Abstract

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a chronic digestive disorder, which is characterized by abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea and constipation periods. The etiology is unknown. Based on the different mechanisms in the etiology, treatment focuses on controlling symptoms. Due to the longtime of syndrome, inadequacy of current treatments, financial burden for patients and pharmacologic effects, several patients have turned to the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Complementary and alternative treatments for IBS include hypnosis, acupuncture, cognitive behavior therapy, yoga, and herbal medicine. Herbal medicines can have therapeutic effects and adverse events in IBS. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of herbal medicines in the control of IBS, and their possible mechanisms of action were reviewed. Herbal medicines are an important part of the health care system in many developing countries It is important for physicians to understand some of the more common forms of CAM, because some herbs have side effects and some have interactions with conventional drugs. However herbal medicines may have therapeutic effects in IBS, and further clinical research is needed to assess its effectiveness and safety.

Keywords: Herbal medicine, Irritable Bowel Syndromes, Complementary Medicine

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The prevalence of IBS in children and adolescents is high. Various studies have reported prevalence to be approximately 8 to 12% in children, and 5 to 17% in adolescents. With this syndrome, abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea or bloating is known to occur. (1–3). The etiology of IBS is not fully understood. But evidence suggests roles for genetic, psychosocial factors, imbalance gut microbiota, increased intestinal permeability, immune activation, and central nervous system dysfunction (4). The main strategies of management of IBS are education, modified nutrition, dietary changes, pharmacotherapy, and a bio psychosocial approach (2).

1.2. Statement of problem

IBS is common, but no safe and effective conventional treatment exists. Consequently, the use of herbal medicine is an interesting option in patients. Many patients use (CAM), especially when facing a chronic illness for which treatment options are limited (5). The term complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) can be defined as “a group of diverse medical and healthcare systems, practices, or products that are not generally considered part of conventional medicine” (5). Herbal medicine is a kind of therapy that utilizes medicinal plants, to prevent or cure clinical conditions (6). Herbal medicine is a frequently used as an alternative treatment modality in the world. Herbal medicine is the most common CAM used on patients with IBS. An increasing number of IBS patients are beginning to receive complementary and alternative medicines in the world, The most frequently used are herbal remedies (43%).

1.3. Objective of research

The aim of this study was to systematically medicines and their possible mechanisms of action in controlling IBS.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Searched databases

Electronic databases including PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane library and Iranian databases SID and Magiran, were searched to access the efficacy of herbal medicines and IBS. The review was limited to studies published between 1995 and 2015. Titles, abstracts, and full texts for compliance with eligibility criteria, were reviewed.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Text articles in Persian, English language, literature reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analysis in IBS is inclusion criteria. The titles and abstracts of the article were evaluated. Articles with invalid reference and the lack of accurate methodology were exclusion criteria.

2.3. Quality assessment

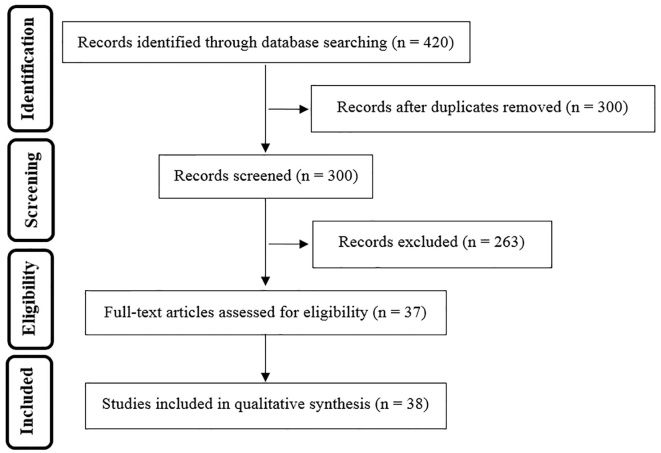

Analysis and quality evaluation of the literature were performed independently by two authors. The methodological quality evaluation of randomized clinical trial was carried out using the Cochrane Collaboration tool (7). Out of 420 records found in the mentioned databases, 37 related studies were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). This review has focused on the most important ancient herbal treatment: Aloe vera, Artichoke, Fumaria officinalis, Curcuma longa, Hypericum perforatum, Mentha piperita, Plantago psyllium and Melissa officinalis.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the selection process and exclusion criteria

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Aloe Vera

Aloe leaves contain a transparent gel which is most commonly used as a curative effect (8). Aloe is commonly used in IBS, especially the constipation-predominant subtype (9). A randomized, double-blind, cross-over placebo controlled study evaluated aloe vera in IBS. Statistical analysis of 47 patients showed no difference between the placebo and aloe vera treatment in quality of life in IBS (10) (Table 1). In a previous studyby Odes et al., 35 men and women were randomized to receive capsules containing celandine-aloe vera-psyllium, or placebo, for 28 days. They reported that abdominal pain was not reduced in either group, but preparation of herbal medicine was effective as a laxative in the treatment of constipation (11). In another study by Davis et al., aloe vera had no beneficial effect in IBS symptoms (12). In an Iranian clinical study by Khedmat et al., 33 patients with constipation-predominated refractory IBS into 8 weeks, they received aloe vera (30 ml twice daily). Pain/discomfort (p < 0.001) and flatulence decreased (p < 0.001), Stool consistence, urgency, and frequency of defecation did not change significantly (p > 0.5 in all) (13). In conclusion, Aloe vera can be beneficial in controlling IBS symptoms. Further placebo-controlled studies with larger patient population are needed.

Table 1.

Herbs used for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome

| Herbal medicine | Part | Type of study | Model | Results | Ref. no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aloe Vera | Gel | Cross-over, placebo-RCT | IBS patients | No difference between treatment and placebo groups | 10 |

| A double-blind RCT | IBS patients constipation | Effective in constipation, No effect on abdominal pain. | 11 | ||

| Double-blind placebo-RCT | IBS patients | No difference between treatment and placebo groups | 12 | ||

| Artichoke | Whole plant | Post-marketing surveillance study | IBS patients | Significant reductions in the severity of symptoms | 15 |

| Open dose-ranging study | IBS patients | “Alternating constipation/diarrhea” toward “normal”, significant improvement in total quality-of-life (QOL) score | 16 | ||

| Fumaria officinalis | Whole plant | Double-blind, placebo-RCT | IBS patients | No difference between treatment and placebo groups | 18 |

| Curcuma longa | Rhizome | Pilot study, partially blinded, RCT randomized, | IBS patients | No difference between treatment and placebo groups | 19 |

| Hypericum perforatum (HP) | Aerial parts | Open-label, uncontrolled trial | IBS patients women | Autonomic nervous system to different stressor, improvement of Gastrointestinal symptoms of IBS | 22 |

| Double-blind, placebo-RCT | IBS patients | No difference between treatment and placebo groups | 23 | ||

| Mentha piperita (MP) | Essence | Double-blind, placebo-RCT | IBS patients | Peppermint-oil was effective and well tolerated | 27 |

| Oil | Prospective double-blind, placebo-RCT | IBS patients | Improves abdominal symptoms | 28 | |

| Oil | Double-blind, placebo-RCT | IBS patients | Significantly improved the quality of life, improves abdominal symptoms | 29 | |

| Plantago psyllium | Seed | Placebo, RCT | IBS patients constipation | Decrease Symptom severity significantly in the psyllium group, no differences in QOL | 35 |

| Carmint (Mentha spicata, Melissa officinalis, Coriandrum sativum) | Mentha piperita, Melissa officinalis (leaf), Coriandrum sativum (fruit) | Double-blind, placebo-RCT | IBS patients | Severity and frequency of abdominal pain/discomfort were significantly lower in the Carmint group than the placebo group | 38 |

3.2. Artichoke

Some documents propose that artichoke leaf extract (ALE) is useful in curing IBS. A post-marketing supervision study of ALE for 6 weeks in 279 IBS patients was done. Considerable reductions were indicated by analysis of the data in the severity of IBS symptoms. The report of 96% of patients taking ALE shows that not only does ALE act equally or better than some therapies administered for their symptoms, but also patients tolerate it well (14). In another research, the effects of ALE in 208 IBS patients with dyspepsia were investigated. After the intervention period, analysis of data showed a significant improvement in IBS occurrence of 26.4% (p < 0.001). A significant change in self-reported usual bowel movements away from “periodic constipation/diarrhea” into “normal” (p < 0.001) was considered. It has created a significant improvement in the total quality-of-life (QOL) score (20%) in the subset after treatment (15). The study of Emendörfer F, et al., based on the active metabolites, described the antispasmodic activity of cynaropicrin, as a sesquiterpene lactone from Cynara scolymus, in the treatment of IBS (16). These studies described that ALE has a good potential in improving the IBS symptoms.

3.3. Fumaria officinalis

A few researches indicated that Fumaria officinalisis shows no beneficial effects in IBS. In a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial, 106 IBS patients were divided into three treatment groups of Curcuma xanthorriza, Fumaria officinalis and placebo for 18 weeks. The pain related to IBS was reduced in the fumitory and placebo group (p=0.81). The flatulence caused by IBS had also improved in the curcuma and placebo group (p=0.48) but it had increased in fumitory group. Overall, no significant change was seen in psychological and other IBS symptoms among the three treatment groups (17). In this study, Fumaria and turmeric showed no therapeutic effects over placebo in patients with IBS. Subsequently, it is not suggested to use these herbs in the treatment of IBS.

3.4. Curcuma longa

Turmeric (Curcuma longa) has been traditionally used in Iranian and Chinese traditional medicine for digestion, abdominal pain, bloating, and distension. A pilot study, partially blinded, randomized, two-doses, of turmeric extract on IBS patients for 8 weeks, symptomology in otherwise healthy adults was done. Approximately two thirds of all subjects reported an improvement in symptoms after treatment; there were no significant differences between groups (18). Miquel J, et al. reported that curcumin has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agents (19). In a review article by Gilani AH, et al., reported scientific basis for the medicinal use of turmeric in gastrointestinal disorders such as IBS, the data suggested that the inhibitory effects of extract of turmeric (curcumin) are mediated primarily through a calcium channel blockade in hyperactive states of the gut and airways. The efficacy of curcuma in IBS may be due to antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and spasmolytic activities (20).

3.5. Hypericum perforatum (HP)

Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s wort) has been effective in curing patients with mild-to-moderate depression (21). There were a few clinical trials to evaluate the beneficial effects of HP extract in IBS. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on 70 IBS women patients (who consumed HP) showed no significant differences between the intervention and the placebo groups (22). In contrast, a Wan H, et al. study showed that HP extract can improve the conditions of psychology and the autonomic nervous function reactivity in decreasing the stress in IBS patients (21, 23). Antidepressant activity and modulating psychological stress are the Hypericum perforatum mechanisms in relieving IBS (23, 24).

3.6. Mentha piperita( MP)

Mentha piperita has been used for thousands of years in Persian traditional medicine. The evidences for using MP in gastrointestinal disease are more than other herbal medicine (25). A number of controlled studies have shown that MP named enteric-coated peppermint oil is efficient in the treatment of IBS. In a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical study on 110 IBS patients, peppermint-oil (three to four times daily, 15–30 min before meals, for 1 month) in comparison with placebo was evaluated. Symptom improvements were significantly higher than the placebo group (p < 0.05). Thus, in this trial, peppermint-oil was effective and well tolerated (26). In another clinical study by Cappello et. al, (2007), 57 IBS patients were treated with peppermint oil (two enteric-coated capsules twice per day or placebo) for 4 weeks in a double blind study. They found that peppermint oil reduced significantly the total IBS symptoms score compared with the placebo group (p<0.01). They suggested that when peppermint oil, when given for a period of 4 weeks, is safe and effective for patients with IBS (27). In a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study by Merat et al. in 90 IBS patients Iran( 2004) that took one capsule of enteric-coated, delayed-release peppermint oil (Colpermin) or placebo three times daily for 8 weeks, they y found that the severity of abdominal pain reduced significantly in the Colpermin group as compared to controls, and Colpermin significantly improved the quality of life (p< 0.001). There was no significant adverse reaction (28). Khanna, et al, in reviewing nine studies that evaluated efficacy and safety of enteric-coated peppermint oil capsules in 726 patients IBS has reported, peppermint oil was effective in controlling the symptoms of IBS (5 studies, 392 patients) Abdominal pain(5 studies, 357 patients) was especially significant. Adverse events of Peppermint oil, were mild and transient, the major complications were reported heartburn (29). In another review study by Grigoleit HG, et. al, similar results in 16 clinical trials investigating enteric-coated peppermint oil (PO) in IBS children were observed, but average response rates in terms of “overall success” are 58% (range 39–79%) for Peppermint oil and 29% (range 10–52%) for placebo. Adverse events reported were generally mild and transient, but very specific (30). The pharmacodynamics effect of Peppermint oil in IBS may be due to 1) reducing gastric motility, 2) antispasmodic effect on the smooth muscles due to the interference of menthol with the movement of calcium across the cell membrane, 3) anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activities in the small intestine (31–33). Based on the researches, colpermin is safe and effective as a therapeutic method in the treatment of abdominal pain or discomfort in IBS.

3.7. Plantago psyllium

Psyllium is mainly used as a dietary fiber, to relieve symptoms of constipation in IBS (26). In a study by Bijkerk et. al, (2009) the dietary content of soluble fiber (psyllium, 10 g, n=85), or insoluble fiber (bran, 10 g, n=97) in 275 IBS patients were evaluated. They showed those who had three months after treatment, symptom severity in the psyllium group had reduced by 90 points, compared with 58 points in the bran group. They offered that Psyllium benefits patients with IBS in primary care (34). Bijkerk (2004) et. al, in reviewing 17 articles, reported fiber reducing IBS symptoms, particularly patients with constipation, but were not effective in abdominal pain (35). In another review study by Alexander C Ford et al., similar results in six studies were observed, but when the treatment effect was considered in the meta-analysis of these studies, there was no statistical significance (36). Future clinical studies evaluating the effect and tolerability of fiber therapy are needed in primary care.

3.8. Carmint

Carmint is an Iranian herbal remedy containing extracts of mentha spicata, melissa officinalis, and coriandrum sativum. An RCT in 32 patients with IBS showed that the severity and frequency of abdominal pain in the Carmint group was significantly lower than the placebo group (37). The pharmaceutical effect of Carmint is antispasmodic, carminative, and has sedative effects (37).

4. Conclusions

Nowadays, IBS patients are widely used as complementary and alternative medicines; especially herbal supplements. In this article, various herbal preparations and their possible mechanisms were evaluated in the treatment of IBS. Mentha piperita plays an important role in controlling abdominal pain caused by IBS. Aloe vera, curcuma, fumaria officinalis, and hypericum perforatum showed different mechanisms such as prosecretory activity, anti-inflammatory activity and inducing gastrointestinal motility, in the management of IBS. According to various parameters that affect the pathophysiology of IBS, it is believed that compound preparations containing several herbs can be more beneficial than single products. However, different clinical trials must be done to evaluate the effects of herbal preparations in IBS.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Vice Chancellor for Research (No. 910950), and Faculty of Traditional Medicine at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

iThenticate screening: July 15, 2016, English editing: August 01, 2016, Quality control: August 04, 2016

Conflict of Interest:

There is no conflict of interest to be declared.

Authors’ contributions:

All authors contributed to this project and article equally. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Hyams JS. Irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, and functional abdominal pain syndrome. Adolesc Med Clin. 2004;15(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/S1547336803000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, Guiraldes E, Hyams JS, Staiano A, et al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1527–37. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohman L, Simrén M. Pathogenesis of IBS: role of inflammation, immunity and neuroimmune interactions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7(3):163–73. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyams JS, Burke G, Davis PM, Rzepski B, Andrulonis PA. Abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents: a community-based study. J Pediatr. 1996;129(2):220–6. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(96)70246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noras MR, Yousefi M, Kiani MA. Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Use in Pediatric Disease: A Short Review. International Journal of Pediatrics. 2013;1(2):45–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahrami HR, Noras M, Saeidi M. Acupuncture Use in Pediatric Disease: A Short Review. International Journal of Pediatrics. 2014;2(3.2):69–72. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available from: http://handbook.cochrane.org. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grindlay D, Reynolds T. The Aloe vera phenomenon: a review of the properties and modern uses of the leaf parenchyma gel. J Ethnopharmacol. 1986;16(2–3):117–51. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spanier JA, Howden CW, Jones MP. A systematic review of alternative therapies in the irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(3):265–74. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutchings HA, Wareham K, Baxter JN, Atherton P, Kingham JG, Duane P, et al. A randomized, cross-over, placebo-controlled study of Aloe vera in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: effects on patient quality of life. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2011;2011:206103. doi: 10.5402/2011/206103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odes HS, Madar Z. A double-blind trial of a celandin, Aloe vera and psyllium laxative preparation in adult patients with constipation. Digestion. 1991;49(2):65–71. doi: 10.1159/000200705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis K, Philpott S, Kumar D, Mendall M. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of aloe vera for irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(9):1080–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khedmat H, Karbasi A, Amini M, Aghaei A, Taheri S. Aloe vera in treatment of refractory irritable bowel syndrome: Trial on Iranian patients. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18(8):732. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker AF, Middleton RW, Petrowicz O. Artichoke leaf extract reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in a post-marketing surveillance study. Phytother Res. 2001;15(1):58–61. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200102)15:1<58::aid-ptr805>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bundy R, Walker AF, Middleton RW, Marakis G, Booth JC. Artichoke leaf extract reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome and improves quality of life in otherwise healthy volunteers suffering from concomitant dyspepsia: a subset analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(4):667–9. doi: 10.1089/acm.2004.10.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emendörfer F, Emendörfer F, Bellato F, Noldin VF, Cechinel-Filho V, Yunes RA, et al. Antispasmodic activity of fractions and cynaropicrin from Cynara scolymus on guinea-pig ileum. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28(5):902–4. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brinkhaus B, Hentschel C, Von Keudell C, Schindler G, Lindner M, Stützer H, et al. Herbal medicine with curcuma and fumitory in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(8):936–43. doi: 10.1080/00365520510023134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bundy R, Walker AF, Middleton RW, Booth J. Turmeric extract may improve irritable bowel syndrome symptomology in otherwise healthy adults: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(6):1015–8. doi: 10.1089/acm.2004.10.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miquel J, Bernd A, Sempere JM, Díaz-Alperi J, Ramírez A. The curcuma antioxidants: pharmacological effects and prospects for future clinical use. A review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002;34(1):37–46. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4943(01)00194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilani AH, Shah AJ, Ghayur MN, Majeed K. Pharmacological basis for the use of turmeric in gastrointestinal and respiratory disorders. Life Sci. 2005;76(26):3089–105. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wan H, Chen Y. Effects of ant depressive treatment of Saint John’s wort extract related to autonomic nervous function in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2010;40(1):45–56. doi: 10.2190/PM.40.1.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito YA, Rey E, Almazar-Elder AE, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Locke GR, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of St John’s wort for treating irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(1):170–7. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. Efficacy and tolerability of Hypericum perforatum in major depressive disorder in comparison with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(1):118–27. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butterweck V, Schmidt M. St. John’s wort: role of active compounds for its mechanism of action and efficacy. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2007;157(13–14):356–61. doi: 10.1007/s10354-007-0440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahimi R, Abdollahi M. Herbal medicines for the management of irritable bowel syndrome: a comprehensive review. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(7):589–600. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i7.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu JH, Chen GH, Yeh HZ, Huang CK, Poon SK. Enteric-coated peppermint-oil capsules in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective, randomized trial. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(6):765–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02936952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cappello G, Spezzaferro M, Grossi L, Manzoli L, Marzio L. Peppermint oil (Mintoil) in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective double blind placebo-controlled randomized trial. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39(6):530–6. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merat S, Khalili S, Mostajabi P, Ghorbani A, Ansari R, Malekzadeh R. The effect of enteric-coated, delayed-release peppermint oil on irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(5):1385–90. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0854-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khanna R, MacDonald JK, Levesque BG. Peppermint oil for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(6):505–12. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182a88357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grigoleit HG, Grigoleit P. Peppermint oil in irritable bowel syndrome. Phytomedicine. 2005;12(8):601–6. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Logan AC, Beaulne TM. The treatment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth with enteric-coated peppermint oil: a case report. Altern Med Rev. 2002;7(5):410–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grigoleit HG, Grigoleit P. Pharmacology and preclinical pharmacokinetics of peppermint oil. Phytomedicine. 2005;12(8):612–6. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hiki N. Peppermint oil reduces gastric motility during the upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Nihon Rinsho. 2010;68(11):2126–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bijkerk CJ, de Wit NJ, Muris JW, Whorwell PJ, Knottnerus JA, Hoes AW. Soluble or insoluble fibre in irritable bowel syndrome in primary care? Randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b3154. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bijkerk CJ, Muris JW, Knottnerus JA, Hoes AW, de Wit NJ. Systematic review: the role of different types of fibre in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19(3):245–51. doi: 10.1111/j.0269-2813.2004.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ford AC, Talley NJ, Spiegel BM, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Schiller L, Quigley EM, et al. Effect of fibre, antispasmodics, and peppermint oil in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a2313. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vejdani R, Shalmani HR, Mir-Fattahi M, Sajed-Nia F, Abdollahi M, Zali MR, et al. The efficacy of an herbal medicine, Carmint, on the relief of abdominal pain and bloating in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a pilot study. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51(8):1501–7. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]