Abstract

New N‐allyl/propargyl 4‐substituted 1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinolines derivatives were efficiently synthesized using acid‐catalyzed three components cationic imino Diels–Alder reaction (70–95%). All compounds were tested in vitro as dual acetylcholinesterase and butyryl‐cholinesterase inhibitors and their potential binding modes, and affinity, were predicted by molecular docking and binding free energy calculations (∆G) respectively. The compound 4af (IC 50 = 72 μ m) presented the most effective inhibition against acetylcholinesterase despite its poor selectivity (SI = 2), while the best inhibitory activity on butyryl‐cholinesterase was exhibited by compound 4ae (IC 50 = 25.58 μ m) with considerable selectivity (SI = 0.15). Molecular docking studies indicated that the most active compounds fit in the reported acetylcholinesterase and butyryl‐cholinesterase active sites. Moreover, our computational data indicated a high correlation between the calculated ∆G and the experimental activity values in both targets.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, cationic imino Diels–Alder reaction, cholinesterase inhibitors, docking and MM‐GBSA simulations, N‐Allyl/Propargyl tetrahydroquinolines

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most complex and common form of dementia in elderly people.

It is a neurodegenerative disease that causes progressive damage to the central nervous system, and is manifested with a cognitive deterioration, changes in brain function, including disordered behavior and impairment in language and comprehension 1. Currently, it is estimated that AD appears as the fourth leading cause of death afflicting more than seven million people worldwide 2.

According to the cholinergic hypothesis for AD pathogenesis, the decline of hippocampal and cortical levels of acetylcholine (ACh) leads to dysfunction of the cholinergic system and results in severe memory and learning deficits 3. At the neuronal level, ACh can be degraded by acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), being the predominant AChE (80%). Therefore, it is important to know that the use of different biological entities, which are involved in the same pathology (AChE and BChE), is widely accepted and can be a good strategy to block the course of multifactorial diseases rather than just reducing their symptoms 4.

Acetylcholinesterase and BChE share 65% amino acid sequence homology and, even though being encoded by different genes on human chromosomes 5, both enzymes display a similar overall structure. Therefore, their active sites, composed of a catalytic triad and a choline‐binding pocket, are both buried at the bottom of a ∼20 Å deep gorge. The two enzymes differ by the presence and extent of subdomains within the gorge, including a mid‐gorge aromatic recognition site, a peripheral anionic site, and an acyl‐binding site 6.

On the other hand, many kinds of heterocyclic derivatives have been reported with potent AChE and BChE inhibitory activity 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. However, many of them have showed adverse effects and problems of bioavailability12, 13. Therefore, it is necessary to develop new, safe, and efficient chemotherapeutic agents with potential applications for the treatment of AD.

Because of their remarkable biological applications, natural and synthetic quinoline compounds and their partially reduced derivatives, tetrahydroquinoline, are heterocycles of great relevance in medicinal chemistry and constitute an important class of compounds for new drug development 14. Compounds containing quinoline structure are widely used as antiasthmatic, antimalarial, antiviral, anti‐inflammatory, anti‐bacterial, antifungal, and anticancer drugs 15.

Different routes are used to carry out the synthesis of tetrahydroquinolines compounds 16, 17, 18. However, imino Diels–Alder reaction between aldimines and electron‐rich alkenes is probably the most powerful synthetic tool for the construction of these type of heterocyclic compounds 19. Diverse Lewis and Brønsted acids have been used as efficient catalysts for the synthesis of tetrahydroquinolines 20. When substituted anilines and formaldehyde are used as starting materials, a cationic 2‐azadiene intermediate is generated in situ. This cationic version of the imino Diels–Alder reaction, considered a formal inverse electron demand [4π + + 2π] cycloaddition reaction, has not been widely explored in the preparation of tetrahydroquinolines 21, 22. On the other hand, several bioactive compounds against neurodegenerative diseases, with allyl and propargyl fragments in their molecular structure, have been reported. Among them, propargylamine derivatives showed activity against monoamine oxidase 23 and cysteine derivatives with allyl group showed activity and high selectivity against BChE 24.

In the course of our screening for novel and selective bioactive compounds, we have reported the antiparasitic and antifungal activity of some substituted (tetrahydro) quinolines 25, 26, 27, 28. Considering our previous findings and continuing with our research effort in the search for new bioactive compounds, we decided to prepare different polyfunctionalized N‐allyl/propargyl 1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinolines and to evaluate their biological properties. Here, we report the synthesis and in vitro activity testing of several N‐allyl/propargyl 4‐substituted 1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline derivatives (4aa‐af) and (4ba‐bf), as dual AChE–BChE inhibitors, using N‐allyl/propargylanilines 1 as precursors. These tetrahydroquinoline compounds were prepared using a three‐component cationic imino Diels–Alder cycloaddition methodology 29 that provided the N‐allyl/propargyl 4‐substituted 1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline derivatives with high structural diversity. These new derivatives are potential cholinesterase inhibitors, which could be employed in the design of new drugs for AD treatments.

Methods and Materials

Chemistry

All reagents were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), J.T. Baker (Center Valley, PA, USA) and Sigma and Aldrich Chemical Co. (San Luis, MO, USA), and they were used without further purification. The reaction progress was monitored using thin layer chromatography on PF254 TLC aluminum sheets from Merck. Column chromatography was performed using Silica gel (60–120 mesh) and solvents employed were of analytical grade. The melting points (uncorrected) were determined using a Fisher‐Johns melting point apparatus (Bibby Scientific Limited, Staffordshire, UK). IR spectra were recorded on a FT‐IR Bruker Tensor 27 spectrophotometer coupled to Bruker platinum ATR cell. Mass spectrometry ESI‐MS analyses were conducted on an ESI‐IT Amazon X (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) with direct injection, operating in Full Scan at 300 °C and 4500V in the capillary, using nitrogen as nebulizer gas with a flow of 8 L/min and 30 psi. The elemental analysis of the different compounds was performed in a Thermo Scientific CHNS‐O analyzer equipment (Model. Flash 2000, Waltham, MA, USA).

NMR spectra (1H and 13C) were measured on a Bruker Ultrashield‐400 spectrometer (400 MHz 1H NMR and 100 MHz 13C NMR), using CDCl3 as solvent and TMS as reference. J values are reported in Hz; chemical shifts are reported in p.p.m. (δ) relative to the solvent peak (residual CHCl3 in CDCl3 at 7.26 p.p.m. for protons). Signals were designated as follows: s, singlet; d, doublet; dd, doublet of doublets; ddd, doublet of doublets of doublets; ddt, doublet of doublets of triplets; t, triplet; td, triplet of doublets; q, quartet; m, multiplet; and br., broad.

General procedure for the synthesis of N‐allyl/propargyl‐4‐(2‐oxopyrrolidin‐1‐yl)‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinolines

All reactions were performed at room temperature unless otherwise stated. In a round bottom flask, a 5 mL solution in acetonitrile (MeCN) HPLC grade of preformed N‐allylaniline (1a) or N‐propargylaniline (1b) (1 mmol) and formaldehyde (2, 37% in methanol; 1.1 mmol) was prepared and stirred for 10 min. A 5 mL solution of p‐TsOH (InCl3) (20 mol%) in MeCN was then added. After 20 min a solution of N‐vinyl‐2‐pyrrolidinone 3 (1.1 mmol) in MeCN was incorporated to the reaction mixture and was vigorously stirred. The resulting mixture was stirred for 3–4 h. After completion of the reaction as indicated by TLC, the reaction mixture was diluted with water (30 mL) and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 15 mL). The organic layer was separated and dried (Na2SO4). The crude product was obtained by solvent removal under vacuum and then purified by column chromatography, eluted with the appropriate mixture of petroleum ether and ethyl acetate to afford pure tetrahydroquinolines 4.

N‐allyl‐4‐(2′‐oxopyrrolidin‐1′‐yl)‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline (4aa)

Viscous yellow oil. Yield 80%. IR (ATR): 1668.5, 1605.4, 1510.6, 910.1 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 1.49‐ 1.43 (2H, m, 3‐H), 1.99–1.84 (2H, m, 4′‐H), 2.44–2.32 (2H, m, 3′‐H), 3.05–2.97 (1H, m, 5′‐Hb), 3.30–3.25 (1H, m, 5′‐Ha), 3.35–3.30 (1H, m, 2‐Hb), 3.45–3.37 (1H, m, 2‐Ha), 3.93–3.90 (2H, m, 11‐H), 5.21–5.13 (2H, m, 9‐H), 5.38 (1H, q, J = 7.2 Hz, 4‐H), 5.84 (1H, ddt, J = 17.1, 10.0, 4.9 Hz, 10‐H), 6.60 (1H, dd, J = 8.8, 3.1 Hz, 8‐H), 7.04–7.07 (1H, m, 5‐H), 7.12 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, 7‐H), 7.31–7.28 (1H, m, 6‐H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 174.5, 147.9, 133.9, 128.6, 127.9, 123.8, 118.2, 116.1, 112.1, 52.8, 48.4, 46.4, 42.3, 31.7, 18.1, 16.5. MS (ESI‐IT), m/z: 257.3 [M + H]+, 279.1 [M + Na]+, 535.2 [2M + Na]+, 172.4 [(M + H)‐C4H6NO]+. Anal. Calcd for C16H20N2O: C, 74.97; H, 7.86; N, 10.93%. Found: C, 74.82; H, 7.79; N, 10.78%.

N‐allyl‐6‐methyl‐4‐(2′‐oxopyrrolidin‐1′‐yl)‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline (4ab)

Dark red oil. Yield 77%. IR (ATR): 1674.3, 1617.6, 1506.2, 917.0 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 2.03–1.94 (2H, m, 3‐H), 2.13–2.04 (2H, m, 4′‐H), 2.17 (3H, s, 6‐CH3), 2.52–2.37 (2H, m, 3′‐H), 3.17–3.10 (1H, m, 5′‐Hb), 3.26–3.18 (2H, m, 2‐Hb, 5′‐Ha), 3.37–3.30 (1H, m, 2‐Ha), 3.83 (2H, m, 11‐H), 5.20–5.12 (2H, m, 9‐H), 5.33 (1H, dd, J = 9.5, 5.5 Hz, 4‐H), 5.81 (1H, ddt, J = 17.2, 10.3, 5.2 Hz, 10‐H), 6.46 (1H, d, J = 2.8 Hz, 8‐H), 6.58 (1H, d, J = 8.9 Hz, 5‐H), 6.69 (1H, dd, J = 8.9, 3.0 Hz, 7‐H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 175.5, 143.9, 133.3, 129.2, 128.3, 125.5, 119.4, 116.5, 112.2, 54.1, 48.1, 47.1, 43.9, 31.6, 26.9, 20.4, 18.8. MS (ESI‐IT), m/z: 271.1 [M + H]+, 293.0 [M + Na]+, 563.1 [2M + Na]+, 186.1 [(M + H)‐C4H6NO]+.Anal. Calcd for C17H22N2O: C, 75.52; H, 8.20; N, 10.36%. Found: C, 75.38; H, 8.11; N, 10.25%.

N‐allyl‐6‐methoxy‐4‐(2′‐oxopyrrolidin‐1′‐yl)‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline (4ac)

Viscous orange oil; Yield 84%. IR (ATR): 1662.6, 1597.2, 1503.0, 923.2 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 2.03–1.92 (2H, m, 3‐H), 2.11–2.04 (2H, m, 4′‐H), 2.52–2.35 (2H, m, 3′‐H), 3.18–3.12 (1H, m, 5′‐Hb), 3.26–3.19 (2H, m, 2‐Hb, 5′‐Ha), 3.35–3.27 (1H, m, 2‐Ha), 3.70 (3H, s, 6‐CH3O), 3.81 (2H, m, 9‐H), 5.20–5.12 (2H, m, 11‐H), 5.36 (1H, dd, J = 9.4, 5.6 Hz, 4‐H), 5.82 (1H, ddt, J = 17.1, 10.4, 5.3 Hz, 10‐H), 6.46 (1H, d, J = 2.8 Hz, 8‐H), 6.58 (1H, d, J = 8.9 Hz, 5‐H), 6.69 (1H, dd, J = 8.9, 3.0 Hz, 7‐H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 175.7, 151.3, 140.5, 133.5, 121.0, 116.6, 114.1, 113.7, 113.3, 55.8, 54.5, 48.2, 47.3, 43.6, 31.5, 26.8, 18.3. MS (ESI‐IT), m/z: 287.1 [M + H]+, 309.0 [M + Na]+, 595.1 [2M + Na]+, 202.0 [(M + H)‐C4H6NO]+. Anal. Calcd for C17H22N2O2: C, 71.30; H, 7.74; N, 9.78%. Found: C, 71.19; H, 7.61; N, 9.67%.

N‐allyl‐6‐chloro‐4‐(2′‐oxopyrrolidin‐1′‐yl)‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline (4ad)

Viscous red oil. Yield 93%. IR (ATR): 1673.4, 1596.2, 1495.6, 919.5 cm1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 2.04–1.94 (2H, m, 3‐H), 2.16–2.04 (2H, m, 4′‐H), 2.57–2.42 (2H, m, 3′‐H), 3.19–3.12 (1H, m, 5′‐Hb), 3.24–3.20 (1H, m, 5′‐Ha), 3.28–3.24 (1H, m, 2‐Hb), 3.44–3.37 (1H, m, 2‐Ha), 3.84 (2H, m, 9‐H), 5.19–5.11 (2H, m, 11‐H), 5.34 (1H, dd, J = 9.6, 5.4 Hz, 4‐H), 5.78 (1H, ddt, J = 15.8, 10.9, 5.2 Hz, 10‐H), 6.48 (1H, d, J = 8.9 Hz, 8‐H), 6.79 (1H, dd, J = 2.6, 1.0 Hz, 5‐H), 7.01 (1H, ddd, J = 8.8, 2.6, 0.7 Hz, 7‐H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 175.7, 144.5, 132.6, 128.4, 127.1, 121.1, 120.9, 116.7, 113.2, 54.3, 47.9, 47.3, 43.6, 31.4, 26.4, 18.5. MS (ESI‐IT), m/z: 291.0 [M + H]+, 313.0 [M + Na]+, 603.0 [2M + Na]+, 206.2 [(M + H)‐C4H6NO]+. Anal. Calcd for C16H19ClN2O: C, 66.09; H, 6.59; N, 9.63%. Found: C, 65.98; H, 6.53; N, 9.48%.

N‐allyl‐6‐ethyl‐4‐(2′‐oxopyrrolidin‐1′‐yl)‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline (4ae)

Viscous yellow oil. Yield 74%. IR (ATR): 1676.1, 1617.3, 1508.2, 920.6 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 1.24 (3H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, CH3), 2.01–1.94 (2H, m, 4′‐H), 2.14–2.02 (2H, m, 3‐H), 2.52–2.40 (4H, m, 3′‐H, –CH2–), 3.16–3.10 (1H, m, 5′‐Hb), 3.24–3.19 (2H, m, 2‐Hb, 5′‐Ha), 3.37–3.31 (1H, m, 2‐Ha), 3.85–3.80 (2H, m, 9‐H), 5.21–5.12 (2H, m, 11‐H), 5.36 (1H, dd, J = 8.8, 5.6 Hz, 4‐H), 5.82 (1H, ddt, J = 17.2, 10.3, 5.2 Hz, 10‐H), 6.54 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, 8‐H), 6.68 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz, 5‐H), 6.92 (1H, dd, J = 8.4, 2.2 Hz, 7‐H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 175.4, 144.1, 133.4, 132.2, 127.9, 127.2, 119.4, 116.5, 112.2, 54.2, 48.2, 47.1, 43.9, 31.6, 27.9, 26.9, 18.7. MS (ESI‐IT), m/z: 285.3 [M + H]+, 307.1 [M + Na]+, 591.2 [2M + Na]+, 200.3 [M‐C4H6NO]+. Anal. Calcd for C18H24N2O: C, 76.02; H, 8.51; N, 9.85%. Found: C, 75.91; H, 8.42; N, 9.68%.

N‐allyl‐6‐fluor‐4‐(2′‐oxopyrrolidin‐1′‐yl)‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline (4af)

Viscous yellow oil. Yield 85%. IR (ATR): 1675, 1615, 1504, 921 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 2.04–1.96 (2H, m, 4′‐H), 2.16–2.05 (2H, m, 3‐H), 2.52–2.47 (2H, m, 3′‐H, –CH2), 3.19–3.11 (1H, m, 5′‐Hb), 3.29–3.20 (2H, m, 2‐Hb, 5′‐Ha), 3.41–3.34 (1H, m, 2‐Ha), 3.87 (1H, ddt, J = 17.0, 5.0, 1.6 Hz, 9‐Hb), 3.87 (1H, ddt, J = 17.0, 5.0, 1.6 Hz, 9‐Ha), 5.21–5.12 (2H, m, 11‐H), 5.37 (1H, dd, J = 8.8, 5.6 Hz, 4‐H), 5.80(1H, ddt, J = 17.2, 10.3, 5.1 Hz, 10‐H), 6.50 (1H, d, J = 8.6 Hz, 8‐H), 6.58 (1H, ddd, J = 9.2, 3.0, 1.0 Hz, 5‐H), 6.82–6.76 (1H, m, 7‐H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 175.8, 155.2 (d, J = 238.3 Hz), 142.6, 132.5, 121.1 (d, J = 6.0 Hz), 116.8, 115.2 (d, J = 22.7 Hz), 113.6 (d, J = 22.7 Hz), 113.1 (d, J = 6.9 Hz), 54.5, 48.2, 47.5, 43.5, 31.4, 26.6, 18.4. MS (ESI‐IT), m/z: 275.3 [M + H]+, 297.1 [M + Na]+, 571.1 [2M + Na]+, 190.3 [M‐C4H6NO]+. Anal. Calcd for C16H19FN2O: C, 70.05; H, 6.98; N, 6.93%. Found: C, 69.95; H, 6.90; N, 10.04%.

N‐allyl‐6‐bromo‐4‐(2′‐oxopyrrolidin‐1′‐yl)‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline (4ag)

Viscuous red oil. Yield 89%. IR (ATR): 1668.25, 1589.39, 1499.20, 922.51 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 2.04–1.94 (2H, m, 3‐H), 2.13–2.04 (2H, m, 4′‐H), 2.55–2.44 (2H, m, 3′‐H), 3.19–3.13 (1H, m, 5′‐Hb), 3.24–3.20 (1H, m, 5′‐Ha), 3.28–3.24 (1H, m, 2‐Hb), 3.44–3.37 (1H, m, 2‐Ha), 3.81 (2H, dd, J = 17.7, 4.9 Hz, 11‐Hb), 3.86 (1H, dd, J = 17.7, 4.9 Hz, 11‐Ha), 5.21–5.12 (2H, m, 11‐H), 5.34 (1H, dd, J = 9.2, 5.4 Hz, 4‐H), 5.79 (1H, ddd, J = 16.0, 10.2, 4.9 Hz, 10‐H), 6.44 (1H, d, J = 8.9 Hz, 8‐H), 6.92 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz, 5‐H), 7.14 (1H, dd, J = 8.8, 2.2 Hz, 7‐H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 175.6, 145.1, 132.5, 131.4, 129.9, 121.5, 116.75, 113.7, 108.2, 53.9, 48.2, 47.1, 43.8, 31.5, 26.5, 18.4. MS (ESI‐IT), m/z: 358.8 [M + Na]+. Anal. Calcd for C16H17BrN2O: C, 57.32; H, 5.71; N, 8.36%. Found: C, 57.25; H, 5.64; N, 8.21%.

N‐propargyl‐4‐(2′‐oxopyrrolidin‐1′‐yl)‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline (4ba)

Light yellow solid. Yield 73%. m.p. 88–90 °C; IR (ATR): 3224.0, 2962.7, 2929.4, 2912.5, 2856.1, 1663.3, 1420.8, 1332.6, 1191.8, 751.2 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 1.95–2.03 (2H, m, 4′‐H), 2.06–2.20 (2H, m, 3‐H), 2.15 (1H, t, J = 2.48, 13‐H), 2.44–2.50 (2H, m, 3′‐H), 3.06–3.26 (2H, m, 5′‐H), 3.27–3.43 (2H, m, 2‐H), 3.96 (1H, dd, J = 18.1, 2.4 Hz, 11‐Ha), 4.06 (1H, dd, J = 18.1, 2.4 Hz, 11‐Hb), 5.40 (1H, dd, J = 9.0, 8.8 Hz, 4‐H), 6.72 (1H, dd, J = 7.4, 1.0 Hz, 6‐H), 6.76 (1H, d, J = 8.9 Hz, 8‐H), 6.90 (1H, dt, J = 7.6, 1.2 Hz, 5‐H), 7.16 (1H, tdd, J = 8.9, J = 1.7, 0.6 Hz, 7‐H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 175.54, 145.37, 128.59, 128.08, 121.11, 118.23, 112.98, 79.11, 72.15, 47.83, 47.51, 43.83, 40.92, 31.57, 26.80, 18.37. MS (ESI‐IT), m/z: 170.0 [M‐C4H7NO]+, 277.1[M + Na]+, 531.1[2M + Na]+. Anal. Calcd for C16H18N2O: C, 75.56; H, 7.13; N, 11.01%. Found: C, 75.47; H, 7.04; N, 10.82%.

N‐propargyl‐6‐methyl‐4‐(2′‐oxopyrrolidin‐1′‐yl)‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline (4bb)

Yellow Solid. Yield 95%. m.p. 125–127 °C; IR (ATR): 3212.4, 2951.6, 2890.3, 2097.7, 1667.2, 1500.4, 1332.6, 807.6, 707.3 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 1.92–2.04 (2H, m, 4′‐H), 2.05–2.19 (2H, m, 3‐H), 2.14 (1H, t, J = 2.3 Hz, 13‐H), 2.21 (3H, s, 6‐CH3), 2.49 (2H, td, J = 8.1, 2.4 Hz, 3′‐H), 3.07–3.29 (2H, m, 5′‐H), 3.20–3.38 (2H, m, 2‐H), 3.95 (1H, dd, J = 18, 2.4 Hz, 11‐Ha), 4.04 (1H, dd, J = 18, 2.4 Hz, 11‐Hb), 5.38 (1H, dd, J = 8.7, 8.2 Hz, 4‐H), 6.68 (1H, d, J = 8.3 Hz, 8‐H), 6.72 (1H, s, 5‐H), 6.98 (1H, ddd, J = 8.3, 1.5, 0.6 Hz, 7‐H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 175.53, 143.21, 129.21, 128.7, 127.66, 121.27, 113.3, 79.20, 72.18, 47.77, 47.61, 43.9, 41.12, 31.63, 27.05, 20.54, 18.42. MS (ESI‐IT), m/z: 291.1[M + Na]+, 531.1[2M‐CH3 + Na]+, 559.1[2M + Na]+. Anal. Calcd for C17H20N2O: C, 76.09; H, 7.51; N, 10.44%. Found: C, 75.98; H, 7.41; N, 10.28%.

N‐propargyl‐6‐methoxy‐4‐(2′‐oxopyrrolidin‐1′‐yl)‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline (4bc)

Brown Solid. Yield 92%. m.p. 154–156 °C; IR (ATR): 3263.5, 2956.1, 2934.2, 2873.5, 2807.9, 1671.5, 1498.0, 1059.7, 802.7 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 1.92–2.04 (2H, m, 4′‐H), 2.05–2.16 (2H, m, 3‐H), 2.14 (1H, t J = 2.4 Hz, 13‐H), 2.46–2.50 (2H, m, Hz, 3′‐H), 3.09–3.3 (2H, m, 5′‐H), 3.18–3.35 (2H, m, 2‐H), 3.71 (3H, s, 6‐OCH3), 3.91 (1H, dd, J = 18.1, 2.4 Hz, 11‐Ha), 4.04 (1H, dd, J = 18.1, 2.4 Hz, 11‐Hb), 5.40 (1H, dd, J = 8.8, 6.4 Hz, 4‐H), 6.51 (1H, d, J = 2.8 Hz, 8‐H), 6.72 (1H, d, J = 8.9 Hz, 5‐H), 6.77 (1H, ddd, J = 8.9, 2.8, 0.4 Hz, 7‐H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 175.58, 152.53, 139.76, 122.91, 114.61, 114.06, 113.68, 79.2, 72.33, 55.77, 48.00, 47.85, 43.7, 41.48, 31.55, 26.98, 18.42. MS (ESI‐IT), m/z: 307.1[M + Na]+, 591.1[2M + Na]+. Anal.Calcd for C17H20N2O2: C, 71.81; H, 7.09; N, 11.25%. Found: C, 71.72; H, 7.01; N, 11.06%.

N‐propargyl‐6‐chloro‐4‐(2′‐oxopyrrolidin‐1′‐yl)‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline (4bd)

Yellow Solid. Yield 91%. m.p. 123–125 °C; IR (ATR): 3209.0, 2954.5, 2932.8, 2887.4, 2846.0, 1670.6, 1488.8, 1422.3, 1164.4, 809.5 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 1.97–2.06 (2H, m, 4′‐H), 2.06–2.17 (2H, m, 3‐H), 2.16 (1H, t, J = 2.4 Hz, 13‐H), 2.48 (2H, m, 3′‐H), 3.09–3.28 (2H, m, 5′‐H), 3.24–3.43 (2H, m, 2‐H), 3.92 (1H, dd, J = 18.3, 2.3 Hz, 11‐Ha), 4.04 (1H, dd, J = 18.3, 2.3 Hz, 11‐Hb), 5.36 (1H, dd, J = 9.2, 9.1 Hz, 4‐H), 6.67 (1H, d, J = 8.9 Hz, 8‐H), 6.85 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 0.7 Hz, 5‐H), 7.10 (1H, dd, J = 8.9, 2.6 Hz, 7‐H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 175.60, 143.97, 128.45, 127.43, 123.11, 122.94, 114.34, 78.62, 72.46, 47.61, 47.59, 43.57, 41.04, 31.4, 26.52, 18.35, MS (ESI‐IT), m/z: 311.1[M + Na]+, 599.1 [2M + Na]+, 886.2[3M + Na]+. Anal. Calcd forC16H17ClN2O: C, 66.55; H, 5.93; N, 9.70%. Found: C, 66.48; H, 5.87; N, 12.08%.

N‐propargyl‐6‐ethyl‐4‐(2′‐oxopyrrolidin‐1′‐yl)‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline (4be)

White Solid. Yield 91%. m.p. 106–107 °C; IR (ATR): 3224.9, 2958.7, 2931.7, 2895.1, 1668.4, 1492.9, 1157.3 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 1.15 (3H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, –CH3), 1.9–2.02 (2H, m, 4′‐H), 2.03–2.16 (2H, m, 3‐H), 2.14 (1H, t, J = 2.3 Hz, 13–H), 2.44–2.55 (4H, m, 3′‐H, –CH2–), 3.06–3.23 (2H, m, 5′‐H), 3.24–3.38 (2H, m, 2‐H), 3.95 (1H, dd, J = 18.2, 2.3 Hz, 11‐Ha), 4.03 (1H, dd, J = 18.2, 2.3 Hz, 11‐Hb), 5.38 (1H, dd, J = 8.2, 6.4 Hz, 4‐H), 6.70 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, 8‐H), 6.73 (1H, d, J = 1.7 Hz, 5‐H), 7.00 (1H, dd, J = 8.4, 1.7 Hz, 7‐H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 175.48, 143.32, 134.08, 127.92, 127.48, 121.07, 113.15, 79.22, 72.13, 47.81, 47.50, 43.90, 41.01, 31.6, 26.99, 27.88, 18.43, 15.92. MS (ESI‐IT), m/z: 305.1[M + Na]+, 587.1[2M + Na]+. Anal.Calcd for C18H22N2O: C, 76.56; H, 7.85; N, 9.92%. Found: C, 76.42; H, 7.75; N, 9.78%.

N‐propargyl‐6‐fluor‐4‐(2′‐oxopyrrolidin‐1′‐yl)‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline (4bf)

White Solid. Yield 85%. m.p. 131–132 °C; IR (ATR): 3302.0, 2935.6, 2954.9, 2812.1, 1670.3, 1500.6, 1421.5, 1190.0 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 1.95–2.04 (2H, m, 4′‐H), 2.05–2.13 (2H, m, 3‐H), 2.14–2.16 (1H, m, 13‐H), 2.47 (2H, m, 3′‐H), 3.07–3.22 (2H, m, 5′‐H), 3.24–3.39 (2H, m, 2‐H), 3.88 (1H, dd, J = 18.2, 2.4 Hz, 11‐Ha), 4.04 (1H, dd, J = 18.2, 2.4 Hz, 11‐Hb), 5.38 (1H, dd, J = 9.2, 6.8 Hz, 4‐H), 6.61 (1H, ddd, J = 9.1, 3.1, 1.0 Hz, 5‐H), 6.67 (1H, dd, J = 9.1, 4.6 Hz, 8‐H), 6.85 (1H, tdd, J = 8.5, 3.1, 0.8 Hz, 7‐H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 175.59, 156.0 (d, J = 237 Hz), 141.7 (d, J = 2 Hz,), 123.0 (d, J = 6 Hz), 115.0 (d, J = 12 Hz), 114.2 (d, J = 22 Hz), 114.0 (d, J = 22.2 Hz), 78.77, 72.41, 47.79, 47.74, 43.36, 41.31, 31.34, 26.53, 18.26. MS (ESI‐IT), m/z: 295.1[M + Na]+, 567.0[2M + Na]+. Anal. Calcd for C16H17FN2O: C, 70.57; H, 6.29; N, 10.29%. Found: C, 70.49; H, 6.21; N, 10.12%.

N‐propargyl‐6‐bromo‐4‐(2′‐oxopyrrolidin‐1′‐yl)‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline (4bg)

Yellow solid. Yield 93%. m.p. 118–120 °C; IR (ATR): 3223.5, 2950.6, 2925.2, 2877.4, 1681.7, 1484.7 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 1.97–2.03 (2H, m, 4′‐H), 2.03–2.15 (2H, m, 3‐H), 2.16 (1H, t, J = 2.1 Hz, 13‐H), 2.47 (2H, m, 3′‐H), 3.06–3.24 (2H, m, 5′‐H), 3.26–3.44 (2H, m, 2‐H), 3.92 (1H, dd, J = 18.0, 2.4 Hz, 11‐Ha), 4.02 (1H, dd, J = 18.0, 2.4 Hz, 11‐Hb), 5.35 (1H, dd, J = 9.2, 6.0 Hz, 4‐H), 6.61 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, 8‐H), 6.97 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, 5‐H), 7.22 (1H, dd, J = 8.8, 2.4 Hz, 7‐H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (p.p.m.): 175.55, 144.43, 131.35, 130.32, 123.36, 114.47, 110.23, 78.59, 72.46, 47.59, 47.49, 43.66, 40.97, 31.39, 26.55, 18.38. MS (ESI‐IT), m/z: 249.0[M‐C4H7NO]+, 356.9[M + Na]+. Anal. Calcd for C16H17BrN2O: C, 57.67; H, 5.14; N, 8.41%. Found: C, 57.58; H, 5.07; N, 8.28%.

Cholinesterase inhibition

The biological evaluation of synthesized compounds, as cholinesterase inhibitors, was performed using the methodology described by Ellmann 30. In a 96‐well plate, 50 μL of the sample dissolved in phosphate buffer (8 mmol/L K2HPO4, 2.3 mmol/L NaH2PO4, 150 mmol/L NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20 at pH 7.6) as well as 50 μL of the AChE/BChE solution (0.25 unit/mL), from Electrophorus electricus/Bovine serum in the same phosphate buffer, were added. The assay solutions, except the substrate, were pre‐incubated with the enzyme for 30 min at room temperature. After pre‐incubation the substrate was added. The substrate solution consists of Na2HPO4 (40 mmol/L), acetylthiocholine/butyrylthiocholine (0.24 mmol/L), and 5,5′‐dithio‐bis‐(2‐nitrobenzoic acid) (0.2 mmol/L, DTNB, Ellman's reagent). The absorbance of the yellow anion product, due to the spontaneous hydrolysis of substrate, was measured at 405 nm for 5 min on a Microtiter plate reader (Multiskan EX, Thermo, Vantaa, Finland). The AChE/BChE inhibition was determined for each compound. The enzyme activity was calculated as a percentage, compared against a control containing only the buffer and the enzyme in solution. The compounds were assayed in the dilution interval of 15–500 μg/mL and the alkaloid galantamine was used as the reference compound. Each assay was run in triplicate and each reaction was repeated at least three independent times. The IC50 values were calculated by means of regression analysis.

Enzymatic kinetic study

For enzymatic kinetic studies, the enzyme was pre‐incubated with different substrate concentrations ranging from 9.38 × 10−4 to 0.48 mm. For the determination of type of inhibition, V max and K m (Michaelis constant), double reciprocal plots (1/V versus 1/[S] where V = reaction rate and S = substrate concentration) were constructed, using Lineweaver–Burk methods. Determinations were made in the absence and presence of test compounds. At least three different concentrations of test compound were used in each instance and the experiment was performed in triplicate. Data analysis was carried out with sigmaplot v10.0 and enzyme kinetic v1.3 add‐on (Systat Software, Inc, Richmond, CA, USA)1 .

Computational studies

Molecular docking

The computational process of searching for a ligand that is able to fit both, geometrically and energetically, the binding site of a protein is called molecular docking 31. Docking studies were performed using glide.2 Glide uses a series of hierarchical filters to find the best possible ligand binding locations in a protein grid space previously built. The filters include a systematic searching approach, which samples the positional, conformational, and orientation space of the ligand before evaluating the energy interactions of the ligand with the protein (in our case AChE and BChE). The atomic coordinates for proteins were extracted from the X‐ray crystal structures of AChE (PDB ID: 1E66) 32 and BChE (PDB ID: 4BDS) 33. The AChE and BChE protein structures, employed for molecular docking and ∆G calculations, were prepared using the Protein Preparation Wizard module from maestro suite 2. The center of the grid box was located into the residues Phe330, Trp84 for AChE; and Trp82 for BChE; the outer box edge of the grid box was refined and setting up as 30Å. The docking was carried out using the standard precision algorithm implemented in Glide.

The docking hierarchy begins with the systematic conformational expansion of the ligand, followed by the placement in the protein site. Then, minimization of the ligand in the field of the protein is carried out using the OPLS‐AA 34 force field with a distance‐dependent dielectric 2.0. Subsequently, the lowest energy poses are subjected to a Monte Carlo (MC) procedure that samples nearby torsional minima. The best pose for a given ligand is determined by the Emodel score while different compounds are ranked using Glide Score (a modified version of the Chem Score function of Eldridge 35 that includes terms for buried polar groups and steric clashes. In total 56 docking simulations, 28 for ligand‐AChE and 28 for ligand‐BChE, that included the two compound's isomers, were performed. The top‐10 conformational poses for each complex were selected to estimate the ∆G bind through MM‐GBSA method; corrections for entropy changes were not applied because we use congeneric THQs series.

Binding free energy calculations

The computational method Molecular Mechanics‐Generalized Born Surface Area (MM‐GBSA)was employed using Prime2. This method combines molecular mechanics energy and implicit solvation models 36, and it was applied after the molecular docking process to re‐score the N‐allyl/propargyltetrahydroquinoline molecules and to obtain a more accurate estimation of ∆G bind values. In MM‐GBSA, ∆G bindin the complex between ligands and the protein is calculated as:

where ΔG bind is the binding free energy (kcal/mol), ΔH corresponding to the enthalpy and ΔE MM, ΔG sol and TΔS are the changes in the Molecular Mechanics Energy, the solvation free energy and the conformational entropy upon binding, respectively 37. This last term was not considered in our ∆G bind calculations.

To perform the MM‐GBSA calculations, the solvation model VSGB 38 and force field OPLS‐AA were employed. Residues at a distance at 5 Å from the ligands were included in the flexible region.

ADME screening

The absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties of the molecules were obtained by Qik Propprogram 39; to predict some physical and pharmaceutical properties. For this purpose, 44 descriptors were predicted for the set of new ligands, such as molecular weight, molecular volume, van der Waals, surface areas of polar nitrogen and oxygen atoms, H bond acceptors, H bond donors, Log P (octanol/water), rotatable bonds, among others. From these descriptors, qikprop software also evaluated the acceptability of the compounds based on Lipinski's rules 40.

Statistical analysis

All assays were performed in triplicate in independent assays, and obtained values were analyzed and expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) using Statistical Product and Service Solutions, 17th version (spss, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)). IC50 values for tetrahydroquinolines derivates against AChE were calculated using regression analysis. Statistical analyses were performed by one‐way analysis of variance (anova).

Results and Discussion

Chemistry

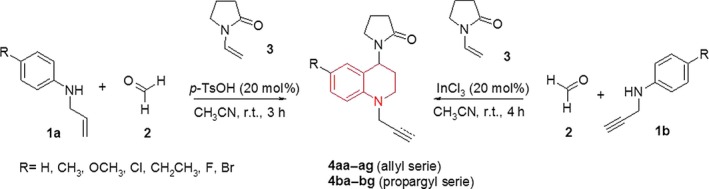

The synthesis of target N‐allyl/propargyl 4‐substituted 1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinoline derivatives 4 (allyl and propargyl series) was carried out using a straight forward and efficient synthesis based on the acid‐catalyzed one‐pot multicomponent cationic imino Diels–Alder reaction, outlined in Scheme 1. In the case of the synthesis of N‐allyl tetrahydroquinoline series (4aa‐ag), the reaction occurs in anhydrous MeCN between preformed N‐allylanilines 1a, formalin (37% formaldehyde) 2 and N‐vinyl‐2‐pyrrolidinone 3 in presence of p‐toluenesulfonic acid (p‐TsOH, 20% mol) as acid‐catalyst at room temperature. These tetrahydroquinoline derivatives (4aa‐ag) were obtained as viscous oils with 74–93% yield after their chromatography purification (Scheme 1, Table 1). Synthesis of N‐propargyl tetrahydroquinolines series (4ba‐bg) involved the reaction among preformed N‐propargylaniline1b, inexpensive formalin 2 and N‐vinyl‐2‐pyrrolidone 3. In this case the best performance of the reaction occurred when Indium (III) chloride (InCl3, 20% mol), in anhydrous MeCN at room temperature, was used as catalyst. After chromatography purification, the respective N‐propargyltetrahydroquinoline derivatives (4ba‐bg) were obtained as stable solids and with high yields (73–95%) (Scheme 1, Table 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of new N‐allyl/propargyl tetrahydroquinoline derivatives 4, via one‐pot three‐component cationic imino Diels–Alder reaction.

Table 1.

Physicochemical parameters obtained for new N‐allyl/propargyl tetrahydroquinolines 4

| Comp.a | R | N‐alkyl | M.W. (g/mol) | Time, h | Yield, % b | M.p., °Cc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4aa | H | CH2=CHCH2 | 256 | 3 | 80 | Yellow oil |

| 4ab | CH3 | CH2=CHCH2 | 270 | 3 | 77 | Dark red oil |

| 4ac | OCH3 | CH2=CHCH2 | 286 | 3 | 84 | Orange oil |

| 4ad | Cl | CH2=CHCH2 | 290 | 3 | 93 | Red oil |

| 4ae | CH2CH3 | CH2=CHCH2 | 284 | 3 | 74 | Yellow oil |

| 4af | F | CH2=CHCH2 | 274 | 3 | 85 | Yellow oil |

| 4ag | Br | CH2=CHCH2 | 335 | 3 | 89 | Red oil |

| 4ba | H | HC≡CCH2 | 254 | 4 | 73 | 88–90 |

| 4bb | CH3 | HC≡CCH2 | 268 | 4 | 95 | 125–127 |

| 4bc | OCH3 | HC≡CCH2 | 284 | 4 | 92 | 123–125 |

| 4bd | Cl | HC≡CCH2 | 288 | 4 | 91 | 154–156 |

| 4be | CH2CH3 | HC≡CCH2 | 282 | 4 | 91 | 106–107 |

| 4bf | F | HC≡CCH2 | 272 | 4 | 85 | 131–132 |

| 4bg | Br | HC≡CCH2 | 333 | 4 | 93 | 118–120 |

Compounds 4aa‐ag were obtained using InCl3 (20 mol%) as catalyst, while compounds 4ba‐bg were obtained by using p‐TsOH (20 mol%).

Yields after column chromatography.

Uncorrected.

All new N‐allyl/propargyltetrahydroquinoline derivatives 4 were structurally characterized using NMR spectroscopic techniques, electrospray ionization‐mass spectrometry (ESI‐MS) and IR spectroscopy. In the IR spectra, bands for C=O (1662 –1681 cm−1) vibrations were observed.

In the particular case of N‐allyl tetrahydroquinoline, IR spectra showed typical bands from allyl fragment (910–923 cm−1) vibrations, while that in the IR spectra for N‐propargyltetrahydroquinoline was easily identified as bands for propargyl fragment (3209–3302 cm−1) vibrations. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectroscopy in CDCl3 solution was carried out and all the signals for each individual H– and C–atoms (see experimental section) were unambiguously assigned on the basis of their COSY, HSQC, and HMBC spectra, as well as by comparing them against the reference spectra of previously reported analogues. All 1H NMR spectra of the synthesized N‐allyl/propargyl tetrahydroquinolines were very similar and characterized by the presence of three groups of signals. A first group of signals between 7.30–6.40 p.p.m., indicating the presence of aromatic protons, was observed. Similarly, it was also possible to observe the tetrahydroquinoline proton signals around 5.40–2.00 p.p.m. Finally, in the 3.30–1.80 p.p.m. region we observed various multiplets corresponding to the proton signals of the 2‐pyrrolidone fragment. Spectroscopic analyses of 1H NMR spectra allowed us to identify the characteristic signals for allyl and propargyl fragments in the tetrahydroquinoline. In all cases, doublets of doublet around 5.79–5.84 p.p.m. were observed. Furthermore, the 13C NMR spectrum, for all compounds, showed the aliphatic carbons appearing between 16.5–55.8 p.p.m., aromatic carbons between 108.1–147.9 p.p.m., and the characteristic C=O signal appearing around 174.5–175.7 p.p.m. This set of signals constitutes evidence that the cationic imino Diels–Alder reaction took place successfully.

Anti‐cholinesterase biological activities

All synthesized compounds were evaluated in vitro as dual AChE/BChE inhibitors. The compound's concentration required for 50% of enzyme inhibition (IC50) was calculated by means of regression analysis.

All tabulated results in Table 2 are expressed in μ m as means ± SEM, and they were compared using anova analysis. A p value, <0.05, was considered significant. Details for pharmacological experiments are described in Experimental section as well as in previous reports 41. Although the biological activity of compounds was poor, when compared to the reference employed, it was proved that synthesized compounds could be starting scaffolds used as interesting pharmacophores for the design of new biologically active compounds against enzymes related with neurodegenerative diseases. The N‐allyl tetrahydroquinolines exhibited promising inhibitory activity on both AChE/BChE enzymes.

Table 2.

Structure of synthetic compounds and their cholinesterase activities over acetylcholinesterase (AChE) from Electrophorus electricus and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) from equine serum

| Comp. | R | N‐alkyl | AChE (μ m)a | BChE (μ m)a | SIb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4aa | H | CH2=CHCH2 | 211.72 ± 0.02 | 456.95 ± 0.03 | 2.16 |

| 4ab | CH3 | CH2=CHCH2 | 75.17 ± 0.01 | 31.66 ± 0.01 | 0.42 |

| 4ac | OCH3 | CH2=CHCH2 | 75.10 ± 0.01 | 62.23 ± 0.02 | 0.83 |

| 4ad | Cl | CH2=CHCH2 | 293.52 ± 0.02 | 62.26 ± 0.08 | 0.21 |

| 4ae | CH2CH3 | CH2=CHCH2 | 173.96 ± 0.02 | 25.58 ± 0.02 | 0.15 |

| 4af | F | CH2=CHCH2 | 72.91 ± 0.01 | 135.29 ± 0.02 | 1.86 |

| 4ag | Br | CH2=CHCH2 | 168.03 ± 0.06 | 29.08 ± 0.03 | 0.17 |

| 4ba | H | HC≡CCH2 | 421.30 ± 0.03 | 896.70 ± 0.03 | 2.13 |

| 4bb | CH3 | HC≡CCH2 | 259.63 ± 0.01 | 455.59 ± 0.01 | 1.75 |

| 4bc | OCH3 | HC≡CCH2 | 412.69 ± 0.01 | 1206.84 ± 0.01 | 2.92 |

| 4bd | Cl | HC≡CCH2 | 392.91 ± 0.04 | 1327.55 ± 0.17 | 3.38 |

| 4be | CH2CH3 | HC≡CCH2 | 443.66 ± 0.01 | 1976.73 ± 0.09 | 4.46 |

| 4bf | F | HC≡CCH2 | 375.61 ± 0.03 | 894.37 ± 0.03 | 2.38 |

| 4bg | Br | HC≡CCH2 | 661.38 ± 0.09 | 894.77 ± 0.06 | 1.35 |

| Galantamine | – | – | 0.54 ± 0.7 | 8.80 ± 0.5 | 16.29 |

Values are the average from three independent experiments.

Selectivity for AChE is defined as IC50 (BChE)/IC50 (AChE).

The most effective inhibition among the evaluated molecules was shown by compound 4af against AChE (IC50 = 72 μ m) despite its poor selectivity (SI = 2). Alternatively, the best inhibitory activity on BChE was exhibited by compounds 4ab, 4ae, and 4ag (IC50 < 32 μ m). N‐allyl tetrahydroquinolines 4ae turned out to be the most active compound with IC50 = 25.58 μ m against BChE and with considerable selectivity (SI = 0.15). On the other hand, the evaluated N‐propargyl tetrahydroquinolines resulted in a poor inhibition of the AChE (IC50 = 259.63–661.38 μ m) compared to the reference drugs. However, they showed higher selectivity toward the AChE compared to the BChE (SI = 1.35–4.46).

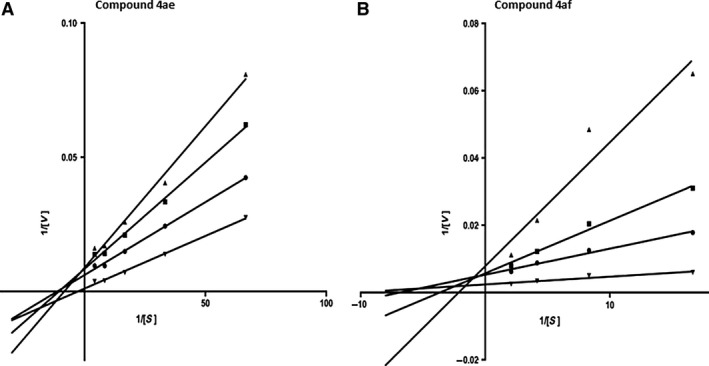

Enzymatic kinetic study

Cholinesterases are a group of serine hydrolases that catalyze the hydrolysis of acetylcholine, which leads to the termination of the nerve impulse transmission at the cholinergic synapses. Two types of cholinesterases are found in human (butyryl and acetyl), and the activity of AChE is many folds higher than that of BchE 42. The nature of cholinesterase inhibition, caused by the most active compounds (4ae and 4af) was determined by the graphical analysis of steady‐state inhibition data (Figure 1). Only three inhibitor concentrations (12.79, 25.58 and 51.16 μ m for 4ae and 36.46, 72.91 and 145.82 μ m for 4af) were used for Lineweaver‐burk plot graphs, because at higher concentrations the compounds lost their solubility. The study of Lineweaver‐burk reciprocal plots showed increasing slopes and very similar intercepts in the y‐axis with higher inhibitor concentrations. This suggests a possible reversible and competitive inhibition mechanism, where V max was constant, taking the same value while K m value increased for both compounds. This roughly means that these compounds compete with the substrate for binding at the same active site.

Figure 1.

Lineweaver‐Burk plots of (A) butyrylcholinesterase with substrate butyryltiocholine in absence and presence of inhibitor 4ae and (B) acetylcholinesterase with substrate acetylcholine in absence and presence of inhibitor 4af at three concentrations. (▼) No inhibitor; (■) IC 50; (●) down IC 50; (▲) up IC 50.

This competitive‐type inhibition, mechanism is also presented by galantamine, dibucaine, rivastigmine and others synthetic compounds like heteroarylacrilonitriles derivatives43, thiazolines and oxazolines44 and quinazolines45.

Computational studies

The alignment of sequence between AChE from Torpedo californica and Electrophorus electricus and BChE from Homo sapiens and serum bovine was carried out, obtaining an identity percentage of 65% and 90% respectively. It is consistent with the work done by Chothia and Lesk 46. The alignments were obtained by Clustal Omega program, and identity percentages were calculated by blast tool from NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information).

Several molecular docking simulations were performed between fourteen synthesized molecules and their protein targets, taking into account the chirality of the studied ligands. Therefore, the binding and affinity computational studies were completed using the R and S enantiomers for each molecule (28 in total).

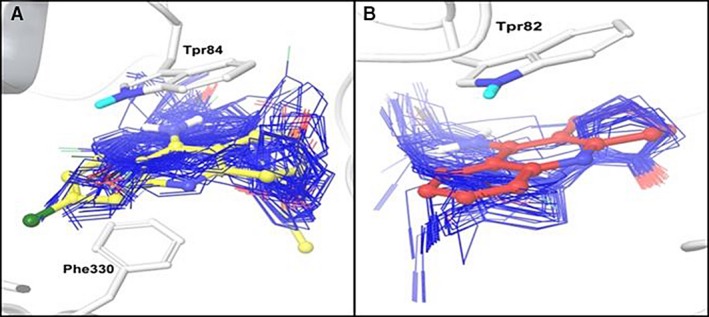

The top‐10 poses for each complex were selected from docking simulations, producing in total 280 poses that were analyzed for each target. To quickly and effectively process and organize the 560 poses, the python script cluster of ligands (available at www.schrodinger.com/scripcenter/) was used. In Figure 2 are shown the most populated clusters for each target. It can be seen that structures of docked compounds (blue) superimposed well and fit in the space occupied by reference ligands huprine (yellow) and tacrine (red). In general, our docking results showed that conformations adopted by docked compounds are similar to the X‐ray binding modes presented by huprine in AChE and tacrine in BChE.

Figure 2.

Predicted binding conformations of new ligands. The most populated clusters are showed in stick representation (blue). Reference ligands, huprine (yellow) and tacrine (red) are shown in ball & stick representation. The binding site residues are shown in stick representation (white). (A) acetylcholinesterase and (B) butyrylcholinesterase.

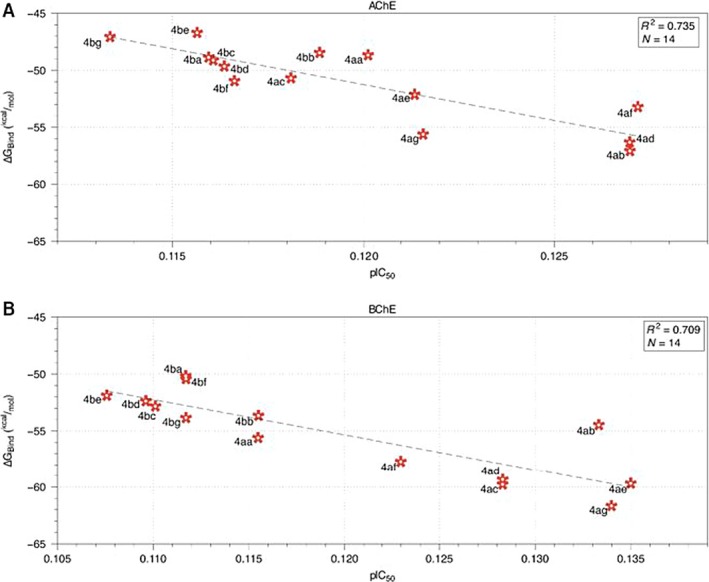

All poses for each complex were selected to estimate the ΔGbind. The calculated ΔGbind values, against pIC50, are plotted in Figure 3. The implemented computational protocol applied in the present study (molecular docking + MM‐GBSA) has been successful in predicting the binding affinity of new series of ligands against AChE and BChE targets. Moderate correlation coefficients (AChE: R 2 = 0.735 and BChE: R 2 = 0.709) were observed between the calculated ∆G bind and the experimental activity values.

Figure 3.

Correlation plots for predicted ∆G bind versus pIC 50 (A) acetylcholinesterase and (B) butyrylcholinesterase.

The plot of ΔG bind and experimental pIC50 reveals a moderate relationship between these two variables (Figure 3). The ∆G bind values for THQs ligands vary between −57.07 to −46.70 kcal/mol for AChE; and −61.66 to −50.16 kcal/mol for BChE.

This allowed us to understand the diversity of conformational poses and binding strength for the ligands interacting within the active site of their targets. Noteworthy, the most and less active compounds, against AChE and BChE, were correctly ranked by the applied computational protocol.

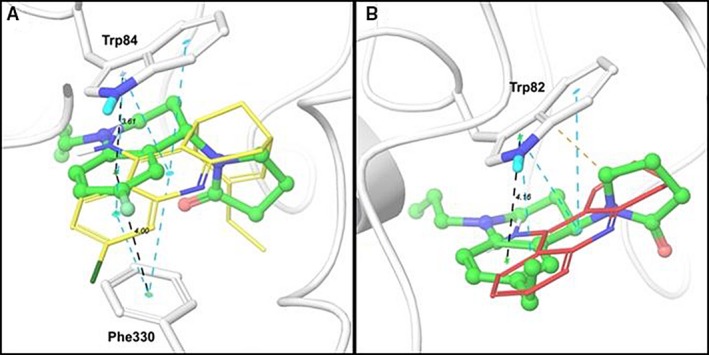

With the aim to study the interactions between the synthesized THQs inhibitors series, at an atomistic level, the molecular docking + MM‐GBSA protocol was applied. The best poses for the most potent AChE (molecule 4af) and BChE (molecule 4ae) inhibitors reported in this work were compared with the AChE 32 and BchE 33 ligands reported in previous crystal structures. In Figure 4A, shows the best conformational pose for molecule 4af (green) interacting with key AChE residues. This ligand establishes a π‐π‐stacking interaction with Trp84 (up) and Phe330 (bottom), which is the same interaction described by Dvir et al. 32, for huprine (Figure 4A, orange) in its crystal structure with AChE. The distances between the centroids for the π‐π stacking interaction system with compound 4af are shown in black dotted lines. These distances are 3.61 Å with respect toresidue Trp84 and 4.0 Å with respect to residue Phe330. Similarly, the π‐π stacking interaction system between the reference compound huprine and these two residues (Figure 4A, cyan dotted lines) present the same conformational interaction mode. This structural analysis allowed us to conclude that the most potent AChE inhibitor (4af) adopted a similar binding mode within the AChE active site, resembling the binding mode adopted by the reference ligand (huprine) in the PDB ID: 1E66.

Figure 4.

Binding molecular interactions for: (A) compound 4af (green) within the acetylcholinesterase (AChE) binding site and (B) compound 4ae (green) within the butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) binding site. The protein residues that establish interactions with the inhibitors are shown in white sticks and the reference ligands (huprine and tacrine) are shown in yellow and red lines representation respectively. AChE and BChE are shown in cartoon representation. Black dotted lines represent π‐π stacking interaction between 4af/4ae and AChE/BChE (distances are shown in Å). Cyan dotted lines represent π‐π stacking interaction between references ligands huprine/tacrine and AChE/BChE. Orange dotted line represents hydrophobic interaction between 4ae and BChE.

Similarly, as can be seen in Figure 4B, compound 4ae showed a π‐π stacking interaction against residue Trp82 within BChE active site. This interaction is the same reported for tacrine (Figure 4B, red) in the reference crystal with PDB ID: 4BDS 33. The inhibitor 4ae establishes a π‐π stacking interaction with residue Trp82 with a distance of 4.16 Å, while the same distance for tacrine is about 4.13 Å (not shown). Despite the small difference in the interaction distances, it can be said that the inhibitor 4ae acts like ligand reference tacrine.

The compounds 4af and 4ae interact with AChE and BChE, respectively, by hydrophobic interactions (mostly π‐π stacking). These compounds do not exhibit other kind of interactions (like H‐Bond interactions) and their binding modes are driven mainly by the π‐π stacking interaction system, which is in agreement with the same intermolecular interactions reported for reference ligands. These binding mode, in addition with the predicted ΔG bind and IC50 values allowed us to confirm that compounds 4af and 4ae are potential novel cholinesterase inhibitors.

Finally, one important characteristic that any biologically active compound should fulfill for being a candidate drug is the ability to cross biological membranes. Thereby, and in accordance with the above; a molecule must possess the appropriate ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) properties. In this work 44 significant physical descriptors and pharmaceutical properties of the compounds were analyzed; including among others: lipophilicity expressed as the octanol/water partition coefficient (log P), van der Waals surface areas of polar nitrogen and oxygen atoms (PSA) and other parameters related with Lipinski's rule. Therefore, theoretical prediction of the ADME properties for all compounds was described under different parameters showed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Main descriptors calculated for N‐allyl/propargyl tetrahydroquinolines using qikprop software

| Comp. | M.W. (g/mol) | Log P (o/w)a | Mol. Vol. (Å3)b | HB acceptorsc | HB donorsd | Rotatable bonds | PSAe | Log Sf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4aa | 256.35 | 2.676 | 918.63 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 30.894 | −2.84 |

| 4ab | 270.37 | 3.002 | 978.45 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 30.881 | −3.445 |

| 4ac | 286.37 | 2.687 | 984.54 | 4.75 | 0 | 3 | 39.094 | −2.784 |

| 4ad | 290.79 | 3.149 | 957.925 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 30.852 | −3.56 |

| 4ae | 284.4 | 3.381 | 1037.898 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 30.863 | −3.818 |

| 4af | 274.34 | 2.918 | 934.868 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 30.861 | −3.221 |

| 4ag | 335.24 | 3.248 | 968.817 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 30.812 | −3.707 |

| 4ba | 254.33 | 2.626 | 885.05 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 30.547 | −3.109 |

| 4bb | 268.36 | 2.934 | 944.33 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 30.57 | −3.723 |

| 4bc | 284.36 | 2.674 | 952.29 | 4.75 | 0.5 | 3 | 38.78 | −3.18 |

| 4bd | 288.78 | 3.118 | 928.76 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 30.541 | −3.91 |

| 4be | 282.39 | 3.279 | 997.85 | 4 | 0.5 | 3 | 30.542 | −3.973 |

| 4bf | 272.32 | 2.86 | 900.82 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 30.551 | −3.535 |

| 4bg | 333.23 | 3.195 | 937.68 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 30.536 | −4.025 |

QP log P for octanol/water (−2.0 to −6.5).

Total solvent accessible volume in cubic angstroms using a probe with a radius of 1.4 Å.

Estimated number of H‐bonds that would be accepted by solute from water molecules in an aqueous solution.

Estimated number of H‐bonds that would be donated by the solute to water molecules in an aqueous solution.

van der Waals surface areas of polar nitrogen and oxygen atoms.

Predicted aqueous solubility, log S, S in mol/dm3 (−6.5 to 0.5).

The analysis of the ADME results suggested that do not exist any important violations of Lipinski's rule because all calculated descriptors and properties are within the expected thresholds (Molecular weight (g/mol) = 254–335; Log P = 2.623–3.381; HB acceptors = 4–4.475 and HB donors = 0–0.5). Additionally, PSA and water solubility (log S) parameters, that are important in the membrane penetration and the absorption and distribution of drugs, respectively; were analyzed and the results were in the acceptable range defined for human use 47.

All physical and pharmaceutical properties calculated for the synthesized new molecules in this work are within the acceptable range defined for human use, thereby indicating their potential use as drug‐like molecules.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that synthetic N‐allyl/propargyl tetrahydroquinolines 4, obtained by an efficient, simple, and mild methodology based on the one‐pot cationic imino Diels–Alder reaction, present anticholinesterase effects. Furthermore, computational studies revealed the structure‐activity relationships of synthetized compounds, their binding conformational mode that, in addition with the ΔGbind predicted values, allowed us to confirm that the drug‐like compounds 4af and 4ae are novel cholinesterase modulators with potential therapeutic use.

Moreover, N‐allyl 1.2.3.4‐tetrahydroquinolines displayed better inhibitory activity against BChE in comparison with N‐propargyl 1.2.3.4‐tetrahydroquinoline and their Inhibitory activity was influenced by the substitution patterns of synthetic compounds. Selective inhibition of BChE over AChE may have another beneficial effect compared with the exclusive use of AChE inhibitors 48. In view that N‐allyl tetrahydroquinoline derivatives could be a new potent type of BChE inhibitors, further investigations will be held to optimize the biological activity profile of this type of molecular scaffold as future agents against Alzheimer's disease.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in the present work.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to COLCIENCIAS (grant no. RC‐0908‐2012) and CONICYT‐COLCIENCIAS 2012‐005 for giving financial support to this research work and for allowing the exchange of researchers between research participant countries. A.R.R.B. appreciates the financial support provided by the Universidad Industrial de Santander (VIE‐UIS. Project 1345). This Project was also supported by University of Talca (through PIEI‐Quim‐Bio Project), Y.R. thanks CONICYT‐Chile for a doctoral fellowship.

Notes

sigmaplot (2000) in version 10.0. Chicago, IL, USA: SPS Software Inc.

L. Schrödinger (2011) in Glide version 5.7; LigPrep version 2.5; Prime version 2.3. New York, NY, USA.

Contributor Information

Margarita Gutiérrez, Email: mgutierrez@utalca.cl.

Arnold R. Romero Bohórquez, Email: arafrom@uis.edu.co

References

- 1. Tsolaki M., Kokarida K., Iakovidou V., Stilopoulos E., Meimaris J., Kazis A. (2001) Extrapyramidal symptoms and signs in Alzheimer's disease: prevalence and correlation with the first symptom. Am J Alzheimers Dis;16:268–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wimo A., Jönsson L., Gustavsson A., McDaid D., Ersek K., Georges J., Gulacsi L., Karpati K., Kenigsberg P., Valtonen H. (2011) The economic impact of dementia in Europe in 2008—cost estimates from the Eurocode project. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry;26:825–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Perry E.K., Tomlinson B.E., Blessed G., Bergmann K., Gibson P.H., Perry R.H. (1978) Correlation of cholinergic abnormalities with senile plaques and mental test scores in senile dementia. BMJ;2:1457–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rizzo S., Bartolini M., Ceccarini L., Piazzi L., Gobbi S., Cavalli A., Recanatini M., Andrisano V., Rampa A. (2010) Targeting Alzheimer's disease: novel indanone hybrids bearing a pharmacophoric fragment of AP2238. Bioorg Med Chem;18:1749–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Inestrosa N.C., Alarcón R. (1998) Molecular interactions of acetylcholinesterase with senile plaques. J Physiol (Paris);92:341–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brus B., Kosak U., Turk S., Pišlar A., Coquelle N., Kos J., Stojan J., Colletier J.‐P., Gobec S. (2014) Discovery, biological evaluation, and crystal structure of a novel nanomolar selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibitor. J Med Chem;57:8167–8179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kelly C.A., Harvey R.J., Cayton H. (1997) Drug treatments for Alzheimer's disease. BMJ;314:693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gottwald M.D., Rozanski R.I. (1999) Rivastigmine, a brain‐region selective acetylcholinesterase inhibitor for treating Alzheimer's disease: review and current status. Expert Opin Investig Drugs;8:1673–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Scott L.J., Goa K.L. (2000) Galantamine. Drugs;60:1095–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Whitehouse P.J. (1993) Cholinergic therapy in dementia. Acta Neurol Scand;88:42–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davis K.L., Thal L.J., Gamzu E.R., Davis C.S., Woolson R.F., Gracon S.I., Drachman D.A., Schneider L.S., Whitehouse P.J., Hoover T.M. (1992) A double‐blind, placebo‐controlled multicenter study of tacrine for Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med;327:1253–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schulz V. (2003) Ginkgo extract or cholinesterase inhibitors in patients with dementia: what clinical trials and guidelines fail to consider. Phytomedicine;10:74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Melzer D. (1998) Personal paper: new drug treatment for Alzheimer's disease: lessons for healthcare policy. BMJ;316:762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sridharan V., Suryavanshi P.A., Menéndez J.C. (2011) Advances in the chemistry of tetrahydroquinolines. Chem Rev;111:7157–7259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kumar S., Bawa S., Gupta H. (2009) Biological activities of quinoline derivatives. Mini Rev Med Chem;9:1648–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pandit R.P., Lee Y.R. (2014) Efficient one‐pot synthesis of novel and diverse tetrahydroquinolines bearing pyranopyrazoles using organocatalyzed domino Knoevenagel/hetero Diels‐Alder reactions. Mol Divers;18:39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ding K., Flippen‐Anderson J., Deschamps J.R., Wang S. (2004) An efficient synthesis of optically pure (S)‐2‐functionalized 1, 2, 3, 4‐tetrahydroquinoline. Tetrahedron Lett;45:1027–1029. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Banks A., Breen G.F., Caine D., Carey J.S., Drake C., Forth M.A., Gladwin A., Guelfi S., Hayes J.F., Maragni P. (2009) Process development and scale up of a glycine antagonist. Org Process Res Dev;13:1130–1140. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kouznetsov V.V. (2009) Recent synthetic developments in a powerful imino Diels‐Alder reaction (Povarov reaction): application to the synthesis of N‐polyheterocycles and related alkaloids. Tetrahedron;65:2721–2750. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Behbahani F.K., Ziaei P. (2014) Synthesis of 1, 2, 3, 4‐tetrahydroquinolines using AlCl3 in aqua mediated. J Korean Chem Soc;58:144–148. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dehnhardt C.M., Espinal Y., Venkatesan A.M. (2008) Practical one‐pot procedure for the synthesis of 1, 2, 3, 4‐tetrahydroquinolines by the Imino‐Diels‐Alder reaction. Synth Commun;38:796–802. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beifuss U., Ledderhose S. (1995) Intermolecular polar [4π++ 2π] cycloadditions of cationic 2‐azabutadienes from thiomethylamines: a new and efficient method for the regio‐and diastereo‐selective synthesis of 1, 2, 3, 4‐tetrahydroquinolines. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun;20:2137–2138. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bolea I., Gella A., Unzeta M. (2013) Propargylamine‐derived multitarget‐directed ligands: fighting Alzheimer's disease with monoamine oxidase inhibitors. J Neural Transm (Vienna);120:893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim B.C., Lee S.H., Jang M., Won M.H., Park J.H. (2015) (S)‐Allyl cysteine derivatives as a new‐type cholinesterase inhibitor. Bull Korean Chem Soc;36:52–58. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Romero Bohorquez A., Escobar Rivero P., M Leal S., V Kouznetsov V. (2012) In vitro activity against Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania chagasi parasites of 2, 4‐diaryl 1, 2, 3, 4‐tetrahydroquinoline derivatives. Lett Drug Des Discov;9:802–808. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kouznetsov V.V., Gómez C.M.M., Derita M.G., Svetaz L., del Olmo E., Zacchino S.A. (2012) Synthesis and antifungal activity of diverse C‐2 pyridinyl and pyridinylvinyl substituted quinolines. Bioorg Med Chem;20:6506–6512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fonseca‐Berzal C., Arenas D.R.M., Bohórquez A.R.R., Escario J.A., Kouznetsov V.V., Gómez‐Barrio A. (2013) Selective activity of 2, 4‐diaryl‐1, 2, 3, 4‐tetrahydroquinolines on Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes and amastigotes expressing β‐galactosidase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett;23:4851–4856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Romero Bohórquez A.R., Kouznetsov V.V., Zacchino S.A. (2014) Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of antifungal properties of some 4‐aryl‐3‐methyl‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydroquinolines derivatives. Univ Sci (Bogota);20:13. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bohórquez A.R.R., Kouznetsov V.V. (2010) An efficient and short synthesis of 4‐Aryl‐3‐methyltetrahydroquinolines from N‐benzylanilines and propenylbenzenes through cationic imino Diels–Alder reactions. Synlett;2010:970–972. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ellman G.L., Courtney K.D., Andres V. Jr, Feather‐Stone R.M. (1961) A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol;7:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Teodoro M.L., Phillips G.N., Jr, Kavraki L.E., editors. Molecular docking: a problem with thousands of degrees of freedom. Robotics and Automation Proceedings 2001 ICRA IEEE International Conference on; 2001.

- 32. Dvir H., Wong D.M., Harel M., Barril X., Orozco M., Luque F.J., Muñoz‐Torrero D., Camps P., Rosenberry T.L., Silman I., Sussman J.L. (2002) 3D structure of torpedo californica acetylcholinesterase complexed with huprine X at 2.1 Å resolution: kinetic and molecular dynamic correlates. Biochemistry;41:2970–2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nachon F., Carletti E., Ronco C., Trovaslet M., Nicolet Y., Jean L., Renard P.‐Y. (2013) Crystal structures of human cholinesterases in complex with huprine W and tacrine: elements of specificity for anti‐Alzheimer's drugs targeting acetyl‐ and butyryl‐cholinesterase. Biochem J;453:393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jorgensen W.L., Maxwell D.S., Tirado‐Rives J. (1996) Development and testing of the OPLS all‐atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J Am Chem Soc;118:11225–11236. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eldridge M.D., Murray C.W., Auton T.R., Paolini G.V., Mee R.P. (1997) Empirical scoring functions: I. The development of a fast empirical scoring function to estimate the binding affinity of ligands in receptor complexes. J Compu Aided Mol Des;11:425–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hou T., Wang J., Li Y., Wang W. (2010) Assessing the performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 1. The accuracy of binding free energy calculations based on molecular dynamics simulations. J Chem Inf Model;51:69–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Adasme‐Carreño F., Muñoz‐Gutierrez C., Caballero J., Alzate‐Morales J.H. (2014) Performance of the MM/GBSA scoring using a binding site hydrogen bond network‐based frame selection: the protein kinase case. Phys Chem Chem Phys;16:14047–14058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li J., Abel R., Zhu K., Cao Y., Zhao S., Friesner R.A. (2011) The VSGB 2.0 model: a next generation energy model for high resolution protein structure modeling. Proteins;79:2794–2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Caporuscio F., Rastelli G., Imbriano C., Del Rio A. (2011) Structure‐based design of potent aromatase inhibitors by high‐throughput docking. J Med Chem;54:4006–4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lipinski C.A., Lombardo F., Dominy B.W., Feeney P.J. (2012) Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev;64:4–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gutiérrez M., Matus M.F., Poblete T., Amigo J., Vallejos G., Astudillo L. (2013) Isoxazoles: synthesis, evaluation and bioinformatic design as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. J Pharm Pharmacol;65:1796–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Darvesh S., Hopkins D.A., Geula C. (2003) Neurobiology of butyrylcholinesterase. Nat Rev Neurosci;4:131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. de la Torre P., Saavedra L.A., Caballero J., Quiroga J., Alzate‐Morales J.H., Cabrera M.G., Trilleras J. (2012) A novel class of selective acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: synthesis and evaluation of (E)‐2‐(Benzo [d] thiazol‐2‐yl)‐3‐heteroarylacrylonitriles. Molecules;17:12072–12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gawron O., Keil J. (1960) Competitive inhibition of acetylcholinesterase by several thiazolines and oxazolines. Arch Biochem Biophys;89:293–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Decker M., Krauth F., Lehmann J. (2006) Novel tricyclic quinazolinimines and related tetracyclic nitrogen bridgehead compounds as cholinesterase inhibitors with selectivity towards butyrylcholinesterase. Bioorg Med Chem;14:1966–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chothia C., Lesk A.M. (1986) The relation between the divergence of sequence and structure in proteins. EMBO J;5:823–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Singh K.D., Kirubakaran P., Nagarajan S., Sakkiah S., Muthusamy K., Velmurgan D., Jeyakanthan J. (2012) Homology modeling, molecular dynamics, e‐pharmacophore mapping and docking study of Chikungunya virus nsP2 protease. J Mol Model;18:39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cerbai F., Giovannini M.G., Melani C., Enz A., Pepeu G. (2007) N 1 phenethyl‐norcymserine, a selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibitor, increases acetylcholine release in rat cerebral cortex: a comparison with donepezil and rivastigmine. Eur J Pharmacol;572:142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]