Abstract

Thermal decomposition and kinetics behaviour of the de-oiled seed cake of African star apple (Chrosophyllum albidum) has been investigated using thermogravimetry under the nitrogen atmosphere from ambient temperature to 900 °C. The thermogravimetric data for the cake decomposition at six different heating rates (5, 10, 15, 20, 30 and 40 °C/min) were used to evaluate the kinetic decomposition of the cake using Friedman (FD), Kissinger-Akahira-Sunose (KAS) and Flynn-Wall-Ozawa (FWO) models. Thermal decomposition of the cake showed thermograms indicating dehydration and devolitilization stages (200–400 °C). The maximum temperature for the decomposition of the cake (Tmax) increases from 289.42–335.96 °C with increase in heating rates. The average apparent activation energy (Ea) values of 153.15, 145.14 and 147.15 kJ/mol were calculated using Friedman, Kissinger-Akahira-Sunose, and Flynn-Wall-Ozawa models respectively. The extent of mass conversion (α) shows dependence on apparent activation Ea values which is an evidence of multi-step decomposition kinetic. The thermal profile and kinetic data obtained could be helpful in evaluating the thermal stability of the cake as well as modeling, designing and developing a thermo-chemical system for the conversion of the cake to fuel.

Keywords: Physical chemistry, Analytical chemistry

1. Introduction

Globally, interest on quest for the sources of greener fuels is gaining tremendous increase especially to bridge the gap between the fuel supply and demand, as well as for safeguarding the environment from myriad of consequences associate with conventional fuels. Different approaches are currently being used for searching economical and viable alternative fuels from waste streams and other abundant natural resources. Biomass is one of these resources perceived by many researchers as veritable option for generation of greener fuels and other chemical compounds like methanol, hydrocarbons, aromatics, charcoal etc. (Yaman, 2004; Balat, 2008). Cellulose, hemicelluloses and lignin are the main components of biomass with traces of extractives such as terpenes, tannins, moisture, resin etc (Orfao et al., 1999). Biomass are converted to more valuable energy forms via a number of processes including thermal, biological, chemical, and mechanical processes (Bhaskar et al., 2011; Karagoz, 2009). Thermogravimetric analysis is of one the thermal techniques used for assessing characteristic biomass decomposition and its chemical kinetics. Biomass pyrolysis is considered as heterogeneous chemical reaction which is affected by the breakage and redistribution of chemical bonds, changing reaction geometry and interfacial diffusion of reactant and products (Galwey and Brown, 1988). The rate limiting step of heterogeneous reaction may be ascribed to nucleation, adsorption, interfacial reaction or surface/bulk diffusion, with regard to experimental conditions (White et al., 2011).

There are several kinetic methods for analyzing non-isothermal data obtained from TGA (Sbirrazzuoli et al., 2009; Khawam, 2007). These methods include model-fitting and iso-conversional (Model-free method). Model fitting methods involve data fitting into the different chosen model equations to give the best statistical fit from which the kinetic parameters are calculated. However, model-free method requires data for different heating rates and several kinetic curves for the calculation of activation energy. In the past, model-fitting methods were widely used for solid state reaction because of their ability to directly determine the kinetic parameters from a single TGA measurement. Yet, these methods suffer a setback for their inability to uniquely determine the reaction model especially for non-isothermal data (Khawam and Flanagan, 2005). Several models were statistically equivalent, whereas the fitted kinetic parameters may differ by an order of magnitude and therefore selection of an appropriate model become difficult. This method has paved way in favor of iso-conversional methods which is associated with simplicity and errors free with the choice of a kinetic model (Opfermann et al., 2002). These methods allow estimates of the activation energy, Ea, at specific extent of conversion, for an independent model. Repeating this procedure at different conversion values, give a profile of the activation energy as a function of α.

Although several pyrolysis kinetic models on solid biomass were reported (Damartzi et al., 2011; Slopiecka et al., 2012; Lopez-Velazquez et al., 2013; Ceylan and Topcu, 2014). The present study investigates the thermogravimetric studies on African star apple seeds cake which is rarely being documented. The physicochemical properties, kinetic parameters and kinetics modeling of the Chrosophyllum albidum seed de-oiled cake via non-isothermal thermogravimetry were reported.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample collection and characterization

Seeds of Chrosophyllum albidum were collected from vegetable market popularly known as “kasuwar daji” in Sokoto metropolis, Nigeria. The collected seeds were crushed to fine powder and de-oiled using soxhlet method. The proximate content of the solvent free de-oiled cake was determined in accordance with ASTM D3173 method. Fixed carbon content was determined using ASTM D-271-48 test method. Vario Micro Elemental Analyzer and Parr 6300 bomb Calorimeter were used for the determination of CHNS and gross calorific value respectively.

2.2. Thermogravimetric analysis

The pyrolysis experiment was performed using TGA analyzer, Shimadzu DTG-60 under nitrogen at 100 ml/min flow rate. The nitrogen provides the inert medium for the process. The seed cake of Chrosophyllum albidum sample with average particle size of 50 μm was used for the experiment at heating rates of 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, and 40 °C/min respectively; from ambient temperature to 900 °C.

2.3. Kinetics modeling

Biomass pyrolysis is a solid phase kinetic decomposition which its rate can be explained on the basis of Arrhenius equation expressed as:

| (1) |

Where A is the pre-exponential factor, Ea the activation energy, R the gas constant, T is absolute temperature in Kevin. The fundamental rate equation used in kinetic studies can be written as:

| (2) |

Where is the rate dependence on the model, is the rate of conversion at constant temperature.

One of the methods for measuring rate of sample decomposition in TGA is weight loss of the sample. The weight loss of sample is defined as:

| (3) |

Where Wi,Wt and Wf are initial mass of the sample, mass of the sample at a given time t and final mass of the sample at the end of reaction respectively. The extent of mass conversion is symbolized by α. Substitution of the rate constant (k) from Eq. (1) into Eq. (2), gives:

| (4) |

For a controlled temperature and constant heating rate constant. The rearrangement of Eq. (4) gives:

| (5) |

Integration of Eq. (5) resulted in:

| (6) |

Where g(α) is the integral form of the reaction model or conversion dependant f (α). The right side of the equation has no exact analytical solution. According to Yaman (2004), numerous approximations methods can be used for the solution of the right hand side of Eq. (6). This formed the basis upon which various integral model equations were derived.

2.4. Iso-conversion methods

Iso-conversional methods are model free methods which are frequently used in solid state kinetics for the prediction of apparent activation energies at progressive values of conversion (Raveendran et al., 1996; Ensoz and Can, 2002). Iso-conversion methods assume that the reaction model f(α) in the rate equation is independent of the heating rates rather on temperatures (Tα) at a particular conversion. These kinetic models include FD, KAS, Flynn–Wall–Ozawa, FWO etc.

2.4.1. Friedman method

Friedman (FD) is a differential form of iso-conversion model which is used for the determination of activation energy. The method is considered to be more accurate for the determination of apparent activation energy than the other iso-conversion methods as it does not include mathematical approximations. The model equation can be derived from Eq. (4) by multiplying both sides of equation with β:

| (7) |

Taking natural logarithm of each side of Eq. (7) gives

| (8) |

According White et al. (2011); the apparent activation energy (Ea) can be obtained from the slope for the plot of versus at a constant α value.

2.4.2. Kissinger-Akahira-Sunose (KAS)

The Kissinger-Akahira-Sunose (KAS) method is an integral iso-conversional method (Eq. (9)) used widely for the determination of apparent activation energy (Damartzi et al., 2011; Ceylan and Topcu, 2011): The Kissinger-Akahira-Sunose (KAS) method equation is expressed in Eq. (9)

| (9) |

Therefore, a plot of versus at constant conversion for different heating rates gives a straight line whose slope can be used for evaluation of the apparent activation energy and pre-exponential factor can be obtained from its intercept.

2.4.3. Flynn –Wall–Ozawa (FWO)

The FWO method (Eq. (10)) is often used to obtain the apparent activation energy (Ea) from the plot of logarithms of heating rates versus 1/T.

| (10) |

Thus, plot of log (β) versus 1/T; gives a slope of −0.457 Ea/R.

2.5. Coats-Redfern method

Coats-Redfern method is most often used to calculate the pre-exponential factor, the apparent reaction order, as well as to validate the estimated activation energy determined using iso-conversional methods (Jankovic and Smiciklas, 2012, Damartzi et al., 2011). The equations for the Coats-Redfern method are shown in Eqs. (11) and (12).

| (11) |

| (12) |

where n is the reaction order, β is the heating rate.

2.6. Thermodynamic parameters

Thermodynamic parameters were derived using equation reported by Kim et al. (2010). These include changes in enthalpy, entropy and Gibbs free energy which were calculated from the following relationship:

| (13) |

| (14) |

Where is maximum decomposition temperature from the DTG peak, kB represents the Boltzmann constant and h, the plank constant. Since,

| (15) |

| (16) |

The entropy change for the activated complex can be determined from thermodynamic expression given as:

| (17) |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Proximate and ultimate analyses

Proximate analysis gives first hand information on the properties of a feedstock which extensively provides an insight on how best a substrate could be handled and converted into useful energy carrier. These properties include the moisture, ash; fixed carbon and volatiles matter contents and calorific value. Table 1 shows results of proximate and ultimate analyses of the de-oil cake of African star apple. The cake has moisture content (10.93 ± 0.66 wt %) which is comparable to that of coal (11%) as reported by Mckendry, (2002) but higher than 6.91% and 2.763% reported for Lagenaria vulgaris and Cucurbita pepo seeds cake respectively (Sokoto et al., 2013). High moisture in feedstock (> 10 wt %) may result to production of low quality bio-oil upon pyrolysis (Bridgewater, 2012) as well as lowers the energy content of solid fuel. Also, high moisture content could results to ignition difficulty for solid fuels. The volatile matter in the de-oil seed cake of African star apple (Table 1) is high compared to the content in ground nut cake (83%) (Sachin et al., 2011) and rapeseed cake (81.5%) (Pstrowska et al., 2010). High volatile matter in biomass indicates rapid tendency to combustion, thus the Chrosophyllum albidum seed cake could enhance the combustion behaviour of coal when their blend is co-fired. Thus, the analyzed cake could be a good source of energy owing to it high volatile content (92.95%); as high volatility makes the biomasses attractive for combustion process (Demirbas et al., 2004).

Table 1.

Proximate and Ultimate Analyses of Chrosophyllum albidum seed Cake.

| Parameter | Values |

|---|---|

| Moisture (wt %) | 10.93 ± 0.66 |

| Ash (db%) | 2.35 ± 0.87 |

| Volatile matter (db %) | 92.95 ± 0.51 |

| Fixed carbon (db %) | 4.70 ± 0.14 |

| NCV (MJ/kg) | 13.02 |

| Element | |

| Carbon (%) | 39.82 ± 0.15 |

| Nitrogen (%) | 0.69 ± 0.45 |

| Hydrogen (%) | 6.94 ± 0.03 |

| Sulphur (%) | 1.84 ± 0.05 |

| Oxygen (%) | 48.36 ± 0.54 |

| O/C | 1.21 |

| H/C | 0.17 |

Values are mean of triplicate determination ± SD, db% = measurement on dry basis, oxygen was determine from the equation: % Oxygen = 100- %(C + H + N + S + Ash).

Ash content describes the burning behavior of solid fuel. High ash content is associated with excessive deposit that reduces heat transfer, heating efficiency, and fouling and agglomeration in combustion chamber (Mckendry, 2002). The ash content (2.35 ± 0.87) obtained in the present study is lower than the value reported for Lagenaria vulgaris and C. pepo. This implies that decomposition of the cake in boiler and furnace may have less deposit and slagging impact. Calorific value measures the quantity of heat to be emitted on combustion of fuel. The calorific value obtained from the cake is similar to some biomass feedstock (Table 2).

Table 2.

Calorific Value of Chrosophyllum albidum seed cake and other literature values.

| Biomass | Calorific Value (MJ/kg) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| African star Apple | 16.44 | Present study |

| Groundnut cake | 15 | (Kumar et al., 2011) |

| Mustard cake | 14.56 | (Sakar et al., 2013) |

| Pine wood | 18.3 | (Ryu et al., 2006) |

| Date seed | 18.97 | (Sait et al., 2012) |

Ultimate analysis of the cake showed relatively high percentage of sulphur and low nitrogen content. This infers that decomposition of the cake could generate gas which poses some negative effect to environment.

3.2. Trace metals content

Biomass is inherently composed of inorganic constituent that undergoes some chemical transformation leading to fouling and slagging effect. The alkali (i.e. Na, K, Mg, P and Ca) and alkaline metals content of biomass, in combination with other elements had been found to be responsible for these undesirable reactions (Jenkins et al., 1998). The reaction of alkali metals with silica present in the ash produces a sticky, mobile liquid phase, which can lead to blockages of airways in the furnace and boiler plant (Mckendry, 2002). Although the presence of these metals in biomass might be inevitable, their effect is minimal when the concentration is low. Presence of alkali and alkaline earth metal in less than 2% concentration has mild effect on fouling and slagging (Lara et al., 2015). The concentrations of alkali and alkaline earth metal detected in Chrosophyllum albidum seed cake (Table 3) were lower than 2%. However, transition metal concentrations were less than 1 ppm which infers insignificant effect of heavy metal emission upon combustion.

Table 3.

Trace Element Composition of Chrosophyllum Albidum Seed Cake.

| Element | Concentration (mg/kg) |

|---|---|

| Mg | 495 ± 1.05 |

| Ca | 1184 ± 2.12 |

| Ni | < 1 |

| Mn | 11 ± 0.15 |

| V | < 1 |

| Fe | 26 ± 0.25 |

| Zn | 15 ± 0.02 |

| Al | 10 ± 0.05 |

| Cr | < 1 |

| P | 733 ± 0.05 |

| Na | 199 ± 1.10 |

| K | 7178 ± 2.15 |

| Pb | < 1 |

| Co | < 1 |

3.3. Thermal characterization

The TG curves for the decomposition of the Chrosophyllum albidum seed cake show a single major peak at temperature above 250 °C. Although a minor peak signifying removal of adsorb water was noticeably between a temperature range of 25–100 °C. The thermal decomposition of the cake occurred within the temperature range of 200–400 °C, with maximum decomposition of 87.66%. The degradation temperature is comparable to that reported for cellulose (Sanchez-Silva et al., 2012; Vamvuka et al., 2003). The pyrolysis temperature observed in the present study is comparable to the degradation temperature range 200–500 °C for grape baggase (Onay, 2007) and cherry seeds (Duman et al., 2011). However, the decomposition temperature for Chrosophyllum albidum seed cake is lower than 400–700 °C and 400–800 °C for groundnut (Kumar et al., 2011) and rapeseeds cakes (Koçkar and Onay, 2004). The curves imply that complete pyrolysis of the Chrosophyllum albidum seed cake can be achieved at about 350 °C. The maximum degradation temperature implies that cellulose is likely to be the major component of the Chrosophyllum albidum seed cake.

3.4. Effect of heating rate

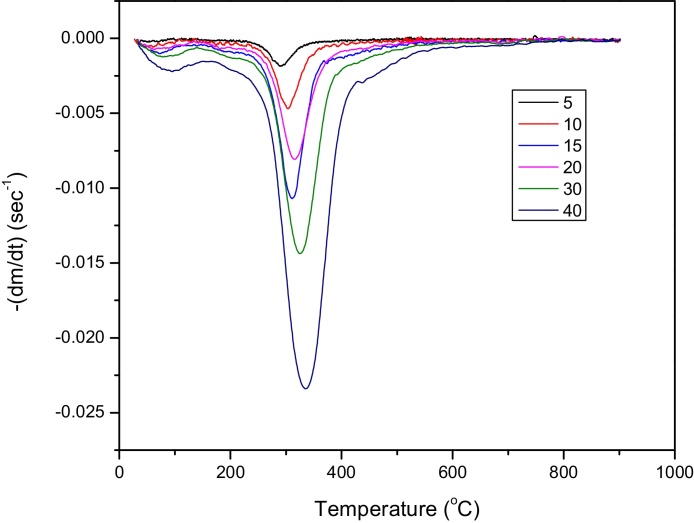

The DTG profiles shown in Fig. 1 indicate that heating rate influenced the temperatures ranges of the pyrolysis process. The curve reveled that increase in heating rate shifted the pyrolysis temperature to higher value. It was also observed that maximum weight loss decrease with increases in the heating rates. This is in conformity with findings reported by Sanchez-Silva et al. (2012); Li et al. (2010). However, pyrolysis studies of rapeseed shows reduction in decomposition with the change in heating rate from 20 to 50 °C min−1. The shift in temperature values could be due to poor heat conductivity of the biomass that impedes heat transfer within the biomass particles, hence result to temperature gradient. As the heating rate increases temperature gradient within the sample particle increase thereby elevating the temperature at which pyrolysis progress (Zhang et al., 2004). Also increase in heating rate from 5 to 40 °C per min shift the Tmax to high value (Table 4) with corresponding temperature shift from 289.42 to 335.96 °C which could be attributed to an increased thermal lag.

Fig. 1.

DTG graph of Chrosophyllum albidum seed cake at different heating rates.

Table 4.

Characteristic Devolatization Temperature and to volatile matter for ASA at Different Heating Rates.

| Heating rate (°C/min) | On set temp (°C) | End set temp (°C) | T max (°C) | Percentage decop (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 255.78 | 313.55 | 289.42 | 88.95 |

| 10 | 261.85 | 342.94 | 303.86 | 87.15 |

| 15 | 263.85 | 351.90 | 311.08 | 83.87 |

| 20 | 266.05 | 356.48 | 315.02 | 87.32 |

| 30 | 278.31 | 382.58 | 325.86 | 85.23 |

| 40 | 276.20 | 298.02 | 335.96 | 84.12 |

The shifts in Tmax observed (Fig. 1) with increases in heating rate, suggests that the reaction rate is only function of the temperature and that the pyrolytic cracking mechanism of the reaction is independent of the heating rates, under the used experimental conditions.

3.5. kinetics parameters

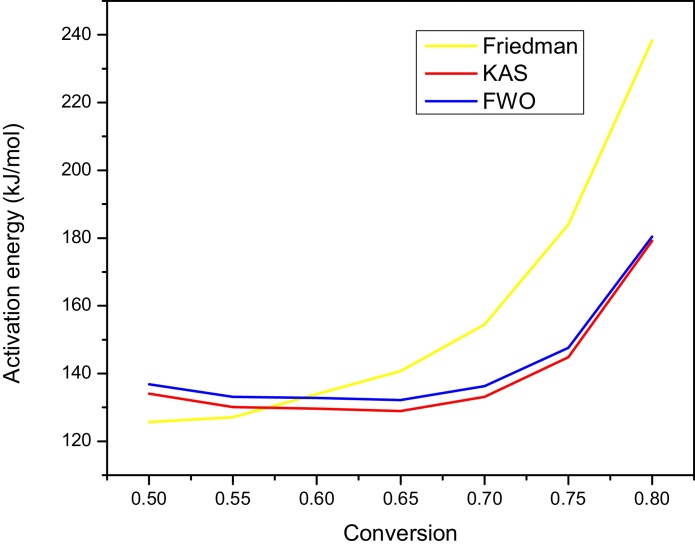

The kinetic parameters determined using different model equations mentioned above is presented in Table 5. The activation energy signifies the ease at which the degradation process occurred. The activation energy values shown in (Table 5) were obtained using Friedman, KAS and FWO model equations respectively. Values in the 0.05 ≤ α ≤ 0.8 range, corresponding to the temperatures between 195 and 345 °C, because the results for α < 0.05 and α > 0.8 are not accurate enough judging for very low correlation coefficient, hence their inclusion might cause an error. For the Friedman methods, the activation energy values were calculated using Eq. (8). The apparent activation energy values at different conversion were different which signifies that the decomposition process proceed via multi-step reaction (Slopiecka et al., 2011). The activation energy values, however decreases with increasing conversion from 0.1–0.5. The activation energy values calculated using KAS and FWO methods decreases with an increasing conversion from 2 to 65 % conversions. The apparent Ea values obtained from these methods vary at designated conversions indicating that reaction mechanism is not the same in the whole decomposition process and the activation energy is dependent on conversion (Slopiecka et al., 2011). It can also be observed from Table 5, that the average activation energies values were 153.15 kJ/mol, 145.14 kJ/mole and 147.15 kJ/mole for the FD, KAS and FWO methods respectively. This implies that Ea values calculated using FD method were higher than values obtained from KAS and FWO. Whereas average Ea values for KAS and FWO were similar and could probably describe the tendency of the models to predict the apparent activation energy values of the degradation process.

Table 5.

Apparent Activation Energy (kJ/Mol) at different conversion derived from Friedman, KAS and FWO models with their correlation coefficient values (R2).

| FRIEDMAN |

KAS |

FWO |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | Ea | R2 | Ea | R2 | Ea | R2 |

| 0.05 | 135.7153 | 0.96733 | 136.4549 | 0.95585 | 137.3893 | 0.96039 |

| 0.10 | 168.7535 | 0.99702 | 147.0112 | 0.99141 | 148.0706 | 0.99234 |

| 0.15 | 170.5549 | 0.99816 | 155.4288 | 0.99797 | 156.3909 | 0.99818 |

| 0.20 | 171.9023 | 0.99911 | 161.3871 | 0.99828 | 162.2337 | 0.99845 |

| 0.25 | 157.0655 | 0.99883 | 158.6681 | 0.99899 | 159.7764 | 0.99911 |

| 0.30 | 144.7029 | 0.99799 | 153.4334 | 0.99878 | 154.8982 | 0.99893 |

| 0.35 | 138.7834 | 0.99426 | 148.4411 | 0.99816 | 150.2409 | 0.9984 |

| 0.40 | 130.3716 | 0.99125 | 142.4061 | 0.99668 | 144.5858 | 0.99713 |

| 0.45 | 128.3205 | 0.98674 | 139.1239 | 0.99558 | 141.5423 | 0.99619 |

| 0.50 | 125.6933 | 0.98402 | 134.0796 | 0.99377 | 136.8248 | 0.99466 |

| 0.55 | 127.0987 | 0.98286 | 130.0829 | 0.99125 | 133.1089 | 0.99253 |

| 0.60 | 133.9193 | 0.98364 | 129.6475 | 0.98963 | 132.7804 | 0.99115 |

| 0.65 | 140.6873 | 0.98512 | 128.9297 | 0.98836 | 132.1963 | 0.99009 |

| 0.70 | 154.4506 | 0.98709 | 133.1319 | 0.98477 | 136.3106 | 0.98695 |

| 0.75 | 183.9658 | 0.97916 | 144.8161 | 0.97868 | 147.5799 | 0.98147 |

| 0.80 | 238.3643 | 0.93137 | 179.1449 | 0.96248 | 180.4678 | 0.96642 |

| Average | 153.15 | 145.14 | 147.15 | |||

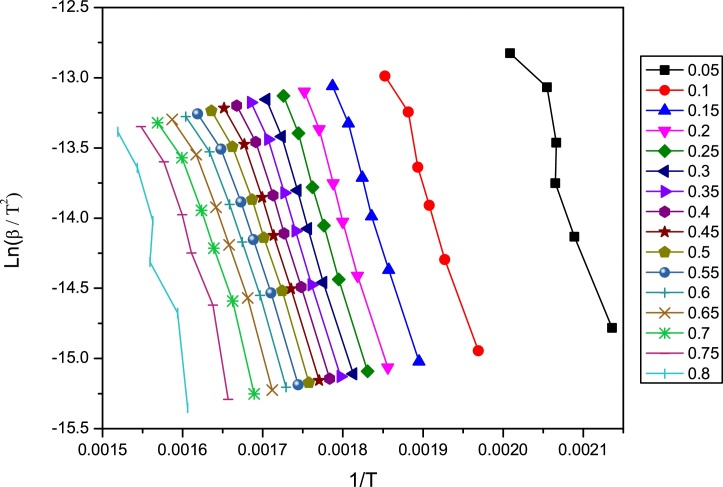

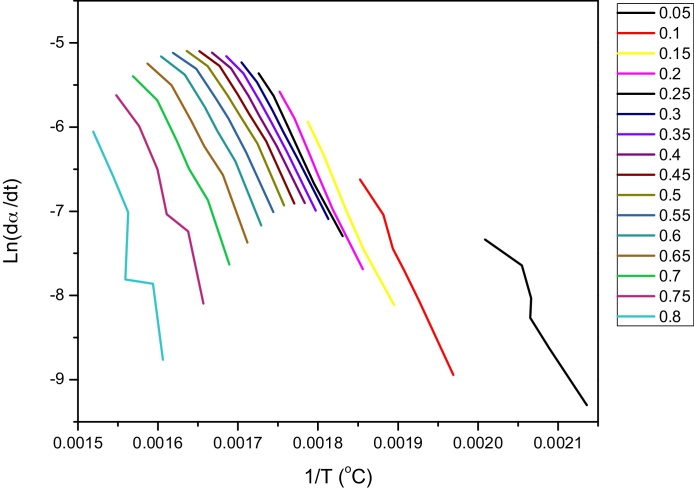

It is obvious from Fig. 2 that, the values for apparent activation energy calculated using the KAS and FWO methods were similar throughout the degradation process. The values obtained using FD method had higher values for activation energy from 60–80 % conversion. Lower values of activation infer that the degradation may occur at faster rate. It is evident from Fig. 2 that an increase of Ea values from conversion 0.7 till end of the reaction was observed. This could be attributed to the degradation of lignin; although the decomposition of the polymeric structure in the lignin starts at relatively low temperatures, about of 150–200 °C. The main process occurs around 400 °C, with the formation of complex compounds essentially aromatic hydrocarbons and phenolic and their derivatives (Alén et al., 1996; Rodriguez et al., 2001). Formation of these compounds probably might lead to competitive reactions, comprising of multiple and simultaneous processes which could have an influence to the rise in activation energy values. Fig. 3 shows the Linearization graph for the plot of Ln(β/T2) VS inverse of temperature for KAS model. While Linearization graph of the plot between ln(dα/dt) and inverse of temperature obtained from FD model is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of Activation energy values for FD, KAS and FWO model.

Fig. 3.

KAS model Linearization graph for the plot Ln(β/T2) VS inverse of temperature.

Fig. 4.

Linearization graph of the plot between ln(dα/dt) and inverse of temperature obtained from FD model.

The activation energy represents essentially the difficulty to start a reaction, while the frequency factor A indicates the occurred effective collision of reactant molecules. Lower Ea values denotes a reaction that is easier to start and occur, while less collision of reactant molecules infers lower values of pre-exponential factor.

The ΔH values reported in Table 6 were calculated using Eq. (15); the values are positive which indicate endothermic reactions. ΔH values influences the average product concentrations and pyrolysis time (Babu and Chaurasia, 2004). High values of ΔH infer the high degree of endothermicity. An increase in average concentration of char might be expect with increase in degree of endothermicity at the expense of volatile gases during pyrolysis. However, the final conversion time for pyrolysis increases with an increase in the ΔH value (Babu and Chaurasia, 2004). Thus, high degree of endothermicity could affect the activity of primary reaction in pyrolysis. The ΔS value obtained at lower heating rate for the degradation is negative, which indicates that formation of activated complex is accompanied by decrease in entropy, this implies that activated complex has a more ordered structure than the reactants and that the reactions are slower than normal (Markovska et al., 2010; Aravindakshan and Muraleedharan, 1990). The ΔS values obtained at heating rates of 10–40 °C/min were positive.

Table 6.

Kinetic parameters of African star apple seeds cake.

| Heating rate (s−1) | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 30 | 40 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A(s−1) | 1.4E + 13 | 7.26E + 13 | 1.85E + 14 | 1.36E + 14 | 1.11E + 14 | 2.07E + 14 |

| ΔH (kJ/Mol) | 161.558 | 170.1557 | 174.8576 | 173.2205 | 173.4216 | 178.2085 |

| ΔG (kJ/Mol) | 165.2916 | 166.3257 | 166.4882 | 166346.7 | 167.5056 | 169.1456 |

| ΔS(JK−1) | -6.81448 | 6.637546 | 14.32544 | 11.68685 | 9.884578 | 14.879 |

| Order (n) | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.1 |

3.6. Mass balance of bio-oil produce from the African star apple seeds cake

Slow pyrolysis process of the samples at temperature range of 300–450 °C with heating rate of 10 °C min−1 resulted to gaseous, liquid and solids products. The mass balance for these products is shown in Table 7. The maximum liquid yield of 48.3% was obtained at 400 °C and the extent of conversion of 72%. The produced liquids were found to comprise of several chemical compounds in which phenols and their derivatives being the major compounds. These compounds could be catalytically upgraded to hydrocarbon and to produce a range of chemicals commodity. The solid char obtained from pyrolized samples are environment friendly and find application as catalysis support, activated carbon, in making nano-catalyst and as fuel in boiler

Table 7.

Mass of Balance of the Feed conversion at Different Temperature (°C).

| Temp (°C) | Bio char (%) | Bio-oil (%) | Gas (%) | Aqueous (%) | Organic (%) | Conversion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | 38 | 43.7 | 18.3 | 88.33 | 11.67 | 62 |

| 350 | 34 | 45 | 21 | 82.88 | 17.11 | 66 |

| 400 | 28 | 48.3 | 23.7 | 78.47 | 21.53 | 72 |

| 450 | 28.0 | 45.6 | 26.4 | 82.46 | 17.54 | 72 |

4. Conclusion

This study presented an experimental kinetic study of Chrosophyllum albidum seed cake using thermogravimetric technique for the description of thermal degradation pattern of the cake in inert atmosphere. The main processes that occurred during the degradation of cake sample are dehydration process, between room temperature and 200 °C. Active pyrolysis stage that involve degradation of the cellulose and hemicelluloses occurred between 200 and 400 °C, the process occurred through consecutive stages of pyrolytic breaking on well-defined sites and competitive reactions as portrayed by different changes of Ea values. The final stage of the degradation process was associated with rise in activation energy and is presumed to indicate degradation of lignin. The rise in Ea values is likely due functional groups that energetically stable with polymeric matrix.

The results obtained according to the iso-conversion kinetics used in this study shows the dependence of Ea values on conversion which infers degradation proceed through complex reaction mechanism. The activation energy values of 153.15, 145.14 and 147.15 kJ/Mol were determined using Friedman, KAS and FWO models respectively. The reaction order was determined using Coats-Redfern equation.

The proximate and ultimate analyses of the cake showed that the cake has high volatile matter and lower ash content. Trace metal content of the Chrosophyllum albidum seed cake has low concentration (almost <1 mg/kg) of heavy metals and less than 2% of alkali and alkaline earth metals. The findings of this study infers the seeds cake of African star apple is a potential feedstock for fuel generation and the kinetic data would be of immense benefit to model, design and develop thermo-chemical system in Nigeria for the usage of this biomass material.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Abdullahi Muhammad Sokoto: Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Rawel Singh, Bhavya B. Krishna: Performed the experiments.

Jitendra Kumar: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Thallada Bhaskar: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding statement

This work was supported by NAM S&T India in conjunction with CSIR-Indian Institute of Petroleum, Bio-fuels Division, Dehradun.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Alén R., Kuoppala E., Oesch P. Formation of the main degradation compound groups from wood and its components during pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 1996;36:137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Aravindakshan K.K., Muraleedharan K. Kinetics of non-isothermal decomposition of polymeric complexes of n, n bis(dithiocarboxy) piperazine with iron(III) and cobalt(III) Thermochem. Acta. 1990;1(59):101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Babu B.V., Chaurasia A.S. Parametric study of thermal and thermodynamic properties on pyrolysis of biomass in thermally thick regime. Energy Convers. Manage. 2004;45:53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Balat M. Mechanisms of thermochemical biomass conversion processes. Part 1: reactions of pyrolysis. Energy Sources A Recovery Util. Environ. Effects. 2008;30(7):620–635. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar, T., Bhavya, B., Singh, R., Naik, D. V., Kumar, A., Goyaln, H.B. (2011). Biofuels Chapter 3—Thermochemical Conversion of Biomass to Biofuels: Alternative Feedstocks and Conversion Processes 2, Pages 51–77.

- Bridgewater A.V. Review of fast pyrolysis of biomass and product up gradation. Biomass Energy. 2012;38:68–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ceylan S., Topcu Y. Pyrolysis kinetics of hazelnut husk using thermogravimetric analysis. J. Bioresour. Technol. 2014;156(182):188. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damartzi T., Vamvuka D., Sfakiotakis S., Zabaniotou A. Thermal degradation studies and kinetic modeling of cardoon (Cynara cardunculus). Pyrolysis using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) Bioresour. Technol. 2011;102:6230–6238. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirbas A.H., Demirbas A.S., Demirbas A. Liquid fuels from agricultural residues via conventional pyrolysis. Energy Sources. 2004;26:821–827. [Google Scholar]

- Duman G., Okutucu C., Stahl R., Ucar S., Yanik J. The slow and fast pyrolysis of cherry seed. Bioresour. Technol. 2011;102:1869–1878. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensoz S.S., Can M. Pyrolysis of pine (Pinus Brutia Ten.) chips.: 1. Effect of pyrolysis temperatures and heating rate on the product yields. Energy Sources A Recovery Util. Environ. Effects. 2002;24:347–355. [Google Scholar]

- Galwey A.K., Brown M.E. Kinetic background to thermal Analysis and Calorimetry. In: Brown M.E., editor. Handbook of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, Vol. 1: Principles and Practice. 1st ed. Elsevier Science; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 1988. pp. 147–224. [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic B., Smiciklas I. The non-isothermal combustion process of hydrogen peroxide treated with animal bones: kinetic analysis. Thermochem. Acta. 2012;521(1–2):130–138. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins B.M., Baxter L.L., Miles T.R., Jr., Miles T.R. Combustion properties of biomass. Fuel Process. Technol. 1998;4:17–46. [Google Scholar]

- Karagoz S. Energy production from the pyrolysis of waste biomasses. Int. J. Energy Resour. 2009;33(6):576–581. [Google Scholar]

- Khawam A. PhD Thesis. Iowa University; Iowa: 2007. Application of solid state-kinetics to desolvation reactions. [Google Scholar]

- Khawam A., Flanagan D.R. Complementary use of model-free and modelistic methods in the analysis of solid-state kinetics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:10073–10080. doi: 10.1021/jp050589u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.S., Kim Y.S., Kim S.H. Investigation of thermodynamic parameters in thermal decomposition of plastic waste-waste lube oil compound. J. Environ. Sci. 2010;44:5313–5317. doi: 10.1021/es101163e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koçkar O.M., Onay O. Fixed-bed pyrolysis of rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) Biomass Bioenerg. 2004;26:289–299. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Agrawala A., Singh R.K. Thermogravimetric analyses of ground nut cake. Int. J. Chem. Eng. Appl. 2011;2(4):268–271. [Google Scholar]

- Lara F., Enrique G., David P., Pablo E., Araceli R. A comparative study of fouling and bottom ash from woody biomass combustion in a fixed-bed small-scale boiler and evaluation of the analytical techniques used. Sustainability. 2015;7:5819–5837. [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Chen L., Yi X., Zhang X., Ye N. Pyrolytic characteristics and kinetics of two brown algae and sodium alginate. Bioresour. Technol. 2010;101:7131–7136. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.03.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Velazquez M.A., Santes V., Balmaseda J., Torres-Garcia E. Pyrolysis of orange waste: a thermo-kinetic study. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 2013;99:170–177. [Google Scholar]

- Markovska I.G., Bogdanov B., Nedelchev N.M., Gurova K.M., Zagorcheva M.H., Lyubcheva L.A. Study on the thermochemical and kinetic characteristics of alkali treated rice husk. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2010;57:411–416. [Google Scholar]

- Mckendry P. Energy production from biomass (part I): overview of biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2002;83:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8524(01)00118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onay O. Influence of pyrolysis temperature and heating rate on the production of bio-oil and char from safflower seed by pyrolysis, using a well-swept fixed-bed reactor. Fuel Process. Technol. 2007;88:523–531. [Google Scholar]

- Orfao J.M., Antunes F.J.A., Figueiredo J.L. Pyrolysis kinetics of lignocellulosic materials- three independent reactions model. Fuel. 1999;78:349–358. [Google Scholar]

- Opfermann J.R., Kaisersberger E., Flammersheim H.J. Model-free analysis of thermoanalytical data-advantages and limitations. Thermochim. Acta. 2016;391:119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Pstrowska K., Walendziewski J., Stolarski M. Rapeseed oil cake pyrolysis-influence of temperature process on yeild and products properties. Proceedings of Third International Symposium on Energy from Biomass and Waste; Venice, Italy; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Raveendran K., Ganesh A., Khilar K.C. Pyrolysis characteristics of biomass and biomass components. Fuel. 1996;75:987–998. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J., Graca J., Pereira H. Influence of tree eccentric growth on syringyl/guaiacyl ratio in Eucalyptus globulus wood lignin assessed by analytical pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 2001;481:58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu C., Yang Y.B., Khor A., Yates N.E., Sharifi V.N., Swithenbank J. Effect of fuel properties on biomass combustion: part I. Experiments-fuel type, equivalence ratio and particle size. Fuel. 2006;85(7–8):1039–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Sachin K., Agrawalla Ankit, Singh K. Int. J. Chem. Eng. Appl. 2011;2(4):268–271. [Google Scholar]

- Sait H.H., Hussain A., Salema A.A., Ani F.N. Pyrolysis and combustion kinetics of date palm biomass using thermogravimetric analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;118:382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.04.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakar A., Dutta S., Chowdbury R. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2013;4(8):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Silva L., López-González D., Villaseñor, Sánchez J.P., Valverde J.L. Thermogravimetric–mass spectrometric analysis of lignocellulosic and marine biomass pyrolysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;109:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbirrazzuoli N., Vincent L., Mija A., Guio N. Integral, differential and advanced isoconversional methods: complex mechanisms and isothermal predicted conversion-time curves. Chemometr. Intell. Lab. 2009;96:219–226. [Google Scholar]

- Slopiecka K., Bartocci P., Fantozzi F. Thermogravimetric analysis and kinetics study of poplar wood pyrolysis. Third International Conference on Applied Energy; Perugia, Italy; 2011. pp. 1687–1698. [Google Scholar]

- Slopiecka K., Bartocci P., Fantozzi F. Thermogravimetric analysis and kinetic study of poplar wood pyrolysis. J. Appl. Energy. 2012;97:491–497. [Google Scholar]

- Sokoto M.A., Hassan L.G., Salleh M.A., Dangoggo S.M., Ahmad H.G. Thermo-chemical properties of Lagenaria vulgaris: Lagenaria ladle and Cucurbita pepo de-oiled cakes. Int. J. Pure Appl. Sci. Technol. 2013;18(1):12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Vamvuka D., Kakaras E., Kastanaki E., Grammelis P. Pyrolysis characteristics of biomass residuals mixture with lignite. Fuel. 2003;82:1949–1960. [Google Scholar]

- White J.E., Catallo W.J., Legendre B.L. Biomass pyrolysis kinetics: a comparative critical review with relevant agricultural residue case studies. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 2011;91:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Yaman S. Pyrolysis of biomass to produce fuels and chemical feedstocks. Energy Convers. Manage. 2004;45:651–671. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Xu M., Sun L. Study on biomass pyrolysis kinetics. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power Trans. ASME. 2004;128:493–496. [Google Scholar]