Abstract

A unified theoretical framework for the recovery of second-order nonlinear susceptibility tensors and sample orientations from polarization-dependent second harmonic generation and sum frequency generation microscopy was developed. Jones formalism was extended to nonlinear optics and was used to bridge the experimental observables and the local-frame tensor elements. Four commonly used experimental architectures were explicitly explored, including polarization rotation with no postsample optics, polarization-in polarization-out measurement, and polarization modulation with and without postsample optics. Polarization-dependent second harmonic generation measurement was performed on Z-cut quartz and the local-frame tensor elements were calculated. The recovered tensor elements agree with the expected values dictated by symmetry.

Introduction

Second harmonic generation (SHG) has been widely used as an imaging contrast mechanism for the visualization of biological tissue, cells, and chiral crystals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). Arising only from noncentrosymmetric structures, SHG microscopy offers selective detection of ordered systems with high speed and sensitivity. The development of polarization-dependent SHG has greatly expanded the information content and application space of SHG microscopy by providing a secondary contrast mechanism along with the second harmonic intensity. The unique symmetry requirements and the coherent nature of the second harmonic process make SHG microscopy particularly sensitive to polarization-dependent measurement. The efficiency of the generation of the doubled light depends on both the polarization state of the incident light and the orientation of the SHG active portion within the local reference frame. Information on the microscopic organization and orientation of cells, collagen fibers, and protein crystals can be extracted from polarization-dependent SHG measurements (9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19).

Several strategies have been explored for polarization manipulation in SHG microscopy, including combinations of waveplates, polarizers, and phase-modulation components for both excitation and detection. Using manual waveplate rotation, Stoller et al. (20) investigated the back-scattered SHG from rat-tail tendon as a function of a series of linear polarization states, experimentally determining the ratio between two of the nonzero nonlinear susceptibility tensor elements. In studies by Plocinik and Simpson (10), complex components in the tensor elements were directly recovered by a null ellipsometric configuration. In a study of photothermally induced disorder of corneal collagen, a series of linear polarization states was generated through rotation of a linear polarizer before the sample (21). Polarization-in, polarization-out (PIPO) SHG was used to study human lung tissue where, in addition to the polarization optics before the sample, a linear polarizer was also installed before the SHG detectors (14, 22). Alternatively, Stoller et al. (11) demonstrated fast phase modulation (access to elliptical and circular polarization states) with an electro-optic modulator (EOM). Polarization-dependent vibrational sum frequency microscopy has recently added new spectroscopic information to nonlinear chemical imaging (23).

While many of these studies target the examination of collagen and other similar biological systems, the diversity in the optical paths and analysis methodologies makes it difficult to compare results between different experiments. Even for optical paths designed using similar elements but in different locations, substantially different analysis algorithms are routinely independently used to interpret the results. The early foundations for molecular-level interpretation of polarization-dependent nonlinear optical measurements were arguably laid in surface science studies (24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29). However, conventions for mapping of these mathematical architectures to microscopy measurements are not universal. The increasing use of polarization-dependent SHG calls for a general architecture for data analysis that is suitable for comparing experimental results across a large diversity of varying experimental configurations and desired observables.

The goal of this work is to provide a unified theoretical foundation for quantitatively connecting the nonlinear optical properties at the molecular level to the polarization-dependent SHG intensities measured in many of the most commonly employed polarization-dependent sum frequency generation (SFG) and SHG microscopy architectures. A general, matrix-based mathematical approach depicted in Fig. 1 is presented here, in which the measured intensity can be described through knowledge of the input polarization, the orientation of the sample within the laboratory frame, the local field effects, the symmetry of the sample, and the unique local frame second-order tensor of the sample, . In brief, a two-step analysis is performed, the first of which is recovery of a phenomenological model-independent Jones tensor, followed by subsequent steps to relate the Jones tensor back to desired local-frame properties within the field of view. By analogy with linear optics, the Jones tensor is a polarization transfer tensor. Knowledge of all elements within the Jones tensor allows prediction of the Jones vector for the SFG or SHG produced for any combination of incident-driving fields. Also, by analogy with linear optics, the Jones tensor will generally contain complex-valued elements.

Figure 1.

General process for conversion of polarization-dependent SHG intensities to vectorized unique local-frame tensor. Conversion from intensity to a vector of polynomial coefficients requires knowledge of the incident polarization. Conversion between the vectorized Jones tensor in the laboratory frame and the vector of the full set of local frame tensor elements requires knowledge of the sample orientation and refractive index of the media. Contracting the full set of 27 possible values of local-frame tensors to just the remaining unique, nonzero elements requires prior knowledge of the symmetry of the sample.

The Jones tensor architecture has the distinct advantage of allowing for clear separation of model-independent measurements of the Jones tensor and subsequent model-dependent analyses to recover local-frame information (e.g., orientation analysis or local-frame tensors). Because this second step often involves some set of assumptions or approximations, the Jones tensor formalism provides a convenient reference point for which multiple different models based on different hypotheses may be compared to the model-independent Jones measurements. Finally, even if the Jones tensor elements are themselves not directly recorded or used in the analysis, their introduction serves as a convenient intermediate step in the mathematical analysis.

Materials and Methods

Assumptions of the model

The following simplifying assumptions are used in the derivation of the expressions below: 1) the paraxial approximation, consistent with the use of a low numerical aperture (NA) objective (i.e., NA ∼<0.8) such that the local electric field within the focal volume can be approximated as a local Gaussian/plane wave (30) (this assumption holds for most microscopy measurements where an immersion objective is not used); 2) the absence of chromic aberrations and astigmatism in the beam path; 3) the negligible scattering or depolarization of the incident or detected light, such that the polarization states of both the fundamental and second harmonic beams can be accurately described by Jones vectors; and 4) the thin sample limit, such that the SHG source can be modeled as a plane wave source where the sample thickness is less than or comparable to the depth of focus, in which case the absolute phase shift between the fundamental and SFG or SHG across the sample volume is negligible and the Jones vector describing the local polarization remains unchanged throughout the focal volume. (Detailed discussion about measurements made with a high NA objective or thick samples can be found in Pavone and Campagnola (31).)

Birefringence can influence polarization-dependent SHG microscopy measurements in two important ways. The driving polarization state experienced locally by the sample can be substantially different from that introduced in the far-field, with similar perturbations also arising between the SHG produced locally and that detected in the far field. Perturbations to the fundamental beam from sample birefringence can be addressed through the knowledge of the Jones matrix describing the birefringence effect. For the discussion presented here, we assume the sample thickness is sufficiently thin so that the birefringence of the sample is negligible for the analysis. For effects preceding or following the generation of SHG, perturbations from birefringence can be included using the mathematical approaches including postsample optics.

In addition, it is assumed that the incident light is sufficiently transparent to the medium such that effects from saturation, local heating, etc., negligibly perturb the nonlinear optical measurements. In the most common SHG microscopy measurements of biological samples, neither the incident nor detected frequencies are resonant with strong electronic transitions, consistent with this assumption.

General framework for polarization-dependent SFG measurements

The extension of the Jones formalism to nonlinear optics is significantly more transparent and straightforward with respect to book-keeping in the most general case of SFG. SHG will then be considered explicitly as a specific example of this more general architecture.

Within the limit of the assumptions made in the previous subsection, Jones vector representations are fully capable of describing the polarization state through the entire optical path. With the knowledge of Jones transfer matrices, all linear polarization-dependent observables can be uniquely predicted through matrix multiplication. Furthermore, in the context of polarization-dependent imaging, where reference frame transformation is common, Jones matrices are particularly convenient for describing optical elements that are rotated relative to the laboratory frame simply by incorporation of rotation matrices to change reference frames.

The Jones vector for light of frequency ω in any microscopy measurement is shown in Eq. 1, where the subscript L indicates polarization-dependent experimental observables measured in the laboratory frame and the subscripts H and V indicate the horizontal and vertical optical fields, respectively:

| (1) |

By extension to second-order nonlinear optics, an analogous Jones tensor can be written to describe the observed polarization-dependent output measured experimentally in terms of the driving fields. This phenomenological eight-element 2×2×2 tensor, of which all eight elements are unique in the most general case of SFG, is effectively a polarization transfer tensor, completely describing the expected polarization state generated experimentally for any combination of incident polarization states (32). Consequently, the Jones tensor ultimately contains all the information experimentally accessible in a single measurement configuration.

Mathematically, the Jones vector of the detected light can be written in terms of the incident polarization state as a matrix product by vectorizing the Jones tensor, as shown in Eq. 2:

| (2) |

With the Jones tensor written as a vector, multiplication by a matrix describing the polarization state of the driving fields yields the Jones vector of the SFG . The vectorized form has some distinct practical advantages when pooling multiple polarization-dependent measurements. Under appropriate conditions, the problem can be inverted to recover the Jones tensor elements from polarization-dependent SHG measurements.

With representing the vectorized Jones tensor, Eq. 2 can be rewritten as the product of a vector of Jones tensor elements with a matrix of driving electric fields:

| (3) |

Each of the and tensor elements consists of a two-element complex-valued Jones column vector describing the polarization state of the driving fields. Any additional nondepolarizing optics placed in the beam path following generation of the SFG/SHG signal can be collectively described by a Jones matrix M:

| (4) |

The nth polarized electric field is given by the product of the vectorized Jones tensor and the nth row of the 2×8 matrix M•E. The detected n-polarized intensity is proportional to the squared magnitude of the corresponding electric field:

| (5) |

| (6) |

Taking advantage of the property of complex conjugates together with the associative property of Kronecker products, the above equations can be rewritten in the following form:

| (7) |

At this point, we have demonstrated the expression of the detected SFG intensity in terms of Jones tensor and input electric fields for the most general case. The framework isolates the Jones tensor element products, and breaks the electric field components into four clear blocks. Because of the significant number of elements within the direct product (82 = 64), it can be challenging just to keep track of the electric field products with matching tensor element products. Fortunately, this block architecture allows the development of a binary coding/decoding system where the polarization components in ea and eb are indicated by a binary number 0 or 1 at the corresponding index location. Details about the binary system and the application are described in the Supporting Material.

Specific case for polarization rotation with a fixed polarizer and no postsample optics

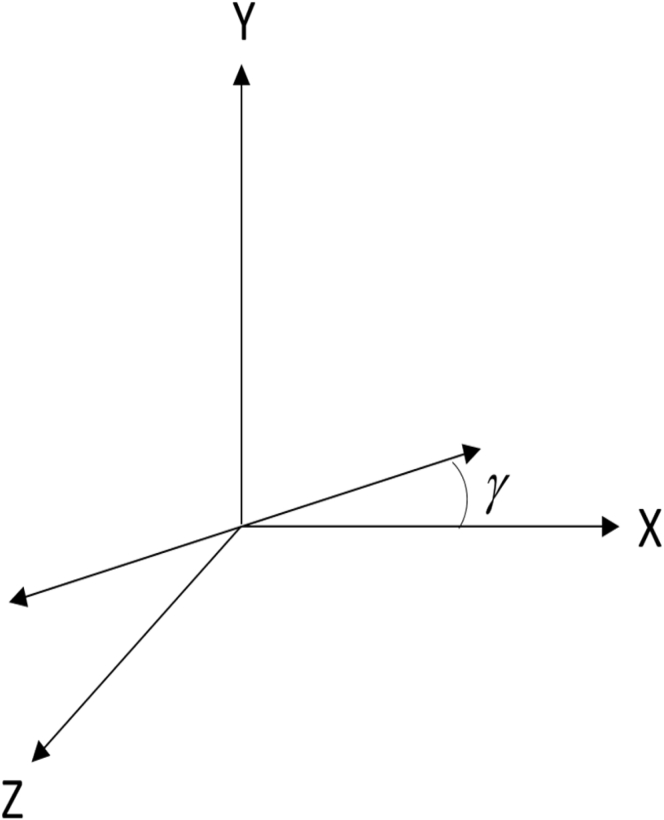

The next step is to start populating the electric field products for several common cases and build the bridge to mathematically recover Jones tensor elements. One of the more common and conceptually simpler cases will be considered first, in which the polarized SHG is detected as a function of the rotation angle of a linearly polarized incident beam (Fig. 2). This configuration can be achieved by starting with circularly or unpolarized incident light that is passed through a polarizer rotated an angle γ, or by rotation of a half-wave plate by an angle γ/2 for linearly polarized incident light.

Figure 2.

Definition of γ using a Cartesian coordinate system. Horizontal corresponds to X and vertical to Y.

For linearly polarized incident light, the driving electric fields are given by a simple Jones vector:

| (8) |

In this case, Eq. 7 can be rewritten in the following form by explicitly evaluating the product along with the simplification and for SHG. The corresponding SHG intensity is given by the squared magnitude of :

| (9) |

For n-polarized detection in the laboratory frame, the following analytical expression emerges:

| (10) |

The parameter n can correspond to either H or V polarizations by substitution of the first χ-index position throughout in the above equation. The SHG intensity as a function of γ can be rewritten as the expression below by separating the five different parameters:

| (11) |

The five polynomial coefficients, which ultimately depend on three Jones tensor elements, are related to the tensor element products through the following equalities:

| (12) |

| (13) |

While the individual Jones tensor elements cannot be solved directly through direct inversion of the above equations, nonlinear fitting of either the polynomial coefficients or the raw intensity data allows determination of the tensor elements. Because all tensor elements appear as products, at least two equivalent solutions will always emerge, reflecting the ambiguity of the absolute sign of each tensor elements.

Equation 6 can be rewritten in the following linear algebra form, by introducing a matrix P relating the polynomial coefficients to the tensor element products. In the most general case of SFG, P will be a 5×16 sparse matrix relating the n-polarized SFG to Kronecker product of the four nonzero tensor elements , , , and . In the specific case of SHG, a simplified 5×9 version below can be written by using the equality :

| (14) |

This relationship can be recast more concisely by expressing the tensor products as a Kronecker product and substitution for the matrix P:

| (15) |

Combining Eqs. 12 and 15, we have constructed the framework to solve for the Jones tensor elements.

In general, P cannot be directly inverted to isolate the χ(2) tensor element products in the most general case of complex-valued tensor elements, as the number of unknowns (six) exceeds the five observables. However, one of those parameters can be removed by considering relative phase referenced to one of the tensor elements, allowing matching of the number of unknowns and observables. Alternatively, pooling of results from multiple unique measurement configurations can lead to an invertible matrix.

As seen in numerous previous studies, Fourier decomposition formalism is also commonly used to describe the polarization dependent measurement (33, 34, 35, 36). An analogous set of relationships can be derived if one performs the fitting to a Fourier set of sine and cosine functions given in the equation below instead of the polynomial series in Eq. 12:

| (16) |

The corresponding set of equations relating the Fourier coefficients a through e above with the contracted tensor products is then given by the following expression with matrix F bridging the two:

| (17) |

Trigonometric relationships allow conversion between the set of polynomial coefficients, , and the Fourier coefficients, , expressed in matrix notation in the equation below:

| (18) |

| (19) |

This same transformation matrix T allows conversion between the corresponding matrices P and F:

| (20) |

In this case, both the five unique polynomial coefficients and the Fourier coefficients can be related back to the detected polarization-dependent intensity. However, the polynomial coefficients have the practical advantage of resulting in fewer nonzero entries in the transformation matrix P. Furthermore, the analogous matrix F can be populated by simple matrix multiplication once P has been determined through the equalities in Eq. 20.

General case of polarization rotation with postsample optics, including the specific case of polarization-in polarization-out measurements

The particular case of PIPO (14, 37) differs from the case discussed in Specific Case for polarization Rotation with a Fixed Polarizer and No Postsample Optics through the addition of a postsample polarizer. The effect of the polarizer can be described using a Jones matrix M calculated from the product of a Jones matrix for a polarizer set to pass 0-polarized light in the polarizer reference frame and a rotation matrix:

| (21) |

The convention of reference frame transformation used in this work is described in detail in the Supporting Material. It is worth noting that the rotation matrix to convert back to the laboratory-frame was not included in the preceding equation. The intensity detected following the polarizer will be identical in any choice of reference frame, assuming the detector itself exhibits no polarization-dependence in its sensitivity.

The simplicity of the case in Specific Case for polarization Rotation with a Fixed Polarizer and No Postsample Optics allows relatively straightforward analytical derivation of the product of Jones tensors and electric fields. In this case, the binary coding approach first introduced in the General Framework for Polarization-Dependent SFG Measurements is used and detailed in the Supporting Material.

With the Jones vector of the incident light described by Eq. 8, the corresponding binary products are given by the following combinations, with 0 corresponding to the first polarization component (e.g., horizontally polarized, or p-polarized) and 1 to the second component (e.g., vertically polarized, or s-polarized) and the asterisks indicating unassigned elements:

| (22) |

In the above expression, all tensor products with third and sixth positions equal to 0 and 0 (corresponding to ∗∗0∗∗0) introduce a factor of , all tensor products with the second and fifth positions equal to 1 and 0 (corresponding to ∗1∗∗0∗) introduce a factor of , etc. Pooling these products into a combined direct γ-dependent component set of terms yields the following:

| (23) |

Combining the binary encoding of the polarization-dependence with the matrix M for the postsample optics allows one to predict the detected intensity for any incident polarization rotation angle γ. Explicit examples are provided for 0-polarized detection, with a route to populate all the terms for 1-polarized detection generated from them in a later step. In this limit of 0-polarized detection, the intensity depends on up to five unique trigonometric terms dependent as a function of the rotation angle γ:

| (24) |

From the above set of equations, the general expression for A0 emerges:

| (25) |

Using the binary counting approach for 000000, 000100, 100000, and 100100, the elements corresponding to the 0th, 4th, 32nd, and 36th column positions in P, respectively, all contribute to the intensity information in the coefficient A0 (corresponding to the 0th row of P). Taking advantage of the relation , three unique equalities emerge:

| (26) |

The expressions for B0-E0 can be populated through the same basic approach, yielding the following expressions:

| (27) |

| (28) |

| (29) |

| (30) |

The corresponding set of nonzero elements in the sparse matrix P for the orthogonally polarized intensities can be generated simply be replacing the |M0,0|2 with |M1,0|2, with , and |M0,1|2 with |M1,1|2. It will be assumed that the set of A1-E1 coefficients is stacked on top of the five A0-E0 coefficients (rows 0–4 in P), such that the sixth row of the matrix P corresponds to A1, etc.:

| (31) |

Specific case of PIPO

Combining the matrix M in Eq. 21 with the expression of A0 in Eq. 25, the explicit expression of A0 for PIPO measurement emerges:

| (32) |

Similar evaluation is performed for coefficients B0-E0, and the result can be summarized in the following matrix form:

| (33) |

From Eq. 33 above, it should be clear that 15 independent observables are potentially accessible for SHG in a PIPO measurement. Each set of rotation measurements of the output polarizer depends only on three parameters given in the matrix above, with five parameters accessible upon rotation of the incident polarization state. The first and third columns in the matrix in Eq. 33 correspond, as expected, to the 10 parameters accessible with a fixed polarizing beam-splitter and two detectors.

Based on these results, it should be clear that a complete PIPO analysis can be performed from a set of at least 15 images to access all the available observables. Acquisition of additional images may significantly improve the confidence in the recovered results and can allow for error analysis by making the measurements overdetermined, but at the expense of additional time for data acquisition.

Specific case for polarization modulation SHG and 2PEF microscopy with no postsample optics

Polarization of the incident light can also be controlled through phase modulation. One commonly used architecture is discussed in this section and alternative configurations can be derived fairly straightforwardly using the approach described herein by propagating the Jones matrices accordingly. The derivation of the analytical expressions can be done through linear algebra conversion as demonstrated in Specific Case for polarization Rotation with a Fixed Polarizer and No Postsample Optics. However, the binary coding approach is used here, providing great improvement in clarity when populating the matrix P.

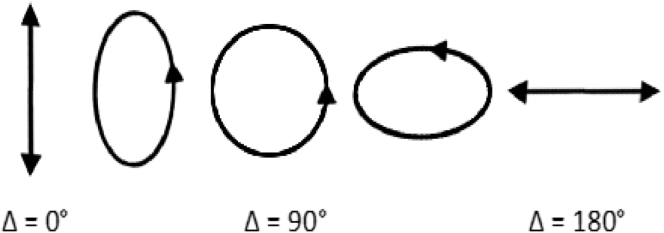

For horizontally polarized light introduced into a phase modulator (e.g., EOM, or photoelastic modulator) oriented −45° as shown in Fig. 3, the driving electric field can be written as follows, where Δ is the phase difference between the fast and slow axes of the EOM/photoelastic modulator and is time-varying:

| (34) |

Following closely the derivation of Eqs. 22 and 23, an analogous set of binary coded expressions can be derived with the incident electric field described in Eq. 34:

| (35) |

| (36) |

From inspection of the above equation, only five unique trigonometric terms emerge from the direct product (mirroring the previous treatment considering polarization rotation in “Specific Case for polarization Rotation with a Fixed Polarizer and no Postsample Optics” and “General Case of Polarization Rotation with Postsample Optics, Including the Specific Case of Polarization-In Polarization-Out Measurements”):

| (37) |

Similarly, a matrix P can be introduced connecting the polynomial coefficients and the Jones tensor elements. According to Eq. 14, the first row of the matrix P corresponds to A0. In the absence of additional optics following the sample, the matrix M in Eq. 7 is given by the identity matrix, and only the Jones tensor elements with 0 in the first and fourth positions will contribute to the detection of 0-polarized SHG (corresponding to 0∗∗0∗∗). In this case, A0 is described exclusively by the (000000) combination:

| (38) |

The binary number (000000) corresponds to the decimal number 0, such that the first row of the matrix P contains just a single entry:

| (39) |

Analogous approaches are used to populate the other five rows of P (corresponding to coefficients B0-E0). The following equations emerge:

| (40) |

| (41) |

| (42) |

| (43) |

The corresponding set of nonzero elements in the sparse matrix P for the orthogonally polarized intensities can be generated by considering the 1∗∗1∗∗ tensor products. The corresponding set of P matrix elements that are accessible in the measurement can be determined simply by adding 100100 to all the binary representations of the tensor element products, which corresponds to addition of 36 = 100100 to every one of the column indices of P. For example, C1 is recovered by the following set of nonzero elements of P:

| (44) |

Combining the relations , , and the interchangeability of the rightmost two indices for SHG, the expressions for coefficients B0-D0 that are similar to Eq. 6 can be retained by recasting the above expression in terms of real and imaginary combinations of the tensor elements, as follows:

| (45) |

As demonstrated in previous sections, knowledge of matrix P allows the recovery of Jones tensor elements through nonlinear fitting of the raw intensity to Eqs. 12 and 15.

Figure 3.

Resulting polarizations as a function of modulation of the phase shift, Δ, between the horizontal and vertical components of the input beam. The case pictured above implies a vertically polarized starting polarization, with the axis of modulation rotated to −45° according to the right hand rule with the Z axis defined co-parallel with the Poynting vector.

Polarization modulation SHG microscopy with additional postsample optics

Once generated, the polarization state of the signal can be subsequently affected by optics placed between the sample and detector. These optics can be placed intentionally to affect polarization (e.g., waveplates) or arise from parasitic effects related to optical path design (e.g., a mirror placed at an angle). Irrespective of their origin, the net impact of all nondepolarizing optical elements can be expressed as a single 2×2 Jones matrix, given by the Jones matrix product for each individual element.

The population of matrix P in this particular case closely follows the description in the Specific Case for polarization Rotation with a Fixed Polarizer and no Postsample Optics and the General Case of Polarization Rotation with Postsample Optics, Including the Specific Case of Polarization-In Polarization-Out Measurements, but with a nonspecific form for the matrix M and the appropriate Jones vector for the incident fields described in Eq. 34. Using the binary coding approach, a set of analogous expressions for the coefficients can be derived. The final results resemble Eqs. 25–30 closely, with minor differences in signs:

| (46) |

The full expression is not explicitly listed here for simplicity, but can be found in the Supporting Material.

Recovery of the local frame tensor and/or orientation from the Jones tensor

In this section, connections are built to bridge the laboratory-frame observables to the central parameters of interest: the local-frame tensor and orientation. The local-frame nonlinear susceptibility tensor describes the nonlinear optical property of the sample independent of the sample orientation within the laboratory reference frame, reflecting structural information of the sample (38). Jones tensors are connected to the local-frame tensors through three major factors: (1) the symmetry of the sample to reduce the total number of unique nonzero elements in the local tensor; (2) the local field correction factor; and (3) the orientation of the sample within the laboratory frame. In this section, Kronecker products are routinely used to expand matrices to larger dimensionality. For example, if the local field correction factor for one frequency (e.g., the doubled frequency) is given by the 3×3 matrix L2ω, the expanded 27×27 product of three local field correction factors is given by , with the bolding indicating the expanded form given by the Kronecker product of three matrices. Similar notation is used for other applicable matrices as well. Combining everything, the relationship between the Jones tensor and the unique elements within the local tensor is given by the following general equation, where L, J, and Q account for local field effects, rotation into the Jones frame, and the unique nonzero tensor elements, which is discussed in Incorporation of Local Field Correction Factors, and Rotation Matrix, J, Connecting the Local Reference Frame and the Jones Reference Frame, respectively. This process is depicted in Fig. 4:

| (47) |

Although the individual matrices comprising each term can be quite large in dimension, the overall matrix product relating the Jones tensor to the unique elements in the local-frame tensor is often quite tractable. In the case of n unique local-frame tensor elements, the dimensions of , L, and Q correspond to (8×27), (27×27), and (27×n), respectively, for a total product matrix of just (8×n). It is worth emphasizing that the vectorized local-frame tensor given by (or equivalently by in tensor notation) is still a local-frame susceptibility tensor, and should not be confused with the molecular-frame nonlinear polarizability typically denoted as . The local-frame tensor is generated through yet another stage of coordinate transformation by ensemble averaging over the orientation distribution of the individual molecular-frame tensor elements in , weighted by the bulk number density (39).

Figure 4.

General relationship between the electric field in laboratory frame and the local-frame tensor elements. The total number of unknowns is reduced through the local symmetry operation of the sample. Local field factors affect the effective electric field in the local reference frame. Finally, orientation of the sample in lab frame is used to perform reference frame transformation.

The influence of local symmetry and parameter reduction

The introduction of local-frame symmetry either in the sample (e.g., collagen or a crystal) or in the measurement can significantly reduce the number of nonzero elements in the effective local tensor. In turn, the number of unique elements in the local-frame tensor dictates the number of measurements that must be pooled to recover a unique solution for the local-frame tensor products. The total number of unique elements in local-frame tensor is 33 = 27; due to the interchangeability of SHG, this number is reduced to 18. A tabulated list of all symmetry-allowed tensor elements based on different molecular point groups and corresponding crystal classes is provided in Shen (39) and Boyd (40). The relation between the full set of tensor elements and the unique nonzero elements is bridged by the matrix Q:

| (48) |

The vector contains only the unique nonzero elements in the local-frame tensor. Q is a 27×n matrix, where n is the number of unique nonzero elements.

The case of azimuthal rotation and out-of-plane tilt of an assembly with local C∞ symmetry is considered here as a working example to illustrate the general approach. For C∞ symmetry, only seven unique tensor elements emerge in the local-frame from the sample symmetry alone: , and . In the case of SHG, the last two indices must be interchangeable by nature of the symmetry of the measurement, which reduces the number of unique nonzero elements down to just four; , and . The corresponding 27×4 symmetry matrix Q is then given by the following equation:

| (49) |

The matrix Q will consist largely of zeros, but will have four nonzero entries in the first column (Q6,1 = 1, Q8,1 = 1, Q12,1 = −1, and Q16,1 = −1) corresponding to the equality ; four nonzero entries in the second column (Q3,2 = 1, Q7,2 = 1, Q15,2 = 1, and Q17,2 = 1) corresponding to ; two nonzero entries in the third column (Q19,3 = 1, and Q23,2 = 1) for ; and finally, an entry of Q27,4 = 1 in the last row and column to account for .

Incorporation of local field correction factors

Within the paraxial approximation, changes to the polarization state as a result of gentle focusing (i.e., NA < ∼0.8) are negligible and can be largely ignored for all but the most precise measurements. For most microscopy measurements not requiring immersion objectives, the paraxial approximation is reasonably accurate, which assumes that the refraction angle θ for each ray emerging from the objective can be approximated using sinθ ≅ θ. It is worth noting that the paraxial approximation is not necessary for recovery of a Jones tensor. In the far-field, the incident and detected polarization states are still measured as plane waves, such that the sample can still be phenomenologically treated mathematically by an effective vectorized Jones tensor, .

An SHG or SFG point source embedded in a dielectric medium will experience perturbations to the local fields from the local dielectric properties that affect the far-field measurements. The simplest analytical expressions used to describe the local dielectric environment are the Lorentz corrections, which are simply multiplied by the local tensor to generate an effective local tensor:

| (50) |

The Lorentz scaling factors can be written as elements of diagonal matrices of the following form, with the coordinates defined in the local reference frame:

| (51) |

The Lorentz model given in Eq. 51 represents a zero-order correction based on an approximating the local dielectric environment by an ellipsoid defined about the local-frame coordinates. However, it should be clear that more elaborate models, such as those developed by Munn (41) or Wortmann and Bishop (42), to cite two examples, can be integrated with similar ease into the general architecture developed in this work simply by changing the elements in the L matrices. Wortmann and Bishop (42) have estimated that the Lorentz corrections are only accurate to ∼80%, but their use illustrates how such corrections could be integrated into the larger theoretical framework of this study.

Typically, an identical form is also used for the local field corrections rescaling the SHG output, but with the optical constants evaluated at the doubled frequency. It should be noted that generally a uniaxial system (e.g., a thin fiber or membrane) will exhibit an anisotropic refractive index. With the z axis defined as the unique axis, the local dielectric constant may need to be evaluated separately with nx = ny = no and nz = ne (i.e., the ordinary and extraordinary refractive indices of the fiber, respectively). In cases where no significant changes in refractive index is observed and in isotropic systems, the matrix L is proportional to the identity matrix, yielding an overall intensity scaling factor in the detected intensity.

Most generally, the influence of the local field corrections can be incorporated mathematically by multiplication of the 27 element χ(2) vector by a 27×27 matrix generated from the double Kronecker product of the three L matrices:

| (52) |

| (53) |

In the preceding equation, Q is the symmetry matrix relating the full set of all 27 local-frame tensor elements (i.e., ) to the smaller subset of unique elements given by (see The Influence of Local Symmetry and Parameter Reduction).

Rotation matrix, J, connecting the local reference frame and the Jones reference frame

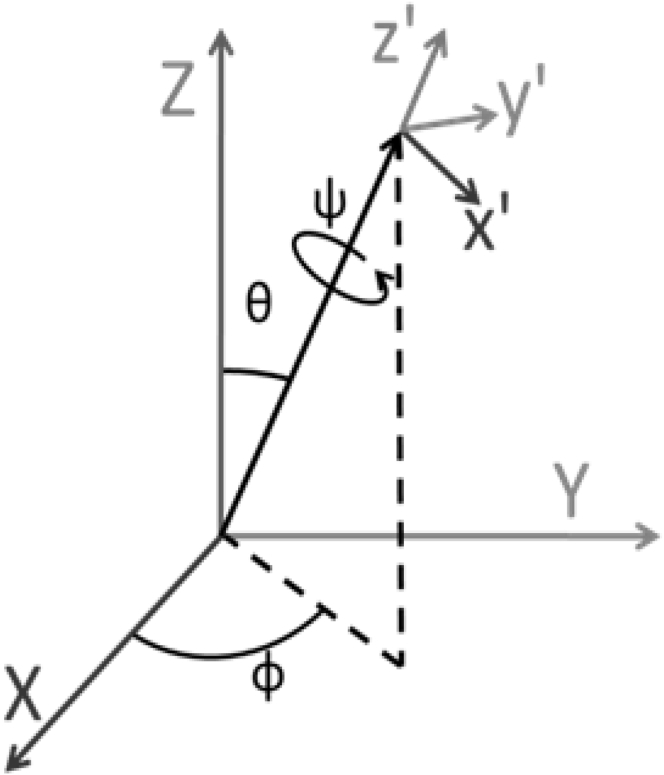

In general, the samples probed in a microscopy measurement will not be perfectly aligned with the laboratory coordinates, with rotation operations providing the mathematical framework to perform the coordinate transformations. With the formalism now in place to bridge the local and macroscopic fields, one final task remains to couple the Jones tensor with the local-frame tensor: rotation of the field-corrected local-frame tensor into the Jones (laboratory) reference frame, as depicted in Fig. 5. Again, the process will be cast as a matrix multiplication using vectorized tensors. The expression for the full set of 27 field-corrected local tensor elements is given in Eq. 54. The Jones tensor is recovered through multiplication by one additional matrix J, which relates the two reference frames:

| (54) |

In this work, all rotation matrices are defined based on extrinsic rotations using the Z-Y-Z convention, as detailed in the Supporting Material. For example, if we desire to describe a vector initially defined in the (x′,y′,z′) coordinate system instead of in the (X,Y,Z) reference frame, projection onto the laboratory axes is performed using a rotation matrix:

| (55) |

In the case of the Jones reference frame, the polarization of the propagating detected plane wave is entirely described by the two H and V coordinates orthogonal to the propagation direction, which is defined as the Z axis. This last operation to remove the last Z-coordinate to recover a Jones vector in terms of H and V can be performed by multiplication by a truncated identity matrix IJ:

| (56) |

| (57) |

As before, rotation of a tensor instead of a vector is achieved by expanding out this vector operation using a double Kronecker product to generate the 23 × 33 = 8 × 27 matrix J:

| (58) |

The eight-element Jones tensor is generated from multiplication of the effective local-frame tensor by J:

| (59) |

and the corresponding polarization state of the exiting beam is given by the following equation:

| (60) |

Matrix J contains 216 elements even through it only depends on three Euler angles; and a full set of effective local-frame tensor contains 27 elements. It may appear intimidating to explicitly evaluate the above equation. However, this approach describes a framework in which a diverse array of polarization-dependent measurements of both low and high symmetry samples can be analyzed. In addition, the overall dimensionality can be substantially reduced systematically through multiplication by the symmetry matrix Q described in The Influence of Local Symmetry and Parameter Reduction and through simplifying assumptions with respect to the sample orientation distribution.

Figure 5.

Depiction of the Euler angles involved in rotating a point from the x′,y′,z′ coordinate system to the X,Y,Z coordinate system or vice versa. ϕ is the azimuthal angle, θ is the polar angle, and ψ is the twist angle.

Experimental

In previous work, nonlinear optical Stokes ellipsometric microscopy allowed recovery of laboratory-frame Jones tensor elements of the sample. However, the Jones tensor depends on both the orientation of the sample and the local structure. In this work, we have significantly extended the analysis to the recovery of local-frame tensors as well as the orientation of the sample. The recovered local-frame tensor elements of Z-cut quartz are presented here as an initial validation of the mathematical framework with established local-frame nonlinear optical properties.

Polarization-dependent SHG intensity was measured at a different quartz rotation angle in the transmitted direction, followed by comparison of the recovered local-frame nonlinear susceptibility tensor with that expected for Z-cut quartz based on crystal symmetry. Z-cut quartz was chosen as a model system for its well-characterized relationships between its unique, nonzero tensor elements, as dictated by its crystal class, D3. Furthermore, Z-cut quartz exhibits no birefringence for light propagating along the Z axis. The specific case of polarization phase modulation with postsample optics described in Polarization Modulation SHG Microscopy with Additional Postsample Optics is demonstrated experimentally here. The instrument configuration was adopted from a home-built nonlinear laser scanning microscope, as described in DeWalt et al. (43), and briefly summarized here.

The excitation was accomplished by a mode-locked Ti:sapphire laser (Spectra-Physics, Mountain View, CA) operating at 80 MHz with a pulse duration of 100 fs. A wavelength of 800 nm and average powers of ∼60 mW were used during data acquisition. Fast beam scanning was performed to avoid sample damage. The beam was passed through an EOM (Conoptics, Danbury, CT) rotated 45° from its fast axis. To correct for polarization changes induced by the beam path and optical components in the microscope, a Soleil-Babinet compensator (Thorlabs, Newton, NJ) was placed after the EOM. The beam was then focused onto the sample by a 10× 0.3 NA objective (Nikon, Melville, NY) and collected by a 10× 0.35 NA long-working-distance objective (Qioptiq, Waltham, MA). Fundamental light was separated from SHG using a dichroic mirror and directed through a horizontal polarizer and collected in transmitted direction by a photodiode (DET-10A; Thorlabs, Newton, NJ). The reflected SHG signal was passed through a zero-order quarter waveplate rotated 22.5° from its fast axis and then separated into its horizontal and vertical components with a Glan-Taylor polarizer and vertically and horizontally polarized SHG was detected by two separate photomultiplier tubes (H12310-40; Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan) with bandpass filters (model no. HQ 400/20M-2P; Chroma Technology, Bellows Falls, VT) and a colored glass KG3 filter to further reject the fundamental light. Signals from all detectors were digitized simultaneously using synchronized digitization (44) with PCI-Express digital oscilloscope cards (model no. ATS-9350; AlazarTech, Pointe-Claire, Quebec, Canada). Sets of polarization-dependent nonlinear optical Stokes ellipsometric microscopy images of Z-cut quartz were acquired for nine known rotation angles (ϕ) about the Z axis of quartz (−50°, −40°, −30°, −20°, −10°, 0°, 10°, 20°, 30°). Images were integrated to generate a set of 20 polarization-dependent SHG intensities and 10 polarization-dependent transmitted IR images for each rotation angle (10 input polarizations, three detectors).

Results and Discussion

As shown in Eq. 37, the phase of the polarization modulation is required for the analysis. A nonlinear fit of the experimental transmitted IR intensity as a function of phase delay value was used to recover the phase for each of 10 unique polarization states, corresponding to modulation at 8 MHz for an 80 MHz laser source. Subsequently, the polarization-dependent intensity profile was converted to the five polynomial coefficients. For Z-cut quartz, three nonzero tensor elements remain with the following local-frame relationships: for measurements where Z-cut quartz is probed along the z axis. From these relationships, it is clear that the three nonzero elements are all equal in magnitude, with and being opposite in sign to . For the specific case examined here, the threefold symmetry about the quartz Z axis demands that the refractive index be identical for all rotation angles about that axis, such that the matrix L simply reduces to a rescaled identity matrix. In the experimental configuration, where Z-cut quartz is probed along its crystallographic z axis, the out-of-plane tilt angle θ = 0° and azimuthal rotation angle ϕ and twist-angle ψ describe equivalent symmetry operations, effectively reducing J to have a dependence on ϕ only. The known rotation angles were used to generate the unique rotation matrix Jϕ, as outlined in Eq. 58.

Analysis of the polarization-dependent data set for Z-cut quartz was performed by linear fitting and matrix operations as described in Polarization Modulation SHG Microscopy with Additional Postsample Optics to generate polynomial coefficients and products. In the experiments described herein, a quarter waveplate (QWP) rotated to 22.5° was added before detection as an illustration of the incorporation of postsample polarization optics in the mathematical framework. The effect from the postsample waveplate can be expressed as a 2×2 complex valued Jones matrix, MQWP, where R is the rotation matrix for the QWP at 22.5°(θ):

| (61) |

To reduce the number of recovered parameters to two, and were assumed to be equal in the analysis, consistent with the requirements by the lattice symmetry. The recovered normalized experimental products of the two unique elements, and , are indicated in Table 1. The values for tensor element products and for individual tensor elements are reported as normalized unitless unit vectors. Nonlinear fitting to the products recovered normalized experimental values for and of 0.71 ± 0.09 and −0.69 ± 0.09, respectively. The values of and are predicted by theory to be equal and opposite in sign. The recovered experimental values are in close agreement with theoretical predictions, with differences in magnitude being attributed to residual uncertainties in the calculated phase angles of the EOM, imperfections in the cut of the Z-cut quartz, and/or subtle deviations of the assumption of plane polarized light after focusing through the low NA objective.

Table 1.

Recovered Normalized Experimental Products of Local-Frame Tensor for Z-Cut Quartz

| Relative Products of | |

|---|---|

| 0.55 ± 0.13 | |

| −0.48 ± 0.06 | |

| −0.52 ± 0.06 | |

| 0.45 ± 0.03 | |

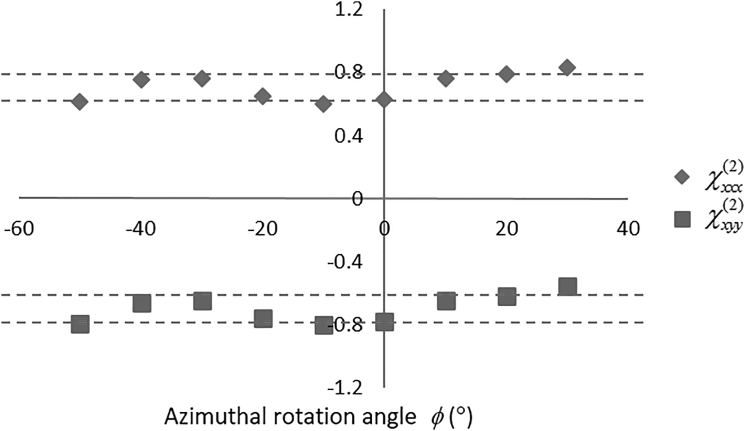

The observation of consistent values for the recovered local-frame tensor elements over many azimuthal rotation angles ϕ, as shown in Fig. 6, supports the reliability of the proposed mathematical framework for recovering local-frame tensors from laboratory-frame measurements. Both the polynomial/Fourier fitting coefficients described in Eq. 46 directly recovered from the measurements change quite substantially as ϕ is rotated. Nevertheless, combining these values with the known rotation angle ϕ recovered local-frame tensor elements in good agreement for all ϕ-angles investigated.

Figure 6.

The recovered normalized local tensor elements for Z-cut quartz at different azimuthal rotation angles, ϕ. The dashed lines represent the standard deviation of the recovered values.

The analysis of Z-cut quartz only included the azimuthal rotation angles ϕ while in principle the mathematical framework is applicable to ϕ, θ, and ψ for samples with different symmetry operations. It is worth noting that the effect of birefringence from Z-cut quartz is negligible at the probed configuration and is not included in the analysis. However, perturbations to the fundamental beam from sample birefringence can be addressed by including the Jones matrix describing the sample birefringence effect.

Conclusions

A unified theoretical framework is presented to unite a plethora of different polarization-dependent microscopy architectures for SHG microscopy. By extending the well-established Jones formalism to second-order nonlinear optics, this framework offers direct connection and comparison among multiple experimental architectures. Two steps are involved in the process: model-independent recovery of Jones tensors and the model-dependent local-frame tensor calculation. Analytical expressions were developed for four commonly employed polarization manipulation architectures, allowing for a high degree of flexibility in terms of instrumentation. Polarization-dependent SHG measurement with fast phase modulation using an EOM was performed on Z-cut quartz and the relative local-frame nonlinear susceptibility tensor for Z-cut quartz was calculated. The recovered result was in good agreement with the expected values dictated by the symmetry of Z-cut quartz.

The framework presented here can serve as a guideline for experiment design. As shown in the study of the select specific cases, each configuration allows access to unique combinations of related observables, with tradeoffs between information content and measurement complexity. For example, PIPO measurements provide an additional five observables relative to the 10 accessible from fixed optics configurations, but with additional required measurements. Alternatively, phase modulation platforms, such as modulating the relative phase delay between the vertical and horizontal components of light using an EOM, are compatible with high-speed modulation with corresponding opportunities for substantial reduction in 1/f noise and total measurement time.

Author Contributions

X.Y.D. was the primary article author, contributed to the mathematical framework described in the article, designed and performed the experiment, and analyzed data; E.L.D. contributed to the mathematical framework described in the article, designed and performed the experiment, and analyzed data; J.A.N. contributed to the mathematical framework described in the article; C.M.D. contributed to the mathematical framework described in the article; and G.J.S. advised in research design and developed the original mathematical framework described in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Jonathon Amy Facility for Chemical Instrumentation at Purdue University for their support in developing the data acquisition electronics used for the measurement of Z-cut quartz.

The authors acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health grants No. R01GM-103401 and No. R01GM-103910 the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Editor: Nathan Baker.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods and one figure are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)30214-4.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Fine S., Hansen W.P. Optical second harmonic generation in biological systems. Appl. Opt. 1971;10:2350–2353. doi: 10.1364/AO.10.002350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han M., Giese G., Bille J. Second harmonic generation imaging of collagen fibrils in cornea and sclera. Opt. Express. 2005;13:5791–5797. doi: 10.1364/opex.13.005791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai M.-R., Chiu Y.-W., Sun C.-K. Second-harmonic generation imaging of collagen fibers in myocardium for atrial fibrillation diagnosis. J. Biomed. Opt. 2010;15:026002. doi: 10.1117/1.3365943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zoumi A., Yeh A., Tromberg B.J. Imaging cells and extracellular matrix in vivo by using second-harmonic generation and two-photon excited fluorescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:11014–11019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172368799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campagnola P.J., Mohler W.H., Millard A.C. Second harmonic generation imaging of endogenous structural proteins. J. Biomed. Opt. 2003:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00292-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dombeck D.A., Kasischke K.A., Webb W.W. Uniform polarity microtubule assemblies imaged in native brain tissue by second-harmonic generation microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:7081–7086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0731953100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freund I., Deutsch M. Second-harmonic microscopy of biological tissue. Opt. Lett. 1986;11:94–96. doi: 10.1364/ol.11.000094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Theodossiou T.A., Thrasivoulou C., Becker D.L. Second harmonic generation confocal microscopy of collagen type I from rat tendon cryosections. Biophys. J. 2006;91:4665–4677. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.093740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeWalt E.L., Begue V.J., Simpson G.J. Polarization-resolved second-harmonic generation microscopy as a method to visualize protein-crystal domains. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2013;69:74–81. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912042503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plocinik R.M., Simpson G.J. Polarization characterization in surface second harmonic generation by nonlinear optical null ellipsometry. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2003;496:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoller P., Reiser K.M., Rubenchik A.M. Polarization-modulated second harmonic generation in collagen. Biophys. J. 2002;82:3330–3342. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75673-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su P.-J., Chen W.-L., Dong C.-Y. Determination of collagen nanostructure from second-order susceptibility tensor analysis. Biophys. J. 2011;100:2053–2062. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams R.M., Zipfel W.R., Webb W.W. Interpreting second-harmonic generation images of collagen I fibrils. Biophys. J. 2005;88:1377–1386. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tuer A.E., Krouglov S., Barzda V. Nonlinear optical properties of type I collagen fibers studied by polarization dependent second harmonic generation microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:12759–12769. doi: 10.1021/jp206308k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoller P., Celliers P.M., Rubenchik A.M. Quantitative second-harmonic generation microscopy in collagen. Appl. Opt. 2003;42:5209–5219. doi: 10.1364/ao.42.005209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Psilodimitrakopoulos S., Santos S.I., Loza-Alvarez P. In vivo, pixel-resolution mapping of thick filaments’ orientation in nonfibrillar muscle using polarization-sensitive second harmonic generation microscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2009;14:014001. doi: 10.1117/1.3059627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreaux L., Sandre O., Mertz J. Membrane imaging by second-harmonic generation microscopy. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B. 2000;17:1685–1694. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mansfield J.C., Winlove C.P., Matcher S.J. Collagen fiber arrangement in normal and diseased cartilage studied by polarization sensitive nonlinear microscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2008;4:044020. doi: 10.1117/1.2950318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campagnola P.J., Loew L.M. Second-harmonic imaging microscopy for visualizing biomolecular arrays in cells, tissues and organisms. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:1356–1360. doi: 10.1038/nbt894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoller P., Kim B.-M., Da Silva L.B. Polarization-dependent optical second-harmonic imaging of a rat-tail tendon. J. Biomed. Opt. 2002;7:205–214. doi: 10.1117/1.1431967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matteini P., Ratto F., Pini R. Photothermally induced disordered patterns of corneal collagen revealed by SHG imaging. Opt. Express. 2009;17:4868–4878. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.004868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golaraei A., Cisek R., Barzda V. Characterization of collagen in non-small cell lung carcinoma with second harmonic polarization microscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express. 2014;5:3562–3567. doi: 10.1364/BOE.5.003562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han Y., Hsu J., Potma E.O. Polarization-sensitive sum-frequency generation microscopy of collagen fibers. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:3356–3365. doi: 10.1021/jp511058b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heinz T., Tom H., Shen Y.R. Determination of molecular orientation of monolayer adsorbates by optical second-harmonic generation. Phys. Rev. A. 1983;28:1883–1885. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinz T.F., Loy M.M., Thompson W.A. Study of Si111 surfaces by optical second-harmonic generation: Reconstruction and surface phase transformation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1985;54:63–66. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.54.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen Y. Optical second harmonic generation at interfaces. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1989;40:327–350. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naujok R.R., Higgins D.A., Com R.M. Optical second-harmonic generation measurements of molecular adsorption and orientation at the liquid/liquid electrochemical interface. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1995;91:1411–1420. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang H.-F., Velarde L., Fu L. Quantitative sum-frequency generation vibrational spectroscopy of molecular surfaces and interfaces: lineshape, polarization, and orientation. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2015;66:189–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-040214-121322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishihara T., Ishiyama T., Morita A. Surface structure of methanol/water solutions via sum frequency orientational analysis and molecular dynamics simulation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015;119:9879–9889. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agrawal G., Pattanayak D. Gaussian beam propagation beyond the paraxial approximation. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1979;69:575–578. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pavone F.S., Campagnola P.J. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2013. Second Harmonic Generation Imaging. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones R.C. A new calculus for the treatment of optical systems. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1941;31:488–493. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drevillon B., Perrin J., Dalby J. Fast polarization modulated ellipsometer using a microprocessor system for digital Fourier analysis. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1982;53:969–977. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duboisset J., Aït-Belkacem D., Brasselet S. Generic model of the molecular orientational distribution probed by polarization-resolved second-harmonic generation. Phys. Rev. A. Am. Phys. Soc. 2012;85:043829. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan L., Ho J.Y., Kwok H.-S. Extended Jones matrix method for oblique incidence study of polarization gratings. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012;101:051107. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang T., Ruan Y., Sentenac A. Full-polarized tomographic diffraction microscopy achieves a resolution about one-fourth of the wavelength. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013;111:243904. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.243904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tuer A.E., Akens M.K., Barzda V. Hierarchical model of fibrillar collagen organization for interpreting the second-order susceptibility tensors in biological tissue. Biophys. J. 2012;103:2093–2105. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bordo V.G., Kato T. On the determination of molecular orientation from polarized imaging in second-harmonic microscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;118:4778–4780. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen Y.R. John Wiley; New York: 1984. The Principles of Nonlinear Optics. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boyd R.W. Academic Press; New York: 2003. Nonlinear Optics. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Munn R.W. Electric-dipole interactions in molecular crystals. Mol. Phys. 1988;64:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wortmann R., Bishop D.M. Effective polarizabilities and local field corrections for nonlinear optical experiments in condensed media. J. Chem. Phys. 1998;108:1001–1007. [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeWalt E.L., Sullivan S.Z., Simpson G.J. Polarization-modulated second harmonic generation ellipsometric microscopy at video rate. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:8448–8456. doi: 10.1021/ac502124v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sullivan S.Z., DeWalt E.L., Simpson G.J. Synchronous-digitization for video rate polarization modulated beam scanning second harmonic generation microscopy. Proc. SPIE. 2015;9330:93300A. doi: 10.1117/12.2079623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.