Abstract

Context:

Though common, depressive disorders often remain undetected in late life.

Aim:

To examine the usefulness of Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) for identifying depression among older people.

Settings and Design:

Community resident older people (aged 65 years or more), were evaluated by clinicians trained in psychiatry, as part of a cross-sectional study of late-life depression. Assessments were done in the community.

Methods and Material:

The participants were assigned ICD-10 diagnoses and assessed using Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and CES-D. A short version of CES-D with 10 items, translated to the local language Malayalam, was used.

Statistical Analysis:

The sensitivity and specificity of CES-D was evaluated against ICD-10 clinical diagnosis of depression. The correlation of CES-D and MADRS was assessed using Pearson correlation coefficient.

Results:

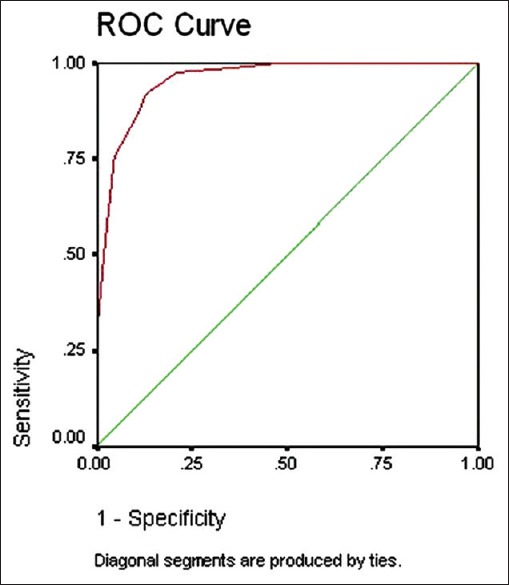

220 consenting adults from 3 wards of the Panchayath were assessed. On analysis of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve of CES-D scores in relation to clinical diagnosis, the large Area Under Curve (AUC) showed efficient screening and a cut off score of 4 in CES-D had a sensitivity of 97.7% and a specificity of 79.1% for depression. There was also good correlation between the MADRS and CES-D scores (0.838).

Conclusion:

CES-D is a short simple scale which can be used by health care professionals for detecting depression in older people in primary care settings.

Key words: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, community-resident elderly, depression, screening

INTRODUCTION

Mental health problems, especially depression, is common in late life. It has a negative effect on the quality of life of the individual and is associated with increased risk of mortality. Community-based studies from India have reported variable prevalence rates.[1,2,3,4] We recently reported a prevalence of 39.1% for depressive disorder in a rural community.[5] A recent review article concluded that depression is quite common in community-resident older people in India.[6] Early diagnosis of depression is important for effective intervention. Brief screening instruments can help detect late-life depression in community and primary care settings.

Among many depression-rating scales available, only a few have been validated in the elderly. Depression in the elderly presents unique problems related to cognition, sleep, somatic symptoms etc., which needs to be considered during the development of a screening instrument.[7] We wanted to test the usefulness of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), a commonly used screening test, for identifying depressive symptoms in the general population.[8,9] We used the short 10-item version which has been validated in different populations.[10,11] We report the usefulness of this scale in screening for depression in a community sample of older people.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The present study was a part of a larger ongoing project, jointly undertaken by the Government Medical College, Thrissur and a local Non Governmental Organization.[12] The study was done at Thalikulam Grama Panchayat, which is the rural administrative unit of the local self-government in Thrissur, Kerala. People above the age of 65 years were identified from an earlier health survey. All residents from the first three wards of the Panchayat were invited to participate in the study. Clinicians trained in psychiatry interviewed subjects at their homes or in the neighborhood. The following instruments were used for assessments: (1) Structured pro forma to assess sociodemographic characteristics and medical history, (2) symptom checklist based on the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) research diagnostic criteria for depression, (3) Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), (4) CES-D. Cases were categorized to mild depression with or without somatic syndrome, moderate depression with or without somatic syndrome, and severe depression with or without psychotic symptoms as per the ICD-10.[13]

RESULTS

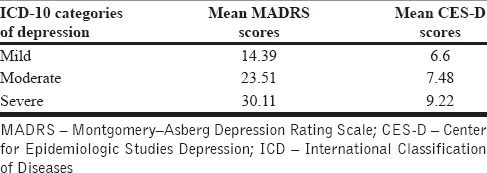

We invited 275 older people from three wards 1, 2, and 3 of the Panchayat. A total of 220 subjects consented. We have reported a prevalence of 39.1% (95% confidence interval 32.6–45.9) for syndromal depression in this sample when assessed by clinicians trained in psychiatry.[5] The mean CES-D was 6.6, 7.48, and 9.22 for mild, moderate, and severe depression, respectively. The sensitivity and specificity of CES-D were calculated using ICD-10 clinical diagnosis of depression as the gold standard.

A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was attained by plotting sensitivity against specificity for all scores of CES-D in relation to ICD-10 diagnosis for depressive symptoms [Figure 1]. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) represents the degree of correct classification with the screening tool, and thus, a larger AUC means more efficient screening. On analysis of the ROC curve, it was found that for a cutoff score of 3.5; the sensitivity was 0.98, and specificity was 0.79. Hence, those subjects who score 4 or above are probable cases with significant depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in relation to clinical diagnosis of depression

We also analyzed the correlation between MADRS and CES-D and a significantly high correlation of 0.84 was found between the two scores [Table 1].

Table 1.

Mean Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

DISCUSSION

We used a short 10-item version of CES-D. This is a short, simple scale and can be easily administered by healthcare professionals in primary care settings. The diagnosis of depression was made in the community by clinicians trained in psychiatry who used a symptom checklist based on ICD-10 research criteria for diagnosis of depression. This is as close to the gold standard for diagnosing depression in a community setting as possible and one of the strengths of our study. One major limitation of most Indian studies is their reliance on screening tools used by nonpsychiatrists alone while studying the prevalence of depression.[6] The cutoff score of CES-D for optimum sensitivity and specificity obtained is 4 which is similar to that of other studies.[14] We also found a significant correlation of between CES-D and MADRS (Pearson coefficient of correlation = 0.84). This 10-item CES-D, which is shorter than the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale, will help to enable community outreach services to identify and manage late-life depression.

In this study, clinicians trained in psychiatry had administered CES-D along with other instruments; thus, we cannot rule out rater bias. This is the major limitation of this study. However, we had instructed the clinicians to read out the questions verbatim and rate the responses of CES-D to all subjects in the same manner. We need to establish the screening property of CES-D when primary care doctors use this in primary care settings and health workers in community settings. We propose to do that in future studies.

CONCLUSION

Community resident older people are more likely to get in touch with the community health workers than mental health professionals, especially in resource limited settings.[15] Availability of a simple, short scale in the local language would lead to better identification of late life depression in these settings.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rajkumar AP, Thangadurai P, Senthilkumar P, Gayathri K, Prince M, Jacob KS. Nature, prevalence and factors associated with depression among the elderly in a rural South Indian community. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:372–8. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209008527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sengupta P, Benjamin AI. Prevalence of depression and associated risk factors among the elderly in urban and rural field practice areas of a tertiary care institution in Ludhiana. Indian J Public Health. 2015;59:3–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.152845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seby K, Chaudhury S, Chakraborty R. Prevalence of psychiatric and physical morbidity in an urban geriatric population. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53:121–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.82535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh AP, Kumar KL, Reddy CM. Psychiatric morbidity in geriatric population in old age homes and community: A comparative study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34:39–43. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.96157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakulan A, Sumesh TP, Kumar S, Rejani PP, Shaji KS. Prevalence and risk factors for depression among community resident older people in Kerala. Indian J Psychiatry. 2015;57:262–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.166640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grover S, Malhotra N. Depression in elderly: A review of Indian research. J Geriatr Ment Health. 2015;2:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 1982. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts RE, Vernon SW. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Its use in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:41–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang K, Weng L. Screening for depressive symptoms among older adults in Taiwan: Cut-off of a short form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. Health. 2013;5:588–94. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asokan N, Praveenlal K, Shaji KS. Evidence informed community healthcare in developing countries: Is there a role for tertiary care specialists? Natl J Community Med. 2011;2:496–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva: WHO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: Criterion validity of the 10-item center for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D) Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1701–4. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saraceno B, van Ommeren M, Batniji R, Cohen A, Gureje O, Mahoney J, et al. Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370:1164–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61263-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]