Abstract

Background and objectives

It is not known what proportion of United States patients with advanced CKD go on to receive RRT. In other developed countries, receipt of RRT is highly age dependent and the exception rather than the rule at older ages.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We conducted a retrospective study of a national cohort of 28,568 adults who were receiving care within the US Department of Veteran Affairs and had a sustained eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 between January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2009. We used linked administrative data from the US Renal Data System, US Department of Veteran Affairs, and Medicare to identify cohort members who received RRT during follow-up through October 1, 2011 (n=19,165). For a random 25% sample of the remaining 9403 patients, we performed an in-depth review of their VA–wide electronic medical records to determine the treatment status of their CKD.

Results

Two thirds (67.1%) of cohort members received RRT on the basis of administrative data. On the basis of the results of chart review, we estimate that an additional 7.5% (95% confidence interval, 7.2% to 7.8%) of cohort members had, in fact, received dialysis, that 10.9% (95% confidence interval, 10.6% to 11.3%) were preparing for and/or discussing dialysis but had not started dialysis at most recent follow-up, and that a decision had been made not to pursue dialysis in 14.5% (95% confidence interval, 14.1% to 14.9%). The percentage of cohort members who received or were preparing to receive RRT ranged from 96.2% (95% confidence interval, 94.4% to 97.4%) for those <45 years old to 53.3% (95% confidence interval, 50.7% to 55.9%) for those aged ≥85 years old. Results were similar after stratification by tertile of Gagne comorbidity score.

Conclusions

In this large United States cohort of patients with advanced CKD, the majority received or were preparing to receive RRT. This was true even among the oldest patients with the highest burden of comorbidity.

Keywords: clinical epidemiology; dialysis; end-stage renal disease; Adult; Comorbidity; Developed Countries; Electronic Health Records; Follow-Up Studies; glomerular filtration rate; Humans; kidney; Medicare; renal dialysis; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; Renal Replacement Therapy; Retrospective Studies; United States; Veterans

Introduction

The US Medicare Program spends >$30 billion annually to provide RRT, including maintenance dialysis and kidney transplant, to >400,000 Americans with advanced CKD (1). The annual incidence of RRT in the United States is several fold higher than that in many European nations (1,2). Whether the relatively higher incidence of RRT in the United States reflects a greater burden of kidney disease in the source population or differences in treatment practices for advanced CKD is not known.

Most of what is known about treatment practices for advanced CKD in the United States comes from the US Renal Data System (USRDS). However, similar to many other national registries of RRT, the USRDS does not collect information on patients who reach the advanced stages of CKD but do not receive RRT. There are several lines of indirect evidence to suggest that there may be a large potential reservoir of patients with advanced CKD in this country who are not treated with RRT, especially at older ages (>75 years old). Although the prevalence of CKD increases linearly with age, the incidence of RRT as reported by the USRDS plateaus and then, declines at older ages (1,3–6). Several studies conducted outside the United States suggest that it is relatively common for patients with advanced CKD not to receive RRT, especially at older ages (7,8). However, there is marked international variation in use of RRT (1,2,6), making it uncertain whether the results of these studies are generalizable to the United States.

The Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) is the largest integrated health care system in the United States. We conducted a retrospective study of a national cohort of patients receiving care within the VA to determine how often patients with advanced CKD do not receive RRT, the characteristics of these patients, and the clinical context in which these decisions occur.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

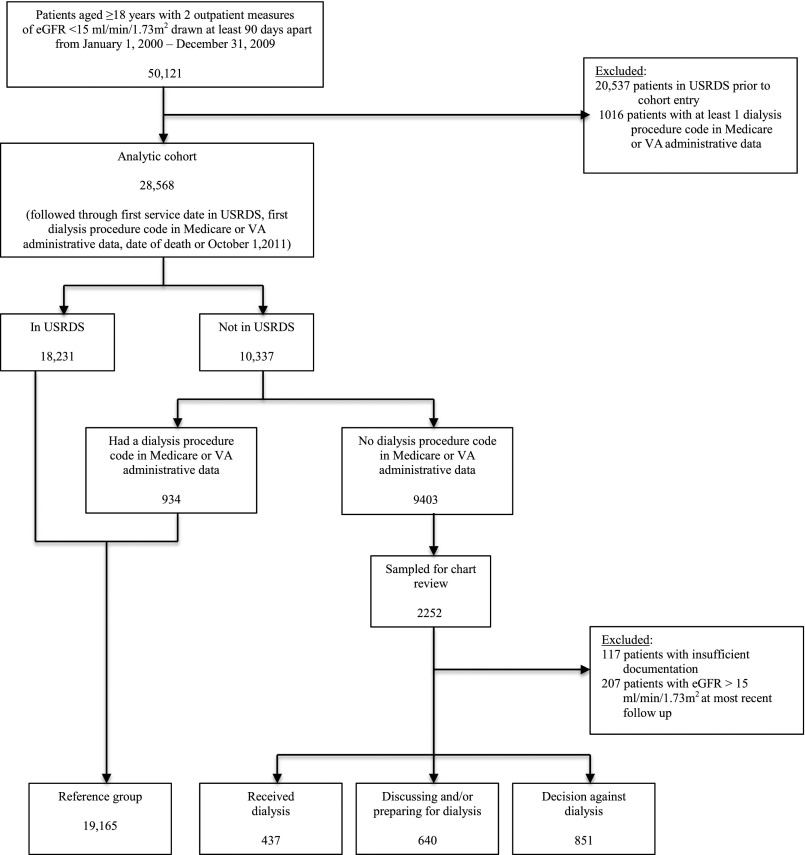

Using the VA data sources, we identified all veterans aged ≥18 years old with advanced CKD, which was defined as having an eGFR<15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 on at least two outpatient tests drawn at least 90 days apart between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2009 (n=50,121) (9). Date of cohort entry was defined as the date of the second eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2. We excluded patients who received RRT before cohort entry on the basis of registration in the USRDS (n=20,537) and procedure code search for dialysis in Medicare claims, VA inpatient and outpatient treatment, and Fee Basis files (which capture care received at non-VA facilities that is paid for by the VA) on or before the date of cohort entry (n=1016). This yielded an analytic cohort of 28,568 patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cohort derivation. USRDS, US Renal Data System; VA, Department of Veteran Affairs.

The Institutional Review Boards at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System and the University of Washington approved this study and waived the requirement to obtain informed consent from patients.

Patient Characteristics

We used the VA Vital Status File to ascertain patient age at cohort entry (categorized as <45 years old and then, in 5-year increments up to 85 years old), race (categorized as white, black, and other), and sex. We used the VA Decision Support System Laboratory Results File to ascertain serum creatinine measures, and eGFR was estimated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula. We used Medicare and VA administrative data to obtain information on outpatient nephrology clinic visits in the year before cohort entry and identify the following comorbid conditions present at cohort entry on the basis of International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision diagnostic codes on at least two claims during the year before cohort entry: coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis, peripheral artery disease, hypertension, diabetes, dementia, cancer, and stroke. We also calculated a Gagne comorbidity score (10), which combines the conditions included in the Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidity indices, to ascertain a comprehensive measure summarizing the overall burden of comorbidity for each patient at the time of cohort entry on the basis of diagnostic codes in Medicare and VA administrative files during the preceding year. We then categorized patients as having a low (scores <4), moderate (scores =4–6) or high (scores >6) burden of comorbidity on the basis of tertile of Gagne comorbidity score.

Outcome Measures

We used the USRDS records and dialysis procedure code search of Medicare and VA administrative files to identify patients who were treated with RRT during follow-up. Patients were followed through the first service date in the USRDS, the date of first dialysis procedure code in administrative files if the patient did not appear in the USRDS, the date of death (obtained from the VA Vital Status File), or October 1, 2011, whichever came first. To understand the treatment status of cohort members who did not appear in the USRDS and did not have a dialysis procedure code in administrative files during follow-up (n=9403), we identified a random 25% sample (n=2252) stratified by calendar year of cohort entry and the VA service network for detailed medical record review (Figure 1).

Medical Record Review

The VA has a comprehensive national electronic medical record system that includes progress notes for all inpatient and outpatient encounters of patients receiving care at its facilities. All progress notes are available in Text Integration Utility (TIU) format through the VA Corporate Data Warehouse. Chart review was conducted using TIU notes in each patient’s VA–wide electronic medical record from the time of cohort entry through death or October 1, 2011. To facilitate and enhance the completeness of chart review, we used Lucene text–searching software (11) to locate progress notes containing information about treatment decisions for advanced CKD. We used inclusive search queries that returned all discharge summaries, nephrology inpatient and outpatient progress notes, and all progress notes containing catchall terms, such as dialysis, ESRD, and kidney disease.

We used a combined inductive and deductive approach to content analysis of the medical record (12). Inductive content analysis is an unstructured approach to the reading of texts that facilitates identification of themes and patterns inherent to a phenomenon that have not been previously described. In deductive content analysis, reading of texts is aimed at determining whether they have attributes that are consistent with predefined themes and patterns. To accomplish this, two investigators (S.P.Y.W., a senior nephrology fellow, and A.M.O, a nephrologist with >15 years of clinical experience) reviewed the progress notes of 200 randomly selected patients in the sample to develop a coding schema to categorize patients into distinct groups reflecting their treatment status with respect to RRT at the time of most recent follow-up. Then, one investigator (S.P.Y.W.) assigned the remaining 2052 patients selected for chart review to prespecified treatment groups. Among those selected for chart review (n=2252), we excluded 207 from our analyses, because their eGFRs at most recent follow-up in the medical record were >15 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and we excluded 117 with insufficient documentation to characterize the clinical course of their CKD (Figure 1).

Analytic Approach

We used proportions, means and SDs, and chi-squared and ANOVA tests to compare the referent category of patients who were enrolled in the USRDS or had a dialysis procedure code in administrative data with patients in each of the clinically distinct subgroups identified in the chart review sample.

The results of chart review were then used to estimate the proportion and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of the overall cohort expected to belong to each treatment group. We evaluated the estimated distribution of treatment groups within each age group using a multinomial logistic regression model adjusted for all baseline patient characteristics and calendar year of cohort entry. We repeated the primary analysis after stratification by tertile of comorbidity score. To evaluate for temporal differences in treatment practices, we calculated the incidence of enrollment in the USRDS or having a dialysis procedure code in administrative data during follow-up for each age group stratifying by time period of cohort entry (2000–2004 versus 2005–2009).

Construction of the analytic dataset and statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and SPSS, version 19 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Outcomes

Of the 28,568 members of this cohort, 18,231 patients (63.8%) were registered in the USRDS, and an additional 934 patients (3.3%) had at least one dialysis treatment on the basis of dialysis procedure code search of Medicare and VA administrative files during follow-up (Figure 1). Median time to date of the USRDS enrollment or first dialysis procedure code in administrative files was 0.6 years (interquartile range, 0.2–1.2 years).

For the 1928 patients included in the in–depth chart review, median follow-up was 0.4 years (interquartile range, 0.1–1.3 years). These patients were grouped as follows (Figure 1): (1) received dialysis (n=437; 22.7%): patients with documentation in progress notes that they had received at least one dialysis treatment, despite not being registered in the USRDS or having a dialysis procedure code in administrative files; (2) discussing and/or preparing for dialysis (n=640; 33.2%): patients who had not started dialysis by the end of follow-up but were preparing for dialysis or engaged in ongoing discussions with providers about whether to undergo dialysis; and (3) decision against dialysis (n=851; 44.1%): patients for whom an explicit or implicit decision not to pursue dialysis had been made by the patients themselves, family members, and/or providers. Representative quotations from the medical record used to assign patients to each of these categories are presented in Table 1. For the 1749 sampled patients (90.7%) who died during follow-up, assigned categories reflect their treatment status at the time of death.

Table 1.

Description of treatment subgroups within a sample of patients with advanced CKD (n=1928) identified through in-depth review of patients’ medical record

| Clinical Course | Representative Quotes Abstracted from Patients’ Medical Records |

|---|---|

| Received dialysis: patients who were described in provider notes as having received at least one dialysis treatment but were not registered in the US Renal Data System and did not have a dialysis procedure in Medicare or Department of Veteran Affairs administrative data | “[P]atient had initiated on one course of hemodialysis … He then expressed his wishes that he did not want to utilize technology in the form of hemodialysis to maintain his life in its current status … he has chosen to pursue hospice” |

| “Patient was dialyzed 3 times starting on September 10 … Patient was found pulseless and apneic in the morning of September 13” | |

| “Patient did have [a] history of renal failure requiring hemodialysis twice several months ago at an outside hospital. Patient [is] unsure of [the] details” | |

| Discussing and/or preparing for dialysis: patients and/or their family members were discussing or preparing for the possibility of dialysis but had not yet started dialysis by the end of follow-up | “[H]e verbalized moderate anxiety about making decision about dialysis. He does not know if he wants dialysis” |

| “[A]s the long-term plan, patient prefers peritoneal dialysis” | |

| “All three options (hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and renal transplant) were discussed with the patient in detail … Patient needs more time to think about it” | |

| “[H]e has a fistula in left arm just in case he has to go on to dialysis” | |

| Decision against dialysis: patients and/or their family members and providers made an explicit or implicit decision to not pursue dialysis | “Again discussed dialysis with patient's brother and power of attorney who declined dialysis” |

| “[H]as been seen by nephrology multiple times in the past and has repeatedly refused consideration for dialysis” | |

| “[N]ot a candidate for dialysis—demented, end stage acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), not on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), dialysis wouldn’t prolong life” | |

| “[M]an with multiple medical problems including disseminated T cell lymphoma, congestive heart failure, renal failure … now receiving palliative care … not a dialysis candidate as patient [is] hospice” |

Patient Characteristics

Compared with the referent group of patients who were registered in the USRDS or had a dialysis procedure code in administrative files, patients who had, in fact, received some dialysis on the basis of chart review, those who were preparing and/or discussing dialysis, and those in whom a decision against dialysis had been made were older, were more often white, had a higher burden of comorbidity, and had less nephrology care in the year before cohort entry (Table 2). These differences persisted in adjusted analyses (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients in each treatment group for advanced CKD (n=28,568)

| Characteristics at Cohort Entry | Enrolled in the USRDS or Had a Dialysis Procedure Code,a n=19,165 | Chart Review,b n=1928 | P Valuec | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received Dialysis, n=437 | Discussing and/or Preparing for Dialysis, n=640 | Decision against Dialysis, n=851 | |||

| Mean age (SD), yr | 65.4 (11.1) | 68.3 (10.5) | 68.4 (10.8) | 75.0 (10.3) | <0.001 |

| Race | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 11,133 (58.1) | 241 (55.1) | 363 (56.7) | 567 (66.6) | |

| Black | 6307 (32.9) | 108 (24.7) | 140 (21.9) | 165 (19.4) | |

| Other | 1725 (9.0) | 8 (20.1) | 137 (21.4) | 119 (14.0) | |

| Sex | 0.40 | ||||

| Women | 302 (1.6) | 4 (0.9) | 8 (1.3) | 9 (1.1) | |

| Men | 1863 (98.4) | 433 (99.1) | 632 (98.8) | 842 (98.9) | |

| Mean Gagne comorbidity score (SD) | 4.3 (2.4) | 5.9 (2.7) | 5.1 (2.8) | 6.1 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | 5440 (28.4) | 199 (45.5) | 219 (34.2) | 354 (41.6) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 7062 (36.8) | 211 (48.3) | 280 (43.8) | 386 (45.4) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 5440 (28.4) | 199 (45.5) | 219 (34.2) | 354 (41.6) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11,950 (62.4) | 254 (58.1) | 340 (53.1) | 446 (52.4) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 2439 (12.7) | 75 (17.2) | 96 (15.0) | 142 (16.7) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 3114 (16.2) | 109 (24.9) | 169 (26.4) | 273 (32.1) | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2749 (14.3) | 126 (28.8) | 151 (23.6) | 241 (28.3) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 239 (1.2) | 17 (3.9) | 19 (3.0) | 75 (8.8) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 1458 (7.6) | 31 (7.1) | 63 (9.8) | 109 (12.8) | <0.001 |

| Cirrhosis | 202 (1.1) | 19 (4.3) | 16 (2.5) | 17 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| Mean nephrology clinic visits in year prior (SD) | 4.4 (4.1) | 3.8 (3.2) | 3.8 (3.4) | 3.5 (4.8) | <0.001 |

Values presented as n (%) except for where indicated. USRDS, US Renal Data System.

In Medicare or Department of Veteran Affairs administrative files.

Of a random sample of patients who were not enrolled in the USRDS during follow-up and did not have a dialysis procedure code during follow-up.

Corresponds to chi-squared or ANOVA tests where appropriate.

Table 3.

Characteristics associated with each treatment group for advanced kidney disease (n=28,568)

| Characteristics at Cohort Entry | aORa (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Received Dialysis by Chart Review | Discussing or Preparing for Dialysis | Decision against Dialysis | |

| Age, yr | |||

| <65 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 65–74 | 1.65 (1.29 to 2.11) | 1.32 (1.07 to 1.63) | 2.08 (1.65 to 2.63) |

| ≥75 | 1.44 (1.11 to 1.86) | 1.46 (1.19 to 1.80) | 5.83 (4.74 to 7.17) |

| Race | |||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Black | 0.98 (0.77 to 1.24) | 0.81 (0.66 to 0.99) | 0.70 (0.58 to 0.84) |

| Other | 2.87 (2.20 to 3.76) | 2.98 (2.40 to 3.70) | 2.17 (1.74 to 2.72) |

| Sex, men (versus women) | 1.47 (0.54 to 4.01) | 1.14 (0.56 to 2.35) | 1.00 (0.50 to 2.02) |

| Burden of comorbidity | |||

| Low | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Moderate | 1.99 (1.51 to 2.64) | 1.35 (1.10 to 1.66) | 1.54 (1.26 to 1.89) |

| High | 3.38 (2.43 to 4.71) | 1.64 (1.25 to 2.15) | 3.07 (2.42 to 3.90) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 0.84 (0.56 to 1.26) | 0.75 (0.54 to 1.04) | 0.54 (0.42 to 0.70) |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.13 (0.90 to 1.40) | 1.15 (0.96 to 1.38) | 0.86 (0.73 to 1.01) |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.19 (0.94 to 1.52) | 0.98 (0.80 to 1.21) | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.23) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.68 (0.55 to 0.84) | 0.64 (0.54 to 0.76) | 0.78 (0.67 to 0.91) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 1.01 (0.77 to 1.32) | 1.01 (0.80 to 1.28) | 0.94 (0.77 to 1.15) |

| Cancer | 1.28 (1.01 to 1.630 | 1.50 (1.23 to 1.82) | 1.40 (1.19 to 1.65) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.47 (1.17 to 1.86) | 1.42 (1.16 to 1.75) | 1.33 (1.11 to 1.58) |

| Dementia | 1.99 (1.18 to 3.36) | 1.68 (1.03 to 2.76) | 3.41 (2.53 to 4.60) |

| Stroke | 0.71 (0.48 to 1.03) | 1.16 (0.88 to 1.52) | 1.40 (1.11 to 1.75) |

| Cirrhosis | 2.98 (1.78 to 4.97) | 1.84 (1.07 to 3.15) | 1.91 (1.11 to 3.29) |

| ≥4 (versus <4) Nephrology clinic visits in year prior | 0.40 (0.32 to 0.50) | 0.54 (0.45 to 0.65) | 0.32 (0.26 to 1.09) |

Multinomial logistic regression model adjusted for age, race, sex, comorbidity burden, comorbidities, prior nephrology care, and year of cohort entry. aOR, adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Reference group includes patients who were enrolled in the US Renal Data System or had a dialysis procedure code in Medicare or Department of Veteran Affairs administrative files.

Age-Stratified Analyses

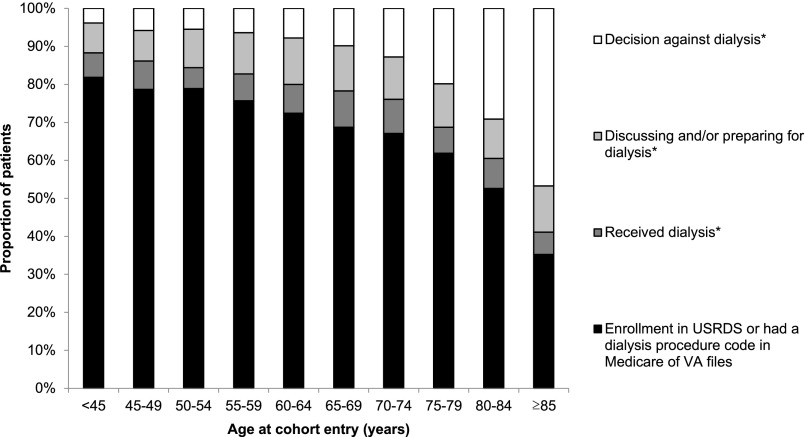

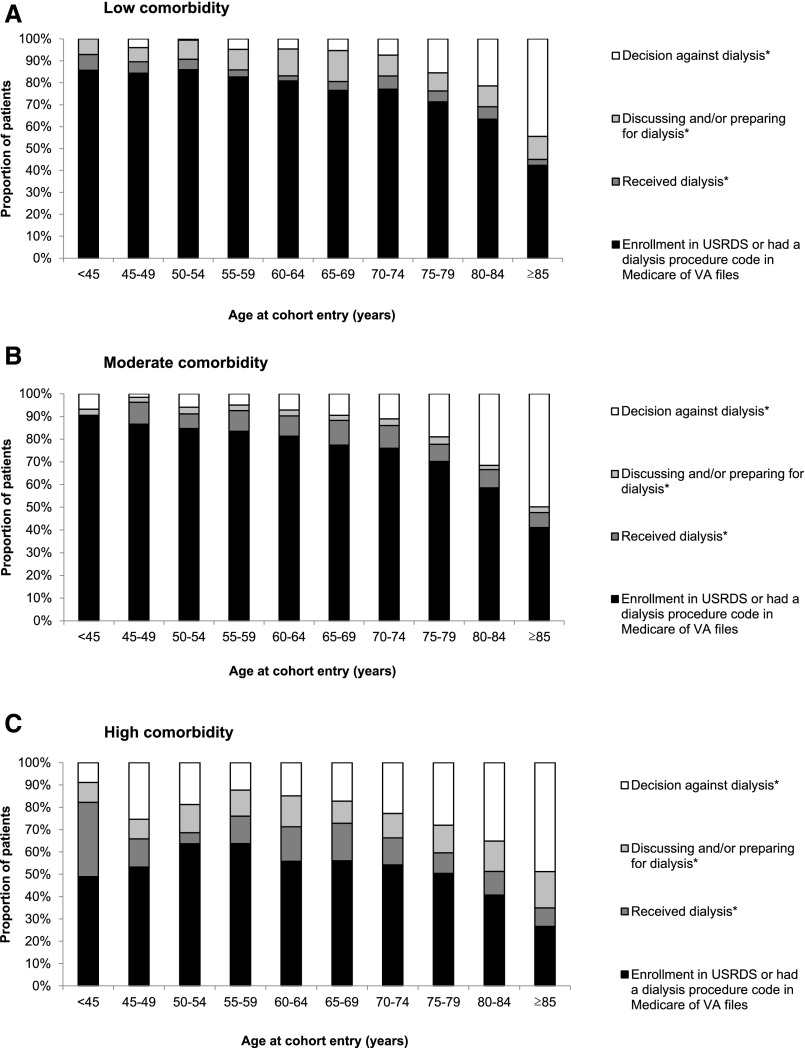

On the basis of chart review for this random sample of patients, we estimate that the proportion of all cohort members who received RRT on the basis of the USRDS enrollment, dialysis procedure code search, and chart review or were preparing for or discussing dialysis decreased linearly with age from 96.2% (95% CI, 94.4% to 97.4%) among patients aged <45 years old to 53.3% (95% CI, 50.7% to 55.9%) among patients aged ≥85 years old (adjusted trend; P value <0.001) (Figure 2). Conversely, the decision not to pursue dialysis was more common at older ages, increasing from an estimated 3.8% (95% CI, 2.6% to 5.6%) among patients aged <45 years old to 46.7% (95% CI, 44.1% to 49.3%) among patients aged ≥85 years old (adjusted trend; P value <0.001). Analyses stratified by tertile of comorbidity score were broadly consistent with the primary analysis (Figure 3). For example, for patients aged ≥85 years old, the estimated proportion of patients in whom a decision against dialysis had been made was similar for those in the lowest (44.5%; 95% CI, 39.5% to 49.6%) versus highest (48.8%; 95% CI, 44.4% to 53.3%) tertile of comorbidity (unadjusted P=0.60). The incidence of RRT on the basis of enrollment in the USRDS or dialysis procedure code search of administrative files for cohort members in each age group was similar for those who entered the cohort earlier (2000–2004) versus later (2005–2009) in time (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Age differences in treatment decisions and practices for advanced kidney disease. *On the basis of chart review of a random sample of patients who were not enrolled in the US Renal Data System (USRDS) and did not have a dialysis procedure code in Medicare or Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) administrative files during follow-up.

Figure 3.

Age differences in treatment decisions and practices for advanced kidney disease stratified by comorbidity score. (A) Low comorbidity. (B) Moderate comorbidity. (C) High comorbidity. *On the basis of chart review of a random sample of patients who were not enrolled in the US Renal Data System (USRDS) and did not have a dialysis procedure code in Medicare or Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) administrative files during follow-up.

Discussion

Among a national cohort of patients with advanced CKD receiving care in the VA, most patients were enrolled in the USRDS (63.8%) or had a dialysis procedure code in VA or Medicare administrative files (3.3%) during follow-up. On the basis of in–depth chart review for a random sample of the remaining patients, we estimate that an additional 7.5% of cohort members had, in fact, received at least one dialysis treatment not captured in the USRDS or administrative data and that 10.9% were discussing and/or preparing for dialysis but had not yet started dialysis at end of follow-up. Thus, at most recent follow-up, the overwhelming majority (85.5%) of patients had either received—or were preparing to receive—RRT. In only 14.5% of cohort members was there an implicit or explicit decision not to pursue dialysis.

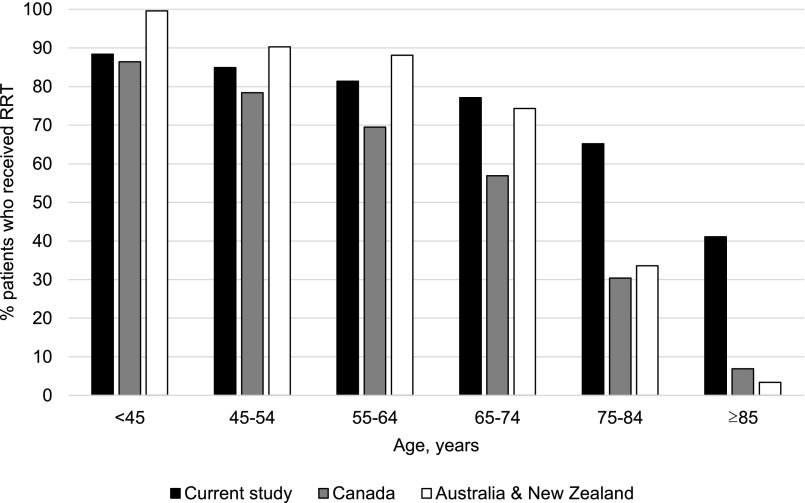

The proportion of patients in this cohort who were treated with RRT is higher than that previously reported for other developed nations (7,8). In a large retrospective study conducted in Canada using registry and administrative records from 2002 to 2008, Hemmelgarn et al. (7) found that 51.4% of patients who developed kidney failure (defined as a sustained eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or receipt of dialysis or kidney transplant) were treated with RRT. In a retrospective study using registry and death certificate data from New Zealand and Australia between 2003 and 2007, Sparke et al. (8) reported that 51.2% of patients with kidney failure (defined as either enrollment in the RRT registry or death from kidney disease without receipt of dialysis or kidney transplant) received RRT. However, source data for these studies lacked information on the clinical circumstances of those patients who did not receive RRT, such as whether there had been a decision not to offer or receive RRT.

Differences in the use of RRT between our study compared with that in these earlier studies are much more striking for older than for younger age groups (Figure 4). The percentage of patients aged <45 years old treated with RRT in our cohort (88.4%) was similar to those reported in the works by Hemmelgarn et al. (7) (86.3%) and Sparke et al. (8) (>95.0%). However, at older ages, the proportion treated with RRT was far higher for members of our cohort; 41.1% of patients aged ≥85 years old in our cohort were treated with RRT as compared with 6.8% and <5.0% among similarly aged patients described by Hemmelgarn et al. (7) and Sparke et al. (8), respectively. Furthermore, although burden of comorbidity is a key determinant of prognosis in patients who initiate dialysis (5,13–15), this seemed to have little effect on decisions about RRT. Even among members of the oldest age group with the highest burden of comorbidity, most received or were preparing to receive RRT at last follow-up. This finding is consistent with the observation that the incidence rate of RRT in the United States greatly surpasses that reported for European populations with a similar prevalence of advanced CKD and other significant chronic illness (4). In this study, patients with a higher versus lower burden of comorbidity were less likely to have initiated RRT but also, more likely to still be preparing for RRT at most recent follow-up, which might suggest that dialysis had been recommended for these patients for whom the competing risk of death may have exceeded their risk of developing a need to initiate RRT. In a survey study of United States nephrologists, a minority reported that they would offer more conservative therapy, such as palliative care, as an alternative to RRT to older patients with multimorbidity (16). Taken in this context, our findings reiterate concerns that, in the United States, decisions about RRT may not be strongly guided by the individual considerations and preferences of patients and instead, reflect wider health system and physician practices favoring more liberal use of interventions intended to lengthen life (17–22).

Figure 4.

International differences in use of RRT among patients with advanced CKD. Hemmelgarn et al. and Sparke et al. include the original data for Canada and Australia/New Zealand, respectively (7,8).

There were other notable differences in RRT practices across patient subgroups. Use of RRT was more common and decisions against dialysis were less common among black as compared with white patients. This finding is in agreement with prior studies reporting greater use of other potentially life–sustaining treatments, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation and mechanical ventilation, and less frequent use of hospice among black as compared with white patients with advanced CKD (17,18,23). Use of RRT was also less common and decisions against dialysis were more common among patients with higher comorbidity scores and histories of dementia, stroke, cancer, and cirrhosis. This finding seems consistent with other studies, in which nephrologists reported viewing dialysis as undesirable and palliative care referral as more appropriate in circumstances of severe cognitive and/or functional impairment or terminal illness from another condition (24–27).

This study has several limitations. First, the study population was limited to veterans who underwent serum creatinine measurement at a VA facility, and thus, it begs the question of whether study findings are generalizable to those receiving care in other health systems or other United States populations with advanced CKD, especially women. Given prior work that suggests that dialysis initiation practices are more conservative within versus outside the VA (19), we suspect that the proportion of patients treated with RRT in this study is probably lower than would be expected for members of the general United States population with advanced CKD. Second, differences in study design argue for caution in comparing rates of RRT in our study with those reported in prior studies conducted outside the United States (7,8). The proportion of patients treated with RRT is likely sensitive to exclusion and inclusion criteria, such as the threshold level of eGFR and requirement for chronicity. We chose to focus our study on patients with a sustained eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 to examine treatment decisions and practices among those patients most likely to receive RRT. Treatment rates would almost certainly have been lower if we had selected a higher eGFR threshold and included patients with transient loss of eGFR. Third, although we adopted a rigorous approach to capture episodes of dialysis occurring within the VA, at non-VA facilities but that were paid for by the VA, and under fee for service Medicare, we were not able to capture dialysis treatments paid for by Medicare Advantage or private insurance. Thus, if anything, our results likely underestimate the proportion of cohort members who received dialysis. Fourth, categorization of patients into treatment groups was on the basis of documentation in the VA electronic medical record, which might not fully or precisely capture the clinical context or attitudes toward dialysis held by individual patients. Categorization was also on the basis of decisions documented at most recent follow-up and does not capture changes in patients’ preferences for dialysis during the course of their illness. Our study findings also cannot address the adequacy of patients’ understanding of their treatment options and engagement in decision making about RRT.

In this large national cohort of patients with advanced CKD in the VA system, dialysis initiation practices among older patients were far more liberal than those reported for other developed countries (7,8). Our findings underscore the relevance of shared decision making for dialysis (28) to ensure that treatment decisions uphold the priorities and preferences of individual patients and are grounded in realistic expectations about prognosis and the expected benefits and harms of this treatment.

Disclosures

This work was supported by Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Services Research and Development grants IIR 09-094 (principal investigator P.L.H.) and IIR 12-126 (principal investigator A.M.O.) and Interagency Agreement between the VA Puget Sound and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention IAA 15FED1505101-0001 (principal investigator A.M.O.). S.P.Y.W. is supported by the Clinical Scientist in Nephrology Fellowship from the American Kidney Fund. C.-F.L. receives research funding from the VA Health Services Research and Development Service. A.M.O. receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the VA Health Services Research and Development Service. A.M.O. also receives an honorarium from the American Society of Nephrology and royalties from UpToDate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pamela Green, Margaret Yu, and Christine Sulc for their assistance with data programming, data analysis, and study coordination, respectively, for this study.

The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. S.P.Y.W. and A.M.O. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the VA.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Practice Change Is Needed for Dialysis Decision Making with Older Adults with Advanced Kidney Disease,” on pages 1732–1734.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.03760416/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System : 2015 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 2.ERA-EDTA : ERA-EDTA Registry Annual Report 2013, Academic Medical Center, Department of Medical Informatics, Amsterdam, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 298: 2038–2047, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallan SI, Coresh J, Astor BC, Asberg A, Powe NR, Romundstad S, Hallan HA, Lydersen S, Holmen J: International comparison of the relationship of chronic kidney disease prevalence and ESRD risk. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2275–2284, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurella M, Covinsky KE, Collins AJ, Chertow GM: Octogenarians and nonagenarians starting dialysis in the United States. Ann Intern Med 146: 177–183, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Treit K, Lam D, O’Hare AM: Timing of dialysis initiation in the geriatric population: Toward a patient-centered approach. Semin Dial 26: 682–689, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hemmelgarn BR, James MT, Manns BJ, O’Hare AM, Muntner P, Ravani P, Quinn RR, Turin TC, Tan Z, Tonelli M; Alberta Kidney Disease Network : Rates of treated and untreated kidney failure in older vs younger adults. JAMA 307: 2507–2515, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sparke C, Moon L, Green F, Mathew T, Cass A, Chadban S, Chapman J, Hoy W, McDonald S: Estimating the total incidence of kidney failure in Australia including individuals who are not treated by dialysis or transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis 61: 413–419, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Kidney Foundation : K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 39[Suppl 1]: S1–S266, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gagne JJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Levin R, Schneeweiss S: A combined comorbidity score predicted mortality in elderly patients better than existing scores. J Clin Epidemiol 64: 749–759, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammond KW, Laundry R, O’Leary TM, Jones WP: Use of text search to effectively identify lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among veterans. Presented at the System Sciences (HICSS) 2013 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krippendorff K: Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 3rd Ed., Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE: Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1955–1962, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandna SM, Schulz J, Lawrence C, Greenwood RN, Farrington K: Is there a rationale for rationing chronic dialysis? A hospital based cohort study of factors affecting survival and morbidity. BMJ 318: 217–223, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith C, Da Silva-Gane M, Chandna S, Warwicker P, Greenwood R, Farrington K: Choosing not to dialyse: Evaluation of planned non-dialytic management in a cohort of patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephron Clin Pract 95: c40–c46, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parvez S, Abdel-Kader K, Pankratz VS, Song MK, Unruh M: Provider knowledge, attitudes and practices surrounding conservative management for patients with advanced CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 812–820, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med 172: 661–663, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong SP, Kreuter W, Curtis JR, Hall YN, O’Hare AM: Trends in in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation and survival in adults receiving maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med 175: 1028–1035, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu MK, O’Hare AM, Batten A, Sulc CA, Neely EL, Liu CF, Hebert PL: Trends in timing of dialysis initiation within versus outside the Department of Veteran Affairs. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1418–1427, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong SP, Vig EK, Taylor JS, Burrows NR, Liu CF, Williams DE, Hebert PL, O’Hare AM: Timing of initiation of maintenance dialysis: A qualitative analysis of the electronic medical records of a national cohort of patients form the Department of Veteran Affairs. JAMA Intern Med 176: 228–235, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaufman SR: Ordinary Medicine: Extraordinary Treatments, Longer Lives and Where to Draw the Line, London, Duke University Press, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Hare AM, Rodriguez RA, Hailpern SM, Larson EB, Kurella Tamura M: Regional variation in health care intensity and treatment practices for end-stage renal disease in older adults. JAMA 304: 180–186, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas BA, Rodriguez RA, Boyko EJ, Robinson-Cohen C, Fitzpatrick AL, O’Hare AM: Geographic variation in black-white differences in end-of-life care for patients with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1171–1178, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sekkarie M, Cosma M, Mendelssohn D: Nonreferral and nonacceptance to dialysis by primary care physicians and nephrologists in Canada and the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 38: 36–41, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKenzie JK, Moss AH, Feest TG, Stocking CB, Siegler M: Dialysis decision making in Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 31: 12–18, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sekkarie MA, Moss AH: Withholding and withdrawing dialysis: The role of physician specialty and education and patient functional status. Am J Kidney Dis 31: 464–472, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halvorsen K, Slettebø A, Nortvedt P, Pedersen R, Kirkevold M, Nordhaug M, Brinchmann BS: Priority dilemmas in dialysis: The impact of old age. J Med Ethics 34: 585–589, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Renal Physicians Association : Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis, 2nd Ed., Rockville, MD, Renal Physicians Association, 2010 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.