaryan S., Kobsar A., Rukoyatkina N., Herterich S., Geiger J., Smolenski A., Walter U. Thrombin and collagen induce a feedback inhibitory signaling pathway in platelets involving dissociation of the catalytic subunit of protein kinase a from an NFκB-IκB complex. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18352–18363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.077602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barragan P., Bouvier J.L., Roquebert P.O., Macaluso G., Commeau P., Comet B., Eigenthaler M. Resistance to thienopyridines: clinical detection of coronary stent thrombosis by monitoring of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein phosphorylation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2003;59:295–302. doi: 10.1002/ccd.10497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smolenski A., Bachmann C., Reinhard K., Hönig-Liedl P., Jarchau T., Hoschuetzky H., Walter U. Analysis and regulation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein serine239 phosphorylation in vitro and in intact cells using a phosphor specific monoclonal antibody. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20029–20035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Law D.A., DeGuzman F.R., Heiser P., Ministri-Madrid K., Killeen N., Phillips D.R. Integrin cytoplasmic tyrosine motif is required for outside-in αIIbβ3 signalling and platelet function. Nature. 1999;401:808–811. doi: 10.1038/44599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leclerc J.R. Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists: lessons learned from clinical trials and future directions. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:332–340. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205001-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Estevez B., Shen B., Du X. Targeting integrin and integrin signaling in treating thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:24–29. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon H.W., Shin J.H., Lee D.H., Park H.J. Inhibitory effects of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration by ginsenoside Ro are dependent on phosphorylation of IP3RI and dephosphorylation of ERK in human platelets. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:764906. doi: 10.1155/2015/764906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox J.E., Taylor R.G., Taffarel M., Boyles J.K., Goll D.E. Evidence that activation of platelet calpain is induced as a consequence of binding of adhesive ligand to the integrin, glycoprotein IIb-IIIa. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:1501–1507. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.6.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matter C.M., Schuler P.K., Alessi P., Meier P., Ricci R., Zhang D., Lüscher T.F. Molecular imaging of atherosclerotic plaques using a human antibody against the extra-domain B of fibronectin. Circ Res. 2004;95:1225–1233. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000150373.15149.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bültmann A., Li Z., Wagner S., Peluso M., Schönberger T., Weis C., Münch G. Impact of glycoprotein VI and platelet adhesion on atherosclerosis-a possible role of fibronectin. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:532–542. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castro-Malaspina H., Rabellino E.M., Yen A., Nachman R.L., Moore M.A. Human megakaryocyte stimulation of proliferation of bone marrow fibroblasts. Blood. 1981;57:781–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holash J., Maisonpierre P.C., Compton D., Boland P., Alexander C.R., Zagzag D., Yancopoulos G.D., Wiegand S.J. Vessel cooption, regression, and growth in tumors mediated by angiopoietins and VEGF. Science. 1999;284:1994–1998. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5422.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seppä H., Grotendorst G., Seppä S., Schiffmann E., Martin G.R. Platelet-derived growth factor in chemotactic for fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1982;92:584–588. doi: 10.1083/jcb.92.2.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz S.M., Ross R. Cellular proliferation in atherosclerosis and hypertension. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1984;26:355–372. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(84)90010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Packham M.A., Mustard J.F. The role of platelets in the development and complications of atherosclerosis. Semin Hematol. 1986;23:8–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartz S.M., Reidy M.A. Common mechanisms of proliferation of smooth muscle in atherosclerosis and hypertension. Hum Pathol. 1987;18:240–247. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(87)80006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagai R., Suzuki T., Aizawa K., Shindo T., Manabe I. Significance of the transcription factor KLF5 in cardiovascular remodeling. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:1569–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips D.R., Conley P.B., Sinha U., Andre P. Therapeutic approaches in arterial thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:1577–1589. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davì G., Patrono C. Platelet activation and atherothrombosis. New Engl J Med. 2007;357:2482–2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuda H., Samukawa K.I., Kubo M. Anti-inflammatory activity of ginsenoside Ro. Planta Med. 1990;56:19–23. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim S., Oh M.H., Kim B.S., Kim W.I., Cho H.S., Park B.Y., Kwon J. Upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 by ginsenoside Ro attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in macrophage cells. J Ginseng Res. 2015;39:365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]