Summary

Objective

The objective of this study is to develop an algorithm to accurately identify children with severe early onset childhood obesity (ages 1–5.99 years) using structured and unstructured data from the electronic health record (EHR).

Introduction

Childhood obesity increases risk factors for cardiovascular morbidity and vascular disease. Accurate definition of a high precision phenotype through a standardize tool is critical to the success of large-scale genomic studies and validating rare monogenic variants causing severe early onset obesity.

Data and Methods

Rule based and machine learning based algorithms were developed using structured and unstructured data from two EHR databases from Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH) and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center (CCHMC). Exclusion criteria including medications or comorbid diagnoses were defined. Machine learning algorithms were developed using cross-site training and testing in addition to experimenting with natural language processing features.

Results

Precision was emphasized for a high fidelity cohort. The rule-based algorithm performed the best overall, 0.895 (CCHMC) and 0.770 (BCH). The best feature set for machine learning employed Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) concept unique identifiers (CUIs), ICD-9 codes, and RxNorm codes.

Conclusions

Detecting severe early childhood obesity is essential for the intervention potential in children at the highest long-term risk of developing comorbidities related to obesity and excluding patients with underlying pathological and non-syndromic causes of obesity assists in developing a high-precision cohort for genetic study. Further such phenotyping efforts inform future practical application in health care environments utilizing clinical decision support.

Keywords: Electronic health record, obesity, phenotype, machine learning, algorithm

Introduction

Childhood obesity is a threat to our population’s future health. The rapid rise in obesity portends an epidemic of chronic diseases like diabetes, hypertension with countless co-morbidities. The National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–12 has shown a prevalence of obesity at 16.9% amongst children between the ages of 2–19 years [1] with, severe obesity as the fastest growing sub-category [2]. Severe childhood obesity in children older than 24 months, equivalent to Class 2 obesity in adults is considered 120% of 95th percentile of body mass index (BMI) for age [2, 3]. There are varying estimates on the prevalence of severe childhood obesity. The NHANES data from 2011–2012 shows a prevalence of 5.9% across all ages and 1.9–2.6% in children between 2–5 years of age [2]. This represents a greater than200% increase from 1999 to 2012, with the highest rise in Hispanic females and black males [2]. In a study of 42,559 children between 3–5 years of age using the electronic health record (EHR), severe obesity was seen in 1.6% of the records, with the highest rates in Hispanic boys [4].

Childhood obesity increases the risk of adult adiposity and cardio-metabolic complications [5]. Children with BMI ≥ 99th percentile in 5th grade and those with a faster increase in BMI between the ages of 8–12 years have higher risk factors for cardiovascular morbidity and vascular disease [6–9]. Although little data exists for children younger than 6 years of age, it can be presumed that the risks predisposing to cardiovascular morbidity are magnified in children with earlier onset of severe obesity. Interventions for obesity have the greatest effect in the younger age group and those with severe obesity [10, 11]. Hence, early identification of young children with severe obesity presents an opportune moment for intervention.

Although there is a significant influence of the environment on obesity, genetic factors play an indisputable role. Twin studies have shown 40–80% heritability of various measures of obesity [12]. There is an increasing recognition of rare monogenic variants causing severe early onset obesity [13]. Some genetic causes such as leptin deficiency or Prader-Willi syndrome, though rare, may be amenable to treatment [14] and inform the societal attitude towards severe obesity [15]. The prevalence of variants causing monogenic obesity with complete or incomplete penetrance in the children with severe early onset obesity is largely unknown and will require genomic studies in large cohorts. Young children with severe obesity may be better suited for gene identification as environmental contributors to obesity (i.e., sedentary lifestyle, access to high calorie foods) may not be the driving factor or cause [16]. One of the challenges of performing such studies is the difficulty in identification and collection of large cohorts. Hospital and clinic records can provide an excellent source of data in young children as they have multiple health care encounters for routine care.

A growing number of studies have targeted the EHR for phenotype detection [10, 11, 17]. The eMERGE (electronic MEdical Record and GEnomic) network is currently exploring more than 40 EHR-based phenotypes [18–24]. The availability of automated BMI calculations and documentation in the EHR has made diagnosis of obesity more convenient and amenable to extraction [25]. Accurate definition of a phenotype is critical to the success of large-scale genomic studies [26] and the discrete BMI data alone will not yield a high-precision phenotype as many pathologic conditions can cause obesity. Additionally, errors in data entry in clinical records not designed for research may compromise the ability to obtain valid cohorts if identified using only structured EHR data. Developing a standardized tool that can accurately identify children with severe early onset obesity will open several unexplored avenues of research. The standardized tool for identification should be capable of using both structured data (e.g., height, weight, diagnoses and procedure codes) and unstructured data (e.g., physicians’ notes, discharge instructions, etc.).

Mining the unstructured EHR data using natural language processing (NLP) remains an important research task and includes challenges and benefits. The challenges are missing or inconsistent data, conflicting data over time, and specialized terminology or abbreviations [25, 27]. The benefits include a better understanding of disease profiles, improved research applications, and clinical care [28–30]. In this study we evaluate the application of machine learning and rule-based approaches in leveraging structured and unstructured data to develop an algorithm to identify young children (1–5.99 years) with severe obesity, an enriched group for detecting obesity-causing genetic variants. As the clinical definition of obesity is based on measurement, our tool is an exclusion-based algorithm, designed to filter out the patients with obesity caused by a co-morbid condition or medication use.

Data and Methods

Data was collected from the available EHR databases for patients from BCH (BCH) and CCHMC (CCHMC). BCH has been using a comprehensive EHR since 2006 (Cerner Corporation, Kansas City, MO) and CCHMC has utilized Epic since 2010 (Epic Systems, Verona, WI). Structured information (height, weight, demographic information, diagnosis codes (ICD-9) and medication orders) and unstructured data (clinical narrative notes) were extracted from the initial patient cohort. The Institutional Review Board at each of the hospitals approved this study.

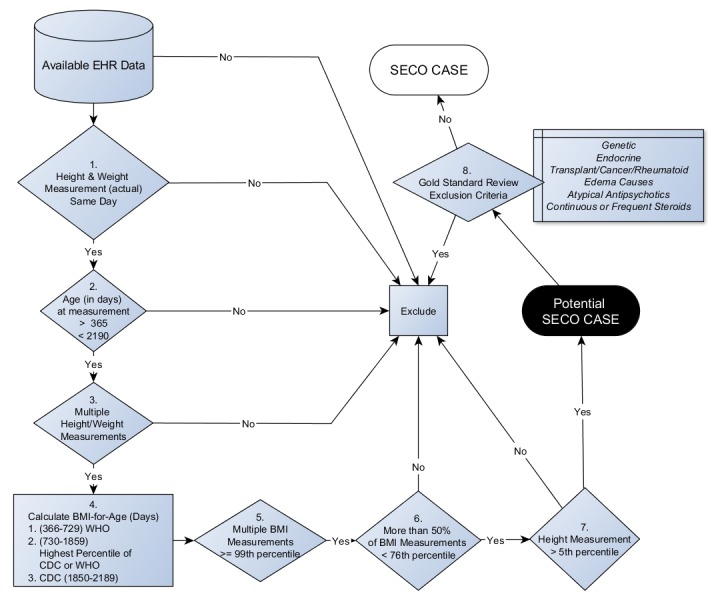

The initial cohort was identified by the availability of a height and weight measurement performed on the same day between the ages of 1–6 years (exclusive) in the EHR. Although there is no accepted clinical definition of obesity under the age of 2, we included children 1 year and age and up because early-onset obesity is defined as obesity before the age of 2; monogenic obesity syndromes typically manifest before the age of 2. We felt that obesity at this young age was not likely to be due to early feeding practices and more likely to be due to genetic influences. Based on the date of measurement, an age in months was computed to calculate a percentile BMI using the LMS (lambda mu sigma) criteria devised by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) for children over 24 months of age [31, 32]. The World Health Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards, developed with the WHO Multicenter Growth Reference Study in 2006 [33], are approved for use in children 0 to 2 years of age by the CDC. The WHO growth charts were created from a diverse multi-ethnic cohort of breast-fed infants and are thought to better represent more ideal infant growth patterns than CDC charts, which were developed from a cohort of both bottle-fed and breast-fed US infants. In older children, the definition of obesity using WHO growth charts is a BMI of +2 SD for age and sex. As with the CDC, WHO doesn’t have a clinical recommendation to evaluate BMI under the age of 2; however, we felt that the 99th%ile of BMI on the WHO charts was a reasonable surrogate to identify children who might have a genetic component to their obesity. Where the data from the two growth charts overlapped (age in days, 730–1856), we selected the higher of the two percentiles derived from each growth chart for inclusion. Morbid childhood obesity was defined as BMI greater than 99th percentile, an older definition for severe childhood obesity [34]. We chose this definition as both EHR systems provide raw calculations of BMI, and are unable to categorize BMI measurements as percentages over the 95th percentile. The detailed algorithm is in ► Figure 1. For the purposes of inclusion in the algorithm, at least two BMI measurements were required to be greater than or equal to the 99th percentile (► Figure 1, step 5) on different calendar days. If more than one measurement was available for a day, the first measurement of the day was considered. To avoid outliers and errors in measurement, no more than 50% of all available BMI measurements could be less than 75th percentile (► Figure 1, step 6). To avoid biologically implausible values of height, all qualifying height measurement were required to be greater than 5th percentile for age (► Figure 1, step 7).

Fig. 1.

SECO (Severe Early Childhood Obesity) Inclusion Algorithm

Gold Standard

After inclusion and outlier criteria were applied, 450 patients were randomly selected from 2,200 (CCHMC) and 200 from 3,675 (BCH) for gold standard chart review. During the chart review, the inclusion criteria were confirmed and additional exclusion criteria were considered (Step 8, ► Figure 1). The exclusion criteria list was developed by domain experts to exclude pathological conditions that could contribute to obesity, such as malignancy, neurological surgery, brain trauma, endocrine abnormalities etc. Patients receiving prolonged glucocorticoid were excluded. A patient was excluded if the EHR contained evidence of glucocorticoid treatment longer than 14 days, or three or more separate courses totaling more than 28 days in the six months prior to the measurement. A prescription of atypical anti-psychotic medications was also excluded due to their influence on body weight [35].

At CCHMC, two physicians from the Division of Endocrinology and one physician from the Division of Emergency Medicine performed the gold standard annotation. All the charts were double annotated after an initial triple coding of 80 patients for training. Discrepancies were adjudicated. At BCH, two physicians from the Division of Endocrinology performed double coding of 20 patients for training. Inter-annotator agreement (IAA) was measured in pair-wise F-measure (the harmonic mean of positive predictive value and sensitivity). For the training sets, the IAA averaged 89.5% at CCHMC, and was 90% at BCH. After training, the IAA at CCHMC averaged 98.6%. The remainder of the BCH gold standard was single annotated.

Automated Algorithms for SECO Detection

To develop an automated algorithm we experimented with rule based and machine learning methods. We compared it against a baseline performance, which was defined by the performance of the manual exclusion (gold standard) versus the potential SECO cases (► Figure 1). For the rule-based algorithm, we manually created a map of the pathological causes of obesity (exclusion criteria described above) to ICD-9 diagnosis codes. We generated patient vectors of all ICD-9 codes and removed those with the relevant exclusionary codes (► Table 1). We also excluded patients who met the criteria for medication exclusion. We evaluated the results based on the entire gold standard set described in the previous section.

Table 1.

Exclusion Criteria

| ICD-9 Codes | |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 Code | Description |

| 191.1 | Cancer |

| 244.9 | Hypothyroidism |

| 250.01 | Type 1 diabetes |

| 250.03 | Type 1 diabetes |

| 253.2 | Panhypopituitarism |

| 253.3 | Growth hormone deficiency |

| 255 | Cushing syndrome |

| 255.41 | Adrenal Insufficiency |

| 259.1 | Precocious puberty |

| 259.8 | Hypothalamic obesity |

| 277.89 | Histiocytosis |

| 428 | Congestive heart failure |

| 530.13 | Eosinophilic Esophagitis |

| 555.9 | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| 556.9 | Ulcerative colitis, unspecified |

| 581.9 | Nephrotic syndrome |

| 585.6 | End Stage Renal disease |

| 756.59 | Albright Hereditary Osteodystrophy/ Pseudohypoparathyroidism |

| 758 | Down Syndrome |

| 758.6 | Turner’s Syndrome |

| 759.81 | Prader-Willi Syndrome |

| 759.89 | Noonan’s Syndrome,Bardet-Biedl,Carpenter’s Syndrome,Alstrom Syndrome |

| 782.3 | Edema |

| 191* | Malignant neoplasm of brain |

| 201* | Hodgkin’s disease |

| 202* | Malignant neoplasms of lymphoid and hisiocytic tissue |

| 203* | Multiple myeloma and immunoproliferative neoplasm |

| 204* | Lymphoid leukemia |

| 205* | Myeloid leukemia |

| 206* | Monocytic leukemia |

| 207* | Other specified Leukemia |

| 208* | Leukemia of unspecified cell type |

| 714.3* | juvenile rheumatoid arthritis |

| 996.8* | Acute rejection |

| V42.0 | s/p kidney transplantation |

| V42.1 | s/p heart transplantation |

| V42.7 | s/p Liver transplantation |

| V42.81 | s/p Bone marrow transplantation |

| Medications | |

| Atypical Antipsychotics | |

| aripiprazole (Abilify) | |

| clozapine (Clozaril) | |

| olanzapine (Zyprexa) | |

| quetiapine (Seroquel) | |

| paliperidone (Invega) | |

| ziprasidone (Geodon) | |

| risperdal (risperidone) | |

| Glucocorticoids | |

* All codes in the ICD-9 range that begin with this number were used.

For the machine learning algorithms, the information from EHR data was aggregated and transformed into a single vector for each patient. The primary feature was Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) concept unique identifiers (CUIs), which represented clinical concepts in the patient’s EHR notes. The CUIs were extracted using Apache cTAKES [36] and converted into concept vectors. cTAKES implements a full stack of NLP modules including part-of-speech tagger, parsers, relation discovery modules, as well as attribute identification modules (such as negation, uncertainty, subject). It also employs a dictionary lookup algorithm with a sliding window to allow for term variations. For example, cTAKES identified two CUIs, C1510586 (for Autism Spectrum Disorder) and C0021390 (for inflammatory bowel disease), from the sentence “patient diagnosed with ASD and inflammatory bowel disease”, for which the CUIs became the vector representation. We partitioned the data into training, development and test (60%, 20%, 20%, respectively), developed the parameters of the machine learning algorithm on the development set and evaluated the results on the test set (held-out data). We experimented with the WEKA [37] implementation of support vector machines (SVM). To determine the most appropriate feature type combinations, we set up a series of machine learning experiments using ICD-9 diagnosis codes, UMLS semantic types (TUIs), RxNorm codes for medications and ngrams (single words and phrases up to three words in length). We optimized for feature type combinations and cost parameter value. We performed chi-square feature selection on the best performing feature type combination to avoid over-fitting.

We also experimented with maximizing precision, using Naïve Bayes (NB) algorithm in WEKA because the SVM implementation doesn’t provide a probability estimate for each prediction. The vector input for the NB experiment was identical to the SVM input, using default parameters for the algorithm.

Because one of the goals in developing a decision support tool is generalizability, we also conducted site experiments with training from one site and testing on the other site (e.g., training data from BCH and testing data from CCHMC) in addition to combining both site data for training and testing. The permutations of this experiment gave us nine different results with which to compare, not including the two classification methods. We reported the best results using positive predictive value, sensitivity and F-measure.

Results

In order to fairly compare the evaluation of rule and machine learning-based algorithms, 22 patients were excluded from CCHMC gold standard due to lack of provider documentation on the dates the height and weight were measured. The baseline accuracy is defined by comparing the gold standard against using BMI measurements only for case definition (Step 7, ► Figure 1). Of 428 patients in the CCHMC evaluation set, 320 were judged to be cases for severe early childhood obesity (74.8%). At BCH the baseline result was 76.5% (153/200). To restate the definition of the baseline, 25.2% of the CCHMC patients who were judged to be potential SECO cases (► Figure 1), were excluded in the chart review process, on the bases of medication or comorbid diagnosis.

The rule-based algorithm was run on the patients who were selected as potential cases. Any patient who had an exclusionary ICD-9 diagnosis was considered a non-case. Also, any patient who met the medication exclusion criteria was considered non-case. The rule-based algorithm at CCHMC performed better for precision than at BCH (► Table 2). The evaluation of the rule-based algorithm is presented in ► Table 2 with the baseline results. Sensitivity is not available for the baseline results because patients were not selected from the EHR if they did not meet BMI measurements threshold described above and depicted in ► Figure 1. Vanderbilt University and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia validated the rule-based algorithm at their institutions, measuring PPV of 0.987 and 0.96, respectively. They evaluated the results of the algorithm by manual chart review of a random selection of 50 predicted cases at each institution. The machine learning algorithm was not validated at other institutions because the performance of the rule-based algorithm was superior at the primary institutions.

Table 2.

Rule-based Algorithm Results

| Corpus | PPV1 | Sensitivity | F-Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCHMC-BASELINE | 0.748 | N/A | N/A |

| BCH-BASELINE | 0.765 | N/A | N/A |

| CCHMC-RULE | 0.895 | 0.72 | 0.798 |

| BCH RULE | 0.770 | 0.76 | 0.765 |

For the machine learning algorithm we presented the best performing feature type combination sets, using the CCHMC training and development sets and optimizing for cost parameter value, in increments of 0.1 from 0.1 to 20 (► Table 3). Several feature type combinations did not have any performance gain over the default cost value (1.0) (indicated by ‘n/a’ in the optimized cost column in ► Table 3. Where multiple cost values had similar results, the lowest optimized cost is in italics. The top performance for precision used CUI codes only. However, there was very little difference in performance between using CUIs only and adding ICD-9 or ICD-9 plus RxNorm codes. For our feature type combination we used cui+icd9+rx because it gave us better sensitivity without sacrificing precision.

Table 3.

Feature Type Combination and Cost Optimization

| Feature Set | P | R | F | Optimized Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cui | 0.832 | 0.866 | 0.848 | 0.8 |

| cui+icd9 | 0.83 | 0.853 | 0.841 | 0.9 |

| cui+icd9+rx | 0.83 | 0.869 | 0.849 | 0.4 |

| cui+ngram | 0.807 | 0.953 | 0.874 | n/a |

| cui+ngram+icd9 | 0.807 | 0.953 | 0.874 | n/a |

| cui+ngram+icd9+rx | 0.807 | 0.953 | 0.874 | n/a |

| cui+ngram+rx | 0.807 | 0.953 | 0.874 | n/a |

| cui+rx | 0.823 | 0.872 | 0.847 | 0.4 |

| Icd9 | 0.813 | 0.853 | 0.832 | 0.2 |

| Icd9+rx | 0.823 | 0.972 | 0.891 | 0.1 |

| ngram | 0.808 | 0.959 | 0.877 | n/a |

| ngram+icd9 | 0.808 | 0.959 | 0.877 | n/a |

| ngram+icd9+rx | 0.806 | 0.959 | 0.876 | n/a |

| ngram+rx | 0.804 | 0.959 | 0.875 | n/a |

| rx | 0.806 | 0.95 | 0.872 | 0.4 |

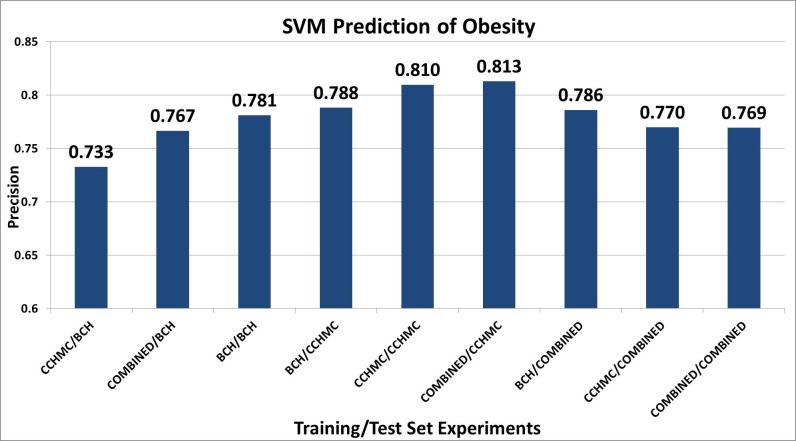

Automated feature selection was performed on the cui+icd9+rx feature type combination and the number of features were trimmed based on sorting the features by respective chi square values. We experimented with feature sizes from 40–200, in increments of 10. At 100 features, the precision for all the combined training set experiments converged and no more significant improvement was seen. We report the results on the best performing algorithm (SVM) and parameters on the held-out test set. ► Figure 2 demonstrates the results of the SVM experiments.

Fig. 2.

Machine Learning Prediction Results: SVM (Support Vector Machines), Training set experiments: First site listed is the training set, second site listed is the test set.

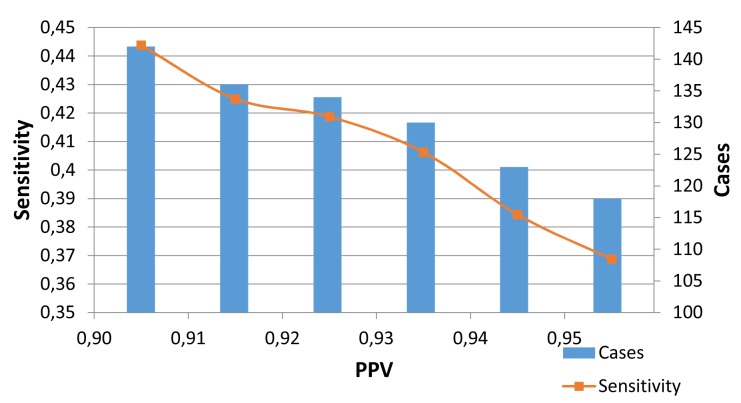

In ► Figure 3, we present the results of maximizing the positive predictive value (PPV, or Precision). We used a threshold file, created in WEKA output of NB algorithm, which contained the probability value for each patient prediction. Then using an interpolation package in R (38), we estimated the corresponding sensitivity, given a target value for PPV. ► Figure 3 illustrates the loss of predicted cases of obesity, given a target value of PPV. Changing the target PPV from 0.90 to 0.95, there is an estimated loss of 24 cases (to 118).

Fig. 3.

Machine Learning Results (Naïve Bayes) Optimizing the threshold for target of PPV (positive predictive value)

Discussion

The clinical definition of obesity is based on structured data (height and weight); however, to capture a group ideal for identification of obesity-causing genetic variants, it is necessary to exclude those with potential secondary obesity (obesity due to another condition). We developed an exclusionary algorithm, based on the available EHR information, to determine if a patient between the ages of 1–5.99 years met the definition of severe early childhood obesity. The utility of this algorithm is two-fold: first, detecting severe early childhood obesity is essential for the intervention potential in children at the highest long-term risk of developing comorbidities related to obesity; second, the avoidance of false positive cases for patients with pathological causes of obesity assists in developing a high-precision cohort for genetic study. The concordant results between the two study sites, CCHMC and BCH, (74.8% vs. 76.5%, respectively) indicates the similarity of the patient sets as well as the portability and generalizability of the algorithm. Since this study is a two-site test, and the aims of eMERGE include collaborative research, the true measure of generalizability is training the algorithm on one site’s data and examining the results of the other site testing data. [e.g., train: CCHMC, test: BCH]. The results in ► Figure 2 demonstrate that the SVM combined training set performed best on the CCHMC test set (0.813 PPV). Training on BCH data resulted in a very similar result, regardless of test data (BCH: 0.781 vs. CCHMC: 0.788 PPV). However, training on CCHMC data and testing on BCH data demonstrates less compatibility (0.733 PPV). The rule based algorithm performed better than machine learning algorithms on CCHMC test data set (0.895 vs. 0.813, respectively) and similarly on the BCH test data set (0.770 vs. 0.767).

The experiments started with a patient population that was initially selected for obesity based upon the measurement data. Thus, the algorithms developed can be considered to evaluate the exclusion or non-exclusion of patients from SECO case based upon pathological and/or medical causes of obesity. The focus of the methods evaluation was positive predictive value (PPV) because the goal of eMERGE study is genomic discovery of variants associated with phenotypes. Thus, a strong PPV, or precision is preferred.

In addition to discovery, an algorithm with a strong PPV contributes to an evidence-base for identifying early childhood obesity, an important step for prevention and treatment that can be enabled in automated electronic health data environments using clinical decision support systems (CDSS). As an evolving system, variations in operational definitions exist. A recent scientific review and meta-analysis examining outcomes using CDSS in randomized controlled trials operationally defined CDSS as an information system aimed to support clinical-decision making, linking patient-specific information in the EHR with evidence-based knowledge to generate case-specific guidance messages through a rule- or algorithm-based software and identified moderate improvements in morbidity outcomes but no pediatric studies were included [39]. More recently, promising improvements in reducing elementary-age child obesity risk were observed in a clinical effectiveness trial using CDSS in primary care [40]. This clinical decision support intervention study demonstrated the feasibility and utility using patient information to reliably implement clinical guidelines and educational messages however the information system lacked an algorithm with strong PPV to identify children most at risk. Future work may examine the utility of combining clinical guidelines and educational messages with an algorithm that precisely identifies children early in life, when obesity risk is most likely amendable to prevention and treatment. Such efforts can inform future practical application in health care environments utilizing the EHR and CDSS, functionalities and features that have been widely adopted and aligned with the Federal Health IT Strategic Plan, 2015–2020.

The feature type combination experiments are useful both specifically (for the current task) and generally for machine learning classification. Specifically, the rule-based algorithm eliminates comorbidities which can be represented by EHR ICD-9 codes and CUIs from the text (if not identified by ICD-9 codes). CUIs provide a higher level of abstraction than ngrams; the noise introduced by ngram features is evident in the drop in precision (► Table 3). However, it is reasonable that the rule-based method, which solely focuses on ICD-9 diagnosis codes and medications would perform better than the machine learning algorithm with semantic extraction from clinical notes. Sufficient noise may exist in the clinical notes is not related to the inclusion or exclusion of cases. In error analysis, comparing the clinical notes between each site, a low number of overlapping CUI features were present. Only 43% of the CUI features of both sites were common, before feature selection, indicating a high degree of unique terms, phrases or concepts among the notes of each site.

The Naïve Bayes PPV threshold experiments (► Figure 3 and ► Figure 4) demonstrate the effect of placing a high PPV target on the size of an intended cohort. Researchers can eliminate most of the false positives in a cohort, if they are willing to accept a smaller sample size. While the rule-based algorithm achieved a better balance between PPV and recall, thresholds can be utilized in machine learning algorithm implementations.

Further work is needed to maximize the utility and reduce the noise of the natural language in each site’s notes in order to improve the machine-learning algorithm.

Conclusion

We developed rule based and machine-learning based algorithms to identify severe early childhood obesity cases in young children for the purpose of genetic study and identification of those most likely to benefit from prevention and treatment interventions. We demonstrated that the rule-based exclusion algorithm performed better than the machine-learning algorithm. The benefit of using a machine-learning algorithm is flexibility in balancing PPV and sensitivity. In addition, machine-learning enables combining different feature types to demonstrate a more inclusive picture of the patient data. Both algorithms enabled generalizability between two different tertiary pediatric medical institutions. The algorithms filtered out the patients who were obese due to a co-morbid condition or medication use, in order to provide a high precision cohort for genetic study in the eMERGE network. Using this high fidelity cohort has a significant potential for genetic study and translation into clinical intervention trials.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Pei Chen for his consultation and support in running cTAKES.

Funding Statement

Funding All phases of this study were supported by United States National Institutes of Health (U1 1U01HG006828–01) as part of the Electronic Medical Record and Genomics project (eMERGE), NIH-NIDDK grant T32DK007699, K12DK094721 and Nutrition and Obesity Research Center at Harvard (P30-DK040561), as well as institutional funding from CCHMC, BCH, Vanderbilt University, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Geisinger Health System.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement

GS is on the Advisory Board of Wired Informatics which provides services and products for clinical NLP applications. The other authors have no competing interests relevant to this article to disclose.

Protection of Human Subjects

The study was performed in compliance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, and was reviewed by the respective Institutional Review Boards of CCHMC, BCH, Vanderbilt University, and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA 2014; 311(8):806–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skinner A, Skelton J. Prevalence and trends in obesity and severe obesity among children in the United States, 1999–2012. JAMA Pediatr 2014; 168(6):561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flegal K, Wei R. Characterizing extreme values of body mass index–for-age by using the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts. Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 90: 1314–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lo JC, Maring B, Chandra M, Daniels SR, Sinaiko A, Daley MF, Sherwood NE, Kharbanda EO, Parker ED, Adams KF, Prineas RJ, Magid DJ, O’Connor PJ, Greenspan LC. Prevalence of obesity and extreme obesity in children aged 3–5 years. Pediatr Obes 2014; 9(3):167–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright CM, Parker L, Lamont D, Craft AW. Implications of childhood obesity for adult health: findings from thousand families cohort study. BMJ 2001; 323(7324):1280–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freedman DS, Mei Z, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS, Dietz WH. Cardiovascular risk factors and excess adiposity among overweight children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Pediatr 2007; 150(1):12–17.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ice CL, Murphy E, Cottrell L, Neal WA. Morbidly obese diagnosis as an indicator of cardiovascular disease risk in children: results from the CARDIAC Project. Int J Pediatr Obes 2011; 6(2):113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imai CM, Gunnarsdottir I, Gudnason V, Aspelund T, Birgisdottir BE, Thorsdottir I, Halldorsson TI. Faster increase in body mass index between ages 8 and 13 is associated with risk factors for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2014; 24: 730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo JC, Chandra M, Sinaiko A, Daniels SR, Prineas RJ, Maring B, Parker ED, Sherwood NE, Daley MF, Kharbanda EO, Adams KF, Magid DJ, O’Connor PJ, Greenspan LC. Severe obesity in children: prevalence, persistence and relation to hypertension. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2014; 2014(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohane IS. Using electronic health records to drive discovery in disease genomics. Nat Rev Genet 2011; 12(6):417–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denny JC. Chapter 13: Mining electronic health records in the genomics era. PLoS Comput Biol 2012; 8(12):e1002823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Min J, Chiu DT, Wang Y. Variation in the heritability of body mass index based on diverse twin studies: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2013. doi:10.1111/obr.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barsh GS, Farooqi IS, O’Rahilly S. Genetics of body-weight regulation. Nature 2000; 404(6778):644–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farooqi IS, Jebb SA, G L, Lawrence E, Cheetham CH, Prentice A, Hughes I, McCamish M, O’Rahilly S. Effects of Recombinant Leptin Therapy in a Child with Congenital Leptin Deficiency. N Engl J Med 1999; 341(12):879–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Rahilly S, Farooqi IS. Human obesity: a heritable neurobehavioral disorder that is highly sensitive to environmental conditions. Diabetes 2008; 57(11):2905–2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Melanson EL. Genetic and environmental contributions to obesity. Med Clin North Am 2000; 84(2):333–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shivade C, Raghavan P, Fosler-Lussier E, Embi PJ, Elhadad N, Johnson SB, Lai AM. A review of approaches to identifying patient phenotype cohorts using electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2014; 21(2):221–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denny JC, Crawford DC, Ritchie MD, Bielinski SJ, Basford MA, Bradford Y, Chai HS, Bastarache L, Zuvich R, Peissig P, Carrell D, Ramirez AH, Pathak J, Wilke RA, Rasmussen L, Wang X, Pacheco JA, Kho AN, Hayes MG, Weston N, Matsumoto M, Kopp PA, Newton KM, Jarvik G P, Li R, Manolio TA, Kullo IJ, Chute CG, Chisholm RL, Larson EB, McCarty CA, Masys DR, Roden DM, de Andrade M. Variants near FOXE1 are associated with hypothyroidism and other thyroid conditions: using electronic medical records for genome- and phenome-wide studies. Am J Hum Genet 2011; 89(4):529–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kho AN, Hayes MG, Rasmussen-Torvik L, Pacheco JA, Thompson WK, Armstrong LL, Denny JC, Peissig PL, Miller AW, Wei W-Q, Bielinski SJ, Chute CG, Leibson CL, Jarvik GP, Crosslin DR, Carlson CS, Newton KM, Wolf WA, Chisholm RL, Lowe WL. Use of diverse electronic medical record systems to identify genetic risk for type 2 diabetes within a genome-wide association study. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012; 19(2):212–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kullo IJ, Fan J, Pathak J, Savova GK, Ali Z, Chute CG. Leveraging informatics for genetic studies: use of the electronic medical record to enable a genome-wide association study of peripheral arterial disease. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2010; 17(5):568–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newton KM, Peissig PL, Kho AN, Bielinski SJ, Berg RL, Choudhary V, Basford M, Chute CG, Kullo IJ, Li R, Pacheco JA, Rasmussen L V, Spangler L, Denny JC. Validation of electronic medical record-based phenotyping algorithms: results and lessons learned from the eMERGE network. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013; 20(e1):e147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pathak J, Kho AN, Denny JC. Electronic health records-driven phenotyping: challenges, recent advances, and perspectives. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013; 20(e2):e206–e211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peissig PL, Rasmussen L V, Berg RL, Linneman JG, McCarty CA, Waudby C, Chen L, Denny JC, Wilke RA, Pathak J, Carrell D, Kho AN, Starren JB. Importance of multi-modal approaches to effectively identify cataract cases from electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012; 19(2):225–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schildcrout JS, Basford MA, Pulley JM, Masys DR, Roden DM, Wang D, Chute CG, Kullo IJ, Carrell D, Peissig P, Kho A, Denny JC. An analytical approach to characterize morbidity profile dissimilarity between distinct cohorts using electronic medical records. J Biomed Inform 2010; 43(6):914–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bailey LC, Milov DE, Kelleher K, Kahn MG, Del Beccaro M, Yu F, Richards T, Forrest CB. Multi-Institutional Sharing of Electronic Health Record Data to Assess Childhood Obesity. PLoS One 2013; 8(6):e66192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plenge RM, Bridges SL, Huizinga TWJ, Criswell LA, Gregersen PK. Recommendations for publication of genetic association studies in Arthritis & Rheumatism. Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63(10):2839–2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rea S, Pathak J, Savova G, Oniki TA, Westberg L, Beebe CE, Tao C, Parker CG, Haug PJ, Huff SM, Chute CG. Building a robust, scalable and standards-driven infrastructure for secondary use of EHR data: the SHARPn project. J Biomed Inform 2012; 45(4):763–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen PB, Jensen LJ, Brunak S. Mining electronic health records: towards better research applications and clinical care. Nat Rev Genet 2012; 13(6):395–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manion FJ, Harris MR, Buyuktur AG, Clark PM, An LC, Hanauer DA. Leveraging EHR data for outcomes and comparative effectiveness research in oncology. Curr Oncol Rep 2012; 14(6):494–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warrer P, Hansen EH, Juhl-Jensen L, Aagaard L. Using text-mining techniques in electronic patient records to identify ADRs from medicine use. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012; 73(5):674–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Selected percentiles and LMS Parameters. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flegal K, Cole T. Construction of LMS parameters for the centers for disease control and prevention 2,000 growth charts. Natl Health Stat Report 2013; (63): 1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization: Child Growth Standards. Available at: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/bmi_for_age/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skelton J a, Cook SR, Auinger P, Klein JD, Barlow SE. Prevalence and trends of severe obesity among US children and adolescents. Acad Pediatr 2009; 9(5):322–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jensen GL. Drug-induced hyperphagia: what can we learn from psychiatric medications? JPEN. J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2008; 32(5):578–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savova GK, Coden AR, Sominsky IL, Johnson R, Ogren P V, de Groen PC, Chute CG. Word sense disambiguation across two domains: biomedical literature and clinical notes. J Biomed Inform 2008; 41(6):1088–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hall M, Frank E, Holmes G, Pfahringer B, Reutemann P WI. The WEKA data mining software: an update. ACM SIGKDD Explor Newsl 2009; 11(1):10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moja L, Kwag KH, Lytras T, Bertizzolo L, Brandt L, Pecoraro V, Rigon G, Vaona A, Ruggiero F, Mangia M, Iorio A, Kunnamo I, Bonovas S. Effectiveness of clinical decision support systems linked to electronic health records: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 2014; 104: e12-e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taveras EM, Marschall R, Kleinman KP, Gillman M W, Hacker K, Horan CM, Smith RL, Price S, Sharifi M, Rifas-Shiman SL, Simon SR. Comparative effectiveness of childhood obesity interventions in pediatric primary care: a cluster-randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 2015; 169(6): 535-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]