Abstract

Essentials.

Effect of plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)‐1 on plague and its Y. pestis cleavage is unknown.

An intranasal mouse model of infection was used to determine the role of PAI‐1 in pneumonic plague.

PAI‐1 is cleaved and inactivated by the Pla protease of Y. pestis in the lung airspace.

PAI‐1 impacts both bacterial outgrowth and the immune response to respiratory Y. pestis infection.

Click to hear Dr Bock discuss pathogen activators of plasminogen.

Summary

Background

The hemostatic regulator plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 (PAI‐1) inactivates endogenous plasminogen activators and aids in the immune response to bacterial infection. Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of plague, produces the Pla protease, a virulence factor that is required during plague. However, the specific hemostatic proteins cleaved by Pla in vivo that contribute to pathogenesis have not yet been fully elucidated.

Objectives

To determine whether PAI‐1 is cleaved by the Pla protease during pneumonic plague, and to define the impact of PAI‐1 on Y. pestis respiratory infection in the presence or absence of Pla.

Methods

An intranasal mouse model of pneumonic plague was used to assess the levels of total and active PAI‐1 in the lung airspace, and the impact of PAI‐1 deficiency on bacterial pathogenesis, the host immune response and plasmin generation following infection with wild‐type or ∆pla Y. pestis.

Results

We found that Y. pestis cleaves and inactivates PAI‐1 in the lungs in a Pla‐dependent manner. The loss of PAI‐1 enhances Y. pestis outgrowth in the absence of Pla, and is associated with increased conversion of plasminogen to plasmin. Furthermore, we found that PAI‐1 regulates immune cell recruitment, cytokine production and tissue permeability during pneumonic plague.

Conclusions

Our data demonstrate that PAI‐1 is an in vivo target of the Pla protease in the lungs, and that PAI‐1 is a key regulator of the pulmonary innate immune response. We conclude that the inactivation of PAI‐1 by Y. pestis alters the host environment to promote virulence during pneumonic plague.

Keywords: fibrinolysis, inflammation, plague, plasminogen, pneumonia

Introduction

The induction of fibrinolysis is tightly regulated to maintain vascular homeostasis and to prevent uncontrolled clot lysis 1. Tissue‐bound and soluble activators, including tissue‐type plasminogen activator (t‐PA) and urokinase plasminogen activator (u‐PA), mediate the conversion of the circulating zymogen plasminogen into its active serine protease form, plasmin. As an essential component of the fibrinolytic system, plasmin degrades fibrin clots, and has additional biological activities related to tissue remodeling, cell migration, and inflammation 2. However, uncontrolled plasmin activity can result in bleeding disorders and tissue damage; therefore, the inhibitors α2‐antiplasmin (A2AP) and α2‐macroglobulin also contribute to the hemostatic balance and regulate fibrinolysis by binding and inactivating free plasmin 3.

To regulate the generation of plasmin, the serine protease inhibitor plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 (PAI‐1) prevents the conversion of plasminogen into plasmin via binding of both t‐PA and u‐PA 4. PAI‐1 also has additional activities that are independent of its serpin activity, including the regulation of inflammation via immune cell migration, binding to cell surface receptors, with subsequent activation of intracellular signaling cascades, and effects on cytokine production 5, 6, 7. The expression and level of PAI‐1 in various tissues are increased in response to infection and injury; however, PAI‐1 shows a relatively short half‐life in circulation, but is stabilized by binding to the host protein vitronectin 8. Dysregulation of PAI‐1 levels or activity has been implicated in numerous disease states, including cancer metastasis 9, organ fibrosis 5, atherosclerosis, and myocardial infarction 10. PAI‐1 participates in the host response to multiple microbial infections, including those caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa 11, Klebsiella pneumoniae 12, Streptococcus pneumoniae 13, Burkholderia pseudomallei 14, and Haemophilus influenzae 15. In these studies, PAI‐1‐deficient mice were used in models of bacterial pneumonia to demonstrate that PAI‐1 is protective by inducing proinflammatory cytokine production and subsequent neutrophil recruitment to the sites of infection.

Consequently, multiple bacterial pathogens have evolved mechanisms to exploit or usurp host fibrinolysis 16, 17, 18, 19, 20. Yersinia pestis is the causative agent of bubonic, pneumonic and septicemic plague 21. Y. pestis produces the outer membrane omptin family aspartate protease known as Pla 22, 23, which enhances virulence in mouse models of pneumonic and bubonic plague 24, 25, 26. Pla is required for the outgrowth of Y. pestis during respiratory infection and for the development of a purulent, multifocal severe exudative bronchopneumonia that is the hallmark of pneumonic plague 27. Pla is a potent activator of host plasminogen, and cleaves the zymogen at the same residues recognized by endogenous plasminogen activators (PAs) 23, 24, 28. Other host substrates associated with the fibrinolytic system have also been identified and characterized in vitro as potential Pla targets, including A2AP, thrombin‐activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor, and PAI‐1 29, 30, 31. Thus, it has been hypothesized that, through the activities of Pla, Y. pestis enhances fibrinolysis by targeting multiple regulatory points of the host hemostatic system to aid in virulence 29, 30.

Recent empirical evidence has shown that, in fact, multiple in vitro substrates of Pla have limited or no impact on the development of disease in vivo, including the group II substrate peroxiredoxin‐6 and the group III substrate A2AP 32, 33. Indeed, to date only one in vitro‐described Pla group I substrate, the apoptotic molecule Fas ligand (FasL), has been reported to contribute to disease during pneumonic plague 34. It has been hypothesized that the inactivation of PAI‐1 by Pla could serve as a mechanism by which Y. pestis alleviates endogenous PA inhibition in vivo to promote disease by enhancing plasmin generation, thus facilitating bacterial outgrowth and dissemination 30, 31, 35, 36, 37, 38.

In this article, we report that the Pla protease cleaves and inactivates PAI‐1 serpin activity during pneumonic plague. The loss of PAI‐1 results in increased pulmonary plasmin levels and promotes the outgrowth of Y. pestis bacilli in the lungs. In addition, the absence of PAI‐1 causes changes in the host response to Y. pestis infection, resulting in altered neutrophil recruitment, cytokine production, and tissue barrier permeability. Thus, our data show that PAI‐1 is a group I substrate of Pla, and that the inactivation of PAI‐1 by Y. pestis alters the host environment to facilitate the development of pneumonic plague.

Materials and methods

Reagents, bacterial strains, and culture conditions

Reagents for this study were purchased from either Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) or VWR (Batavia, IL, USA), unless otherwise stated. Y. pestis strains were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth or on BHI agar (VWR). For animal infections, Y. pestis strains were cultured in BHI at 37 °C with the addition of 2.5 mm CaCl2, as previously described 26. All experiments with select agent strains of Y. pestis CO92 were conducted in a Centers for Disease Control‐approved BSL‐3/ABSL‐3 facility at Northwestern University.

Animal infections

All procedures involving animals were carried out in compliance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Northwestern University. C57BL/6 mice, aged 6–8 weeks, were bred at Northwestern University or purchased from The Jackson Laboratories (Farmington, CT, USA). Breeding pairs of C57BL/6 PAI‐1 −/− mice were obtained from Dr Douglas Vaughan (Northwestern University). For infections, mice were age‐matched and sex‐matched, anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine, and infected by the intranasal route (104, 106 or 108 colony‐forming units [CFUs]) with Y. pestis diluted in phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), as previously described 26, 34. Mice were killed by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium, followed by organ removal or cervical dislocation. All animal infections were performed at least twice, and the data were combined.

To determine the bacterial burden, mice were inoculated intranasally with Y. pestis, and mice were killed at various times after infection. Subsequently, the lungs and spleens were removed, weighed, homogenized in sterile PBS, serially diluted, and plated onto BHI agar. To determine the survival of mice following infection, mice were inoculated intranasally with Y. pestis and monitored every 12 h for up to 10 days.

Histopathology

Mice were inoculated intranasally with Y. pestis, and at 48 h mice were killed and the lungs were inflated with 1 mL of 10% neutral buffered formalin via tracheal cannulation, removed, fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, as previously described 32, 33. Inflamed lesions were analyzed with imagej to calculate the area of inflammation. Data represent the lesion area (mm2) per field in two sections from three mice each at × 2.5 magnification.

Innate immune cell quantification

Mice were infected intranasally with Y. pestis or mock‐infected with PBS, and at 48 h mice were killed and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed, as described previously 34. BAL fluid (BALF) was collected by pooling five 1‐mL lavages with PBS per mouse; the first 1 mL of the BALF was reserved for analyses of cytokines or specific hemostatic proteins (see below). Samples were processed, stained, and analyzed by flow cytometry, as previously described 32, 33.

Cytokine analysis

At 48 h after inoculation with PBS or Y. pestis, the levels of interleukin (IL)‐12p70, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α, interferon (IFN)‐γ, monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1 (MCP‐1) and IL‐6 were quantitatively established from the supernatant of the collected BALF by use of the cytometric bead array technique (BD Cytometric Bead Array Mouse Inflammation Kit; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) as specified by the manufacturer. Data were analyzed with bd cytometric bead array software.

Quantification of total, active and cleaved PAI‐1 in BALF

PAI‐1 levels in BALF were assessed with a total PAI‐1 ELISA (Molecular Innovations, Novi, MI, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Additionally, the levels of active PAI‐1 in the BALF were assessed with an active PAI‐1 ELISA (Molecular Innovations). For both ELISAs, the absorbance at 450 nm was measured in a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Data from three independent experiments assessed in duplicate were combined. To assess PAI‐1 cleavage in vitro, 0.15 μg of purified recombinant mouse PAI‐1 (Abcam, Cambridge, VT, USA) was incubated with 1 × 107 CFUs of Y. pestis or Y. pestis ∆pla in PBS, and supernatants were collected after 10 min. For immunoblot analyses, purified mouse PAI‐1 (Abcam) or BALF was separated by reducing SDS‐PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with an anti‐mouse PAI‐1 antibody (Abcam). For in vivo analysis, each blot is representative of three independent experiments, and each lane represents BALF from a single mouse.

Quantification of plasminogen cleavage and plasmin activity

Plasmin activity in BALF was assessed as described previously with the chromogenic substrate D‐AFK‐ANSNH‐iC4H9‐2HBr (SN5; Hematologic Technologies, Essex Junction, VT, USA) 22, 26. Data are represented as the relative fluorescence at 120 min combined from two independent experiments performed in triplicate. Purified murine plasminogen (Haematologic Technologies), purified murine plasmin (Haematologic Technologies) or BALF from each of the indicated infections was separated by reducing SDS‐PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with an anti‐mouse plasmin(ogen) antibody (Haematologic Technologies), as described previously 32.

Statistics

Statistical means are plotted, and error bars represent standard errors of the mean. The Mann–Whitney U‐test was used for bacterial load comparisons, the Kaplan–Meier test was used for comparison of survival curves, and all other experiments were analyzed by one‐way anova with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test where indicated, with graphpad prism 5.

Results

PAI‐1 is cleaved and inactivated in the lungs by the Pla protease

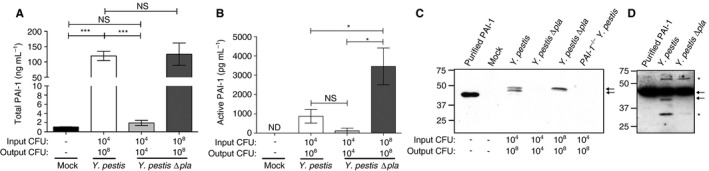

To determine whether the Pla protease of Y. pestis inactivates PAI‐1 in vivo, we inoculated wild‐type C57BL/6 mice via the intranasal route with PBS (mock) or with equivalent doses (104 CFUs) of Y. pestis strain CO92 or an isogenic mutant of Y. pestis CO92 lacking Pla 26. We found that the levels of total PAI‐1 were significantly increased in the lungs in response to Y. pestis infection as compared with uninfected mice (Fig. 1A). The levels of PAI‐1 in the lungs of wild‐type Y. pestis‐infected mice were also increased as compared with those in Y. pestis ∆pla‐infected mice, most likely because of the difference in bacterial load between the strains at 48 h after infection (‘output CFU’) (Fig. 1A). Therefore, to assess the impact of Pla on PAI‐1 levels when bacterial loads were equivalent, we increased the inoculum (‘input CFU’) of Y. pestis ∆pla to 108, so that the output CFU at 48 h was matched to the output CFU of the wild‐type strain 32, 33, 34. We found no difference in the levels of total PAI‐1 in the lungs at 48 h when output CFUs were equivalent (Fig. 1A). We also assessed the levels of active PAI‐1 present in the same BALF by using an active PAI‐1‐specific ELISA. In contrast to total PAI‐1, there was a significant decrease in the level of active PAI‐1 in wild‐type Y. pestis‐infected mice as compared with ∆pla‐infected mice, when output CFUs were matched (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 (PAI‐1) is cleaved and inactivated by the Pla protease in vivo. (A, B) Quantification of (A) total PAI‐1 and (B) active PAI‐1 by ELISA recovered by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of C57BL/6 mouse lungs 48 h after inoculation with phosphate‐buffered saline (mock), 104 colony‐forming units (CFUs) of Yersinia pestis, 104 CFUs of Y. pestis ∆pla, or 108 CFUs of Y. pestis ∆pla. Data from two independent experiments are combined (n = 10 for each group); error bars represent standard errors of the mean (SEMs), and significance was determined by one‐way anova with Bonferroni's multiple comparison (*P ≤ 0.05; ***P ≤ 0.001). (C, D) Immunoblot analysis of PAI‐1 recovered by BAL (C) or PAI‐1 cleaved in vitro (D). Blots are representative of three independent experiments. Arrows represent full‐length PAI‐1 protein and cleavage product; asterisks indicate non‐specific bands. Numbers to the left of the blot indicate molecular masses in kilodaltons. Note that purified, recombinant PAI‐1 migrates at a lower molecular mass than PAI‐1 isolated from mouse BAL fluid, owing to the lack of post‐translational modifications on the protein. The input CFU and output CFU are included below each figure to denote the number of bacteria inoculated and the number at the time of assessment, respectively. ND, not detectable; NS, not significant.

To determine whether the cleavage of PAI‐1 by Pla could be observed in vivo, we analyzed the same BALF by immunoblotting with an antibody against total PAI‐1. Although PAI‐1 protein was not detectable in the lung airspaces of uninfected mice or mice infected with 104 CFUs of Y. pestis ∆pla, we observed a single species at ~ 47 kDa, corresponding to full‐length, glycosylated PAI‐1 7, in the lungs of mice infected with 108 CFUs of Y. pestis ∆pla (Fig. 1C), consistent with the ELISA data in Fig. 1A. Infection with wild‐type Y. pestis also resulted in detectable full‐length PAI‐1; however, we also observed a second, slightly faster migrating band that was not present in any other condition (Fig. 1C). Incubation of recombinant mouse PAI‐1 with Y. pestis in vitro showed a similar Pla‐dependent cleavage product of PAI‐1 (Fig. 1D, lower arrow), consistent with the characterized cleavage of human PAI‐1 by Pla in vitro 29. This suggests that Pla directly cleaves PAI‐1 in the lungs. From these data, we conclude that the presence of Y. pestis bacteria in the lungs increases the levels of PAI‐1 in the airspace, but that PAI‐1 is cleaved and inactivated in a Pla‐dependent manner during pneumonic plague.

PAI‐1 restricts the proliferation of Y. pestis in the absence of Pla

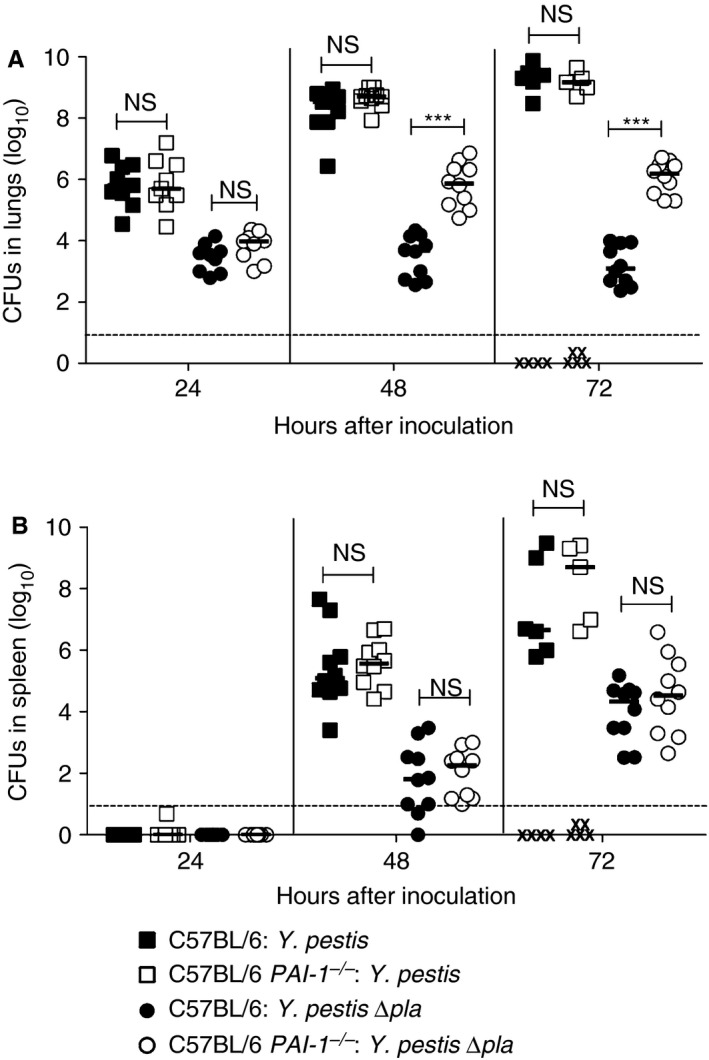

As Pla contributes to the proliferation of Y. pestis in the lungs 26, and Pla inactivates PAI‐1 during pneumonic plague, we hypothesized that the loss of PAI‐1 would partially compensate for the absence of Pla. To test this, wild‐type or PAI‐1 −/− mice were infected intranasally, and CFUs in the lungs and spleens were enumerated. We found no difference in the number of CFUs in the lungs at any point between wild‐type and PAI‐1 −/− mice after infection with wild‐type Y. pestis (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, we observed a 100–1000‐fold increase in the number of CFUs of the ∆pla strain in the lungs of PAI‐1 −/− mice as compared with wild‐type mice at both 48 h and 72 h after infection (Fig. 2A). However, this enhanced outgrowth in the lungs did not enhance bacterial dissemination, as determined by measuring the number of CFUs in the spleen (Fig. 2B). Finally, we tested the impact of PAI‐1 deficiency on the survival of mice following intranasal infection, and observed no difference in the survival of PAI‐1 −/− mice as compared with wild‐type controls after infection with either wild‐type Y. pestis or the ∆pla mutant (Fig. 3). These data indicate that PAI‐1 cleavage contributes to bacterial outgrowth in the lungs but not during systemic infection.

Figure 2.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 (PAI‐1) restricts the outgrowth of Yersinia pestis in the absence of Pla. (A, B) Bacterial burden in the (A) lungs and (B) spleens of C57BL/6 or C57BL/6 PAI‐1 −/− mice infected with 104 colony‐forming units (CFUs) of Y. pestis or Y. pestis ∆pla at the indicated times. Each point represents the numbers of bacteria recovered from a single mouse. An ‘X’ indicates a mouse that succumbed to the infection, the median number of CFUs is denoted by a solid line, and the dashed line indicates the limit of detection. Data from two independent experiments are combined (n = 10 for each group). The Mann–Whitney U‐test was used for comparison of bacterial burden measurements (***P ≤ 0.001). NS, not significant.

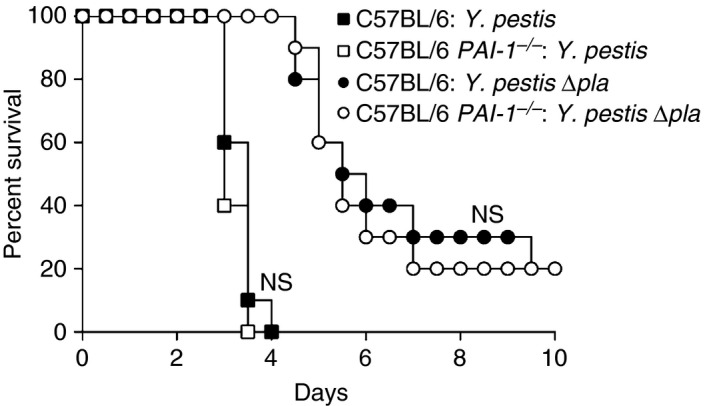

Figure 3.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 (PAI‐1) is dispensable for survival during Yersinia pestis respiratory infection. Survival over time of C57BL/6 or C57BL/6 PAI‐1 −/− mice infected with 104 colony‐forming units of Y. pestis or Y. pestis ∆pla. Data from two independent experiments are combined (n = 20 for each group). The Kaplan–Meier test was used to determine the significance of differences in survival rates between wild‐type and PAI‐1 −/− mice. NS, not significant.

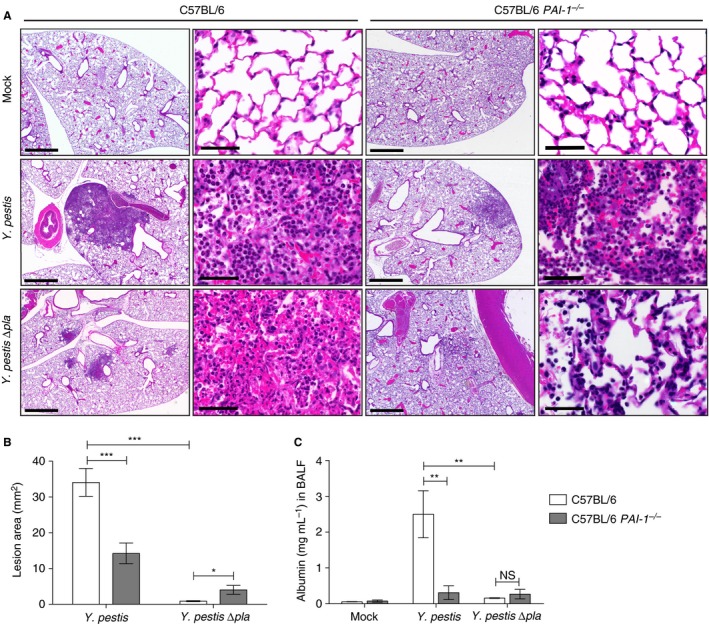

PAI‐1 enhances lung pathology during Y. pestis infection

To determine the impact of PAI‐1 on the host response to pneumonic plague, we evaluated the overall histopathology of infected lungs in the presence or absence of PAI‐1. This analysis revealed a noticeable reduction in the gross size of the inflammatory lesions in PAI‐1 −/− mice as compared with wild‐type mice after infection with wild‐type Y. pestis (Fig. 4A; Fig. S1). This was confirmed by the quantification of lesion size by imagej analysis (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, we observed more intact lung architecture throughout the lesions of PAI‐1 −/− mice than in the lesions of wild‐type mice (Fig. 4A). Consistent with these observations, the levels of serum albumin present in the lung airspaces of PAI‐1 −/− mice were significantly reduced as compared with wild‐type mice (Fig. 4C), suggesting that the presence of PAI‐1 affects tissue barrier integrity during infection. However, wild‐type and PAI‐1 −/− mice infected with Y. pestis ∆pla had equivalent levels of albumin in the lung airspace (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 (PAI‐1) enhances lung pathology during Yersinia pestis infection. (A) Sections of formalin‐fixed lungs stained with hematoxylin and eosin from C57BL/6 or C57BL/6 PAI‐1 −/− mice inoculated with phosphate‐buffered saline (mock), 104 colony‐forming units (CFUs) of Y. pestis, or 104 CFUs of Y. pestis ∆pla. Representative images of inflammatory lesions are shown (n = 3). For each infection, the scale bar of the left image (× 2.5 magnification) represents 100 μm, and the scale bar of the right image (× 63 magnification) represents 50 μm. (B) Inflamed lesions were analyzed with imagej to calculate the area of inflammation. Data represent the lesion area (mm2) per field in two sections from three mice, each at × 2.5 magnification. (C) Quantification by ELISA of albumin levels in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of C57BL/6 or C57BL/6 PAI‐1 −/− mice infected with 104 CFU of Y. pestis or Y. pestis ∆pla, or mock‐infected. Data from two independent experiments are combined (n = 10 for each group), and error bars represent standard errors of the mean (SEMs). One‐way anova with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test was used to determine significance (*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001). NS, not significant.

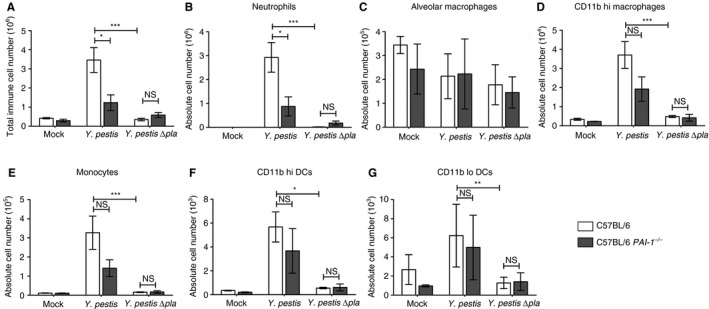

PAI‐1 promotes neutrophil recruitment to the lungs during pneumonic plague

PAI‐1 has been shown to contribute to immune cell recruitment in the lungs during bacterial pneumonia 11, 14. We found that the lungs of wild‐type mice infected with Y. pestis contained significantly more immune cells than those of PAI‐1 −/− (Fig. 5A). Wild‐type mice infected with Y. pestis ∆pla showed a significant reduction in the total number of immune cells recruited to the lungs as compared with those infected with wild‐type Y. pestis. However, PAI‐1 deficiency did not alter the total number of immune cells present in the airspaces of mice infected with Y. pestis ∆pla as compared with the wild‐type (Fig. 5A). We found that, of these immune cells, neutrophils were the only population to show a significant reduction in recruitment to the lungs of Y. pestis‐infected PAI‐1 −/− mice as compared with wild‐type mice (Fig. 5B–G).

Figure 5.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 (PAI‐1) promotes neutrophil recruitment during Yersinia pestis infection. C57BL/6 or C57BL/6 PAI‐1 −/− mice were inoculated with phosphate‐buffered saline (mock), 104 colony‐forming units (CFUs) of Y. pestis, or 104 CFUs of Y. pestis ∆pla, and after 48 h bronchoalveolar lavage was performed to recover immune cells. (A) The total numbers of cells recruited to the lungs were determined by counting on a hemacytometer. (B–G) Flow cytometry was performed to determine the absolute numbers of (B) neutrophils, (C) alveolar macrophages, (D) CD11b hi macrophages, (E) monocytes, (F) CD11b hi dendritic cells (DCs) and (G) CD11b lo DCs recruited to the lungs. Data from two or three independent experiments are combined (n = 10–15 for each group); error bars represent standard errors of the mean. One‐way anova with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test was used to determine significance (*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001). NS, not significant.

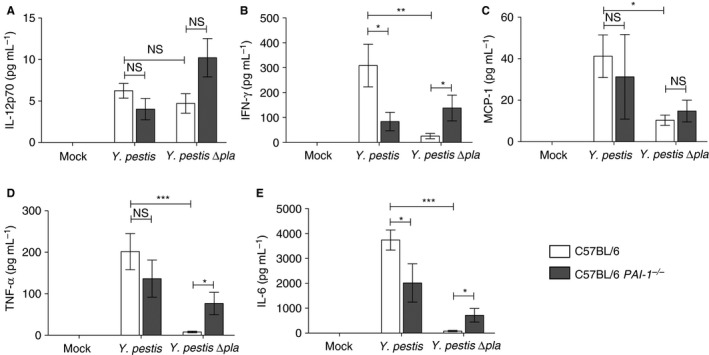

PAI‐1 contributes to the regulation of cytokine production during Y. pestis respiratory infection

The hemostatic system is tightly linked to the inflammatory response and the production of cytokines 6, 39. Therefore, we investigated the effects of PAI‐1 deficiency on cytokine levels, and found that the levels of IL‐12p70, TNF‐α and MCP‐1 were unchanged in PAI‐1 −/− mice infected with Y. pestis as compared with wild‐type mice (Fig. 6A,C,D). However, we did observe a significant decrease in the levels of both IFN‐γ and IL‐6 (Fig. 6B,E). In contrast, in PAI‐1 −/− mice infected with Y. pestis ∆pla, we detected significant increases in the levels of IFN‐γ, TNF‐α and IL‐6 in the lung airspaces as compared with wild‐type mice (Fig. 6B,D,E). These results indicate that PAI‐1 enhances the inflammatory response during wild‐type Y. pestis infection, whereas it acts a suppressor of inflammatory cytokine production during Y. pestis ∆pla infection.

Figure 6.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 (PAI‐1) regulates cytokine production during pneumonic plague. Forty‐eight hours after inoculation with phosphate‐buffered saline (mock), 104 colony‐forming units (CFUs) of Yersinia pestis, or 104 CFUs of Y. pestis ∆pla, the levels of the indicated cytokines present in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of C57BL/6 or C57BL/6 PAI‐1 −/− mice were assessed by cytometric bead array. Data from two or three independent experiments are combined (n = 10–15 for each group); error bars represent standard errors of the mean. One‐way anova with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test was used to determine significance (*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001). IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; MCP‐1, monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1; NS, not significant; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

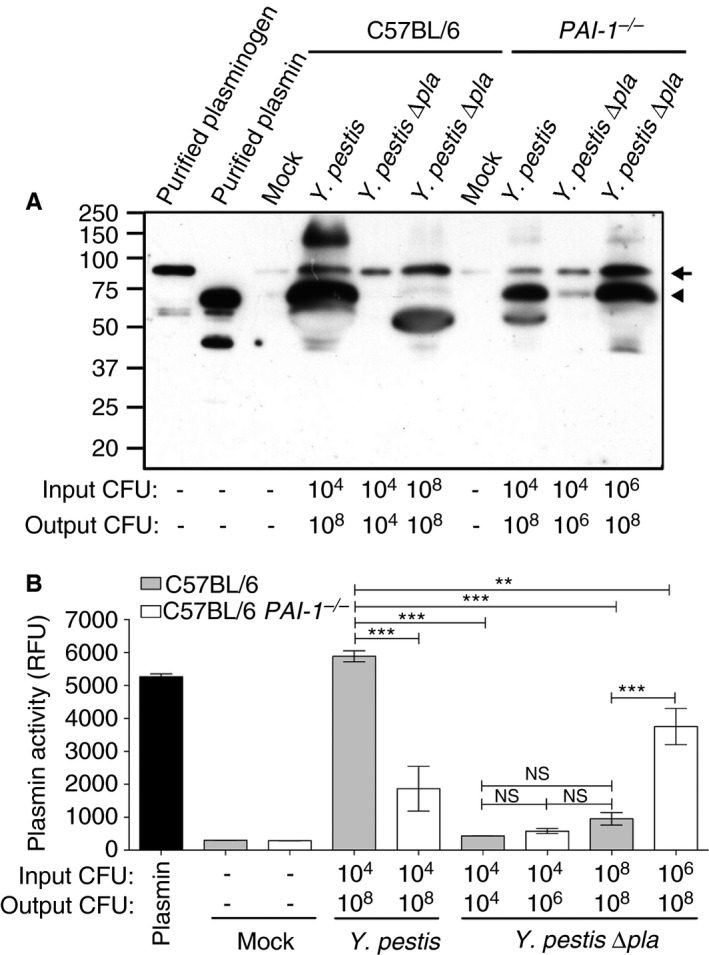

PAI‐1 restricts plasminogen activation in the lungs of Y. pestis ∆pla‐infected mice

We have previously shown that Y. pestis generates high levels of plasmin in the lungs in a Pla‐dependent manner 32. Therefore, we hypothesized that the inactivation of PAI‐1 by Pla would result in increased plasmin levels during infection. The level of plasmin is robustly increased in the lungs of mice infected with wild‐type Y. pestis as compared with both mock‐infected and Y. pestis ∆pla‐infected mice; dose‐matched ∆pla infection results in a higher level of total plasminogen but little or no plasmin (Fig. 7A). In PAI‐1 −/− mice infected with wild‐type Y. pestis, we found that the presence of Pla also increased the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, but not to the same extent as in wild‐type mice, most likely because of reduced immune cell recruitment and tissue damage (Figs. 4C and 5B). In PAI‐1 −/− mice, we observed an increase in the level of plasmin in the airspace as compared with wild‐type mice after infection with Y. pestis ∆pla (Fig. 7A). When the inoculum of the Y. pestis ∆pla strain is increased so that the output CFU is equivalent to that of a Y. pestis infection, we found that the lack of PAI‐1 enhances the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin (Fig. 7A). To confirm these observations, we assessed the levels of active plasmin via cleavage of a plasmin‐specific chromogenic substrate, and found that the data mimicked those obtained with immunoblotting (Fig. 7B). Although the differences in the levels of active plasmin in the airspaces did not reach statistical significance on comparison of Y. pestis ∆pla infection of wild‐type mice and PAI‐1 −/− mice infected with 104 CFUs, the effects of PAI‐1 and Pla on active plasmin generation were clear on comparison of Y. pestis ∆pla dose‐matched samples in wild‐type and PAI‐1 −/− mice (Fig. 7B). These data confirm that, when bacterial loads are equivalent and hemostatic proteins have access to the lung airspace, PAI‐1 restricts endogenous plasminogen activation, and that Pla can subsequently overcome this effect.

Figure 7.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 (PAI‐1) restricts endogenous plasmin(ogen) activation in the lungs of Yersinia pestis ∆pla‐infected mice. (A) Immunoblot analysis of plasmin(ogen) recovered by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) from C57BL/6 or C57BL/6 PAI‐1 −/− mice inoculated with phosphate‐buffered saline (mock) or the indicated strains. The arrow indicates plasmin(ogen), and the arrowhead indicates plasmin. Numbers to the left of the blot indicate molecular masses in kilodaltons. The blot is representative of three independent experiments. (B) Quantification of active plasmin levels present in the BAL fluid as described above or purified active murine plasmin. Data are presented as relative fluorescence units (RFUs) at 120 min, and are combined from two independent experiments plated in triplicate; error bars represent standard errors of the mean. One‐way anova with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test was used to determine significance (*P ≤ 0.05, ***P ≤ 0.01). CFU, colony‐forming unit; NS, not significant.

Discussion

In vitro, the Pla protease of Y. pestis has been shown to inactivate multiple regulators of host hemostasis while simultaneously converting plasminogen to plasmin 24, 29, 30. Thus, it has been widely hypothesized that Pla contributes to virulence not only by generating plasmin but also by circumventing the activity of endogenous inhibitors of fibrinolysis 30, 31, 35, 36, 37, 38. We recently found that, in fact, Pla does not cleave A2AP in vivo, and nor does A2AP have an effect on either bacterial outgrowth or disease progression in a mouse model of pneumonic plague 32. This study suggests that plasmin is excessively generated during a Y. pestis infection to an extent that A2AP cannot overcome 32.

Here, we investigated the contribution of the Pla substrate PAI‐1 to the development of primary pneumonic plague. Our data clearly demonstrate that murine PAI‐1 is cleaved and inactivated by Y. pestis in a Pla‐dependent manner during pneumonic plague. The cleavage of human PAI‐1 by Pla occurs between residues Arg346 and Met347 within the reactive center loop of PAI‐1, removing ~ 20 residues from the C‐terminus of the protein 29. Although this proteolysis event inhibits the serpin activity of PAI‐1, a biologically active but serpin‐defective form of PAI‐1 may remain. Some of the serpin‐independent functions attributed to PAI‐1 include the regulation of immune cell migration, binding to cell surface receptors, and the activation of intracellular signaling cascades 5, 6, 7. Thus, Pla‐cleaved PAI‐1 may still contribute to the host response to plague. Alternatively, there may be sufficient uncleaved PAI‐1 present in the lungs that retains full activity, thereby limiting the impact of Pla via PAI‐1 inhibition (providing an explanation for the differences between wild‐type and PAI‐1 −/− mice following Y. pestis infection). In addition, although Pla can cleave both human and mouse PAI‐1, differences between the species may result in different consequences for the host during infection.

We report that PAI‐1 restricts the outgrowth of Y. pestis ∆pla in the lungs. These results demonstrate that PAI‐1 serves as a protective host defense mechanism for Y. pestis during pneumonic plague in the absence of Pla. Interestingly, bacterial proliferation in the lungs in the absence of PAI‐1 does not correspond with enhanced dissemination or the outcome of disease (i.e. survival), suggesting additional activities of Pla that are independent of PAI‐1 cleavage.

PAI‐1 has been shown to affect both immune cell recruitment and cytokine production via its regulation of the hemostatic system and through mechanisms that are independent of its serpin activity 5, 6. Here, we demonstrate that PAI‐1 deficiency impacts the immune response to both Y. pestis and Y. pestis ∆pla infection. During a wild‐type Y. pestis infection, the absence of PAI‐1 significantly decreases neutrophil recruitment to the lungs. This is consistent with a wide array of literature demonstrating the critical role of PAI‐1 in the recruitment of neutrophils to the pulmonary compartment following infection with other respiratory pathogens 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. However, during these infections, the absence of PAI‐1 increases bacterial outgrowth, which is in contrast to our findings with wild‐type Y. pestis, but consistent with ∆pla infection. This suggests that Y. pestis, which encodes a direct PA, must still overcome the inhibitory effects of PAI‐1, and requires additional endogenous plasminogen activation, at least in the lungs. Furthermore, the control and clearance of multiple bacterial pathogens is highly dependent on the presence of neutrophils 40, 41, 42, whereas Y. pestis outgrowth is unchanged following depletion of neutrophils 43. This provides another potential explanation for the differences in the phenotypes observed in PAI‐1 −/− mice with different pathogens. The significant reduction in the number of neutrophils recruited to the lungs in the absence of PAI‐1 probably explains the lack of damage to tissue barrier integrity, as pneumonic plague is primarily a host‐driven disease mediated through neutrophils 43.

PAI‐1 also impacts cytokine production in response to Y. pestis, probably as a consequence of its role in regulating neutrophil recruitment. Wild‐type mice infected with Y. pestis show increased levels of the cytokines IFN‐γ and IL‐6 in the lung compartment as compared with PAI‐1 −/− mice. Thus, in a wild‐type Y. pestis infection, the reduction in polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration in PAI‐1 −/− mice may contribute to the diminished levels of these cytokines. In contrast, there are minimal levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the airspaces of wild‐type mice infected with the ∆pla strain, as Pla is absolutely required for the transition to the proinflammatory phase of pneumonic plague 26, 44. However, PAI‐1 deficiency can restore part of this transition, as the levels of IFN‐γ, TNF‐α and IL‐6 are all significantly increased, a phenomenon that is also seen in A2AP‐deficient mice infected with Y. pestis ∆pla 32.

These seemingly paradoxical results suggest that Pla probably contributes to other aspects of the innate immune response beyond PAI‐1 cleavage (such as is observed with the Pla‐mediated inactivation of FasL) 34. In addition, it has been repeatedly demonstrated that PAI‐1 can have both positive and negative effects on inflammation, depending on experimental conditions, cell types studied, and other factors 45. A study on bubonic plague demonstrated that PAI‐1 and fibrin deficiency have similar phenotypes regarding innate immune cell responses, thus highlighting the importance of fibrinolysis during Y. pestis infection and inflammation 46. However, that study used a strain of Y. pestis engineered to produce a more stimulatory form of lipopolysaccharide, and administration was performed through a different route, thus potentially explaining the differences between our studies.

These data, combined with our previous work, allow us to formulate a hypothesis on the mechanisms by which the Pla protease disrupts the regulation of fibrinolysis during pneumonic plague. In a wild‐type Y. pestis infection, the Pla protease potently converts plasminogen into active plasmin, while at the same time disrupting the serpin activity of PAI‐1, thus enhancing endogenous plasminogen activation. When these activities are combined, the excess plasmin generated during infection cannot be overcome by the inhibitory effects of A2AP 32. In contrast, during a Y. pestis ∆pla infection, the absence of either A2AP or PAI‐1 increases the levels of free plasmin present in the lung airspace; however, this is not sufficient for the full virulence of Y. pestis in the lungs (because of either limited plasmin abundance or other activities associated with Pla). The loss of PAI‐1 results in 2–3 logs greater bacterial outgrowth in the absence of Pla, but, ultimately, neither A2AP nor PAI‐1 deficiency alters the outcome of infection. This is supported by data demonstrating that, once the bacteria have invaded the bloodstream, the Pla protease is no longer required for infection, as mice succumb to sepsis. Further studies on the role of plasmin during pneumonic plague will elucidate the contributions of plasminogen activation versus other activities of PAI‐1 during Y. pestis infection, and the impact of Pla on these processes.

Addendum

W. W. Lathem and J. L. Eddy were responsible for concept and design. J. L. Eddy, J. A. Schroeder, D. L. Zimbler, and A. J. Caulfield performed the experiments. J. L. Eddy and W. W. Lathem interpreted the date and drafted the manuscript.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interests

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Additional histologic sections of formalin‐fixed lungs stained with H&E from C57BL/6 or C57BL/6 PAI‐1 −/− mice inoculated with 104 CFUs of Y. pestis or Y. pestis Δpla.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Douglas Vaughan, Northwestern University, for the kind gift of PAI‐1 −/− mice, and members of the Lathem Laboratory for technical support. Flow cytometry was performed at the Northwestern University Interdepartmental Immunobiology Flow Cytometry Core Facility, histopathologic studies were performed by the Northwestern University Mouse Histology and Phenotyping Laboratory, and imaging was performed at the Northwestern University Cell Imaging Facility. This work was supported by funding from Public Health Grants NIAID R01 AI093727 and R21 AI103658 to W. W. Lathem, NCI CA060554 to the Northwestern University Mouse Histology and Phenotyping Laboratory, and NCI CCSG P30 CA060553 to the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Eddy JL, Schroeder JA, Zimbler DL, Caulfield AJ, Lathem WW. Proteolysis of plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 by Yersinia pestis remodulates the host environment to promote virulence. J Thromb Haemost 2016; 14: 1833–43.

Manuscript handled by T. Lisman

Final decision: P. H. Reitsma, 27 May 2016

References

- 1. van Gorp EC, Suharti C, ten Cate H, Dolmans WM, van der Meer JW, ten Cate JW, Brandjes DP. Review: infectious diseases and coagulation disorders. J Infect Dis 1999; 180: 176–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ploplis VA, Castellino FJ. Gene targeting of components of the fibrinolytic system. Thromb Haemost 2002; 87: 22–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Collen D. Identification and some properties of a new fast‐reacting plasmin inhibitor in human plasma. Eur J Biochem 1976; 69: 209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hekman CM, Loskutoff DJ. Kinetic analysis of the interactions between plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 and both urokinase and tissue plasminogen activator. Arch Biochem Biophys 1988; 262: 199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ghosh AK, Vaughan DE. PAI‐1 in tissue fibrosis. J Cell Physiol 2012; 227: 493–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lijnen HR. Pleiotropic functions of plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1. J Thromb Haemost 2005; 3: 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yasar Yildiz S, Kuru P, Toksoy Oner E, Agirbasli M. Functional stability of plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014; 2014: 858293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Declerck PJ, De Mol M, Alessi MC, Baudner S, Paques EP, Preissner KT, Muller‐Berghaus G, Collen D. Purification and characterization of a plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 binding protein from human plasma. Identification as a multimeric form of S protein (vitronectin). J Biol Chem 1988; 263: 15454–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Andreasen PA, Egelund R, Petersen HH. The plasminogen activation system in tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. Cell Mol Life Sci 2000; 57: 25–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Taeye B, Smith LH, Vaughan DE. Plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1: a common denominator in obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2005; 5: 149–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goolaerts A, Lafargue M, Song Y, Miyazawa B, Arjomandi M, Carles M, Roux J, Howard M, Parks DA, Iles KE, Pittet JF. PAI‐1 is an essential component of the pulmonary host response during Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in mice. Thorax 2011; 66: 788–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Renckens R, Roelofs JJ, Bonta PI, Florquin S, de Vries CJ, Levi M, Carmeliet P, van't Veer C, van der Poll T. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 is protective during severe Gram‐negative pneumonia. Blood 2007; 109: 1593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rijneveld AW, Florquin S, Bresser P, Levi M, De Waard V, Lijnen R, Van Der Zee JS, Speelman P, Carmeliet P, Van Der Poll T. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type‐1 deficiency does not influence the outcome of murine pneumococcal pneumonia. Blood 2003; 102: 934–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kager LM, Wiersinga WJ, Roelofs JJ, Meijers JC, Levi M, Van't Veer C, van der Poll T.. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type I contributes to protective immunity during experimental Gram‐negative sepsis (melioidosis). J Thromb Haemost 2011; 9: 2020–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lim JH, Woo CH, Li JD. Critical role of type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI‐1) in early host defense against nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) infection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011; 414: 67–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kunert A, Losse J, Gruszin C, Huhn M, Kaendler K, Mikkat S, Volke D, Hoffmann R, Jokiranta TS, Seeberger H, Moellmann U, Hellwage J, Zipfel PF. Immune evasion of the human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa: elongation factor Tuf is a factor H and plasminogen binding protein. J Immunol 2007; 179: 2979–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sjobring U, Pohl G, Olsen A. Plasminogen, absorbed by Escherichia coli expressing curli or by Salmonella enteritidis expressing thin aggregative fimbriae, can be activated by simultaneously captured tissue‐type plasminogen activator (t‐PA). Mol Microbiol 1994; 14: 443–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Coleman JL, Gebbia JA, Piesman J, Degen JL, Bugge TH, Benach JL. Plasminogen is required for efficient dissemination of B. burgdorferi in ticks and for enhancement of spirochetemia in mice. Cell 1997; 89: 1111–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Collen D. Staphylokinase: a potent, uniquely fibrin‐selective thrombolytic agent. Nat Med 1998; 4: 279–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sun H, Ringdahl U, Homeister JW, Fay WP, Engleberg NC, Yang AY, Rozek LS, Wang X, Sjobring U, Ginsburg D. Plasminogen is a critical host pathogenicity factor for group A streptococcal infection. Science 2004; 305: 1283–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang XZ, Nikolich MP, Lindler LE. Current trends in plague research: from genomics to virulence. Clin Med Res 2006; 4: 189–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eddy JL, Gielda LM, Caulfield AJ, Rangel SM, Lathem WW. Production of outer membrane vesicles by the plague pathogen Yersinia pestis . PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e107002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beesley ED, Brubaker RR, Janssen WA, Surgalla MJ. Pesticins. 3. Expression of coagulase and mechanism of fibrinolysis. J Bacteriol 1967; 94: 19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sodeinde OA, Subrahmanyam YV, Stark K, Quan T, Bao Y, Goguen JD. A surface protease and the invasive character of plague. Science 1992; 258: 1004–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sebbane F, Jarrett CO, Gardner D, Long D, Hinnebusch BJ. Role of the Yersinia pestis plasminogen activator in the incidence of distinct septicemic and bubonic forms of flea‐borne plague. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103: 5526–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lathem WW, Price PA, Miller VL, Goldman WE. A plasminogen‐activating protease specifically controls the development of primary pneumonic plague. Science 2007; 315: 509–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lathem WW, Crosby SD, Miller VL, Goldman WE. Progression of primary pneumonic plague: a mouse model of infection, pathology, and bacterial transcriptional activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102: 17786–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Robbins KC, Summaria L, Hsieh B, Shah RJ. The peptide chains of human plasmin. Mechanism of activation of human plasminogen to plasmin. J Biol Chem 1967; 242: 2333–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haiko J, Laakkonen L, Juuti K, Kalkkinen N, Korhonen TK. The omptins of Yersinia pestis and Salmonella enterica cleave the reactive center loop of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1. J Bacteriol 2010; 192: 4553–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kukkonen M, Lahteenmaki K, Suomalainen M, Kalkkinen N, Emody L, Lang H, Korhonen TK. Protein regions important for plasminogen activation and inactivation of alpha2‐antiplasmin in the surface protease Pla of Yersinia pestis . Mol Microbiol 2001; 40: 1097–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Suomalainen M, Haiko J, Ramu P, Lobo L, Kukkonen M, Westerlund‐Wikstrom B, Virkola R, Lahteenmaki K, Korhonen TK. Using every trick in the book: the Pla surface protease of Yersinia pestis . Adv Exp Med Biol 2007; 603: 268–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eddy JL, Schroeder JA, Zimbler DL, Bellows LE, Lathem WW. Impact of the Pla protease substrate alpha2‐antiplasmin on the progression of primary pneumonic plague. Infect Immun 2015; 83: 4837–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zimbler DL, Eddy JL, Schroeder JA, Lathem WW. Inactivation of peroxiredoxin 6 by the Pla protease of Yersinia pestis . Infect Immun 2016; 84: 365–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Caulfield AJ, Walker ME, Gielda LM, Lathem WW. The Pla protease of Yersinia pestis degrades fas ligand to manipulate host cell death and inflammation. Cell Host Microbe 2014; 15: 424–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Caulfield AJ, Lathem WW. Substrates of the plasminogen activator protease of Yersinia pestis . Adv Exp Med Biol 2012; 954: 253–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Degen JL, Bugge TH, Goguen JD. Fibrin and fibrinolysis in infection and host defense. J Thromb Haemost 2007; 5(Suppl. 1): 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Haiko J, Kukkonen M, Ravantti JJ, Westerlund‐Wikstrom B, Korhonen TK. The single substitution I259T, conserved in the plasminogen activator Pla of pandemic Yersinia pestis branches, enhances fibrinolytic activity. J Bacteriol 2009; 191: 4758–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Korhonen TK, Haiko J, Laakkonen L, Jarvinen HM, Westerlund‐Wikstrom B. Fibrinolytic and coagulative activities of Yersinia pestis . Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2013; 3: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O'Brien M. The reciprocal relationship between inflammation and coagulation. Top Companion Anim Med 2012; 27: 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Easton A, Haque A, Chu K, Lukaszewski R, Bancroft GJ. A critical role for neutrophils in resistance to experimental infection with Burkholderia pseudomallei . J Infect Dis 2007; 195: 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Koh AY, Priebe GP, Ray C, Van Rooijen N, Pier GB. Inescapable need for neutrophils as mediators of cellular innate immunity to acute Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Infect Immun 2009; 77: 5300–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xiong H, Carter RA, Leiner IM, Tang YW, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, Pamer EG. Distinct contributions of neutrophils and CCR2+ monocytes to pulmonary clearance of different Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. Infect Immun 2015; 83: 3418–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pechous RD, Sivaraman V, Price PA, Stasulli NM, Goldman WE. Early host cell targets of Yersinia pestis during primary pneumonic plague. PLoS Pathog 2013; 9: e1003679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zimbler DL, Schroeder JA, Eddy JL, Lathem WW. Early emergence of Yersinia pestis as a severe respiratory pathogen. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vaughan DE. PAI‐1 and cellular migration: dabbling in paradox. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002; 22: 1522–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Luo D, Lin JS, Parent MA, Mullarky‐Kanevsky I, Szaba FM, Kummer LW, Duso DK, Tighe M, Hill J, Gruber A, Mackman N, Gailani D, Smiley ST. Fibrin facilitates both innate and T cell‐mediated defense against Yersinia pestis . J Immunol 2013; 190: 4149–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Additional histologic sections of formalin‐fixed lungs stained with H&E from C57BL/6 or C57BL/6 PAI‐1 −/− mice inoculated with 104 CFUs of Y. pestis or Y. pestis Δpla.