Abstract

Although work schedulers serve an organizational role influencing decisions about balancing conflicting stakeholder interests over schedules and staffing, scheduling has primarily been described as an objective activity or individual job characteristic. The authors use the lens of job crafting to examine how schedulers in 26 health care facilities enact their roles as they “fill holes” to schedule workers. Qualitative analysis of interview data suggests that schedulers expand their formal scope and influence to meet their interpretations of how to manage stakeholders (employers, workers, and patients). The authors analyze variations in the extent of job crafting (cognitive, physical, relational) to broaden role repertoires. They find evidence that some schedulers engage in rule-bound interpretation to avoid role expansion. They also identify four types of schedulers: enforcers, patient-focused schedulers, employee-focused schedulers, and balancers. The article adds to the job-crafting literature by showing that job crafting is conducted not only to create meaningful work but also to manage conflicting demands and to mediate among the competing labor interests of workers, clients, and employers.

Keywords: work scheduling, schedule control, staffing, health care, work–family, work hours, work–life, workplace flexibility, working time, long-term health care

“Well I just adopted a kid from [country] so why can't I have it off?” … [I say,] cause you can't, you work in nursing.

It's a lot of begging, pleading, and borrowing…. Making deals, swapping them around, do a double this day, have that day off. It's a lot of “let's make a deal.”

scheduling people is different from scheduling “things.”

—statements from three work schedulers describing their jobs

How work schedules are determined has important employment and social implications for workers and their families. Research has found that long work hours and erratic schedules negatively influence employee mental health (Geiger-Brown, Muntaner, Lipscomb, and Trinkoff 2004), employee job quality (Henly and Lambert 2014), employee safety (Barger et al. 2005), and patient care (Rogers et al. 2004). Work schedules affect work-life conflicts by influencing employees' abilities to manage child and elder care, commuting, school, household chores, and personal health (e.g., doctor's appointments, exercise, and sleep) (Kossek and Thompson 2015).

Work schedules are also a critical factor shaping work processes and staffing costs in many industries. Many employers have established a formal job—typically called the scheduler—to create and oversee employee work schedules. Managers in hospitals rely on the work schedulers to control workforce costs by minimizing staffing levels and overtime, and by frequently making changes to align work hours with fluctuations in the patient census (the number of individuals being cared for). This leads to unpredictable schedules (Henly and Lambert 2014) that schedulers must manage and to which workers must adapt their lives.

Yet in most employment research, work scheduling has been described as either a rational organizational process or an individual job characteristic, such as worker perceptions of scheduling control (Swanberg, Mckechnie, Ojha, and James 2011) or flexibility (Kossek and Thompson 2015). Often overlooked is the fact that work scheduling is an organizational role and an occupation involving actors (schedulers) who serve as the primary employer contact for controlling labor spending and allocation systems and for managing employees' time on and off the job. Schedulers influence organizational decisions on how schedules are established and bargained for, and how they reflect an increasingly important contested terrain in the employment relationship (Edwards 1979). Schedulers determine the working conditions for growing numbers of employees and are located at the employment nexus of balancing employers' demands for flexibility in labor allocation with employees' needs for flexibility in work hours to obtain the income and leisure time they need (Braverman 1974).

Through a qualitative study of work schedulers in 26 health care facilities that are part of a large U.S. corporate nursing home chain, we draw on job-crafting theory to examine how schedulers enact their role of “filling holes” to schedule workers and manage staffing coverage. Although schedulers have a formal job that, on paper, looks relatively perfunctory, we show that variation exists in how schedulers interpret the job in ways that expand its scope and influence to meet the needs of workers and the other stakeholders they serve. Our first research objective is to examine how and why schedulers vary in their use of job-crafting strategies to carry out their responsibilities. We examine how work schedulers expanded their formal scope and influence to meet their interpretations of how to manage stakeholders (employers, workers, and patients). Our second objective is to examine variation in the extent of job crafting (cognitive, physical, and relational) and the broadening or narrowing (through rule-bound interpretation) of role repertoires. Toward this goal, we identify four main types of work schedulers along a continuum ranging from balancers to enforcers. We contribute to the job-crafting literature by examining the ways in which job crafting is not just about creating meaningful work but also entails managing conflicting role demands and acting as an intermediary among employers, workers, and patients.

We focus on the health care industry because it exemplifies a prototypically challenging scheduling context. It is a labor-intensive service industry requiring 24-7 coverage. Highly regulated, with mandated state and federal regulations for patient-staff coverage ratios, these organizations have daily fluctuations in client (patient) census that affect profit margins, heightened cost pressures from insurers, and demanding jobs with high turnover.

Work Schedulers: A Critical Occupation

Work schedulers are a growing occupational group. Estimates based on Bureau of Labor Statistics data suggest that about 1.6% of employees in the United States are schedulers or have key scheduling duties (2014). Schedulers can be found in many industries, including manufacturing, retail, information technology, and health care (for occupational examples used by the U.S. Department of Labor, see categories listed in O*NET [2015a,b], such as dispatchers, and production-planning and expediting clerks). Although work scheduling is a critical occupation for the organization of work in most industries, schedulers' roles are increasingly complex and contested. Employers seek greater flexibility in the allocation of labor because of the growth of 24-7 schedules, fluctuations in market demand, just-in-time work processes, and cost pressures that lead them to try just-in-time staffing. At the same time, employees demand greater flexibility because of the predominance of nontraditional family arrangements, including single-parent and dual-earner families.

Health care and long-term care are critical cases. Hospitals and nursing homes typically have at least one position dedicated to creating and maintaining employee schedules. These work schedulers operate in 24-7 interdependent work systems, matching employees' rising personal scheduling demands with the regulated staffing ratios for direct-care coverage. Effective scheduling practices are essential for meeting legal, cost, and quality standards in health care (Kutney-Lee et al. 2009). For example, employers must comply with federal and state regulations that require minimum standards for the quantity and mix of licensed staff on duty that vary by patient acuity (Bowblis and Lucas 2012). States also regulate staffing to balance Medicaid and Medicare costs with safety standards (Bard and Purnomo 2005). For example, “a skilled nursing facility must provide 24-hour licensed nursing service … [including] a registered professional nurse at least 8 consecutive hours a day, 7 days a week” (Brady 2013b). Because labor costs represent roughly 60% of the overall operating costs in health care organizations, workforce scheduling is of strategic importance for achieving cost and quality goals (Brimmer 2013).

At the same time, competitive cost pressures require health care organizations to keep staffing levels low because Medicaid and other reimbursement and business cost margins are stressed. This means if a few workers call in sick, little staff redundancy is available to make up for the shortfall, causing increased workloads for other workers or coverage gaps. Many employers have also created low-wage, high-turnover jobs (particularly in long-term care, which lacks wage parity with similar jobs in other health care settings) that have limited career and pay ladders; a high risk for injuries; and early morning, evening, night, and weekend work shifts. Adding to scheduling complexity, the health care workforce is 90% female, including many single mothers, racial/ethnic minorities, and immigrants (50%), a majority of whom are paid at or near the minimum wage and are living below or near the poverty line (Institute for the Future of Aging services 2007). Inadequate staffing and scheduling issues are related to lower-quality patient care, higher mortality, lower job satisfaction, and higher burnout rates (Aiken et al. 2002). These conditions explain why the job of scheduler is particularly complex and difficult—schedulers must navigate the interests and demands of multiple stakeholders: management, employees, patients, and regulators.

Although some health care research has mentioned scheduling as an organizational work process, previous studies rarely have mentioned the work scheduler or discussed this position. Most studies have taken an applied, solutions-oriented perspective that often describes a particular method or scheduling system (e.g., self-scheduling, rotating shifts, or compressed workweeks) (Bard and Purnomo 2005) or consider the effects of scheduling software systems on work outcomes (e.g., quality of patient care or employee turnover) (Albertsen et al. 2014). In this study, we show that scheduling is a workplace social phenomenon in which schedulers adapt their roles to manage their interpretations of different stakeholder demands.

Work Schedulers as Job Crafters

The conceptual framework of job crafting provides a useful lens for understanding the role of work schedulers; how they are able to respond to the competing demands of employers and workers; and why variation in job-crafting strategies may lead to different outcomes for employers, workers, and clients. Job-crafting research is based on the premise that employees voluntarily act to alter their job tasks to create meaning (Wrzesniewski and Dutton 2001; Leana, Appelbaum, and Shevchuk 2009). Job crafting is defined as “the physical and cognitive changes individuals make in the task or relational boundaries of their work.… job crafting is an action, and those who undertake it are job crafters” (Wrzesniewski and Dutton 2001: 179). Researchers have identified three job-crafting forms: cognitive, physical tasks, and relational.

Cognitive job crafting involves a worker changing how he or she views the job, perhaps seeing tasks as more or less discrete or interconnected. Schedulers cognitively craft their jobs to identify with the stakeholders. Some align themselves narrowly with management's interests, seeing themselves as strictly policy enforcers; others broadly see themselves as the balancers of multiple stakeholder interests, maintaining equity among employee, employer, and patient needs. Physical job crafting involves a worker changing the scope, nature, or number of tasks conducted on the job. Schedulers, for example, would be going beyond their job description if they helped an employee with a scheduling conflict find a replacement. Relational job crafting entails a worker using discretion to shape the quality and quantity of social interactions. For example, some schedulers actively provide emotional support to help employees manage work–nonwork scheduling conflicts. By engaging in any of these forms of job crafting—cognitive, physical, or relational—schedulers change their job design and their work social environment (Wrzesniewski and Dutton 2001). In our investigation of job crafting, we found in our data analysis that some schedulers engaged in role-narrowing behaviors to adapt to their resource-constrained contexts. Such individuals demonstrated role rigidities and rule-bound interpretations of their job responsibilities to avoid job crafting, often going “by the rule book.”

Although seminal research has discussed job crafting as an activity individuals do to create job meaning, our application of this framework to schedulers extends this work to a context in which the workers face competing demands from multiple stakeholders, demands are high, and job control can be low with constantly changing organizational requirements. This view is consistent with the work of Petrou et al., who expanded job crafting to include “proactive employee behavior to seek resources” (2012: 1122) as a way to reduce job demands in challenging work contexts. Consistent with Berg, Wrzesniewski, and Dutton's (2010) study of adaptive job crafting among employees, work schedulers respond to challenges by interpreting others' expectations of them and their own perceptions of the structural constraints in their environment. An employer's success depends on the cost-effective scheduling of labor to provide quality care, through the work scheduler. Our analysis shows that engaging in job crafting in the face of stakeholder pressures enables schedulers to have a social impact beyond what their formal role might suggest.

Methods

Sample

This study is part of a larger Work, Family, & Health network study that was funded from 2008 to 2013 by a cooperative agreement between the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease control and Prevention to examine how the structure of work is linked to work-family conflict and occupational health. It involved 26 facilities in more than a half-dozen U.S. states that were part of a national private provider of short- and long-term elder care, an organization referred to using the pseudonym “Leef.” Each of the facilities provided skilled nursing, assisted living, or specialty services and employed just one scheduler (a total sample of 26 schedulers). The scheduler was a salaried employee whose job was to put together the schedule for all staff of the multiple work-site units.

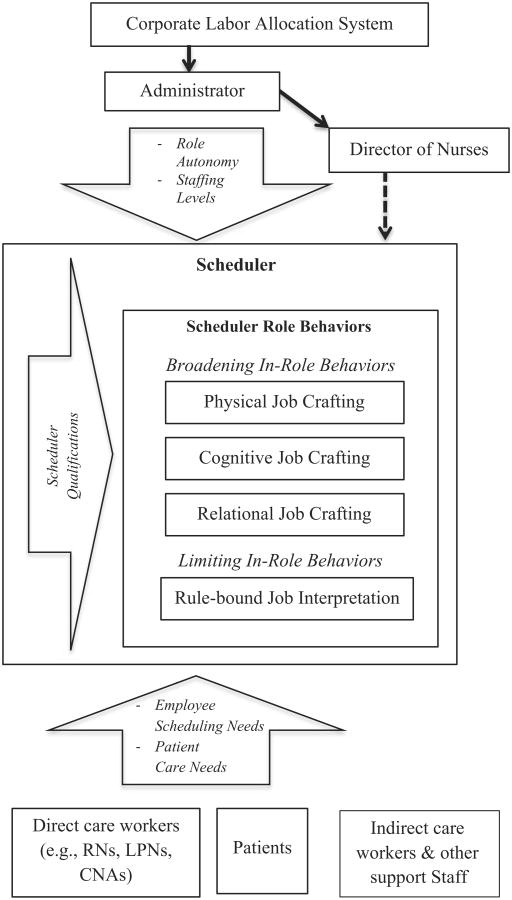

The scheduler reported to and was supervised by the building administrator, the senior line manager of each health care facility. The administrator ensured financial objectives were met following directives from a regional vice president of operations. The administrator oversaw the daily functions of the long-term care, skilled-nursing facility and all departments (e.g., Dietary, HouseKeeping, Human Resources, Finance, and Nursing). Second in command was the director of nursing (known as the DON). The DON was a nurse who supervised the direct-care staff (nurses and nursing assistants) but not the scheduler, although they often worked closely together. The schedulers were considered part of the management team and attended daily management meetings because their responsibilities were to ensure patient-care coverage and to keep the building staffed. Schedulers had an important role and a higher status in the hierarchy than the nurses or nursing assistants, but they were in a unique administrative role in that they did not supervise anyone. Figure 1 shows the schedulers' work context.

Figure 1. Work scheduling in Organizations: The Role of Job crafting in constrained contexts.

Notes: CNAs, certified nursing assistants; LPNs, licensed practical nurses; RNs, registered nurses.

The facilities typically operated with three 8-hour shifts (6:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m., 2:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m., and 10:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m.). At some sites, the shifts overlapped to allow the workers on one shift to transfer information about patients to the next to ensure continuity of care. State regulations dictated the required skill mix (the number of nursing staff with the requisite levels of training and education) in relation to the patient census. To control costs, a labor budget was allocated to each facility to administer. The scheduler was asked to limit labor costs through the effective use of scheduling and timekeeping software. The corporate office monitored the use of premium pay, such as overtime, publishing a list of sites where a lot of overtime was used to promote lower labor costs.

Data

The data are from face-to-face semi-structured interviews with 26 schedulers and 26 administrators located at the 26 long-term care, skilled-nursing facilities. Archival data on the job description and scheduling policies were also collected. The interview protocol can be found in Appendix A. The topics covered include how schedules were set, the biggest issues around setting schedules and hours, the toughest scheduling problems, scheduling strategies used, who the scheduler worked with to set the schedule, the most challenging scheduling times of the year, and policies regarding allowing time off and call-outs (last-minute requests for time off). Table 1 shows descriptive information about the work sites and the schedulers interviewed.

Table 1. Work-Site Demographics of Schedulers and Scheduling Context.

| Characteristics | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Schedulera | ||

| Age | 41.3 | 10.1 |

| Female (%) | 100 | — |

| Raceb | 0.88 | 0.33 |

| Parent or guardian | 0.62 | — |

| Number of children younger than 18 | 0.54 | 0.71 |

| Number of children older than 18 | 0.04 | 0.2 |

| Elder caregiver | 0.19 | — |

| Average weekly hours | 43.1 | 7.19 |

| Job tenure (years) | 6.48 | 7.14 |

| Married | 0.62 | — |

| Degreec | 0.73 | — |

| Workforced | ||

| Female (%) | 92.56 | 0.06 |

| Age | 38.76 | 2.54 |

| White (%) | 73.63 | 0.23 |

| Number of children | 1.01 | 0.2 |

| Elder caregivers (%) | 0.3 | 0.08 |

| Weekly hours | 37.19 | 2.31 |

| Job tenure (years) | 6.04 | 1.35 |

| Married (%) | 0.64 | 0.1 |

| Immigrantse (%) | 23.52 | 18.65 |

| Organizational | ||

| Average number of beds | 114.96 | 32.35 |

N = 26.

1 = white; 0 = other.

1 = some college/associate's degree or bachelor's degree; 0 = high school diploma/GED.

Number of employees at each facility ranged from < 100 to > 200 (average of 148).

Not born in united states.

The schedulers all worked in nonunionized health care facilities with an average size of 115 resident beds. The number of employees being scheduled at each facility ranged from fewer than 100 to more than 200 (average of 148). The workforce was largely female, with an average of one child and with one-third providing elder care. Nearly one-fourth of the workforce were immigrants. The schedulers were all female and were about 41 years old with an average job tenure of 6.5 years.

Data Analysis

We used a grounded theory approach to identify, categorize, and link themes in the data (Strauss and Corbin 1990; Locke 2002; Cresswell 2007; Giorgi 2009). This methodology allows the emergence of themes in the ways schedulers engage in job crafting and an understanding of how schedulers shaped their jobs, creating variation across what, on paper, looked like a standard scheduling role.

We read and open-coded the interviews, identifying categories of schedulers' role perceptions and behaviors. All passages were coded and recoded to saturation until no additional codes could be applied. Then we discussed the patterns among the codes and moved to axial coding (the process of relating discrete codes reflecting categories to each other) to reflect a larger concept (Cresswell 2007). This entailed classifying and further identifying themes, and aligning code definitions. Two of us performed the axial coding on job-crafting themes, discussing three transcripts to reach 100% consensus for reliability. Then the other three of us coded a subset of interviews from three sites to ensure the reliability of the thematic codes. Schedulers' behaviors for each thematic code were rated as “high,” “medium,” “low,” or “not present,” based on the frequency and consistency of their responses in the axial codes. We identified data patterns among the thematic codes to allow the final typology to emerge. At this point, we also coded the administrator interviews to triangulate the coding.

Findings: Schedulers' Job Background and Work Context

The Scheduler Job Description

To understand schedulers' job-crafting strategies, we must first examine the job description to understand what their jobs look like “on the ground.” The Leef job description for a scheduler states, “The scheduler serves as primary … contact for all employees' needs with respect to scheduling and timekeeping. … The scheduler manages, maintains, and evaluates the facility labor management process by following labor and pay policies, as well as collective bargaining agreements (if applicable)1, to optimize clinical, financial, and human resource operating results.” The schedulers work to ensure labor expenses “are at the appropriate budgeted level and volume-adjusted schedule changes are made while balancing optimal utilization of employees with consistent quality care and labor spending.” Through effective timekeeping and payroll management, the scheduler also reviews possible “leakage points” “to minimize overpayment of premium pay.” To balance these multiple (and conflicting) objectives, the schedulers' tasks are to set the schedule and grant or deny requests for schedule changes such as shift swaps, vacations, or days off.

Hiring

The schedulers came into their position in a variety of ways. The position has no requirement that applicants have a nursing background. Advertisements call for experience in business or health care administration or psychology, and for administrative experience with payroll or compensation or scheduling. Only 2 of the 26 schedulers whom we interviewed had previous scheduling experience. some nurses or nursing assistants become schedulers to earn higher compensation or for physical reasons, but this is not part of a career ladder. Eight of our schedulers had previously been certified nursing assistants (CNAs), most working in the same home. Experience was not always the catalyst for moving into the scheduling role, however. One scheduler was appointed because a broken bone reduced her to light-duty work.

To hire schedulers, the organization advertises for people with strong planning, organizational, interpersonal, and leadership skills who “thrive on working in [a] highly structured, compliance oriented position.” Thus, the role expectations and job description themselves have contradictory demands. Being able to balance multiple objectives and having leadership skills require considerable independent judgment, but the legal and organizational structures constrain independent decision making. Yet what the job description does not specify is the exact manner in which these duties must be carried out, leaving considerable flexibility in what schedulers can do to craft their roles across facilities. When jobs have contradictory demands by definition, they create the opportunity for workers to interpret the job—or craft the job—in distinct ways. Thus, schedulers walk a tightrope to meet the demands of multiple stakeholders while working within the legal and organizational constraints.

Work Context: Hole-Filling, Autonomy, Understaffing, and Scheduling System

As background on the work context, in this section we augment schedulers' interviews with those from their supervisors, the administrators.

Hole-Filling

The schedulers we interviewed emphasized the need to minimize budget impacts and to maximize the quality of patient care while doing what they referred to as their most critical job task: hole-filling. Schedulers used the term hole-filling to describe their responses to the understaffed hours in the regular schedule (holes): 1) unplanned gaps that occur because of employees' call-outs (e.g., last-minute requests for time off because of their own or a family member's illness), 2) planned gaps that occur because of employees' requests for time off, and 3) gaps that occur as a result of staff turnover or facility growth. One Scheduler, Elise, described the process of setting up the facility's permanent schedule: “when they hire [someone], I look at what I already have as a current master schedule, and I identify where the holes are, which units the holes are on, the shift, etc.” Based on the openings, or holes, in the schedule, schedulers identify regular shifts for new employees. In line with the uncertainty that holes in the schedule create, Anju, another scheduler, stated, “The master schedule is best thought of as a scheduling framework.” She emphasized that, although she works ahead of time to address scheduling needs, last-minute changes always require her to act immediately.

I usually get pretty much all the holes filled a month in advance. It's those last lingering ones that take me a while or somebody comes to me this week, the schedule is done, [and says they're] gonna be out on emergency, vacation, or anything like that, then I work on it as soon as possible.

Autonomy

Although the schedulers we interviewed worked within constraints (legal regulations and organizational policies) to fulfill their role, they reported a degree of flexibility or autonomy in how they carried out that role. We coded statements about the schedulers' ability to use personal discretion, their level of decision-making autonomy, and their formal and informal power.

We then compared the schedulers' autonomy codes with the administrators' responses to the question “What is your involvement in scheduling?” Their responses were coded as “high,” “medium,” or “low.” The administrators' assessments of their involvement in scheduling were generally coded lower when the schedulers were coded as “high” in autonomy. The opposite is also true; for example, Dana was coded as “low” in autonomy because she said, “[The administrator] helps out,” and this was also reflected in her administrator's response: “My involvement now is kind of high.”

Overall, schedulers reported a high degree of autonomy in carrying out their job tasks; in most cases, schedulers were expected to handle the schedule largely on their own. sometimes, they consulted with a manager, such as the DON, to approve vacation requests or disciplinary actions, but most had considerable decision-making authority over scheduling. As Elise stated, “The actual physical [writing] of the schedule, it's me who's sitting there looking at what the future holes are and trying to find a way to resolve [them]. Just me.” Other schedulers echoed this assessment of autonomy, including Faye who said,

I really do all of the scheduling … sometimes run things by [the director of nursing], if it's more like performance issues … but if I'm hiring a new employee into the building, I have my parameters and I am consistent, no matter who walks in the door, if you're part time or full time, you work every other weekend, so, as long as I'm following my parameters, I do it independently. I don't get a second opinion about it; I don't run it by anybody. I'll just inform them of what I've already done.

But another, smaller cluster of schedulers reported more involvement from others, which both facilitated and hindered autonomy. Neva advocated for the human resources manager to assist her so that another person in the building would be able to respond to scheduling concerns, and so afford her more autonomy.

I did show her how to do the schedule. She's supposed to be my backup. If I'm not able to work, she is my backup for payroll and scheduling.

In contrast, Aleah reported experiencing a larger degree of involvement, often unwanted, from others at the facility, which reduced her sense of autonomy.

The administrator [and] the director of nursing are the two that I work with mostly [on the schedule] …. they play an interesting role…. they play too much of a role…. they sort of take control.

Understaffing

Four schedulers indicated that their facilities were very understaffed. They continually did not have adequate staff to keep the schedule filled, which made scheduling difficult. As Klara stated:

What I'm trying to fix is that there's just not enough staffing. As soon as people are hired, other people leave for various reasons, so it's hard to get up to full staffing, and I think once that happens, it's going to be so much better.

Fourteen of the schedulers we interviewed were coded as working in a facility with low or moderate levels of understaffing. Eight schedulers (about one-third of the facilities), however, did not mention understaffing.

Many of the administrators' comments regarding understaffing were consistent with those of the schedulers. For example, Anju was coded as being in an adequately staffed facility, and her administrator's responses were consistent: “I think that our labor is more controlled in this building, my turnover is low, my overtime is low, my open positions is low.” Also, in another facility, which was described by the scheduler as chronically understaffed, the administrator said that they “faced a scheduling crisis every day” in trying to find coverage.

Corporate Labor-Allocation System

The administrators described the corporate labor-allocation system provided to schedulers. This system is a formula used to determine the goals for the number of hours per patient day (HPPD)2 in terms of scheduling the direct-care staff to “budget and manage nursing dollars and hours” (Brady 2013a). This formula is derived from state regulations mandating the minimum staffing levels based on the number of patients and their nursing-care acuity needs. Although all administrators referred to the HPPD goal as handed down from corporate, some variation existed across the 26 facilities in the level of discretion administrators perceived they had in allocating these hours. Some administrators felt very constrained by the corporate guidelines. At one facility, the administrator bemoaned that the HPPD was adjusted according to the current occupancy rates.

You got four empty beds upstairs; you got four empty beds downstairs, that's why. That should be easily eight hours a day right there. The frustrating part is you know there's like a formula where basically … for every empty bed we would cut four hours. You can't keep doing that and provide care. And that's where my biggest loss of sleep is. I'm held to that standard. But I'm not putting people at risk.

Still others perceived considerable latitude and discretion to be possible. As one administrator explained:

Our company kind of leaves the scheduling to us at the facility level. Obviously there's a [H]PPD that we are expected to follow. It's a budgeted [H]PPD. We have targets. We are always looking at premium time, late-ins, late-outs, punching for lunch, those kinds of things are all part of the day. because there is an expectation, and we want, you know, to be where we need to be as well, but scheduling time off or vacations or that sort of thing is really up to us, as long as we try to meet our [H]PPD, which is really what they look at, at corporate.

One administrator even talked about putting in a secret parallel scheduling system to get around the labor-allocation system. He stated,

I think we do things on our own that we then have to create secondary systems for because there is no room for creativity within the systems that [corporate] has put together regarding labor management. So anything that you want to do to really fit the unique needs of your building you have to do sort of hush-hush on the side.

Findings: Job Crafting

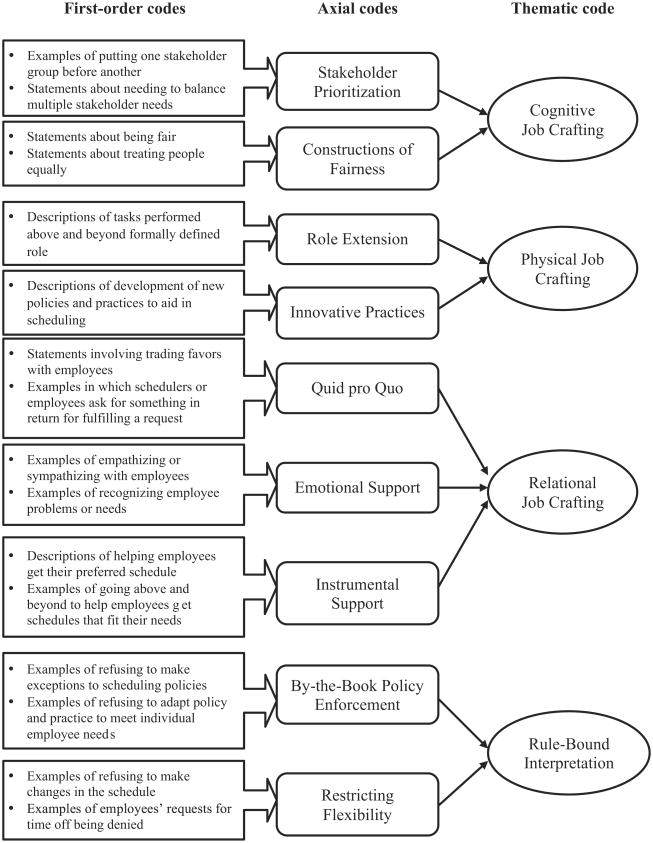

Let us now turn to our first research question: How and why do schedulers use job crafting to perform their jobs? Figure 2 shows our codes pertaining to job crafting. We found evidence of the schedulers in all 26 sites engaging in all three types of job crafting (cognitive, physical, and relational). We group these codes into two larger categories: 1) broadening role behaviors, which consists of the three types of job crafting that expand what the scheduler does, whom she interacts with, or how she interprets her role, and 2) limiting role behaviors, which consists of rule-bound interpretation, that is, the extent to which the scheduler focuses on interpreting her tasks as defined by the company for the position and the written scheduling policies or practice.

Figure 2. Scheduler job crafting codes for formal and informal roles.

Broadening Role Behaviors

Cognitive Job Crafting

Two axial codes—Stakeholder Prioritization and Constructions of Fairness— form the cognitive job-crafting theme (how schedulers viewed the job and saw their roles as more interconnected or as separately focused).

Stakeholder Prioritization describes the stakeholder(s) on whom the scheduler is primarily focused; the stakeholders include employees, patients, and the employer. Last-minute scheduling deviations inevitably occur as employees request time off or personal schedule changes. A minimum number of staff per patient are legally required to provide appropriate care, particularly in units with higher levels of patient acuity. Schedulers must know the current patient census and provide adequate staffing to meet legal and patient needs, and to anticipate fluctuations. The employer, as an entity that seeks to minimize staffing costs, pressures schedulers to minimize overtime and use the cheapest available labor.

These three needs (employee scheduling satisfaction, adequate care for patients, and reduction of labor costs) are often in conflict. Because schedulers try to stay close to the exact number of staff members on the schedule that they need, any deviation from expectations can create the need to compromise in other areas. For example, a typical conflict occurs when too many employees have called out from work on a particular day. The scheduler must consider the current census and decide whether to shuffle employees between units with fewer staff working than expected or, alternatively, to bring in either a current staff member who is not close to going into overtime or one who is at an overtime premium. A final option is to bring in a per-diem individual (an on-call, temporary, licensed skilled nurse or CNA from an agency) to fill in at a higher hourly rate than the regular employees.

This tension among the multiple stakeholders was evident in the interviews. Although faced with the same balancing act, schedulers reported a wide variation in priorities. For example, when faced with a conflict among labor costs, employee scheduling preferences, and patient care, nine schedulers indicated that they considered labor costs ahead of the other factors: “I always look at labor cost, yeah, labor cost goes first” (Anju); “In my view, it would be labor costs” (Kayla). By contrast, seven schedulers placed a premium on patient or resident care: “Resident care is number one” (Neva). Only two schedulers considered the employee scheduling preferences to take priority. Corina stated, “[Employee] scheduling [Preferences] definitely take priority over … labor costs.” Eight schedulers were balanced, considering two or all three stakeholder needs simultaneously. Gwen described her conflict associated with a balanced approach: “The biggest issue is trying to please everyone…. Give them their time off requests and still maintain adequate staffing.”

Constructions of fairness, the second dimension of cognitive job crafting, concerns beliefs about fairness—in particular, in vacation scheduling, holidays, and time-off requests—and was a key theme that influenced the way schedulers interpreted and enacted their roles. Neva highlighted this challenge to remain fair: “It's hard. You have to come up with a system because [those with] seniority should get something for being here for so many years. … Gotta try to be fair.” From her perspective, fairness resulted in employees with higher seniority having greater access to preferred scheduling. In contrast, Aleah reported that, although “it's all about fairness,” fairness was based on previous scheduling decisions in terms of who had worked which holidays in the past. Althea represented another take on fairness, commenting that in the case of call-outs and requests for time off, employees should be treated equally.

Even if there's an employee [whose] family member is sick … [and] they call out one day and then they're here for a week and then they have to call out again … we suggest they take a family medical leave or a personal leave, because you have to be [equal] across the board. You can't treat one case differently than the other.

Overall, schedulers sought to develop scheduling systems that were “fair” to employees, although they interpreted fairness in many different ways.

Physical Job Crafting

We use two axial codes—Role extension and Innovative Practices—to encompass physical job crafting (actions schedulers took to change the scope, nature, or number of their job tasks).

Role extension was applied to passages in which schedulers said they performed tasks outside their formal job description. Elise, for example, reached out to other facilities for per diems and created a performance-improvement plan for employees who were at risk of being disciplined for having frequent call-outs. Althea created a list for supervisors to use while she was not working because, during the night, supervisors also received last-minute call-outs. This list designated which employees were willing to work at the last minute and would not go into overtime hours by doing so. A majority of schedulers (16 out of 26) did not engage in any additional tasks outside the direct scheduling of employees, and overall, Role extension was limited to a few simple tasks.

Yet nearly one-third created Innovative Practices, their own policies and practices to minimize the future appearance of scheduling holes. These were commonly found around annually recurring problematic times such as holidays and summer vacations and usually involved distributing days off using a criterion such as alternation, seniority, first-come first-served, or preference rankings. Althea used a preference-ranking holiday sign-up sheet.

September, I know it seems a little soon, but we put out a list…. we kinda check off the two [days] that they wanna work and then the one [day] that they really wanna have off and then we kind of grant that one [day] that they want off.

Innovative Practices allowed these creative schedulers to plan ahead and minimize the impact of these events on the schedule and the quality of patient care. Neva posted a calendar of vacation requests as they were filled. “They went right to that calendar, looked at it to see in the summer, ‘Oh, she's got July 4th week. Alright, I'll do the next week.' It was easy.” Other examples included Elise's implementation of split shifts to accommodate employees' preferences to attend to personal needs related to family or themselves during the workday.

Autonomy was a key contextual factor influencing both physical and cognitive job crafting. schedulers without autonomy had much less freedom to craft their own scheduling policies. schedulers who had low autonomy did not seem to be aware that creating new policies was an option; they reported that in a crisis they asked the DON or the administrator for his or her opinion. Their cognitive job crafting often represented the administrator's concerns, which were generally focused on the employer rather than employee level. Overall, schedulers who had low autonomy were more likely to conceptualize their role having employer outcomes take precedence over those of other stakeholders (employees and patients).

Relational Job Crafting

Three axial codes—Quid pro Quo, emotional support, and Instrumental support—make up the relational job crafting theme (using job discretion to increase the quality and quantity of workplace social interactions).

The Quid pro Quo codes describe a reciprocal social exchange used by the scheduler. generally, schedulers engaged in this type of relational job crafting to leverage favors of time off to fill other, upcoming holes in the schedule, especially on weekends and evenings, which are traditionally plagued with more call-outs. Of the schedulers we interviewed, 11 reported no instances of Quid pro Quo exchanges, 6 were coded as “low,” 3 as “medium,” and 6 as “high.” Althea explained, “If you don't help them, they're never going to help you. And that's the mind-set that I have if I can go the little extra mile for them, they'll help me.”

Emotional support was coded when the scheduler provided sympathy or empathy for employees. Emotional support was less frequent among schedulers than other factors, with 12 schedulers showing none and 5 coded as “low,” 2 as “medium,” and 7 as “high.” Elise was one scheduler who saw herself as providing high levels. “I'm very caring and compassionate for the staff, I'm an advocate for them, and I go to bat for them 100%…. I try to recognize them.”

Instrumental support included instances of the scheduler either arranging one-time schedule changes, such as a day off or a call-out for a shift, or more permanent schedule changes, such as switching the scheduled days of the week. Permanent schedule changes also involved adding or dropping hours to accommodate workers' needs, including enrollment in college classes and religious observances.

I have a few people for religious reasons that do every Sunday instead of Saturday because saturday's their sabbath day. so if they're willing to do every one day, then I do accommodate that instead of every other two days.” (Elise)

One-time schedule accommodations were usually related to call-outs. Althea was usually willing to help accommodate requests, even when they were made on short notice: “like I said, 99.9 percent of the time I can do it. because the person I helped yesterday is able to work tomorrow.”

Staffing levels influenced the schedulers' abilities to engage in certain types of relational job crafting. Understaffing often compelled schedulers to make exceptions to disciplinary policy because they could not afford to fire people without becoming even more short-staffed. but schedulers in understaffed facilities were unable to make other policy exceptions for employees because the number of employees available to fill holes was low. They often ran into higher labor costs because of this; as Klara describes, “I think the biggest problem is, because we're so short staffed right now, in order to fill, not only the call-outs, but the normal shortages we have due to the open positions, they create overtime.”

Limiting Role Behaviors: Rule-Bound Interpretation

Rule-bound interpretation is the degree to which schedulers were less permissive compared to other schedulers in bending the formal work policies regarding scheduling, flexibility, and time off for employees. such behaviors were enacted to limit role broadening. We use two axial codes: By-the-Book Policy enforcement and Restricting Flexibility.

By-the-Book Policy enforcement was coded when an existing informal or formal, site or organizational, schedule-related policy was upheld to the written letter with only extremely rare exceptions being made. Of our schedulers, 11 were coded as “high” and another 11 as “medium.” Only four schedulers were coded as “low,” that is, as rarely enforcing the scheduling policies. extending vacations past the permitted two weeks so that immigrant employees could visit family abroad was a typically mentioned example of ignoring a policy, although the number of such exceptions was low. Corina reported that exceptions to the two-week limit were “not likely” but that she “did have an aide who used to take a month off, who was going to [country] to see her family.” Another typically mentioned, but infrequently offered, exception was forgoing discipline for cooperative employees who were facing personal issues. Making disciplinary exceptions helped support employees who had legitimate or uncontrollable reasons for their attendance problems. Klara reported several disciplinary exceptions for call-outs.

If somebody calls out due to …they're in a car accident. We don't count that against them. you know, that's absolutely out of their control and they shouldn't be penalized for being in a car accident.

Restricting Flexibility, the second axial code for rule-bound job interpretation, was coded for passages describing the denial of requests for time off, for the timing of holiday or vacation leave, or for changes in schedules. numerous reasons were reported for denying a request, but all were based on ensuring other stakeholder needs were met. employee requests that would result in inadequate patient care or those that could be covered only by incurring higher labor costs were usually denied. When asked if she ever denied requests for time off, Aleah responded, “yeah, I deny them quite often…. They don't give me enough notice or I'll deny it at first and send it back to them saying that they need to find coverage.” Two schedulers did not discuss Restricting Flexibility, and 10 were coded “low,” 6 as “medium,” and 8 as “high.”

We used the administrators' interviews to triangulate the rule-bound interpretation codes. Administrators described the degree of leniency and autonomy they gave to employees to act independently and deviate from the handbook rules. For example, Aleah's administrator stated, “the rules for vacations and sick time and holiday time are pretty cut and dry, and so we don't really deviate from that.” In contrast, the administrator at klara's facility (klara is a scheduler who rarely enforced policies) also described exceptions: “We have a person, a nurse on one unit, who put in for her honeymoon and I said, ‘We have to give that to her.’”

A Scheduler Job-Crafting Typology

Let us now address our second question: how do the different job-crafting and rule-interpretation strategies relate to perspectives? We found evidence of variation in the patterns of the breadth and nature of job crafting and rule interpretation, yielding four ideal types: enforcers, patient-focused schedulers, employee-focused schedulers, and balancers. To identify the typology configurations, we further coded each scheduler as being either “low” or “high,” based on the extent of physical job crafting, with higher levels being considered broader. because of the greater variation in the extent of relational job crafting and rule-bound interpretation, these were categorized based on their axial codes as “high,” “moderate,” or “low.” The extent of cognitive job crafting, based on which stakeholder they most identified with, also contributed to each configurations. Table 2 shows the defining axial codes for job-crafting patterns and rule-bound interpretation that create the four unique configurations. In Appendix B, we identify each scheduler and her job-crafting patterns and rule-bound interpretation ratings used to determine her placement in the typology.

Table 2. Typology of Work schedulers as Job Crafters of Employment-Echeduling Practice in Health Care.

| Lowest use and breadth of job-crafting strategies |

|

Highest use and breadth of job- crafting strategies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Scheduler job-crafting patterns | Enforcers (n = 9) | Patient-focused schedulers (n = 7) | Employee-focused schedulers (n = 2) | Balancers (n = 8) |

| Cognitive job crafting | Highest focus on employer corporate interests and cost minimization as scheduling driver | Highest focus on patient-care needs as primary scheduling driver | Highest focus on worker-scheduling needs as primary driver | High focus on harmonizing needs of multiple stakeholder (employee, employer, patient) interests |

| Physical job crafting | Low use | Low use | Low use | High use |

| Relational job crafting | Low use | Moderate use | High use | High use |

| Rule-bound interpretation | High | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Example | “Someone just put in now a request…. I had to deny it because somebody already put in, I'm already down two nurses on vacation so I couldn't open a third hole.” (Anju) | “And not that we want to overly accommodate everybody, we really need to look at the residents first.” (Petra) | “Our policy says that they need to give—well, vacation is 8 weeks, but I feel that we're really, really easy going on that. If a person wants to go on vacation next week, I would do my very best to cover it for them.” (brisana) | “I will go into overtime even though it's really [not encouraged], to keep the floor covered. It's for resident care purposes, and it's also for the staff purposes. so when push comes to shove, I do choose the care and the staff morale over the budget.” (Elise) |

The typology highlights the relationships between the job-crafting and rule-interpretation strategies and their extent. For example, our results show that enforcers engaged in the highest degree of rule-bound interpretation and the least job crafting, whereas balancers employed the most job crafting, broadening their role repertoires. This variation in the three types of job crafting also correlates with the typology's extremes. For example, enforcers engaged in little or no relational or physical job crafting; when they did engage in job crafting, they focused on cognitive job crafting, often to minimize labor costs or to follow the rules. by contrast, balancers engaged in all types of job crafting.

Enforcers

The first ideal type, the enforcers, are most common (nearly one-third of the 26 schedulers) and are largely homogenous in their job-crafting configuration; a clear majority of these schedulers exhibited low relational job crafting and limited physical job crafting. They generally exhibited the lowest levels of job crafting overall. enforcers are also focused on the needs of the employer above other stakeholders and are not very accommodating to employees' scheduling requests. enforcers follow company policies closely and have a high level of rule-bound interpretation.

As previously noted, corporate policies discouraged use of overtime, even when it would have helped schedulers staff the site more fully and improve the quality of care. because overtime use was tracked by the corporate office and the list of those scheduling too much overtime was sent to the site leadership and schedulers, a number of enforcers clearly indicated that they did not want to be on the list. Thus, concerns about being publically identified as a poor performer may have bounded their level of job crafting.

Anju typified the enforcer perspective, stating that “labor cost goes first.” she became sensitive to labor costs after being reprimanded for her overuse of overtime to remedy understaffiing. she also had a low level of autonomy, reporting that she asked for permission (from the administrator) to grant employee requests of more than a week off for vacation and to cut the numbers of employees if the census was low. unlike high relational-job-crafting schedulers, Anju made no exceptions for vacation and often denied workers' requests for days off. This helped her reach a high level of schedule coverage: “I usually get pretty much all the holes filled a month in advance.” employees in this facility also more firequently had their requests denied. “someone just now put in a request…. I had to deny it because somebody already put in, I'm already down two nurses on vacation so I couldn't open a third hole.”

Patient-Focused Schedulers

The second unique type, patient-focused schedulers, were also common (n = 7). These schedulers generally prioritize patients over other organizational stakeholders but are usually empathetic and accommodating to employee needs for flexibility if doing so will not reduce the quality of resident care. They exhibit a moderate level of relational job crafting overall. Rather than using creative scheduling practices to help accommodate employees (i.e., physical job crafting), they rely on moderate levels of rule-bound interpretation by frequently citing formal policies as a rationale for denying requests for scheduling changes to keep adequate staffing and, thus, maintain good patient care.

As Faye, a patient-focused scheduler who exhibited a moderate level of relational job crafting, explained, “I can't leave the schedule short. If you come to me with a solution that works, then you can have the time off. but until that time, no.” Patient-focused schedulers such as Faye also tended to be more sympathetic to and lenient in disciplining employees who might have to miss work for family or personal needs—but, again, only to a point.

I like to say that I'm fair and that I treat everybody equally, but in that case I can't be that rigid…. if I have an employee that's going through a difficult period of time for whatever reason, it's not okay, but I might let them slide one or two times.

Employee-Focused Schedulers

The third type, employee-focused schedulers, were the rarest, with only two observed in our sample. both were similar in their job-crafting configurations, exhibiting high relational job crafting, low physical job crafting, a cognitive-job-crafting employee-stakeholder orientation, and low use of rule-bound interpretation behaviors. These schedulers granted almost any employee request, made frequent exceptions to scheduling policy, and often repaired the resulting damage to the schedule using overtime.

Brisana, an employee-focused scheduler, reported that she frequently accommodated employee requests, for example allowing vacations on short notice.

Our policy says that they need to give—well, vacation is 8 weeks, but I feel that we're really, really easygoing on that…. If a person wants to go on vacation next week, I would do my very best to cover it for them.

She also, as a result, exemplifies a high use of overtime and allowing more call-outs. “I'm guilty of it, but you just want to solve that problem…. you're going to take the first person you can get.” These schedulers may be rare because their overuse of overtime is considered an indicator of poor performance by the organization. Thus, these schedulers must quickly move to a more employer-stakeholder focus or risk termination.

Balancers

The fourth ideal type, balancers, regularly try to balance employer, employee, and patient needs. Just under one-third of the schedulers (n = 8) were in this category. These schedulers exhibit the highest overall levels of job crafting and seek to maximize desirable outcomes across all scheduling stakeholders. They are not only high in relational job crafting but are unique in that the majority (75%) of balancers are also high physical job crafters, expanding the breadth of their tasks.

The balancers in our sample were often more aware of opportunities to appease multiple stakeholders and were better at finding creative solutions to scheduling problems. Althea used Quid pro Quo relational job crafting. “One hand washes the other. If I slam the door on your heels I'm never going to get my schedule full. you really gotta work with them.” she granted every request she could, regardless of the policy, but was able to leverage her supportiveness into a social exchange in which the employees helped her fill the schedule in return. because of this, overtime was rarely needed, and the schedule was usually full. Whereas some schedulers used overtime freely, Althea's balanced approach allowed her to resort to overtime only “if you're in a pickle.” Another example of a balancer is Neva, who also used a combination of job-crafting strategies, including relational job crafting (showing emotional support) and physical job crafting (expanding her role to ensure she always had a ready supply of per diems), with moderate use of rule-bound interpretation (ensuring some policy adherence simultaneously). “The nurses do get stressed and do come and say, ‘I need another day off next week. I'd rather work four instead of the five.’ I say, ‘Okay, let me call a per diem and see what we can do.’” schedulers who deny requests for time off may find that the employee then calls in sick, so they are faced with a last-minute schedule hole rather than an absence they could have planned for somewhat in advance.

Unlike employee-focused schedulers, balancers put limits on employee requests. neva allowed days off only when room was available in the schedule. “I have two people out that are out ‘cause of workman's comp, I have a girl on vacation. I said, ‘I really, I can't give you up. I can't!’” because of neva's breadth of job-crafting strategies, she was better able to track employee requests and schedule to fill holes, resulting in a better balance of stakeholder needs. some balancers tried to keep extra staff on the schedule based on their knowledge of patient needs and the demands on staff at different times during the day, even when the HPPD formula suggested a decrease in staffing was necessary. Elise admitted that she

sacrifices [her] budget a little too much if it comes to staffing. I will go into overtime even though it's really [not encouraged], to keep the floor covered. It's for resident care purposes, and it's also for the staff purposes. so when push comes to shove, I do choose the care and the staff morale over the budget.

Many balancers, including Neva, used Innovative Practices to help smooth the scheduling process: “(I have) a basket on my door they can put notes in…. now I say, ‘Write it on a piece of paper’ because I get hundreds of requests.” Many of these practices were based on constructions of fairness and procedural justice rules (seniority, turn-taking, or first-come first-served). Elena adhered to discipline and attendance policies because of concerns about fairness.

I've had employees call me before and say, “can you find somebody to pick up the shift for me?” but, because it's really important to be fair and consistent, I have to tell them, “If I'm finding somebody, you just called out. so are you calling out?”

Last, our analysis shows that schedulers' past experiences were related to their cognitive job-crafting strategies. notably, schedulers who had previously worked as nursing assistants were more likely to balance the priorities of the stakeholders (five of the eight schedulers with previous nursing experience) and to be categorized as balancers in terms of overall configurations or type. Their previous experiences in the facilities led them to better understand the needs of both employees and patients, making the needs of these stakeholders more salient than those of the employer overall. For example, Tania prioritized employees and patients over budgeting to limit overtime: “coming from a CNA background, I know how it's hard to put the resident, give them the care they need when you're working short.” yet variation did exist even among those balancers with previous nursing experience; when she was asked whether patients, employee needs, or budget concerns took priority, Audrey said, “speaking as someone that used to work on the floor, I would say what the employee wants.”

Discussion

In this study, we investigate how and why schedulers use job crafting as a strategy to manage conflicting demands and mediate the interests of employers, workers, and patients. The schedulers' interpretation of their jobs as harmonizing these differing concerns plays a critical organizational role in how the scheduling process is enacted. We developed a job-crafting typology that shows how schedulers varied in their interpretations of their formal job description and ways of managing multiple stakeholders: enforcers, patient-focused schedulers, employee-focused schedulers, and balancers. each type varied in the rationales for, the degree of, and the forms of job crafting used.

We find that schedulers differ in the extent to which they engage in rule-bound behaviors. Whereas some schedulers (enforcers) follow the employer's rules closely, others (balancers) use job crafting to balance all stakeholders' needs. To employees, the scheduler becomes the face of the organization in regard to setting their working hours. To managers, the scheduler is an extension of employer interests. For patients or residents, the scheduler influences the level of care they receive. The scheduler's ability to manage these trade-offs is necessary for organizational effectiveness.

Contributions of the Study

In this study, we expand the concept of job crafting beyond the idea of creating a meaningful job (Wrzesniewski and Dutton 2001). Our findings suggest that the schedulers who are most adept at balancing the competing stakeholders' needs tend to engage in more job crafting and to use a broader repertoire of crafting behaviors (physical, cognitive, and relational). This is consistent with studies that show job crafting as an adaptive, relational process (berg et al. 2010).

In this article, we also address the need for research on workplace flexibility to integrate organizational behavior theory and to better understand the complex social dynamics of matching employer, patient, and employee work-hour demands. scheduling control has been treated mainly as an individual-level job characteristic, but we demonstrate that it is, in fact, a key aspect of the employment relationship that plays a potentially critical role in employee well-being, and in job and organizational effectiveness. Previous research has shown a link between demanding work schedules and adverse mental health events among nursing home employees (Geiger-Brown et al. 2004). Other studies demonstrated that nonstandard scheduling may result in sleep problems among nursing home employees (Takahashi et al. 2008). Managers in organizations need to understand the relationship among labor-cost-minimizing scheduling decisions, worker health, and patient quality of care. Perhaps rigidly enforcing discipline and rules, and viewing scheduling as a short-term labor-cost-reduction transaction, may have long-term negative patient care and employee outcomes.

We also show that scheduling is an art and a science, involving both formal and adaptive role behaviors in contexts that can include both predictable and unpredictable dimensions. The organizational and health care literatures have described work schedulers as individuals who plan far in advance based on projected patient needs and mandated staffing levels in predictable environments. Our findings show that in reality many schedulers face unpredictable circumstances that often necessitate that they schedule workers on the fly. If the acuity of a patient changes and that patient requires one-on-one attention, this represents a shift in the demand for resources. circumstances external to a facility also require schedulers to quickly and creatively respond to staffing gaps. For example, inclement weather may result in a spike in call-outs because of driving conditions or school closings.

Consistent with research on workplace social support, we show in this study that schedulers, like supervisors and coworkers, enact support and control in important ways that affect employees and the organization (Kossek, Pichler, Bodner, and hammer 2011). Future research should examine how schedulers use specific job-crafting behaviors to support and control employees. schedulers can serve as informal supervisors who approve schedule changes; as coworkers who make decisions on how to support colleagues; and as interpreters of organizational policies, regulations, and practices.

Implications, Limitations, and Conclusions

Future studies should analyze which job-crafting configurations are more effective for different stakeholder outcomes across health care contexts (e.g., nursing homes, hospitals, and walk-in urgent-care clinics). Other industries with varying scheduling processes, levels of resource constraints, and governance structures (e.g., union and nonunion) should also be examined.

Changing workforce demographics and the growing workplace-worker mismatch between work hours and work demands makes balanced scheduling critical for worker well-being and organizational effectiveness. Practical strategies need to be developed to train schedulers on how to better enact worker well-being and organizational effectiveness to better serve competing interests. Workplace scheduling that is a win-win for employees, patients, and the organization is needed. Training can help stakeholders learn how to develop integrative workplace solutions. As greater numbers of people require long-term health care, efficient scheduling will become critical for the recruitment and retention of health care personnel during staffing shortages.

Although the position of scheduler may seem straightforward, merely requiring the scheduler to fill holes in work shifts, its complexity and significance may have been understated. The workers who staff health care facilities are primarily women, including many immigrants, single parents, and lower-wage workers, who may not have much flexibility or many options for dependent care. scheduling decisions affect the health and well-being of not only the staff and the patients but also of their families (Clawson and Gerstel 2014). schedulers who are rule-bound interpreters or who minimize the needs of nonemployer stakeholders may cause greater stress and overload for employees and hinder work quality.

The demands on the work scheduler to maintain coverage and the need of the employees for flexibility can be framed as organizational constraints on managerial choice, customer service, and productivity. Policymakers and managers can benefit from this study and can reframe and leverage workplace scheduling to foster employee engagement, positive workplace employment relations, and improved patient outcomes.

One major limitation of the study is that, although the data are from 26 distinct facilities, the sample of schedulers is drawn from one large corporation and its 26 administrators and the data are from short context interviews. Our study represents a first step in revealing how schedulers socially construct their jobs and how schedules are made. because of the data limitations, other important aspects of scheduling may not have been fully elicited by our questions or spontaneously provided through the schedulers' answers. Moreover, most of our data were collected from the schedulers and reveal only their perspectives; therefore, future studies should empirically test the relationships we have qualitatively identified in this study and relate job crafting and the job-crafting typology to outcomes using data collected from patients, coworkers, and employers.

Future research should also examine whether schedulers in facilities that are understaffed or “under–human resourced” or in those with sanctions against overtime use are more likely to engage in less job crafting or in counterproductive job crafting and to be less supportive and more controlling. such research would view scheduling as a dynamic multilevel organizational process related to the transformation of the way work is structured and scheduled in relation to changing market, patient, employee, and employer demands.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted as part of the Work, Family, & Health Network, which is funded by a cooperative agreement through the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (Grant # U01HD051217, U01HD051218, U01HD051256, U01HD051276), National Institute on Aging (Grant # U01AG027669), Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (Grant # U010H008788). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of these institutes and offices. Special acknowledgment goes to extramural staff science collaborator, Rosalind Berkowitz King, PhD (NICHD) and Lynne Casper, PhD (now of the University of Southern California) for design of the original Workplace, Family, Health and Well-Being Network Initiative. People interested in learning more about the Network should go to http://projects.iq.harvard.edu/wfhn/home. We thank the reviewers and other editors for their helpful comments.

Appendix A

Context Interview Guide—Scheduler

- How long have you been in this position?

- Did you work another job in [facility] before becoming the scheduler?

- What is the biggest issue around schedules or work hours in [facility]?

- aHow much variation is there between units on schedule-related issues? can you give me an example?

- Think of the toughest scheduling problem you've ever faced on this job, whether you were able to solve it or not. can you tell me about that? What strategies did you use to try and solve it? (Probe: using floaters, per diems)

- First, let's talk about the overall or weekly schedule. In general, what is the process for setting the schedule in [facility]?

- Who else do you work with to set the schedule? What role do they play?

- How much variation is there week-to-week?

- Are there certain times of the year that are the most challenging for scheduling?

- How do you manage these times?

- What if an employee needs a day off in advance? how far in advance do they need to put in a request?

- Who approves the request?

- Do you find coverage for them or is the employee responsible for that? (Probe: If scheduler finding coverage: What are the typical steps you go through to find coverage?)

- Can you think of a time when a request was denied? Why was it denied? Is that typical?

- Is the process the same for vacation requests, in terms of how far in advance the request needs to be turned in and approval? (If no, ask how it is different)

- What is the policy at [facility] regarding the amount of vacation that can be taken at one time?

- Are exceptions ever made for this? can you give me an example?

- We've talked about planned absences; now let's talk about call outs. How are last-minute requests for time off handled in [facility]?

- Does it matter if the reason is that the employee is ill as compared to other reasons, such as a sick child or other personal matter?

- To what extent does this differ in each unit? In what ways (if any)?

- How do you go about finding coverage for call outs? Who do you go to first, then second, etc.?

- Are there times when employees are responsible for finding their own coverage?

- At what point is disciplinary action taken against someone for calling out too frequently? What action is taken?

- Who is responsible for carrying out the disciplinary action?

- Is this corporate policy or specific to [facility]?

- Can you think of a time when an exception to this policy was made?

- To what degree are the policies regarding time off evenly enforced through [facility]?

- Are exceptions made for certain jobs or people? (ask for example or story)

Can you tell me about a time when you faced a conflict between labor costs, in other words staffing issues, and an employee's schedule preference? how did you manage that?

- What is the official policy on overtime at [facility]? Is this from corporate or from just [facility]?

- Can you tell me about a time when you had to violate this policy? Did you get in trouble because of it?

- How would an employee go about getting more hours on the schedule? What about reducing or cutting hours?

- Again, does this approach differ at all between units in this facility? How?

What things would you like to change about how scheduling is handled?

- We heard that a few [company] facilities have experimented with self-scheduling. have you tried self-scheduling or other innovative staffing or scheduling practices?

- If yes: What did you try? When?

- What did you like about that approach?

- What did not work so well?

- If no: Why do you think it has not been tried at [facility]?

- Do you think self-scheduling would be successful at [facility]? Whyor why not?

Is there anything out of the ordinary that you yourself have tried out? Something you're particularly proud of?

Appendix B

Table B.1. Scheduler Job-Crafting Breakdown.

| Schedulera | Type of scheduler | Job-crafting strategy | Rule-bound interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Cognitive | Physical | Relational | |||

| Althea | Balancer | Balanced | High | High | Medium |

| Elise | Balancer | Balanced | High | High | Medium |

| Harriet | Balancer | Balanced | High | High | Low |

| Audrey | Balancer | Balanced | Low | Medium | Medium |

| Klara | Balancer | Balanced | High | High | Low |

| Dana | Balancer | Balanced | Low | Medium | Medium |

| Gwen | Balancer | Balanced | High | Medium | Medium |

| Julianne | Balancer | Balanced | High | High | Low |

| Elenore | Enforcer | Employer | Low | Low | High |

| Gianna | Enforcer | Employer | Low | High | Medium |

| Aleah | Enforcer | Employer | Low | Low | High |

| Donna | Enforcer | Employer | High | Low | High |

| Lynette | Enforcer | Employer | Low | Low | High |

| Anju | Enforcer | Employer | Low | Low | High |

| Kayla | Enforcer | Employer | Low | Medium | High |

| Lorena | Enforcer | Employer | Low | Low | High |

| Maxine | Enforcer | Employer | Low | Low | High |

| Brisana | Employee-focused | Employee | Low | High | Low |

| Corina | Employee-focused | Employee | Low | High | Low |

| Faye | Patient-focused | Patient | Low | Medium | Medium |

| Helena | Patient-focused | Patient | Low | High | Low |

| Neva | Patient-focused | Patient | High | High | Low |

| Larissa | Patient-focused | Patient | Low | Medium | Medium |

| Tania | Patient-focused | Patient | Low | High | Low |

| Elena | Patient-focused | Patient | High | Medium | Medium |

| Petra | Patient-focused | Patient | Low | High | Medium |

Pseudonyms.

Footnotes

Although collective bargaining is mentioned in the generic job description, most Leef sites (including all 26 in our sample) are nonunion.

Brady explained how HPPD fluctuates: “If there are 100 residents in the facility on a given day and the direct care nursing staff works for a total of 350 hours over a 24 hour period, then the labor hours divided by the number of residents, results in 3.5 HPPD. If the census of residents goes up to 110 then the HPPD goes down for the same number of staff work hours” (2013a).

Portions of the results were presented at the national Academy of Management meetings in Boston in 2012, the Wharton People and Organizations conference in 2013, the 2014 Work and employment Relations in Health Care conference at Rutgers University, and the 2015 International Work Family conference at IESE business school at University of Navarra, Barcelona, Spain.

Contributor Information

Ellen Ernst Kossek, Management and Research Director of the Susan Bulkeley Butler Center for Leadership Excellence at Purdue University Krannert School Of Management.

Matthew M. Piszczek, Human Resource Management at University of Wisconsin Oshkosh.

Kristie L. Mcalpine, School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University.

Leslie B. Hammer, Oregon Healthy Workforce Center And Senior Scientist, Oregon Institute of Occupational Health Sciences at Oregon Health & Science University and Professor of Psychology at Portland State University.

Lisa Burke, worked on this while she was a Research Associate at the susan bulkeley butler center at Purdue university.

References

- Aiken Linda h, Llarke Sean P, Sloane Douglas M, Sochalski Julie, Silber Jeffirey H. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(16):1987–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertsen Karen, Garde Anne Helene, Nabe-Nielsen Kirsten, Hansen Ase Marie, Lund Henrik, Hvid Helge. Work-life balance among shift workers: Results from an intervention study about self-rostering. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2014;87(3):265–74. doi: 10.1007/s00420-013-0857-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard Jonathan F, Purnomo Hadi W. Short-term nurse scheduling in response to daily fluctuations in supply and demand. Health Care Management Science. 2005;8:315–24. doi: 10.1007/s10729-005-4141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barger Laura K, Cade Brian E, Ayas Najib T, Cronin John W, Rosner Bernard, Speizer Frank E, Czeishler Charles A. Extended work shifts and the risk of motor vehicle crashes among interns. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352(2):125–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg Justin M, Wrzesniewski Amy, Dutton Jane E. Perceiving and responding to challenges in job crafting at different ranks: When proactivity requires adaptivity. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2010;31(2-3):158–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bowblis John R, Lucas Judith A. The impact of state regulations on nursing home care practices. Journal of Regulatory Economics. 2012;42(1):52–72. [Google Scholar]

- Brady Eric. Clinical staffing in the nursing home. Nursing home families; 2013a. Accessed at http://www.nursinghomefamilies.com/NH_web/nurse_staffing.html (February 2, 2016) [Google Scholar]

- Brady Eric. How certified nursing homes are supposed to operate. Nursing home families; 2013b. Accessed at http://www.nursinghomefamilies.com/NH_web/how_NH_Operate.html (February 2, 2016) [Google Scholar]

- Braverman Harry. Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. New York: Monthly Review Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Brimmer Kelsey. Cut labor costs with smarter scheduling: Hospitals target workforce strategies to decrease operational costs. healthcare finance; 2013. Accessed at http://www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/research-ties-staffing-sustainablity (September 2014) [Google Scholar]